Russia

Coordinates: 60°N 90°E / 60°N 90°E

Russian Federation

| |

|---|---|

Anthem: "Государственный гимн Российской Федерации" "Gosudarstvennyy gimn Rossiyskoy Federatsii" "State Anthem of the Russian Federation" | |

![Location of Russia with Crimea in light green[a]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5e/Russian_Federation_%28orthographic_projection%29_-_only_Crimea_disputed.svg/220px-Russian_Federation_%28orthographic_projection%29_-_only_Crimea_disputed.svg.png) | |

| Capital and largest city | Moscow 55°45′N 37°37′E / 55.750°N 37.617°E |

| Official language and national language | Russian[3] |

| Recognised national languages | See Languages of Russia |

| Ethnic groups (2010)[4] | |

| Religion (2017)[5] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Russian |

| Government | Federal dominant party semi-presidential constitutional republic |

| Vladimir Putin | |

| Mikhail Mishustin | |

| Valentina Matviyenko | |

| Vyacheslav Volodin | |

| Vyacheslav Lebedev | |

| Legislature | Federal Assembly |

| Federation Council | |

| State Duma | |

| Formation | |

| c. 862 | |

| 879 | |

| 1283 | |

| 16 January 1547 | |

| 2 November 1721 | |

| 15 March 1917 | |

| 12 December 1991 | |

| 12 December 1993 | |

| 18 March 2014 | |

| 4 July 2020 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 17,098,246 km2 (6,601,670 sq mi)[6] (without Crimea)[b] (1st) |

• Water (%) | 13[8] (including swamps) |

| Population | |

• 2021 [10] estimate | (9th) |

• Density | 8.4/km2 (21.8/sq mi) (225th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2018) | medium · 98th |

| HDI (2019) | very high · 52nd |

| Currency | Russian ruble (₽) (RUB) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 to +12 |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Mains electricity | 230 V–50 Hz |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +7 |

| ISO 3166 code | RU |

| Internet TLD | |

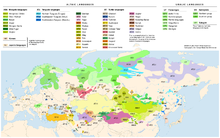

Russia,[c] or the Russian Federation,[d][14] is a transcontinental country located in Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east, and from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Black and Caspian seas in the south. Russia covers 17,125,191 square kilometres (6,612,073 sq mi), spanning more than one-eighth of the Earth's inhabited land area, stretching eleven time zones, and bordering 16 sovereign nations. Moscow is the country's capital and largest city; other major cities include Saint Petersburg, Novosibirsk, Yekaterinburg, Kazan, Nizhny Novgorod, Chelyabinsk and Samara.

Russia is the largest country in the world, the ninth-most populous country, as well as the most populous country in Europe. The country is one of the world's most sparsely populated and urbanized. About half of the country's total area is forested, concentrating around four-fifths of its total population of over 146.8 million on its smaller and dense western portion, as opposed to its larger and sparse eastern portion. Russia is administratively divided into 85 federal subjects. The Moscow Metropolitan Area is the largest metropolitan area in Europe, and among the largest in the world, with more than 20 million residents.

The East Slavs emerged as a recognisable group in Europe between the 3rd and 8th centuries AD. The medieval state of Rus' arose in the 9th century. In 988 it adopted Orthodox Christianity from the Byzantine Empire, beginning the synthesis of Byzantine and Slavic cultures that defined Russian culture for the next millennium. Rus' ultimately disintegrated into a number of smaller states, until it was finally reunified by the Grand Duchy of Moscow in the 15th century. By the 18th century, the nation had greatly expanded through conquest, annexation, and exploration to become the Russian Empire, which became a major European power, and the third-largest empire in history. Following the Russian Revolution, the Russian SFSR became the largest and leading constituent of the Soviet Union, the world's first constitutionally socialist state. The Soviet Union played a decisive role in the Allied victory in World War II, and emerged as a superpower and rival to the United States during the Cold War. The Soviet era saw some of the most significant technological achievements of the 20th century. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Russian SFSR reconstituted itself as the Russian Federation and is recognised as the continuing legal personality and a successor of the Soviet Union. Following the constitutional crisis of 1993, a new constitution was adopted, and Russia has since been governed as a federal semi-presidential republic.

Russia is described as a potential superpower, with the world's second-most powerful military, and the fourth-highest military expenditure. As a recognised nuclear-weapon state, the country possesses the world's largest stockpile of nuclear weapons. Its economy ranks as the eleventh-largest in the world by nominal GDP and the sixth-largest by PPP. Russia's extensive mineral and energy resources are the largest in the world, and it is one of the leading producers of oil and natural gas globally. It hosts the world's ninth-greatest number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and is simultaneously ranked very high in the Human Development Index, with a universal healthcare system, and a free university education. Russia is a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, a member of the SCO, the G20, the Council of Europe, the APEC, the OSCE, the IIB and the WTO, as well as the leading member of the CIS, the CSTO, and the EAEU.

Etymology

The name Russia is derived from Rus', a medieval state populated mostly by the East Slavs. However, this proper name became more prominent in the later history, and the country typically was called by its inhabitants "Русская Земля" (russkaja zemlja), which can be translated as "Russian Land" or "Land of Rus'". In order to distinguish this state from other states derived from it, it is denoted as Kievan Rus' by modern historiography. The name Rus itself comes from the early medieval Rus' people, and Swedish merchants and warriors,[15][16] who relocated from across the Baltic Sea and founded a state centered on Novgorod that later became Kievan Rus.

An old Latin version of the name Rus' was Ruthenia, mostly applied to the western and southern regions of Rus' that were adjacent to Catholic Europe. The current name of the country, Россия (Rossija), comes from the Byzantine Greek designation of the Rus', Ρωσσία Rossía—spelled Ρωσία (Rosía pronounced [roˈsia]) in Modern Greek.[17]

The standard way to refer to citizens of Russia is "Russians" in English,[18] and rossiyane (Russian: россияне) in Russian. There are two Russian words which are commonly translated into English as "Russians". One is "русские" (russkiye), which most often means "ethnic Russians". Another is "россияне" (rossiyane), which means "Russian citizens", regardless of ethnicity.[citation needed]

History

Early history

Nomadic pastoralism developed in the Pontic-Caspian steppe beginning in the Chalcolithic.[19]

In classical antiquity, the Pontic Steppe was known as Scythia. Beginning in the 8th century BC, Ancient Greek traders brought their civilization to the trade emporiums in Tanais and Phanagoria. Ancient Greek explorers, most notably Pytheas, even went as far as modern day Kaliningrad, on the Baltic Sea. Romans settled on the western part of the Caspian Sea, where their empire stretched towards the east.[dubious ][20] In the 3rd to 4th centuries AD a semi-legendary Gothic kingdom of Oium existed in Southern Russia until it was overrun by Huns. Between the 3rd and 6th centuries AD, the Bosporan Kingdom, a Hellenistic polity which succeeded the Greek colonies,[21] was also overwhelmed by nomadic invasions led by warlike tribes, such as the Huns and Eurasian Avars.[22] A Turkic people, the Khazars, ruled the lower Volga basin steppes between the Caspian and Black Seas until the 10th century.[23]

The ancestors of modern Russians are the Slavic tribes, whose original home is thought by some scholars to have been the wooded areas of the Pinsk Marshes.[24] The East Slavs gradually settled Western Russia in two waves: one moving from Kiev toward present-day Suzdal and Murom and another from Polotsk toward Novgorod and Rostov. From the 7th century onwards, the East Slavs constituted the bulk of the population in Western Russia[25] and assimilated the native Finno-Ugric peoples, including the Merya, the Muromians, and the Meshchera.

Kievan Rus'

The establishment of the first East Slavic states in the 9th century coincided with the arrival of Varangians, the traders, warriors and settlers from the Baltic Sea region. Primarily they were Vikings of Scandinavian origin, who ventured along the waterways extending from the eastern Baltic to the Black and Caspian Seas.[26] According to the Primary Chronicle, a Varangian from Rus' people, named Rurik, was elected ruler of Novgorod in 862. In 882, his successor Oleg ventured south and conquered Kiev,[27] which had been previously paying tribute to the Khazars. Oleg, Rurik's son Igor and Igor's son Sviatoslav subsequently subdued all local East Slavic tribes to Kievan rule, destroyed the Khazar khaganate and launched several military expeditions to Byzantium and Persia.

In the 10th to 11th centuries Kievan Rus' became one of the largest and most prosperous states in Europe.[28] The reigns of Vladimir the Great (980–1015) and his son Yaroslav the Wise (1019–1054) constitute the Golden Age of Kiev, which saw the acceptance of Orthodox Christianity from Byzantium and the creation of the first East Slavic written legal code, the Russkaya Pravda.

In the 11th and 12th centuries, constant incursions by nomadic Turkic tribes, such as the Kipchaks and the Pechenegs, caused a massive migration of Slavic populations to the safer, heavily forested regions of the north, particularly to the area known as Zalesye.[29]

The age of feudalism and decentralization was marked by constant in-fighting between members of the Rurik Dynasty that ruled Kievan Rus' collectively. Kiev's dominance waned, to the benefit of Vladimir-Suzdal in the north-east, Novgorod Republic in the north-west and Galicia-Volhynia in the south-west.

Ultimately Kievan Rus' disintegrated, with the final blow being the Mongol invasion of 1237–40[30] that resulted in the destruction of Kiev[31] and the death of about half the population of Rus'.[32] The invading Mongol elite, together with their conquered Turkic subjects (Cumans, Kipchaks, Bulgars), became known as Tatars, forming the state of the Golden Horde, which pillaged the Russian principalities; the Mongols ruled the Cuman-Kipchak confederation and Volga Bulgaria (modern-day southern and central expanses of Russia) for over two centuries.[33]

Galicia-Volhynia was eventually assimilated by the Kingdom of Poland, while the Mongol-dominated Vladimir-Suzdal and Novgorod Republic, two regions on the periphery of Kiev, established the basis for the modern Russian nation.[34] The Novgorod Republic together with Pskov retained some degree of autonomy during the time of the Mongol yoke and were largely spared the atrocities that affected the rest of the country. Led by Prince Alexander Nevsky, Novgorodians repelled the invading Swedes in the Battle of the Neva in 1240, as well as the Germanic crusaders in the Battle of the Ice in 1242, breaking their attempts to colonise the Northern Rus'.[citation needed]

Grand Duchy of Moscow

The most powerful state to eventually arise after the destruction of Kievan Rus' was the Grand Duchy of Moscow ("Muscovy" in the Western chronicles), initially a part of Vladimir-Suzdal. While still under the domain of the Mongol-Tatars and with their connivance, Moscow began to assert its influence in the Central Rus' in the early 14th century, gradually becoming the leading force in the process of the Rus' lands' reunification and expansion of Russia.[35] Moscow's last rival, the Novgorod Republic, prospered as the chief fur trade center and the easternmost port of the Hanseatic League.

Times remained difficult, with frequent Mongol-Tatar raids. Agriculture suffered from the beginning of the Little Ice Age. As in the rest of Europe, plague was a frequent occurrence between 1350 and 1490.[36] However, because of the lower population density and better hygiene—widespread practicing of banya, a wet steam bath—the death rate from plague was not as severe as in Western Europe,[37] and population numbers recovered by 1500.[36]

Led by Prince Dmitry Donskoy of Moscow and helped by the Russian Orthodox Church, the united army of Russian principalities inflicted a milestone defeat on the Mongol-Tatars in the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380. Moscow gradually absorbed the surrounding principalities, including formerly strong rivals such as Tver and Novgorod.

Ivan III ("the Great") finally threw off the control of the Golden Horde and consolidated the whole of Central and Northern Rus' under Moscow's dominion. He was also the first to take the title "Grand Duke of all the Russias".[38] After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Moscow claimed succession to the legacy of the Eastern Roman Empire. Ivan III married Sophia Palaiologina, the niece of the last Byzantine emperor Constantine XI, and made the Byzantine double-headed eagle his own, and eventually Russia's, coat-of-arms.

Tsardom of Russia

In development of the Third Rome ideas, the Grand Duke Ivan IV (the "Terrible")[39] was officially crowned first Tsar ("Caesar") of Russia in 1547. The Tsar promulgated a new code of laws (Sudebnik of 1550), established the first Russian feudal representative body (Zemsky Sobor) and introduced local self-management into the rural regions.[40][41]

During his long reign, Ivan the Terrible nearly doubled the already large Russian territory by annexing the three Tatar khanates (parts of the disintegrated Golden Horde): Kazan and Astrakhan along the Volga River, and the Siberian Khanate in southwestern Siberia. Thus, by the end of the 16th century Russia was transformed into a multiethnic, multidenominational and transcontinental state.

However, the Tsardom was weakened by the long and unsuccessful Livonian War against the coalition of Poland, Lithuania, and Sweden for access to the Baltic coast and sea trade.[42] At the same time, the Tatars of the Crimean Khanate, the only remaining successor to the Golden Horde, continued to raid Southern Russia.[43] In an effort to restore the Volga khanates, Crimeans and their Ottoman allies invaded central Russia and were even able to burn down parts of Moscow in 1571.[44] But in the next year the large invading army was thoroughly defeated by Russians in the Battle of Molodi, forever eliminating the threat of an Ottoman–Crimean expansion into Russia. The slave raids of Crimeans, however, did not cease until the late 17th century though the construction of new fortification lines across Southern Russia, such as the Great Abatis Line, constantly narrowed the area accessible to incursions.[45]

The death of Ivan's sons marked the end of the ancient Rurik Dynasty in 1598, and in combination with the famine of 1601–03[46] led to civil war, the rule of pretenders, and foreign intervention during the Time of Troubles in the early 17th century.[47] The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth occupied parts of Russia, including Moscow. In 1612, the Poles were forced to retreat by the Russian volunteer corps, led by two national heroes, merchant Kuzma Minin and Prince Dmitry Pozharsky. The Romanov Dynasty acceded to the throne in 1613 by the decision of Zemsky Sobor, and the country started its gradual recovery from the crisis.

Russia continued its territorial growth through the 17th century, which was the age of Cossacks. Cossacks were warriors organised into military communities, resembling pirates and pioneers of the New World. In 1648, the peasants of Ukraine joined the Zaporozhian Cossacks in rebellion against Poland-Lithuania during the Khmelnytsky Uprising in reaction to the social and religious oppression they had been suffering under Polish rule. In 1654, the Ukrainian leader, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, offered to place Ukraine under the protection of the Russian Tsar, Aleksey I. Aleksey's acceptance of this offer led to another Russo-Polish War. Finally, Ukraine was split along the Dnieper River, leaving the western part, right-bank Ukraine, under Polish rule and the eastern part (Left-bank Ukraine and Kiev) under Russian rule. Later, in 1670–71, the Don Cossacks led by Stenka Razin initiated a major uprising in the Volga Region, but the Tsar's troops were successful in defeating the rebels.

In the east, the rapid Russian exploration and colonisation of the huge territories of Siberia was led mostly by Cossacks hunting for valuable furs and ivory. Russian explorers pushed eastward primarily along the Siberian River Routes, and by the mid-17th century there were Russian settlements in Eastern Siberia, on the Chukchi Peninsula, along the Amur River, and on the Pacific coast. In 1648, the Bering Strait between Asia and North America was passed for the first time by Fedot Popov and Semyon Dezhnyov.[citation needed]

Imperial Russia

Under Peter the Great, Russia was proclaimed an Empire in 1721 and became recognised as a world power. Ruling from 1682 to 1725, Peter defeated Sweden in the Great Northern War, forcing it to cede West Karelia and Ingria (two regions lost by Russia in the Time of Troubles),[48] as well as Estland and Livland, securing Russia's access to the sea and sea trade.[49] On the Baltic Sea, Peter founded a new capital called Saint Petersburg, later known as Russia's "window to Europe". Peter the Great's reforms brought considerable Western European cultural influences to Russia.

The reign of Peter I's daughter Elizabeth in 1741–62 saw Russia's participation in the Seven Years' War (1756–63). During this conflict Russia annexed East Prussia for a while and even took Berlin. However, upon Elizabeth's death, all these conquests were returned to the Kingdom of Prussia by pro-Prussian Peter III of Russia.

Catherine II ("the Great"), who ruled in 1762–96, presided over the Age of Russian Enlightenment. She extended Russian political control over the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and incorporated most of its territories into Russia during the Partitions of Poland, pushing the Russian frontier westward into Central Europe. In the south, after successful Russo-Turkish Wars against Ottoman Turkey, Catherine advanced Russia's boundary to the Black Sea, defeating the Crimean Khanate. As a result of victories over Qajar Iran through the Russo-Persian Wars, by the first half of the 19th century Russia also made significant territorial gains in Transcaucasia and the North Caucasus, forcing the former to irrevocably cede what is nowadays Georgia, Dagestan, Azerbaijan and Armenia to Russia.[50][51] Catherine's successor, her son Paul, was unstable and focused predominantly on domestic issues. Following his short reign, Catherine's strategy was continued with Alexander I's (1801–25) wresting of Finland from the weakened kingdom of Sweden in 1809 and of Bessarabia from the Ottomans in 1812. At the same time, Russians colonised Alaska and even founded settlements in California, such as Fort Ross.

In 1803–1806, the first Russian circumnavigation was made, later followed by other notable Russian sea exploration voyages. In 1820, a Russian expedition discovered the continent of Antarctica.

In alliances with various European countries, Russia fought against Napoleon's France. The French invasion of Russia at the height of Napoleon's power in 1812 reached Moscow, but eventually failed miserably as the obstinate resistance in combination with the bitterly cold Russian winter led to a disastrous defeat of invaders, in which more than 95% of the pan-European Grande Armée perished.[52] Led by Mikhail Kutuzov and Barclay de Tolly, the Russian army ousted Napoleon from the country and drove through Europe in the war of the Sixth Coalition, finally entering Paris. Alexander I headed Russia's delegation at the Congress of Vienna that defined the map of post-Napoleonic Europe.

The officers of the Napoleonic Wars brought ideas of liberalism back to Russia with them and attempted to curtail the tsar's powers during the abortive Decembrist revolt of 1825. At the end of the conservative reign of Nicolas I (1825–55), a zenith period of Russia's power and influence in Europe was disrupted by defeat in the Crimean War. Between 1847 and 1851, about one million people died of Asiatic cholera.[53]

Nicholas's successor Alexander II (1855–81) enacted significant changes in the country, including the emancipation reform of 1861. These Great Reforms spurred industrialization and modernised the Russian army, which had successfully liberated Bulgaria from Ottoman rule in the 1877–78 Russo-Turkish War.

The late 19th century saw the rise of various socialist movements in Russia. Alexander II was killed in 1881 by revolutionary terrorists, and the reign of his son Alexander III (1881–94) was less liberal but more peaceful. The last Russian Emperor, Nicholas II (1894–1917), was unable to prevent the events of the Russian Revolution of 1905, triggered by the unsuccessful Russo-Japanese War and the demonstration incident known as Bloody Sunday. The uprising was put down, but the government was forced to concede major reforms (Russian Constitution of 1906), including granting the freedoms of speech and assembly, the legalization of political parties, and the creation of an elected legislative body, the State Duma of the Russian Empire. The Stolypin agrarian reform led to a massive peasant migration and settlement into Siberia. More than four million settlers arrived in that region between 1906 and 1914.[54]

February Revolution and Russian Republic

In 1914, Russia entered World War I in response to Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Russia's ally Serbia, and fought across multiple fronts while isolated from its Triple Entente allies. In 1916, the Brusilov Offensive of the Russian Army almost completely destroyed the military of Austria-Hungary. However, the already-existing public distrust of the regime was deepened by the rising costs of war, high casualties, and rumors of corruption and treason. All this formed the climate for the Russian Revolution of 1917, carried out in two major acts.

The February Revolution forced Nicholas II to abdicate; he and his family were imprisoned and later executed in Yekaterinburg during the Russian Civil War. The monarchy was replaced by a shaky coalition of political parties that declared itself the Provisional Government. On 1 September (14), 1917, upon a decree of the Provisional Government, the Russian Republic was proclaimed.[55] On 6 January (19), 1918, the Russian Constituent Assembly declared Russia a democratic federal republic (thus ratifying the Provisional Government's decision). The next day the Constituent Assembly was dissolved by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee.

Russian Civil War and Soviet power establishment

An alternative socialist establishment co-existed, the Petrograd Soviet, wielding power through the democratically elected councils of workers and peasants, called Soviets. The rule of the new authorities only aggravated the crisis in the country, instead of resolving it. Eventually, the October Revolution, led by Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin, overthrew the Provisional Government and gave full governing power to the Soviets, leading to the creation of the world's first socialist state.

Following the October Revolution, the Russian Civil War broke out between the anti-Communist White movement and the new Soviet regime with its Red Army. Bolshevist Russia lost its Ukrainian, Polish, Baltic, and Finnish territories by signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that concluded hostilities with the Central Powers of World War I. The Allied powers launched an unsuccessful military intervention in support of anti-Communist forces. In the meantime both the Bolsheviks and White movement carried out campaigns of deportations and executions against each other, known respectively as the Red Terror and White Terror. By the end of the civil war, Russia's economy and infrastructure were heavily damaged. There were an estimated 7–12 million casualties during the war, mostly civilians.[56] Millions became White émigrés,[57] and the Russian famine of 1921–22 claimed up to five million victims.[58]

Soviet Union

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (called Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic at the time), together with the Ukrainian, Byelorussian, and Transcaucasian Soviet Socialist Republics, formed the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), or Soviet Union, on 30 December 1922. Out of the 15 republics that would make up the USSR, the largest in size and over half of the total USSR population was the Russian SFSR, which came to dominate the union for its entire 69-year history.

Following Lenin's death in 1924, a troika was designated to govern the Soviet Union. However, Joseph Stalin, an elected General Secretary of the Communist Party, managed to suppress all opposition groups within the party and consolidate power in his hands to become the Soviet Union's de facto dictator by the 1930s. Leon Trotsky, the main proponent of world revolution, was exiled from the Soviet Union in 1929, and Stalin's idea of Socialism in One Country became the primary line. The continued internal struggle in the Bolshevik party culminated in the Great Purge, a period of mass repressions in 1937–38, during which hundreds of thousands of people were executed, including original party members and military leaders accused of coup d'état plots.[59]

Under Stalin's leadership, the government launched a command economy, industrialization of the largely rural country, and collectivization of its agriculture. During this period of rapid economic and social change, millions of people were sent to penal labor camps,[60] including many political convicts for their opposition to Stalin's rule; millions were deported and exiled to remote areas of the Soviet Union.[60] The transitional disorganisation of the country's agriculture, combined with the harsh state policies and a drought, led to the Soviet famine of 1932–1933,[61] which killed between 2 and 3 million people in the Russian SFSR.[62] The Soviet Union made the costly transformation from a largely agrarian economy to a major industrial powerhouse in a short span of time.

Under the doctrine of state atheism in the Soviet Union, there was a "government-sponsored program of forced conversion to atheism".[63][64][65] The Soviet government targeted religions based on state interests, and while most organised religions were never outlawed, religious property was confiscated, believers were harassed, and religion was ridiculed while atheism was propagated in schools.[66] In 1925 the government founded the League of Militant Atheists to intensify the persecution.[67] While persecution accelerated following Stalin's rise to power, a revival of Orthodoxy was fostered by the government during World War II and the Soviet authorities sought to control the Russian Orthodox Church rather than liquidate it.[68]

World War II

The Appeasement policy of Great Britain and France towards Adolf Hitler's annexation of Austria and Czechoslovakia did not stem an increase in the power of Nazi Germany. Around the same time, the Third Reich allied with the Empire of Japan, a rival of the USSR in the Far East and an open enemy of the USSR in the Soviet–Japanese Border Wars in 1938–39.[citation needed]

In August 1939, as attempts to form an anti-Nazi military alliance with Britain and France failed, the Soviet government signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany, pledging non-aggression between the two countries and secretly dividing Eastern Europe into their respective spheres of influence. When Germany launched the Invasion of Poland, the formally neutral Soviets followed weeks later with their own invasion of the country, claiming the eastern half of Poland. The Soviet government engaged in significant cooperation with Nazi Germany between 1939 and 1941, through extensive trade agreements which supplied Germany with vital raw materials for her war effort against Britain and France. As the other European powers were busy fighting in World War II, the USSR expanded her own military, and occupied the Hertza region as a result of the Winter War, annexed the Baltic states and annexed Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina from Romania.

On 22 June 1941, Nazi Germany broke their non-aggression treaty with their erstwhile partner and invaded the Soviet Union with the largest and most powerful invasion force in human history,[69] opening the largest theater of World War II. The Nazi Hunger Plan foresaw the "extinction of industry as well as a great part of the population".[70] Nearly 3 million Soviet POWs in German captivity were murdered in just eight months of 1941–42.[71] Although the German army had considerable early success, their attack was halted in the Battle of Moscow. Subsequently, the Germans were dealt major defeats first at the Battle of Stalingrad in the winter of 1942–43,[72] and then in the Battle of Kursk in the summer of 1943. Another German failure was the Siege of Leningrad, in which the city was fully blockaded on land between 1941 and 1944 by German and Finnish forces, and suffered starvation and more than a million deaths, but never surrendered.[73] Under Stalin's administration and the leadership of such commanders as Georgy Zhukov and Konstantin Rokossovsky, Soviet forces took Eastern Europe in 1944–45 and captured Berlin in May 1945. In August 1945 the Soviet Army ousted the Japanese from China's Manchukuo and North Korea, contributing to the allied victory over Japan.

The 1941–45 period of World War II is known in Russia as the "Great Patriotic War". The Soviet Union together with the United States, the United Kingdom and China were considered as the Big Four of Allied powers in World War II[75] and later became the Four Policemen which was the foundation of the United Nations Security Council.[76] During this war, which included many of the most lethal battle operations in human history, Soviet civilian and military death were about 27 million,[77][78] accounting for about a third of all World War II casualties. The full demographic loss to the Soviet peoples was even greater.[79] The Soviet economy and infrastructure suffered massive devastation which caused the Soviet famine of 1946–47,[80] but the Soviet Union emerged as an acknowledged military superpower on the continent.

Cold War

After the war, Eastern and Central Europe including East Germany and part of Austria was occupied by Red Army according to the Potsdam Conference. Dependent socialist governments were installed in the Eastern Bloc satellite states. Becoming the world's second nuclear weapons power, the USSR established the Warsaw Pact alliance and entered into a struggle for global dominance, known as the Cold War, with the United States and NATO. The Soviet Union supported revolutionary movements across the world, including the newly formed People's Republic of China, the Democratic People's Republic of Korea and, later on, the Republic of Cuba. Significant amounts of Soviet resources were allocated in aid to the other socialist states.[81]

After Stalin's death and a short period of collective rule, the new leader Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin and launched the policy of de-Stalinization. The penal labor system was reformed and many prisoners were released and rehabilitated (many of them posthumously).[82] The general easement of repressive policies became known later as the Khrushchev Thaw. At the same time, tensions with the United States heightened when the two rivals clashed over the deployment of the United States Jupiter missiles in Turkey and Soviet missiles in Cuba.

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched the world's first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, thus starting the Space Age. Russia's cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to orbit the Earth, aboard the Vostok 1 manned spacecraft on 12 April 1961.

Following the ousting of Khrushchev in 1964, another period of collective rule ensued, until Leonid Brezhnev became the leader. The era of the 1970s and the early 1980s was later designated as the Era of Stagnation, a period when economic growth slowed and social policies became static. The 1965 Kosygin reform aimed for partial decentralization of the Soviet economy and shifted the emphasis from heavy industry and weapons to light industry and consumer goods but was stifled by the conservative Communist leadership.

In 1979, after a Communist-led revolution in Afghanistan, Soviet forces entered that country. The occupation drained economic resources and dragged on without achieving meaningful political results. Ultimately, the Soviet Army was withdrawn from Afghanistan in 1989 due to international opposition, persistent anti-Soviet guerrilla warfare, and a lack of support by Soviet citizens.

From 1985 onwards, the last Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who sought to enact liberal reforms in the Soviet system, introduced the policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) in an attempt to end the period of economic stagnation and to democratise the government. This, however, led to the rise of strong nationalist and separatist movements. Prior to 1991, the Soviet economy was the second largest in the world,[83] but during its last years it was afflicted by shortages of goods in grocery stores, huge budget deficits, and explosive growth in the money supply leading to inflation.[84]

By 1991, economic and political turmoil began to boil over, as the Baltic states chose to secede from the Soviet Union. On 17 March, a referendum was held, in which the vast majority of participating citizens voted in favour of changing the Soviet Union into a renewed federation. In August 1991, a coup d'état attempt by members of Gorbachev's government, directed against Gorbachev and aimed at preserving the Soviet Union, instead led to the end of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. On 25 December 1991, the USSR was dissolved into 15 post-Soviet states.

Post-Soviet Russia (1991–present)

In June 1991, Boris Yeltsin became the first directly elected president in Russian history when he was elected President of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, which became the independent Russian Federation in December of that year. The economic and political collapse of the USSR led to a deep and prolonged depression, characterised by a 50% decline in both GDP and industrial output between 1990 and 1995, although some of the recorded declines may have been a result of an upward bias in Soviet-era economic data.[85][86] During and after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, wide-ranging reforms including privatization and market and trade liberalization were undertaken,[85] including radical changes along the lines of "shock therapy" as recommended by the United States and the International Monetary Fund.[87]

The privatization largely shifted control of enterprises from state agencies to individuals with inside connections in the government. Many of the newly rich moved billions in cash and assets outside of the country in an enormous capital flight.[88] The depression of the economy led to the collapse of social services; the birth rate plummeted while the death rate skyrocketed.[89] Millions plunged into poverty, from a level of 1.5% in the late Soviet era to 39–49% by mid-1993.[90] The 1990s saw extreme corruption and lawlessness, the rise of criminal gangs and violent crime.[91]

In late 1993, tensions between Yeltsin and the Russian parliament culminated in a constitutional crisis which ended after military force. Yeltsin found himself increasingly in conflict with the parliament, which resisted his policies, and on 21 September, he signed a decree dissolving the parliament and setting elections for a new bicameral legislature, overstepping his authority. Legislators barricaded themselves in the parliament building and voted to impeach Yeltsin. Clashes between anti-Yeltsin protesters and police broke out and armed demonstrators stormed the Moscow mayoral office and Ostankino Tower leading to Yeltsin to declare a state of emergency and to deploy the army on 4 October to attack the parliament building, where tanks fired rounds at the parliament building. The resistance leaders were then arrested and Yeltsin prevailed. During the crisis, Yeltsin was backed by Western governments and over 100 people were killed. In December, a constitutional referendum was held and approved which introduced a new constitution, giving the president enormous powers. Political scientist Hans-Henning Schröder argued that the day the new constitution was voted in was "the birthdate of a 'guided democracy' in Russia".[92][93]

The 1990s were plagued by armed conflicts in the North Caucasus, both local ethnic skirmishes and separatist Islamist insurrections. From the time Chechen separatists declared independence in the early 1990s, an intermittent guerrilla war has been fought between the rebel groups and the Russian military. Terrorist attacks against civilians carried out by separatists, most notably the Moscow theater hostage crisis and Beslan school siege, caused hundreds of deaths and drew worldwide attention.

Russia took up the responsibility for settling the USSR's external debts, even though its population made up just half of the population of the USSR at the time of its dissolution.[91] In 1992, most consumer price controls were eliminated, causing extreme inflation and significantly devaluing the Ruble.[94] With a devalued Ruble, the Russian government struggled to pay back its debts to internal debtors, as well as international institutions like the International Monetary Fund.[95] Despite significant attempts at economic restructuring, Russia's debt outpaced GDP growth. High budget deficits coupled with increasing capital flight and inability to pay back debts[96] caused the 1998 Russian financial crisis[94] and resulted in a further GDP decline.[84]

Putin-era

On 31 December 1999, President Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned, handing the post to the recently appointed Prime Minister, Vladimir Putin. Yeltsin left office widely unpopular, with an approval rating as low as 2% by some estimates.[97] Putin then won the 2000 presidential election and suppressed the Chechen insurgency although sporadic violence still occurs throughout the Northern Caucasus. High oil prices and the initially weak currency followed by increasing domestic demand, consumption, and investments helped the economy grow at an average of 7% per year from 1998 to 2008,[98] improving the standard of living and increasing Russia's influence on the world stage.[99] Putin went on to win a second presidential term in 2004. Following the world economic crisis of 2008 and a subsequent drop in oil prices, Russia's economy stagnated and poverty again started to rise[100] until 2017 when, after the prolonged recession, Russia's economy began to grow again, supported by stronger global growth, higher oil prices, and solid macro fundamentals.[100] While many reforms made during the Putin presidency have been generally criticised by Western nations as undemocratic,[101] Putin's leadership over the return of order, stability, and progress has won him widespread admiration in Russia.[102]

On 2 March 2008, Dmitry Medvedev was elected President of Russia while Putin became Prime Minister. The Constitution of Russia prohibited Putin from serving a third consecutive presidential term. Putin returned to the presidency following the 2012 presidential elections, and Medvedev was appointed Prime Minister. This quick succession in leadership change was coined "tandemocracy" by outside media. Some critics claimed that the leadership change was superficial, and that Putin remained as the decision making force in the Russian government, while other political analysts viewed it as truly tandem.[103][104] Alleged fraud in the 2011 parliamentary elections and Putin's return to the presidency in 2012 sparked mass protests.[105]

In 2014, after President Viktor Yanukovych of Ukraine fled as a result of a revolution, Putin requested and received authorization from the Russian parliament to deploy Russian troops to Ukraine, leading to the takeover of Crimea.[106][107] Following a Crimean referendum in which separation was favoured by a large majority of voters,[108][109] the Russian leadership announced the accession of Crimea into the Russian Federation, though this and the referendum that preceded it were not accepted internationally.[110] The annexation of Crimea led to sanctions by Western countries, in which the Russian government responded with its own against a number of countries.[111][112]

In September 2015, Russia started military intervention in the Syrian Civil War in support of the Syrian government, consisting of air strikes against militant groups of the Islamic State, al-Nusra Front (al-Qaeda in the Levant), the Army of Conquest and other rebel groups.

In 2018, Putin was elected for a fourth presidential term overall. In January 2020, substantial amendments to the Constitution of Russia were proposed and took effect in July following a national vote, allowing Putin to run for two more six-year presidential terms after his current term ends.[113] The vote was originally scheduled for April, but was postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Russia.[114] As of November 2020, over 2 million cases were confirmed.[115]

Politics

is the main location of where Russian political affairs take place

Governance

|

|

| Vladimir Putin |

Mikhail Mishustin |

According to the Constitution of Russia, the country is an asymmetric federation and semi-presidential republic, wherein the President is the head of state[116] and the Prime Minister is the head of government. The Russian Federation is fundamentally structured as a multi-party representative democracy, with the federal government composed of three branches:

- Legislative: The bicameral Federal Assembly of Russia, made up of the 450-member State Duma and the 170-member Federation Council, adopts federal law, declares war, approves treaties, has the power of the purse and the power of impeachment of the President.

- Executive: The President is the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, can veto legislative bills before they become law, and appoints the Government of Russia (Cabinet) and other officers, who administer and enforce federal laws and policies.

- Judiciary: The Constitutional Court, Supreme Court and lower federal courts, whose judges are appointed by the Federation Council on the recommendation of the President, interpret laws and can overturn laws they deem unconstitutional.

The president is elected by popular vote for a six-year term (eligible for a second term, but not for a third consecutive term).[117] Ministries of the government are composed of the Premier and his deputies, ministers, and selected other individuals; all are appointed by the President on the recommendation of the Prime Minister (whereas the appointment of the latter requires the consent of the State Duma).

Foreign relations

The Russian Federation is recognised in international law as a successor state of the former Soviet Union.[118] Russia continues to implement the international commitments of the USSR, and has assumed the USSR's permanent seat in the UN Security Council, membership in other international organisations, the rights and obligations under international treaties, and property and debts. Russia has a multifaceted foreign policy. As of 2009[update], it maintains diplomatic relations with 191 countries and has 144 embassies. The foreign policy is determined by the President and implemented by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia.[119]

Although it is the successor state to a former superpower, Russia is commonly accepted to be a great power, as well as a regional power. It is one of five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. The country participates in the Quartet on the Middle East and the Six-party talks with North Korea. Russia is a member of the Council of Europe, OSCE, and APEC. Russia usually takes a leading role in regional organisations such as the CIS, EurAsEC, CSTO, and the SCO.[120] Russia became the 39th member state of the Council of Europe in 1996.[121] In 1998, Russia ratified the European Convention on Human Rights. The legal basis for EU relations with Russia is the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement, which came into force in 1997. The Agreement recalls the parties' shared respect for democracy and human rights, political and economic freedom and commitment to international peace and security.[122] In May 2003, the EU and Russia agreed to reinforce their cooperation on the basis of common values and shared interests.[123] President Vladimir Putin had advocated a strategic partnership with close integration in various dimensions, including establishment of EU-Russia Common Spaces.[124] From the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia has initially developed a friendlier relationship with the United States and NATO, however today, the trilateral relationship has significantly deteriorated due to several issues and conflicts between Russia and the Western countries.[125][126] The NATO-Russia Council was established in 2002 to allow the United States, Russia and the 27 allies in NATO to work together as equal partners to pursue opportunities for joint collaboration.[127]

Russia maintains strong and positive relations with other SCO and BRICS countries.[128][129] In recent years, the country has significantly strengthened bilateral ties with the People's Republic of China by signing the Treaty of Friendship as well as building the Trans-Siberian oil pipeline and gas pipeline from Siberia to China, and has since formed a special relationship with China.[130][131] India is the largest customer of Russian military equipment and the two countries share extensive defence and strategic relations.[132]

Military

The Russian Armed Forces are divided into the Ground Forces, Navy, and Air Force. There are also three independent arms of service: Strategic Missile Troops, Aerospace Defence Forces, and the Airborne Troops. As of 2017[update], the military comprised over one million active duty personnel, the fifth-largest in the world.[133] Additionally, there are over 2.5 million reservists, with the total number of reserve troops possibly being as high as 20 million.[134] It is mandatory for all male citizens aged 18–27 to be drafted for a year of service in Armed Forces.[99]

Russia boasts the world's second-most powerful military,[135] and is among the five recognized nuclear-weapons states, with the largest stockpile of nuclear weapons in the world. More than half of the world's 14,000 nuclear weapons are owned by Russia.[136] The country possesses the second-largest fleet of ballistic missile submarines, and is one of the only three states operating strategic bombers, with the world's most powerful tank force,[137] the second-most powerful air force,[138] and the third-most powerful navy fleet.[139] According to SIPRI estimates, Russia has the highest military expenditure in Europe, and the fourth-highest in the world, with a budget of $65.1 billion, or 3.9% of its total GDP.[140]

Russia has a large and fully indigenous arms industry, producing most of its own military equipment with only a few types of weapons imported. It has been one of the world's top supplier of arms since 2001, accounting for around 30% of worldwide weapons sales.[141] In 2020, according to a research from SIPRI, Russia is the third-biggest exporters of arms in the world, behind only the United States and China.[142]

Human rights

This section may lend undue weight to section not based on academic publications but rather media reports . Please help to create a more balanced presentation. Discuss and resolve this issue before removing this message. (January 2021) |

The Russian constitution grants numerous de jure protections to human rights for its citizens, such as the precedence of international law over federal legislation, which includes how Russia has ratified by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Since the reelection of Vladimir Putin as President in 2004, Russia's human rights management has been increasingly criticized by leading democracy and human rights watchdogs. In particular, such organisations as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch consider Russia to have not enough democratic attributes and to allow few political rights and civil liberties to its citizens.[143][144] Freedom House, an international organisation funded by the United States, ranks Russia as "not free", citing "carefully engineered elections" and "absence" of debate.[145]

Media freedom has been consistently rated no higher than 140th out of between 167-180 countries in Reporters Without Borders' annual Press Freedom Index rankings since 2006, citing in 2020 that pressure on independent media has steadily increased since major anti-government protests from 2011-2013, and that independent journalists who question the neoconservative and patriotic discourse vehemently spread by Russian state media have fallen under a climate of oppression. RSF also reported that murders and attacks against journalists remain under impunity, while selectively applied anti-extremism laws as well as territorial sovereignty grounds have been used to arrest journalists and bloggers.[146] Elections in Russia have also been increasingly characterized as unfair by foreign observers, which have often had favorable results for Putin and his political allies, in not only the federal but also the regional and municipal levels.[147] Freedom of assembly is also guaranteed by the Russian constitution, but in practice, the Russian government has generally not respected this right and has violently cracked down on mass protests.

Systematic torture and abuse have also been documented in various Russian state institutions. These have included the imprisonment and abuse of people determined to be problematic for Russian authorities in psychiatric institutions.[148] In 2019, Human Rights Watch alleged that torture remained widespread, particularly in pretrial detention centers and prisons. Russian authorities often deny the existence of ill-treatment in their jurisdictions and accordingly take little if any action against its suspected perpetrators.[149] Despite reforms being made in 2010 to conscription in the Russian military to tackle dedovshchina or the systematic abuse and hazing of junior conscripts in the Russian military and other security apparatuses, a legacy of the Soviet Union that has also been documented in some other post-soviet republics, the military NGO the Mother's Right Foundation estimates that 44% of conscript deaths are due to suicide while only 4% happen in the line of duty.[150]

The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs called the 2006 Freedom in the World report "prefabricated", stating that the human rights issues have been turned into a political weapon in particular by the United States. The ministry also claims that such organisations as Freedom House and Human Rights Watch use the same scheme of voluntary extrapolation of "isolated facts that of course can be found in any country" into "dominant tendencies".[151] Putin has argued that Western-style liberalism is obsolete in Russia, while maintaining that the country is still a democratic nation.[152][153][154]

Corruption

According to the Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index, Russia ranked 137th out of 180 countries, and was considered the most corrupt European country in 2019.[155][156][157] Corruption in Russia is perceived as a significant problem,[158] impacting all aspects of life, including economy,[159] business,[160] public administration,[161][162] law enforcement,[163] healthcare,[164] and education.[165] The phenomenon of corruption is strongly established in the historical model of public governance in Russia and attributed to general weakness of rule of law in Russia.[161][166]

Political divisions

- Federal subjects

According to the Constitution, the country comprises eighty-five federal subjects,[167] including the disputed Republic of Crimea and federal city of Sevastopol.[168] In 1993, when the Constitution was adopted, there were eighty-nine federal subjects listed, but later some of them were merged. These subjects have equal representation—two delegates each—in the Federation Council.[169] However, they differ in the degree of autonomy they enjoy.

- 46 oblasts (provinces): most common type of federal subjects, with locally elected governor and legislature.[170]

- 22 republics: nominally autonomous; each is tasked with drafting its own constitution, direct-elected[170] head of republic[171] or a similar post, and parliament. Republics are allowed to establish their own official language alongside Russian but are represented by the federal government in international affairs. Republics are meant to be home to specific ethnic minorities.

- 9 krais (territories): essentially the same as oblasts. The "territory" designation is historic, originally given to frontier regions and later also to the administrative divisions that comprised autonomous okrugs or autonomous oblasts.

- 4 autonomous okrugs (autonomous districts): originally autonomous entities within oblasts and krais created for ethnic minorities, their status was elevated to that of federal subjects in the 1990s. With the exception of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, all autonomous okrugs are still administratively subordinated to a krai or an oblast of which they are a part.

- 1 autonomous oblast (the Jewish Autonomous Oblast): historically, autonomous oblasts were administrative units subordinated to krais. In 1990, all of them except for the Jewish AO were elevated in status to that of a republic.

- 3 federal cities (Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and Sevastopol): major cities that function as separate regions.

- Federal districts

Federal subjects are grouped into eight federal districts, each administered by an envoy appointed by the President of Russia.[172] Unlike the federal subjects, the federal districts are not a subnational level of government, but are a level of administration of the federal government. Federal districts' envoys serve as liaisons between the federal subjects and the federal government and are primarily responsible for overseeing the compliance of the federal subjects with the federal laws.[citation needed]

Geography

Russia is the largest country in the world; its total area is 17,075,200 square kilometres (6,592,800 sq mi).[173][174] This makes it larger than the continents of Oceania, Europe and Antarctica. It lies between latitudes 41° and 82° N, and longitudes 19° E and 169° W.

Russia's territorial expansion was achieved largely in the late 16th century under the Cossack Yermak Timofeyevich during the reign of Ivan the Terrible, at a time when competing city-states in the western regions of Russia had banded together to form one country. Yermak mustered an army and pushed eastward where he conquered nearly all the lands once belonging to the Mongols, defeating their ruler, Khan Kuchum.[175]

Russia has a wide natural resource base, including major deposits of timber, petroleum, natural gas, coal, ores and other mineral resources.

Topography

The two most widely separated points in Russia are about 8,000 km (4,971 mi) apart along a geodesic line. These points are: a 60 km (37 mi) long Vistula Spit the boundary with Poland separating the Gdańsk Bay from the Vistula Lagoon and the most southeastern point of the Kuril Islands. The points which are farthest separated in longitude are 6,600 km (4,101 mi) apart along a geodesic line. These points are: in the west, the same spit on the boundary with Poland, and in the east, the Big Diomede Island. The Russian Federation spans 11 time zones.

Most of Russia consists of vast stretches of plains that are predominantly steppe to the south and heavily forested to the north, with tundra along the northern coast. Russia possesses 7.4% of the world's arable land.[176] Mountain ranges are found along the southern borders, such as the Caucasus (containing Mount Elbrus, which at 5,642 m (18,510 ft) is the highest point in both Russia and Europe) and the Altai (containing Mount Belukha, which at the 4,506 m (14,783 ft) is the highest point of Siberia outside of the Russian Far East); and in the eastern parts, such as the Verkhoyansk Range or the volcanoes of Kamchatka Peninsula (containing Klyuchevskaya Sopka, which at the 4,750 m (15,584 ft) is the highest active volcano in Eurasia as well as the highest point of Siberia). The Ural Mountains, rich in mineral resources, form a north–south range that divides Europe and Asia.

Russia has an extensive coastline of over 37,000 km (22,991 mi) along the Arctic and Pacific Oceans, as well as along the Baltic Sea, Sea of Azov, Black Sea and Caspian Sea.[99] The Barents Sea, White Sea, Kara Sea, Laptev Sea, East Siberian Sea, Chukchi Sea, Bering Sea, Sea of Okhotsk, and the Sea of Japan are linked to Russia via the Arctic and Pacific. Russia's major islands and archipelagos include Novaya Zemlya, the Franz Josef Land, the Severnaya Zemlya, the New Siberian Islands, Wrangel Island, the Kuril Islands, and Sakhalin. The Diomede Islands (one controlled by Russia, the other by the United States) are just 3 km (1.9 mi) apart, and Kunashir Island is about 20 km (12.4 mi) from Hokkaido, Japan.

Russia has thousands of rivers and inland bodies of water, providing it with one of the world's largest surface water resources. Its lakes contain approximately one-quarter of the world's liquid fresh water.[177] The largest and most prominent of Russia's bodies of fresh water is Lake Baikal, the world's deepest, purest, oldest and most capacious fresh water lake.[178] Baikal alone contains over one-fifth of the world's fresh surface water.[177] Other major lakes include Ladoga and Onega, two of the largest lakes in Europe. Russia is second only to Brazil in volume of the total renewable water resources. Of the country's 100,000 rivers,[179] the Volga is the most famous, not only because it is the longest river in Europe, but also because of its major role in Russian history.[99] The Siberian rivers of Ob, Yenisey, Lena and Amur are among the longest rivers in the world.

Climate

The enormous size of Russia and the remoteness of many areas from the sea result in the dominance of the humid continental climate, which is prevalent in all parts of the country except for the tundra and the extreme southwest. Mountains in the south obstruct the flow of warm air masses from the Indian Ocean, while the plain of the west and north makes the country open to Arctic and Atlantic influences.[180]

Most of Northern European Russia and Siberia has a subarctic climate, with extremely severe winters in the inner regions of Northeast Siberia (mostly the Sakha Republic, where the Northern Pole of Cold is located with the record low temperature of −71.2 °C or −96.2 °F), and more moderate winters elsewhere. Both the strip of land along the shore of the Arctic Ocean and the Russian Arctic islands have a polar climate.

The coastal part of Krasnodar Krai on the Black Sea, most notably in Sochi, possesses a humid subtropical climate with mild and wet winters. In many regions of East Siberia and the Far East, winter is dry compared to summer; other parts of the country experience more even precipitation across seasons. Winter precipitation in most parts of the country usually falls as snow. The region along the Lower Volga and Caspian Sea coast, as well as some areas of southernmost Siberia, possesses a semi-arid climate.

Throughout much of the territory there are only two distinct seasons—winter and summer—as spring and autumn are usually brief periods of change between extremely low and extremely high temperatures.[180] The coldest month is January (February on the coastline); the warmest is usually July. Great ranges of temperature are typical. In winter, temperatures get colder both from south to north and from west to east. Summers can be quite hot, even in Siberia.[181] The continental interiors are the driest areas.[citation needed]

Biodiversity

From north to south the East European Plain, also known as Russian Plain, is clad sequentially in Arctic tundra, coniferous forest (taiga), mixed and broad-leaf forests, grassland (steppe), and semi-desert (fringing the Caspian Sea), as the changes in vegetation reflect the changes in climate. Siberia supports a similar sequence but is largely taiga. Russia has the world's largest forest reserves,[182] known as "the lungs of Europe",[183] second only to the Amazon Rainforest in the amount of carbon dioxide it absorbs.

In 2019, Russia had a mean score of 9.02/10 in the Forest Landscape Integrity Index, ranking it 10th globally out of 172 countries.[184]

There are 266 mammal species and 780 bird species in Russia. A total of 415 animal species have been included in the Red Data Book of the Russian Federation as of 1997 and are now protected.[185] There are 28 UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Russia,[186] 40 UNESCO biosphere reserves,[187] 41 national parks and 101 nature reserves. Russia still has many ecosystems which are still untouched by man— mainly in the northern areas taiga and in subarctic tundra of Siberia. Over time Russia has been having improvement and application of environmental legislation, development and implementation of various federal and regional strategies and programmes, and study, inventory and protection of rare and endangered plants, animals, and other organisms, and including them in the Red Data Book of the Russian Federation.[188]

Economy

Russia has an upper-middle income mixed economy,[189] with enormous natural resources, particularly oil and natural gas. It has the world's eleventh-largest economy by nominal GDP and the sixth-largest by PPP. Since the turn of the 21st century, higher domestic consumption and greater political stability have bolstered economic growth in Russia. The country ended 2008 with its ninth straight year of growth, but growth has slowed with the decline in the price of oil and gas. According to the World Bank, Russia's GDP per capita by PPP was $29,181 in 2019.[190] Growth was primarily driven by non-traded services and goods for the domestic market, as opposed to oil or mineral extraction and exports.[99] The average nominal salary in Russia was ₽47,867 per month in 2019,[191] and approximately 12.9% of Russians lived below the national poverty line in 2018.[192] Unemployment in Russia was 4.5% in 2019,[193] and officially more than 70% of the Russian population is categorised as middle class;[194] though some experts disagree with that.[195][196][197][198]

By the end of December 2019, Russian foreign trade turnover reached $666.6 billion. Russia's exports totalled over $422.8 billion, while its imported goods were worth over $243.8 billion.[199]

Oil, natural gas, metals, and timber account for more than 80% of Russian exports abroad.[99] Since 2003, the exports of natural resources started decreasing in economic importance as the internal market strengthened considerably. As of 2012[update] the oil-and-gas sector accounted for 16% of GDP, 52% of federal budget revenues and over 80% of total exports.[200][201] Oil export earnings allowed Russia to increase its foreign reserves from $12 billion in 1999 to $597.3 billion on 1 August 2008. As of August 2020[update], foreign reserves in Russia are $438 billion.[202] The macroeconomic policy under Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin was prudent and sound, with excess income being stored in the Stabilization Fund of Russia.[203] In 2006, Russia repaid most of its formerly massive debts,[204] leaving it with one of the lowest foreign debts among major economies.[205] The Stabilization Fund helped Russia to come out of the global financial crisis in a much better state than many experts had expected.[203]

A simpler, more streamlined tax code adopted in 2001 reduced the tax burden on people and dramatically increased state revenue.[206] Russia has a flat tax rate of 13%. This ranks it as the country with the second most attractive personal tax system for single managers in the world after the United Arab Emirates.[207] The country has the highest proportion of higher education graduates in the world.[208][needs update]

The average inflation in Russia was 4.48% in 2019.[209] Inequality of household income and wealth has also been noted, with Credit Suisse finding Russian wealth distribution so much more extreme than other countries studied it "deserves to be placed in a separate category."[210][211]

Energy

In recent years, Russia has frequently been described in the media as an energy superpower.[212][213] The country has the world's largest natural gas reserves,[214] the second-largest coal reserves,[215] the eighth-largest oil reserves,[216] and the largest oil shale reserves in Europe.[217] Russia is the world's leading natural gas exporter,[218] the second-largest natural gas producer,[219] the second-largest oil exporter,[220] and the third-largest oil producer.[221] Fossil fuels cause most of the greenhouse gas emissions by Russia.[222]

Russia is the fourth-largest electricity producer in the world,[223] and the ninth-largest renewable energy producer in 2019.[224]

Russia was the first country to develop civilian nuclear power and to construct the world's first nuclear power plant. In 2019, the country was the fourth-largest nuclear energy producer in the world; nuclear generated 20% of the country's electricity.[225]

In 2014 Russia signed a deal to supply China with 38 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year. The project, which President Putin has called the "world's biggest construction project," was launched in 2019 and is expected continue for 30 years at an ultimate cost to China of $400 billion.[226]

Tourism

According to a UNWTO report, Russia is the sixteenth-most visited country in the world, and the tenth-most visited country in Europe, as of 2018, with 24.6 million visits.[227] Russia is the 39th in the Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019.[228] According to Federal Agency for Tourism, the number of inbound trips of foreign citizens to Russia amounted to 24.4 million in 2019.[229] Russia's international tourism receipts in 2018 amounted to $11.6 billion.[227] In 2020, tourism accounted for about 4% of country's GDP.[230] Major tourist routes in Russia include a journey around the Golden Ring theme route of ancient cities, cruises on the big rivers like the Volga, and journeys on the famous Trans-Siberian Railway.[231] Russia's most visited and popular landmarks include Red Square, the Peterhof Palace, the Kazan Kremlin, the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius and Lake Baikal.[232]

Agriculture

Russia's total area of cultivated land is estimated at 1,237,294 square kilometres (477,722 sq mi), the fourth largest in the world.[233] From 1999 to 2009, Russia's agriculture grew steadily,[234] and the country turned from a grain importer to the third largest grain exporter after the EU and the United States.[235] The production of meat has grown from 6,813,000 tonnes in 1999 to 9,331,000 tonnes in 2008, and continues to grow.[236]

The 2014 devaluation of the rouble and imposition of sanctions spurred domestic production, and in 2016 Russia exceeded Soviet grain production levels,[237] and became the world's largest exporter of wheat.[238]

This restoration of agriculture was supported by a credit policy of the government, helping both individual farmers and large privatised corporate farms that once were Soviet kolkhozes and which still own the significant share of agricultural land.[239] While large farms concentrate mainly on grain production and husbandry products, small private household plots produce most of the country's potatoes, vegetables and fruits.[240]

Since Russia borders three oceans (the Atlantic, Arctic, and Pacific), Russian fishing fleets are a major world fish supplier. Russia captured 3,191,068 tons of fish in 2005.[241] Both exports and imports of fish and sea products grew significantly in recent years, reaching $2,415 and $2,036 million, respectively, in 2008.[242]

Sprawling from the Baltic Sea to the Pacific Ocean, Russia has more than a fifth of the world's forests, which makes it the largest forest country in the world.[182][243] However, according to a 2012 study by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the Government of the Russian Federation,[244] the considerable potential of Russian forests is underutilised and Russia's share of the global trade in forest products is less than four percent.[245]

Transport

Railway transport in Russia is mostly under the control of the state-run Russian Railways monopoly. The company accounts for over 3.6% of Russia's GDP and handles 39% of the total freight traffic (including pipelines) and more than 42% of passenger traffic.[246] The total length of common-used railway tracks exceeds 85,500 km (53,127 mi),[246] second only to the United States. Over 44,000 km (27,340 mi) of tracks are electrified,[247] which is the largest number in the world, and additionally there are more than 30,000 km (18,641 mi) of industrial non-common carrier lines. Railways in Russia, unlike in the most of the world, use broad gauge of 1,520 mm (4 ft 11 27⁄32 in), with the exception of 957 km (595 mi) on Sakhalin island using narrow gauge of 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in). The most renowned railway in Russia is Trans-Siberian (Transsib), spanning a record seven time zones and serving the longest single continuous services in the world, Moscow-Vladivostok (9,259 km (5,753 mi)), Moscow–Pyongyang (10,267 km (6,380 mi))[248] and Kyiv–Vladivostok (11,085 km (6,888 mi)).[249]

As of 2006[update] Russia had 933,000 km of roads, of which 755,000 were paved.[250] Some of these make up the Russian federal motorway system. With a large land area the road density is the lowest of all the G8 and BRIC countries.[251]

Much of Russia's inland waterways, which total 102,000 km (63,380 mi), are made up of natural rivers or lakes. In the European part of the country the network of channels connects the basins of major rivers. Russia's capital, Moscow, is sometimes called "the port of the five seas", because of its waterway connections to the Baltic, White, Caspian, Azov and Black Seas.

Major sea ports of Russia include Rostov-on-Don on the Azov Sea, Novorossiysk on the Black Sea, Astrakhan and Makhachkala on the Caspian, Kaliningrad and St Petersburg on the Baltic, Arkhangelsk on the White Sea, Murmansk on the Barents Sea, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky and Vladivostok on the Pacific Ocean. In 2008 the country owned 1,448 merchant marine ships. The world's only fleet of nuclear-powered icebreakers advances the economic exploitation of the Arctic continental shelf of Russia and the development of sea trade through the Northern Sea Route between Europe and East Asia.

By total length of pipelines Russia is second only to the United States. Currently many new pipeline projects are being realised, including Nord Stream and South Stream natural gas pipelines to Europe, and the Eastern Siberia – Pacific Ocean oil pipeline (ESPO) to the Russian Far East and China.

Russia has 1,216 airports,[253] the busiest being Sheremetyevo, Domodedovo, and Vnukovo in Moscow, and Pulkovo in St. Petersburg.

Typically, major Russian cities have well-developed systems of public transport, with the most common varieties of exploited vehicles being bus, trolleybus and tram. Seven Russian cities, namely Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Nizhny Novgorod, Novosibirsk, Samara, Yekaterinburg, and Kazan, have underground metros, while Volgograd features a metrotram. The total length of metros in Russia is 465.4 kilometres (289.2 mi). Moscow Metro and Saint Petersburg Metro are the oldest in Russia, opened in 1935 and 1955 respectively. These two are among the fastest and busiest metro systems in the world, and some of them are famous for rich decorations and unique designs of their stations,[254] which is a common tradition in Russian metros and railways.[255]

Science and technology

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

In 2019 Russia spent approximately 422 billion rubles on domestic research and development, of which 60-70% was provided by the federal government.[256] Since 1904, Nobel Prize were awarded to twenty-six Russian and Soviet people in physics, chemistry, medicine, economy, literature and peace.[257] In 2019 Russia was ranked tenth worldwide in a number of scientific publications ranking.[258] Russia has around 118 million internet users, equivalent to around 81% of its total January 2020 population.[259]

Science and technology in Russia blossomed since the Age of Enlightenment, when Peter the Great founded the Russian Academy of Sciences and Saint Petersburg State University, and polymath Mikhail Lomonosov established the Moscow State University, paving the way for a strong native tradition in learning and innovation. In the 19th and 20th centuries the country produced a large number of notable scientists and inventors.

The Russian physics school began with Lomonosov who proposed the law of conservation of matter preceding the energy conservation law. Russian discoveries and inventions in physics include the electric arc, electrodynamical Lenz's law, space groups of crystals, photoelectric cell, superfluidity, Cherenkov radiation, electron paramagnetic resonance, heterotransistors and 3D holography. Lasers and masers were co-invented by Nikolai Basov and Alexander Prokhorov, while the idea of tokamak for controlled nuclear fusion was introduced by Igor Tamm, Andrei Sakharov and Lev Artsimovich, leading eventually the modern international ITER project, where Russia is a party.

Since the time of Nikolay Lobachevsky (the "Copernicus of Geometry" who pioneered the non-Euclidean geometry) and a prominent tutor Pafnuty Chebyshev, the Russian mathematical school became one of the most influential in the world.[260] Chebyshev's students included Aleksandr Lyapunov, who founded the modern stability theory, and Andrey Markov who invented the Markov chains. In the 20th century Soviet mathematicians, such as Andrey Kolmogorov, Israel Gelfand, and Sergey Sobolev, made major contributions to various areas of mathematics. Nine Soviet/Russian mathematicians were awarded with the Fields Medal, a most prestigious award in mathematics. Recently Grigori Perelman was offered the first ever Clay Millennium Prize Problems Award for his final proof of the Poincaré conjecture in 2002.[261]

Russian chemist Dmitry Mendeleev invented the Periodic table, the main framework of modern chemistry. Aleksandr Butlerov was one of the creators of the theory of chemical structure, playing a central role in organic chemistry. Russian biologists include Dmitry Ivanovsky who discovered viruses, Ivan Pavlov who was the first to experiment with the classical conditioning, and Ilya Mechnikov who was a pioneer researcher of the immune system and probiotics.

Many Russian scientists and inventors were émigrés, like Igor Sikorsky, who built the first airliners and modern-type helicopters; Vladimir Zworykin, often called the father of television; chemist Ilya Prigogine, noted for his work on dissipative structures and complex systems; Nobel Prize-winning economists Simon Kuznets and Wassily Leontief; physicist Georgiy Gamov (an author of the Big Bang theory) and social scientist Pitirim Sorokin. Many foreigners worked in Russia for a long time, like Leonard Euler and Alfred Nobel.

Russian inventions include arc welding by Nikolay Benardos, further developed by Nikolay Slavyanov, Konstantin Khrenov and other Russian engineers. Gleb Kotelnikov invented the knapsack parachute, while Evgeniy Chertovsky introduced the pressure suit. Alexander Lodygin and Pavel Yablochkov were pioneers of electric lighting, and Mikhail Dolivo-Dobrovolsky introduced the first three-phase electric power systems, widely used today. Sergei Lebedev invented the first commercially viable and mass-produced type of synthetic rubber. The first ternary computer, Setun, was developed by Nikolay Brusentsov.

In the 20th century a number of prominent Soviet aerospace engineers, inspired by the fundamental works of Nikolai Zhukovsky, Sergei Chaplygin and others, designed many hundreds of models of military and civilian aircraft and founded a number of KBs (Construction Bureaus) that now constitute the bulk of Russian United Aircraft Corporation. Famous Russian aircraft include the civilian Tu-series, Su and MiG fighter aircraft, Ka and Mi-series helicopters; many Russian aircraft models are on the list of most produced aircraft in history.

Famous Russian battle tanks include T34, the most heavily produced tank design of World War II,[262] and further tanks of T-series, including the most produced tank in history, T54/55.[263] The AK47 and AK74 by Mikhail Kalashnikov constitute the most widely used type of assault rifle throughout the world—so much so that more AK-type rifles have been manufactured than all other assault rifles combined.[264]

With all these achievements, however, since the late Soviet era Russia was lagging behind the West in a number of technologies, mostly those related to energy conservation and consumer goods production. The crisis of the 1990s led to the drastic reduction of the state support for science and a brain drain migration from Russia.

In the 2000s, on the wave of a new economic boom, the situation in the Russian science and technology has improved, and the government launched a campaign aimed into modernisation and innovation. Russian President Dmitry Medvedev formulated top priorities for the country's technological development:

- Efficient energy use

- Information technology, including both common products and the products combined with space technology

- Nuclear energy