Christian ethics

Christian ethics, also called Moral theology, was a branch of theology for most of its history. It separated from theology during the Enlightenment of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and for most scholars of the twenty-first century, it holds a niche between theology on one side and the social sciences on the other. The Christian ethical system is both a virtue ethic, which focuses on the building of an ethical character and what kind of person we ought to be, and a deontological ethic, which assesses choices and what we ought to do.

Christian ethics originated during the period of Early Christianity between AD27-30 and AD325. It continued to develop throughout the middle ages when the rediscovery of Aristotle led to scholasticism and the writings of Thomas Aquinas. The Reformation, Counter-Reformation and Christian humanism all had a lasting impact on Christian ethics and its political and economic teachings. Modern Christian ethics has been heavily impacted by the loss of its connection to theology and by secularism.

Christian ethics takes its metaphysical core from the Bible, seeing God as the ultimate source of all power. Evidential, Reformed and volitional epistemology are the three most common forms of Christian epistemology. Since the Bible is the foundation of Christian ethics, and the Bible has a variety of ethical perspectives, there has been disagreement over the basic ethical principles of Christian ethics from its beginnings with seven of them requiring perennial reinterpretation. Christian ethicists use reason, natural law, the social sciences and the Bible to argue modern interpretations. The Christian ethical system is applied to every area of life, and its principles are used to make decisions concerning politics, relationships, bioethics, environmental ethics and more.

Definition and sources[edit]

Christian ethics, also called Moral theology, was a branch of theology for most of its history.[2]:15 As a field of study, it was separated from theology during the Enlightenment of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and for most scholars of the twenty-first century, it has become a "discipline of reflection and analysis that lies between theology on one side and the social sciences on the other".[3]:41[4] The Christian ethical system is both a virtue ethic, which focuses on the building of an ethical character, and it is also a deontological ethic which assesses choices as morally required, forbidden, or permitted. These two approaches are normally seen as contrasting with one another,[5] yet within the Christian ethical system, they are combined.[6][7]

Theologian Joseph Sittler is quoted as saying the Christian ethic can be defined as "faith doing".[8]:7 According to theologian Servais Pinckaers, "everyone admits [that] Christians ethics is the branch of theology that studies human acts so as to direct them to a loving vision of God seen as our true, complete happiness and our final end. This vision is attained by means of grace, the virtues, and the gifts, in the light of revelation and reason".[9] Theologian Emil Brunner makes it a point to differentiate Christian ethics from the broader topic of philosophical ethics: the broad topic of ethics is about principles of right and wrong conduct, but Brunner says the Christian conception of 'good' differs because it cannot be defined by principles alone. That would be a kind of legalism that is contrary to Christian ethics.[10]:82 According to Brunner, the specific element in Christian ethics that sets it apart is the belief that good human conduct arises out of interaction with the grace of God.[10]:85 This includes morality that arises from natural law and human nature.[4]:11–12

According to Pinckaers, the sources of Christian ethics are the "Scriptures, the Holy Spirit, the Gospel law, and natural law".[11]:xxi, xiii In the Wesleyan tradition, the four sources are scripture, tradition, reason, and Christian experience.[12] Christian ethics is dependent upon the Bible which provides patterns of moral reasoning that focus on conduct and character in what is sometimes referred to as virtue ethics. The Bible is not a work of philosophy or theology, though it contains some of both in informal ancient folk forms.[13]:9;11 Christian ethics has also had a "sometimes intimate, sometimes uneasy" relationship with Greek and Roman philosophy taking some aspects of its basic principles from Plato, Aristotle and other earlier philosophers.[14]:16

Historical background[edit]

Early Christianity[edit]

Christian ethics began its development during the period of Early Christianity which is generally thought to have begun with the ministry of Jesus (c. 27-30) and ended with the First Council of Nicaea (325).[15][16]:51 It emerged out of the heritage shared by both Judaism and Christianity, and depended upon the Hebrew canon as well as important legacies from Greek and Hellenistic philosophy.[14]:1,16 The Council of Jerusalem, as reported in Acts 15, may have been held in Jerusalem about 50AD. Its decree, known as the Apostolic Decree, to abstain from blood, sexual immorality, meat sacrificed to idols, and the meat of strangled animals, was held as generally binding for several centuries and is still observed today by the Greek Orthodox church.[17] Early Christian writings give evidence of the hostile social setting in the Roman empire as Christian ethics sought "moral instruction on specific problems and practices".[14]:2,24 These were not sophisticated ethical analyses, but were instead the practical application of the teachings and example of Jesus to confront specific issues.[14]:24 After Christianity became legal in the fourth century, the range and sophistication of Christian ethics expanded. Through such figures as Augustine of Hippo, Christian ethical teachings had a defining influence upon Christian thought that lasted for several centuries.[15]:774 For example, Augustine's ethic regarding the Jews meant that, "with the marked exception of Visigothic Spain in the seventh century, Jews in Latin Christendom lived relatively peacefully with their Christian neighbors through most of the Middle Ages" until around the 1200s.[18]:xii[19]:3

Middle ages[edit]

In the centuries following the fall of the Roman empire, practices of penance and repentance, using books known as penitentials were carried by monks on their missionary journeys thereby spreading the ethic.[16]:52–56,57 In the middle ages there are "7 capital sins... 7 works of mercy, 7 sacraments, 7 principle virtues, 7 gifts of the Spirit, 8 beatitudes, 10 commandments, 12 articles of faith and 12 fruits of faith".[20]:287 The medieval and renaissance periods saw a number of models of sin listing the seven deadly sins and the virtues opposed to each. The crusades were products of the renewed spirituality of the central Middle Ages when the ethic of living the Apostolic life and chivalry began to form.[21]:177[22]:130–132

Inaccurate Latin translations of classical writings were replaced in the twelfth century with more accurate ones. This led to an intellectual revolution called scholasticism, which was an effort to harmonize Aristotelian and Christian thought.[23]:220,221 In response, Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) wrote "one of the outstanding achievements of the High Middle Ages", the Summa Theologica, that became known as Thomism, containing many ethics that continue to be used.[23]:222

By the 1200s, both civil and canon law had become such a major aspect of ecclesiastical culture that law began dominating Christian ethics.[24]:382 Most bishops and Popes were trained lawyers rather than theologians.[24]:382 The legal regulations of the church, and "divine moral law", became confounded, and the moral principle was "lowered to the level of jural legislation".[20]:286 "This mixing of the ethical and the juridicial was communicated to the whole thinking of the age".[20]:292

Reformation, Counter Reformation and Christian humanism[edit]

Luther, in his classic treatise On Christian Liberty argued that moral effort is a response to grace: humans are not made good by the things they do, but if they are made good by God's love, they will be impelled to do good things.[14]:111 John Calvin adopted and systematized Luther's main ideas grounding everything in the sovereignty of God.[14]:120 In Calvin's view, all humans have a vocation, a calling, and the guiding measure of its value is simply whether it impedes or furthers God's will. This gives a 'sacredness' to the most mundane and ordinary of actions leading to the development of the Protestant work ethic.[14]:116–122 Calvin upheld the separation of the spiritual and earthly roles for government, asserting that one important role of civil government is to provide restraint for evildoers.[14]:122,123 Thus, Calvin also supported just war in opposition to the pacifism of the Anabaptists of his time.[14]:124 The Reform ethic contributed to ideas of popular sovereignty asserting human beings are not "subjects of the state but are members of the state".[14]:125 During the Reformation, Protestant Christians pioneered the ethics of religious toleration and religious freedom.[25]:3

Max Weber asserted that there is a correlation between the ethics of the Reformers and the predominantly Protestant countries where modern capitalism and modern democracy developed first.[14]:124[26] The secular ideologies of the Enlightenment followed shortly on the heels of the Reformation, but "it is a nice question whether those (Enlightenment) ideas would have been as successful in the absence of the Reformation, or even whether they would have taken the same form".[14]:125

The Roman Catholic church of the 1600s responded to Reformation Protestantism in three ways.[23]:335 Papal reform began with Pope Paul III (1534 - 1549). New monastic orders grew with the most influential being the Society of Jesus commonly known as the Jesuits.[23]:336 The Jesuits commitment to education put them at the forefront of many colonial missions.[23]:336 The third response was by the Council of Trent in 1545 and 1563. The Council asserted that the Bible and church tradition were the foundations of church authority, not just the Bible as Protestants asserted; the Vulgate was the only official Bible and other versions were rejected; salvation was through faith and works, not faith alone; and the seven sacraments were reaffirmed. "The moral, doctrinal and disciplinary results of the Council of Trent laid the foundations for Roman Catholic policies and thought right up to the present".[23]:337

Christian humanism taught that any Christian with a "pure and humble heart could pray directly to God" without the intervention of a priest.[23]:338 They believed that imitating the early church would revitalize Christianity and restore its original purpose. "The outstanding figure among the northern humanists — and possibly the outstanding figure among all humanists — is the Dutch scholar Desiderius Erasmus".[23]:338 His ethical views included advocating for education in the humanities, "emphasizing the study of Classics, and honoring the dignity of the individual. He promoted the philosophy of Christ as expressed in the Sermon on the Mount and in living a humble and virtuous life".[23]:339

Modern Christian ethics[edit]

Christian ethics separated from theology in the Enlightenment era.[3]:41 The authority of the Bible, faith and religion itself were challenged by pietism and rationalism.[27]:465 This eventually led to the post-modern view that no appeal to authority can be accepted as sufficient to establish truth.[3]:ix The primary concern of the early modern period was the nature of human nature. This included discussion of where moral authority comes from and what defines human responsibility, free will, the nature of the self, and moral character. "Beginning with the rise of Christian social theory" in the nineteenth century, Christian ethics became heavily oriented toward discussion of nature and society, wealth, work, and human equality.[27]:511–512 In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, "the appeal to inner experience, the renewed interest in human nature, and the influence of social conditions upon ethical reflection introduced new directions to Christian ethics".[27]:511–512

Multiple versions of modern Christian ethics were produced by the influence of different strands of thought. The Social gospel attempted to respond to the effects of modern industrialization.[3]:41 Immanuel Kant grounded morality in nature, independent of theology.[3]:41 Stanley Hauerwas asserts that modern ethics, along with theology itself, both accepted and accommodated that Kantian separation, thereby making both ethics and theology "impoverished".[3]:42 In the twenty-first century, this has often resulted in Christian ethics on one side of a discussion and secularism on the other, with Christian ethics fighting for relevancy.[3]:2 William J. Meyer asserts the answer to this difficulty lies in embracing secular standards of rationality and coherence while refusing secular conclusions.[3]:5 James M. Gustafson also asserts that modern ethics must be grounded in natural law, as secular morality is, while addressing both theology and ethics in "an integrative process" that is careful to consider circumstances, method, and procedures for decision making, while it also "gathers relevant information and knowledge from the social and natural sciences".[8]:xvi The "struggle to embrace modernity without abandoning faith ... is arguably the critical fault line in the contemporary world".[3]:5

John Carman says the central question of Christian ethics is, and has always been, how the Christian and the church relates to the surrounding social and political world.[27]:463 "This has led to the development of three distinct types of modern Christian ethics: the church, sect and mystical types".[27]:463 In the church type of Roman Catholicism and mainstream Protestantism, the Christian ethic is lived within the world, in marriage, family, and work, while living within and participating in municipal counties, cities and nations. This ethic is meant to permeate every area of life. The ethic of the sect works in the opposite direction. It is practiced by withdrawing from the world, minimizing interaction with it while living outside or above the world in communities separated from other municipalities. The mystical type advocates an ethic that is purely an inward experience of personal piety and spirituality. It often includes asceticism.[3]:465 In the last century and a half, a fourth formulation of the Christian ethic as social reform has also developed. There is also geographic diversity in modern Christian ethics.[27]:464

Philosophical core[edit]

Gustafson sets out four basic points any theologically grounded ethic must address: (a) (metaphysics) God, his will, and his relation to the world and humans; (b) (epistemology) how humans know and distinguish justified belief from mere opinion, through human experience, community, nature and man's place in it; (c) (ethics) persons as moral agents; (d) and (applications) how persons ought to make moral choices and judge their own acts, the acts of others and the state of the world.[28]:14

Metaphysical foundations[edit]

The Christian metaphysic is rooted in the biblical metaphysic of God as 'Maker of Heaven and earth'.[4]:25 Modern thought has widely held that metaphysical claims about God cannot be validated.[3]:xi Yet, "to speak of the reality of God is ... to make a metaphysical claim about the ultimate character of existence".[3]:xi Philosopher Mark Smith explains that, in the Bible, a fundamental ontology is embodied in language about power, where the world and its beings derive their reality (their being, their power to exist, and to act) from the power of God (Being itself). The messenger divinities, the angels, derive their power from the One God, as do human kings. In metaphysical language, the power of lesser beings participates in Power itself, which is identified as God.[29]:162

Theology and philosophy professor Jaco Gericke says that metaphysics is found anywhere the Bible has something to say about "the nature of existence, reality, being, substance, mereology, time and space, causality, identity and change, objecthood and relations (e.g. subject and object), essence and accident, properties and functions, necessity and possibility (modality), order, mind and matter, freewill and determinism, and so on."[30]:207 Rolf Knierim says the Bible's metaphysic is "dynamistic ontology" which says reality is a dynamic process.[30]:208

God as 'Maker of Heaven and earth' establishes within this ethical system that whatever is, is good, in its original created form. "The order of being is the order of value".[4]:25 Humanity is the highest level of development in creation, but humans are still creatures. In Christian ethics, the knowledge that human "creatureliness" is shared with all creation is not independent of knowledge of God.[10]:492 In the Christian metaphysic, humans have free will, but it is a relative and restricted freedom.[10]:494

The Christian view of the nature of reality has been called "biblical theism" and "biblical personalism": the belief that "ultimate reality is a personal God who acts, shows and speaks..."[13]:13,17 This view asserts that humans reflect the relational nature of God.[13]:13,17 Some view the mind as the distinctive characteristic of what makes a human, human, while others say the self is a body, and the mind is merely the brain at work. Christian voluntarism points to the will as the core of the self. The Christian ethic says that within human nature, "the core of who we are is defined by what we love" and that this determines the direction of moral action.[4]:25–26

Modern scholars such as James M. Gustafson reject this "personalism" as anthropomorphic: humans reading their humanity onto the nature of God.[28]:16 Gordon D. Kaufman argues that an impersonal understanding of divinity is insufficient to evoke a piety beyond the natural piety humans feel toward the natural order.[28]:36 Both scholars make similar statements to Karl Barth's, that the "notion of the Wholly Other requires a notion of revelation as the only basis on which it may be apprehended".[28]:36

Because humans reflect the nature of ultimate reality in Christian ethics, they are seen as having a basic dignity and value and should be treated, as Kant said, as "an end in themselves" and not as a means to an end.[13]:18 Humans have a capacity for reason and free will which enable making rational choices. They have the natural capacity to distinguish right and wrong which is often called a conscience or natural law. When guided by reason, conscience and grace, humans develop virtues and laws. In Christian metaphysics, "Eternal Law is the transcendent blueprint of the whole order of the universe... Natural Law is the enactment of God's eternal law in the created world and discerned by human reason".[4]:11–12

Epistemology[edit]

Christian ethics asserts that it is possible for humans to know and recognize truth and moral good through the application of both reason and revelation.[4]:23 Observation, reasoned deduction and personal experiences, which includes grace and the experience of language, are the means of that knowledge.[31] "It is arguably one of Judaism's greatest contributions to the history of religions to assert that the divine Reality is communicated to mankind through words".[32]:129

In Christian ethics, "knowing" is built on different assumptions than those of philosophical epistemology: James Gustafson says the Christian ethic assumes either a condition of piety, or at least a longing for piety.[8]:152 This piety is an attitude of respect evoked by "human experiences of dependence upon powers we do not create and cannot fully master".[8]:87 Such piety must be open to a wide variety of human experiences, including "data and theories about the powers that order life which come from many areas of human investigation".[8]:87 It engages the affections, and takes the form of a sense of gratitude.[8]:88 Trust is also seen as an aspect of knowing: underneath science is a trust that there is an identifiable order and discoverable principles beneath the disarray of complex data; this is comparable to the trust of the Christian faith that "there is unity, order, form and meaning in the cosmos ...of divine making".[4]:23–24 "Knowledge conditions are relative to particular communities" and all human knowledge is based on the experiences we have within the culture we live in: all human experience is interpretive.[28]:124

Evidentialism in epistemology, which is advocated by Richard Swinburne (1934–), says a person must have some awareness of evidence for a belief for them to be justified in holding that belief.[33] People hold many beliefs that are difficult to evidentially justify, so some philosophers have adopted a form of reliabilism instead. In reliablilism, a person can be seen as justified in a belief, so long as the belief is produced by a reliable means even when they don't know all the evidence.[33]

Alvin Plantinga (1932–) and Nicholas Wolterstorff (1932–) advocate Reformed epistemology taken from Reformer John Calvin's (1509–1564) teaching that persons are created with a sense of God (sensus divinitatis). Even when this 'sense' is not apparent to the person because of sin, it can still prompt them to believe and live a life of faith. This means belief in God may be seen as a properly basic belief similar to other basic human beliefs such as the belief that other persons exist, and the world exists, just as we believe we exist ourselves. Such a basic belief is a 'warranted' belief even in the absence of evidence.[33]

Paul Moser has systematically argued for volitional epistemology. Moser contends that if the God of Christianity exists, this God would not be evident to persons who are simply curious. This God would only become evident in a process involving moral and spiritual transformation. This process might involve persons accepting Jesus Christ as a redeemer who calls persons to a radical life of loving compassion. "By willfully subjecting oneself to the commanding love of God, a person in this filial relationship with God, through Christ, may experience a change of character (from self-centeredness to serving others) in which the person’s character (or very being) may come to serve as evidence of the truths of faith".[33]

Basic ethical principles[edit]

Every ethical system "presupposes some particular understanding of human nature, its capacities and its needs. Theocentrism is, therefore, an ethical stance as well as a metaphysical one".[28]:15–16 Christian ethics asserts the ontological nature of moral norms from God: that the human is does not necessarily reflect the divine ought, but Christian ethics is also accountable to standards of rationality and coherence and must make its way through both what is ideal and what is possible.[4]:9 Thus some biblical ethics are seen as "more authoritative than others. The spirit, not the letter, of biblical laws becomes normative".[4]:15

According to D. Stephen Long, the Hebrew Bible and the Life of Jesus in the New Testament provide the primary foundations of Christian ethics.[34][35] The diversity of the Bible means that it does not have a single ethical perspective but instead has a variety of perspectives; this has given rise to disagreements over defining the foundational principles of Christian ethics.[14]:2,3,15 For example, reason has been a foundation for Christian ethics alongside revelation from its beginnings, but Christian ethicists have not always agreed upon "the meaning of revelation, the nature of reason and the proper way to employ the two together."[14]:3,5

A minority view advocated by Sam Wells and Ben Quash divides the principles of Christian ethics into three categories: universal, subversive, and ecclesial principles. Universal ethics are defined as ethics for anyone; subversive ethics are ethics for the marginalized of any era; and ecclesial ethics are those specifically for the church.[36]:viii

Good and evil[edit]

Christian ethics assumes the existence of good and evil, but has a particular frame of reference that begins from defining and understanding what is good.[37]:5 As everything begins with God, and God is defined as the ultimate good, the presence of evil and suffering must be adequately accounted for.[2]:219 There are two concepts of evil in philosophy: a broad concept that defines evil as "any bad state of affairs, wrongful action, or character flaw" and includes all suffering as evil, no matter the type, from all natural events and moral actions.[38] The second is the narrow concept of evil. It only involves moral agents and their actions. In this narrow view, not all suffering is a moral evil, just as not all pleasure is a moral good. The Christian ethic does not see all suffering as innately evil because the Christian story "is a story of the salvific value of suffering".[33] Within this view, nature is not a moral agent with the ability to choose, so natural evil has no moral quality.[33]

Augustine is one of the earliest proponents of philosophical theodicy which attempts to reconcile a good god with the reality of evil and suffering.[37]:2 Augustine defines evil as an absence of good. We know if something is good, for example if a watch is a good watch, by referencing its purpose and how well it fulfills it.[37]:45 Things and people become good or evil in their actions based on whether "they succeed or fail in achieving the end for which God supposedly created them".[39]

Augustine asserted that nothing can ever be "absolutely and totally evil in itself". Evil has no ontological nature of its own. It must be attached to something that exists in nature, which by definition of having existence, is a good. The morally depraved may seek to do only evil by misusing the good of their intellect and will, yet the good of their intellect and will remains. Augustine also asserted that pain and suffering can have some good to them if they produce an awareness of, and an aversion to, sin and evil.[40] The peculiar paradox of the human condition is in how much "evil and good, creativity and selfishness, are mixed up in actual life".[37]:181

Inclusivity, exclusivity and pluralism[edit]

There is tension between inclusivity and exclusivity inherent in all the Abrahamic traditions. According to the book of Genesis, Abraham is the recipient of the promise of God to become a great nation. The promise is given to him and his 'seed,' exclusively, yet the promise also includes that he will become a blessing to all nations, inclusively (Genesis 12:3).[41] Paul claims that because the 'seed' is singular, not plural, it refers to Christ, therefore baptized Gentile Christians are inclusively heirs of the promise if they have Abraham's faith even though they are not Jewish.[41] Yet by the second century, Christianity had also defined what it meant to be a Christian exclusively, by separating itself from Judaism and the Judaizers through its definitions of orthodoxy and heterodoxy.[42]:1 The God of the Bible is the inclusive God of all nations and all people, yet there is also "special membership" through baptism in the exclusive community identified with Him.[2]:628 Christians are referred to as the "elect" Romans 8:33 Matthew 24:22 implying God has chosen some and not others for salvation, yet the Great Commission Matthew 28:19 is a command to go to all nations. Christians and non-Christians have, throughout much of history, had significant moral and legal questions concerning this ethical tension.[43]:8 Yet there is no question that Christians pioneered the concept of religious freedom which rests upon an acceptance of the necessity and value of pluralism, a modern day concept often referred to as moral ecology.[25]:3[44]

Law, grace and human rights[edit]

Christian ethics emphasizes morality. The prophets of the Old Testament show God as rejecting all unrighteousness and injustice and commending those who live moral lives. The law and the commandments are set within the context of devotion to God. "God as lawgiver and judge has high moral expectations".[43]:8 This is sometimes offered as a contrast to the New Testament ethic, but this moral ethic is not a contrast; it's a pre-supposition because the Christian ethic is built on its Old Testament base.[43]:8,9 The Christian ethic requires not only the Old Testament rejection of active murder, but also the New Testament awareness of the anger and hatred that lead to it (Matthew 5:21-22).[43]:9 According to Martin Luther, the Christian ethic says those who follow the way of grace are no longer under law but are instead free from the law's power.[14]:111 In traditional Christian ethics, law and its just enforcement is overshadowed by the ethics of grace, mercy and forgiveness as aspects of redemption instead of punishment.[43]:9;116–120 "Part of the biblical legacy of Christian ethics is the necessity somehow to do justice to both sides".[43]:9

Human rights is the language through which the Christian ethic is able to relate these concepts to the world.[45]:310 In a convergence of opinion among Catholics, Lutherans, Reformed, and others, this has led to a support of human rights becoming common to all varieties of Christian ethics.[45]:304 According to Christopher Marshall, there are features of covenant law that have been adapted to contemporary human rights law: due process, fairness in criminal procedures, and equity in the application of law. Within this ethic, judges were told not to accept bribes (Deuteronomy 16:19), were required to be impartial to native and stranger alike (Leviticus 24:22; Deuteronomy 27:19), to the needy and the powerful alike (Leviticus 19:15), and to rich and poor alike (Deuteronomy 1:16,17; Exodus 23:2–6). The right to a fair trial, and fair punishment, are also required (Deuteronomy 19:15; Exodus 21:23–25). Those most vulnerable in a patriarchal society—children, women and strangers—were singled out for special protection (Psalm 72:2,4).[46]:47–48 In natural law, "...human rights is what is meant by morality".[45]:304

Authority, force and personal conscience[edit]

Christian ethics asserts that "love is, and must remain", its foundation.[43]:331 Individuals are commanded to "turn the other cheek" Matthew 5:38-39, "love your enemies" Matthew 5:43-45, "bless those who persecute you" Romans 12:14-21 and more, as matters of personal conscience that define the very nature of being a Christian.[43]:330 Yet, "justice, as the institutional structure of love, is inevitably dependent upon other incentives, including, ultimately the use of force".[43]:331 The state's ability to create peace and order is in its ability to use force against those who create chaos, disorder and harm to others.[10]:469 Both the Old and the New Testaments contain explicit commands to respect authority. Traditional Christian ethics has tended to support respect for authority even when the ruler is unjust.[43]:123 Christian ethics is, and always has been, divided over the interplay of justice, power and personal responsibility.[10]:469

Self-affirmation and self-denial[edit]

According to the book of Genesis, God created and declared creation, including humans, good (Genesis 1:31). The Song of Songs depicts sensual love as good. Other parts of the Old Testament depict material prosperity as a reward. Yet, the New Testament references the life of the Spirit as the ultimate goal, and warns against worldliness.[43]:7 In the traditional view, this requires self-sacrifice, self-denial and self-discipline, and greatness lies in being a servant to all (Mark 10:42-45).[43]:7 Martin Luther wrote that an "authentic response to God's grace means a life of service" to others.[4]:14

Yet according to ethicist Darlene Weaver, the traditional Christian ethic that undergirds this life of service mixes together self-love and pride as if they were the same things. From the nineteenth century on, this produced a definition of self-love that excluded those whose sin is self-abnegation, rather than prideful self-assertion, allowing those in power to oppress minorities.[47]:62,64 Weaver claims "there is no ontological split between self/other; there is no monolithic polarity of self-interested action versus other-regardingness. All people - each of us-in-relation-to-all - have a mandate rooted in God to the sort of self-assertion that grounds and confirms our dignity in relationship".[47]:64 Josh McDowell asserts that a biblical self love is not a narcissistic love. It reflects that humans are loved because God made them, and they reflect his image. Self love is the basis for loving others since the command is not to love others instead of yourself, but as yourself. The Christian ethic teaches that God first loved humans, and so all humans are called to love others and themselves as well.[48]

Wealth and poverty[edit]

There are a variety of Christian views on poverty and wealth. At one end of the spectrum is a view which casts wealth and materialism as an evil to be avoided and even combatted. At the other end is a view which casts prosperity and well-being as a blessing from God. Some Christians argue that a proper understanding of Christian teachings on wealth and poverty needs to take a larger view where the accumulation of wealth is not the central focus of one's life but rather a resource to foster the "good life".[49] Professor David W. Miller has constructed a three-part rubric which presents three prevalent attitudes among Protestants towards wealth: that wealth is (1) an offense to the Christian faith (2) an obstacle to faith and (3) the outcome of faith.[50]

The Christian ethic is not an opponent of poverty since Jesus embraced it, but it is an opponent of the destitution that results from social injustice.[51]:25 Kevin Hargaden says "No Christian ethic can offer a consistent defense of massive wealth inequality".[51]:77 Prophets like Amos (Amos 8:4,6) and Micah (Micah 2:2) are deeply offended by the indifference of the rich to the plights of the poor. Levitical laws made provision for the poor, the prompt payment of wages, forgiveness of debts and redemption of the enslaved.[43]:7

Jesus engaged with concepts concerning money, profit and wealth extensively in a complex ethic that "appears (at best) ambivalent to the holding of riches. This puts Western Christians, who typically enjoy a material standard of life the like of which is unequalled in human history, in a precarious position".[51]:xv When Jesus depicts wealth as a "master, or a Lord, or an idol", he is describing the corrosive power of Mammon, and loyalties and desires that run much deeper than ordinary fiscal practices.[51]:xvi American theologian John B. Cobb has argued that the "economism that rules the West and through it much of the East" is directly opposed to traditional Christian doctrine. Cobb invokes the teaching of Jesus that "man cannot serve both God and Mammon (wealth)". He asserts that it is obvious that "Western society is organized in the service of wealth" and thus wealth has triumphed over God in the West.[52] We now live in societies with no concept of an "acquisitive ceiling".[51]:26

Gender and sexuality[edit]

Lisa Sowle Cahill calls sex and gender one of the most difficult topics in new studies of Christian ethics. As "the rigidity and stringency of [sic] traditional moral representation has collided head-on with historicized or "postmodern" interpretations of moral systems" tradition has acquired a new form of patriarchy, sexism, homophobia and hypocrisy.[53]:xi Feminist critics have suggested that part of what drives traditional sexual morality is the social control of women, yet within postmodern western societies the "attempt to reclaim moral autonomy through sexual freedom" has produced a loss of all sense of sexual boundaries.[53]:75;xi "Personal autonomy and mutual consent are almost the only criteria now commonly accepted in governing our sexual behavior".[53]:1

Christian ethics is, by its nature, a transformative ethic of discipleship with profound implications for moral relationship.[53]:257;122 The gospel requires that all relationships be reconfigured by new life within the community, yet the New Testament has no systematic investigation into all facets of any moral topic, no definitive guidance for the many variations of moral problems that exist in the twenty-first century. [53]:121 Instead, New Testament authors challenge that which perpetuates sin, and encourage the transformation that embodies the reign of God.[53]:122

Areas of applied ethics[edit]

Politics[edit]

There is no political theory, as such, in the Bible, however, the political views that are found there are comparable to modern "consent theory" which requires agreement between the governed and the governing authority; and to "social contract theory" which says a person's moral obligations to form the society in which they live are dependent on the agreement they made.[54]:xii Moral law is politically democratized in the Bible, and is similar to later "general will" theories of democracy.[54]:7–15;200 In this biblical view, everyone was seen as equally subject to God's law — kings were as subject to it, in principle, as every other Israelite, yet kings were not involved in making or interpreting law. That was left to the Levites and priests. The power of politics was thereby kept separate from the power of religion. In the Bible, prophets speak as interpreters of divine law in public places, to those at the top of society as well as those at the bottom, demonstrating another important aspect of democracy.[54]:200–201

The political ethic of the Reformation built on these concepts, contributing to ideas of popular sovereignty by asserting that human beings are not "subjects of the state but are members of the state".[14]:125 John Calvin's Institutes contains a discussion of civil government that distinguishes between the civil and the spiritual. He insists on a place for civil government in the divine order, saying those who don't agree have forgotten "the depth of human evil" and the need to restrain it, which he sees as the main purpose of civil government.[43]:122

Christian involvement in politics is both supported and opposed by Christian ethics.[55] Political science scholar Amy E. Black says Jesus' command to pay taxes (Matthew 22:21), was not simply an endorsement of government, but was also a refusal to participate in the fierce political debate of his day over the Poll tax. As Gordon Wenham says: Jesus' response "implied loyalty to a pagan government was not incompatible with loyalty to God."[56]:7

War and peace[edit]

The Christian ethic addresses warfare with views that support pacifism, non-resistance, just war, and preventive war which is sometimes called crusade.[57]:13–37[58]:5 :159 In all four views, the Christian ethic presumes war is immoral and must not be waged or supported by Christians until certain conditions have been met that enable the setting aside of that presumption.[14]:336

According to theologian Myron S. Augsberger, pacifism opposes war for any reason. The ethic is founded in separation from the world and the world's ways of doing things, obeying God first rather than the state, and belief that God's kingdom is beyond this world. Most texts used to support pacifism are in the New Testament, such as Matthew 5:38–48 and Luke 6:27–36.[59]:81–83 Pacifism is not in the Old Testament, though an ethic of peace can be found there.[60]:278 The peace passages, such as Micah 4:3: "They will beat their swords into plowshares and their spears into pruning hooks", are sometimes cited in support of pacifism.[59]:81–97[61]:83

In the first few centuries of Christianity, most Christians refused to engage in military combat, and some scholars claim this was from pacifist motives.[62][63] The rejection of military service is attributed by Professor of theology Mark J. Allman to two motivations: "(1) the use of force (violence) was seen as antithetical to Jesus' teachings and (2) service in the Roman military required worship of the emperor as a god which was a form of idolatry."[64] Bible scholar Herman A. Hoyt says Christians are obligated to follow Christ's example, which was an example of non-resistance rather than pacifism.[65]:32,33

Both pacifism and non-resistance are interpreted in the Christian ethic as applying to individual believers, not corporate bodies, or "unregenerate worldly governments."[65]:36

Just war requires that war be waged as self-defense or the defense of others.[66]:115–135 Levin and Shapira say forbidding war for the purpose of expansion (Deuteronomy 2:2-6,9,17-19), the call to talk peace before war (Deuteronomy 20:10), the expectation of moral disobedience to a corrupt leader (Genesis 18:23-33;Exodus 1:17, 2:11-14, 32:32;1 Samuel 22:17), as well as a series of verses governing treatment of prisoners (Deuteronomy 21:10–14; 2 Chronicles 28:10–15; Joshua 8:29, 10:26–27), respect for the land (Deuteronomy 20:19), and general "purity in the camp" (Deuteronomy 20:10–15) are all aspects of the principles of just war in the Bible.[67]:270–274

The earliest biblical sources show there are two ethics of conquest in the Bible with laws supporting each.[54]:36–43 Beginning at Deuteronomy 20:10–14[68] there is a limited war/just war doctrine consistent with Amos and First and Second Kings. In Exodus, Deuteronomy, Joshua, and both books of Kings, warfare also includes narratives where God commands the Israelites to conquer the Promised Land, placing city after city "under the ban": the herem of total war.[69] This has been interpreted to mean every man, woman and child was to be killed.[70]:92–108 This leads many contemporary scholars to characterize herem as a command to commit genocide.[71]:242 Herem was the common approach to war among the nations surrounding Israel of the Bronze age, and Hebrew scholar Baruch A. Levine indicates Israel imported the concept from them.[72] This method of war was a political response necessary for survival of a nation of that era and not a religious ethic to be carried forward to other times.[73]:33 [74]:10–11 Starting in Joshua 9, (after the conquest of Ai), Israel's battles are described as self-defense, and the priestly authors of Leviticus, and the Deuteronomists, are careful to give God moral reasons for his commandment.[75][54]:7

Holy war imagery is contained in the final book of the New Testament, Revelation, where John reconfigures traditional Jewish eschatology by substituting "faithful witness to the point of martyrdom for armed violence as the means of victory. Because the Lamb has won the decisive victory over evil by this means, his followers can participate in his victory only by following his path of suffering witness. Thus, Revelation repudiates apocalyptic militarism, but promotes the active participation of Christians in the divine conflict with evil".[76]

The last 200 years have seen a shift in moral focus concerning the state's use of force.[77]:59 Justification for war in the twenty-first century has become the ethic of intervention and humanitarian goals of protecting the innocent, thereby altering the modern purpose and character of military force.[78]

Criminal justice[edit]

Key elements in criminal justice begin with the idea that God is the ultimate source of justice, and the judge of all, including those administering justice on earth.[79] Ethical knowledge and the moral character of those within a justice system are seen as central to the administration of justice with principles prohibiting "lying and deception, racial prejudice and racial discrimination, egoism and the abuse of authority" foremost.[80]:xx

Ethical views on the meaning of justice help determine the nature of a society's criminal justice system. Aristotle's classic definition of justice, giving each their due, entered into Christian ethics through scholasticism and Thomas Aquinas. For Aristotle and Aquinas that meant a hierarchical society with each receiving what was due according to their social status. This allows for the criminal justice system to be retributive, and fails to recognize a concept of universal human rights and responsibilities. After Aquinas, the social gospel redefined getting one's due as: "from each according to his ability, to each according to his need". Along these lines, justice had an egalitarian form while retaining male domination. Similarly, justice for slaves was defined as paternalistic care.[14]:325 "We can expect such issues to continue to occupy Christian ethics for years to come".[14]:325

Capital punishment[edit]

Biblical ethicist Christopher Marshall says there are about 20 offenses that carry the death penalty in the Old Testament.[46]:46 Within the historical and ethical context of covenant, it was believed the covenant community suffered ritual pollution from certain sins, therefore capital punishment protected the community from the possible consequences of such pollution, as well as punished those who had broken covenant.[46]:47 "Evans explains that contemporary standards tend to view these laws of capital punishment as cavalier toward human life", however, within the framework of ancient covenant, it suggests an ethic concerning the value of life was as much a communal value as an individual one.[46]:46–47

In Christian ethics of the twenty-first century, capital punishment has become controversial, and there are Christian ethicists on both sides. Abolitionists have sometimes elevated the condemned into an oppressed brotherhood, but John P. Conrad asserts that those on death Row have indeed committed terrible crimes for which they seldom expressed regret and a few even took pride in.[81]:9 This reality, and the danger they present to society, must be acknowledged, but the argument against capital punishment is not based on what the criminal might be seen to deserve. The argument against retribution is simple: killing is wrong; it is simply not a permissible act, even for the state.[81]:10 On the other hand, contemporary society acknowledges the need for rewards and punishments; order is established by the state's ability to enforce its requirements.[81]:18 Capital punishment can be seen as respect for the worth of the victim by calling for the equal cost to the offender, and respect for the offender as well, by treating them as free agents, responsible for their own choices, who must bear the responsibility for their acts just as any citizen must.[82]

Relationships[edit]

In most ancient religions the primary focus is on human kind's relationship to nature, whereas in the Christian ethic, the primary focus is on the relationship with God as the "absolute moral personality".[20]:23 The distinguishing character of the Old Testament ethic of ancient Israel is that its "history as a people is the bearer and form of the relationship of salvation between God and mankind, and of the historical realization of that relationship".[20]:34 Exodus and Deuteronomy frame the encounter between God and man in terms of covenant: a mutual agreement. The people enter voluntarily into relationship with God: because He chooses them, they choose Him. Law, and ethics, then, are also chosen and not imposed.[83] The Christian ethic rises out of this context.[84]

Neighbors[edit]

Traditional Christian ethics recognizes the command to "love thy neighbor" as one of the two primary commands called the "greatest commands" by Jesus.[85]:24 This is a principle that reflects an attitude toward others rooted in "beliefs about God's character, activity and will and about our nature as participants in that will".[85]:53,54 It aims at promoting another person's good in an "enlightened unselfishness".[84]:175 When the Pharisee asked Jesus: "Who is my neighbor?", Stanley J. Grenz says the questioner intended to limit the circle of those to whom this obligation was due, but Jesus responded by reversing the direction of the question into "To whom can I be a neighbor?".[84]:107 In the parable of the "Good Samaritan", the use of a racially despised and religiously rejected individual as an example of the good, defines neighbor as anyone in need that one comes across.[86] The full thought in Mark 12:31 is to love others as one loves oneself, and Christian ethics has not traditionally supported self-love as a good, but according to Koji Yoshino, "altruistic love and self-love are not contradictory to each other. Those who don't love themselves cannot love others, nevertheless, those who ignore others cannot love themselves".[87]

Women[edit]

Jesus held women personally responsible for their own behavior: the woman at the well (John 4:16–18), the woman taken in adultery (John 8:10–11), and the sinful woman who anointed his feet (Luke 7:44–50), are all dealt with as having the personal freedom, and enough self-determination, to choose their own repentance and forgiveness. New Testament scholar Ben Witherington III says "Jesus broke with both biblical and rabbinic traditions that restricted women's roles in religious practices, and He rejected attempts to devalue the worth of a woman, or her word of witness."[88]:127

The New Testament names many women among the followers of Jesus and in positions of leadership in the early church.[89][90] New Testament scholar Linda Belleville says "virtually every leadership role that names a man also names a woman. In fact there are more women named as leaders in the New Testament than men. The only role lacking specific female names is that of 'elder'—but male names are lacking as well."[91]:54,112

Women in the church were ordained up until the 1200s.[92]:30 Before the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, ordination was dedication to a particular role or ministry. When theologians of this medieval period circumscribed the seven sacraments, they changed the vocabulary and gave the sacrament exclusively to male priests.[92]:30 In the nineteenth century, rights for women brought a wide variety of responses from Christian ethics with the Bible featuring prominently on both sides ranging from traditional to feminist.[93]:203 In the late twentieth century, the ordination of women became a controversial issue. Linda Woodhead states that, "Of the many threats that Christianity has to face in modern times, gender equality is one of the most serious".[94]

The four primary views of Christian ethics on the roles of women include Christian feminism, which defines itself as a school of Christian theology which seeks to advance and understand the equality of men and women;[95] Christian egalitarianism argues that the Bible supports "mutual submission" without requiring a hierarchy of authority.[96] Complementarianism sees women as 'Ontologically equal, Functionally different'.[97] Biblical patriarchy asserts 1 Corinthians 14:34-35, 1 Timothy 2:11–15, and 1 Corinthians 11:2–16 in a literal hierarchical manner as part of an inerrant biblical authority.[98][91]:97

Marriage and divorce[edit]

Among the early church fathers, married life was treated with some sensitivity as a relationship of love and trust and mutual service, contrasting it with non-Christian marriage as one where passions rule a "domineering husband and a lusty wife".[93]:24 In the synoptic Gospels, Jesus is seen as emphasizing the permanence of marriage, as well as its integrity: "Because of your hardness of heart, Moses allowed you to divorce your wives, but from the beginning it was not so".[99][100] Restriction on divorce was based on the necessity of protecting the woman and her position in society, not necessarily in a religious context, but in an economic context.[101] Paul concurred but added an exception for abandonment by an unbelieving spouse.[102]:351–354

Augustine wrote his treatise on divorce and marriage, De adulterinis coniuigiis, in which he asserts couples may only divorce on the ground of fornication (adultery) in 419/21, even though marriage didn't become one of the seven sacraments of the church until the thirteenth century.[102]:xxv Though Augustine confesses in later works (Retractationes) that these issues were complicated and that he felt he had failed to address them completely, adultery was the standard necessary for legal divorce until the modern day.[102]:110 The twenty-first century Catholic Church still prohibits divorce, but permits annulment (a finding that the marriage was never valid) under a narrow set of circumstances. The Eastern Orthodox Church permits divorce and remarriage in church in certain circumstances.[103] Most Protestant churches discourage divorce except as a last resort but do not actually prohibit it through church doctrine, often providing divorce recovery programs as well.[104][105]

Sexuality[edit]

Kyle Harper says ethics concerning sexuality was at the heart of Christianity's early clash with its surrounding pagan culture. The sexual-ethical structures of Roman society were built on status, and sexual modesty and shame were social concepts that were always mediated by gender and status.[106] :10,38[107][108]:7 Views on sexuality in the early church were diverse and fiercely debated within its various communities; these doctrinal debates took place within the boundaries of the ideas in Paul's letters, and in the context of an often persecuted minority seeking to define itself from the world around it. In his letters, Paul often attempted to find a middle way among these disputes, which included people who saw the gospel as liberating them from all moral boundaries, and those who took very strict moral stances.[108]:1–14,84–86,88

"The model of normative sexual behavior that developed out of Paul's reactions to the erotic culture surrounding him...was a distinct alternative to the social order of the Roman empire."[108]:85 For Paul, "the body was a consecrated space, a point of mediation between the individual and the divine."[108]:88–92 The ethical obligation for sexual self-control was placed equally on all people in the Christian communities, men or women, slave or free. In Paul's letters, porneia, (a single name for an array of sexual behaviors outside marital intercourse), became a central defining concept of sexual morality, and shunning it, a key sign of choosing to follow Jesus. Sexual morality could be shown by practicing chastity, which Paul defined as remaining virgin or having sex only within a marriage.[108]:88–92 Harper indicates this was a transformation in the deep logic of sexual morality as personal rather than social, spiritual rather than merely physical, and for everyone rather than solely for those with status.[108]:6,7

While Jesus made reference to some that have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven,[109] there is no commandment in the New Testament that Jesus' disciples have to live in celibacy.[100] During the first three or four centuries, no law was promulgated prohibiting clerical marriage. Celibacy was a matter of choice for bishops, priests, and deacons.[100] In the twenty-first century, the Roman Catholic Church teachings on celibacy uphold it for monastics and priests.[110]

Protestantism has rejected the requirement of celibacy for pastors. Celibacy is primarily refraining from premarital sex until the joys of a future marriage. Some evangelicals, particularly older singles, desire a positive message of celibacy that moves beyond the "wait until marriage" message of abstinence campaigns. They seek a new understanding of celibacy that is focused on God rather than a future marriage or a lifelong vow to the Church.[111]

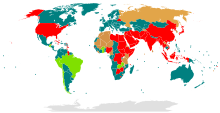

"Today, an uneasiness about sex continues to linger as a heritage from those early Christian efforts to cope with the sexual impulse".[112] In contemporary Christian ethics, there are a variety of views on the issues of sexual orientation and homosexuality. The many Christian denominations vary from condemning homosexual acts as sinful, to being divided on the issue, and to seeing it as morally acceptable. Even within a denomination, individuals and groups may hold different views. Further, not all members of a denomination necessarily support their church's views on homosexuality.[113] "Traditional societies place sex and gender in the context of community, family and parenthood; modern societies respect reciprocity, intimacy and gender equality".[53]:257

Slavery[edit]

Slavery was harsh and inflexible in the first century, and slaves were vulnerable to abuse, yet neither Jesus nor Paul order the abolition of slavery.[114] In the first century, the Christian view was that morals were a matter of obedience to the ordained hierarchy of God and men. The Enlightenment invented the idea that morals were a matter of personal autonomy, and it is an error to interpret first century writings from that later perspective.[115]:296 Paul was opposed to the political and social order of the age in which he lived, but his letters offer no plan for reform beyond working toward the apocalyptic return of Christ. He did indirectly articulate a social ideal through the Pauline virtues, and indirectly attacked the mistreatment of women, children and slaves through his teachings on marriage and his lifestyle. Paul's refusal to marry and set up a household that would require slaves, and his insistence on being self-supporting, was a model followed by many that "structurally attacked slavery by attacking its social basis, the household, and its continuity through inheritance from master to master".[115]:308–309

Saint Augustine described slavery as against God's intention and resulting from sin, saying that, because slaves are people, they are "not on the same plane as other pieces of property".[116] By the early 4th century, Roman law, such as the Novella 142 of Justinian, gave bishops (and priests) the power to free slaves by a ritual performed by that Christian bishop or a priest in a church. It is not known if baptism was required before this ritual.[117] Several early figures, such as Saint Patrick (415-493), Acacius of Amida (400-425), and Ambrose (337 – 397 AD) while not openly advocating abolition, made sacrifices to emancipate or free slaves.[118] Gregory of Nyssa (c. 335-394) went even further and stated opposition to all slavery as a practice.[119][120] Later Saint Eligius (588-650) used his vast wealth to purchase British and Saxon slaves in groups of 50 and 100 in order to set them free.[121]

By the time of Charlemagne, while Muslims were coming onto the scene "as major players in a large-scale slave trade", slavery became almost non-existent in the West till the end of the central middle ages.[122]:38;167 Criticism of the trade in Christian slaves was not new, but at this time, opposition began to get wider support, seeing all those involved in the trade as "symbols of barbarity".[122]:39 Slavery in Africa existed for six centuries before the arrival of the Portuguese and the opening of the Atlantic slave trade.[123]:8 Economics drove it on from there, but the trade was abolished in the U.S. while it was still profitable and important to the American economy.[123]:188 Early abolitionist literature viewed the abolition of slavery as a moral crusade.[123]:188

In modern times, Christian organizations reject slavery, but historically Christian views have varied embracing both support and opposition.[124][125][126][127]

Bioethics[edit]

Bioethics is the study of the life and health issues raised by modern technology that attempts to discover "normative guidelines built on sound moral foundations".[128]:vii This is necessary because the moral questions surrounding new medical technologies have become complex, important and difficult.[129]:9;11 With the tremendous benefits of medical advances, have come the "eerie forebodings of a future that is less humane, not more".[129]:12 Charges of abuses of technology in neo-natal intensive care units have already been leveled.[128]:93,94 Remedies for infertility enable researchers to create embryos as a disposable resource for stem cells. Manipulating the genetic code can prevent inheritable diseases and also produce, for those rich enough, designer babies "destined to be taller, faster and smarter than their classmates".[129]:12 Scripture offers no direct instruction for when a right to life becomes a right to death.[129]:14

The Catholic bioethic can be seen as one that rests on natural law. Moral decision making affirms the basic "goods" or values of life, which is built on the concept of a hierarchy of values, with some values more basic than others.[128]:20,17 For example, Catholic ethics supports self-determination but with limits from other values, say, if a patient chose a course of action that would no longer be in their best interests, then outside intervention would be morally acceptable.[128]:18 If there is conflict over how to apply conflicting values, then a proportionate reasoned decision which includes values such as preservation of life, human freedom, and lessening pain and suffering must be made by recognizing that not all values can be realized in these situations.[128]:19–20

The Protestant Christian ethic is rooted in the belief that agape love is its central value, and that this love is rooted in covenant fidelity expressed in pursuit of good for other persons.[128]:20–22 This ethic as a social policy may use natural law and other sources of knowledge, but in the Protestant Christian ethic, apape love must remain the controlling virtue that guides principles and practices.[128]:23 This Christian ethic determines the moral choice by what is the most love-embodying action within a situation. Actions that can be seen as unconditionally wrong, when they are acts of maximal love toward another, become unconditionally right.[128]:24

Genetic engineering[edit]

New technologies of prenatal testing, DNA therapy and other genetic engineering help many yet also offer ways in which "science and technology can become instruments of human oppression".[14]:303 Prenatal genetic testing has enabled couples to see the genetic make-up of their unborn children, "and in many cases they make decisions to end their pregnancies on the basis of such information".[128]:92 Genetic technologies can correct genetic defects, but the problem is that how one defines defect is often subjective. A short person might consider their height a defect. Parents might have certain expectations for IQ, or hair and eye color, and consider anything else as defective.[128]:118–120 Research into the gene for homosexuality could lead to prenatal tests that predict it, which could be particularly problematic in countries where homosexuals are considered defective and have no legal protection.[130] Such intervention is problematic morally, and has been characterized as "playing God".[128]:93,94

The general view of genetic engineering by Christian ethicists is stated by theologian John Feinburg. He reasons that since diseases are the result of sin coming into the world, and because Christian ethics asserts that Jesus himself began the process of conquering sin and evil through his healings and resurrection, "if there is a condition in a human being (whether physical or psychological) [understood as disease], and if there is something that genetic technology could do to address that problem, then use of this technology would be acceptable. In effect, we would be using this technology to fight sin and its consequences".[128]:120

Abortion[edit]

"If one says that the central issue between conservatives and liberals in the abortion question is whether the fetus is a person, it is clear that the dispute may be either about what properties a thing must have in order to be a person, in order to have the right to life - a moral question - or about whether a fetus at a given stage of development... possesses the properties in question".[45]:50 Most philosophers have picked out the capacity for rationality, autonomy and self-awareness to describe personhood, but there are at least four possible definitions: in order to be a true person, a subject must have interests; possess rationality; be capable of action; and/or possess self-consciousness.[45]:53 A fetus possesses none of these, and so it can be said the fetus is not a true person; the argument can then be moved on to justify infanticide as well. "Without assuming the Christian moral framework" concerning the sanctity of life, "the grounds for not killing persons do not apply to newborn infants. Neither classical utilitarianism nor preferential utilitarianism ... offer good reasons why infanticide should necessarily be wrong".[45]:44–46

In Christian ethics, the reasons for aborting a fetus are what make the difference morally. The Christian narrative includes the child in God's family, takes into account the entire context surrounding its birth, including the other lives involved, and seeks harmony with God's redeeming activity through Christ. It includes confidence in God's ability to sustain and direct those who put their trust in him.[45]:339 Some couples use prenatal testing to determine the gender of their child, and will terminate if the child is not the desired gender. This is more common in the Third world where "women have far fewer rights and female children are viewed as liabilities with bleak futures. In some of those countries, genetic testing is widely used for sex selection, a practice that is virtually universally condemned by the bioethics community".[128]:121 American evangelicals supported laws in several states, adopted in 1967 and 1970, that determined abortion as legal in cases of rape, incest, and when a woman's health was in jeopardy.[131]

The Roman Catholic Church teaches that "human life must be respected and protected absolutely from the moment of conception".[132] Accordingly, it opposes procedures whose purpose is to destroy an embryo or fetus for whatever motive (even before implantation), but admits acts, such as chemotherapy or hysterectomy of a pregnant woman who has cervical cancer, which indirectly results in the death of the fetus, as morally acceptable.[133] Since the first century, the Church has affirmed that every procured abortion is a moral evil, a teaching that the Catechism of the Catholic Church declares "has not changed and remains unchangeable".[134]

A number of socially progressive mainline Protestant denominations as well as certain Jewish organizations and the group Catholics for a Free Choice have formed the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice.[135] The RCRC often works as a liberal feminist organization and in conjunction with other American feminist groups to oppose conservative religious denominations which, from their perspective, seek to suppress the natural reproductive rights of women.[136]

Alcohol, drugs and addiction[edit]

Christian theology has a long history of writing on alcohol misuse from biblical times to the present day, yet with few exceptions, "under the influence of the Enlightenment, the vast interdisciplinary literature that surrounds addiction and alcohol studies has come to exclude theology".[137]:xii Alcohol misuse is a "contemporary social problem of enormous economic significance, which exacts a high toll in human suffering".[137]:1 Social policy decisions need to include both scientific and soundly reasoned ethical principles with theology providing an important corrective to the reductionism and determinism of pragmatic atheism.[137]:199 Yet there is a remarkable absence of ethical debate concerning policy, leading many to question undo influence on the part of the alcohol industry.[137]:4

Current views on alcohol in Christianity can be divided into moderationism, abstentionism, and prohibitionism. Abstentionists and prohibitionists are sometimes lumped together as "teetotalers", sharing some similar arguments. Prohibitionists abstain from alcohol as a matter of law (God requires it), while abstentionists abstain as a matter of prudence (abstinence is the wisest and most loving way to live in the present circumstances).[138] The ethical response to alcohol's enormous popularity and widespread acceptance in the face of its social and medical harm are important issues which all persons must address directly and indirectly.[137]:4 The Christian ethic takes seriously the power of addiction to "hold people captive, and the need for an experience of a gracious 'Higher Power' as the basis for finding freedom".[137]:199

The Christian ethic concerning alcohol misuse has fluctuated from one generation to the next. In the nineteenth century, the largest proportion of Christians in all denominations resolved to remain alcohol free. While it is true that some contemporary Christians, including Pentecostals, Baptists and Methodists, continue to believe one ought to abstain from alcohol, the majority of contemporary Christians have determined that moderation is the better approach.[139][137]:4–7 Temperance campaigners of the nineteenth century would no doubt be "aghast at the sanguine stance of twenty-first century Christians" in the face of WHO estimates that "1.1 million people died of alcohol related causes in 1990, and by 2004 this had risen to 1.8 million per [year]".[137]:7

Physician assisted suicide[edit]

The arguments used to defend physician assisted suicide (PAS) are concepts of justice and mercy that can be described as a "minimalist" understanding of the terms. A minimal concept of justice respects autonomy, protects individual rights, and attempts to guarantee that each individual has the right to act according to their own preferences, but none of us are as independent or autonomous as this definition pretends. This minimalist view doesn't recognize the significance of covenant relationships and doesn't define what is good for the dying Christian; it only defines what limits to exercise as we look for what is good.[140]:348;350 Empathy toward another's suffering tells us to do something but not what to do. Such a minimalist understanding of mercy can justify almost anything.[140]:349 Once killing becomes an act of mercy, it could become difficult not to exercise such mercy toward those who have not achieved, or are past, autonomy: the handicapped, the elderly, children.[140]:350

In the Christian ethic, life and its flourishing are gifts of God, but they are not the ultimate good, and neither are suffering and death the ultimate evils. "One need not use all of one's resources against them. One need only act with integrity in the face of them".[140]:352

Persistant vegetative state[edit]

David VanDrunen explains that modern technology has treatments that enable a persistent vegetative state (PVS) which has led to questions of euthanasia and the controversial distinction between killing and letting die.[129]:197 PVS patients are in a permanent state of unconsciousness due to the loss of higher brain function; the brain stem remains alive, so they breathe, but they must receive artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH) to survive. These patients can be without other health problems and live for extended periods. Most ethicists conclude it is morally sound to decline ANH for such a patient, but some argue otherwise based on defining when death occurs.[129]:232

Environmental ethics[edit]

The twenty-first century has seen an increased concern over the possibly devastating effects of human civilization on the environment: global warming, pollution, soil erosion, deforestation, species extinction, over-population, and over-consumption are all factors in this crisis.[141]:xi Economics and environmental issues are often closely linked.[14]:326 There appears to be a strong scientific consensus that industrialized civilization has emitted enough carbon dioxide into the atmosphere to create a greenhouse effect causing global warming, yet debate rages primarily over the economic effects of limiting development.[14]:312–313 Michael Northcott says the reorientation of modern society toward recognizing the biological limits of the planet will not occur without a related quest for justice and the common good.[141]:xiii

Within a Christian ethic, the "doctrine of creation creates a presumption in favor of environmental conservation".[14]:327 The incarnation shows God loves material reality, not just spirit: "God loves trees and not just persons".[141]:129 "The relational alienation - between God and humanity, between persons, between humans and non-humans, and between non-humans" are all seen as results of the Fall of man. This situation begins to be "transformed and redeemed ... in the resurrection of Jesus Christ"...[141]:200–202 In the end, the final redemption of humanity will be accompanied by the restoration of nature.[141]:209 This Christian ethic, with its concepts of redemption of all physical reality and its manifestation in community and relation to others, is a vital corrective to modern individualism which devalues both human and non-human distinctiveness.[141]:209 As Francis Schaeffer said of the Christian ethic: "We are called to treat nature personally".[141]:127

Animal rights[edit]

Various criteria have been proposed for establishing the boundaries of personhood between the human and the non-human, but it has become widely accepted that personhood is linked to concepts of rationality and morality.[45]:1,2 In the Christian ethic, personhood is related to the nature of God, who is understood in terms of community and inter-relationship.[45]:1 Stanley Rudman argues that what it means to be human cannot be determined based on two qualities alone without reference to the full spectrum of physical, mental, social and spiritual aspects of human life.[45]:337 Personhood has both genetic and environmental dimensions, and the process of becoming more human is impossible without the help of others; it requires community.[45]:338 In the Christian ethic, a definition of personhood which emphasizes community, without disparaging reason, is preferable to one which emphasizes rationality above all else.[45]:335–337

To qualify as a being with rights, H. J. McCloskey and Joel Feinberg have concluded, one must have "interests".[45]:301 R. G. Frey, in his monograph Interests and Rights, argues the problem is in defining "interests". If the prerequisite for having "interests" includes self-consciousness, or minimal language for communication of those interests, then the case against animals having interests, and rights, is strong.[45]:302 Rudman says an emphasis on animal welfare is a better approach than the use of concepts of personhood and divine rights for addressing inhumane treatment of animals, because a strict interpretation of personhood would require animals to assume moral obligations for which they have no ability.[45]:319

Within the Christian ethic, the nature of moral community isn't limited to a community of equals: humans are not equal to God yet have community with him.[45]:319 Animals should be included in the moral community without being required to be regarded as persons.[45]:339 Based on such convictions, which include the future transformation and liberation of all creation, a Christian view is obligated to take animal welfare seriously.[45]:319

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Such as Hebrews 8:6 etc. See also Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.: "The central thought of the entire Epistle is the doctrine of the Person of Christ and His Divine mediatorial office ... There He now exercises forever His priestly office of mediator as our Advocate with the Father (vii, 24 ff)."

- ^ a b c Foster, Robert Verrell (1898). Systematic Theology. Columbia University.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Meyer, William J.; Schubert M., Schubert M. (2010). Metaphysics and the Future of Theology The Voice of Theology in Public Life. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781630878054.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Beach, Waldo (1988). Christian Ethics in the Protestant Tradition. John Knox Press. p. 8. ISBN 9780804207935.

- ^ Alexander, Larry; Moore, Michael. "Deontological Ethics". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ Ridlehoover, Charles Nathan (June 2020). "THE SERMON ON THE MOUNT AND MORAL THEOLOGY: A DEONTOLOGICAL VIRTUE ETHIC OF RESPONSE APPROACH". Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society. 63 (2): 267–280.

- ^ Ranganathan, Bharat. "Paul Ramsey's Christian Deontology". In Ranganathan, Bharat; Woodard-Lehman, D. (eds.). Scripture, Tradition, and Reason in Christian Ethics. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 163–185. ISBN 978-3-030-25192-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Gustafson, James M. (2007). Gustafson, James M.; Boer, Theodoor Adriaan; Capetz, Paul E. (eds.). Moral Discernment in the Christian Life Essays in Theological Ethics. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664230708.

- ^ Pinckaers, Servais (1995). The Sources of Christian Ethics. Catholic University of America Press. p. 8. ISBN 9780813208183.

- ^ a b c d e f Emil, Brunner (2002). The Divine Imperative A Study in Christian Ethics. Lutterworth Press. ISBN 9780718890452.

- ^ Pinckaers, Servais (1995). Noble, Mary Thomas (ed.). The Sources of Christian Ethics (paperback). Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 9780813208183.

First published in 1985 as Les sources de la morale chrétienne by University Press Fribourg, this work has been recognized by scholars worldwide as one of the most important books in the field of moral theology.

- ^ Wesleyan Quadrilateral, the Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine – A Dictionary for United Methodists, Alan K. Waltz, Copyright 1991, Abingdon Press. Revised access date: 13 September 2016

- ^ a b c d Roger E., Olson (2017). The Essentials of Christian Thought Seeing Reality Through the Biblical Story. Zondervan. ISBN 9780310521563.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Wogaman, J. Philip (2011). Christian Ethics A Historical Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664234096.

- ^ a b Kenney, John Peter. "Patristic philosophy". In Craig, Edward (ed.). The Shorter Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Taylor & Francis. p. 773. ISBN 9781134344086.

- ^ a b Long, D. Stephen (2010). Christian Ethics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199568864.