Pity

Pity is a sympathetic sorrow evoked by the suffering of others, and is used in a comparable sense to compassion, condolence or empathy - the word deriving from the Latin pietās (etymon also of piety). Self-pity is pity directed towards oneself.

Two different kinds of pity can be distinguished, "benevolent pity" and "contemptuous pity" (see Kimball), where, through insincere, pejorative usage, pity is used to connote feelings of superiority, condescension, or contempt.[1]

Psychological origins[edit]

Psychologists see pity arising in early childhood out of the infant's ability to identify with others.[2]

Psychoanalysis sees a more convoluted route to (at least some forms of) adult pity by way of the sublimation of aggression – pity serving as a kind of magic gesture intended to show how leniently one should oneself be treated by one's own conscience.[3]

Religious views[edit]

- In the West, the religious concept of pity was reinforced after acceptance of Judeo-Christian concepts of God pitying all humanity, as found initially in the Jewish tradition: “Like as a father pitieth his children, so the Lord pitieth them that fear him”.[5] The Hebrew word "Hesed" translated in the LXX by "Eleos" carries the meaning roughly equivalent to pity in the sense of compassion, mercy and loving-kindness. (See The Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament, 698a.)

- In Mahayana Buddhism, Bodhisattvas are described by the Lotus Sutra as those who “hope to win final Nirvana for all beings – for the sake of the many, for their weal and happiness, out of pity for the world”.[6]

Philosophical assessments[edit]

- Aristotle in his Rhetoric argued (Rhetoric 2.8) that before a person can feel pity for another human, the person must first have experienced suffering of a similar type, and the person must also be somewhat distanced or removed from the sufferer.[7] He defines pity as follows: "Let pity, then, be a kind of pain in the case of an apparent destructive or painful harm of one not deserving to encounter it, which one might expect oneself, or one of one's own, to suffer, and this when it seems near".[7] Aristotle also pointed out that "people pity their acquaintances, provided that they are not exceedingly close in kinship; for concerning these they are disposed as they are concerning themselves", arguing further that in order to feel pity, a person must believe that the person who is suffering does not deserve their fate.[7] Developing a traditional Greek view in his work on poetry, Aristotle also defines tragedy as a kind of imitative poetry that provokes pity and fear.[8]

- David Hume in his Treatise of Human Nature (Sect. VII Of Compassion), argued that "pity is concern for ... the misery of others without any friendship...to occasion this concern." He continues that pity "is derived from the imagination." When one observes a person in misfortune, the observer initially imagines his sorrow, even though they may not feel the same. While "we blush for the conduct of those, who behave themselves foolishly before us; and that though they show no sense of shame, nor seem in the least conscious of their folly," Hume argues "that he is the more worthy of compassion the less sensible he is of his miserable condition."[9]

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau had the following opinion of pity as opposed to love for others: "It is therefore certain that pity is a natural sentiment, which, by moderating in every individual the activity of self-love, contributes to the mutual preservation of the whole species. It is this pity which hurries us without reflection to the assistance of those we see in distress; it is this pity which, in a state of nature, stands for laws, for manners, for virtue, with this advantage, that no one is tempted to disobey her sweet and gentle voice: it is this pity which will always hinder a robust savage from plundering a feeble child, or infirm old man, of the subsistence they have acquired with pain and difficulty, if he has but the least prospect of providing for himself by any other means: it is this pity which, instead of that sublime maxim of argumentative justice, Do to others as you would have others do to you, inspires all men with that other maxim of natural goodness a great deal less perfect, but perhaps more useful, Consult your own happiness with as little prejudice as you can to that of others. " [10]

- Nietzsche pointed out that since all people to some degree value self-esteem and self-worth, pity can negatively affect any situation. Nietzsche considered his own sensitivity to pity a lifelong weakness;[11] and condemned what he called “Schopenhauer’s morality of pity...pity negates life”.[12]

Literary examples[edit]

- Juvenal considered pity the noblest aspect of human nature.[13]

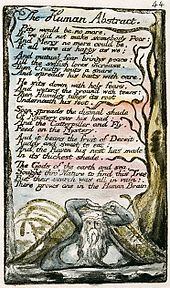

- Mystic poet William Blake was ambivalent about Pity, initially casting it in a negative role, before viewing Pity as an emotion that can draw beings together. In The Book of Urizen Pity begins when Los looks on the body of Urizen bound in chains (Urizen 13.50–51). However, Pity furthers the fall, "For pity divides the soul" (13.53), dividing Los and Enitharmon (Enitharmon is named Pity at her birth). Blake maintained that Pity disarmed righteous indignation leading to action; and, railing further against Pity in The Human Abstract, Blake exclaims: "Pity would be no more, / If we did not make somebody Poor" (1–2).

- J. R. R. Tolkien made pity – that of the hobbits for Gollum - pivotal to the action of The Lord of the Rings:[14] “It was Pity that stayed his hand...the pity of Bilbo may rule the fate of many”.[15]

- Wilfred Owen prefaced his collection of war poetry with the claim that “My subject is War and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity”[16] - something C. H. Sisson considered to verge on sentimentality.[17]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Stuff Pity!

- ^ D Goleman, Emotional Intelligence (London 1995) p. 98-9

- ^ O Fenichel, The Psychoanalytic Theory of Neurosis (London 1946) p. 476

- ^ Morris Eaves; Robert N. Essick; Joseph Viscomi (eds.). "Songs of Innocence and of Experience, copy L, object 47 (Bentley 47, Erdman 47, Keynes 47) "The Human Abstract"". William Blake Archive. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- ^ King James Version, ‘’Holy Bible’’ (USA 1979) p. 780 (Psalm 103:13)

- ^ E Conze ed., Buddhist Scriptures (Penguin 1959) p. 209

- ^ a b c David Konstan (2001). Pity Transformed. London: Duckworth. p. 181. ISBN 0-7156-2904-2.

- ^ Aristotle. Poetics, section 6.1449b24-28.

- ^ "A Treatise of Human Nature, by David Hume : B2.2.7". ebooks.adelaide.edu.au. Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- ^ Rousseau, Jean-Jacques (2004). Discourse on the origin of inequality. Mineola: Dover. p. 21.

- ^ W Kaufmann ed., The Portable Nietzsche (London 1987) p. 440

- ^ W Kaufmann ed., The Portable Nietzsche (London 1987) p. 540 and p. 573

- ^ J D Duff ed., Fourteen Satires of Juvenal (Cambridge 1925) p. 450

- ^ T Shippey, J. R. R. Tolkien (London 2001) p. 143

- ^ J. R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring (London 1991) p. 58 (Bk 1, Ch 2)

- ^ J Silkin ed, Wilfred Owen: The Poems (Penguin 1985) p. 43

- ^ C. H. Sisson English Poetry 1900-1950 (Manchester 1981) p. 83

Further reading[edit]

- Kimball, Robert H. (2004). "A Plea for Pity". Philosophy & Rhetoric. 37 (4): 301–316. doi:10.1353/par.2004.0029.

- David Konstan, Pity Transformed. London: Duckworth, 2001. pp. 181. ISBN 0-7156-2904-2.

- David Hume, An Enquiry concerning the Principles of Morals, in his Enquires concerning Human Understanding and concerning the Principles of Morals. (1751) ed. L.A. Selby-Bigge, 3rd ed. P.H. Nidditch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975 [1st]) Sec. VI Part II, p. 248, n.1.

- Stephen Tudor, Compassion and Remorse: Acknowledging the Suffering Other, Leuven, Peeters 2000.

- Lauren Wispé. The Psychology of Sympathy. Springer, 1991. ISBN 0-306-43798-8, ISBN 978-0-306-43798-4.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Pity |