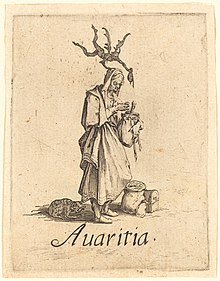

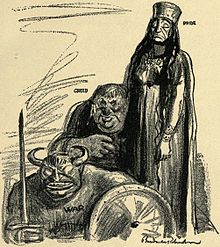

Greed

Greed (or avarice) is an uncontrolled longing for increase in the acquisition or use: of material gain (be it food, money, land, or animate/inanimate possessions); or social value, such as status, or power. Greed has been identified as undesirable throughout known human history because it creates behavior-conflict between personal and social goals.

Nature of greed[edit]

The initial motivation for (or purpose of) greed and actions associated with it may be the promotion of personal or family survival. It may at the same time be an intent to deny or obstruct competitors from potential means (for basic survival and comfort) or future opportunities; therefore being insidious or tyrannical and having a negative connotation. Alternately, the purpose could be defense or counteractive response to such obstructions being threatened by others. But regardless of purpose, greed intends to create an inequity of access or distribution to community wealth.

Modern economic thought frequently distinguishes greed from self-interest, even in its earliest works,[1][2] and spends considerable effort distinguishing the line between the two. By the mid-19th Century - affected by the phenomenological ideas of Hegel - economic and political thinkers began to define greed inherent to the structure of society as a negative and inhibitor to the development of societies.[3][4] Keynes wrote ‘The world is not so governed from above that private and social interest always coincide. It is not so managed here below that in practice they coincide’.[5] Both views continue to pose fundamental questions in today's economic thinking.[6]

As a secular psychological concept, greed is an inordinate desire to acquire or possess more than one needs. The degree of inordinance is related to the inability to control the reformulation of "wants" once desired "needs" are eliminated. Erich Fromm described greed as "a bottomless pit which exhausts the person in an endless effort to satisfy the need without ever reaching satisfaction." It is typically used to criticize those who seek excessive material wealth, although it may equally be applied to the need to feel more excessively moral, social, or otherwise better than someone else.

One individual consequence of greedy activity may be an inability to sustain any of the costs or burdens associated with that which has been or is being accumulated, leading to a backfire or destruction, whether of self or more generally. Other outcomes may include a degradation of social position, or exclusion from community protections. So, the level of "inordinance" of greed pertains to the amount of vanity, malice or burden associated with it.

Views of greed[edit]

In animals[edit]

Animal examples of greed in literary observations are frequently the attribution of human motivations to other species. The dog-in-the-manger, or piggish behaviors are typical examples. Characterizations of the wolverine (whose scientific name (Gulo gulo)) means "glutton") remark both on its outsized appetite, and its penchant for spoiling food remaining after it has gorged[7]

Ancient views[edit]

Ancient views of greed abound in nearly every culture. In Classical Greek thought; pleonexy (an unjust desire for tangible/intangible worth attaining to others) is discussed in the works of Plato and Aristotle.[8] Pan-Hellenic disapprobation of greed is seen by the mythic punishment meted to Tantalus, from whom ever-present food and water is eternally withheld. Late-Republican and Imperial politicians and historical writers fixed blame for the demise of the Roman Republic on greed for wealth and power, from Sallust and Plutarch[9] to the Gracchi and Cicero. The Persian Empires had the three-headed Zoroastrian demon Aži Dahāka (representing unslaked desire) as a fixed part of their folklore. In the Sanskrit Dharmashastras the "root of all immorality is lobha (greed)."[10], as stated in the Laws of Manu (7:49).[11] In early China, both the Shai jan jing and the Zuo zhuan texts count the greedy Taotie among the malevolent Four Perils besetting gods and men. North American Indian tales often cast bears as proponents of greed (considered a major threat in a communal society).[12] Greed is also personified by the fox in early allegoric literature of many lands.[13][14]

Greed (as a cultural quality) was often imputed as a racial pejorative by the ancient Greeks and Romans; as such it was used against Egyptians, Punics, or other Oriental peoples;[15] and generally to any enemies or people whose customs were considered strange. By the late Middle Ages the insult was widely directed towards Jews.[16]

In the Books of Moses, the commandments of the sole deity are written in the book of Exodus (20:2-17), and again in Deuteronomy (5:6-21); two of these particularly deal directly with greed, prohibiting theft and covetousness. These commandments are moral foundations of not only Judaism, but also of Christianity, Islam, Unitarian Universalism, and the Baháʼí Faith among others. The Quran advises do not spend wastefully, indeed, the wasteful are brothers of the devils..., but it also says do not make your hand [as though] chained to your neck..."[17] The Christian Gospels quote Jesus as saying, "“Watch out! Be on your guard against all kinds of greed; a man's life does not consist in the abundance of his possessions”,[18] and "For everything in the world—the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life—comes not from the Father but from the world.".[19]

Aristophanes[edit]

In the Aristophanes satire Plutus, an Athenian and his slave say to Plutus, the god of wealth, that while men may become weary of greed for love, music, figs, and other pleasures, they will never tire of greed for wealth:

If a man has thirteen talents, he has all the greater ardour to possess sixteen; if that wish is achieved, he will want forty or will complain that he knows not how to make both ends meet.[20]

Lucretius[edit]

The Roman poet Lucretius thought that the fear of dying and poverty were major drivers of greed, with dangerous consequences for morality and order:

And greed, again, and the blind lust of honours

Which force poor wretches past the bounds of law,

And, oft allies and ministers of crime,

To push through nights and days with hugest toil

To rise untrammelled to the peaks of power—

These wounds of life in no mean part are kept

Festering and open by this fright of death.[21]

Epictetus[edit]

The Roman Stoic Epictetus also saw the dangerous moral consequences of greed, and so advised the greedy to instead take pride in letting go of the desire for wealth, rather than be like the man with a fever who cannot drink his fill:

Nay, what a price the rich themselves, and those who hold office, and who live with beautiful wives, would give to despise wealth and office and the very women whom they love and win! Do you not know what the thirst of a man in a fever is like, how different from the thirst of a man in health? The healthy man drinks and his thirst is gone: the other is delighted for a moment and then grows giddy, the water turns to gall, and he vomits and has colic, and is more exceeding thirsty. Such is the condition of the man who is haunted by desire in wealth or in office, and in wedlock with a lovely woman: jealousy clings to him, fear of loss, shameful words, shameful thoughts, unseemly deeds.[22]

Medieval Europe[edit]

Augustine[edit]

In the fifth century, St. Augustine wrote:

Greed is not a defect in the gold that is desired but in the man who loves it perversely by falling from justice which he ought to esteem as incomparably superior to gold [...][23]

Aquinas[edit]

St. Thomas Aquinas states greed "is a sin against God, just as all mortal sins, in as much as man condemns things eternal for the sake of temporal things."[24]:A1 He also wrote that "greed can be “a sin directly against one’s neighbor, since one man cannot over-abound (superabundare) in external riches, without another man lacking them, for temporal goods cannot be possessed by many at the same time."

Dante[edit]

Dante's 14th century epic poem Inferno assigns those committed to the deadly sin of greed to punishment in the fourth of the nine circles of Hell. The inhabitants are misers, hoarders, and spendthrifts; they must constantly battle one another. The guiding spirit, Virgil, tells the poet these souls have lost their personality in their disorder, and are no longer recognizable: "That ignoble life, Which made them vile before, now makes them dark, And to all knowledge indiscernible."[25] In Dante's Purgatory, avaricious penitents were bound and laid face down on the ground for having concentrated too much on earthly thoughts.

Chaucer[edit]

Dante's near-contemporary, Geoffrey Chaucer, wrote of greed in his Prologue to The Pardoner's Tale these words: "Radix malorum est Cupiditas"(or “the root of all evil is greed”);[26] however the Pardoner himself serves us as a charicature of churchly greed.[27]

Early Modern Europe[edit]

Luther[edit]

Martin Luther especially condemned the greed of the usurer:

Therefore is there, on this earth, no greater enemy of man (after the devil) than a gripe-money, and usurer, for he wants to be God over all men. Turks, soldiers, and tyrants are also bad men, yet must they let the people live, and Confess that they are bad, and enemies, and do, nay, must, now and then show pity to some. But a usurer and money-glutton, such a one would have the whole world perish of hunger and thirst, misery and want, so far as in him lies, so that he may have all to himself, and every one may receive from him as from a God, and be his serf for ever. To wear fine cloaks, golden chains, rings, to wipe his mouth, to be deemed and taken for a worthy, pious man .... Usury is a great huge monster, like a werewolf, who lays waste all, more than any Cacus, Gerion or Antus. And yet decks himself out, and would be thought pious, so that people may not see where the oxen have gone, that he drags backwards into his den.[28]

Montaigne[edit]

Michel de Montaigne thought that 'it is not want, but rather abundance, that creates avarice', that 'All moneyed men I conclude to be covetous', and that:

‘tis the greatest folly imaginable to expect that fortune should ever sufficiently arm us against herself; ‘tis with our own arms that we are to fight her; accidental ones will betray us in the pinch of the business. If I lay up, ‘tis for some near and contemplated purpose; not to purchase lands, of which I have no need, but to purchase pleasure:

“Non esse cupidum, pecunia est; non esse emacem, vertigal est.”

[“Not to be covetous, is money; not to be acquisitive, is revenue.” —Cicero, Paradox., vi. 3.]

I neither am in any great apprehension of wanting, nor in desire of any more:

“Divinarum fructus est in copia; copiam declarat satietas.”

[“The fruit of riches is in abundance; satiety declares abundance.” —Idem, ibid., vi. 2.]

And I am very well pleased that this reformation in me has fallen out in an age naturally inclined to avarice, and that I see myself cleared of a folly so common to old men, and the most ridiculous of all human follies.[29]

Spinoza[edit]

Baruch Spinoza thought that the masses were concerned with money-making more than any other activity, since, he believed, it seemed to them like spending money was prerequisite for enjoying any goods and services.[30] Yet he did not consider this preoccupation to be necessarily a form of greed, and felt that the ethics of the situation were nuanced:

This result is the fault only of those, who seek money, not from poverty or to supply their necessary wants, but because they have learned the arts of gain, wherewith they bring themselves to great splendour. Certainly they nourish their bodies, according to custom, but scantily, believing that they lose as much of their wealth as they spend on the preservation of their body. But they who know the true use of money, and who fix the measure of wealth solely with regard to their actual needs, live content with little.[31]

Locke[edit]

John Locke claims that unused property is wasteful and an offence against nature, because "as anyone can make use of to any advantage of life before it spoils; so much he may by his labour fix a property in. Whatever is beyond this, is more than his share, and belongs to others.”[32]

Laurence Sterne[edit]

In the Laurence Sterne novel Tristram Shandy, the titular character describes his uncle's greed for knowledge about fortifications, saying that the 'desire of knowledge, like the thirst of riches, increases ever with the acquisition of it', that 'The more my uncle Toby pored over his map, the more he took a liking to it', and that 'The more my uncle Toby drank of this sweet fountain of science, the greater was the heat and impatience of his thirst'.[33]

Rousseau[edit]

The Swiss philosophe Jean-Jacques Rousseau compared man in the state of nature, who has no need of greed since he can find food anywhere, with man in the state of society:

for whom first necessaries have to be provided, and then superfluities; delicacies follow next, then immense wealth, then subjects, and then slaves. He enjoys not a moment's relaxation; and what is yet stranger, the less natural and pressing his wants, the more headstrong are his passions, and, still worse, the more he has it in his power to gratify them; so that after a long course of prosperity, after having swallowed up treasures and ruined multitudes, the hero ends up by cutting every throat till he finds himself, at last, sole master of the world. Such is in miniature the moral picture, if not of human life, at least of the secret pretensions of the heart of civilised man.[34]

Adam Smith[edit]

Political economist Adam Smith thought the greed for food to be limited, but the greed for other goods to be limitless:

The rich man consumes no more food than his poor neighbour. In quality it may be very different, and to select and prepare it may require more labour and art; but in quantity it is very nearly the same. But compare the spacious palace and great wardrobe of the one, with the hovel and the few rags of the other, and you will be sensible that the difference between their clothing, lodging, and household furniture, is almost as great in quantity as it is in quality. The desire of food is limited in every man by the narrow capacity of the human stomach; but the desire of the conveniencies and ornaments of building, dress, equipage, and household furniture, seems to have no limit or certain boundary.[35]

Edward Gibbon[edit]

In his account of the Sack of Rome, historian Edward Gibbon remarks that:

avarice is an insatiate and universal passion; since the enjoyment of almost every object that can afford pleasure to the different tastes and tempers of mankind may be procured by the possession of wealth. In the pillage of Rome, a just preference was given to gold and jewels, which contain the greatest value in the smallest compass and weight: but, after these portable riches had been removed by the more diligent robbers, the palaces of Rome were rudely stripped of their splendid and costly furniture.[36]

Modern Period[edit]

John Stuart Mill[edit]

In his essay Utilitarianism, John Stuart Mill writes of greed for money that:

the love of money is not only one of the strongest moving forces of human life, but money is, in many cases, desired in and for itself; the desire to possess it is often stronger than the desire to use it, and goes on increasing when all the desires which point to ends beyond it, to be compassed by it, are falling off. It may be then said truly, that money is desired not for the sake of an end, but as part of the end. From being a means to happiness, it has come to be itself a principal ingredient of the individual's conception of happiness. The same may be said of the majority of the great objects of human life—power, for example, or fame; except that to each of these there is a certain amount of immediate pleasure annexed, which has at least the semblance of being naturally inherent in them; a thing which cannot be said of money.[37]

Goethe[edit]

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's tragic play Faust, Mephistopheles, disguised as a starving man, comes to Plutus, Faust in disguise, to recite a cautionary tale about avariciously living beyond your means:

Starveling. Away from me, ye odious crew!

Welcome, I know, I never am to you.

When hearth and home were women's zone,

As Avaritia I was known.

Then did our household thrive throughout,

For much came in and naught went out!

Zealous was I for chest and bin;

'Twas even said my zeal was sin.

But since in years most recent and depraving

Woman is wont no longer to be saving

And, like each tardy payer, collars

Far more desires than she has dollars,

The husband now has much to bore him;

Wherever he looks, debts loom before him.

Her spinning-money is turned over

To grace her body or her lover;

Better she feasts and drinks still more

With all her wretched lover-corps.

Gold charms me all the more for this:

Male's now my gender, I am Avarice!

Leader of the Women.

With dragons be the dragon avaricious,

It's naught but lies, deceiving stuff!

To stir up men he comes, malicious,

Whereas men now are troublesome enough.[38]

Near the end of the play, Faust confesses to Mephistopheles:

That’s the worst suffering can bring,

Being rich, to feel we lack something.[39]

Marx[edit]

Karl Marx thought that 'avarice and the desire to get rich are the ruling passions' in the heart of every burgeoning capitalist, who later develops a 'Faustian conflict' in his heart 'between the passion for accumulation, and the desire for enjoyment' of his wealth.[40] He also stated that 'With the possibility of holding and storing up exchange-value in the shape of a particular commodity, arises also the greed for gold' and that 'Hard work, saving, and avarice are, therefore, [the hoarder's] three cardinal virtues, and to sell much and buy little the sum of his political economy.'[41] Marx discussed what he saw as the specific nature of the greed of capitalists thusly:

Use-values must therefore never be looked upon as the real aim of the capitalist; neither must the profit on any single transaction. The restless never-ending process of profit-making alone is what he aims at. This boundless greed after riches, this passionate chase after exchange-value, is common to the capitalist and the miser; but while the miser is merely a capitalist gone mad, the capitalist is a rational miser. The never-ending augmentation of exchange-value, which the miser strives after, by seeking to save his money from circulation, is attained by the more acute capitalist, by constantly throwing it afresh into circulation.[42]

Meher Baba[edit]

Meher Baba dictated that "Greed is a state of restlessness of the heart, and it consists mainly of craving for power and possessions. Possessions and power are sought for the fulfillment of desires. Man is only partially satisfied in his attempt to have the fulfillment of his desires, and this partial satisfaction fans and increases the flame of craving instead of extinguishing it. Thus greed always finds an endless field of conquest and leaves the man endlessly dissatisfied. The chief expressions of greed are related to the emotional part of man."[43]

Ivan Boesky[edit]

Ivan Boesky famously defended greed in an 18 May 1986 commencement address at the UC Berkeley's School of Business Administration, in which he said, "Greed is all right, by the way. I want you to know that. I think greed is healthy. You can be greedy and still feel good about yourself".[44] This speech inspired the 1987 film Wall Street, which features the famous line spoken by Gordon Gekko: "Greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right, greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms; greed for life, for money, for love, knowledge has marked the upward surge of mankind."[45]

Inspirations[edit]

Scavenging and hoarding of materials or objects, theft and robbery, especially by means of violence, trickery, or manipulation of authority are all actions that may be inspired by greed. Such misdeeds can include simony, where one profits from soliciting goods within the actual confines of a church. A well-known example of greed is the pirate Hendrick Lucifer, who fought for hours to acquire Cuban gold, becoming mortally wounded in the process. He died of his wounds hours after having transferred the booty to his ship.[46]

Genetics[edit]

Some research suggests there is a genetic basis for greed. It is possible people who have a shorter version of the ruthlessness gene (AVPR1a) may behave more selfishly.[47]

See also[edit]

- Contempt

- Financialization

- Interest

- Narcissism

- Genoeconomics

- Pleonexia

- Seven deadly sins

- American Greed

- Greed, 1924 film

- Greed, 2019 film

- Greed (game show)

- Ojukokoro (Greed), film

- Greed (Jelinek novel), novel

- Greed is good

- Theft

- Mr. Krabs

- Usury

References[edit]

- ^ Charles de Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 338

- ^ Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (New York: Modern Library, 1965), p.651

- ^ Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class (1934 ed.), p. 36

- ^ Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto, London, 1848

- ^ Keynes, The End of Laissez-Faire, http://www.panarchy.org/keynes/laissezfaire.1926.html

- ^ http://piotr-evdokimov.com/greed.pdf

- ^ https://www.visionlearning.com/blog/2014/12/17/wolverines-give-insight-evolution-greed/

- ^ https://countercurrents.org/2018/10/the-evolution-of-greed-from-aristotle-to-gordon-gekko

- ^ http://www.reallycoolblog.com/greed-power-and-prestige-explaining-the-fall-of-the-roman-republic/

- ^ https://qz.com/india/1041986/wealth-interest-and-greed-the-dharma-of-doing-business-in-medieval-india/

- ^ https://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/manu/manu07.htm

- ^ http://www.native-languages.org/legends-greed.htm

- ^ Casal, U. A. (1959). "The Goblin Fox and Badger and Other Witch Animals of Japan". Folklore Studies. 18: 1–93. doi:10.2307/1177429. JSTOR 1177429.

- ^ https://www.behtarlife.com/2016/12/foolish-and-greedy-fox-hindi-story.html

- ^ The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity, Benjamin Isaac, Princeton University Press, 2004; ISBN 0691-11691-1

- ^ https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/usury-and-moneylending-in-judaism/

- ^ https://quran.com/17/26-36?translations=20

- ^ Luke 12:15

- ^ John 2:16

- ^ Aristophanes. Plutus. The Internet Classics Archive.

- ^ Lucretius. Of the Nature of Things, Book III. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Epictetus. The Discourses of Epictetus, Book IV, Chapter 9. Translated by Percy Ewing Matheson.Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- ^ https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/870546-greed-is-not-a-defect-in-the-gold-that-is,

- ^ Thomas Aquinas. "The Summa Theologica II-II.Q118 (The vices opposed to liberality, and in the first place, of covetousness)" (1920, Second and Revised ed.). New Advent.

- ^ https://www.owleyes.org/text/dantes-inferno/read/canto-7#root-422366-1

- ^ https://sites.fas.harvard.edu/~chaucer/teachslf/pard-par.htm, line 426

- ^ https://partiallyexaminedlife.com/2018/11/23/a-philosophical-horror-story-chaucers-the-pardoners-tale/

- ^ In Karl Marx, Capital, Volume 1, Chapter 24, Footnote 20. Translated by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling. Edited by Frederick Engels. Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Michel de Montaigne. Essays of Michel de Montaigne. Book I, Chapter XL. Translated by Charles Cotton. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Baruch Spinoza. The Ethics, Book IV, Appendix, XXVIII. 'Now for providing these nourishments the strength of each individual would hardly suffice, if men did not lend one another mutual aid. But money has furnished us with a token for everything: hence it is with the notion of money, that the mind of the multitude is chiefly engrossed: nay, it can hardly conceive any kind of pleasure, which is not accompanied with the idea of money as cause.' Translated by R. H. M. Elwes. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Spinoza. The Ethics, Book IV, Appendix, XXIX.

- ^ https://www.earlymoderntexts.com/assets/pdfs/locke1689a.pdf, Chapter 5

- ^ Laurence Sterne. Tristram Shandy, Book II, Chapter III. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Jean-Jacques Rousseau. On the Origin of Inequality. Appendix. Translated by G. D. H. Cole. American University of Beirut.

- ^ Adam Smith. The Wealth of Nations, Book I, Chapter XI, Part II. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Edward Gibbon. History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Volume III, Chapter XXXI, Part IV. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ John Stuart Mill. Utilitarianism, Chapter IV. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Faust, Part II, Section 4. Translated by George Madison Priest. Goethe (Re)Collected.

- ^ Goethe. Faust, Part II, Act V, Scene III. Translated by A. S. Kline. Goethe (Re)Collected.

- ^ Karl Marx. Capital, Volume 1, Part 1, Chapter 24. Translated by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling. Edited by Frederick Engels. Marxists Internet Archive.

- ^ Karl Marx. Capital, Volume 1, Part 1, Chapter III. 'In order that gold may be held as money, and made to form a hoard, it must be prevented from circulating, or from transforming itself into a means of enjoyment. The hoarder, therefore, makes a sacrifice of the lusts of the flesh to his gold fetish. He acts in earnest up to the Gospel of abstention. On the other hand, he can withdraw from circulation no more than what he has thrown into it in the shape of commodities. The more he produces, the more he is able to sell. Hard work, saving, and avarice are, therefore, his three cardinal virtues, and to sell much and buy little the sum of his political economy.'

- ^ Marx. Capital, Volume 1, Part 2, Chapter IV.

- ^ Baba, Meher (1967). Discourses. Volume II. San Francisco: Sufism Reoriented. p. 27.

- ^ Gabriel, Satya J (November 21, 2001). "Oliver Stone's Wall Street and the Market for Corporate Control". Economics in Popular Film. Mount Holyoke. Retrieved 2008-12-10.

- ^ Ross, Brian (November 11, 2005). "Greed on Wall Street". ABC News. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- ^ Dreamtheimpossible (September 14, 2011). "Examples of greed". Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ 'Ruthlessness gene' discovered