Apathy

Apathy is a lack of feeling, emotion, interest, or concern about something. It is a state of indifference, or the suppression of emotions such as concern, excitement, motivation, or passion. An apathetic individual has an absence of interest in or concern about emotional, social, spiritual, philosophical, virtual, or physical life and the world.

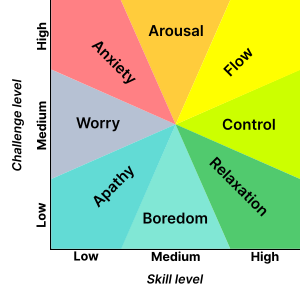

The apathetic may lack a sense of purpose, worth, or meaning in their life. And may also exhibit insensibility or sluggishness. In positive psychology, apathy is described as a result of the individuals feeling they do not possess the level of skill required to confront a challenge (i.e. "flow"). It may also be a result of perceiving no challenge at all (e.g. the challenge is irrelevant to them, or conversely, they have learned helplessness). Apathy is something that all people face in some capacity and is a natural response to disappointment, dejection, and stress. As a response, apathy is a way to forget about these negative feelings.[citation needed] This type of common apathy is usually felt only in the short term, but sometimes it becomes a long-term or even lifelong state, often leading to deeper social and psychological issues.

Apathy should be distinguished from reduced affect display, which refers to reduced emotional expression but not necessarily reduced emotion.

Pathological apathy, characterised by extreme forms of apathy, is now known to occur in many different brain disorders,[2] including neurodegenerative conditions often associated with dementia such as Alzheimer's disease,[3] and psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia.[4] Although many patients with pathological apathy also suffer from depression, several studies have shown that the two syndromes are dissociable: apathy can occur independently of depression and vice versa.[2]

Etymology[edit]

Although the word apathy was first used in 1594[5] and is derived from the Greek ἀπάθεια (apatheia), from ἀπάθης (apathēs, "without feeling" from a- ("without, not") and pathos ("emotion")),[6] it is important not to confuse the two terms. Also meaning "absence of passion," "apathy" or "insensibility" in Greek, the term apatheia was used by the Stoics to signify a (desirable) state of indifference towards events and things which lie outside one's control (that is, according to their philosophy, all things exterior, one being only responsible for one's own representations and judgments).[7] In contrast to apathy, apatheia is considered a virtue, especially in Orthodox monasticism.[citation needed] In the Philokalia the word dispassion is used for apatheia, so as not to confuse it with apathy.[citation needed]

History and other views[edit]

Christians have historically condemned apathy as a deficiency of love and devotion to God and his works.[8] This interpretation of apathy is also referred to as Sloth and is listed among the Seven Deadly Sins. Clemens Alexandrinus used the term to draw to Christianity philosophers who aspired after virtue.

The modern concept of apathy became more well known after World War I, when it was one of the various forms of "shell shock". Soldiers who lived in the trenches amidst the bombing and machine gun fire, and who saw the battlefields strewn with dead and maimed comrades, developed a sense of disconnected numbness and indifference to normal social interaction when they returned from combat.

In 1950, US novelist John Dos Passos wrote: "Apathy is one of the characteristic responses of any living organism when it is subjected to stimuli too intense or too complicated to cope with. The cure for apathy is comprehension."

Technology[edit]

Apathy is a normal way for humans to cope with stress. Being able to "shrug off" disappointments is considered an important step in moving people forward and driving them to try other activities and achieve new goals. Coping seems to be one of the most important aspects of getting over a tragedy and an apathetic reaction may be expected. With the addition of the handheld device and the screen between people, apathy has also become a common occurrence on the net as users observe others being bullied, slandered, threatened or sent disturbing images. The bystander effect grows to an apathetic level as people lose interest in caring for others who are not in their "circle" and may even participate in their harassment.

Social origin[edit]

There may be other factors contributing to a person's apathy. Activist David Meslin argues that people often care, and that apathy is often the result of social systems actively obstructing engagement and involvement. He describes various obstacles that prevent people from knowing how or why they might get involved in something. Meslin focuses on design choices that unintentionally or intentionally exclude people. These include: capitalistic media systems that have no provisions for ideas that are not immediately (monetarily) profitable, government and political media (e.g. notices) that make it difficult for potentially interested individuals to find relevant information, and media portrayals of heroes as "chosen" by outside forces rather than self-motivated. He moves that we redefine social apathy to think of it, not as a population that is stupid or lazy, but as a result of poorly designed systems that fail to invite others to participate.[9][10]

Apathy has been socially viewed as worse than things such as hate or anger. Not caring whatsoever, in the eyes of some, is even worse than having distaste for something. Author Leo Buscaglia is quoted as saying "I have a very strong feeling that the opposite of love is not hate-it's apathy. It's not giving a damn." Helen Keller claimed that apathy is the "worst of them all" when it comes to the various evils of the world. French social commentator and political thinker Charles de Montesquieu stated that "the tyranny of a prince in an oligarchy is not so dangerous to the public welfare as the apathy of a citizen in the democracy."[11] As can be seen by these quotes and various others, the social implications of apathy are great. Many people believe that not caring at all can be worse for society than individuals who are overpowering or hateful.

In the school system[edit]

This section relies largely or entirely upon a single source. (March 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Apathy in students, especially those in high school, is a growing problem .[citation needed] Apathy in schools is most easily recognized by students being unmotivated or, quite commonly, being motivated by outside factors. For example, when asked about their motivation for doing well in school, fifty percent of students cited outside sources such as "college acceptance" or "good grades". On the contrary, only fourteen percent cited "gaining an understanding of content knowledge or learning subject material" as their motivation to do well in school. As a result of these outside sources, and not a genuine desire for knowledge, students often do the minimum amount of work necessary to get by in their classes.[citation needed] This then leads to average grades and test grades but no real grasping of knowledge.[citation needed] Many students cited that "assignments/content was irrelevant or meaningless" and that this was the cause of their apathetic attitudes toward their schooling. These apathetic attitudes lead to teacher and parent frustration.[12] Other causes of apathy in students include situations within their home life, media influences, peer influences, and school struggles and failures. Some of the signs for apathetic students include declining grades, skipping classes, routine illness, and behavioral changes both in school and at home.

Bystander[edit]

Also known as the bystander effect, bystander apathy occurs when, during an emergency, those standing by do nothing to help but instead stand by and watch. Sometimes this can be caused by one bystander observing other bystanders and imitating their behavior. If other people are not acting in a way that makes the situation seem like an emergency that needs attention, often other bystanders will act in the same way.[13] The diffusion to responsibility can also be to blame for bystander apathy. The more people that are around in emergency situations, the more likely individuals are to think that someone else will help so they do not need to. This theory was popularized by social psychologists in response to the 1964 Kitty Genovese murder. The murder took place in New York and the victim, Genovese, was stabbed to death as bystanders reportedly stood by and did nothing to stop the situation or even call the police.[14] Latane and Darley are the two psychologists who did research on this theory. They performed different experiments that placed people into situations where they had the opportunity to intervene or do nothing. The individuals in the experiment were either by themselves, with a stranger(s), with a friend, or with a confederate. The experiments ultimately led them to the conclusion that there are many social and situational factors that are behind whether a person will react in an emergency situation or simply remain apathetic to what is occurring.

Communication[edit]

Apathy is one psychological barrier to communication. An apathetic listener creates a communication barrier by not caring or paying attention to what they are being told. An apathetic speaker, on the other hand, tends to not relate information well and, in their lack of interest, may leave out key pieces of information that need to be communicated. Within groups, an apathetic communicator can be detrimental. Their lack of interest or passion can inhibit the other group members in what they are trying to accomplish. Within interpersonal communication, an apathetic listener can make the other feel that they are not cared for or about. Overall, apathy is a dangerous barrier to successful communication. Apathetic speakers and listeners are individuals that have no care for what they are trying to communicate, or what is being communicated to them.

Measurement of Apathy[edit]

Several different questionnaires and clinical interview instruments have been used to measure pathological apathy or, more recently, apathy in healthy people.

Apathy Evaluation Scale[edit]

Developed by Robert Marin in 1991, the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) was the first method developed to measure apathy in clinical populations. Centered around evaluation, the scale can either be self-informed or other-informed. The three versions of the test include self, informant such as a family member, and clinician. The scale is based around questionnaires that ask about topics including interest, motivation, socialization, and how the individual spends their time. The individual or informant answers on a scale of "not at all", "slightly", "somewhat" or "a lot". Each item on the evaluation is created with positive or negative syntax and deals with cognition, behavior, and emotion. Each item is then scored and, based on the score, the individual's level of apathy can be evaluated.[15]

Apathy Motivation Index[edit]

The Apathy Motivation Index (AMI) was developed to measure different dimensions of apathy in healthy people. Factor analysis identified three distinct axes of apathy: behavioural, social and emotional.[16] The AMI has since been used to examine apathy in patients with Parkinson's disease who, overall, showed evidence of behavioural and social apathy, but not emotional apathy.[17]

Dimensional Apathy Scale[edit]

The Dimensional Apathy Scale (DAS) is a multidimensional apathy instrument for measuring subtypes of apathy in different clinical populations and healthy adults. It was developed using factor analysis, quantifying Executive apathy (lack of motivation for planning, organising and attention), Emotional apathy (emotional indifference, neutrality, flatness or blunting) and Initiation apathy (lack of motivation for self-generation of thought/action). There is a self-rated version of the DAS[18] and an informant/carer-rated version of the DAS.[19] Further a clinical brief DAS has also been developed.[20] It has been validated for use in motor neurone disease, dementia and Parkinson's disease, showing to differentiate profiles of apathy subtypes between these conditions[21]

Medical aspects | Pathological apathy[edit]

Depression[edit]

Mental health journalist and author John McManamy argues that although psychiatrists do not explicitly deal with the condition of apathy, it is a psychological problem for some depressed people, in which they get a sense that "nothing matters", the "lack of will to go on and the inability to care about the consequences".[22] He describes depressed people who "...cannot seem to make [themselves] do anything", who "can't complete anything", and who do not "feel any excitement about seeing loved ones".[22] He acknowledges that the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders does not discuss apathy.

In a Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences article from 1991, Robert Marin, MD, claimed that pathological apathy occurs due to brain damage or neuropsychiatric illnesses such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, or Huntington's disease, stroke. Marin argues that apathy is a syndrome associated with many different brain disorders.[22] This has now been shown to be the case across a range of neurological and psychiatric conditions.[2]

A review article by Robert van Reekum, MD, et al. from the University of Toronto in the Journal of Neuropsychiatry (2005) claimed that an obvious relationship between depression and apathy exists in some populations.[23] However, although many patients with depression suffer from apathy, several studies have shown that apathy can occur independently of depression, and vice versa.[2]

Apathy can be associated with depression, a manifestation of negative disorders in schizophrenia, or a symptom of various somatic and neurological disorders.[24][2]

Alzheimer's disease[edit]

Depending upon how it has been measured, apathy affects 19–88% percent of individuals with Alzheimer's disease (mean prevalence of 49% across different studies).[3] It is a neuropsychiatric symptom associated with functional impairment. Brain imaging studies have demonstrated changes in the anterior cingulate cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and ventral striatum in Alzheimer's patients with apathy.[25] Cholinesterase inhibitors, used as the first line of treatment for the cognitive symptoms associated with dementia, have also shown some modest benefit for behavior disturbances such as apathy.[26] The effects of donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine have all been assessed but, overall, the findings have been inconsistent, and it is estimated that apathy in ~60% of Alzheimer's patients does not respond to treatment with these drugs.[3] Methylphenidate, a dopamine and noradrenaline reuptake blocker, has received increasing interest for the treatment of apathy. Management of apathetic symptoms using methylphenidate has shown promise in randomized placebo controlled trials of Alzheimer's patients.[27][28][29] A phase III multi-centered randomized placebo-controlled trial of methylphenidate for the treatment of apathy is currently underway and planned for completion in August 2020.[30]

Anxiety[edit]

While apathy and anxiety may appear to be separate, and different, states of being, there are many ways that severe anxiety can cause apathy. First, the emotional fatigue that so often accompanies severe anxiety leads to one's emotions being worn out, thus leading to apathy. Second, the low serotonin levels associated with anxiety often lead to less passion and interest in the activities in one's life which can be seen as apathy. Third, negative thinking and distractions associated with anxiety can ultimately lead to a decrease in one's overall happiness which can then lead to an apathetic outlook about one's life. Finally, the difficulty enjoying activities that individuals with anxiety often face can lead to them doing these activities much less often and can give them a sense of apathy about their lives. Even behavioral apathy may be found in individuals with anxiety in the form of them not wanting to make efforts to treat their anxiety.[31]

Other[edit]

Often, apathy is felt after witnessing horrific acts, such as the killing or maiming of people during a war, e.g. posttraumatic stress disorder. It is also known to be a distinct psychiatric syndrome[citation needed] that is associated with many conditions, some of which are: CADASIL syndrome, depression, Alzheimer's disease, Chagas disease, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, dementia (and dementias such as Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, and frontotemporal dementia), Korsakoff's syndrome, excessive vitamin D, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, general fatigue, Huntington's disease, Pick's disease, progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), brain damage, schizophrenia, schizoid personality disorder, bipolar disorder,[citation needed] autism spectrum disorders, ADHD, and others. Some medications and the heavy use of drugs such as opiates or GABA-ergic drugs may bring apathy as a side effect.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Csikszentmihalyi, M., Finding Flow, 1997, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e Husain, Masud; Roiser, Jonathan P. (26 June 2018). "Neuroscience of apathy and anhedonia: a transdiagnostic approach". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 19 (8): 470–484. doi:10.1038/s41583-018-0029-9. PMID 29946157. S2CID 49428707.

- ^ a b c Nobis, Lisa; Husain, Masud (2018). "Apathy in Alzheimer's disease". Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 22: 7–13. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.12.007. PMC 6095925. PMID 30123816.

- ^ Bortolon, C.; Macgregor, A.; Capdevielle, D.; Raffard, S. (2018). "Apathy in schizophrenia: A review of neuropsychological and neuroanatomical studies". Neuropsychologia. 118 (Pt B): 22–33. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.09.033. PMID 28966139. S2CID 13411386.

- ^ "Apathy - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, ἀπάθ-εια". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ William Fleming (1857). The vocabulary of philosophy, mental, moral, and metaphysical. p.&34. Reprinted by Kessinger Publishing as paperback (2006; ISBN 978-1-4286-3324-7) and in hardcover (2007; ISBN 978-0-548-12371-3).

- ^ "Greek Lexicon :: G543 (KJV)". V3.blueletterbible.org. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Dave Meslin: The antidote to apathy | Video on". Ted.com. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Dave Meslin | Profile on". Ted.com. 17 July 2010. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "12 Famous Quotes About Apathy". psysci.co. 30 April 2015. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ^ "Finding the Root Cause of Student Apathy". Pan.intrasun.tcnj.edu. Archived from the original on 24 March 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Latane and Darley: Bystander Apathy". Faculty.babson.edu. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Bystander Effect". Psychology Today. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Apathy Evaluation Scale (Self rated)" (PDF). Dementia-assessment.com.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ Ang, Y.S.; Lockwood, P.; Apps, M.A.; Muhammed, K.; Husain, M. (2017). "Distinct Subtypes of Apathy Revealed by the Apathy Motivation Index". PLOS One. 12 (1): e0169938. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1269938A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169938. PMC 5226790. PMID 28076387.

- ^ Ang, Y.S.; Lockwood, P.L.; Kienast, A.; Plant, O.; Drew, D.; Slavkova, E.; Tamm, M.; Husain, M. (2018). "Differential impact of behavioral, social, and emotional apathy on Parkinson's disease". Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology. 5 (10): 1286–1291. doi:10.1002/acn3.626. PMC 6186939. PMID 30349863.

- ^ Radakovic, R.; Abrahams, S. (2014). "Developing a new apathy measurement scale: DAS" (PDF). Psychiatry Research. 219 (3): 658–63. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.06.010. PMID 24972546. S2CID 16313833.

- ^ Radakovic, R.; Stephenson, L.; Colville, S.; Swingler, R.; Chandran, S.; Abrahams, S. (2016). "Multidimensional apathy in ALS: validation of the Dimensional Apathy Scale" (PDF). Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 87 (6): 663–9. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2015-310772. PMID 26203157. S2CID 15540782.

- ^ Radakovic, R.; McGrory, S.; Chandran, S.; Swingler, R.; Pal, S.; Stephenson, L.; Colville, S.; Newton, J.; Starr, J.M.; Abrahams, S. (2020). "The brief Dimensional Apathy Scale: A short clinical assessment of apathy" (PDF). The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 34 (2): 423–435. doi:10.1080/13854046.2019.1621382. PMID 26203157. S2CID 173994534.

- ^ Radakovic, R.; Abrahams, S. (2018). "Multidimensional apathy: evidence from neurodegenerative disease" (PDF). Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 22: 42–49. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.12.022. S2CID 53173573.

- ^ a b c John McManamy. "Apathy Matters - Apathy and Depression: Psychiatry may not care about apathy, but that doesn't mean you shouldn't Archived 20 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine".[self-published source?]

- ^ van Reekum, Robert; Stuss, Donald T.; Ostrander, Laurie (February 2005). "Apathy: Why Care?". The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 17 (1): 7–19. doi:10.1176/jnp.17.1.7. PMID 15746478.

- ^ Andersson, S.; Krogstad, J. M.; Finset, A. (1 March 1999). "Apathy and depressed mood in acquired brain damage: relationship to lesion localization and psychophysiological reactivity". Psychological Medicine. 29 (2): 447–456. doi:10.1017/s0033291798008046. PMID 10218936.

- ^ Le Heron, Campbell; Apps, Matthew; Husain, Masud (2018). "The anatomy of apathy: A neurocognitive framework for amotivated behaviour". Neuropsychologia. 118 (Pt B): 54–67. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.07.003. PMC 6200857. PMID 28689673.

- ^ Malloy, Paul F. (2 November 2005). "Apathy and Its Treatment in Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias". Psychiatric Times.

- ^ Herrmann, Nathan; Rothenburg, Lana S.; Black, Sandra E.; Ryan, Michelle; Liu, Barbara A.; Busto, Usoa E.; Lanctôt, Krista L. (June 2008). "Methylphenidate for the Treatment of Apathy in Alzheimer Disease". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 28 (3): 296–301. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e318172b479. PMID 18480686. S2CID 30971352.

- ^ Rosenberg, Paul B.; Lanctôt, Krista L.; Drye, Lea T.; Herrmann, Nathan; Scherer, Roberta W.; Bachman, David L.; Mintzer, Jacobo E.; ADMET, Investigators (15 August 2013). "Safety and Efficacy of Methylphenidate for Apathy in Alzheimer's Disease". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 74 (8): 810–816. doi:10.4088/JCP.12m08099. PMC 3902018. PMID 24021498.

- ^ Lanctôt, Krista L.; Chau, Sarah A.; Herrmann, Nathan; Drye, Lea T.; Rosenberg, Paul B.; Scherer, Roberta W.; Black, Sandra E.; Vaidya, Vijay; Bachman, David L.; Mintzer, Jacobo E. (29 October 2013). "Effect of methylphenidate on attention in apathetic AD patients in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial". International Psychogeriatrics. 26 (2): 239–246. doi:10.1017/S1041610213001762. PMC 3927455. PMID 24169147.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT02346201 for "Apathy in Dementia Methylphenidate Trial 2 (ADMET2)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ "Apathy: Anxiety's Unusual Symptom". Calm Clinic. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

References[edit]

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al. Missing or empty

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al. Missing or empty |title=(help)

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Apathy |

- The Roots of Apathy – Essay By David O. Solmitz

- Apathy – McMan's Depression and Bipolar Web, by John McManamy