Try it here! If you like it, share it.

Bringing 100 Years of Librarian-Knowledge to Life

By Nick Norman with Drini Cami & Mek

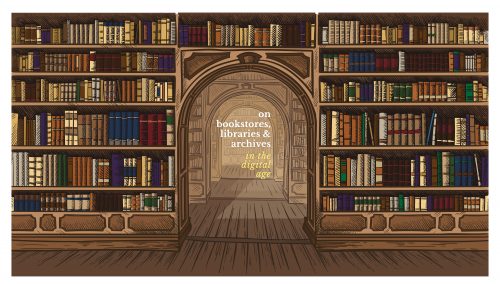

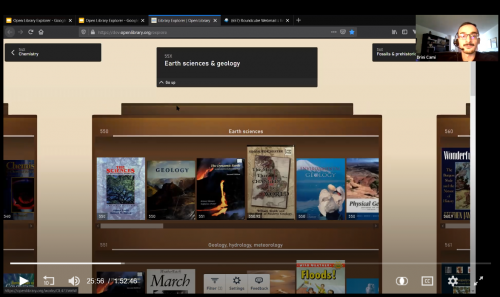

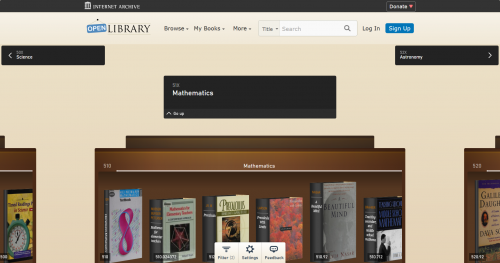

At the Library Leaders Forum 2020 (demo), Open Library unveiled the beta for what it’s calling the Library Explorer: an immersive interface which powerfully recreates and enhances the experience of navigating a physical library. If the tagline doesn’t grab your attention, wait until you see it in action:

Get Ready to Explore

In this article, we’ll give you a tour of the Open Library Explorer and teach you how one may take full advantage of its features. You’ll also get a crash course on the 100+ years of library history which led to its innovation and an opportunity to test-drive it for yourself. So let’s get started!

What better way to set the stage than by taking a trip down memory lane to the last time you were able to visit your local public library. As you pass the front desk, a friendly librarian scribbles some numbers on a piece of paper which they hand to you and points you towards a relevant section. With the list of library call numbers in your hand as your compass, you eagerly make your way through waves of towering bookshelves. Suddenly, you depart from reality and find yourself navigating through a sea of books, discovering treasures you didn’t even know existed.

Before you know it, one book gets stuffed under one arm, two more books go under your other arm, and a few more books get positioned securely between your knees. You’re doing the math to see how close you are to your check-out limit. Remember those days?

What if you could replicate that same library experience and access it every single day, from the convenience of your web browser? Well, thanks to the new Open Library Explorer, you can experience the joys of a physical library right in your web browser, as well as leverage superpowers which enable you to explore in ways which may have previously been impossible.

Before we dive into the bells-and-whistles of the Library Explorer, it’s worth learning how and why such innovations came to be.

Who needs Library Explorer?

This year we’ve seen systems stressed to their max due to the COVID-19 pandemic. With libraries and schools closing their doors globally and stay-at-home orders hampering our access, there has been a paradigm shift in the needs of researchers, educators, students, and families to access fundamental resources online. Getting this information online is a challenge in and of itself. Making it easy to discover and use materials online is another entirely. How does one faithfully compress the entire experience of a reliable, unbiased, expansive public library and its helpful, friendly staff into a 14” computer screen?

Some sites, like Netflix or YouTube, solve this problem with recommendation engines that populate information based on what people have previously seen or searched. Consequently, readers may unknowingly find themselves caught in a sort of “algorithmic bubble.”

An algorithmic bubble (or “filter bubble”) is a state of intellectual or informational isolation that’s perpetuated by personalized content. Algorithmic bubbles can make it difficult for users to access information beyond their own opinions—effectively isolating them in their own cultural or ideological silos.

Drini Cami, the creator of Library Explorer, says that users’ caught inside these algorithmic bubbles “won’t be exposed to information that is completely foreign to [them]. There is no way to systematically and feasibly explore.” Hence the reasoning behind the Library Explorer’s intelligence comes out of a need to discover information without the constraints of algorithmic bubbles.

As readers are exposed to more information, the question becomes, how can readers fully explore swaths of new information and still enjoy the experience?

Let’s take a look at how the Library Explorer tackles that half of the problem.

Humanity’s Knowledge Brought to Life

Earlier this year, Open Library added the ability to search materials by both Dewey Decimal Classification and Library of Congress Classification. These systems contain embedded within them over 100 years of librarian experience, and provide a systematized approach to sort through the entirety of humanity’s knowledge embedded in books.

It is important to note, the systematization of knowledge alone does not necessarily make it easily discoverable. This is what makes the Library Explorer so special. Its digital interface opens the door for readers to seamlessly navigate centuries of books anywhere online.

Thanks to innovations such as the Library Explorer, readers can explore more books and access more knowledge with a better experience.

A tour of Library Explorer’s features

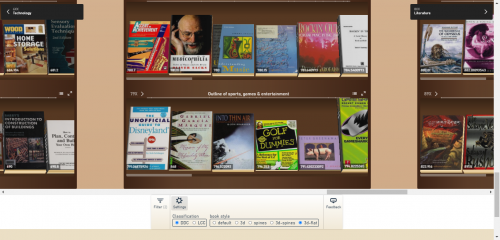

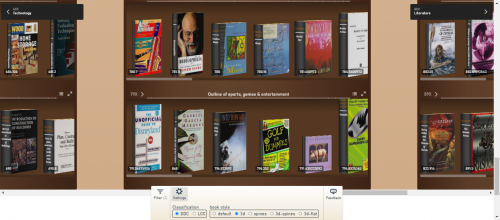

If you’re pulling up a chair for the first time, the Library Explorer presents you with tall, clickable bookshelves situated across your screen. Each shelf has its own identity that can morph into new classes of books and subject categories with a single click. And that’s only the beginning of what it offers.

In addition to those smart filters, the Library Explorer wants you to steer the ship… not the other way around. In other words, you can personalize single rows of books, expand entire shelves, or construct an entire library-experience that evolves around your exact interests. You can custom tailor your own personal library from the comfort of your device, wherever you may be.

Quick question: as a kid, did you ever layout your newly checked-out library books on your bed to admire them? Well, the creators behind the Library Explorer found a way to mimic that same experience. If you so choose, you can zoom out of the Library Explorer interface to get a complete view of the library you’ve constructed.

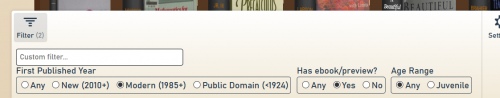

Let’s explore one more set of cool features the Library Explorer offers by clicking on the “Filter” icon at the bottom of the page.

By selecting “Juvenile,” you can instantly transform your entire library into a children’s library, but keep all the useful organization and structure provided by the bookshelves. It’s as if your own personal librarian ran in at lightning speed and removed every book from each shelf that didn’t meet your criteria. Or you may type in “subject:biography” and suddenly your entire library shows you a tailored collection of just biographies on every subject. The sky is your limit.

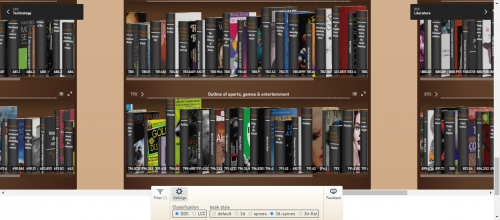

If you click on the Settings tab, you’re given several options to customize the look and feel of your personal Library Explorer. You can switch between using Library of Congress or Dewey Decimal classification to organize your shelves. You can also choose from a variety of delightful options to see your books in 3D. Each book has the correct thickness determined by its actual number of pages. To see your favorite book in 3D, click the settings icon at the bottom of the screen and then press the 3D button.

Library Explorer’s 3D view

Maybe you’ve experienced a time where you had limited space in your book bag. Perhaps because of that, you chose to wait on checking out heavier books. Or, maybe you judged a book’s strength of knowledge based on its thickness. If that’s you, guess what? The Open Library Explorer lets you do that.

It gets personal…

The primary goal of the Library Explorer was to create an experimental interface that ‘opens the door’ for readers to locate new books and engage with their favorite books. The Library Explorer is one of many steps that both the Internet Archive and the Open Library have made towards making knowledge easy to discover.

As you know, such innovation couldn’t be possible without people who believe in the necessity of reading. Here is a list of the names of those who contributed to the creation of the Library Explorer:

- Drini Cami, Open Library Developer and Library Explorer Creator

- Mek Karpeles, Open Library Program Lead

- Jim Shelton, UX Designer, Internet Archive

- Ziyad Basheer, Product Designer

- Tinnei Pang, Illustrator and Product Designer

- James Hill-Khurana, Product Designer

- Nick Norman, Open Library Storyteller & Volunteer Communications Lead

Well, this is the moment you’ve been waiting for. Go here and give the Library Explorer a beta test-run. Also, follow @OpenLibrary on Twitter to learn about other features as soon as they’re released.

But before you go… in the comments below, tell us your favorite library experience. We’d love to hear!