On March 24, 2020, the Internet Archive

announced that it would "suspend waitlists for the 1.4 million (and growing) books in our lending library," a service they then named

The National Emergency Library. These books were previously available for lending on a one-to-one basis with the physical book owned by the Archive, and as with physical books users would have to wait for the book to be returned before they could borrow it. Worded as a suspension of waitlists due to the closure of schools and libraries caused by the presence of the coronavirus-19, this announcement essentially eliminated the one-to-one nature of the Archive's

Controlled Digital Lending program. Publishers were already making

threatening noises about the digital lending when it adhered to lending limitations, and surely will be even more incensed about this unrestricted lending.

I am not going to comment on the legality of the Internet Archive's lending practices. Legal minds, perhaps motivated by future lawsuits, will weigh in on that. I do, however, have much to say on the use of the term "library" for this set of books. It's a topic worthy of a lengthy treatment, but I'll give only a brief account here.

LIBRARY … BIBLIOTHÈQUE … BIBLIOTEK

The

roots “LIBR…” and “BIBLIO…” both come down to us from ancient words for

trees and tree bark. It is presumed that said bark was the surface for

early writings. “LIBR…”, from the Latin word liber meaning

“book,” in many languages is a prefix that indicates a bookseller’s

shop, while in English it has come to mean a collection of books and

from that also the room or building where books are kept. “BIBLIO…”

derives instead from the Greek biblion (one book) and biblia (books, plural). We get the word Bible through the Greek root, which leaked into old Latin and meant The Book.

Therefore it is no wonder that in the minds of many people, books = library. In fact, most libraries are large collections of books, but that does not mean that every large collection of books is a library. Amazon has a large number of books, but is not a library; it is a store where books are sold. Google has quite a few books in its "book search" and even allows you to view portions of the books without payment, but it is also not a library, it's a search engine. The Internet Archive, Amazon, and Google all have catalogs of metadata for the books they are offering, some of it taken from actual library catalogs, but a catalog does not make a quantity of books into a library. After all, Home Depot has a catalog, Walmart has a catalog; in essence, any business with an inventory has a catalog.

"...most libraries are large collections of books, but that does not mean that every large collection of books is a library."

The Library Test

First, I want to note that the Internet Archive has met the State of California test to be defined as a library, and this has made it possible for the Archive to apply for library-related grants for some of its projects. That is a Good Thing because it has surely strengthened the Archive and its activities. However, it must be said that the State of California requirements are pretty minimal, and seem to be limited to a non-profit organization making materials available to the general public without discrimination. There doesn't seem to be a distinction between "library" and "archive" in the state legal code, although librarians and archivists would not generally consider them easily lumped together as equivalent services.

The Collection

The Archive's

blog post says "the Internet Archive currently lends about as many as a US library that serves a population of about 30,000." As a comparison, I found in the statistics gathered by the

California State Library those of the Benicia Public Library in Benicia California. Benicia is a city with a population of 31,000; the library has about 88,000 books. Well, you might say, that's not as good as over one million books at the Internet Archive. But, here's the thing: those are not 88,000 random books, they are books chosen to be, as far as the librarians could know, the best books for that small city. If Benicia residents were, for example, primarily Chinese-speaking, the library would surely have many books in Chinese. If the city had a large number of young families then the children's section would get particular attention. The users of the Internet Archive's books are a self-selected (and currently un-defined) set of Internet users. Equally difficult to define is the collection that is available to them:

This library brings together all the books from Phillips Academy Andover and Marygrove College, and much of Trent University’s

collections, along with over a million other books donated from other

libraries to readers worldwide that are locked out of their libraries.

Each of these is (or was, in the case of Marygrove, which has closed) a collection tailored to the didactic needs of that institution. How one translates that, if one can, to the larger Internet population is unknown. That a collection has served a specific set of users does not mean that it can serve all users equally well. Then there is that other million books, which are a complete black box.

Library science

I've argued before against dumping a large and undistinguished set of books on a populace, regardless of the good intentions of those doing so. Why not give the library users of a small city these one million books? The main reason is the ability of the library to fulfill the

5 Laws of Library Science:

- Books are for use.

- Every reader his or her book.

- Every book its reader.

- Save the time of the reader.

- The library is a growing organism. [0]

The online collection of the Internet Archive nicely fulfills laws 1 and 5: the digital books are designed for use, and the library can grow somewhat indefinitely. The other three laws are unfortunately hindered by the somewhat haphazard nature of the set of books, combined with the lack of user services.

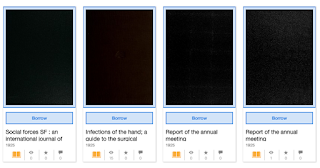

Of the goals of librarianship, matching readers to books is the most difficult. Let's start with law 3, "every book its reader." When you follow the URL to the National Emergency Library, you see something like this:

The lack of cover art is not the problem here. Look at what books you find: two meeting reports, one journal publication, and a book about hand surgery, all from 1925. Scroll down for a bit and you will find it hard to locate items that are less obscure than this, although undoubtedly there are some good reads in this collection. These are not the books whose readers will likely be found in our hypothetical small city. These are books that even some higher education institutions would probably choose not to have in their collections. While these make the total number of available books large, they may not make the total number of

useful books large. Winnowing this set to one or more (probably more) wheat-filled collections could greatly increase the usability of this set of books.

"While these make the total number of available books large, they may not make the total number of useful books large."

A large "anything goes" set of documents is a real challenge for laws 2 and 4:

every reader his or her book, and

save the time of the reader. The more chaff you have the harder it is for a library user to find the wheat they are seeking. The larger the collection the more of the burden is placed on the user to formulate a targeted search query and to have the background to know which items to skip over. The larger the retrieved set, the less likely that any user will scroll through the entire display to find the best book for their purposes. This is the case for any large library catalog, but these libraries have built their collection around a particular set of goals. Those goals matter. Goals are developed to address a number of factors, like:

- What are the topics of interest to my readers and my institution?

- How representative must my collection be in each topic area?

- What are the essential works in each topic area?

- What depth of coverage is needed for each topic? [1]

If we assume (and we absolutely must assume this) that the user entering the library is seeking information that he or she lacks, then we cannot expect users to approach the library as an expert in the topic being researched. Although anyone can type in a simple query, fewer can assess the validity and the scope of the results. A search on "California history" in the National Emergency Library yields some interesting-looking books, but are these the best books on the topic? Are any key titles missing? These are the questions that librarians answer when developing collections.

The creation of a well-rounded collection is a difficult task. There are actual measurements that can be run against library collections to determine if they have the coverage that can be expected compared to similar libraries. I don't know if any such statistical packages can look beyond quantitative measures to judge the quality of the collection; the ones I'm aware of look at call number ranges, not individual titles. There

Library Service

The Archive's

own documentation states that "The Internet Archive focuses on preservation and providing access to

digital cultural artifacts. For assistance with research or appraisal,

you are bound to find the information you seek elsewhere on the

internet." After which it advises people to get help through their local public library. Helping users find materials suited to their need is a key service provided by libraries. When I began working in libraries in the dark ages of the 1960's, users generally entered the library and went directly to the reference desk to state the question that brought them to the institution. This changed when catalogs went online and were searchable by keyword, but prior to then the catalog in a public library was primarily a tool for librarians to use when helping patrons. Still, libraries have real or virtual reference desks because users are not expected to have the knowledge of libraries or of topics that would allow them to function entirely on their own. And while this is true for libraries it is also true, perhaps even more so, for archives whose collections can be difficult to navigate without specialized information. Admitting that you give no help to users seeking materials makes the use of the term "library" ... unfortunate.

What is to be done?

There are undoubtedly a lot of useful materials among the digital books at the Internet Archive. However, someone needing materials has no idea whether they can expect to find what they need in this amalgamation. The burden of determining whether the Archive's collection might suit their needs is left entirely up to the members of this very fuzzy set called "Internet users." That the collection lends at the rate of a public library serving a population of 30,000 shows that it is most likely under-utilized. Because the nature of the collection is unknown one can't approach, say, a teacher of middle-school biology and say: "they've got what you need." Yet the Archive cannot implement a policy to complete areas of the collection unless it knows what it has as compared to known needs.

"... these warehouses of potentially readable text will remain under-utilized

until we can discover a way to make them useful in the ways that

libraries have proved to be useful."

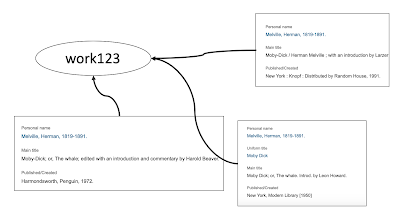

I wish I could say that a solution would be simple - but it would not. For example, it would be great to extract from this collection works that are commonly held in specific topic areas in small, medium and large libraries. The statistical packages that analyze library holdings all are, AFAIK, proprietary. (If anyone knows of an open source package that does this, please shout it out!) If would also be great to be able to connect library collections of analog books to their digital equivalents. That too is more complex than one would expect, and would have to be much simpler to be offered openly. [2]

While some organizations move forward with digitizing books and other hard copy materials, these warehouses of potentially readable text will remain under-utilized until we can discover a way to make them useful in the ways that libraries have proved to be useful. This will mean taking seriously what modern librarianship has developed over its circa 2 centuries, and in particular those 5 laws that give us a philosophy to guide our vision of service to the users of libraries.

-----

[0] Even if you are familiar with the 5 laws you may not know that Ranganathan was not as succinct as this short list may imply. The book in which he introduces these concepts is over 450 pages long, with extended definitions and many homey anecdotes and stories.

[1] A search on "collection development policy" will yield many pages of policies that you can peruse. To make this a "one click" here are a few *non-representative* policies that you can take a peek at:

[2]

Dan Scott and I did a project of this nature with a Bay Area public library and it took a huge amount of human intervention to determine whether the items matched were really "equivalent". That's a discussion for another time, but, man, books are more complicated than they appear.