a Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal, Division of Health Security and Emergencies, World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Manila, Philippines.

b Office of the WHO Representative in the Philipines, Sta Cruz, Manila, Philippines.

Correspondence to WPSAR@wpro.who.int).

To cite this article:

McPherson M, Counahan M. Responding to Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal, 2015, 6(Suppl 1):1–4. doi:10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.4.HYN_026

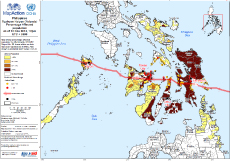

The Philippines is a disaster-prone country,1 ranked as the second highest country worldwide at risk of natural disasters.2 On 8 November 2013, Typhoon Haiyan (local name “Yolanda”) made landfall in the Philippines and had significant impact (Box 1).3 It is the strongest typhoon to have ever made landfall in the western North Pacific Ocean with a storm surge of 5–6 metres.4 Typhoon Haiyan left a corridor of destruction across the Philippines (Figure 1) that affected the lives of 16 million people, devastated a health system and challenged every sector of the country.3 Regions 6, 7 and 8 – Western, Central and Eastern Visayas – were the most affected (Figure 1).

As a result of Typhoon Haiyan, a national state of calamity was declared by the President of the Philippines on 11 November 2013, and the Inter-Agency Standing Committee rated it as a Level 3 emergency.5 For the first time, the World Health Organization (WHO) graded an event as a Level-3 emergency according to their Emergency Response Framework.6 The resulting response was immense, and involved both national and international support. The Health Cluster was co-led by the Philippines Department of Health (DOH) and the WHO Representative Office in the Philippines. Key efforts of the Health Cluster included:7

In this issue of the Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal, we provide a summary of the health response to Haiyan through 20 articles. As described in the brief report by Gocotano et al.,8 18 months after Haiyan, the WHO Representative Office in the Philippines and the DOH wanted to document the lessons learned from Haiyan. WPSAR was pleased to be involved with this project, as it matched with the aim of building capacity in communicating epidemiological and operational research within the WHO Western Pacific Region. It will hopefully contribute to reversing the trend of authors from outside disaster-affected countries publishing manuscripts about events.8

This Typhoon Haiyan issue starts with a perspective article about the transition period from response to recovery; it argues that the transition period for Haiyan occurred from three to seven months post-Haiyan and was an overlap of different activities among health sector responders.5

Following Haiyan, many existing health programmes in the Philippines required rebuilding, and in some cases, they were improved. The tuberculosis programme had to locate and facilitate treatment for existing patients and restore diagnostic capabilities; this was accomplished within two months.9 New guidelines for maternal and newborn care following emergencies and disasters were developed and used extensively, including implementing Kangaroo Mother Care in 15 health facilities.10 Increased coordination of services for people with disability improved beyond pre-Haiyan levels, demonstrating that it is possible to “build back better” after the response to a disaster.11 Health system recovery for noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) in Region 8 was based on the WHO Package of Essential Noncommunicable Disease Interventions and resulted in trained health service providers; availability of essential equipment, supplies and medicines; functional referral system; and use of monitoring tools.12

Several new initiatives were implemented during the response to Haiyan. Social media was used by WHO for the first time in the Philippines and was a key part of the risk communication strategy.13 Another first was the classification and registration form used for foreign medical teams which proved beneficial for coordination.14 A community-based alcohol intervention programme was piloted in Tacloban City and showed there was a problem with alcohol and introducing a programme to address it possible with minimal resources.15

There were three disease surveillance systems used during the response to Haiyan: Philippine Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (PIDSR), Event-based Surveillance and Response (ESR) and Surveillance in Post Extreme Emergencies and Disasters (SPEED). An assessment of when these systems were operational showed that the two routine systems (PIDSR and ESR) were disrupted only in Leyte province (Region 8), yet almost all areas delayed the activation of SPEED.16 Another assessment, conducted 16 months after Haiyan in Region 8 only, showed that the reestablishment of PIDSR was slow and not operating at pre-Haiyan levels.17 A third study analysed the data from SPEED for the three noncommunicable syndromes and found high blood pressure, acute asthma attacks and diabetes were of concern following Haiyan. This study also needed for future disaster response.18

Also in this issue, several field investigation reports provide a snapshot of different components of the health response to Haiyan. An assessment of evacuation centres conducted two weeks after Haiyan suggested a variation in the size of the evacuation centres and mixed levels of services.19 A team from DOH was involved in the management of the dead, which was challenging due to limited access to the affected areas.20 Water quality testing conducted in the early stages of the response was repeated after local governmental unit teams were trained in water testing, sanitary surveys, water treatment and water safety planning.21 Efforts for dengue prevention and control were multifaceted, and despite a multitude of potential breeding sites, there were no outbreaks reported.22 The work of the administrative team from the WHO Representative Office in the Philippines was unprecedented; they processed 22 times the annual budget, more than 100 international consultants were hired and the staff more than doubled.23

The response to Haiyan provided other key lessons for future responses. A case control study showed that not evacuating before the storm, despite official recommendations, was the greatest risk factor for dying during Typhoon Haiyan and that the use of the term “storm surge” to warn the public before Typhoon Haiyan was not understood.24 Medicine management during the response was difficult and was compounded by receiving donation of short-dated, near-expiry and unnecessary items which created additional burden on the health system.25 A small study of self-reported health costs suggested many people had catastrophic out-of-pocket health expenditures with consultation and transportation costs as the main barriers to health service utilization.26

This cross-section of articles provides many observations and lessons learnt from the health response to Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. We would like to highlight what we see as the three key lessons from the overall response. First, there were waves of health needs post-Haiyan, with risks for some communicable diseases (e.g. rabies, dengue and measles) extending through the recovery period and demands for NCDs, mental health and maternal health continuing for months after the official response period had ended. The second lesson was that data to support epidemiological and operational research during disaster response, although required, was often limited and improving essential data collection as part of disaster preparedness would help ensure critical operational research during disaster responses can be undertaken. Finally, we learnt national responders have a wealth of knowledge and experience that needs to be published. Support should be provided for capacity building to facilitate research and the publication of findings to help strengthen the collective response to emergencies.

We are grateful that we have had the opportunity to be part of capacity building of many first time authors in this issue of WPSAR. We would like to thank all the authors for their commitment and perseverance in getting their work published. We also encourage other first time authors to submit their experiences in responding to disasters to WPSAR.