a Office of the WHO Representative in the Philippines, Sta Cruz, Manila, Philippines.

b Region Office 8, Department of Health, Tacloban City, Leyte, Philippines.

Correspondence to Rammell Eric Martinez (emails: martinezra@wpro.who.int or rammell.martinez@gmail.com).

To cite this article:

Martinez RE et al. Use of the WHO Package of Essential Noncommunicable Disease Interventions after Typhoon Haiyan. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal, 2015, 6(Suppl 1):18–20. doi:10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.3.HYN_024

Typhoon Haiyan hit the Philippines on 8 November 2013 and caused mass destruction;1 health facilities were destroyed or not functioning and medical supplies were quickly exhausted. Afterwards, people with noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) were more vulnerable due to lack of health care access.2 This was also reported after the China earthquake where there were high morbidity and deaths from NCDs due to a lack of dialysis, chemotherapy and other medical support for those with an NCD.3

The World Health Organization (WHO) Package of Essential Noncommunicable Disease Interventions (PEN) is a “prioritized set of cost-effective interventions that can be delivered to an acceptable quality of care even in resource-poor settings”. These interventions are the minimum standards needed to integrate and advance care of NCDs in primary health care as well as in ensuring equity in providing health care and achieving universal coverage of health reforms.4

The PEN approach was adopted by the Philippine Department of Health (DOH) for nationwide implementation;5 however, implementation was slow due to logistical and manpower issues. After Haiyan, PEN implementation in primary health care facilities became a priority, with Region 8 chosen as a pilot site for using PEN implementation for health system recovery post-disaster. This brief report describes the implementation of two of the four PEN protocols in Region 8 – Protocol 1 on managing and preventing heart attack, stroke and renal disease and Protocol 2 on health education and promotion and smoking cessation.

The key areas for PEN implementation included using the PEN approach to restore service delivery and management in primary health care facilities in Region 8, training health workers on PEN implementation and providing required materials and PEN implementation tools. Monitoring visits that included supportive supervision were also conducted in primary health care facilities in six provinces in Region 8. These assessed the use of the PEN protocols, availability of PEN implementation tools and whether the implementation targets for Region 8 had been met.

From August 2014 to March 2015, 865 health representatives, health managers, service providers and implementers in primary health care facilities, as well as at the regional and provincial health offices, were trained on PEN implementation. Training was conducted for all primary health care facilities in the six provinces of Region 8; this comprised all 143 cities and municipalities (100%).

During the same period, NCD equipment and supplies were provided to all primary health care facilities (100%) in all six provinces and 143 cities/municipalities in Region 8. This included 144 rural health units, 21 district health centres, 28 district hospitals, three diabetic clinics, six provincial health offices, six provincial DOH offices and one NCD unit. Materials included 424 sets of blood pressure measuring devices, 424 units of glucose, cholesterol and uric acid (GCU) meters, 788 packs of lancets, 488 canisters (12 200 pieces) of blood glucose strips and 480 canisters (4800 pieces) of blood cholesterol strips.

Adequate materials for the implementation of PEN were also distributed, including NCD risk assessment forms, target client assessment logbooks, cardiovascular disease risk registry logbooks, risk prediction charts, copies of the PEN protocol algorithm and PEN pocket booklets.

Primary health care facilities were randomly selected from the National Health Facility Registry for monitoring visits and supportive supervision over two time periods – November to December 2014 and February to March 2015. Six of 25 (24%) monitored primary health care facilities had started implementing PEN during the first round, and 17 of 27 (63%) had started implementing PEN during the second round. Overall, 10 of the 52 (19%) primary health care facilities reported they had essential medicines “always available” (Table 1).

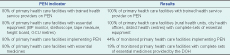

PEN, Package of Essential Noncommunicable Disease Interventions.

After six months, two of the four PEN indicators had been met in Region 8: all primary health care facilities had trained health service providers and complete sets of essential equipment (Table 2). The other two indicators had not been met as only 19% of monitored primary health care facilities had complete sets of essential medicines provided by the DOH and only 44% were implementing PEN where the target for each was 80%.

BP, blood pressure; DOH, Department of Health; GCU, glucose cholesterol uric acid; and PEN, Package of Essential Noncommunicable Disease Interventions.

PEN implementation in Region 8 after Haiyan has resulted in trained health service providers; availability of essential equipment, supplies and medicines; functional referral systems; and use of monitoring tools.

The built-in mechanisms of PEN should ensure its sustainability. To further support this, a sustainability plan was developed that included having a NCD Coordinator/PEN Focal Person and Programme Manager at the DOH Office in Region 8 who will be responsible for conducting monitoring activities and supportive supervision. The PEN protocols have also been included in the new local government unit score card and in PhilHealth’s Tsekap Benefit Package. Including a budget allocation in annual plans and having a manual of operations for PEN will also assist with sustainability.

This pilot project was conducted by government-operated health facilities, i.e. community health stations and rural health units. Therefore, other primary health care facilities such as hospital outpatient clinics and private clinics were not included.

This institutionalization of PEN in Region 8 of the Philippines, which was a priority after Haiyan, shows that the PEN programme is useful for restoring service delivery and management for NCDs in primary health care facilities post-disaster.

None declared.

WHO Representative Office in the Philippines.

We acknowledge our partners from the NCD unit at the Department of Health Regional Office 8 with special mention to Dr Ma Sol Villones and Ms Mae Analyne Marquez. We also thank those who helped during the trainings: Ms Winnie Grace Dorego, Ms Krystel Charisse Daya, Ms Rani Socorro Pastor, Dr Theresa Caidic, Dr Antonio Ida, Dr Laarni Dacuno and Ms Josephine de la Fuentes. Thanks also to the local government unit artners: Ms Purificacion Nuevo and Mr Cristobal Dexter Mendiola III.

We also thank the two WHO consultants who provide technical input in PEN implementation in Region 8: Dr Francisca Cuevas and Dr Ronald Flores. Special thanks also to the WHO Representative Office in the Philippines.