a Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of the Philippines, Philippine General Hospital, Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines.

b Office of the WHO Representative in the Philippines, Sta Cruz, Manila, Philippines.

Correspondence to Lester Sam Geroy (email: lelim22@yahoo.com).

To cite this article:

Espallardo N et al. A snapshot of catastrophic post-disaster health expenses post-Haiyan. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal, 2015, 6(Suppl 1):76–81. doi:10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.2.HYN_017

Introduction: This paper provides a snapshot of the health-care costs, out-of-pocket expenditures and available safety nets post-Typhoon Haiyan.

Methods: This descriptive study used a survey and document review to report direct and indirect health-care costs and existing financial protection mechanisms used by households in two municipalities in the Philippines at one week and at seven months post-Haiyan.

Results: Reported out-of-pocket health-care expenses were high immediately after the disaster and increased after seven months. The mean reported out-of-pocket expenses were higher than the reported average household income (US$ 24 to US$ 59).

Discussion: The existing local and national mechanisms for health financing were promising and should be strengthened to reduce out-of-pocket expenses and protect people from catastrophic expenditures. Longer-term mechanisms are needed to ensure financial protection, especially among the poorest, beyond three months when most free services and medicines have ended. Preparedness should include prior registration of households that would ensure protection when a disaster comes.

The Philippines is working towards universal health coverage (UHC), aiming to achieve equity of access to health care without its population suffering financial hardship. The country has a well-distributed public health care system that primarily serves low- and middle- income people, especially in rural areas. A strong private sector focused in urban areas primarily serves middle- and upper-income population.

The Philippine Health Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth) is the Philippines’ social health insurance agency, and it currently provides coverage for inpatient and a few public health interventions, e.g. newborn screening, perinatal mother and child care and tuberculosis. Efforts in the last five years have increased PhilHealth enrolment coverage from 62% in 2010 to 83% in 2014.1,2 A point-of-care enrolment policy was created in 2013 whereby eligible individuals are made automatic beneficiaries at the point of access to the health care system. A no-balance-billing policy, also created in 2013, mandates that no other fees be charged or paid by eligible patients in hospitals, aiming to reduce out-of-pocket expenses. Currently, these policies only apply to the poor and vulnerable identified by the Department of Social Welfare and Development or by the hospitals’ social welfare offices.3

Disasters and emergencies, such as Typhoon Haiyan that struck the central Philippines in November 2013, increase poverty and the vulnerability of the poor.4 High out-of-pocket expenses for health care post-disaster can lead to poverty as observed in the Philippines.5,6 Poverty incidence among families in Region 8 where Haiyan had the greatest impact was already 37% (2012).7 The government had previously established provisions to strengthen social services to protect people from financial risk in emergencies. The Republic Act 8185 mandated that local governments allocate 5% of their internal revenue to a Calamity Fund to be used when a local or national state of calamity is declared. After Typhoon Haiyan, PhilHealth declared it would subsidize the health-care costs of typhoon-affected individuals (PhilHealth Circular Nos. 0034–2013 and 0006–2014).8–10 PhilHealth also allowed delivery of hospital reimbursements in advance of claims to enable rebuilding and rehabilitating health facilities (PhilHealth Circular Nos. 0004–2014 and 0024–2014).11,12

Disaster literature on health needs, operations and service delivery are abundant; publications on out-of-pocket payments, financial risk protection and catastrophic health expenditures are also available. But there is a paucity of literature on health financing and financial risk protection in disaster and emergency settings and longer-term sustainable health financing efforts.

This paper provides a snapshot of the health-care costs, out-of-pocket expenses and available safety nets post-Haiyan, raising their potential impact as catastrophic health expenditure. Costs and out-of-pocket expenses were examined during the response phase (one week after) and the transition to the recovery phase (seven months after). Costs and out-of-pocket expenses reflect supply- and demand-side realities, e.g. availability of health services and safety nets.

This descriptive study used interviews and reviews of hospital and PhilHealth documents to gather data on financial barriers to health care, direct and indirect health-care costs and existing financial protection mechanisms used by individuals. Data gathering was conducted from 1 October to 30 November 2014 for information that covered the period of November 2013 (one week after Haiyan) and June 2014 (seven months after). The two study sites – Sta Fe, Leyte, and Guiuan, Eastern Samar – were purposely selected for their economic status, access to PhilHealth-accredited health facilities and the presence of local and international aid.

Household interviews were conducted with 35 community respondents selected by purposive sampling, i.e. individuals who visited health centres and hospitals. Our interviews aimed to identify (1) potential barriers to using health services; (2) actual health-care costs such as for laboratory tests, medicines and professional fees after PhilHealth benefits had been deducted; and (3) benefits from PhilHealth, conditional cash transfers and other safety nets applied post-Haiyan. The respondents were categorized into two groups based on their monthly income: (1) less than or (2) more than US$ 94 per month. We reviewed hospital and PhilHealth data on claims and costs of health services, including professional fees, laboratories and medicines to validate the results.

Direct health-care costs were defined as the costs of labour, supplies, medicines and equipment to provide patient-care services. Indirect health-care costs included non-medical components of obtaining health care including transportation, lodging and home services. Once a household’s financial health-care contribution exceeded 40%, after subsistence needs had been met, it was considered a catastrophic health expenditure.13

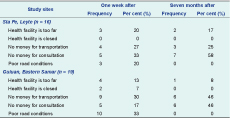

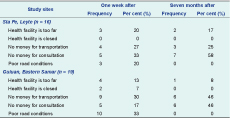

Availability of funds for consultation and transportation were the main barriers to seeking health services. One week after Haiyan, 23 of 35 respondents (66%) reported they had no money for transportation or medical consultations (Table 1).

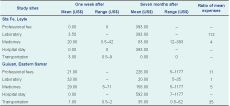

The monthly family income in the study sites ranged from US$ 24 to US$ 59. The reported health-care costs one week post-Hiayan ranged from zero, when free services were available, to that which exceeded monthly incomes, particularly for laboratory and medicines costs, even after PhilHealth subsidies and benefits were applied (Table 2). Financial barriers during the immediate phase were further aggravated by difficulty to access cash either from others, who also did not have cash; from local government; or from local banks.

* All figures in US$ at exchange rate of US$ 1.00 = PhP 42.47 (2 June 2014). Values without range represent those with only one respondent.

In public health facilities, there was minimal out-of-pocket payment because of the no-balance-billing policy of PhilHealth. However, patients still had to purchase medicines and supplies if these were not available in these facilities. Records confirmed out-of-pocket payments ranged between US$ 3 and US$ 21 for medicines. Similarly, in private health facilities in Guiuan, patients had to pay the excess amount outside PhilHealth coverage which ranged from US$ 11 to US$ 21.

Seven months after the emergency, the reported costs of health care had increased. These were highest for professional fees in Sta Fe and hospital stays in Guiuan (US$ 393 and US$ 592, respectively). Overall, higher out-of-pocket expenses were found in Sta Fe compared with Guiuan. Mean health-care costs, except laboratory and transportation, were higher than the average household income (US$ 24 to US$ 59), which suggests it was catastrophic health expenditure. One respondent had a major surgical procedure (US$ 1361). Review of hospital records and PhilHealth reimbursements seven months after the typhoon confirmed the high costs.

Community insurance was the main source of financial assistance for health care (16/35 respondents, 46%). Other sources were local government funds (9/35, 26%), PhilHealth reimbursement (8/35, 23%) and conditional cash transfer remittance (2/35, 6%). Households also reported borrowing necessary funds from relatives and local cooperatives. Financial assistance from local governments was usually granted upon request from authorities. There were no reports of blanket cash relief for affected households.

Among the 35 respondents, 20 were in the category earning an average monthly income of less than US$ 94, and 15 were in the group earning more than US$ 94. Both groups self-reported similar proportions of PhilHealth membership (25–27%). A higher proportion of the poorest were registered under the National Household Targeting System for Poverty Reduction programme. However, the poorest received less support from local governments (30% versus 67%), and they had more out-of-pocket expenses, especially seven months after the typhoon (55% versus 47%) (Table 3).

* US$ 94.00 cut off is based on minimum monthly income levels in Region 8 from the Department of Labour and Employment.

LGU, local government unit; NHTS, National Household Targeting System for Poverty Reduction; OOP, out-of-pocket; and 4Ps, Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program.

This study showed that the self-reported costs of health care post-Haiyan were high with consultation and transportation costs as the main barriers to health service utilization. Out-of-pocket expenses, after PhilHealth benefits were deducted, particularly for professional fees and hospital stays, were alarming. Because of the no-balance-billing policy, respondents using public facilities reported no costs; hence, out-of-pocket expenses and costs represented private hospital services.

These high costs suggest catastrophic health expenditures. Another survey in Region 8 of 2766 postpartum women 11–13 months post-Haiyan showed that both public and private prenatal care had an average cost of US$ 4 (range: US$ 0 to US$ 149), while the average cost of delivery was US$ 73 (range: US$ 0 to US$ 2191).14 Families with the reported average monthly income of US$ 24 would be adversely affected by these health-care costs. Interestingly, official sources reported a higher average income in Region 8 than was reported in this study (US$ 314 monthly in 2009).7

We observed that out-of-pocket expenses increased over the seven months after Haiyan. Within one week, health services were available in public facilities (e.g. Rural Health Units) as well as being provided by local or international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). Essential medicines, when available, were also provided free of charge. This may explain why the reported out-of-pocket payments for professional fees and medicines were low at this time. By seven months, all hospitals and primary care facilities in the two study areas were back in operation, roads were repaired making travel easier and more cash was in circulation. However, most international and local NGOs had left along with their free medicines.

Community insurance was the most accessed source of health financing at the local level in this study. Local government funds were not significant sources of support and were commonly only accessed through direct request from government officials. This was confirmed by another study where only 11–17% of households in Region 8 reported seeking assistance from the government, while 8–14% sought private assistance (NGO, charity, individuals or groups).15 There was no information on how the local calamity funds were being spent, what proportion was earmarked for health or whether they were distributed as relief fund to local residents.

If the government is to be the main source of social safety nets post-disaster, mechanisms for implementation as well as the amount of investment required to mitigate catastrophic health expenditures need to be determined. The Philippines does not yet have updated or localized costing on how much capitalization or investment is needed. This is closely linked to determining the amount required for blanket cash relief for health if the country (or any donor) wanted to use this mechanism post-disaster. Both supply and demand interventions should be considered to enhance social safety nets for health post-emergency.

New initiatives for UHC include expansion of PhilHealth enrolment through point-of-care and no-balance-billing policies, expansion of primary care benefits subsidized by PhilHealth, price regulation for case-based payments, upgrading of health facilities, augmenting the health workforce (doctors, nurses and midwives) in rural and isolated areas and enhancing the availability of medicines and reducing their cost. There is optimism that the country is on the right path. Current data from 2008 to 2013 demonstrate the distribution of health insurance is becoming more pro-poor.16,17 However, findings from our study did not show preferential benefits of safety nets to the poorest. The government has increased its revenue for health through sin taxes, allowing it to subsidize 14.7 million new members.18

This descriptive study identified the patterns of costs, out-of-pocket expenses and safety nets during the response and the transition to recovery post-Haiyan. Limitations include a small sample size, reliance on self-reporting, recall bias as the survey was conducted seven months post-event, lost records and data gaps. No actual calculation of local health accounts was done. There was also no investigation on whether the costs were actually paid for from private funds or from government relief.

When the next disaster hits the Philippines, people should not incur out-of-pocket payments for health care. Financial risk protection should be mainstreamed into preparedness, risk assessment, mitigation, planning, response and recovery plans. National and local policies and mechanisms for financial protection should clearly benefit the poorest. Knowledge gaps in health-care financing in disasters include demand questions (e.g. rate of impoverishment because of health care post-disasters) and supply questions (e.g. disaster subsidies/loans for private hospitals). The health system will need to focus on supply mechanisms to ensure the availability of health services and medicines at no or minimal cost with safety nets for the poorest households. Longer-term mechanisms are needed to ensure financial protection especially for the poorest beyond three months when the bulk of free services and medicines being provided by international responders end. Preparedness should include an intensive drive to enrol households in social health insurance or other mechanisms to ensure protection when the next disaster comes.

None declared.

None.

We thank the staff of the hospitals and PhilHealth offices in Sta Fe, Leyte and Guiuan, Eastern Samar for granting interviews and review of PhilHealth documents.