a Emerging Disease Surveillance and Response Unit, Division of Health Security and Emergencies, World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Manila, Philippines.

Correspondence to Frank Konings (e-mail: koningsf@wpro.who.int).

To cite this article:

Squires RC, Konings F. Preparedness for molecular testing for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus among laboratories in the World Health Organization Western Pacific Region. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal, 2014, 5(3). doi:10.5365/wpsar.2014.5.3.001

Since the notification of the first cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in September 2012, a total of 837 laboratory-confirmed cases and 291 deaths have been reported globally as of 23 July 2014,1 primarily in the Arabian Peninsula. However, the possibility of importation of MERS-CoV in the World Health Organization (WHO) Western Pacific Region exists given the large number of individuals who travel annually to the Middle East for religious purposes, employment or other reasons. Malaysia2 and the Philippines3 have recently reported cases in people travelling from the Middle East. As such, it is essential that laboratory capacity be in place for the detection of MERS-CoV.

Several laboratories worldwide established molecular detection of MERS-CoV by reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) early in the outbreak. WHO encouraged these laboratories to provide technical support and reference testing service to countries without such capacity while expanding MERS-CoV testing at the national level by building primarily on the existing molecular testing capacity of the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS). Serological assays for MERS-CoV have also been developed, but they are not widely available and have not been fully validated; case confirmation has relied predominantly on molecular detection methods.

We present the findings of a voluntary, rapid survey targeting national-level public health laboratories in the Western Pacific Region. The survey was administered after nearly two years of activities aimed at building laboratory capacity for MERS-CoV detection and sought to determine preparedness of countries for MERS-CoV testing. Questions addressed three main areas: availability of protocols, guidance and reagents; immediate testing capacity; and referral mechanisms.

The survey was web-based, consisted of 21 multiple-choice questions and was conducted between 18 June and 14 July 2014. Participating laboratories were assured of confidentiality and the reproduction of aggregated data alone in publications. A total of 21 survey invitations were distributed to 18 countries and areas (areas4 are non-sovereign jurisdictions within a WHO region, such as the French overseas collectivities of New Caledonia and French Polynesia; countries and areas are together referred to as “countries” in this article). Invitations principally targeted one responsible laboratory in each country; for three countries, two laboratories were included as they were both tasked with MERS-CoV testing. Survey responses were not verified for accuracy.

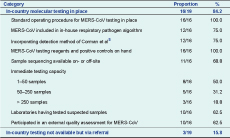

Results are illustrated in Table 1. The survey was completed by 19 laboratories in 16 countries of the Western Pacific Region. The majority of participating laboratories (15/19) were National Influenza Centres (NICs) or located within an institution housing an NIC, highlighting the role of the pre-existing GISRS network in MERS-CoV testing.

* Laboratories participating in the survey were located in: Australia, Cambodia (two laboratories), Fiji, French Polynesia, Hong Kong (China), Japan, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia (two laboratories), Mongolia, New Caledonia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, the Republic of Korea, Singapore and Viet Nam (two laboratories).

Sixteen (84.2%) laboratories in 13 countries indicated that they had capacity in place for molecular detection of MERS-CoV, while three laboratories used referral mechanisms instead. All 16 laboratories with MERS-CoV testing capacity responded that they had a standard operating procedure for molecular detection of MERS-CoV in place, with 12 choosing to incorporate MERS-CoV into their standard algorithm for respiratory pathogens. All 16 reported having the appropriate positive control material, primers and probes for MERS-CoV RT–PCR on hand. Most laboratories (12/16) used or adapted the recommended RT–PCR protocol for screening and confirmation designed by Corman et al.5 Sequencing, as a means of confirming discordant results and providing insight into the origin, spread and possible mutation of the virus, was equally available in on- or off-site facilities in 11 laboratories. Ten laboratories (in 10 countries) reported having participated in an external quality assessment (EQA) for MERS-CoV testing; most (8/10) used the EQA organized by the Robert Koch Institute in Germany. All 16 laboratories followed, or incorporated as part of their own design, the WHO interim recommendations for MERS-CoV testing6 and interim guidelines for laboratory biorisk management.7

At the time of the survey, 10 laboratories in nine Western Pacific Region countries had already tested suspected samples of MERS-CoV, indicating the importance of testing capacity in the Region even though the virus thus far primarily affects countries outside the Region. To determine each laboratory’s emergency outbreak capacity, participants were also asked to estimate the volume of suspected MERS-CoV samples that could be processed in 48 hours. Of the 16 laboratories with MERS-CoV testing capacity, three (18.8%) indicated they could test over 250 samples, five (31.2%) could test 50–250 samples and eight (50%) could test 1–50 samples. Two-thirds (11) of these laboratories maintained that they could report to public health authorities within one day of obtaining results; the remainder could report in 2–5 days.

Referral is an important mechanism for pathogen identification and confirmation. Of the 19 laboratories participating in the survey, five (two in low-income and three in high-income countries)8 had no mechanism for international referral of MERS-CoV samples. The absence of referral in the three high-income countries may indicate strong confidence in domestic expertise to confirm and identify pathogens. Most laboratories (17/19) reported having one or more staff certified by the International Air Transport Association (IATA) to ship infectious material abroad; the majority (73.7%) reported having more than one such staff.

The findings of this survey revealed good regional laboratory coverage in the Western Pacific Region for molecular detection of MERS-CoV, primarily through the GISRS laboratory network, nearly two years after the first reported MERS-CoV case in the Middle East. All countries indicated that they had national-level laboratories with the necessary materials for MERS-CoV testing on-site or employed international referral. It is important to continue strengthening the apparatus for MERS-CoV detection in the Region, in particular ensuring testing proficiency by EQA participation, and enhancing referral mechanisms and IATA certification where needed. National-level capacity is a key asset provided that it is well connected with the public health system at the subnational level. In-country referral capacity must therefore also be in place. WHO and its partners will continue to provide technical support to countries to address these issues. In conclusion, while there proved to be sufficient time to build laboratory capacity for the detection of MERS-CoV before its entry into the Western Pacific Region, we may not be so fortunate for future emerging infectious diseases. Thus, maintaining and further strengthening the public health laboratory system is a critical undertaking.

None.

None declared.

The authors are grateful to the participating laboratories and countries that shared their information and took the time to complete the survey. We would also like to thank Sarah Hamid for critical reading of the manuscript.