a WHO National Influenza Centre, Institute of Environmental Science & Research, National Centre for Biosecurity & Infectious Disease, New Zealand.

Correspondence to Richard J Hall (e-mail: richard.hall@esr.cri.nz).

To cite this article:

Hall R et al. Tracking oseltamivir-resistance in New Zealand influenza viruses during a medicine reclassification in 2007, a resistant-virus importation in 2008 and the 2009 pandemic. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal, 2012, 3(4). doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2012.3.3.002

Introduction: Oseltamivir (Tamiflu®) is an important pharmaceutical intervention against the influenza virus. The importance of surveillance for resistance to oseltamivir has been highlighted by two global events: the emergence of an oseltamivir-resistant seasonal influenza A(H1N1) virus in 2008, and emergence of the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus in 2009. Oseltamivir is a prescription medicine in New Zealand, but more timely access has been provided since 2007 by allowing pharmacies to directly dispense oseltamivir to patients with influenza-like illness.

Objective: To determine the frequency of oseltamivir-resistance in the context of a medicine reclassification in 2007, the importation of an oseltamivir-resistant seasonal influenza virus in 2008, and the emergence of a pandemic in 2009.

Methods: A total of 1795 influenza viruses were tested for oseltamivir-resistance using a fluorometric neuraminidase inhibition assay. Viruses were collected as part of a sentinel influenza surveillance programme between the years 2006 and 2010.

Results: All influenza B, influenza A(H3N2) and influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses tested between 2006 and 2010 were shown to be sensitive to oseltamivir. Seasonal influenza A(H1N1) viruses from 2008 and 2009 were resistant to oseltamivir. Sequencing of the neuraminidase gene showed that the resistant viruses contained an H275Y mutation, and S247N was also identified in the neuraminidase gene of one seasonal influenza A(H1N1) virus that exhibited enhanced resistance.

Discussion: No evidence was found to suggest that increased access to oseltamivir has promoted resistance. A probable importation event was documented for the global 2008 oseltamivir-resistant seasonal A(H1N1) virus nine months after it was first reported in Europe in January 2008.

Over the last decade there has been an extensive amount of research into the development and occurrence of antiviral drug resistance in human influenza viruses.1 An effective class of anti-influenza drugs known as neuraminidase inhibitors have been developed which include the drug oseltamivir phosphate (Tamiflu®). Neuraminidase inhibitors block the release of progeny virions from a host cell by selectively binding to the active site of the neuraminidase enzyme. This inhibits cleavage of the sialyl-acid bond to the host receptor, thus the virus is unable to be released from infected host cells and spread to new cells.2 Clinical trials of oseltamivir have shown reduced symptom severity and a reduction in the duration of the illness.3–5 Oseltamivir is reported to be widely used, with 65 million treatment courses prescribed worldwide.6 Oseltamivir-resistance in influenza should be closely monitored to determine if the continued efficacy of oseltamivir warrants its use for influenza.7 Such work not only determines the present efficacy of the drug but also reveals important information on the genesis of anti-viral drug resistance in influenza viruses.

In New Zealand, oseltamivir is a prescription medicine that is most effective if administered within the first 48 hours of infection. In 2007, to increase availability of oseltamivir and reduce delays in obtaining a prescription of oseltamivir from a medical doctor, pharmacists were allowed to directly provide oseltamivir during the winter influenza season (April to November inclusive). The pharmacist had to be satisfied that the oseltamivir was for a resident of New Zealand, aged 12 years or more and presenting with the symptoms of influenza.8 This allowance was made with an expectation that influenza viruses from the community would be monitored for the potential development of oseltamivir-resistance.9

Preceding the 2007/2008 northern hemisphere season, instances of oseltamivir-resistance occurred at low levels in seasonal human influenza viruses.10 Increased occurrence of resistance in influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses has been detected in community samples in the United Kingdom,11 and sustained community transmission has been reported in Australia.12 Resistance has been shown to be caused by a number of mutations, particularly the His275Tyr (N1 numbering; herein referred to as H275Y) of the neuraminidase (NA) gene in influenza A(H1N1) viruses.13 In the winter of 2007/2008, a relatively high incidence of resistant seasonal A(H1N1) influenza viruses was detected in Europe (average ~20%).14,15 These resistant viruses, which were shown to carry an H275Y mutation, were subsequently reported in many other regions of the world.16–18

In this study we monitored the frequency of oseltamivir-resistance in influenza viruses circulating in New Zealand between 2006 and 2010. This surveillance was performed during a series of events that had the potential to alter the resistance profiles of circulating influenza viruses, including a change in the availability of oseltamivir at pharmacies in 2007, the importation of oseltamivir-resistant seasonal influenza viruses in 2008, and the emergence of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09. We discuss these findings in relation to the genesis of antiviral drug resistance in New Zealand, the importance of surveillance and in relation to findings overseas.

Clinical samples were collected in New Zealand as part of the national influenza sentinel surveillance programme, which has been previously described.19,20 Briefly, samples were collected weekly from general medical practice patients presenting with influenza-like illness, defined as an acute respiratory tract infection characterized by the abrupt onset of at least two of the following: fever, chills, headache and myalgia. Nasopharyngeal swabs or throat swabs were taken from patients and transported to the laboratory in viral transport media. Samples from 2006 to 2008 were obtained during the winter influenza season from May to September. Samples from 2009 and 2010 were obtained over the entire year as influenza surveillance was extended due to the pandemic.21 Additional clinical samples were obtained from hospital diagnostic laboratories in New Zealand throughout the course of each year as part of a reference testing service. These hospitals were located in Auckland, Waikato, Christchurch and Dunedin.

Diagnosis of influenza virus was made either by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) (method developed by Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia; World Health Organization [WHO] recommended), or viral culture followed by a haemagglutination/haemagglutination-inhibition assay using WHO reference antisera.

Influenza viruses from 2006 to 2008 were grown in cultured Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) cells in serum-free M199 media in the presence of TPCK-trypsin. Influenza viruses from 2009 were also grown in the cultured MDCK-SIAT1 cell line in DMEM:F12 media in the presence of TPCK-trypsin.22

The viral RNA was extracted directly from the clinical specimen using the Zymo viral RNA extraction kit (Zymo Research, Irvine California, United States of America; cat# R1034). The entire NA gene was amplified using universal NA influenza primers26 and the same primers were used for direct sequencing by the Sanger method (Big Dye Terminator v.3.1 cycle sequencing kit, Applied Biosystems, Nieuwerkerk, NL) on a capillary sequencer (Model 3100 Avant, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, United States of America).

Sales data for oseltamivir in 2004 and 2007 was provided courtesy of Roche Pharmaceuticals. Data include both prescription and pharmacy-exemption sales.

Samples were obtained as part of public health surveillance. Clinical conduct was consistent with the New Zealand Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights.

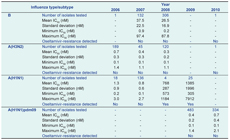

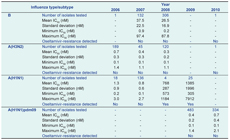

A total of 1795 influenza samples collected in New Zealand between 2006 and 2010 were tested for sensitivity to oseltamivir by fluorometric neuraminidase inhibition assay (Figure 1, Table 1).

* IC50 – inhibitory concentration of the drug at which a 50% reduction in enzymatic activity is observed.

* IC50 – inhibitory concentration of the drug at which a 50% reduction in enzymatic activity is observed.

† Boxes indicate the first, second and third quartiles and the whiskers are calculated as 1.5 times the interquartile distance. Outliers beyond this distance are plotted individually as (•), and the mean for each data set is indicated by the symbol (+). The thick dashed line represents the threshold at which viruses are determined to be resistant to oseltamivir. This threshold is 10-fold higher than the mean IC50 value for all years, calculated for each subtype. The calculation of the mean IC50 value threshold does not include 2008 and 2009 seasonal influenza A(H1N1) viruses, as all viruses in these years were resistant to oseltamivir. The thin dashed line shows the log10 IC50 zero axis.

All 521 influenza A viruses and all 133 influenza B viruses from 2006 and 2007 were shown to be sensitive to oseltamivir. In 2008, 306 influenza B and 120 influenza A(H3N2) viruses were found to be sensitive to oseltamivir. However, all four seasonal influenza A(H1N1) viruses isolated in this year were resistant to oseltamivir with IC50 values between 573 nM and 1184 nM (Figure 1, Table 1). Full-length sequencing of the NA gene for two of these viruses (sequence coverage of nucleotides 21–1413 and 22–940) revealed the presence of the H275Y mutation, with the sequenced region having almost complete identity (99% and 100% respectively) to the 2008 resistant-type viruses that had been reported from Europe earlier in the year [GenBank Accession: EU566977; A/Pennsylvania/02/2008(H1N1)]. Only a single nucleotide difference was observed (substitution E268D; G/T nucleotide 804; N1 subtype numbering).

As we have previously reported,27 all 2009 seasonal A(H1N1) viruses tested for sensitivity to oseltamivir were resistant (n = 25; Figure 1; Table 1), with IC50 values between 305 nM and 7912 nM.27 All were also shown to contain the H275Y mutation by RFLP analysis or by sequencing. Further sequencing of the NA gene of the 7912 nM virus (A/Wellington/31/2009), one of the three seasonal influenza A(H1N1) viruses with extremely high IC50 values of 5334 nM, 6370 nM and 7912 nM in this study (Figure 1), identified an additional significant mutation S247N (N1 numbering), as well as H275Y (GenBank accession KC117387).

All influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses tested in this study from 2009 and 2010 were shown to be sensitive to oseltamivir (Figure 1, Table 1) and sequencing of the NA gene for 11 of these viruses found that none carried the H275Y mutation.

Oseltamivir sales data in New Zealand for 2004 and 2007 showed a 4.5-fold increase in usage with 373 doses sold in 2004 compared to 1678 doses sold in 2007 (Figure 2). The greatest difference between 2004 and 2007 was in week 34 with 161 more units of oseltamivir sold in 2007 compared to 2004. As the population of New Zealand is 4.5 million, this increase in usage represents only an extremely small proportion of the total population.

This study shows that antiviral drug resistance to oseltamivir between 2006 and 2010 occurred at a very low level for most human influenza viruses in New Zealand. The exceptions to this observation were the seasonal A(H1N1) viruses from January 2008 onward, which showed high levels of resistance. This virus appears to have arrived in New Zealand (a southern hemisphere country) during the winter influenza season, nine months after its emergence was first reported in Europe.14,15 Other southern hemisphere countries such as Australia, South Africa and South America also reported the emergence of oseltamivir-resistant seasonal influenza viruses late in 2008.17,28 The resistant-type seasonal A(H1N1) became the predominant influenza virus in the first half of the New Zealand 2009 influenza season, showing that this virus is capable of both sustained transmission in the community and maintaining resistance to oseltamivir.29 Interestingly, we also note the occurrence of three of these seasonal A(H1N1) viruses with extremely high resistance to oseltamivir, brought about by the dual mutations S247N+H275Y. The S247N mutation reportedly reduces sensitivity to oseltamivir in seasonal A(H1N1) viruses30 and influenza A(H5N1) viruses31 and is known to cause extreme resistance to oseltamivir in influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses in combination with H275Y.32 Our results indicate that the presence of the dual S247N+H275Y mutation is likely to have a similar effect in seasonal A(H1N1) viruses.

Before 2008, we observed no oseltamivir-resistance for any influenza type/subtype in New Zealand. This is despite the regulatory change for oseltamivir in New Zealand in 2007, where it could be prescribed by pharmacists to patients presenting with influenza-like illness during the winter influenza season.8 A similar system was established in the United Kingdom where accredited pharmacists were able to supply oseltamivir to at-risk individuals during influenza outbreaks.33 Increased public access to the drug raises the potential for drug resistance due to selective pressure on the virus in individual patients undergoing treatment.34 However, since no substantial increase in usage in New Zealand was observed between 2004 and 2007, we cannot speculate what impact the medicine reclassification had on oseltamivir resistance. A comparative study in Japan, where oseltamivir is more widely used, reported no significant effect on the occurrence of resistance.35

Oseltamivir is important for controlling the transmission and dissemination of pandemic viruses before a vaccine becomes widely available. No vaccine was available in New Zealand until one year after the first cases of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 arose. This study shows that 100% of 817 influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses from 2009 and 2010 were sensitive to oseltamivir. During the early phases of the pandemic, New Zealand health authorities deployed a percentage of the pandemic stockpile of oseltamivir (< 50 000 doses; Ministry of Health, New Zealand Government), which likely assisted in the initial containment of the pandemic. It took approximately six to seven weeks from the first reported New Zealand cases on 26 April 2010 to the declaration of management phase in June 2010 when the virus had established community transmission. Previous epidemiological modelling studies have suggested that increased usage of oseltamivir during a pandemic may trigger the development of resistant viruses with no reduction in fitness to the virus.36,37 The levels of oseltamivir used in New Zealand are unlikely to have approached thresholds developed in these modelling studies, but our data show that oseltamivir-resistance in influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses remained low despite the issuance of pandemic stockpiles of oseltamivir.

Continued surveillance for anti-viral drug resistance in influenza viruses is still required to ensure that stockpiled neuraminidase-inhibitors are effective and that clinicians can be kept informed of the efficacy of neuraminidase inhibitors when treating patients for influenza.

None declared.

This work was funded in part by the New Zealand Ministry of Health and New Zealand Ministry of Science and Innovation.

New Zealand national influenza surveillance is funded by the Ministry of Health who kindly permitted the use of relevant data for publication. We also thank Darren Hunt for his review of the manuscript. Our special thanks to the GPs and nurses, the public health unit coordinators and the participating virology laboratories in Auckland, Christchurch, Waikato and National Influenza Centre at ESR. We also wish to acknowledge the kind support, advice and guidance from Aeron Hurt and Ian Barr at the WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza, Melbourne, Australia. We acknowledge Roche Pharamceuticals for providing sales data on oseltamivir which is presented in this study. We also thank the CDC for sharing the influenza virus RT-PCR protocol through a material transfer agreement. The MDCK-SIAT1 cells were a gift from M Matrosovich, Philipps University, Marburg.