Responding to emerging diseases: reducing the risks through understanding the mechanisms of emergence

Editorial

John Mackenziea

a Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University, Perth, and Brunet Institute, Melbourne, Australia

Correspondence to John Mackenzie (e-mail: J.Mackenzie@curtin.edu.au).

To cite this article:

Mackenzie JS. Responding to emerging diseases: reducing the risks through understanding the mechanisms of emergence. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal, 2011, 2(1):1-5. doi:10.5365/wpsar.2011.2.1.006

Over the past two decades, increasing concern and attention have been directed at the potential problems and threats associated with new and emerging diseases. This has been driven by fears arising from the rapid emergence, spread and public health impact of several recent outbreaks, such as the international spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) (2003), the potential of avian influenza H5N1 to emerge as a highly lethal pandemic as increasing numbers of human cases are reported (2003 and continuing), and the very rapid global spread of pandemic H1N1 influenza in 2009–2010. The emergence of SARS-CoV, in particular, demonstrated the considerable economic, political and psychological effects–in addition to the impact on public health–of an unexpected epidemic of a highly infectious, previously unknown agent in a highly connected and interdependent world. These examples clearly highlight the necessity and importance of global outbreak surveillance for the early detection and response to new potential threats. They also demonstrate clearly that these emergent diseases can move rapidly between countries and continents through infected travellers so that surveillance needs to be transparent and authorities made aware of international disease events elsewhere around the globe. Some of the specific threats to the Asian Pacific region have been reviewed elsewhere.1–4

So what do we mean by the term “emerging diseases,” and how do they arise? The concept, definition and factors contributing to the emergence of disease threats were encapsulated in two reports from the US Institute of Medicine that defined the major issues and described the principal causes and mechanisms leading to infectious disease emergence, as well as discussing possible strategies for recognizing and counteracting the threats.5,6 The most widely accepted definition describes emerging diseases as either new, previously unrecognized diseases that are appearing for the first time, or diseases which are known but which are increasing in incidence and/or geographic range. Examples of the former include Sin Nombre virus, which first came to light in 1993 as the cause of Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in the Four Corners area of the United States of America, and Nipah virus, which was first isolated in 1999 as a cause of acute neurological disease in peninsular Malaysia. Examples of the latter include West Nile virus that unexpectedly jumped from the Old World to emerge in the New World in 1999, and Chikungunya virus, which, with the help of a mutation making it more able to be transmitted by Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, spread from island nations in the south-western Indian Ocean to India in 2005–2006, and then jumped from south-western India to emerge in Italy in 2007. These examples re-enforce the importance of the movement of pathogens through either travel or trade (see below).

Many factors or combinations of factors contribute to disease emergence. They include population movements and the effect of urbanization; changes in land use such as deforestation and irrigated agriculture; increasing globalization of food, trade and commerce; increasing international travel; and changes in human behaviour such as intravenous drug use.7–9 The development of new, more sensitive technologies can also provide improved detection and diagnostic procedures allowing a new dimension to pathogen discovery, thus detecting new or cryptic agents for known diseases.10,11 Other factors that contribute to emergence are microbial mutation and selection and genetic re-assortment that can lead to the development of new genotypes of known diseases, as we see most frequently with influenza A and also in new patterns of antibiotic resistance. Finally, and sadly, known diseases can re-emerge if public health measures are reduced or decline because of complacency or apathy of individuals, communities or policy-makers, as exemplified by reduced vaccine coverage or childhood immunization programmes, or reduced vector control, or because of civil conflict. While all these factors described above are due to human activities, natural causes may also be important in emergence, such as climate change, floods, drought, famine and other natural disasters, and thus should not be forgotten or discounted.

While all these factors have been implicated in disease emergence, the importance of the increase in international travel and the globalization of trade cannot be over-emphasized. This includes the movement of infectious agents between countries and continents and the transportation of vector species to establish in new habitats and ecological niches far from their origins, resulting in countries and areas becoming receptive to exotic diseases. Highly successful examples of this are the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, which has become established in one or more sites on all continents, and the spread of West Nile and Chikungunya viruses between continents. It is probable that West Nile reached the New World through the transport of an infected mosquito on an aircraft to initiate the outbreak. Chikungunya may have been transported by a similar route or through viraemic travellers to India and Italy, but its ability to cause an outbreak in Italy was due to the earlier arrival and establishment of Aedes albopictus mosquitoes, probably transported to their new habitat through the medium of used car tyres on board cargo vessels.

At least four different patterns of disease emergence can be distinguished:

-

new infectious agents as the etiological agents of known diseases, often detected because of the development of more sensitive techniques for detection, exemplified by the first description of human herpesvirus 8, the virus associated with Kaposi’s sarcoma,12 of human coronavirus NL63,13 a new respiratory pathogen, and of Klassevirus 1,14 a new agent causing childhood diarrhoea;

-

known agents of diseases that are increasing in incidence and/or geographic distribution, as seen with the spread of dengue, Japanese encephalitis and West Nile viruses;15

-

new patterns of disease epidemiology or pathogenesis due to mutation or genetic reassortment, as exemplified by the generation of new strains of avian influenza,16 and the severity of new genotypes of enterovirus 71 in the Asia-Pacific region;17 and

-

novel infectious agents as the cause of outbreaks/epidemics of new disease syndromes, as exemplified by SARS-CoV18 and Nipah virus,19 neither of which had been observed previously.

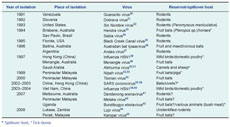

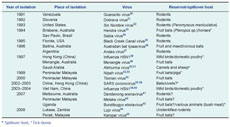

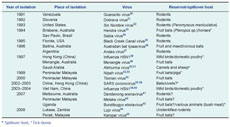

Over the past two decades, approximately 75% of novel viruses have been zoonoses, with new viruses arising from ecological niches in wildlife and domestic animal populations. Indeed most of the diseases with pandemic potential fall into this category. Some examples of these are shown in Table 1, which also demonstrates that emerging diseases may arise anywhere in the world. It is important to understand that although a disease may be new to us, it probably has been circulating in its own specific niche for a long time; we just haven’t encountered it before. There have been many reports of zoonotic viruses described in wildlife, especially bats46,47 and rodents.48,49 In addition, many other viruses and other microbial agents have been described from wildlife in various parts of the world which have not yet been associated with human disease. Thus global surveillance for outbreaks of human diseases alone is insufficient to prepare for all eventualities, and a close watch needs to be maintained on animal diseases, in both domestic animals and wildlife. This need has given rise, in part, to the more holistic approach to surveillance, the concept of One Health,50,51 in which close collaboration is strongly endorsed between human and veterinary medicine through which integrated surveillance should be a major goal.

Table 1. Examples of novel, emergent zoonotic virus diseases

Not all countries have the epidemiological or laboratory resources, or the public health infrastructure, to respond effectively to outbreaks of infectious diseases. For those countries and areas that seek assistance in verification and/or in response and control, the World Health Organization can act, in collaboration with a broad range of partner institutions around the world, together forming the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN), to mount rapid assistance through the provision of expertise and specific resources.

With the advent of the new International Health Regulations (IHR) (2005), there is a strong call for accountability in reporting possible new outbreaks with a potential for international spread. The purpose of the IHR (2005) is “to prevent, to protect against, control, and provide a public health response to the international spread of disease in ways that are commensurate with and restricted to public health risks, and which avoid unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade” (Article 2).52 The accountability is linked to the national or local ability to detect and identify the etiology of possible risks to public health. There is a call to strengthen national capacity for surveillance and response and a requirement to alert the World Health Organization to any public health emergency of international concern. It is hoped that rapid, transparent surveillance procedures will provide an early global alert system to ensure that new outbreaks with a potential for international spread can be identified and controlled.

To ensure that countries have the core capacities to undertake effective preparedness planning, prevention, prompt detection, characterization, containment and control of emerging infectious diseases which could threaten national, regional and global security, the Western Pacific and South-East Asia Regional Offices of the World Health Organization developed The Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases (APSED) as a road map to assist countries in their core capacity-building.53 Considerable progress has been made towards strengthening the core capacities needed to prevent, detect and respond to threats posed by emerging diseases in both regions, and a new five-year plan has been approved to continue the building of core capacity, especially with respect to reducing the risk through strengthening surveillance and thus providing early detection and rapid response to public health emergencies.

Surveillance, early detection and rapid response are certainly the keys to reducing the risks from emerging diseases. To achieve this, there is no doubt that the IHR (2005) will provide the scope and blueprint, but the pathways will require improved surveillance through a One Health collaboration and continued core capacity building in epidemiology, laboratory capability, and other response components through the APSED workplan. However, to achieve a high level of surveillance and an ability to respond rapidly and effectively to infectious disease threats also requires a strong political commitment by policy-makers and governments, and by a cadre of well-trained and committed health workers in several disciplines.

References:

-

Mackenzie JS et al. Emerging viral diseases of South-East Asia and the Western Pacific: a brief review. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2001, 7 Supplement;

497–504.

doi:10.3201/eid0703.010303

pmid:11485641

-

Barboza P et al. Viroses émergentes en Asie du Sud-Est et dans le Pacifique. Medecine et Maladies Infectieuses, 2008, 38:513–523.

doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2008.06.011

pmid:18771865

-

Coker RJ et al. Emerging infectious diseases in Southeast Asia: regional challenges to control. Lancet, 2011, 377(9765):559-609.

doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62004-1

-

Mackenzie JS. Emerging zoonotic encephalitis viruses: lessons from Southeast Asia and Oceania. Journal of Neurovirology, 2005, 11:434–440.

doi:10.1080/13550280591002487

pmid:16287684

-

Lederberg J, Shope RE, Oaks SC, editors. Emerging Infections: Microbial Threats to Health in the United States. Report of the Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC,

The National Academies Press, 1992.

-

Smolinski MS, Hamburg MA, Lederberg J, editors. Microbial Threats to Health: Emergence, Detection, and Response. Report of the Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC, The National Academies Press, 1992. Available from: http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=2008 [accessed

25 February 2011].

-

Morse SS. Factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 1995, 1:7–15.

doi:10.3201/eid0101.950102

pmid:8903148

-

Heymann DL, Rodier GR; WHO Operational Support Team to the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network. Hot spots in a wired world: WHO surveillance of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2001, 1:345–353.

doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00148-7

pmid:11871807

-

Jones KE et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature, 2008, 451:990–993.

doi:10.1038/nature06536

pmid:18288193

-

Lipkin WI. Microbe hunting. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 2010, 74:363–377.

doi:10.1128/MMBR.00007-10

pmid:20805403

-

Svraka S et al. Metagenomic sequencing for virus identification in a public-health setting. The Journal of General Virology, 2010, 91:2846–2856.

doi:10.1099/vir.0.024612-0

pmid:20660148

-

Moore PS, Chang Y. Detection of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in Kaposi’s sarcoma in patients with and without HIV infection. The New England Journal of Medicine, 1995, 332:1181–1185.

doi:10.1056/NEJM199505043321801

pmid:7700310

-

van der Hoek L et al. Identification of a new human coronavirus. Nature Medicine, 2004, 10:368–373.

doi:10.1038/nm1024

pmid:15034574

-

Holtz LR et al. Klassevirus 1, a previously undescribed member of the family Picornaviridae, is globally widespread. Virology Journal, 2009, 6:86.

doi:10.1186/1743-422X-6-86

pmid:19552824

-

Mackenzie JS, Gubler DJ, Petersen LR. Emerging flaviviruses: the spread and resurgence of Japanese encephalitis, West Nile and dengue viruses. Nature Medicine, 2004, 10 Supplement–109.

doi:10.1038/nm1144

pmid:15577938

-

Guan Y et al. Molecular epidemiology of H5N1 avian influenza. Revue Scientifique et Technique (International Office of Epizootics), 2009, 28:39–47. pmid:19618617

-

Solomon T et al. Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of enterovirus 71. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2010, 10:778–790.

doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70194-8

pmid:20961813

-

Poon LL et al. The aetiology, origins, and diagnosis of severe acute respiratory syndrome. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2004, 4:663–671.

doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01172-7

pmid:15522678

-

Chua KB. Nipah virus outbreak in Malaysia. Journal of Clinical Virology, 2003, 26:265–275.

doi:10.1016/S1386-6532(02)00268-8

pmid:12637075

-

Salas R et al. Venezuelan haemorrhagic fever. Lancet, 1991, 338:1033–1036.

doi:10.1016/0140-6736(91)91899-6

pmid:1681354

-

Avsic-Zupanc T et al. Characterization of Dobrava virus: a Hantavirus from Slovenia, Yugoslavia. Journal of Medical Virology, 1992, 38:132–137.

doi:10.1002/jmv.1890380211

pmid:1360999

-

Nichol ST et al. Genetic identification of a hantavirus associated with an outbreak of acute respiratory illness. Science, 1993, 262:914–917.

doi:10.1126/science.8235615

pmid:8235615

-

Murray K et al. A morbillivirus that caused fatal disease in horses and humans. Science, 1995, 268:94–97.

doi:10.1126/science.7701348

pmid:7701348

-

Lisieux T et al. New arenavirus isolated in Brazil. Lancet, 1994, 343:391–392.

doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)91226-2

pmid:7905555

-

Rollin PE et al. Isolation of black creek canal virus, a new hantavirus from Sigmodon hispidus in Florida. Journal of Medical Virology, 1995, 46:35–39.

doi:10.1002/jmv.1890460108

pmid:7623004

-

Gould AR et al. Characterisation of a novel lyssavirus isolated from Pteropid bats in Australia. Virus Research, 1998, 54:165–187.

doi:10.1016/S0168-1702(98)00025-2

pmid:9696125

-

López N et al. Genetic identification of a new hantavirus causing severe pulmonary syndrome in Argentina. Virology, 1996, 220:223–226.

doi:10.1006/viro.1996.0305

pmid:8659118

-

Philbey AW et al. An apparently new virus (family Paramyxoviridae) infectious for pigs, humans, and fruit bats. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 1998, 4:269–271.

doi:10.3201/eid0402.980214

pmid:9621197

-

Claas EC et al. Human influenza A H5N1 virus related to a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. [Erratum in: Lancet 1998, 351: 1292]. Lancet, 1998, 351:472–477.

doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11212-0

pmid:9482438

-

Zaki AM. Isolation of a flavivirus related to the tick-borne encephalitis complex from human cases in Saudi Arabia. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 1997, 91:179–181.

doi:10.1016/S0035-9203(97)90215-7

pmid:9196762

-

Charrel RN et al. Complete coding sequence of the Alkhurma virus, a tick-borne flavivirus causing severe hemorrhagic fever in humans in Saudi Arabia. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2001, 287:455–461.

doi:10.1006/bbrc.2001.5610

pmid:11554750

-

Chua KB et al. Fatal encephalitis due to Nipah virus among pig-farmers in Malaysia. Lancet, 1999, 354:1257–1259.

doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04299-3

pmid:10520635

-

Chua KB et al. Nipah virus: a recently emergent deadly paramyxovirus. Science, 2000, 288:1432–1435.

doi:10.1126/science.288.5470.1432

pmid:10827955

-

Chua KB et al. Tioman virus, a novel paramyxovirus isolated from fruit bats in Malaysia. Virology, 2001, 283:215–229.

doi:10.1006/viro.2000.0882

pmid:11336547

-

Peiris JS et al.; SARS study group. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet, 2003, 361:1319–1325.

doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2

pmid:12711465

-

Ksiazek TG et al.; SARS Working Group. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2003, 348:1953–1966.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa030781

pmid:12690092

-

Drosten C et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2003, 348:1967–1976.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa030747

pmid:12690091

-

Poutanen SM et al.; National Microbiology Laboratory, Canada; Canadian Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Study Team. Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2003, 348:1995–2005.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa030634

pmid:12671061

-

Tran TH et al. World Health Organization International Avian Influenza Investigative Team. Avian influenza A(H5N1) in 10 patients in Vietnam. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2004, 350(12):1179–1188.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040419

pmid:14985470

-

Li KS et al. Genesis of a highly pathogenic and potentially pandemic H5N1 influenza virus in eastern Asia. Nature, 2004, 430:209–213.

doi:10.1038/nature02746

pmid:15241415

-

Palacios G et al. A new arenavirus in a cluster of fatal transplant-associated diseases. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2008, 358:991–998.

doi:10.1056/NEJMoa073785

pmid:18256387

-

Chua KB et al. A previously unknown reovirus of bat origin is associated with an acute respiratory disease in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2007, 104:11424–11429.

doi:10.1073/pnas.0701372104

pmid:17592121

-

Towner JS et al. Newly discovered ebola virus associated with hemorrhagic fever outbreak in Uganda. PLoS Pathogens, 2008, 4:e1000212.

doi:10.1073/pnas.0701372104

pmid:17592121

-

Briese T et al. Genetic detection and characterization of Lujo virus, a new hemorrhagic fever-associated arenavirus from southern Africa. PLoS Pathogens, 2009, 5:e1000455.

doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000455

pmid:19478873

-

Chua KB et al. Identification and characterisation of a new Orthoreovirus from patients with acute respiratory infections. PLoS ONE, 2008, 3(11):3803.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003803

-

Calisher CH et al. Bats: important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 2006, 19:531–545.

doi:10.1128/CMR.00017-06

pmid:16847084

-

Mackenzie JS et al. The role of bats as reservoir hosts of emerging neurological viruses. In: Schoskes C, ed. Neurotropic Virus Infections. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press 2008: 382–406.

-

Gonzalez JP et al. Arenaviruses. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology, 2007, 315:253–288.

doi:10.1007/978-3-540-70962-6_11

pmid:17848068

-

Klein SL, Calisher CH. Emergence and persistence of hantaviruses. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology, 2007, 315:217–252.

doi:10.1007/978-3-540-70962-6_10

pmid:17848067

-

Gibbs EP, Anderson TC. 'One World - One Health' and the global challenge of epidemic diseases of viral aetiology. Veterinaria Italiana, 2009, 45:35–44.

pmid:20391388

-

Merianos A. Surveillance and response to disease emergence. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology, 2007, 315:477–509.

doi:10.1007/978-3-540-70962-6_19

pmid:17848076

-

International Health Regulations 2005. World Health Organization. Available from: http://www.who.int/ihr/en/ [accessed 23 February 2011].

-

Asia Pacific Strategy for Emerging Diseases. World Health Organization South-East Regional Office, New Delhi, and the Western Pacific Regional Office, Manila, 2005. Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/emerging_diseases/documents/docs/

APSEDfinalendorsedandeditedbyEDTmapremovedFORMAT.pdf [accessed

25 February 2011].