Health Impact Assessment of a UK Digital Health Service

1. INTRODUCTION

Recent developments in digital technology have revolutionised the modes and patterns in which we interact, communicate, collaborate and share information. These technologies have a significant impact on information management, process improvement (logistical systems helps organisations deliver better and more efficient results), service improvement, communications, gaming and entertainment, and provision of health care information (Department for Communities and Local Government, 2008).

There is great interest to use digital technology for health provision (to provide information on health promotion and health care services, and support staff training). Digitally provided health services encompass a number of services ranging from health related websites to telecare and telehealth and are regarded as cost-effective interventions. The most commonly used digitally provided health services include web based health information, interactive tools (applications) and support groups, online or computer based learning and training and in-home counselling, assessment and monitoring (Neuhauser & Kreps, 2003). There are new opportunities for health communication provided by Web 2.0 sociable technologies and social software such as health wikis, blogs, podcasts and other applications (Kamel & Wheeler, 2007).

Digital services provide opportunities as well as challenges. There is clear evidence that not all population groups are able to benefit from these technologies because of the digital divide (access to digital technology, literacy and motivation to use technology). The gap between those who have access to digital technology and those who don't is often referred to as the digital divide and implies a dichotomy between the "haves and have nots". Those unable to access the internet are excluded from gaining information, knowledge and skills, and excluded from opportunities to participate in a wide range of activities such as searching for leisure opportunities, travel, educational opportunities, learning and skills training and online shopping (Hughes, Bellis & Tocque, 2002). The digital divide may have an impact on health inequalities by excluding those groups who already experience poor health.

2. WEST MIDLANDS DIGITAL HEALTH SERVICE

A local digitally provided health service (this will be referred to as the Digital Health Service (DHS)) was commissioned by the Regional Office (West Midlands) of the National Health Service (NHS) to run over a five year period and is being delivered by a consortium comprising of media and IT companies and a local university. This DHS is intended to provide "…a range of digital services which through a combination of commissioned and aggregated content, applications and services builds knowledge, disseminates best practice, delivers more cost effective professional development and improves health outcomes for the citizens and staff…" (Turpie, Chitty, Blissett, Flavelle, Branson, Hall & Quinney, 2010).

The service went live in August 2010. This followed a soft launch after an evaluation of the prototype of the service (Ipsos Media CT, 2009) which showed a positive response from the public suggesting they would use the services to look after their own health and well-being, and from staff who would use it in their own professional practice. The DHS aims to: improve health outcomes and health care delivery for patients and the public in the West Midlands; empower patients and the public to make informed choices about their health; and support health professionals and other staff in: delivering safe, high quality, innovative healthcare services, and developing their careers.

The service delivers a variety of health related information (including news, information on health conditions, lifestyle behaviours, health care services and staff training material) through a range of media including short videos, written content, mapping and interactive tools. The service doesn't provide any one-to-one delivery of health care. The editorial agenda is based on local needs and national best practice and the editorial style of the service is open and engaging with videos and stories used to convey information and messages. The content is quality assured by a team including health care professionals and editorial staff. The service avoids duplication of content and provides links to external websites.

In October 2010, a Health Impact Assessment (HIA) was requested to assess the potential impacts of the service on the health of the West Midlands population with a specific focus on the impact on health inequalities. There were two specific questions this HIA was asked to address:

- How will the DHS impact on the health and well-being of people in the West Midlands?

- How will the service impact on health inequalities in the West Midlands?

As the service provides a wide range of information, it was agreed that the HIA would focus on diabetes as a case study to address the health impacts in the region. The West Midlands has a higher rate of diabetes diagnosed than any other English region and this has persistently risen over the last few years. Part of the reason for the high rate of diabetes is the number of adults and children in the West Midlands who are obese which is higher than the national average. In addition the region has fewer physically active adults than in other regions (Association of Public Health Observatories, 2010).

3. HEALTH IMPACT ASSESSMENT

HIA is a "…combination of procedures, methods and tools by which a policy, program or project may be judged as to its potential effects on the health of a population, and the distribution of those effects within the population." (European Centre for Health Policy, 1999).

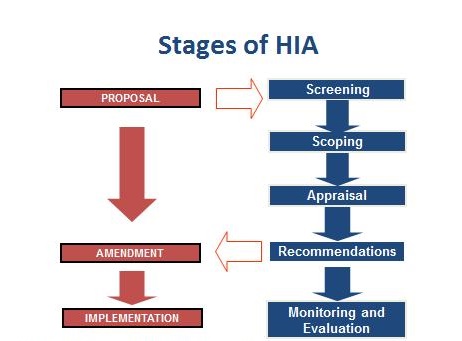

The intended outcome of the HIA is a series of recommendations to minimise or eradicate any potential negative impacts and to maximise any potential positive impacts. HIA considers which key determinants of health will be affected e.g. living and working conditions, social networks, lifestyles, and how these in turn will potentially impact on the health and wellbeing of the population and on health inequalities. HIA has five sequential steps: screening, scoping (planning stage), appraisal of impacts, recommendations, and evaluation (i.e. review of the HIA process, assessment of how the recommendations were used by the decision makers and monitoring the impacts on health) (Figure 1).

This paper reports on two stages of the HIA, appraisal of impacts and recommendations.

4. APPRAISAL OF IMPACTS

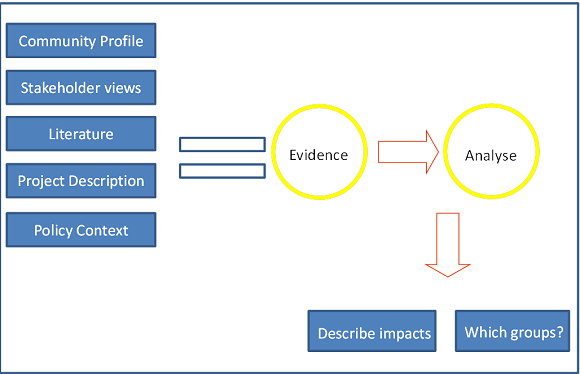

A range of evidence drawn from the literature, stakeholder interviews, and questionnaire feedback from potential users was appraised and synthesised to consider the likely impacts of the DHS on health and health inequalities of the population in the West Midlands. Figure 2 shows how evidence from these different sources is used in HIA to describe the health impacts.

4.1 Policy Context

A number of Government policies have highlighted the importance of using digital technology in delivering health care. The Government aims to provide "…a range of online health services which will mean services being provided much more efficiently at a time and place that is convenient for patients and carers." (Department of Health, 2010). The European Commission (European Commission Information, Society and Media, 2006) also advocates for a new model of health care where information technology has a major role to play.

4.2 Literature review

4.2.1 Methodology

The literature review was based on the search of 10 bibliographic databases (INTUTE, ETHOS, MEDLINE, OVID, WEB OF KNOWLEDGE, WEB OF SCIENCE, COCHRANE, ASSIA, IBSS, and NHS Evidence), searched between September and November 2010. The following search terms were used: "eHealth", "eHealth and health promotion", "eHealth and health education", "eHealth and health inequalities", "internet and health", "internet health and health inequalities", "health and digital services", "social networking", "eHealth and diabetes", and "internet and diabetes". The literature review focussed on access to the internet, access issues in general (including the digital divide), benefits of eHealth, navigation and design issues for eHealth websites, and impacts on health inequalities. The following inclusion criteria were used: publication years 2000 to 2010, English language papers, all countries, and quantitative and qualitative studies. Discussion papers were excluded. Experts also contributed relevant papers and reports. This was not intended to be a systematic review.

4.2.2 Results

Information, knowledge and empowermentEHealth holds the promise to supplement traditional forms of health promotion through user centred design and interactivity, expansion of access to health information, greater discourse and customisation of information to users. A number of perceived benefits of eHealth have been identified in the literature (Hughes, Bellis & Tocque, 2002; Read & Blackburn, 2005; Korp, 2006):

- Availability of a range of health information independent of time and place

- Enhanced knowledge on diseases, lifestyle choices and health care services. This supports decision making thus empowering patients to look after their health

- Opportunity to share experiences and seek advice through social networks

- Provision of training for health care staff

There is sufficient evidence to indicate that provision of health information alone has little impact on people's health behaviour. Providing health information can have an impact on individual's attitudes and beliefs, and when provided with other activities on promoting healthier choices can have an impact on behaviour change (Tones, Tilford & Robinson, 1990). Health information is most effective when: the intended audience is engaged in the programme; the information is targeted at a particular audience; the message source is from the same audience; the message is consistently presented; the message is tailored to individuals and is personalised; and by provision of support to increase motivation of the audience (Boyce, Robertson & Dixon, 2008).

Digitally available health information and resources are shown to increase not just knowledge and understanding of health and conditions but also to reduce anxiety, increase confidence and levels of empowerment. Figure 3 shows how factors derived from the literature impact on empowerment.

In a review of 12 studies (Akesson, Saveman & Nilsson, 2007), eHealth applications increased knowledge, empowerment, confidence and health. Similarly, online health information had a major impact on the understanding of patients' health issues (Millard & Fintak, 2002). In a New Zealand study (Scott, Gilmour & Fielden, 2008) patients were reported to gain many benefits from accessing health information online such as becoming more knowledgeable about their health (37%), gaining helpful advice from patient support sites and consumer groups (24%), accessing second opinions (13%), and support with health needs (13%).

Access to online health information can also impact on the use of health services and seeking support. A significant decrease in the use of GP services as a result of accessing a digital health service was reported in the evaluation of a UK website (NHS Choices) (this was considered to be an appropriate decrease through increased self-care) (NHS Choices, 2010, p22). This contrasts with the findings from another study on young people (Ybarra & Suman, 2008). In this study of 12-17 year olds 55% of all information seekers contacted a health professional because of the information they found on the internet. The online information impacted on other outcomes: respondents felt more comfortable with health care provider information when they tried to diagnose a problem, to treat a problem, and sought support from others. Similarly a qualitative study of older men seeking health information online reported that their fear in managing their disease was reduced, their social support was strengthened, their confidence built and behaviour changes made easier (less than half of the participants had used the internet before) (Lindsay, Smith, Bell & Bellaby, 2007). In another study with older people, retrieval of online information helped them understand health problems, helped change their eating habits, change their exercise patterns and influenced their treatment (Campbell, 2008). Users with long term conditions showed improved knowledge and improved management of their conditions with use of a digital health service (Jones, Goldsmith, Cassola, Duman & Smith, 2009).

In a study of marginalised internet users, increased proficiency in internet use resulted in an increase in understanding of their condition, enabled them to seek support from others, facilitated behaviour change, and increased empowerment to ask questions with health professionals (Mehra, Merkel & Bishop, 2004).

There is evidence that eHealth is used in conjunction with other sources of health information (Kivits, 2006; Sillence, Briggs, Harris & Fishwick, 2007; Kivits, 2009) and the knowledge gained complements medical knowledge and expertise. The internet did not change people's reliance on the medical profession but it opened up new avenues for obtaining information to help make decisions relating to their own health (Nelson, Murray & Kahn, 2010). A study of parents and children with chronic illness (eczema, diabetes and asthma) showed that information was used to clarify and check information received from their doctor, and information was perceived as additional support for managing their conditions (although some parents thought their information needs were adequately met by their health professional), and children felt more knowledgeable after seeking health information online (Nettleton, O'Malley & Watt, 2003).

Digitally provided health services can provide opportunities to establish online support groups which enable people to exchange social support, discuss specific health concerns/conditions, and share information and offer emotional support to each other (Nahm, Resnik, DeGrezia & Brotemarkle, 2009; Wright, Rains & Banas, 2010). A UK pilot study (Armstrong & Powell, 2009) reported that many people living with long-term conditions would like to be in contact with their peers, and internet discussion boards represent a cost-effective and interactive way of achieving this. Participation in online communities have been shown to increase levels of emotional wellbeing, perceived control over disease, overall personal empowerment, and increase medical knowledge (Wicks, 2010). In some studies participation has resulted in improvements in medical decision making and positive behavioural change (Barak, Boniel-Nissim & Suler, 2008).

Healthier lifestylesThere is some evidence on the role of the internet in promoting healthier lifestyles such as increasing physical activity, weight loss and healthy eating. Evidence shows that at least in the short term people improved their diet, reduced tobacco and alcohol consumption and increased safer sexual behaviour (Jones, Goldsmith, Cassola, Duman & Smith, 2009). For individual studies, where access to educational/information websites was compared with the other computer-delivered interventions (CDIs), the CDIs showed a greater improvement than the educational/information websites (Jones, Goldsmith, Cassola, Duman & Smith, 2009). In a meta-analysis of 75 studies on the efficacy of computer-delivered interventions (CDIs) the authors concluded that CDIs can lead to "...immediate post-intervention improvements in health-related knowledge, attitudes, and intentions as well as modifying health behaviours such as dietary intake, tobacco use, substance use, safer sexual behaviour, binge/purging behaviours, and general health maintenance" (Portnoy, Scott-Sheldon, Johnson & Carey, 2008).

Another study on internet-based interventions to promote behaviour change (85 Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) studies between 2000-2008) (Webb, Joseph, Yardley & Michie, 2010) reported that the intervention effect was larger for those studies that included more behavioural change techniques and more modes of delivery. The results showed statistically small but significant effects on health related behaviours. Cushing and Steele's (Cushing & Steele, 2010) meta-analysis of 33 studies on paediatric health promoting and maintaining behaviours using the internet found that eHealth interventions that included behavioural methods (goal setting, self-monitoring, feedback) produced larger effect sizes than those using educational interventions only (small but significant results). A review by Jones et al. (Jones, Goldsmith, Cassola, Duman & Smith, 2009) on weight management reported a great deal of variability among studies which resulted in difficulty in making synthesis and drawing a conclusion.

Management of conditions: specific reference to diabetesPatients have reported improvement in self-management of their conditions by use of online health interventions. A small study (n=16) showed an improvement in the self-management of diabetes (as shown by HBA1c levels) and knowledge of care with a web-based program compared to group lectures for diabetes self-management education (Misoon, Myoung-Ae, Keum Soon, Myung Sun, Insook, Jeongeun, et al., 2009) . Norris et al. (Norris, Engelgau & Venkat Narayan, 2001) found in their meta-analysis of 31 RCTs of self-care education for adults with Type 2 diabetes that glycosylated levels (an indicator of good diabetic control) decreased immediately after the intervention, but that this benefit declined over time. Wanberg (Wangberg, 2007) also showed improvements in self-care by internet based interventions and self-care also increased for other heath areas that the intervention did not target. Patients with poor metabolic control and those with greater use of health care services, higher motivation, and/or less experience with diabetes treatment seemed to benefit more than others from the use of electronic communication. The benefits have also been shown in young people for chronic conditions by improved knowledge and quality of life and decrease in health care utilisation (Stinson, Wilson, Gill, Yamada & Holt, 2009).

Health professionalsThe DHS also provides access to online learning programmes for health care staff. A meta-analysis of studies on internet-based learning for health professionals found that internet-based learning shows large positive effects compared with no intervention and effectiveness is similar to that of traditional learning methods (Cook, Levinson, Garside, Dupras, Erwin & Montori, 2008). A study of Public Health Nurses (PHNs) (Yu, Chen, Yang, Wang & Yen, 2007) in Taiwan (only 9.87% with previous e-learning experience) reported that the majority of PHNs showed a positive attitude towards e-learning. The authors highlighted a number of reasons which encourages adoption of e-learning including availability of a wide range of information, access at own convenience and time and cost- effectiveness. Bond (Bond, 2007) highlighted that computer-assisted education programmes can be an effective tool for nurses to expand their health promotion role.

The study of PHNs reported a number of reasons for not using online learning material including low computer literacy, no access to internet, heavy workload and lack of motivation (Yu, Chen, Yang, Wang & Yen, 2007). In a different study lack of perceived usefulness and lack of perceived pertinence for managing healthcare were also given (Rogers & Mead, 2004),

4.3 Stakeholder interviews

4.3.1 Methodology

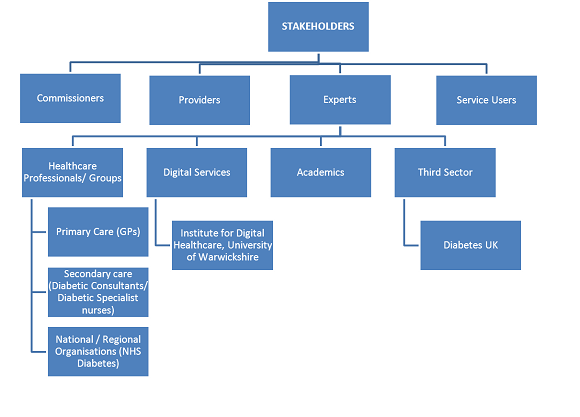

As part of the HIA those involved in the development or delivery of the proposal (the DHS), or who have specific knowledge of the proposal (the DHS) or who are likely to be affected by the proposal are interviewed as stakeholders. The purpose of these in this HIA was to give stakeholders the opportunity to consider what they thought the potential impacts of the DHS and digitally provided health services in general on population health and health inequalities would be, and how any positive impacts could be enhanced, how any potential negative impacts could be reduced and what mitigation measures could implemented. Nineteen people were asked to participate as stakeholders and were interviewed individually between November 2010 and March 2011 (Figure 4). Stakeholders were sent a short paper prior to the interview outlining the purpose of the interview, a brief introduction to the DHS with the URL address, an outline of HIA with the main aims of this HIA, and the questions that would be asked at the interview. Stakeholders were asked these questions but themes emerged in the course of the interviews that were subsequently followed up. Detailed notes of responses were made and were reviewed by both researchers. The main themes and categories were drawn out and any deviant cases noted. This interview and review process was continued for each interview until the HIA practitioners considered that saturation of themes had occurred and no new themes were emerging.

4.3.2 Results

Though there was a lack of clarity around the objectives of the DHS among stakeholders, all stakeholders stated that digitally provided health services have the potential to provide information and resources on health and health care that would impact positively on health and provide health benefits to users. Digitally provided health services could deliver a wide range of information on health; provide information on health services; where to access services locally; provide opportunities for professionals to signpost patients to services and information; contribute to behaviour change; support management of conditions; provide treatment options and choice; provide a "one stop shop" on health information; be a repository for information; provide links to other information; reflect current health concerns; and provide relevant news.

Stakeholders perceived digitally provided health services to be potentially empowering and engaging for people. Tools, appliances and interactivity could encourage people to make changes and increase their engagement. Emergent technology could deliver an interactive intelligent service for users, which could be user-centred and potentially impact on empowerment. Peer support and sharing information were considered important for patient empowerment.

Stakeholders perceived digitally provided health services as having the potential to promote healthy lifestyles and facilitate behaviour change by empowering, engaging, educating and motivating people.

Social support groups were considered to potentially appeal more to the younger age group. Stakeholders also thought online communities and social networking sites were important for staff as well as the public to share ideas, share best practice as well as accessing online training.

The advantages of online training and other online support/information for staff included: saving money, being a "one stop shop" for training, providing information and good practice, providing communities of practice and discussion forums, and enabling access to patient stories and concerns. Online training was an opportunity for blended learning (a combination of traditional face-to-face classroom methods with computer-mediated activities). Disadvantages were: difficulties with evaluating outcomes of training, identifying who completes the training, ensuring all relevant staff complete mandatory courses, lack of staff time, and loss of formality of traditional training delivery.

Other health benefits were identified by stakeholders: reduction in CO2 emissions, (due to fewer car journeys), improved practice by health professionals as a result of accessing patients' experiences and sharing best practice, opportunities to focus on "at risk groups", and potential to improve service quality. (Provision of stories and interactive discussions on digitally provided health services would encourage people to reflect on their own service experiences and by comparison and feedback could potentially drive up service quality).

4.4 User Survey

4.4.1 Methodology

A user survey was conducted with two groups of diabetic patients who were potential users of the DHS. This User Survey focussed on sources of diabetic information, benefits of the internet, use of health related resources (i.e. for diabetes), and barriers to accessing the internet. Members from 2 groups of the Diabetes UK Voluntary Group based in the West Midlands were surveyed in February 2011 using a short paper questionnaire added to the Diabetes UK Feedback Survey. These groups were identified by the regional Diabetes UK office. The questionnaires were provided to all participants at these meetings and collected at the end of the sessions.

4.4.2 Results

Seventy one questionnaires were returned: more than half of the participants were over 64 years of age (37/71), only 7 participants were under the age of 45 years, and almost all (64/71) belonged to the white ethnic group.

Almost a third of the user survey participants had accessed online health information and these many had benefited from this information by improving their understanding of their condition (17/25), knowledge of treatment options (14/25) and management of diabetes (11/25). Users could access a wide range of national and international information that supported existing knowledge. The most common reason for searching online resources was to obtain information on diabetes (23/25).

4.5 Health Inequalities

Health inequalities can be defined as differences in health status or in the distribution of health determinants between different population groups (World Health Organisation). The Government is committed to addressing health inequalities at local and national levels. Marmot's review "'Fair Society, Healthy Lives" (Allen, Boyce, Geddes, Goldblatt, Grady, Marmot & McNeish, 2010) reported that 1.3 and 2.5 million extra years of life could be enjoyed in England if the whole population enjoyed the health of the best group. The review emphasised that in order to reduce variations in health, the scale and intensity of mitigating actions should be proportional to the level of deprivation.

The West Midlands is the 5th largest of ten regions in England and Wales and has a population of 5,431,100 (Office for National Statistics, 2009a) (Office for National Statistics, 2009a). A higher percentage of the population are in the 40-49 year old age band but the 65+ population is projected to increase from 2011 to 2031 (Office for National Statistics, 2011). The West Midlands has a higher Asian population (8.5% of total population) than the National average (6.1%) and a lower White population (85.6% versus 87.5%) (Office for National Statistics, 2009a). The West Midlands ranks second after the North East on the proportion of the total population (16 to retirement age) having a work limiting disability and classed as unemployed (Office for National Statistics, 2009b). Deprivation, children in poverty and statutory homelessness are all worse than the England average (Muir, 2008; Association of Public Health Observatories, 2010).

The health profile for the West Midlands shows that the region has worse health than the England average and there are wide differences in health status across the population and the region (Association of Public Health Observatories, 2010). The 2010 health profile indicated that the life expectancy and infant death rate were significantly worse in the West Midlands region than national averages. All-cause mortality continued to fall over the years but the gap between the regional and national rates remained and the gap between mortality rates from cancer, heart disease and stroke was widening. The poorest health is found in the metropolitan areas and this is largely accounted for by the higher levels of deprivation in these areas; 1 in 4 people in urban areas in England live in low income homes compared to only 1 in 6 in rural areas (The Poverty Site).

4.5.1 Digital Divide

Barriers to accessing the internet and to eHealth are reported in the literature, from stakeholders and from the user survey. These include not having access to a computer and the internet but also (not in order): no perceived need, lack of interest or motivation, lack of skills to find information or sites, low literacy, high equipment and access costs, access available elsewhere, privacy and security concerns, having a physical disability that precludes access, information not personalised, and having questions that cannot be answered (Chang, Bakken, Brown, Houston, Kreps, Kukafka, et al., 2004; Ginossar & Nelson, 2010).

Access and usage to the internet is closely linked to a number of socio-economic and demographic indicators. There are variations in access to the internet by geographical area, age, gender, income, education, occupation and housing tenure. Those groups who either lack access to the internet or are more unlikely to access the internet include women, people over 65 years, households with incomes in the lower quintile, those with no formal education or qualifications, those in semi routine or routine occupations and some ethnic groups (although evidence is equivocal) and carers.

Seventy three percent of households in the West Midlands have access to the internet (a rise of 6% from 2009) compared with 74% of the UK population (internet access by household is higher in London (83%)) (Office for National Statistics, 2010). Using the 2010 UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) data those who had accessed the internet in the previous 3 months of the 2010 survey, 39% had searched for health information (women 44% compared to men 34%) and higher access was reported in the age band 55 - 64 years (44%) and lower access for the16-24 year old group. The ONS survey showed that the common reasons for not having an internet connection at home were: not needed (39%), lack of skills (21%), don't want it (20%), high equipment and access costs (18% and 15%), access available elsewhere (8%), privacy and security concerns (4%), and physical disability (2%) (Office for National Statistics, 2010). During the interviews, it was found that the DHS was not accessible at all hospital sites as the features of the website were not compatible with the IT system at the hospitals.

There was evidence that having internet access did not equate with all members of the household having equal access (Wyatt, 2005). Access to eHealth is dependent on awareness of eHealth websites or eHealth services, motivation to access eHealth, the ability to search and navigate sites, levels of literacy (general literacy, as well as computer and health literacy), being able to use the information and resources in a way which benefits health outcomes, and in most cases being able to read and understand English. Attitudes to computers and the internet affect use and gain from the internet. Simply giving people access to the internet is not enough (Wagner, Bundorf, Singer & Baker, 2005; Dutta-Bergman, 2004). Use is bound up with people's confidence, motivation that they will gain useful information from the internet and that this will be beneficial (self-efficacy), their skills in accessing the information, perceptions of themselves as self-managers of their own illness, experiences of service provision, self-management strategies, and faith in using information to affect health outcomes (Rogers & Mead, 2004).

Researchers have indicated that general literacy, computer literacy and health literacy skills are required when using digitally provided health services (Institute of Medicine, 2009). Individuals with low literacy had difficulty with internet sites and barriers included: spelling, identifying links to other pages, scrolling to find more information, entering internet addresses and using the back arrow (Zarcadoolas, Blanco, Boyer & Pleasant, 2002).

Stakeholders commented on the populations they served and emphasised high deprivation, the need for language translations and ethnic differences as having an impact on access to digitally provided health services. Most stakeholders discussed problems over language and the reliance of patients on interpreters in their clinical practice. An English only site would exclude some groups although translation would also be a problem. Non-medical language was also needed. The digital divide was seen to include older people, the poor, black minority and ethnic groups, homeless and "hard to reach" groups. Older patients were thought to be more comfortable with traditional media. Mitigation measures listed by stakeholders to improve access and usage were: language translations of the site, interventions to reach "hard to reach" groups, greater promotion of the service by staff, expand partners and technological outlets, improve promotion, and increase outlet sites.

Lack of computer skills has been cited by the ONS Survey (Office for National Statistics, 2010) and by the user survey members as a reason for not using the internet. Mehra et al. (Mehra, Merkel & Bishop, 2004) conducted a study on the outcomes of improving computer literacy among marginalised users. At first patients were passive users but as they became proficient and more informed they became instrumental in their use of computers and gained a better understanding of their condition and later sought support from others online. This suggests a timeline in effective usage and in gaining benefits.

There was no available information on access to the internet and use of health related sites specific to the West Midlands but it can be assumed that the above socio-economic and demographic variables and factors affecting access equally apply to the population of the West Midlands. It is expected that internet access will continue to increase but there will always be some groups and individuals who do not have, do not wish or are not able to access digitally provided health services.

4.6 Design of digital services to address barriers and increase access

The following factors were found to be important for use of health information sites: UK based, non-commercial sites, longstanding trusted business sites (such as Boots), professional sites and sites that replicate what is said in other sources of information: lack of advertising, layout and appearance, navigation, readability, quality seal, and third party endorsement were also important (Eysenbach & Kohler, 2002; Zarcadoolas, Blanco, Boyer & Pleasant, 2002; Nettleton, Burrows & O'Malley, 2005; Bodie & Dutta, 2008). Computer tailored information was found to engage users more than information provided in a standard format (Lewis, Williams, Dunsiger, Sciamanna, Whiteley, Napolitano, et al., 2008).

EHealth must also cater for specific groups of users with specific needs and involve them in designing the website. Evidence suggests that specific population groups have specific requirements to enable access to online information and resources such as: translations into community and different languages, culturally sensitive information, varying font size and colour, provision of simple and non-medical language, and easy navigation (Hughes, Bellis & Tocque, 2002). Many people with disabilities can use information technology in the standard way but for some adaptive technologies are needed to access these (Hughes, Bellis & Tocque, 2002). Barriers for accessing eHealth among specific groups were reported to be related to poor site design due to lack of understanding by web designers of the needs of specific user groups, limited use of evidence on usability and effectiveness of sites, and lack of financial incentives to web designers to make these changes (Chang, Bakken, Brown, Houston, Kreps, Kukafka et al., 2004; Ginossar & Nelson, 2010).

In a study that used a user testability methodology with visually impaired users, 40% of users were able to find information before the site was changed but following the design changes based on users' comments 92% stated they were successfully able to retrieve information (Theofanos & Mulligan, 2004). Organisations have produced guidelines for websites with detailed information on accessibility and usability to ensure sites are accessible to all and communicate to all (National Health Service, 2011) (see www.w3.org/WAI).

The evidence suggests that eHealth communication outcomes are likely to be more successful when the recipients of the technology/message are involved in the design and dissemination of the eHealth communication (Kreps & Neuhauser, 2010). Effective health communication must be an active collaboration between sender and user. Effective eHealth design needs to include: interactive communication, work across different communication platforms and with diverse populations, engagement of interests and emotions of users, and reach across diverse populations while adapting to interests and communication orientations of different users (De Vries, Kremers, Smeets, Brug & Eijmael, 2008).

There was a lack of awareness about the DHS among the stakeholders and user survey group. The stakeholders who were already familiar with the DHS thought that the site could be improved as follows: simplified headings (e.g. using "Staff" not "Inside the NHS"), provision of clinically available information on appropriate pages, improved structure for navigating the site, improved links between material, an improved search facility with clearer metadata to accompany this, descriptions given to links, supporting information (e.g. clinical information) alongside stories, and improved content layout. A section on "What do I do next?" would have been useful. The local focus of the DHS i.e. a service for the West Midlands population was thought to be lacking.

5. RECOMMENDATIONS

Specific recommendations were formulated for decision-makers based on the best available evidence reported above. The aim was to provide recommendations that were evidence-informed and achievable. The key recommendations were as follows:

- A clear, timely and funded marketing and promotion strategy to be put in place and targeted at "hard to reach" groups

- Promote and raise awareness among health professionals, third sector and community leaders to promote the service to their users/clients

- Work with partners to provide a variety of access points for the service across a wide range of venues (e.g. GP surgeries, kiosks, places of religious gathering and worship, and schools)

- Link with the national and local initiatives on improving internet access and expand access to the DHS at NHS sites

- Explore translation of key areas of the service into different languages and community languages

- Link with the national and local initiatives on improving computer literacy

- Provide IT training for health professionals (if required) and provide training on how the service can be integrated into care delivery, and how can patients use it

- Engage the recipients of the service in the design of the service including health professionals

- Undertake user testability methodology with users and staff and incorporate findings in the development of the service

- Apply published web design guidelines for specific groups to the development and design of the service

- Ensure that patient and clinical experts are consulted when new content is developed.

6. DISCUSSION

The evidence from the different sources used in this HIA (literature review, stakeholders and user survey) shows that digitally provided health services have the potential to positively impact on health. These potential positive impacts were as follows:

- Increased and improved information and knowledge on health and health care

- Promotion of health and healthy lifestyles

- Support for self-treatment and self-management of conditions and illnesses

- Increased patient engagement with their own health

- Increased use of digital health information in consultation (by both patients and professionals and with each other) and improved interaction

- Provision of a platform for social networking and sharing of information

- Increased support and empowerment for both staff and patients

- Improved quality of care

- Contribution to and facilitation of behaviour change

- Improved access to local services

- Provision of positive learning opportunities for professionals

- Provision of opportunities for staff to learn from patients' experiences of care

- Reduced costs and carbon footprints

- Training of health care staff.

The evidence from all sources found that digitally provided health services will complement more traditional sources of health information and would not wholly substitute face-to-face contact with health professionals. The evidence for the impact of digitally provided health services on health inequalities is inconclusive.

6.1 West Midlands Digital Health Service

The DHS in the West Midlands has been developed within the context of national and regional policies where there has been a continuing emphasis on empowering patients for self-care, on the adoption of healthier lifestyles and on the management of long-term conditions. The specific questions this HIA was asked to address were:

- How will the local DHS impact on the health and wellbeing of people in the West Midlands?

- How will the local DHS impact on health inequalities in the West Midlands?

There was no evidence from the HIA to indicate that the DHS in its current form would have any potential impact either on the health and wellbeing of people in the West Midlands on health inequalities. The reasons for this centred on: differential access (those groups with the poorest health are the very groups which are least likely to access the DHS), difficulties over access to computers, the internet, and the DHS, lack of awareness of the service by both public and staff, the need for improvements in the design, navigation and content of the service, and the need to design and deliver the service to "hard to reach" groups.

A series of recommendations to improve the impacts of the DHS were developed based on the different sources of evidence. The HIA report and recommendations have been submitted to the commissioners and there are current discussions on the recommendations from the report.

During the HIA a review of the service was undertaken by a consulting firm (Vickers, 2011). The review recommended modifying original aims and objectives of the DHS to focus on behavioural change and the provision of a personalised service as opposed to providing general information and content. As a result, the service has moved in to a transition period (between April 2011 and October 2011) with the aims of costing and planning this change in delivery.

6.2 Limitations of this study

The literature reviews included a range of internet based intervention studies that included information/education on the internet and/or email communications, personalised plans and face-to-face interventions. The systematic reviews showed a great deal of variability in results and there are concerns regarding the short term of the follow ups and generalisability of the results. Most studies were from USA and there is a lack of UK based studies. Only a few studies compared the provision of health information provided digitally with more traditional forms such as print format.

There will always be a time lag between publication of the literature and current use of digital technologies. Access to the internet and use of digital technologies are increasing and with this comes a cultural change in acceptance, use and perceived benefits.

Data on access to the internet and health related sites was limited to national sources and there was no specific information relating to the West Midlands region in the UK. Further evidence was drawn from a small and select group of service users. This latter group were diabetic patients, in the older age group (only 7 were under 45 years) and were predominantly white.

Ethical approval

None sought.

Funding

There was no direct funding or grant for this HIA.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.