Perceived benefits of remote data capturing in Community home-based care: the caregivers' perspective

1. Introduction

The community home-based care (CHBC) environment has been encouraged in developing countries as an alternative to formal health care services. This is mainly due to the fact that health care systems in developing countries are weak and not able to provide adequate services to its people. CHBC is used to provide care to patients in their homes without additional costs to the patient. Care is provided by caregivers from within the community, many of them on a volunteer basis. Data are typically collected in paper-based format, with an emphasis on the need to aggregate data, for example 'total number of patients visited'.

M-Health, the use of mobile phones and other mobile communication technologies within the health sector (Mechael & Sloninsky, 2008), is viewed as a channel that can be used to support health workers to provide health services to communities. Its application in the areas of education and awareness, remote data capturing, remote monitoring, communication and training for healthcare workers, disease and epidemic outbreak tracking and diagnostic and treatment support (Vital wave consulting, 2009) offers much promise of its utility especially in resource-poor settings. However, the adoption of ICTs within healthcare organizations, especially those afflicted by elements of social disempowerment affecting the introduction, integration and ultimate recognition of any technological endeavour, is not simple (Van Zyl, 2011).

This paper aims to understand the CHBC environment, the daily work activities of caregivers, factors impacting data collection work and problems community health care workers (CHCWs) face with paper-based systems. Therefore the paper provides a rich descriptive view of the caregivers' daily lives. Based on this understanding, the paper explores the caregivers' notions of the perceived benefits (and disadvantages) of using mobile phones for data collection at the point of care (remote data capturing).

The paper follows from a collaborative research project (De la Harpe, Pottas, Lotriet, & Korpela, 2010) between South African Universities, including Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT) Department of Informatics and Design (coordinator), the University of Pretoria (UP) Department of Informatics, the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) School of ICT, and the University of Eastern Finland (UEF) Healthcare Information Systems Research and Development (HIS R&D) Unit, funded by SAFIPA (South Africa - Finland Knowledge Partnership on ICT). One of the objectives of this project was to apply previously existing socio-technical methods to design and develop innovative ICT solutions to address problems and/or opportunities in practice, using CHBC as an application area.

Within the context of the SAFIPA project, this paper provides a descriptive account of work practices and social relations in a CHBC environment, explores the caregivers' utilization of mobile phones and how they view the possible use of mobile phones for data collection at the point of care. An important reason for the failure of ICT solutions is that their design does not reflect the work practices, social relations amongst the users and socio-economic factors typical of the user community. Further research aimed at addressing this problem is reported in the paper entitled Socio-technical approach to community health: designing and developing a mobile care data application for home-based healthcare in South Africa, in this issue of JoCI (De la Harpe, Lotriet, Pottas, & Korpela, 2011).

2. Methodology

A non-governmental organization (NGO) in South Africa, Port Elizabeth in the township of Motherwell was used as a case study. The Matron, community members and community health care workers who are part of this NGO were participants in this study. The research adopted a qualitative approach. Qualitative research aims to get more insight into human behaviour and the reasons that govern that behaviour. This type of research is concerned with the meanings that people attach to their experiences of the social world and how they make sense of the world (Pope & Mays, 2006). A single case study of an NGO is investigated in this research. A case study is an entity that is studied as a single unit and has clear boundaries, including those of time and location (Holloway, 2008). Six CHCWs were interviewed and two were observed during the execution of their daily work.

3. Case study

3.1 Background

Emmanuel haven was started in 2004 by Dr Mamisa Chabula-Nxiweni with the sole aim of dealing with the growing number of adults and children that are affected with HIV/AIDS (Emmanuel haven, n.d). It is located in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa, 20km's from Port Elizabeth in the Motherwell Township. Motherwell Township is home to approximately 187,680 people and is an area that is afflicted by crime, high illiteracy levels, poverty and a lack of adequate health provision services (DPLG, n.d). Emmanuel haven has various initiatives that it runs such as: farming, brick making, crèche, a community radio station and other initiatives to sustain its work in the community. The home-based care programme has 300 volunteer community health care workers who on average have six patients each (with a maximum of eight patients) to visit per week.

3.2 Daily Activities of community health care workers

A community health care worker visits up to four patients on any one workday. At Emmanuel haven, community health care workers are not rushed to visit all their patients in one day. Instead, they are encouraged to take their time during patient visits to ensure that all the patients' needs are fulfilled. A CHCW's working day lasts from 8am until 2pm with each patient visit lasting between 30 - 60 minutes depending on the patient's condition and the duties that the community health care worker has to perform. The CHCW not only provides care for their patients but also links the family with clinics, hospitals or other organizations that can provide them with support, education and training. This is in line with the integrated model of CHBC as discussed by Uys and Cameron (2003), which extends the concept of CHBC to provide a continuum of care through building a network of support and collaboration.

Apart from performing duties pertaining to caring for the patients' health, community health care workers have to ensure that the environment the patients live in is clean. Scenario 1 demonstrates the various duties other than health care duties that CHCWs sometimes perform as related by one of the interviewees.

Scenario:

CHCW enters patient house and detects an odour

CHCW: Gogo, mani ingathi ilanga lishushu?! (Gogo, it

looks quite hot outside doesn't it?!)

proceeds to open windows

CHCW: Gogo, amathambo, iArthritis ivukile neh? (Gogo, how

is the arthritis?)

Patient: oh mntanam, kange ndilale. (My child, I did not

sleep)

CHCW: Gogo mandiqale nje ngotshayela.. uphi umtshayelo?!

(Gogo, let me start by sweeping the house, where is the

broom?)

Proceeds to sweep the house. If there is any disinfectant

uses that to scrub the floors and bathroom, airs the

beds, wash dishes.

CHCW: Gogo, uke watya? (Gogo, have you had anything to

eat)

Patient: oh mntanam, kange nditye. Nalombani umncinci.

(My child, I have not eaten. This electricity is also

about to run out).

Proceeds to look in the cupboards for food. Finds mealie

meal and cooks that. Dishes up for patient and feeds her.

Also dishes up for herself to show that she is not

disgusted by the patient. After eating, washes dishes,

soaks the dish cloths.

CHCW: Gogo, wethu ndizobeka amanzi nje ukuthi uvase nawe.

Ndizakunceda, ungabi nangxaki wena gogo. (Gogo, let me

heat up some water so that you can take a bath. I will

help so you don't have to worry yourself about it

gogo).

Proceed to wash the patient and dresses the patient.

This account from the caregiver, showing that the tasks of the caregiver extend beyond basic nursing provides insight into the multi-dimensional role they fulfil. This is supported by Friedman (2005) who explains that the role of the caregiver includes acting as advocates to improve health, providing basic counselling services, providing specialised health care services to community members, linking communities to other community service agents such as youth workers or educators and carrying out health promotional activities in order to educate the community.

3.3 Factors impacting the daily activities of caregivers

As much as there are benefits to having an effective HCBC programme, some challenges are unavoidable no matter how well planned a HCBC programme is. The main challenges and limitations facing HCBC programmes according to Browning (2009) and Shaibu (2006) are: poverty, financial constraints, fear of being associated with a HCBC programme, HCBC programmes have no support structures for caregivers, shortage of staff in HCBC programmes and no transport for community health care workers.

In this section, the factors impacting the daily lives of caregivers at the Emmanuel haven are summarized and supported by excerpts from the interviews.

3.3.1 Poverty

Working in poverty stricken areas affects the community health care worker as they feel that they have to be the ones that provide food and clothing to their patients.

"You do become worried when you arrive at a patient's home and they tell you they did not take their medication because they do not have any food."

3.3.2 Lack of basic facilities (water, electricity, proper sanitation)

Most areas in the Motherwell community have been adequately equipped with running water, electricity and proper sanitation. Water is needed to wash the patient and flush toilets, electricity to cook. The CHCWs reported that they are affected by lack of basic facilities if any of these services run out. One interviewee stated that if any of these facilities in a patient's home were to be disconnected, perhaps due to non-payment, they reported this to a social worker who would help the patient get the services reconnected.

"It affects me a lot. Some people are struggling; the only electricity they ever had was the free one you get when you first get a RDP (referring to Reconstruction and Development Programme) house. There is nothing you can do without electricity."

3.3.3 Lack of transport

Motherwell community is one of the largest townships in South Africa and it is divided into units. Even though the patient and the community health care worker might live in the same unit, these are geographically large and the community health care workers have to walk long distances to visit patients. Finances for public transport is scarce and not provided for by the haven.

"I came here knowing that I'm a volunteer and I won't have enough money to use for transport so I had to choose a place to work that was close."

3.3.4 Poor road conditions

Damaged roads are a consequence of the socio-economic conditions in a setting such as Motherwell. Considering the fact that the CHCW's mode of transport is walking, this does undermine the working conditions of the caregiver. The interviewees complained that their shoes get torn and old quickly as the roads are not tarred.

"The poor road conditions do affect me especially when it rains because the roads become muddy."

3.3.5 Weather conditions

When it rains, the road conditions deteriorate even further and they become slippery. Some community health care workers reported that they do not work on rainy days due to the poor road and weather conditions, while others maintained that they have to persevere even in adverse conditions.

"Even if it is raining we have to go visit our patients because at the end of the month we will not have any report to submit."

3.3.6 Crime-ridden areas

Crime had not been experienced by the community health care workers who were interviewed. However, they confirmed the existence of crime threats, indicating that even if they were directly affected, they would still carry on working.

"There are gangsters but I haven't received any problems with them."

"It is not safe because we walk around in our uniform and people think that we have money. It's very difficult especially in NU11. Even your cell phone you have to make sure it's in a safe place."

3.3.7 Remuneration

The community health care workers have to survive on a R600 per month stipend. This is sometimes not enough to feed their families. Additionally, the stipend may sometimes not be paid due to lack of funding from sponsors.

"We still carry on working regardless (referring to pay) because we cannot say to our patients we will not come and look after you just because we have not been paid. That is not the patients fault."

3.3.8 Emotional stress

The CHCWs reported that seeing patients being sick and living in poor conditions affects them emotionally.

"Sometimes I find it hard to sleep at night" (referring to the emotional stress experienced)

3.3.9 Lack of material

The interviewees stated that sometimes there are not enough supplies to replenish their kits and this made it difficult to carry out their daily duties.

"What we struggle with most is our kits. Our kits do not have all the necessary materials that we require."

3.3.10 Discrimination and stigma

Some patients have to deal with the stigma associated with their affliction from both their families and the broader community. One interviewee stated that when some family members find out about a patient's HIV/AIDS status they go as far as putting them out of the house. She stated that this was mostly due to the fact that family members lacked education about this disease.

"What people in the area do is that they gossip a lot and say there is that health worker going into that house it must means there is someone who is not well in that house."

Due to lack of resources, caregivers at Emmanuel haven primarily provide rudimentary nursing and supportive care. Friedman (2002) notes that often 'lip service is paid to the importance of community based programmes without a willingness to provide the type of support lent to hospital and clinic based services'. Friedman further asserts that based on the burden that voluntarism tends to place on the poor; many view the intentional use of this strategy by health services as a form of exploitation. Nevertheless, the practice of CHBC is firmly ingrained in the South African structure of decentralised health services. It is therefore important to listen to the caregivers' voices and formulate strategies to assist them to improve service delivery, one of which is an improved system of record-keeping and information sharing.

3.4 Use of paper-based records

Van Zyl (2011) emphasizes that patient files and information flows are at the core of CHBC and that their proper handling is vital. In this section, the paper-based record-keeping system used at Emmanuel haven is explained with a view to understanding their data capturing requirements and practices.

When a community health care worker visits a patient for the first time, they have to fill in a household registration form. This forms contains details such as: particulars of the head of the household, particulars of the other household members, evaluates the home environment with regard to whether it is a formal or informal house, whether there is running water, electricity and proper sanitation. The second form that they need to fill in is the patient categorization assessment form. This form is used to assess the patient to see how often they would need to receive a home visit. These two forms are only used once when the patient is visited for the first time. On a patient's daily visit the patient record form is used. The patient record form is the one that is used the most as this is the one that the care worker uses to detail the kind of care that was provided to a particular patient. It is required that this form be signed by a family member when the care worker leaves to show that they were actually present at the patient's home.

At the end of the month there are various tally sheets that must be filled in by the community health care worker and the matron of the Emmanuel haven. The community health care worker fills in the NPO home based care patient register form which is used to store the patient's particulars, diagnosis, category, treatment compliance and how they were referred to the community health care worker. The matron has to fill in the comprehensive community based health care tally sheet and the health promotion tally sheet. The comprehensive community based health care tally sheet is used by the matron to tally up the number of patients visited by each community health care worker and what diseases the patients had. The health promotion tally sheet is used to tally the number of health promotions each community health care worker has done.

Four of the six CHCWs interviewed stated that when they visit patients' homes they do not carry the forms; instead they carry a notebook in which they record everything that they do in a patient's home. When they get to their homes, they then fill in the forms based on what they have written in their notebooks. The other two interviewees preferred capturing the patient data during the visit. All the respondents indicated that out of a 30-45 minute visit they could spend between 10-15 minutes capturing data either at the patient's home or at their homes. The captured information must be handed over to the matron at the end of the month to aggregate the data.

4. Problems with paper-based systems

The interviewees reported a number of problems which they have experienced or that can affect them through the use of paper-based systems.

4.1 Weather conditions

When it rains, the forms that the CHCW are carrying get wet or if there is too much wind papers are blown away; either way weather conditions affect the CHCW's data collection work.

"If it's raining papers can get wet and the ink can easily be washed off the paper. Just like today it's raining and I have my file with me and I don't know how I will protect it."

4.2 Patient record forms

The patient record forms that have to be completed after each patient visit, are stored at the caregivers' homes and carried to patients' homes to complete. Alternatively the forms are left at the caregivers' homes and completed at home, based on notes the caregivers make during a patient visit in a diary provided by Emmanuel haven. The forms are handed in to Emmanuel haven to complete the month end tally sheets, where after they are filed in patient files kept at the haven. Various challenges are experienced as related below.

"Papers are easily lost and they are numbered and they can sometimes be mixed up." "Sometimes it rains and the paper might get wet and you lose all the information." "Maybe for example I'm drinking tea and I accidently spill on them." "Let's say you have the forms and I'm coming from work and I haven't put them where I usually keep them and one of my kids writes on the paper or even tears it up."

4.3 Data redundancy

In order to avoid problems associated with forms having to be carried to the patients' homes, some caregivers make notes in a diary during the patient visit and transfer the data to the patient record forms when they return home.

"So when you carry a diary you can keep it dry by hiding it in your jacket, all the information is in the diary and you just simply re-write it in the forms."

4.4 Lack of privacy.

Paper-based forms can be viewed easily by other people as they have no security around them; this can be dangerous as information such as someone's HIV\AIDS status is considered private.

"If the forms are taken home the family might read patients' information and they do not have the right to do this. Even when you are walking in the community you need to keep your things safe and hidden so people can't see as they can start talking."

4.5 Lack of forms

It sometimes happens that the forms that the CHCW requires run out due to a lack of ink or machine breakage. If this happens, the care worker has to use their own money to photocopy the forms that are required and this can be costly for the CHCW.

4.6 Too much paperwork

The CHCWs reported that having to record all patient information by hand and having to do the tallying up at the end of day and month was time consuming. They also have to ensure that their English grammar and language use are correct as it would cause problems if the coordinator could not understand what they meant to say.

"You write until your arm becomes sore. There's a lot of paper-work."

4.7 Inaccurate information

The accuracy of the aggregate data depends on the accuracy of the records that are kept by the caregivers. These are sometimes incomplete, handed in late or not completed at all.

"I usually ask the volunteers to write the patient's disease because we have to count these and they sometimes don't do that and it becomes troublesome for us. Some of them bring the reports in late after we have submitted. Some also say they did not have papers to photocopy."

To summarize, the paper-based record-keeping system used by Emmanuel haven is prone to errors, time-consuming and hampers rather than supports the CHBC service. This system cannot support the integrated CHCB model followed by Emmanuel haven appropriately because this would require sharing of information between the partners in the care continuum, which is not possible using a paper-based system. This leads to an assumption that data flow can be improved through the introduction of appropriate ICT solutions. For the purpose of this paper, the possibility of using mobile phones for remote data capturing was discussed with caregivers to determine their perceived notions about this.

5. Caregivers' views of using mobile phones for remote data capturing

3.8 out of 5.3 billion mobile phone users in the world belong to developing countries (ITU, 2011). This indicates that mobile phone usage in developing countries is popular and this could be advantageous for its use as an ICT enabler.

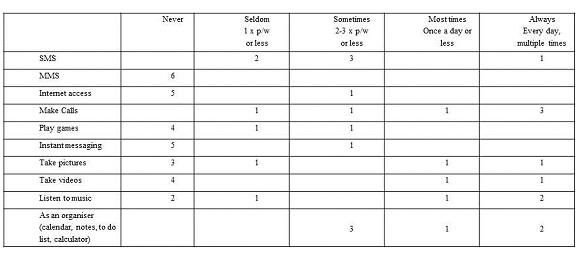

All of the community health care workers interviewed owned a mobile phone. Three out of six of these mobile phones were basic, low-cost phones with limited capabilities. Nevertheless, they were familiar with the use of a mobile phone. In order to gauge their utilization of mobile phones, interviewees were asked to rate their mobile phone usage as an expression of average use of functions in any one week. The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Mobile phone usage rating

It was interesting to note that despite numerous references to limited airtime during the interviews, three of the interviewees indicated that they make calls on their phones multiple times per day, while only one had an equal usage rating for the more economical service of SMS. The only services that were used by all caregivers were making calls, sending SMSes and the organiser function (with specific reference to the calculator).

Despite the fact that none of the caregivers had used a mobile phone for remote data capturing, it was felt that probing their perceived notions of using mobile phones for this purpose, would assist in establishing a baseline in terms of their expectations. This will be important to manage when introducing mobile phones as a technological solution for data capturing in this environment.

All the interviewees responded positive to the suggestion of replacing the paper-based system with a system to capture data through the use of mobile phones. One interviewee exclaimed "please!!!" when presented with this option. The benefits perceived by the caregivers far outweigh the disadvantages. In fact, there was clear overstatement in some cases, for example:

"I don't see anything that would make using the phone difficult. Would there be? It would be a phone for work not for private use? Therefore I wouldn't say I don't have airtime. I won't say I didn't visit a certain patient because I didn't know how to do something on it. The phone would be made in such a way that it would always be working all the time."

Loss and exposure of data were well-recognized as disadvantages. One interviewee explained a situation where her bag with the information could be stolen and the papers that she uses are stolen but then she realized that the same could happen with a phone. Others stated:

"Maybe if it had to be lost or for example if someone didn't know it was for work ... they could steal it from me. That is where the suffering would begin because all the information would be lost." "I have a child that loves technology and phones. What if they go through my phone and find information that so and so has this disease." "Even in the house your phone must not be a plaything because it contains very private and important patient information. It's between you and the centre only. So nobody not even your husband must touch your phone."

It is important to highlight that while caregivers felt comfortable to use mobile phones for remote data capturing, they acknowledged the fact that training would be required.

"I can't use my phone properly, I only use it to say "hello". "Hopefully I would be taught how to use the phone because I do not know these modern phones."

The perceived benefits of using mobile phones for data capturing as stated by the caregivers, are:

- All the interviewees believed that using the mobile phone would be quicker and easier than using paper-based systems.

- The interviewees believed that if information is stored on a mobile phone it is safer and it is kept more private because there is some security involved in a mobile phone.

- When using mobile phones they pointed out that they won't have to carry a lot of forms and wouldn't have to waste their money to photocopy the forms if they had ran out at the haven or if the machine broke.

- They argued that if a phone gets wet, it might get damaged but the information in the phone will not get damaged therefore they perceived that the phone was able to overcome the weather conditions that affected the paper-based forms.

- They preferred mobile phones because they wouldn't have to use paper-based forms and they would be able to take the phone home with them which would have the patient's entire record.

- One interviewee stated that by using a mobile phone, it would be able to organize the patient files and there wouldn't be any mix-ups like in paper-based systems.

- They perceived that information that is on a mobile phone is always available when needed and that they wouldn't have to search through a lot of files to get to the information needed.

- Their feeling was that using a mobile phone would ensure that information is more legible unlike when writing with ink on paper.

- An interviewee stated that most mobile phones have SMS capabilities which could be utilised to send information via SMS. She felt that it could be backed up in that way and that maybe at the end of each day the information collected could be sent to their superiors and this would also serve as a form of backing up information.

- Community health care workers believed that by using a mobile phone to store captured data they would be able to access old patient records and see what diseases a patient has suffered previously to ensure that what a patient says to them does not contradict with what is actually in the patient's record.

The benefits as perceived by the caregivers may not be realizable in all cases. For example, it will indeed be easier to travel with and protect a mobile phone from inclement weather; however, a mobile phone is still susceptible to damage which can lead to data loss. Mobile phones are further limited in the amount of data that can be stored locally, especially the more basic models. Using more expensive phones with advanced capabilities (in order to support local access to patient records) will have cost implications. Implementing a model to remotely access patient records will similarly have cost implications, both of which can affect the viability of using mobile phones in this environment.

Access to information seems to be a key perceived benefit as evidenced in the following statements:

"I think using a phone would be easier. When you visit a patient's home you just carry a phone and it already has all the information." "Searching for information. You can also go back to a certain date to find information." "Through the use of phones I will at least be able to have access to the patient information even during weekends and I can view this while at home. I won't have to wait to go to work before viewing my patient's information." "By using a phone you can be able to search for information on the phone."

One interviewee explained how she mostly sees it for the benefit of being able to keep information, so that she can verify what was said before, in case patients and family change the story later.

Therefore, it emerges that access to patient data on a 24/7 basis is seen as a core benefit. This is an interesting finding, as the caregivers did not highlight lack of access to patient records as a limitation of using a paper-based system. At the very least this expectation (or perceived benefit) implies that simply using the mobile phones to capture data and sending it to a remote data store with the intention of aggregating the data to complete reports (as is the case with the paper-based system), will not meet this expectation of the caregivers. This suggests the need for a more comprehensive solution which enables continuous access to patient records.

6. Conclusion

Community caregivers are collectively responsible for the bulk of the hands-on care provided to people with HIV/AIDS by home care programmes in South Africa (HPCA, 2009). This paper provided a rich descriptive view of the daily lives of caregivers volunteering at the Emmanuel haven NGO in Motherwell, South Africa, the problems they experience with paper-based record-keeping systems in the execution of their daily work and how they feel about using mobile phones for data capturing.

It is concluded that (1) the paper-based record-keeping system does not support the integrated CHBC model appropriately in terms of data flow; (2) the caregivers experience the paper-based system as a burden; (3) the paper-based system does not support a core need of the caregivers to have 24/7 access to patient records; (4) a mobile solution could improve data capturing and information sharing in CHBC; and (5) the caregivers are willing to use mobile phones as an alternative data capturing tool and they perceive this mechanism to hold many benefits (not all of which may be realizable).

It is recommended that the expectations of the caregivers be managed appropriately in further endeavours to introduce mobile phones as a data capturing mechanism in this environment.

The understanding gained of the social relations and work practices in CHBC, including the use of the paper-based record-keeping, provides discerning insights into the challenges caregivers face in their daily lives. As custodians of the wellbeing of their communities, their perseverance and dedication despite a lack of resources and proper support are astounding. The caregivers are ideally placed in their communities to serve as catalysts for improved wellbeing. However, their work must be supported and integrated to realize the potential of an expanded and improved healthcare service. It is hoped that this research will assist to inform the design of appropriate mobile solutions to both ease the burden of caregivers (i.e. it should be faster and easier to use than paper) and improve the healthcare service provided through enabling access to patient records to all partners in the care continuum.

7. Acknowledgements

The financial assistance of the South African Government (Department of Science and Technology) and the Government of Finland (Ministry for Foreign Affairs) through SAFIPA (the South Africa - Finland Knowledge Partnership on ICT) is hereby acknowledged. The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the SAFIPA Socio-Tech SA project partners, viz. Dr Retha de la Harpe (CPUT), Prof Hugo Lotriet (UP) and Prof Mikko Korpela (UEF).