'MYBus': Young People's Mobile Health, Wellbeing and Digital Inclusion

Introduction

This case study draws on debates around digital inclusion and how digital technologies support access to health services for those who are socially or economically disadvantaged. Digital inclusion (or e-inclusion, Fuchs, 2010) recognises that access to, and effective use of, digital technologies today is necessary for communication, information access, economic and cultural participation, and social connection; yet research shows such access, in the global North, is differentially distributed according to gender, class, race, education, geography and age (see for example Livingstone and Helsper, 2007; Maher, 2008; Selwyn, 2004; Warschauer, 2003). Researchers and policy makers now argue that digital access is important for the development of social connectedness and capital to provide a means to connect and interact, and thus establish and maintain social, economic and civic relationships (see Wyn et al., 2005; Quan-Haase & Wellman, 2004; Pew Foundation, 2006).

Digital inclusion is, thus, situated as a new item on the inclusion agenda, operating alongside other recognised factors important for supporting social inclusion - access to economic, health, education, housing, recreation, culture and civic resources. Yet, digital access is not simply an additional determinant of inclusion or wellbeing, but critically implicated in all others, as information and communication technologies increasingly operate as mediators to accessing and utilising services, especially as online resources have become more integrated into social life. Consequently, limited access or skills with digital technologies can contribute to existing forms of social inequity, such as socioeconomically disadvantaged or geographically isolated groups unable to afford, or to easily and regularly access equipment and services (McLaren & Zappela 2002; Curtin 2001; Holloway & Valentine, 2003). This exacerbates inequities in areas such as health provision and literacy, which increasingly rely upon online resources for their operation.

This broader role in mediating inclusion, connectedness and wellbeing is increasingly acknowledged in relation to other social determinants of health (e.g., Golder et al., 2010; Meredyth et al., 2006), as well as in influencing health and wellbeing outcomes for young people (e.g., Wyn et al., 2005; Blanchard et al., 2007). Within these literatures, it is also acknowledged that digital inclusion requires more than just Internet access, but that access is complicated by the social politics of use. Research in Australia and elsewhere shows, for example, that in developed countries the vast majority of people, and especially young people, have some kind of access to the Internet including connected computers at home, school or in a public space, as well as mobile devices (ABS, 2009; ACMA, 2007, 2009a; Livingstone, 2009). Yet there is no simple equation where access equals inclusion. Instead, there is widespread agreement in the research literature that technology access must be accompanied by a range of social and educational resources in support of its use (e.g., Seiter, 2005; Valentine et al., 2002; Warschauer, 2003). Warschauer (2003) notes, for example, that access and inclusion require a range of interconnected resources: physical (hardware device); digital (connection); human (literacy); and social (social networks). This recognition has shifted the terms of the debate about a digital divide and the presence or absence of an Internet connection, to one of digital participation which focuses on a gradient relating to the contexts and quality of access, as well as the integration of technologies into communities and institutions.

In this paper we report on a case study of MYBus, a community mobile youth centre operating in Cardinia Shire, an outer urban growth area of Melbourne. The case study is drawn from a larger ethnographic study of young people's use of information and communication technology in mediating social inclusion. The MYBus is a converted passenger coach which is designed to provide youth aged 12-25 with mobile access to health and wellbeing information and services. The aim of MYBus is to provide young people with a range of up-to-date youth-specific information and resources, and it has been fitted with laptop computers, Internet access, Wii games, D.J. console and other gaming devices to support this engagement. We argue that the context, aggregation and use of digital media on MYBus are an example of digital inclusion that benefits the community and young people in particular.

Our paper identifies the potential for the MYBus project to contribute to young people's health literacy. Writing in her report to the South Australian government, Ilona Kikbusch tied the health literacy debate to control over life circumstances, disadvantage and equity. Her definition of health literacy recognises that it "enables people to increase their control over their health, their ability to seek out health information, to navigate complex systems, take responsibility and participate effectively in all aspects of life" (Kickbusch 2008, p.46). She went on to argue for special support to the most disadvantaged to manage their health and navigate the health system and that children have a right to learn about health and gain health literacy skills in order to counteract major health inequalities.

Yet, not only does MYBus have direct healthcare benefits, such as providing health information, it also enables a broader approach to young people's wellbeing, providing resources for digital access and participation. In particular, we argue that the making mobile of these resources and technologies operates to challenge a range of economic and social disadvantages facing young people living on the urban fringe. We first discuss the importance of the MYBus mobile youth service in relation to the Shire location, demographics and characteristics, in order to highlight how it operates to challenge geographic and socioeconomic inequities for young people living in Cardinia. We then move into an analysis of the importance it plays for young people's digital inclusion through research findings relating to digital access, digital mediation, and digital mobility. Finally, this empirical work is situated theoretically by connecting mobile digital inclusion with literature on young people's social capital, to develop a concept of children's e-mobility capital.

Research Methods

The case study is drawn from the Screen Stories research project, which looked at the role of technology for supporting young people's social inclusion, and worked with five families (10 parents; 9 children) over a period of three months with multiple visits per household during 2010 (see: Gibbs et al., 2010; Nansen et al., 2012). The research took place in the Cardinia Shire, an outer-urban growth area of Melbourne, and used multiple participatory methods to explore local and typical uses of media and communications technologies. Methods included a number of tours and exercises within the home, such as mapping and discussing hardware placement, online activities, and time-space relationships of technology use. It also explored the role of technology use beyond the home by using mobile methods (Ross et al., 2009) in which participants guided us around the different places where they used information and communication technologies in the community, such as the school, workplace and library. It was during this research that we heard about the significance of MYBus for young people's technology access. Whilst the children in our study were too young to use the MYBus, we followed up on this finding by talking with community and youth workers at the Council about the history and use of the MYBus, and by arranging to spend some time on the bus whilst it was visiting youth in the community to observe young people's use of the onboard technologies.

In combination with the fieldwork research, this case study also draws on literature from and about local Cardinia Shire (e.g. Council Youth Forum Surveys; Community Indicators Victoria; ABS), building on the evidence from previous research and relevant data.

Study Location

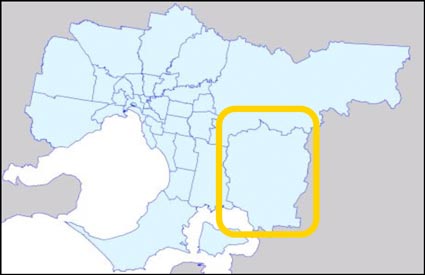

Cardinia Shire, where the MYBus service operates, is located on the south-east fringe of metropolitan Melbourne (see Figure 1). Pakenham, its main urban centre, is 55 kilometres from Melbourne CBD. Cardinia is one of five designated growth areas under the State Government's Melbourne 2030 plan and has a large rural population in addition to the townships designated for rapid urban growth along the highway. The Shire is divided into three distinct geographic subregions - the northern hills area, the southern rural area and the urban growth area - which results in varied service provision needs across the Shire (Cardinia Shire Council, 2009). Cardinia Shire had a population of 64,310 in 2009 including an estimated 14,886 young people aged 10 to 25 years old (Informed Decisions, 2009). The Shire's population is forecast to grow to 143,312 by 2031, and is forecast to include 30,172 young people aged 10 to 25 (Informed Decisions, 2009). This area faces changes resulting from rapid development, particularly in relation to demands on transportation and services (Birrell et al., 2004).

This rapid growth, Robson and Wiseman (2009) argue, has the potential to create social exclusion. Urban-fringe areas, or so-called 'interface municipalities' (NLT, 2006), such as Cardinia, face particular challenges in delivering community and health services due to geographic and demographic characteristics including a mix of rural and suburban, dispersed populations, and high rates of growth (Marsten et al., 2003; NLT, 2006). Service delivery does not cope well with these challenges, as reflected in the Cardinia council's Municipal Public Health and Wellbeing Plan 2009-13 (MPHWP). The plan acknowledges social determinants of health and wellbeing, and recognises that a range of activities and services can affect health within the community, including employment conditions, housing options, lifestyle practices, transport availability, access to open spaces, community services and facilities (Cardinia Shire Council, 2009; WHO Europe, 2003).

A principal social determinant of health affecting local residents that is often identified is the geography and associated isolation and transportation issues. A recent analysis of the area, for example, noted that, "within Cardinia Shire there exist geographically isolated townships whose households have limited economic resources and limited access to basic services" (Wilks, 2010, p.iii). This disadvantage is reflected in The Socio Economic Indices for Areas (SEIFA), which shows that whilst the overall municipality of Cardinia Shire has below average levels of disadvantage (ABS, 2008), there remain areas of disadvantage across the municipality with a number of townships scoring below 1000 on the SEIFA scale indicating they are areas of relative high disadvantage (Wilks, 2010). Thus the service response challenge is "to balance the needs of disadvantaged townships in the southern rural region (e.g. Lang Lang, Koo Wee Rup) with the demands of townships along the highway line and in the northern hills region" (Wilks, 2010, p.iii), (e.g. Cockatoo, Emerald) - see Figure 2.

The geographic size and topography, dispersed population and changing demographics of the area pose particular problems for transport infrastructure and provision (NLT, 2006; Cardinia Shire Council Community Services Unit, 2010); currently "the Shire spans 1,280sq km (one-eighth the size of metropolitan Melbourne)… [but] only has one train line and 10 bus routes passing through or in the municipality" (Cardinia Shire Council, 2009). Cardinia Shire Council community surveys, forums and feedback show that residents view the lack of public transport and public transport connectivity as a significant barrier to accessing services (Cardinia Shire Council, 2009). This is particularly true for young people, with the Youth Forum Surveys consistently showing that young people identify the cost of transport and the lack of public transport options to access work, education and social activities as a major issue (Cardinia Shire Council Community Services Unit, 2010). The lack of public transport and public transport connectivity can also have a 'knock-on' effect, with one problem contributing to or compounding another (NLT, 2006). The 2009 Cardinia Shire Council Youth Forum Survey reports, for example, that young people felt there was a lack of accessible and affordable activities available to them, and that the difficulty of accessing services is directly linked to the lack of reliable and regular transport.

The Municipal Public Health and Wellbeing Plan 2009-13 (MPHWP), the Cardinia Shire Council Youth Forum Surveys, and reports such as the 2007 report 'Staying Connected: Solutions for Addressing the Service Gaps for Young People Living at the Interface' commissioned by a group of local government authorities, recognise many social, environmental and geographical circumstances that can generate and maintain inequalities in health. They make recommendations for strategies to respond to these inequalities. Nevertheless, the focus on social health determinants in these reports has meant they have not yet not adequately acknowledged or addressed the direct role played by information and communication technologies in relation to broader socio-economic health determinants (Golder et al., 2010).

MYBus and Digital Inclusion

The strategic objectives of the Cardinia Municipal Public Health and Wellbeing Plan 2009-13 (MPHWP) include efforts to improve access for young people to health and community services, and to public transport and access to activities and opportunities for education, work and community involvement. Council's MYBus mobile youth bus was launched in June 2009 as part of this wellbeing strategy, and in response to issues identified in youth forum surveys. Whilst MYBus does nott address lack of transportation for young people (to work, school or services), it does provide information about locally based activities (Cardinia Shire Council Community Services Unit, 2010). The MYBus service is an example of a so-called 'generalist' youth support service, which provides local, free and universal access, and which directs its energies at prevention and early intervention strategies. Similarly, the youth workers state that they focus on prevention and early intervention by providing a range of health promotion information and support to young people, building relationships and trust with the youth population, and offering referral to other services where appropriate.

MYBus, shown in Figure 3, is operated by the Cardinia Council Youth Services Team, and it is driven to different locations and events in the Shire throughout the year. The bus regularly visits different secondary schools in the Shire, including schools in disadvantaged townships in the southern rural and northern hills areas. It is used by students during lunch time and after school during semester, with permission from those schools. It also attends youth focused events and festivals within the Shire on weekends and holidays, and provides a range of free school holiday activities for young people. The MYBus service is designed to provide youth with mobile access to healthcare information and services, as well as information regarding local services, programs and events available to young people in the Shire; it "provides relevant and up to date information about drugs and alcohol, sexual health, health and wellbeing and other youth-related topics" (Cardinia Shire Council, 2011). Onboard, the council's youth outreach officers are available to discuss any issues or concerns young people may be experiencing. These officers can also link young people to other services and programs if needed.

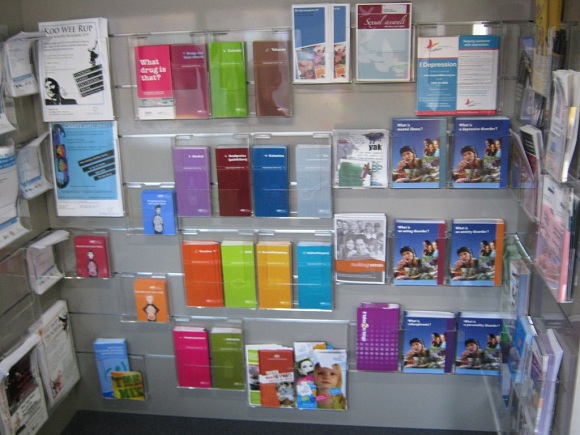

Figure 4 shows how, in order to engage and support young people, the bus is fitted with digital technologies for communication and entertainment and a kitchenette to prepare food and drinks for events. The appeal of laptops and game consoles means that young people of many ages visit and use the MYBus when it is in their area, not only for seeking information but also to play and socialise. We observed that the placement of services on the bus, with the game consoles at the back, laptops in the middle, and brochures at the front, spatially distributed different age groups according to interests and needs, and enabled officers privacy to deliver health and wellbeing information.

The MYBus service recently celebrated two years of service (Cardinia Shire Council, 2011), and receives funding support from government departments and private businesses. While it is a relatively new service it has provided outreach to young people in the Shire: between June 2009 and June 2010 the MYBus had "travelled 41,510 km, visited 18 different townships across the Shire, run school holiday activities at 15 different townships, and attended 13 local events and festivals. Council's youth outreach officers have delivered 13 workshops or personal development programs at local secondary schools. MYBus had about 9,500 contacts with young people from June 2009 to June 2010" (Cardinia Shire Council Community Services Unit, 2010).

Figure 5 shows how MYBus provides health care information, services, support, and referral - in particular relevant information about drugs and alcohol, sexual health, and other youth-related health and wellbeing topics - for young people. In addition to the print material onboard and the presence of youth outreach officers, we argue in this paper that the digital technologies and resources on board also allow young people to access online information, participate in social media communication, and interact with games devices in ways that not only provide health benefits, but also support a broader agenda of digital inclusion. In particular, we suggest it is the mobility - the mobile operation - of these services and technologies, which has underpinned the success and benefits of MYBus.

Researchers are arguing that digital inclusion and participation is part of a broader socio-economic and socio-technical determinant of health and this is reflected by Community Indicators Victoria (CIV), for example, including home Internet access as a wellbeing indicator for local communities (http://www.communityindicators.net.au/). Derived from the 2006 Census question, whether the Internet can be accessed at this dwelling, and if so, what type of connection (broadband; dial-up; other) is available, this indicator recognises that the Internet is increasingly required for accessing essential information and services, for conducting social exchanges, and for participating in the digital economy (ACMA, 2009b). Moreover, this indicator recognises that the quality - type and speed - of connection is also important for social and economic participation. Thus households without Internet access, or with only dial-up service, are increasingly digitally excluded and potentially at a social disadvantage as a result.

In addition to home access, public Internet access has its place in facilitating digital inclusion, yet in a study of digital technology access amongst disadvantaged groups in South Australia, Newman et al (2010) found mixed experiences of public access. They argue that public access cannot be seen as the solution to flattening the digital gradient because it does not support the same quality, frequency, extent or timeliness of use as compared with private home access. One barrier they found was that those with transport or mobility difficulties can not easily travel to public locations. They recommended a Canadian idea of extending ICT Community Access Programs with a mobile-service which takes digital technologies to people's homes in the same way as a traditional mobile book library, as a way to help overcome mobility problems for some population groups. This study resonates with ours because it is Australian, supports geographical and transport barriers to digital access and use, and highlights the need for research into mobile solutions. Further, Newman et al (2010) called for "the identification of practical pathways to increase people's levels of resources and capabilities to use digitally-mediated communication." Our study of MYBus builds on these conclusions and suggested agenda for research and practice.

Findings and Discussion

Digital access

Young people access the laptops mostly to access Facebook, YouTube, play games and to research information for school assignments as they may not have Internet access at home (Anonymous Shire employee)

The most recent data from Community Indicators Victoria about Internet access reveals that overall Cardinia Shire has a larger proportion of households with either no Internet connection or a dial up connection (55.3%), and a smaller proportion of households with broadband connectivity (38.6%), compared to the Melbourne (statistical division) average (49.2% and 42.8% respectively). Moreover, this access varies within the Shire, with households in the southern rural area (see Figure 2) having an even larger proportion of households either without an Internet connection or with only a dial up connection (65.4%), and an even smaller proportion of broadband connectivity (28.1%).

Digital access, inclusion and advantage vary across the Shire; including differences in service options, varied commercial provision of ICT infrastructure and especially the lack of broadband access in more rural areas. In addition, there are a range of social barriers to the uptake and use of broadband, including income and educational qualifications (ABS, 2006; Ewing & Thomas, 2010; Newman et al., 2010), as well as perceived cost, literacy, and a lack of understanding about broadband benefits (DCITA, 2007; Wilken at al., 2011).

Adults in Cardinia may possess the agency to manoeuvre around poor communication infrastructures, and to mitigate poor home connections by accessing multiple sites of communication, including work-based Internet for some of their needs (e.g. Gibbs et al., 2010). Young people, in contrast, are less mobile, and less able to travel to access the Internet (Cardinia Shire, 2010). Further, young people's Internet access in Cardinia and more generally is dominated by home provision and use (ACMA, 2007 ;Gibbs et al., 2010; Nansen et al, 2012). Young people in the Cardinia Shire have limited access to the Internet in the community. Computers and the Internet are occasionally used at school, but only in a limited and supervised manner directed at specific learning activities (Gibbs et al., 2010), and at the public library, but again this is limited to certain times of opening and durations of permitted use. Thus home use emerges as the most significant place for young people's digital access and use.

The youth forum survey shows that for young people in Cardinia, 'surfing the Internet' is their second favourite activity undertaken in leisure time (Cardinia Shire Council Community Services Unit, 2010). Yet, as the evidence noted above shows, online access and use is not evenly available or used. The Cardinia MYBus service is, however, one place where young people are able to use computers and gain digital skills, literacy, and inclusion outside of the home or school. In response to inadequate broadband connections in some homes, the bus provides avenues for young people to negotiate paths to Internet use; especially as it provides this access at convenient times and locations for young people outside schools and outside school hours.

We argue that MYBus implicitly addresses digital inequity and exclusion. Whilst the technologies on board are predominantly there to attract young people as part of youth engagement and outreach, the quote from the Shire employee (above) shows that it also enables access to online information and services, social connectivity, and play. In some ways, then, it challenges social divisions for young people, particularly socio-economic and geographic divisions, providing for digital inclusion.

Digital mediation

Young people use the laptops on the bus for a variety of reasons. The common use is for homework (use Google to search for things), to socialise (Facebook), to play games and to look at videos such as Youtube - dance videos are really popular (Anonymous Shire employee)

Younger children aged 10-12 are not up to the level as young people who are at high school. Often we need to show the younger aged how to use Google for free games. Young people aged 10-12 generally don't have a Facebook account due to parents not wanting them to have it (Anonymous Shire employee)

The barriers to young people's computer and Internet use, engagement with digital technology, and the role played by digital technologies in accessing health information and services, in the Cardinia area are not only influenced by cost and location of access, but also by the governance of technology use. Evidence shows that young people's access to communication technologies at home and at school is subject to restrictions, or what is described in Internet studies as mediation. The mediation literature has studied the range of measures used to manage or regulate young people's use of and safety on the Internet (e.g., ACMA, 2007; Livingstone and Helsper, 2008; NetRatings Australia, 2005, Nikken and Jansz, 2006; Roberts et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2005). Parents, for example, implement a number of rules or measures to direct, limit and supervise young people's use, and thus protect them from perceived or potential risks; regardless of socioeconomic circumstance, the aim is to provide a safe online environment for children and protect their welfare while enabling them to develop a range of skills (e.g. Nansen et al., 2012). These mediation strategies include things like the conscious physical placement of computers in shared and visible spaces such as the living room rather than in the privacy of bedrooms, installing or running filtering technologies such as parental control software, checking the suitability of and approving which sites their young people can visit, supervising while their young people were using the computer, placing time limits on use, and discussing perceived dangers.

The literature categorises styles of mediation in terms of restrictive mediation, active mediation, and co-viewing or co-playing (e.g. Nikken and Jansz, 2006); that is, restricting media use, talking about media use, and viewing or sharing use respectively. Green, Holloway and Quin (2004) place these along a spectrum from a more authoritarian to a more empowering autonomous approach. It has been shown that these styles of mediation correlate to young people's age, with parents adopting more restrictive approaches for younger children (NetRatings Australia, 2005). While parents emphasise and encourage young people's Internet use for learning, and implement measures to support this, we found in the Screen Stories study (see: Gibbs et al., 2010; Nansen et al., 2012) that children often pursue playful uses or personal objectives, such as selective use of sites, including educational applications (e.g. Mathletics). These playful sensibilities and tactics demonstrated negotiation with adult mediation, management and agendas. Similar findings are supported in youth media literature, with young people using tactics of multitasking and minimising windows when parents look on (Shepherd et al., 2006), or by claiming educational value for a game (Livingstone 2009, p. 44). Here, young people's ICT use is often less about developing critical capacities, than about negotiating commercial, parental or educational restrictions in order to satisfy or achieve personal goals of use - largely for leisure or play.

From our observation of young people's use of ICT whilst on the bus, we noticed that they took advantage of what is ostensibly a less supervised and mediated space to, for example, view content that may be restricted at home, such as YouTube clips, or access social media sites that may not be allowed in other places (such as school). These activities, of which parents or teachers may or may not be aware, suggest that while the principal and general focus for adults in relation to child digital inclusion is supporting possibilities for education and protecting children from risk, for young people themselves inclusion is primarily about pursuing possibilities for play, entertainment and social interaction.The MYBus service demonstrates an awareness of the role and importance of social media in young people's lives, using Facebook to promote their services and build relationships with youth in the community: "In 2010, a Facebook page for the MYBus was set up. This allows youth outreach officers to update young people on the whereabouts of the MYBus and activities that are being planned. More than 100 young people from the Cardinia Shire are signed up as a MYBus 'friend'" (Cardinia Shire Council Community Services Unit, 2010).

The MYBus service provides a space for young people to use technologies outside of well monitored or poorly connected spaces. Thus in addition to responding to inadequate broadband connections in the home, the MYBus service serves to provide young people a form of digital inclusion at different times and locations, a way to navigate their Internet governance at home and school, to assist in developing a range of competencies or expertise, and digital literacy, which will be required to negotiate online environments as they develop.

Digital Mobility

Young people who live in areas that could be considered low socioeconomic areas don't have access to the Internet as parents can not afford it therefore love it when the bus visits their town as they can access it. Also families in these areas don't have the ability to afford a Wii or Playstation so young people love using these games on the bus (Anonymous Shire employee)

This quotation aptly summarises the role of MYBus in not only providing access to digital media and communications technologies, but also making the technologies mobile in order to redress the geographic, socioeconomic and technological inequities for young people living in urban fringe areas such as Cardinia. Many urban fringe areas are not well served by public transport and there is often a paucity of so called "third spaces" where young people can get together easily and safely. Many young people in Cardinia have reduced access to digital technology in their homes and by virtue of lower access to resources, in public spaces, whilst access at school is primarily focussed on educational purposes. As a result, these young people face reduced opportunities to use digital technologies for social purposes and to access general information - including information underpinning health literacy. As a mobile service, MYBus travels to many parts of the Shire reaching young people in areas that are geographically dispersed or disadvantaged, and thus not only supports access to health services for those who are less socially and economically advantaged, but also provides access to the Internet and other digital technologies, thereby countering inequities in digital participation and inclusion.

The contribution of MYBus illuminates two theoretical constructs that are increasingly recognised as social determinants of health: mobility and social capital. Spatial mobility has in recent sociological literature been identified as an increasingly critical characteristic of modern societies (Urry, 2007). This literature has revealed how mobilities operate both on a global scale through the movements of bodies, objects, capital, information and images and on a local scale through things like daily transportation or the movements of material things within everyday life (Sheller & Urry, 2006, p.1). Here, the capacity to move and the systems supporting individual movement have been increasingly recognised as an important aspect of social equity and participation. This capacity to move has been described through the concept of mobility capital, or motility, which is likened to other forms of capital..."another form of capital like its financial, cultural, and social counterparts that shape people's life courses" (Kaufmann and Widmer, 2006, p.124; see also: Kaufman et al., 2004). The idea of mobility capital has been proposed and situated in relation to social, adult, and family life (Kaufmann et al., 2004; Kaufmann and Widmer, 2006), yet our contribution is to commence developing a particular type of mobility capital for children and young people, especially as it emerges in geographically and digitally disadvantaged areas.

In this case, what has been described as mobility capital assumes a key role in more contemporary theorising about social capital in adults. Social capital in general refers to the extent, nature and quality of social ties that individuals or communities can mobilise in conducting their affairs (e.g. Zinnbauer, 2007), in ways that enhance social connections, supports inclusion and challenge exclusion. There are, however, two strands of theorising about social capital in relation to children and young people: the adultist and the sociology of childhood. Critiquing the adultist strand, Madeleine Leonard argues that the theorists Putnam and Coleman account for the relationship between childhood and social capital by concentrating on adults' stock of social capital and how effectively these adults transfer their social capital assets to their children, which they can "cash in" when they grow up. In keeping with much of sociology, Coleman and Putnam have little to say about children's existing usage of social capital. Moreover, they give little acknowledgement to how children's own agency and networks might facilitate the development of social capital among children (Leonard, 2005). The implication of the argument, that for children social capital is a by-product of their parents' relationships with others, is that their own social capital networks are rendered invisible (Ferguson, 2006).

By contrast, Virginia Morrow, an advocate of the new sociology of childhood based upon the work of the British social anthropologists Allison James and Alan Prout, argues that we need to move beyond psychologically-based models of childhood as a period of socialisation, and emphasise that children are active social agents who shape the structures and processes around them (at least at the micro-level), and whose social relationships are worthy of study in their own right (Morrow, 1999). In relation to the social capital debate, Morrow (1999, p.746) proposed that although Pierre Bourdieu did not explicitly discuss children's social capital, he left space for such a discussion by describing social capital "as rooted in the processes and practices of everyday life". When combined with the recognition from the new sociology of childhood that children possess agency, Bourdieu's formulation could explain how the micro-social worlds of children interact to produce social capital. For example, Madeleine Leonard drew on a combination of Bourdieu and the sociology of childhood to interpret findings from her study in Belfast to show how young people demonstrated agency and social capital independent of their families by initiating their own social networks and finding part-time work to benefit both them and their families (Leonard, 2005). Morrow (2000) argues that a distinctive feature of young people's communities is that they often constitute a "virtual'"community of friends based around school, town centre and street.

Morrow's concept of a virtual community provides a neat bridge between the social capital, mobility and digital inclusion literatures and our findings about the mobile MYBus in the fringes of Melbourne, Australia. These findings acknowledge that social capital is a factor operating in children's lives and relationships (Leonard, 2005; Morrow, 2000; Weller & Bruegel, 2009) and they add to the growing literature on children's spatial movement and independence that addresses the importance of mobility for the wellbeing of young people (for literature reviews, see: Garrard 2009; Thomson, 2009; Zubrick et al., 2010). Yet, these findings also amend understandings of social determinants of health to recognise the important mediating role of digital technologies. In relation to social capital, communication technologies are shown to be a resource to enable people to thicken existing ties as well as generate new ones (e.g. Licoppe, 2004; Davis et al., 2012; Zinnbauer, 2007). Mobile phones or email, for example, are used to stay better in touch and coordinate activities with friends and family members (Licoppe, 2004; Davis et al., 2012), making it possible to maintain relationships. Thus, Wyn et al., (2005) note that the Internet mediates, supplements and transforms social capital: it provides another means of communication to make existing social relationships and patterns of civic engagement and socialisation easier, but in this provision it also remediates it, amends how, where, when social interaction takes place.

Further, digital technologies have been shown to support mobility for families and children (see: Pain et al., 2005; Davis et al., 2012). Pain et al note, for example, that the contactability provided by mobile phones may help to alleviate parental fears, free children and parents from set deadlines, expand children's spatial ranges, empower young people to reclaim public spaces, and ultimately provide opportunities for children to move. In this case, digital technologies emerge in relation to spatial mobility as a resource for challenging young people's lack of mobility. Yet, in mediating both mobility and social capital, technologies do not simply operate as a means for enabling connectedness and inclusion, as without access to or skills with such digital resources, they can also operate to unevenly distribute advantage and disadvantage, and thus contribute to social immobility, inequality, or exclusion. The view that social capital is distributed unevenly and can act as a source of exclusion rather than cohesion emerges with Bourdieu (see Weller and Bruegel, 2009), and has been taken up in relation to mobility capital, where access to a range of factors that enable spatial movement to proceed has been to shown to vary (Kaufman et al., 2004). Here, mobility and social capital is not simply possessed by individuals, but formed through a range of physical contexts and social relations.

Our study of MYBus in Cardinia too suggests that young people on the fringes of urban areas face geographical and economic barriers to using digital technology for other than educational purposes. MYBus, as a mobile resource, provides access to digital technology and information to promote health literacy. As a result, children and young people are able to connect both in person and electronically in a child friendly environment. This mobile environment provides the opportunity for them to initiate links, gain access to information, and eventually develop mobility and social capital. The bus mobilises - in multiple senses of the word - technologies for young people whose location or mobility is disadvantaged. We argue that what we have identified through observing MYBus a version of social capital that can be labelled children's mobility capital because it relies on recognising spatial movement as a mode for supporting social connection. This particular capital is, however, not only mobile, but also digital. It can therefore accurately be labelled as children's e-mobility capital. This mode of capital is made visible by its lack in the lives of young people who are geographically isolated or who do not have adequate access to digital resources that facilitate movement and inclusion; but it can also be made visible by mobile interventions such as in the case of MYBus.

Conclusion

This paper has reported on a mobile youth service, MYBus, and analysed how the aggregation of digital media onboard MYBus not only assists in the provision of healthcare and health literacy, but also enables a broader approach to young people's wellbeing by providing mobile resources for digital access and participation. In particular, the paper has shown that the mobilisation of these technologies is significant for young people living on the urban fringe. We have developed the concept of children's e-mobility capital in relation to young people in order to theorise this technology mobilisation, and we have situated the mediating role of technologies for supporting mobility capital in relation to digital inclusion as a determinant of health and wellbeing. We have argued that an important factor in young people's digital inclusion, in addition to access and mediation, is mobility. This is evidenced by the kilometres travelled by MYBus, which not only enables youth engagement in health care, improving access to health information and support for less advantaged communities, but blends heath provision with new technologies and then mobilises these services and technologies to support opportunities for digital participation and inclusion for young people in less geographically and socioeconomically advantaged areas of the Shire. It may not address other mobility issues facing young people, such as public transportation, but it does nevertheless act to include those in more disconnected locations and their associated experiences of reduced mobility capital.

Our study cannot draw direct empirical conclusions about MYBus and health and wellbeing outcomes. It can, however, draw on more general findings from the social capital and urban planning literature that establish social capital as a determinant of health (Ziersch et al., 2005). Moreover, we know that social capital and social connections can be enhanced by approaches to urban and social planning that explicitly aim to thicken social connections, which in turn affects social capital and other determinants of health (Baum et al., 2011). On the basis of our analysis of MYBus and synthesis with theory, we therefore propose the need for further exploration of how social interventions can improve mobility, digital access and social capital for children and young people in order to reduce health inequities associated with geographical and digital disadvantage.

Future research should also move beyond the more traditional way of describing the unequal distribution of digital technology access and use between different groups in society as a "digital divide" implying a dichotomy of technology "haves and have nots" (Newman et al., 2010). Instead, the distribution of digital access clearly follows the socioeconomic gradient, which has been shown to be highly relevant by the World Health Organisation's Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (CSDH, 2008). We agree with the call by Newman et al (2010) to draw on contemporary public health literature to describe the socioeconomic differences in digital access and use as a digital gradient across the whole population, rather than simply a divide between those connected digitally and those not connected. Such nuanced approaches are likely to provide a thicker description of use and barriers in urban fringe areas that feature significant geographical variation, including in the case of Cardinia a mix of urban and semi-rural populations. Thicker accounts that describe technology use across geography and gradients of disadvantage are more likely to lead to practical and effective policies and programs to promote digital and health equity.