Accessibility Challenges Experienced by South Africa's Older Mobile Phone Users

- Professor, School of Computing, University of South Africa, South Africa. E-mail: vbiljja@unisa.ac.za

- Senior Lecturer, School of Computing Science, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK. E-mail:karen.renaud@glasgow.ac.uk

- Senior Lecturer, School of Computing, University of South Africa, South Africa. E-mail:vdyktj@unisa.ac.za

INTRODUCTION

It would not be unrealistic to claim that we are living through a renaissance resulting from the impact mobile telephony is having throughout the world, both developed and developing. This uptake is particularly noteworthy in Africa (Botha, Batchelor, Van der Berg, & Sedano, 2008; Jagun, Heeks, & Whalley, 2008). Kleine and Unwin (2009) report that Tanzanian students spend five times as much on their mobile connection as they are spending on food. Aker and Mbiti (2010) provide various examples of the beneficial impact mobile telephony has had on development in Africa. In terms of both numbers and reach, mobile telephony is the dominant form of telephony in developing countries (Jagun, et al., 2008). The reported impact is clearly profound and life-changing and, as such, constitutes the renaissance we refer to here.

This warrants further investigation into mobile telephony as a facilitating technology. The aim is to involve all members of the community, including the elderly, in mutually beneficial interactions. Researchers in Community Informatics study the mobile telephony phenomenon to improve the lot of previously neglected and marginalised communities, such as the elderly (Loeb, 2011). Although the elderly are likely to possess vast reserves of wisdom, we have not yet found an effective way to tap this resource for the benefit of the whole community. This is especially true in developing countries where many of the elderly are not literate. In bygone eras they would have transferred their wisdom verbally within small family units. As "sages", they were respected and consulted about difficult issues and asked to mediate in intractable situations. This is considered one of the few benefits of aging (Minichiello, Browne, & Kendig, 2000). Wolf (1998) refers to this concept as generativity: the old contributing to the lives of the young, enriching both generations in the process.

There is evidence that digital inter-generational interactions already occur in community centres in the developing world, and that this interaction delivers a range of benefits to their communities (Bailey & Ngwenyama, 2010). Modern urbanised society has weakened the role of the sage, and the rich resource of wisdom possessed by the elderly is relatively untapped. Furthermore, the elderly often feel excluded from society (Scharf, Phillipson, Kingston, & Smith, 2001). In developing countries, it may also be the case that the elderly are excluded from the global knowledge society (Thinyane, Terzoli, & Clayton, 2009). It is imperative for us to identify suitable mechanisms for capturing and preserving indigenous and experiential knowledge (Lwoga, Ngulube, & Stilwell, 2010) and for including the elderly in our communities and allowing them to benefit from the global knowledge society as well as themselves contributing. Andrews (1999), in arguing for the importance of acknowledging and valuing age, rather than ignoring it, quotes (Kohlberg & Shulik, 1981:72):

"If some aging persons do attain a greater wisdom, then among the most important things a student of aging could do is to clarify and communicate that wisdom to others."

In utilising the powerful affordances of mobile telephony, as a bridging and facilitating mechanism, there is one particularly pertinent and tough initial challenge to be confronted. Whereas the young are completely comfortable with mobile phones, and indeed consider them an indispensable accessory, the elderly often grapple with physical, cognitive and infrastructural challenges related to mobile phone usage (Gelderblom, Van Dyk, & Van Biljon, 2010; Neves & Amaro, 2012). The accessibility and usability challenges of mobile telephony, we will argue here, have the potential to deter the adoption of mobile phones, and thus the potential for knowledge transfer across generations, is curbed. Against this background the objective of this paper is to report on an investigation into mobile phone accessibility as pertaining to elderly South Africans. Applying action research methodology, the data was captured by university students who interviewed a cross-section of older mobile phone users across the breadth of South Africa.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. The literature review covers technology usage by the elderly and the pertinent accessibility and usability aspects thereof. This is followed by an explanation of the research design and data capturing. Finally, the results are discussed. We then highlight the insights obtained from this study regarding mobile phone accessibility for the elderly and explore the potential for facilitating inter-generational knowledge transfer.

RELATED RESEARCH

Information systems in developing countries (ISDC) research has developed an understanding of information systems innovation phenomena, mainly through its attention to social context and strategic concerns associated with socio-economic development (Avgerou, 2008). The impact of ICT on the emancipation of individuals and communities and involvement in the knowledge society are still limited, albeit less so with each passing year. There is general agreement that the use of mobile phones can have a positive effect on social connectedness, access to information, and social and civic participation (Loeb 2012; Neves & Amaro 2012). However, the elderly community has age-related impairments that can influence their use of their mobile phones. These can be classified as follows (W3C_B, 2012):

- Vision problems - reduced contrast sensitivity, colour perception, and near-focus, making the phone difficult to use.

- Physical weakness - reduced dexterity and fine motor control, making it difficult to press small buttons.

- Hearing difficulties - difficulty hearing higher pitched sounds and separating sounds, especially when there is background noise.

- Waning cognitive abilities - reduced short-term memory, difficulty concentrating including being easily distracted, making it challenging to navigate and complete tasks without making multiple attempts.

These issues overlap significantly with the accessibility needs of the disabled (Rogers, Sharp, & Preece, 2012). It is clear that accessibility issues can deter acceptance of a particular technology, no matter how potentially useful it is. Technology acceptance and adoption are key concepts in a broad field of research areas, including information systems, pedagogy, psychology and sociology, but each has a slightly different focus. Information systems research focuses on the factors that could influence the approval, favourable reception and on-going use of newly introduced devices and systems (Arning & Ziefle, 2007) and term this technology acceptance. Sociological studies take a macro-level approach, contemplating the purchasing decision as part of an adoption process that incorporates the user's acceptance or rejection, as well as their use of, technology (Haddon, 2003).

For the purpose of this study we are considering the acceptance factors from Information Systems (IS) but incorporating these into the adoption phases as advocated by (Renaud & van Biljon, 2008). We focus primarily on communities within a developing world context. Steinmuller (2001) points out that the strides technology makes are often gigantic. He argues that ICT has the potential for allowing the developing world to leapfrog some of the gaps between developing and developed countries to narrow the digital divide. Raiti (2007) warns that this leapfrogging process could easily neglect the small steps that are vital in encouraging technology acceptance and adoption. One cannot take lessons learned from developed countries and apply them, as is, to developing countries. Hence it is vital that we take the time to consider the acceptance factors, especially for marginalised and easily ignored sectors of the community, such as the elderly in developing countries.

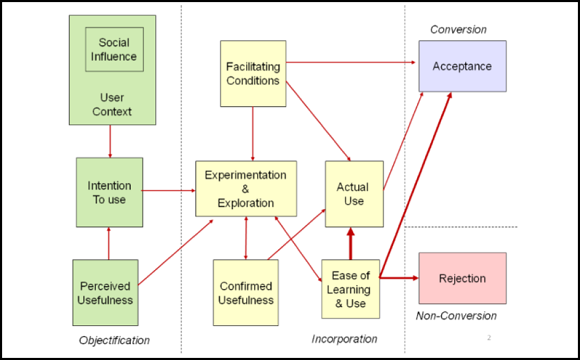

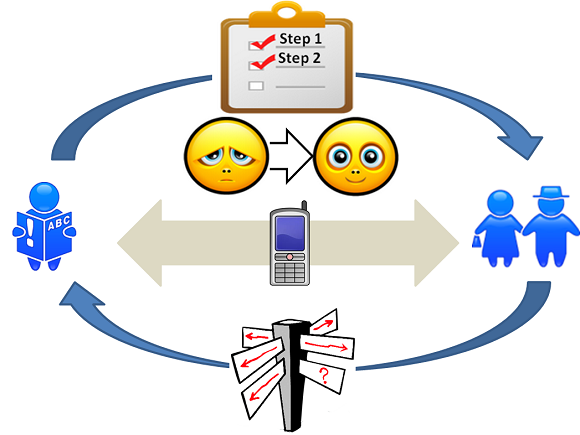

Traditional technology acceptance models, initially developed in the Western world, are based on the idea that users either accept or reject the technology and that such acceptance involves a predictable progression through phases such as appropriation (the process of possession or ownership of the artefact), objectification (the process of determining the roles a product will play), incorporation (the process of interacting with a product) and, finally, conversion (the process of accepting the technology) (Rogers 2003). Renaud and Van Biljon (2008) proposed the senior technology adoption model (STAM) based on an investigation of older mobile phone users in South Africa. Drawing on the model of Silverstone and Haddon (1996), STAM presents the adoption process as three-phased: objectification, incorporation and conversion/non-conversion. The STAM model is illustrated in Figure 1. Note that, contrary to other adoption models such as Rogers (2003) and Silverstone and Haddon (1996) there is no appropriation phase during which the person contemplates buying a phone and gathers information about available products. The probable reason is that elderly developing world users we studied typically received their phone as a gift (Renaud & van Biljon 2008); a tendency confirmed by a subsequent South African study (Gelderblom et al., 2010).

Furthermore, it is important to note that acceptance is a necessary precursor to adoption but other factors come into play post-acceptance. These are currently not reflected in STAM.

Despite this limitation, STAM does provide a framework for considering those factors which can derail attempts to use mobile telephony for inter-generational knowledge transfer. Some aspects to note:

- Intention to use is determined by perceived usefulness as well as by social influence (i.e. adult children urging elderly parents to use the phone). Family relationship plays a critical role in supporting older adults' psychological well-being, morale, and life satisfaction (Chen, Wen, & Xie, 2012).

- The model emphasises the role of facilitating conditions (e.g. financial constraints and infrastructure) which can derail acceptance. The importance and impact of this aspect on users is argued for convincingly by Pather and Usabuwera (2010), which confirms its powerful influence as depicted in this diagram.

- A poor experimentation and exploration experience may lead to the perception that the technology is difficult to use and this is likely to result in rejection, unless the usefulness and facilitating conditions are powerful enough to discount this poor experience.

- Ease of learning is regarded as a key determinant of actual use that impacts acceptance or rejection. Note that rejection can be based on actual use or it can even happen in the ease of learning & use phase (even though this is not explicitly shown on the diagram).

A related finding is that although older people continue to use their mobile phones, they sometimes do not whole-heartedly adopt them. This is echoed by Conci, Pianesi and Zancanaro (2009) who found that many older people do not go beyond their initial approach to the mobile phone, even after years of frequent usage. Non-adoption is an option often exercised, quite reasonably, by the elderly (Linton, 2012).

The dependency of actual usage on usefulness was found to be stronger than the dependency of actual usage on ease-of-use (Venkatesh & Bala, 2008) . This is confirmed by the fact that elderly mobile phone users often continue to use the device for communication purposes despite severe and debilitating accessibility challenges (Renaud & van Biljon, 2008). In developing world contexts, the mobile phone is often also used for both communication and organisation. The importance of the device for communication is more pronounced in an African context since rural users often have little access to any other means of remote communication (Van den Berg, Botha, Krause, Tolmay, & van Zyl, 2008). This confirms usefulness, but does it necessarily lead to full acceptance and consequent adoption? Donner (2010) acknowledges the issue of barriers to universal mobile use in developing countries due to cost constraints, linguistic or skill limitations. He argues that the prolific mobile phone sales, despite these barriers, suggest that the benefits outweigh the costs related to the difficulties.

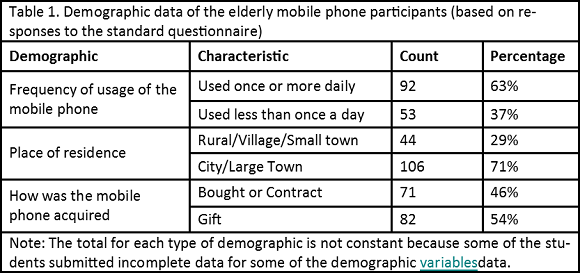

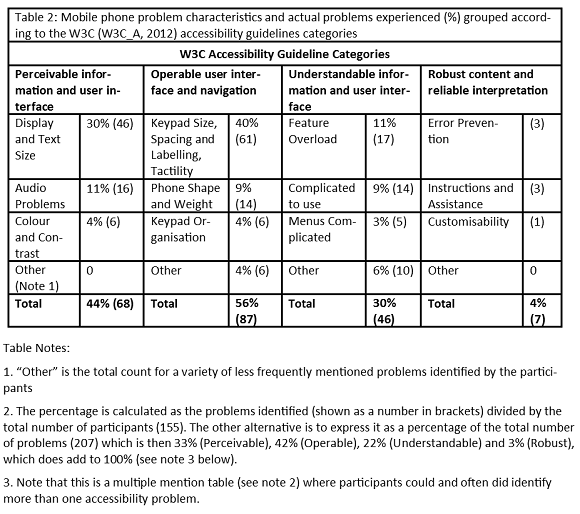

Developing world mobile phone users need to move to full acceptance for inter-generational knowledge transfer to flourish. We consider full acceptance to be a function of (i) frequency of use (see Table 1), (ii) the number of other features used (such as text messaging or camera), and (iii) the number of usability and accessibility problems reported (see Table 2). The latter aspect will impact on the first two, showing that accessibility and usability (as explained below) play a pivotal role:

- Accessibility is defined as the degree to which an interactive product is accessible by as many people as possible and the ability to access the functionality and possible benefit, of some system or entity (Rogers, et al., 2012). Concerning mobile devices, Traxler (2005) describes an accessible device as one that meets the needs of users with specific learning difficulties or disabilities, such as visual, hearing, speech, mobility or manual dexterity impairment. The W3C proposed guidelines for mobile phone accessibility for older people, are designed for the use of the web on mobile phones but also cover general mobile phone accessibility as discussed in the section on research design (W3C-A).

- Usability is the extent to which a product (e.g. device or service) can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use (ISO 9241-11, 1998). Interaction design has evolved since 1998; the latest version of the international standard for human-centred design uses the term user experience rather than usability (Rogers, et al., 2012). The International Organisation for Standardisation's current ISO standards (ISO 9241-210, 2010) on human-centred design describes user experience as: "all aspects of the user's experience when interacting with the product, including all aspects of usefulness, credibility, accessibility and desirability of a product from the user's perspective".

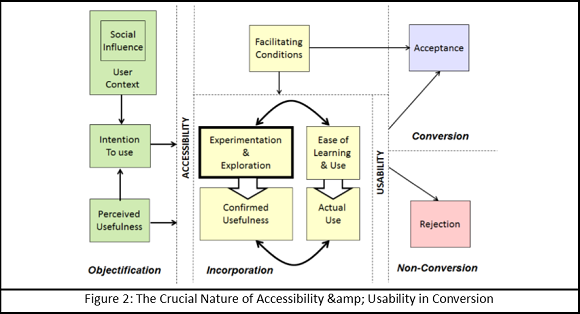

Usability has accessibility as one of its essential components (Reece, 2002), and we thus concentrate on accessibility since it is a precursor to use. Mobile phone interaction is often designed for the average (and young) literate user, yet people of all ages vary and designs seldom suit or meet the needs of any one individual completely (Gill & Abascal, 2012). The mobile phone user is expected to adapt to the interaction and those unable to do this may be excluded from using a product or service. However, if mobile phones present insurmountable accessibility barriers it is likely that the user will not even embark on the experimentation and exploration phase and will not be able to experience actual use, determine ease of learning & use, or confirm the usefulness of the device. Figure 2 demonstrates the pivotal nature of the experimentation and exploration phase, which, together with ease of learning, provide the gateway to confirmed usefulness, actual use and eventual acceptance.

Here we focus on accessibility, which could prevent the elderly mobile phone user from even entering the incorporation phase. Once the accessibility barriers have been cleared, usability becomes important (Reece, 2002). If there are no accessibility barriers, and they do enter the experimentation and exploration phase, usability issues could easily trip them up, and this would affect the decision to accept or reject. Therefore accessibility is depicted as the barrier to the incorporation phase and usability as the barrier to the conversion phase. Oreglia (2010) studied the lives of six Chinese rural-to-urban migrants. She notes that there is a steady progression "from access, to use, to effective use" in terms of technologies. This highlights the importance of accessibility. In terms of accessibility barriers, we need to bear in mind that older people give up more easily than younger when using new technology so any barrier's negative effect is magnified for this group (Giuliani, Scopelliti, & Fornara, 2005).

RESEARCH DESIGN

Our research philosophy is interpretive. Based on the mapping between the properties of this study and that of action research, as proposed by Oats (2009) and presented in the next paragraph, this study can be classified as action research. Action research is characterized by six properties (Oats, 2009). The extent to which these properties were applied is now discussed:

- Concentration on practical issues: The accessibility and use of mobile phones is a real world problem for the elderly.

- Emphasis on change: The student researchers explored mobile phone usage, usefulness and ease of use issues and also taught the participant to use a new function on their mobile phone, which allowed them to gauge ease of learning.The intervention, of teaching the participants to use a new function, was geared towards knowledge transfer for change and improvement of the user's situation.

- Collaboration with practitioners: The students collaborated with the elderly who can be seen as the practitioners. The involvement of students as researchers in community informatics is not novel. Turpin, Phahlamohlaka and Marais (2009) argue for introducing students to the multiple perspectives approach (MPA) that covers computer science and information systems aspects and they also applied the MPA towards developing students as future ICT4D 2.0 champions. Their study also involves students as analysts and cultural interpreters.

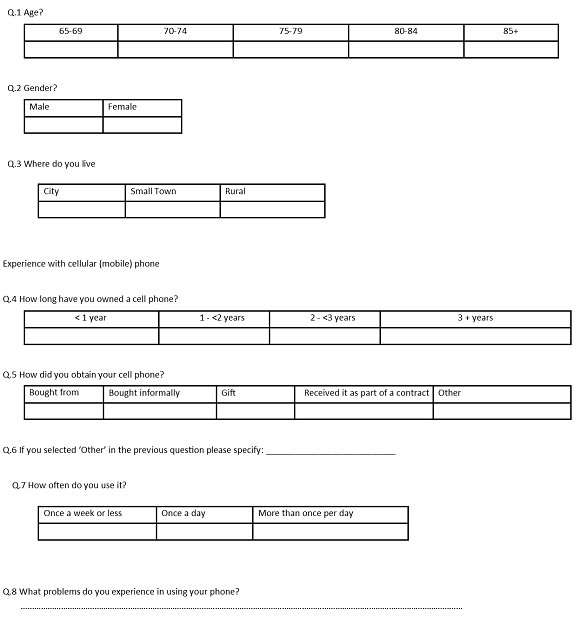

- Multiple data generation: The data was captured by computer-literate honours students over a period of two years, each of whom interviewed the older, less computer-literate mobile phone users (people above the age of 65), to explore mobile phone accessibility and knowledge transfer aspects of mobile telephony. The interviews were structured according to a questionnaire that consisted of fixed-response questions, open-ended questions and a teaching and learning activity.

- Action outcomes plus research outcomes: The action outcome was to transfer knowledge and skills on the use of the mobile phone. The research outcome was the insights abstracted from the data on mobile phone accessibility.

- An iterative cycle of plan-act-reflect: This property did not apply to the research done since there was only one formal cycle but informally the students and their elderly participants could and possibly would engage in further discussions on mobile phone use.

The fieldworkers were all enrolled for a Human-Computer Interaction module, specialising in accessibility issues and including a section on challenges faced by the elderly. They carried out the research as one of the two assignments in the module. They could choose any mobile phone owner aged 65 or older who was willing to participate. Based on the report most interviewers chose family or friends but this was not a universal tactic. The questionnaire, provided as Appendix A, outlines the issues covered and the order of the data capturing.

The student researchers submitted reports which reported on responses to the questionnaire. They also provided general observations on mobile phone usage by the elderly and specifically on the teaching intervention. In some cases students provided a detailed account with rich insights and quotes while others simply responded to the questions. The data was extracted from the student reports and collated in electronic format for processing.

Donner & Toyama (2009:5) argue that: "Qualitative inquiry is the key to unpacking the complexities of technology use in the rich contexts of the home, the community, the workplace". This, however, does not disaffirm the value of quantitative data and analysis and therefore we captured both quantitative and qualitative data and used the quantitative analysis to inform the qualitative inquiry. The novelty of this study lies in the fact that the needs of the elderly mobile phone user are captured through the lens of a squad of younger "researchers". There are a number of reasons for doing this, which can be summarised as follows by:

- Firstly, in order to conduct valid inter-generational research it is essential to involve participants from different generations and to record their different perspectives so as to be inclusive (Donner & Toyama, 2009).

- Secondly, as Toyama and Dias ( 2008) point out, direct interaction with the target community is essential in order to uncover particular issues and challenges.

- Thirdly, Unwin (2009) cautions that, in order to understand the economic, social, political and ideological factors influencing ICT4D initiatives, it is crucial to speak to a wide variety of potential users before implementing a mobile telephony based ICT4D initiative. Our researchers were able to question a cross-section of both urban and rural South African elderly, thus satisfying this requirement.

- Finally, Krauss and Turpin (2010) make a strong case for the role of the cultural interpreter in ICT4D research. Our student researchers implicitly took this role, interviewing the older person in their own cultural setting, deciphering and interpreting and finally reporting on their findings.

RESULTS AND FINDINGS

The 137 interviewers captured data from 155 participants over a period of two years. They recorded their findings in report format, which was submitted to the authors to support meta-analysis.

Accessibility

In terms of the digital divide, mobile phone accessibility undeniably impacts knowledge transfer across generations. In order to address the situation, we first needed to understand it. Therefore the first objective was to investigate mobile phone accessibility as experienced by the elderly and also to get some idea of their actual usage. Table 1 highlights some important facts about the profile of 155 participants. Twenty nine percent lived in rural areas or small towns and the rest in cities or large towns. More than 50% received the phone as a gift. This confirms the importance of the social influence.

In terms of actual usage, 37% did not use their phones on a daily basis, which seems to indicate that they have not yet integrated it into their daily lives and thus they have not progressed to acceptance as based on daily usage.

Table 2 shows that when analysing the data according to the W3C main accessibility guidelines categories (namely operable, perceivable, and understandable information and interfaces), it was found that most responses focused on problems with the size (namely the display size, display font size, button size and spacing, and the button font size), the sound (not loud enough) and complexity aspects (too many functions, complicated to use, and poorly designed menu structures). Perceivable problems were identified from 44% of the participants, operable problems from 56% of the participants, and understandability problems were identified by 30% of the participants.

Many, if not most, of these senior citizens have overlapping needs, and the responses reflect this in that many identified both visual (perceivable), operable (dexterity), and understandability (cognitive) problems with their mobile phones. This is confirmed by the total count of 207 identified problems from the 155 participants i.e. about 1.4 problems stated per participant on average. Note that this count represents the problems stated during the interview, so there could be more problems that were not verbalised at the time. The logical fit with mobile phone characteristics, as presented in Table 2, indicates that although W3C accessibility principles (W3C_A, 2012) were aimed at mobile phone access to web interfaces, they are, with minor tweaks, also applicable to the analysis of accessibility problems of mobile phones.

The main insights are therefore that:- All users experienced at least one accessibility problem. This is based on their individual responses with an average 1.4 accessibility problems per phone.

- Physical accessibility problems (which are the sum of the operable and perceivable categories in Table 2) account for (87+68)/155 i.e. effect, on average, on elderly users.

- Cognitive problems accounted for a minority of the problems identified in Table 2. However, their impact and severity cannot be discounted since some participants, due to physical accessibility problems, may have been unable to access functionality on the device at which pointcognitive problems would have become evident.

The main limitations of this survey is that the student's relationship to the elderly participant and the participant's involvement in the selection of the phone was not comprehensively captured. The next section discusses the inter-generational knowledge transfer.

Knowledge Transfer

Besides capturing the data using the questionnaire we also investigated the elderly person's mobile phone usage through the eyes of the younger researcher. This is in line with the action research goal of multiple data generation and was achieved by asking the younger person to report on a training session during which they taught the participant a mobile phone function. The function was selected by the elderly person in consultation with the student. There was no prescribed teaching methodology or reporting format. The students were required to report on the function they taught the older person and to report on their own reflections on the process and outcome. Note that our scope is limited to the differences in their expectations of technology usage and we did not undertake any analysis of the mental or pedagogical models involved. The older participants selected a variety of functions, based on their familiarity with their own phone. The five most often selected functions were the sending of text messages (33%), using the phone camera (13%), using the internet and email (10%), sending multimedia messages (7%) and setting alarms and reminders (7%). This indicates that alternative communication functions are popular (the elderly person could choose which function to be taught) as well as functions that may help them to remember to do certain activities.

We also used the narrative accounts as reported by the interviewer, which reflects how the younger person viewed the learning experience. We used this to identify similarities and contrasts. Interviewers were not instructed to comment specifically on the issue. Those who did were clearly sufficiently captivated by their observations and experiences to report them and these reports thus contain valuable insights.

Insight Into Skill Transfer From Young to OldA number of recurring issues emerged during the analysis. Here they are enumerated and illustrated with a quote or explanation:

- Emotional (reactions based on fear): The first task was to overcome the fear of the subject. The initial reaction was to question why they needed messaging as they could speak with a person if required. This was followed by the fear of breaking the phone.

- Cognitive (reactions based on illiteracy): "Mrs *** on the other hand she doesn't know that much about cell phones but she has a natural mind and sharp memory on to how to navigate her cell phone; Interesting enough for her, I had to use a stepwise model; like 1 click menu, 2 go to setting and then count 5 times click OK then you are on the Bluetooth. Even though the menus make no sense to her but the sound and the steps made her get it very quick. I showed her 4 times and she is a master on it."

- Cognitive (based on inadequate mental models or information overload). "It was noted that that subject seemed to learn how to get to the text message composer screen by rote, i.e. "button, down, button, button", instead of reading the menu text and selecting a specific option. This had the disadvantage that if she pressed the wrong button, she would get lost and had to start again." This led to a preoccupation with a sequence of steps rather than comprehension of the entire process.

From the students' reflections on their experience of teaching older people to learn a new function on their phone, in light of their own learning experiences, the following differences emerged:

- Reluctance to Experiment: The younger generation has more confidence in their ability to use technology and found it remarkable that people actually fear breaking the device.

- Self Blame: The younger generation expects more from technology and attributes problems they experience to the physical and cognitive design of the device rather than to themselves. The elderly were more likely to blame themselves when they experienced problems.

- Learning Approach: The younger user has a more holistic approach to understanding and using technology and were fascinated by the elderly's inclination to rote learn procedures without understanding the interface or gaining an overview before focusing on minutiae.

- Mental Models: The technology and metaphors that the students used to explain the task was foreign to the older generations, i.e. they did not have the same mental models. Interviewers found themselves having to moderate their use of terminology which they would have used unthinkingly with their contemporaries.

DISCUSSION

The findings demonstrate sustained use of mobile phones despite significant and disabling accessibility and usability problems. This confirms the findings of Gelderblom et al. (2010), who noted increased frequency, depth and breadth of use. This can only be explained by considering the prominence of the mobile phone, as an essential communication tool, in developing countries. This means that utility and usefulness trumps accessibility issues and usage difficulties. Many people (37%) do not use their mobile phones on a daily basis. They do not appear to have whole-heartedly accepted their phones or integrated them into their daily lives. This warrants further consideration of the accessibility and usability barriers. The goal of accessibility has been addressed by standardisation organisations who define accessibility guidelines. While providing useful criteria, these cannot be used in their original format for our purposes since the elderly users mostly do not have the differentiated knowledge or vocabulary to articulate their requirements, limitations and expectations at the necessary level of detail. Therefore the data was extracted from the participants' reported accessibility problems noted in response to question 8 in the questionnaire (see Appendix A) and then categorised according to the W3C criteria. Based on these findings, the results were summarised in terms of three insights regarding mobile phone accessibility in developing countries, namely:

- All participants experienced accessibility problems. (All reported at least one classic accessibility problem)2.

- All were affected by physical accessibility problems (the sum of operable and perceivable categories).3.

- Cognitive problems accounted for the minority of the identified problems but that may be a consequence of physical accessibility problems which bar the elderly from using more than the basic functionality. In this case cognitive problems are not experienced simply because of limited use.

Note that our findings confirm the W3C guidelines for mobile interaction (W3C_A, 2012). As explained, our data was derived from participants' qualitative responses and then categorised to be comparable to the W3C criteria. Therefore we present these as insights rather than guidelines. Due to the cost of speciality phones and the practice of handing down phones to relatives when the contract expires, the marketing of specifically-designed phones may not constitute a solution in developing countries. Therefore the drive towards universal usability initiated by Schneiderman (2001) where devices are designed to be accessible to everyone, instead of a specific group, remains a useful initiative.

Studies in community informatics have provided guidance on appropriate methods of ICT instruction for older persons (Loeb, 2011). Traxler (2007) warns that attempts to develop the conceptualisations and evaluation of mobile learning have to recognise that mobile learning is personal, contextual, and situated. Although this intervention may be at the bottom end of the scale of what is understood as mobile learning, it carries the same complexities. Therefore it is problematic to generalise but the findings do provide insights into the differences between the expectations for knowledge transfer and are thus presented as insights for those interacting with the learning elderly user. Based on our analysis, which was augmented by the reported research of Saunders (2004), Prensky (2001) and Hawthorn (2000), we contend that the training should:

- Be Patient and Reassuring

- Overcome fear of breaking the device.

- Do not rush the participant and answer all questions.

- Allow participants to learn at their own pace.

- Provide stepwise instruction:

- Provide only one way to achieve a task: no multiple paths and no complicated menu structures.

- Provide need-to-know information only - anything extra will distract.

KNOWLEDGE TRANSFER

Based on a study of information and communication technology projects in India, Walsham (2010) concludes that ICTs are potentially important contributors towards development for developing communities but only through their integration in wider sociotechnical interventions. Gomez and Pather (2012) proclaim the importance of the intangible benefits of ICTs in development, including empowerment, self-esteem and social cohesion. Leikas, Saariluoma, Rousi, Kuisma, Vilpponen (2012) argue that technology for older adults should support their strengths and enable their full participation in society. They also refer to the know-how the aged possess (what we call "wisdom") and urge that this should be utilised by society as a whole.

There is reason to believe that the mobile phone is particularly suited to knowledge transfer between generations, certainly in familial relationships. Fildes (2010) reports on how Sugata Mitra has established a "Granny Cloud" to achieve this kind of knowledge transfer in the UK and Italy. We argue that this may work equally well in developing countries. Neves and Amaro (2012) studied the use of ICTs by the elderly in Lisbon. One of their participants specifically referred to the phone's ability to support inter-generational communication. Would the elderly want to share their wisdom and participate in such a community? Related research into online communities, and the social values the elderly attach to them, include the importance of "a community that shares information" (Burmeister, 2012). This raises the question of giving advice to people outside their family. McLure and Faraj (2012) studied why people help those they do not know. They found that people participated out of community interest, in expectation of reciprocity and because they consider it pro-social behaviour.

Mitra and Arora (2010) argue that this kind of inter-generational learning environment cannot flourish without appropriate care being taken in setting it up, and in enforcing particular constraints. Thus technology, while having the potential for being a great facilitator and emancipator, can also act as a brake, or deterrent, if not designed with accessibility in mind.

CONCLUSION

The main objective of this study was to investigate mobile phone acceptance by the elderly in South Africa, as impacted by mobile phone accessibility barriers. To this end we firstly investigated accessibility from the perspective of the older mobile phone user. Secondly, we reported on the usage of the phone, and observations made by interviewers while training the older adult to do a new task on their phone.

In conceptual terms, our study confirmed the need to understand mobile technology from the perspective of the user and the wider community. That may seem a naïve statement of the obvious, but the implications for developing communities are not always acknowledged. The accessibility movement's focus has been continuously to enhance and extend the capabilities of the individual. ICT can also play to the strengths of the community and support community building endeavours. For example, the young can train the older members of the community to use mobile phones. If done appropriately, it may also pave the way for knowledge transfer from the older community members to the younger. This can only be achieved once accessibility problems have been resolved.

The contribution of this paper is the exposition of insights on mobile phone accessibility for the community of elderly mobile phone users in developing countries. The findings provide new insights into the differences between the generations in terms of challenges for knowledge transfer. Based on the lessons learnt from a successful ICT4D project (Romijn, 2008), we know that the solutions have to emerge from the community, rooted in the social and cultural context of use. Therefore future research will take these insights into account when creating the next step of the project where a procedure for incentivising knowledge and wisdom transfer between older and younger members of the community will be devised. The ultimate goal is to break down existing barriers to support and encourage mutually beneficial inter-generational knowledge transfer.

REFERENCES

APPENDIX A

Interview procedure:- Identify at least one research subject who is over 65 years of age and owns a cellular phone. You should preferably include three subjects in your study, but we will accept it if you use only one.

- Use the questionnaire given below as starting point to conduct a limited study on the subjects' interaction with their cellular phones. You have to include all the questions in the given questionnaire, but you may add any questions that you think may contribute to the study.

- Identify a function on the cell phone that the

subject has never used (if you use more than one subject

you should preferably teach them the same or a similar

function). Teach them to use the function and gather

information to answer the following questions (or any

other questions that you want to add):

- Were you successful in teaching them to use this function?

- If yes, how long did it take before they could use it?

- How many times did you have to demonstrate or explain the function before they were successful or gave up?

- With which specific aspects of the function did they have problems, if any?

- Will they use the function in future? If not, let them explain why not.

Demographic information