Impact of Mobile Phones on Integration: The Case of Refugees in South Africa

- PhD student, Department of Information Systems, University of Cape Town, South Africa. Email: kaskymiami@yahoo.fr

- Associate Professor, Department of Information Systems, University of Cape Town, South Africa. Email: kevin.johnston@uct.ac.za

1. INTRODUCTION

The integration of refugees into the host country, believed as having the potential to solve their exile related issues (Fielden, 2008), has become a much debated topic. While there appears to be little consensus concerning refugee integration strategies and policies that are developed in different ways in different countries (Fielden, 2008), to date in the developing world there are insufficient empirical studies on the impact of mobile phones on refugees' integration.

Social integration is defined as the "maximum involvement and participation of each member of society in social activities" (United Nations, 2008, p. 2). It has been suggested that Information and Communications Technology (ICT) has the potential to promote refugee integration (Cachia et al., 2007). However, it is argued that in developing countries the adoption of ICTs is made difficult by contributing factors such as high costs, lack of mobility, limited electricity, and inadequate skills (Chigona, Beukes, Vally & Tanner, 2009; Sinha, 2005). Mobile phones are claimed to provide a solution to these challenges since these are quickly becoming affordable, germane and accessible tools to many poor communities (Aker & Mbiti, 2010). Mobile phone is arguably the most ubiquitous modern technology as it's usage has introduced a range of new possibilities for economic development, political activism, and personal networking and communication (Kreutzer, 2009; World Bank, 2012), and is thus claimed to have a positive influence on social integration (Cachia et al., 2007). However, there is need for such claims to be subjected to rigorous research, and that constitutes the aim of this study.

A review of literature across disciplines has shown that the study of mobile phone use by refugee communities has had minimal attention (Leung, L. 2011). The research question that guided this study was: How does the use of mobile phones by refugees in South Africa impact on their integration? The objectives of this study include exploring mobile phone usage patterns among refugees in South Africa, as well as the main communication challenges they experience; investigating whether the use of mobile phones has an impact on refugees in terms of social, economic, and political participation; and, exploring how mobile phone usage affects refugees' social integration in South Africa.

This study focused on refugees in South Africa, a country in which the mobile phone market has seen a rapid uptake with the penetration rate estimated over 100 percent (World Bank, 2012). It is estimated that the prepaid calls system or pay-as-you-go is the main reason for such high level of growth and the driver of the entire South African mobile phone market (Chigona et al., 2009).

Although South Africa is considered as one of the largest recipients of refugees in the world (Bourgonje, 2010; UNHCR, 2007) in South Africa the law makes no provision for refugee camps. Refugees choose to settle in urban centres where particular conditions they desire are more readily available such as income-generating opportunities, education, adequate medical care and favourable climatic (Kobia & Cranfield, 2009; UNHCR, 2009). Nevertheless, in South Africa discriminatory practices and attitudes continue to be manifested against refugees who are denied rights to critical social services (Gordon, 2010), and are uniformly victimised in violent practices (Vearey, 2012). In South Africa, there is confusion between the terms refugees and asylum seekers (CoRMSA, 2011). For the purpose of this study, the term 'refugee' was used to refer to those who have formally been granted refugee status, as well as those who are seeking refuge. The focus was on refugees from the major African countries, and from countries not considered by the South African Department of Home Affairs (DHA) as primary refugee producing countries as in December 2005 (Landau, 2011).

Using a social integration framework, this study explored the potential of mobile phones to enhance the integration of refugees. The findings of this study make two contributions. Firstly, to the Information Systems field where little has been done using a social integration approach to determine the impact of technology on social integration. Secondly, to practice, since the findings serve to inform various stakeholders on the success and limitations of mobile phones as a tool for enhancing refugees' integration into a host community.

This qualitative study uses a sample of 29 respondents who spanned a range of selection criteria. Although this sample is not big enough, the findings of this study are relevant as they identify mobile phone usage patterns, and critical intervention areas to facilitate communication and social networks. These contributions respond to the call from the United Nations to encourage ICT researchers to contribute to the promotion of social integration, particularly for disadvantaged and marginalised groups (United Nations, 2007). This study is crucial since circumstances are adding to the numbers of refugees, and South Africa is likely to attract more and more of those refugees (CoRMSA, 2011). At the same time, refugees are the daily objects of discrimination with the destructive consequences to both nationals and non-nationals in South Africa (Landau, 2008).

The remainder of this paper is divided into four major sections. Section 2 provides a literature review on the status of refugees in South Africa (2.1), mobile phone usage in South Africa (2.2), and social integration (2.3). In Section 3 the social integration theoretical framework is described, Section 4 details the methodology, while Section 5 provides the analysis and implications, followed by the conclusion in Section 6.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Status of Refugees in South Africa

Reports show that in 2009 South Africa was the main destination for new asylum seekers worldwide and has thus rapidly evolved into one of the largest recipients of asylum seekers in the world (UNHCR, 2010). This trend will become more pronounced as several African countries are experiencing ethno-religious conflicts, and socio-political and economic instability (Crush & Ramachandran, 2010). Another contributing factor is the striking disparity in living standards and economic development between South Africa and other African countries (Naudé, 2008).

Following its first democratic elections in 1994, South Africa acceded to and ratified several treaties relating to forced migration and refugee protection (Gordon, 2010; Kobia & Cranfield, 2009). The 1996 South African Constitution (the Bill of Rights) guaranteed fundamental rights to all who are resident in the country, including refugees and asylum seekers (Landau, 2011). Refugees are issued documentation by the South African government that grant them employment rights. However, the legitimacy of this documentation remains unrecognised by most of employers (Landau & Kabwe-Segatti, 2009). The literature shows that, generally refugees face particular challenges throughout their exile lives (O'Mara, 2009). Most of time refugees have lost all their assets on their arrival in the host country, do not enjoy any property rights, may have communication challenges and may not possess the required knowledge and skills to survive in the new country - frequently they lack supportive social networks (Buscher, 2003).

In South Africa refugees are marginalised and deprived of their dignity (Cejas, 2007; Landau, 2008). As such, refugees face multiples obstacles in accessing social services they are entitled to by law. For example: in educational services, it has been found that "close to one third of school age refugees' children are not enrolled in schools" (Landau & Kabwe-Segatti, 2009, p. 41). In health services, refugees struggle to access emergency and basic health services due to the unwillingness of some staff members (Vearey, 2012). In housing, landlords and rental agencies hesitate to contract with refugees due to doubt over their papers' legitimacy (Landau & Kabwe-Segatti, 2009).

Refugees do not receive any kind of institutional assistance or financial support from the South African government (Cejas, 2007). Reports show that, compared to citizens, refugees in South Africa are more likely to be vulnerable to poverty and violence as they live in poor housing conditions and have minimal access to services (Duponchel et al., 2010). Despite this, many of them have demonstrated entrepreneurial spirit to solve problems, innovate and adapt (Krause-Vilmar & Chaf?, 2011). It has been found that "75 percent are economically active, while many are engaged in a multitude of simultaneous livelihood strategies" (Krause-Vilmar & Chaf?, 2011. p.1). However, xenophobic discourse in South Africa constructs refugees as a threat to the economic, social and cultural rights and entitlements of citizens (Matsinhe, 2009; Vearey, 2012). Refugees are typecast as "bringers of disease, crime and a variety of other social ills" (Crush, & Ramachandran, 2010. p. 216). It has been found that the majority of South Africans do not welcome foreigners, especially 'black' foreign nationals from African countries (Crush, 2012; Gordon, 2010). Such widespread anti-immigrant sentiment cuts across virtually every socioeconomic and demographic group (Gordon, 2010). This situation led to xenophobic attacks against refugees in May 2008, violence that spread nationwide and resulted in the deaths of more than 60 people and the displacement of some 46,000 others amid mass looting and destruction of refugee-owned property and businesses (UNHCR, 2009). This large-scale attack marked the latest development in a long series of violent incidents victimising refugees in South Africa (Crush, 2012).

Recently, however, refugee issues have begun to preoccupy the South African government, religious communities, as well as local and international Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs). Addressing barriers to refugee integration in South Africa has attracted a number of scholars, journalists and activists (Matsinhe, 2009). This research is part of that trend, and seeks to explore the impact of technology on the lives of refugees in South Africa. Mobile phones point to one solution due to their ubiquity. Leung (2011) suggests that for refugees, a mobile phone is the most critical technology in term of availability. However as Donner, Gitau and Marsden (2011) argue, in developing countries little is known about how people differentially use mobile phones. This paper continues with the review of the use of mobile phones in South Africa.

2.2 Use of Mobile Phones in South Africa

As in the rest of Africa, the introduction and growth of mobile phone services has been spectacularly successful in South Africa (Cellular News, 2009) where mobile phone penetration rate had exceeded 100 percent and is expected to increase substantially (World Bank, 2012). In South Africa, where mobile phones have become the most easily accessible and convenient way of offering services (Cellular News, 2009), an understanding of their usage is crucial. Mobile phones are increasingly being regarded by many as an extremely potent tool, a solution for social and economic development in developing countries (Dinez, Albuquerque & Cernez, 2011; Heeks & Jagun, 2007). Widespread mobile phone usage has introduced a range of new possibilities for economic development, political activism, and personal networking and communication (Kreutzer, 2009).

Literature shows that, apart from creating new sources of income and employment, mobile phones provide vital links between refugee populations and their families, and provide a tool to enable refugees to become self-sustainable (Diminescu, Renault & Gangloff, 2009). Van Biljon & Kotzé (2008) found evidence of the impact of social influences such as social pressure from other individuals and groups, and motivational needs such as nervousness and enthusiasm as being among the factors affecting the use of mobile phones. Other relevant factors included job status, occupation and income, facilitating conditions such as cost, security and connectivity, and perceived usefulness (Van Biljon & Kotzé, 2008). These influences have relevance in explaining and understanding the use of mobile phones by refugees.

In South Africa, mobile phone subscribers can access a mobile network either through a contract or as a prepaid service. The prepaid service is a useful alternative to a contract where the subscriber is required to have a good credit history and a regular income to qualify (Chigona et al., 2009). Thanks to the prepaid service plan, refugees in South Africa own mobile phones since it is difficult by means of a contract due to a lack of formal documents. The documentation issued to refugees by the South African government does not have the requisite thirteen-digit identity number, required for most contracts. However, unlike a mobile contract package where the customer has the opportunity of having modern mobile phones, most prepaid customers, including refugees, posssess mobile phones which may not have internet capabilities (Chigona et al., 2009).

Reports have shown that the developing countries are increasingly well situated to exploit the benefits of mobile communication (Donner et al., 2011; World Bank, 2012). However the use of mobile phones by refugees in developing countries had had minimal attention (Leung, 2011). Little is known about the impact of mobile phones usage on the integration of refugees in developing countries.

3. SOCIAL INTEGRATION THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Social integration is a complex concept which is often given widely different meanings (Ager & Strang, 2008; Atfield, Brahmbhatt & O'Toole, 2007). It is generally aimed at promoting societies that are safe, stable, tolerant, just, where diversity is respected and all people participate with equal opportunity (Stanley, 2005). The theory of social integration has been used by different researchers (e.g. Karp, Hughes & O'Gara, 2008; Teoh & Pan, 2008), and international organisations (e.g. the African Union 2008). The United Nations (2009) described social integration as a dynamic process that enables "all people to participate in social, economic, cultural and political life on the basis of equality of rights and dignity" (p. 3). In this definition, social integration is described as a process. In addition, such a process should include all disadvantaged and vulnerable groups and persons (United Nations, 2009). This definition was applied in this study, with particular focus on social and cultural, economic, and political participation. Fielden (2008) suggested three dimensions for local integration namely the legal, social and cultural, and economic dimensions.

A society where there is a lack of social integration can be characterised as displaying the conditions of fragmentation, exclusion and polarisation. These conditions can result in abuse and conflict, neglect and oppression and hostility and combative social relations (United Nations, 2007). As social integration takes place, society displays the characteristics of cohesion, collaboration and coexistence (United Nations, 2007). These three characteristics can be applied in the social and cultural, economic, and political domains respectively (United Nations, 2007). These three domains; socio-cultural, economic, and political reflect the three forms of participation discussed in the following.

3.1 Social and Cultural Participation

The key outcomes of social and cultural participation are feeling safe from threats by other people, toleration, welcome and friendliness, a sense of identity and belonging, feeling an active participant in the community, and having friends (Atfield et al., 2007). Other outcomes of social and cultural participation are the ability to speak the language of the country, and adjusting to the different culture (Ager & Strang, 2008). Interventions in this domain would include active listening and participatory dialogue (United Nations, 2007). From a practical perspective, the interventions imply reduction of social inequality by providing equal access to services (United Nations, 2007).

3.2 Economic Participation

The outcomes of economic participation include equal opportunities for finding employment and work as entrepreneurs, developing business opportunities and participating in the economic welfare of the community (Atfield et al., 2007; United Nations, 2007). Other outcomes include having equal access to benefits, and equal pay (United Nations, 2007). This dimension is important for social integration as it enables the achievement of self-reliance (Atfield et al., 2007). Interventions in this domain would include dialogue between stakeholders such as community meetings and focus groups (United Nations, 2007).

3.3 Political Participation

The outcomes of political participation include attaining legal or citizenship status, entitlements to benefits such as welfare, education or health services, or simply negotiating the legal system or the labour market (Atfield et al., 2007). Other outcomes are the taking of active and complementary roles in governmental and other bodies which can develop the support needed (Atfield et al., 2007; United Nations, 2007). Interventions in this domain would include providing safe spaces enabling the expression of diverse viewpoints and to seek consensus using civic or democratic dialogue, and to participate in political structures and interest groups (United Nations, 2007).

3.4 Justification for Using a Social Integration Framework to Assess the Impact of Mobile Phones on Integration

Social integration is described as a dynamic process (United Nations, 2009). Whilst social networks are an important aspect of this process, there are other factors outside social networks that help and enable integration (Atfield et al., 2007). One of these factors is the use of the mobile phone which has introduced a range of new possibilities, and is thought to impact on society (Kreutzer, 2009). Sinha (2005) argued that the use of mobile phones enabled individuals to strengthen their social and cultural networks, create economic opportunities, and become more politically aware. However, mobile phone usage may also "amplify pre-existing differences in social integration rather than attenuating them" (Puro, 2002, p. 28). Therefore, the social integration framework was considered ideal to the purpose of this study as it provided a wide perspective of analysis of social integration, and is people-centred.

4. RESEARCH METHOD AND PERSPECTIVE

This study has an interpretive perspective, as the research was seeking to obtain interpretations and explanations of the phenomena under study from the respondents. Adopting an interpretive perspective is ideal in understanding the meanings shared through interactions on mobile phones, and how these meanings are assigned to the constructed reality of social integration. Therefore, qualitative methods are well suited to the objectives of this study, as it attempted to understand individual experiences and views.

4.1. Data Collection

This study used ethnographic data collection methods. Data was gathered through interviews and observation of the behaviour and reactions of refugees in South Africa. The fact that one of the researchers is a refugee meant that there was a direct participation in the experience. The researcher tried "to be both insider and outsider, staying on the margins of the group socially and intellectually" (Genzuk, 2003, p. 3). The primary data collection method was semi-structured interviews. Interviews were recorded and transcribed as soon as possible to avoid losing necessary details. Field notes were also taken to gather a variety of information from different perspectives (Myers, 2009). Language issues were among the difficulties encountered. The interviews were conducted in English, which was not the first language of many refugees in South Africa. Many of the quotes have, however, been left unchanged.

4.2 Sample

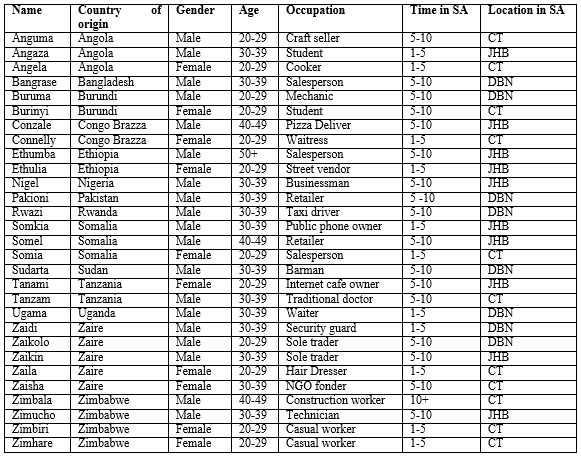

The sample was selected using a purposeful sampling technique by strategically picking respondents who conformed to the selection criteria, such as their country of origin, gender, age, occupation, length of stay in South Africa, and location. The composition of the sample was monitored during the data collection process and the resultant information used to select further respondents. The sample consisted of 29 respondents from the refugees in South Africa. It is appreciated that such a sample is not big enough to generalise, however it allows for achieving the aim of this research which is to identify themes which may in turn be explored in further studies. Similar interesting studies (e.g. Chigona et al., 2009; Friscira, Knoche & Huang, 2012; Kabbar & Crump, 2007) have used a sample of approximate or even less number of respondents and have adopted similar methodology. The sample of this research reflected and took account of the heterogeneity of refugee populations in South Africa, and had representatives of refugees from the major African and other countries. Countries included were Angola, Burundi, Congo Brazzaville, Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Somalia, Sudan, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, Uganda, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and Pakistan (Landau, 2006). The profiles of the respondents that were interviewed and their pseudonyms (based on country of origin) are presented in Table 1.

The numbers of male and female respondents were not balanced. However, there are sufficient females to identify gender issues, if any, relating to the use of mobile phones by refugees. Amongst the respondents, 25 were between 20 and 39 years of age. This reflects the refugee population profile as most refugees in South Africa are in this age group. However, the experiences of teenage refugees who are widely accustomed to mobile phone usage could have enriched the study. The sample was drawn from refugees in Cape Town, Durban, and Johannesburg; three cities in which most of refugees in South Africa reside.

The length of stay in South Africa is important, as it impacts on the respondents' experience of integration. Integration is viewed as a process which changes over time, as the refugees adapt themselves into the host society (United Nations, 2009). Table 1 shows that all of the respondents have been in South Africa for more than one year and more than half for over five years. Occupation reflects the ability of refugees to make use of available work opportunities as part of their integration. The different occupations show how effective the respondents have been in their use of factors such as education, adaptability, aspirations and needs (Atfield et al. 2007). Van Biljon and Kotzé (2008) found evidence that a person's situation such as job status, occupation or income has an influence on mobile phone usage. The relevance and impact of the above elements are considered in the analysis and discussion of the findings.

4.3 Data Analysis

Thematic analysis was used to search for themes or patterns, important to the description of the phenomenon under study. For the analysis of data, this study drew on the six phases of thematic analysis by Braun and Clarke (2006) which are: familiarising with data, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing them, defining and naming them, and producing the report (Braun & Clarke, 2006. p. 87). Initial themes included convenience, social pressure, social and job status, staying in touch, interaction or connectivity, income, cost and time saving, usefulness, care and security. In this study, the coding was informed by the three dimensions of social integration adopted for the context of this study. Based on the collected data, secondary themes were identified and grouped according to the concepts of social integration and the elements influencing mobile phone usage.

5. ANALYSIS OF FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

This section is divided into two subsections, the first covers mobile phone use patterns among refugees, and the second covers the contribution of mobile phone usage to social integration.

5.1. Mobile Phone Use Patterns Among Refugees

No gender patterns were identified in the data. The respondents indicated that the mobile phone services they used included voice calls, SMSs, call-back, and mobile internet. Voice calls and SMSs were the most used services. Whilst illiteracy is a factor in the high use of voice calls in some areas (Friscira, Knoche & Huang, 2012), this was not the case in this study. Although the majority of respondents preferred voice calls, as they are more personal and a better substitute for face-to-face communication, the use of SMS provided the advantage of being at a more reasonable rate, and one SMS can be sent to different persons. This pattern is not uncommon in Africa (Gough, 2005). "Making a voice call is more expensive than SMS but I prefer voice calling … we discuss like face-to-face" (Bangrase).

Five of the respondents used mobile internet. They all indicated that they access social networks, particularly Facebook, and email via their mobile phones. The five respondents mentioned however, that accessing the internet on computers is more convenient than on mobile phones, arguing that mobile phones screens are too small and that the options are limited. "...the problem with mobile internet is that you don't feel satisfy..." (Ugama).

Two respondents shared that they use Mobile Instant messaging particularly MXit. "...MXit is cheap...the problem is that it is not like SMSs that you can send to everybody. With MXit you can chat only with contacts who have been added to the contact list" (Connelly).

These results confirm Biljon & Kotzé's (2008) findings that factors such as cost, connectivity, and perceived usefulness all have an influence on mobile phone usage among refugees. Van Biljon and Kotzé (2008) also suggested that there are cultural and emotional social influences on the use of mobile phones, and this was confirmed in this study. The majority of the respondents stated that 'staying in touch' and convenience was their main reasons for using mobile phones. They also keep their mobile phones as a 'security blanket' and for use in emergencies. As such, Pearce and Rice (2013) argue that in developing countries, resources and social connections are essential to survival.

5.2 The Contribution of Mobile Phone Usage to Social Integration

The findings showed that refugees frequently used mobile phones to communicate with their family members and close friends, but not frequently with acquaintances. It is clear that mobile phones are essential tools for refugees, presenting a vital link between them and their families. The following sections examined the impact of mobile phones on the three forms of social integration discussed previously.

5.2.1 Impact of Mobile Phones on Social and Cultural ParticipationThe findings showed that in South Africa, newly arrived refugees receive little or no orientation to formal networks such as government or semi-government bodies, charities and faith groups from which they can learn about opportunities for housing, work or education. Refugees therefore set up informal networks facilitated by their mobile phones, to share general information on the available opportunities. These informal networks rely on friendship ties often on an ad hoc basis (Atfield, et al. 2007). Mobile phones enabled respondents to get involved in group activities (informal or formal) or voluntary work. For example, the respondents referred to social interactions in both schools and churches. These findings are not consistent with Ager and Strang (2008), who reported that refugees in the UK obtained advice from a number of sources such as Housing Office staff, schools, libraries, and volunteers at drop-in centres. Refugees found this advice important, particularly on arrival (Strang & Ager, 2010).

Both student respondents stated that they used mobile phones to interact with their colleagues and participate in study groups. "...when we have group assignments, we use our mobile phones to communicate between us...to arrange appointments, to exchange ideas or issues" (Angaza). Other interactions included language learning classes, keep-fit classes, pub teams, and sports groups.

Two thirds of the respondents mentioned that they had never participated in formal group activities, or in any voluntary work. The main reason reported was that they were not aware of these groups, they had never been invited to participate or had no time. "...if someone invite me and I have time, I can join...but myself I don't know what is happening around since I work every day from 6 am to 6 pm" (Zaidi).

Lack of trust and language issues were among the reasons respondents gave for not relying more on their neighbours. As a result, refugees tended to turn to co-nationals, and formed networks within them. About one third of respondents hesitated to engage in conversations with neighbours due to lack of confidence in the respondent's language. According to the majority of the respondents, when talking to someone in English, he/she replays it in their home language.

"Sometimes it happen that I need direction in an area…most of the time if I ask someone he answer me in his language that I don't know if it's Zulu or what...this make me confused and uncomfortable... you understand why if one of my friends know the area I call him to lead me…even if he is far?" (Somkia). The findings show that mobile phones may reinforce the homogeneity of the group and impact negatively on their integration into the mainstream community.

The majority of respondents believed that mobile phone communication creates trust between them and their recipients; trust which increases by the frequency of interaction. Some respondents argued that mobile phone numbers are only exchanged between self-chosen friends and acquaintances, to the extent that they do not fear any incoming call even if it's from an unknown source since someone known must have provided it. "I give my phone number only to my friends because I trust them. When I receive a call from an unknown person I don't worry. I suggest he has got my number from my friends" (Somia). However, there is greater trust with those with whom they have formed bonded networks, especially co-nationals with whom they frequently interact.

These findings are in agreement with Dinez et al. (2011), who showed that mobile phones are a valuable resource for social interaction. The findings showed however that, although mobile phones are useful for interaction, problems with language and especially trust hindered some refugees from venturing into relationships outside the group, and mobile phones can thus hinder integration. Mobile phones may also "amplify pre-existing differences in social integration rather than attenuating them" (Puro, 2002, p. 28). The ease of contact between refugee groups and their families in home countries can hamper integration in a host country. However, for refugees, possessing a mobile phone is crucial for social interaction as well as for care and security.

5.2.2. Impact of Mobile Phones on Economic ParticipationMost of the respondents reported that mobile phones helped them to generate income or find employment. Most respondents referred to cost and time saving. Many of the comments referred to the nature of refugee life with its relative lack of permanence in accommodation or work.

Most self-employed respondents agreed that mobile phones helped them earn income; for instance by allowing them to find and retain customers. Others described how mobile phones allowed them to be permanently available to potential customers. Zaila, a hair dresser, noted that with her mobile phone, she does not need to rent a space for a hairdressing salon. Customers call her to get their hair done at home. Buruma, a self-employed mechanic, tells how drivers whose cars have a breakdown can phone him to get assistance. Buruma also uses his mobile phone to shop around and compare prices of car parts without moving out of his workshop. Rwazi, a taxi driver, uses his mobile phone to reduce waiting time, as most of his passengers call him when they need transport. Somel used his mobile phone to supply airtime to casual customers. It is a common practice in much of Africa to receive and relay text messages or to provide cell or fixed line services to those without cell phones and those who cannot read or write (Gough, 2005).

As Gough (2005, p. 1) puts it: "a mobile provides you with a point of contact; it actually enables you to participate in the economic system". Most respondents agreed that, by enabling them to be contactable, mobile phones helped them to find employment. One third of the respondents obtained employment from employers who contacted them on their mobile phones. However, they did not think that mobile phones assisted them in searching for jobs. Some spoke of walking from door to door looking for jobs. Only one used the mobile internet to search for employment, although he was unsuccessful. The majority argued that, although it is possible and convenient to apply online, they were not confident against the competition from South African citizens. "...I don't think one can get a job online while all these citizens are jobless" (Angela).

Whilst there was interest in m-commerce, few respondents could provide the necessary documents to purchase a suitable mobile phone. "I know that with an appropriate mobile phone, like those advertised on TV, one can manage his business and save money...unfortunately great cell phones are only sold on contract...refugees don't have recognised papers [refugees documentation]; no green ID, no bank accounts..." (Conzale) and "...they'll ask you to bring a green ID" (Rwazi). Such statement shows that digital inequality can take many forms including differences in access to type of mobile phone device.

An interest in mobile banking was expressed by several of the refugees. "... I find it [mobile banking] interesting because I can do it at home and save my money for petrol, my time...I prefers stay watch my TV that standing on the queue at the bank" (Nigel).

Whilst Dinez et al. (2011) affirm that mobile banking has become pervasive as a means of financial inclusion, some respondents pointed out that they were unable to use these banking services. "...from the very day a bank clerk told me that refugees are not entitled to all bank services, I became reticent…I believe all innovations in bank services are not for refugees" (Ethumba). Such a statement shows another form that digital inequality can take, that is the differences in opportunities to engage in different mobile phone enabled activities. As such, the benefits offered by mobile banking are limited for refugees in South Africa. Although some South African banks have begun extending services to refugees, refugees are excluded from a number of services such as saving accounts and loans (Landau & Kabwe-Segatti, 2009).

In South Africa, refugees receive documentation that is not recognised by certain authorities and employers (Landau, 2011). Consequently, most refugees in South Africa experience unequal access to the best quality mobile phones devices, and opportunities for engagement in different mobile phone enabled activities such as mobile banking. Most refugees believe that self-employment is their only chance for survival since mobile phones enabled them to earn income, find employment and save costs. However, this study shows that the economic impact is faced with barriers such as documentation and exclusion (Landau, 2008) what can be referred to as being on the wrong side of digital inequality (Pearce & Rice, 2013).

5.2.3 Impact of Mobile Phones on Political ParticipationMobile phones are considered to enable political activity and mobilisation (Kreutzer, 2009). Campbell and Kwak (2009) claimed that mobile phones have added a new dimension to civil society. However, the respondents found little to support these claims. Most of the respondents mentioned that they rarely interacted with authoritative individuals. "I think it is wasting time and airtime trying to raise any issue to the government people, they've got their political program you can't change..." (Zimbala).

However, there was general consensus amongst the respondents that mobile phones, especially using voice calls, are the best medium to interact with authoritative individuals. The main reason cited was that mobile phones enabled a direct link with the person concerned, which is not the case with others media such as letters or emails. "...at least with the cell phone you talk to the person you needed, it's not like a letter which ends unread into a bin" (Tanzam).

This study found that most of the respondents used mobile phones to discuss their rights and obligations, as well as the issues concerning their refugee community. These issues included capacity building, fair treatment and life improvement. One respondent, Burinyi a member of a pressure group stated, "Sometimes refugees experience trouble when registering or when applying for a course...in such case they call us for assistance...we contact the concerned school to solve the issue".

Although respondents recognised the role played by mobile phones in facilitating interaction with authoritative individuals, they did not believe that their concerns have any impact or can influence any government reaction. In certain issues, especially in emergency situations, they reported that they did not receive reliable service. Respondents mentioned that there is sometimes no response or delays in responses when they contact government agents, including police, health care workers and employers. Respondents maintained that the lack or delay in response occurs once authorities recognised their foreign accents. Consequently, in emergency situations refugees mostly use South African citizens to call on their behalf in order to receive reliable service.

"...my friend was stabbed, I called the emergency and the police for help...they came about 40 minutes later, he was dead...my friends condemned me saying I should ask a South African to call for me" (Somkia).

Although there is discrimination, mobile phones can assist in political participation but this is limited. According to Fielden (2008), economic, social, and political participation are the three major domains in which integration policies take place. The overall findings in this section show that, in enabling the development of networks, mobile phones impact on the formation of social capital, a term most commonly used to refer to the nature and impact of social networks which, in turn facilitates integration. Mobile phones also directly enable respondents to participate economically, socially and to a certain extent politically.

6. Conclusion

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of mobile phones on the integration of refugees into South Africa. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 29 refugees in South Africa who spanned a range of selection criteria. This sample was selected taking into account the heterogeneity of the refugee populations in South Africa. The analysis of the data used thematic analysis and grouped the themes according to the concepts of social integration and the elements influencing mobile phone usage.

The study found that mobile phone usage played an important role in the social integration process. Mobile phones contributed to many of the expected outcomes of social and cultural participation. Being in mobile contact with members of their bonding networks helped refugees overcome isolation and feel accepted, safe and confident, but this was not an outcome of integration. Respondents found it difficult to break away from bonding networks due to difficulties with language and lack of trust of outsiders.

The effect of the use of mobile phones on economic participation was strong. Respondents consistently stated that mobile phones were important for generating income and searching for employment. However, these benefits were found to be hindered by barriers such as an inability to obtain the necessary documentation, and exclusion due to language or even accents (Landau, 2008).

Few respondents had anything positive to say about the possibilities of achieving political participation. Most of the respondents used mobile phones to place voice calls to authorities as they believe that only voice contact is likely to receive any response. However, there was scepticism about the possibility of receiving support or understanding from public authorities. It is sobering to think that refugees in South Africa believe that any indication that they are foreign such as their accents can result in poor service.

By using their mobile phones to communicate, refugees can strengthen their cultural and social participation, create economic opportunities, and stimulate their political participation. In South Africa, the context of refugees makes it clear that they are on the wrong side of the digital inequality divide. As result, they do not have the opportunity of engaging in many mobile phone enabled activities, decreasing potential benefits.

Little is done to orient the refugees to organisations that cater for their needs. however, the respondents reported using mobiles to talk to organisations and individuals about issues concerning their refugee community such as fair treatment and life improvement. It is clear that there is discrimination, but mobile phones can assist in political participation but the potential is limited.

The benefits that can be derived from social networks change over time as refugees form new relationships and learn how to get ahead rather than get by (Atfield et al. 2007). Refugee integration is a process which requires mutual adjustment and participation. However, it is clear that the mobile phone can play a major part in social integration.

Integration is a subjective process and the respondents presented their point of view. This may not be the overall experience of refugees in South Africa. The size and composition of the sample may limit the potential to generalise from this study. However, the findings of this study provide scope for further research, perhaps with larger sample sizes or over time. Research could investigate whether without mobile phones refugees would integrate into the host country faster. In addition, the experiences of teenage refugees who are used to mobile phones could be considered in future studies. Research using quantitative methods could be conducted and perhaps with a control group to compare the mobile phone use by refugees and by citizens. The responses could be then compared with the findings of this study. Notwithstanding the limitations of qualitative methods, this study has been able to throw light on the role played by mobile phones in enhancing the integration of refugees into the mainstream community in South Africa.