This paper provides a framework and design guidelines for designing deliberative digital habitats, and relates them to issues of interest in the current development of open data initiatives . It identifies three dimensions that define deliberative digital habitats: the gemeinschaft dimension; the gesellschaft dimension; and the technology dimension; the latter with four different spaces. It will also show the mutual enrichment that online deliberation and open data initiatives can get from each other: on the one hand, the development of open data improves the quality of online participation by making new resources available to support public discussion and deliberation; on the other hand, the availability of web sites designed according to the proposed guidelines would provide the appropriate context for taking advantage of open data as part of the process of democratic engagement. Meanwhile it would help to avoid an outcome where open data initiatives remain — as unfortunately may happen — solely in the technical domain. Finally, access to the datasets collected in online deliberation web sites gives back to the relevant community, and to interested researchers, the civic intelligence resulting from these grassroots conversations.

While not a how-to manual, the proposed conceptual framework, rooted in both existing literature and in more than a decade of e-participation field experimentation, should prove helpful to digital democracy designers, either for public institutions or grassroots movements. As a contribution to the growing body of scholarship on online deliberation, it organizes critical issues so that they will not be overlooked. Examples from field cases illustrate such issues. As well, this paper provides the beginning steps of a methodology for linking on-line deliberation as a means for the effective use of Open Government Data for the enhancement of democratic processes.

Keywords: online deliberation, digital habitat, open data, public policy-making, digital citizenship, digital democracy design, e-democracy, community informatics, Web site design, Facebook

The OECD report on citizen participation (Caddy & Vergez, 2001) identifies access to information as a basic precondition for involving citizens in consultation and decision-making processes. Open government data, (i.e., giving open online access to government datasets), contributes to this requirement, enforcing transparency and enabling citizen participation. E-participation initiatives carried on in the last decade often suffered because of a lack of access to government data: proactive publishing of open data has only recently become a quite well-established government policy. Nevertheless, lessons learned from these early experiences of online deliberation may help designing online environments that take advantage of open data for empowering citizenship in the digital era.

This is the goal of this paper which is rooted in field experiments carried out since 1994 by the Civic Informatics Laboratory at the Università degli Studi di Milano, in cooperation with the RCM Foundation, a non-profit body which grew out from it in 1998 to manage the Milan Community Network (RCM) (De Cindio, 2004).

Since its inception, the Internet has been viewed as a platform for renewing democracy (Blumler & Coleman, 2001; Coleman & Blumler, 2009; De Cindio, 2000; Rheingold, 1991; Schuler, 1994).1 The inventor of the Web, himself, Tim Berners-Lee, recognizes the importance when “designing the future Web” of exploring “how the Web can encourage more human engagement in the political sphere” (Hendler, Shadbolt, Hall, Berners-Lee, & Weitzner, 2008, p. 67). This is both an opportunity and a challenge. Work in the last two decades of the twentieth century and the first decade of the twenty-first, in fields such as human-computer interaction (Dix, Finlay, Abowd, & Beale, 2003; Preece, Rogers, & Sharp, 2002), community networking (Schuler, 1996; Venkatesh, 2003), community informatics (Gurstein, 2000; Keeble & Loader, 2001), e-participation (Macintosh & Tambouris, 2009; Tambouris, Macintosh & Glassey, 2010), and online deliberation (Davies & Gangadharan, 2009; Schuler, 2008), has shown that, despite great effort, advancement towards renewing democracy and extending the role of “citizens as partners” of public institutions (Caddy & Vergez, 2001) has been slow and often controversial. As Wright & Street (2007, p. 864) point out, there is a “stand-off between those who believe that the Internet destroys deliberation, and those who argue that the Internet enhances it.” Cases of unmitigated success are rare, and even cases cited for their positive features present weaknesses [1]. The lack of access to government data supporting informed participation can be one, but not the single, reason for these difficulties.

At a time when human society urgently needs new ways to cope with major problems, and young generations see the Internet as a “platform for change” (Beer, 1975), as recent events in North Africa and the Middle East have shown, we find ourselves at the very early stage of this enterprise (Hendler, Shadbolt, Hall, Berners-Lee, & Weitzner, 2008, p. 65). The capital that computer scientists can and should bring to the challenge of renewing and extending democracy is not mere technology: rather, it lies deep in the roots of the discipline, as outlined by Nygaard (1986). It requires conceiving of informatics (the term Nygaard suggested using instead of “computer science”) as an empirical discipline whose phenomenology is the impact of computing technologies on society.

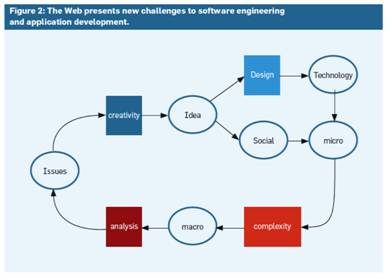

Being empirical implies that “successful models evolve through trial, use, and refinement.” (Hendler, Shadbolt, Hall, Berners-Lee, & Weitzner, 2008, p.67). But, if feedback from trials is to be beneficial, the trials must be conducted in real-life settings, a requirement illustrated in Hendler, Shadbolt, Hall, Berners-Lee, & Weitzner (2008, p.62) by scaling up from micro to macro. This is to say that it is not sufficient to perform tests “in vitro”, with a limited number of participants or with a “special” population, as often happens. Furthermore, trials must be consciously designed according to a conceptual model so that their actual outcome can be assessed and compared to an expected outcome. Only in this way can the underlying model be confirmed or refuted, or, as usually happens, adjusted. This perspective raises software applications running in real-life settings to the rank of field experiments testing the conceptual model behind the design.

Design is actually a key aspect of informatics, but the ease of use of current Web-based technologies often leads to underestimating its importance. It is all too easy for designers, let alone practitioners, to be seduced by mashup techniques (i.e., the ability to merge existing data and reuse applications) that give the illusion of quickly creating an interactive social environment. Websites set up to establish some form of dialogue between a public institution and citizens may have an accurate and attractive graphic interface, and include a ‘collage’ of popular net applications: a discussion forum, a blog area, maybe a wiki and some social-networking features, placed side by side, in the vague hope that this will somehow attract citizens and engage them in public dialogue. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Wright & Street (2007, p.864) have shown that, even in the case of a simple discussion forum, design choices (e.g. adopting a prior moderation policy) or software features (e.g. a threaded message system that encourages replies) influence whether the software “impedes” deliberation or “facilitates” deliberation. Software features and design choices are what shapes the social environment. This is not surprising. In his influential book, Bringing Design to Software, Winograd (1996, p. xvii) states: “Software is not just a device with which the user interacts; it is also the generator of a space in which the user lives.” He also claims: “Software design is like architecture: When an architect designs a home or an office building [...] the pattern of life for its inhabitants are being shaped. People are thought of as inhabitants rather than as users of buildings [...] focusing on how they live in the spaces the designers create.”

This paper aims to draw attention to the design of online spaces where both civil society and those public institutions that actually want to involve citizens engage in effective, online, deliberative processes whose purpose is to augment offline participation with a Web-based environment. Therefore, our subject is the design both of government-run deliberative sites and of online spaces promoted by civil society organizations with civic purposes. The notion of a deliberative digital habitat helps us characterize the scope of the work and then frame a set of issues worth considering when designing a digital habitat that enhances deliberation.

In keeping with the empirical nature of informatics noted above, this paper has a strong empirical basis, being rooted, as previously mentioned, in the field experiments carried out since 1994 by the Civic Informatics Laboratory at the Università degli Studi di Milano. All these field experiments have been analyzed to collect feedback and presented to the scientific community to improve the approach. We thus began to draw up the framework presented here, which is mainly rooted in the fundamental literature on virtual communities (Rheingold, 1993), community networking (Schuler, 1996; Venkatesh, 2003), online communities (Preece, 2000), technology for communities (Wenger, White, Smith, & Rowe, 2005), and online deliberation (Davies & Gangadharan, 2009; Schuler, 2008).

To illustrate design issues with actual cases, the following are referred to repeatedly:

FixMyStreet in the United Kingdom, the Internet Reporting Information System (IRIS) in Venice, and Sicurezza Stradale, or “Road Safety,” in Milan allow citizens to use a map to report problems for local government to fix. (These sites are to be found at http://www.fixmystreet.org, http://iris.comune.venezia.it, and http://www.sicurezzastradale.partecipami.it.).

partecipaMi is the umbrella under which Sicurezza Stradale takes place: it represents the evolution of a Web site — ComunaliMilano2006 — that was set up to foster dialogue between candidates and electors on the occasion of Milan’s 2006 municipal elections (De Cindio, Di Loreto, & Peraboni, 2008). partecipaMi was renewed for the spring 2011 municipal elections (De Cindio, Krzątała-Jaworska, & Sonnante, 2011) and is now increasingly taking on the role of a significant online public square for the city.

e21 for the Development of Digital Citizenship in Agenda 21 project is aimed at supporting the well-known Local Agenda 21 participatory process with a suite of integrated software tools. It was funded within the “Call for Selecting Projects to Promote Digital Citizenship (e-Democracy)” issued in 2004 by Italy’s Ministry for Technology and Innovation, and involved ten different municipalities in Italy’s Lombardy Region. Its results were presented in De Cindio & Peraboni, 2009.

The Popolo Viola (literally, “purple people”) movement (Mello, 2010), which sprang up, completely online in 2010 on a Facebook page, to organize a demonstration asking Prime Minister Berlusconi to resign.

In addition to these cases cited repeatedly, other examples are introduced and presented when called for. Most of the design issues are well known and discussed in the literature. However, we believe our work makes a new contribution by identifying a framework for understanding the relevance of the issues. Some empirical evidence that the framework fulfills its promise will be sketched out in the conclusion.

In recent years, participatory or deliberative initiatives launched by public institutions and grassroots movements have often been promoted with the “Web 2.0” label to suggest active citizen involvement and participation. However, most such initiatives actually only support sharing information and/or gathering it, as explained in De Cindio & Peraboni (2011). Only in a few cases do governments use ‘Web 2.0’ to hear citizens’ opinions on policy issues or involve citizens in the decision-making process. The PeerToPatent.org initiative is one of the few cases in which citizens have an actual impact on the decision-making process, since the information citizens provide influences the decision outcome (Noveck, 2006).

The online participation environments to support peer-to-peer communication, participation, and deliberation that we wish to design are complex “spaces for human communication and interaction” (Winograd, 1997, p.156) and require a “better understanding of the features and functions of the social aspects of the systems” (Hendler, Shadbolt, Hall, Berners-Lee, & Weitzner, 2008, p. 66), coupled with the technical knowledge needed to develop simple, straightforward solutions. Following Wenger, White, & Smith (2009), we term these online environments digital habitats, i.e. habitats in the ecological sense that have been created and mediated by digital artifacts.

It is useful to apply the expertise and knowledge accumulated during studies of early online social interaction environments to the analysis of modern digital habitats. Virtual communities (Rheingold, 1993), online communities (Preece, 2000) and Web communities (Kim, 2000), as well as communities of practice (Wenger, McDermott, & Snyder, 2002) and civic and community networks (Schuler, 1996; Venkatesh, 2003) have been studied extensively. Preece (2000) and Wenger, McDermott & Snyder (2002), with minor differences, both define these early online environments as a set of people who: (a) freely interact over time and recognize a common interest that bonds them together through shared knowledge, experience, practice, history, ritual, and so forth; (b) define implicit or explicit policies to regulate their interaction; (c) use a system based on information and communication technology.

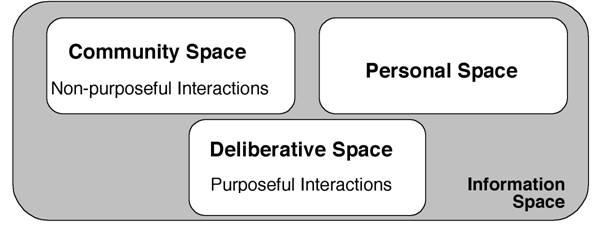

Following Rheingold (1993), who applied the term “community” to early examples of online aggregation, in De Cindio, Gentile, Grew, & Redolfi (2003) we adopted sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies’ (1887) distinction between community, Gemeinschaft, and society, Gesellschaft. Online spaces are defined both by voluntary interaction among people who thus build a shared culture, the gemeinschaft dimension and by the body of rules that govern online life, the gesellschaft dimension, analogous to the normative features of a well organized society (De Cindio, Gentile, Grew, & Redolfi, 2003). The first dimension is determined by the members of the community. The second dimension is determined by the social pact that binds them together. A third dimension is a function of the technology on which the environment is built. The social environment of the digital habitat is shaped by its gemeinschaft and gesellschaft dimensions, the physical environment by the technology dimension.

In terming these independent but interrelated factors “dimensions,” we are grounding the metaphor is physical space, i.e. the habitat conceived of as volume in a metaphorically Cartesian sense. Applying a different metaphor might be another useful way to look at the problem. We could follow Giddens (1999, p. 78 rev. ed.) who states: “A well-functioning democracy has been aptly compared to a three-legged stool. Government, the economy and civil society need to be in balance.” Changing the vehicle of our metaphor, we conceive of the digital habitat as a platform and thus might say that gemeinschaft, gesellschaft, and technology are the three legs to consider during design for a well-balanced environment. The three-dimensional digital habitat, on the other hand, allows for greater extension of any of its dimensions into space beyond, including, critically, deliberation or interaction that takes place outside the specific volume of the digital habitat but is connected to it along one or more of these dimensions. A meeting or referendum held offline may indeed be part of the gemeinschaft or gesellschaft dimension, even though not within the habitat per se.

The design process for a digital habitat (be it an online community, a social network or a deliberative Web site) thus ought also to unfold along these three different dimensions. Such an approach can be seen as an extension of Preece’s claim that “designing for usability is not enough; we need to understand how technology can support social interaction and design for sociability” (2001, p. 349). The design of technology includes, but is not limited to, usability considerations. Sociability, in and of itself, has these two interrelated but somehow independent design dimensions. And sociability relates to what Wright & Street (2007, pp. 857-859) have found in showing that a given technology – namely, a discussion forum – may produce different effects upon dialogue depending on the policies (the rules shaping online conversations) adopted to manage it. Actually, we suggest that it is useful to work the other way around: first designing the desired social contract (the gemeinschaft and gesellschaft dimensions) and then choosing the technology that best enables and supports it.

Although our proposed framework has also been successfully applied in non-civic contexts (like restyling the Italian Basketball Federation’s Web site to include an interactive space), this paper focuses on designing deliberative digital habitats, online spaces used for civic purposes, where citizens and public officials engage in public dialogue about public affairs, hopefully achieving a decision. Abstracting from our field experience and from established literature, we identify here a set of issues to consider when designing the three above dimensions. These issues are phrased as a set of questions below.

Examples discussed by Wright and Street (2007, p. 858) show how these issues may be overlooked when a public institution promotes a site for involving citizens in a participatory or deliberative process. Cases cited elsewhere in the literature, including chapters in Davies & Gangadharan (2009), provide confirmation. Citizens themselves may also neglect such issues when they open an online venue: “We want to discuss the election of the new university rector” or “We must protest the ad personam laws that Prime Minister Berlusconi wants to enact.” The immediate response, in both cases, was: “Let’s open a group on Facebook,” and that was it, as far as the design effort went. The first case achieved total failure. The second, Popolo Viola, was a great success, initially, but has since run into serious problems precisely because of the lack of design in gesellschaft and in technology.

“We need to study the processes by which Web sites are commissioned and the parameters that are designed into the software,” (Wright & Street, 2007, p.859) state. The following paragraphs attempt to contribute to that effort ex ante, i.e., by providing a framework for discussing design choices. Like Wright & Street, we feel that: “a fully-fledged analysis falls beyond the scope of this article.” However, we hope to add some plumage to help the fledgling along. Examples from field cases show how design of the three dimensions can be addressed well, as well as how easy it is to overlook design.

It is widely recognized among those who work on social interaction environments that there is no recipe for triggering participation and keeping it alive. The spark that fires participation is largely unpredictable. Wenger, McDermott, & Snyder (2002) aver that (online) communities (of practice) need to be cultivated: the gardener prepares the ground, chooses and sows the seeds, waters and fertilize the plot, checks that seedlings sprout, and fosters growth by cutting dead branches. Yet, in the digital – as in the physical – world, several accidental, hidden, even unknown factors may heavily influence the yield. Hendler, Shadbolt, Hall, Berners-Lee, & Weitzner (2008, p. 66) note that a purely ‘technological’ explanation cannot account for the success of Wikipedia built on top of the MediaWiki software versus the failures of many other sites using the same software. “Similarly, the protocols used by social networking sites like MySpace and Facebook have much in common, but the success or failure of the sites hinge on the rules, policies, and user communities they support.”

In this context, it might appear ambitious to propose guidelines for designing the community-participation experience that characterizes a social environment, because this would require identifying ways to enable community to be created. However, empirically learned lessons are worth sharing. Inspired by Caravita’s (2002) analysis of success factors for commercial Web sites like Amazon and eBay, reflections are offered here on the reasons that motivate various social actors (citizens, stakeholders, public officials, politicians) to interact and participate in the online public arena. Such participation can be seen as a win-win game. Especially in public political settings, various individual participants and more or less organized groups may have quite different goals. It is important to identify, for each kind of participant, the motivations that lead to participating. Creating a substrate online environment of sharing and mutual trust is a sine qua non for deliberation.

This task of identifying a “social glue” is easier in the case of grassroots movements because they usually arise and mature around a shared issue. It can be harder in the case of top-down, government-run deliberative digital habitats, where topics to be dealt with are usually (already) defined. Comparative analysis of the ten government-run e-participation field experiments in the e21 Project (De Cindio & Peraboni, 2009, p. 119) showed that previous online community experience was certainly a positive factor, indicating the importance of a properly designed gemeinschaft dimension.

The first issue to consider is how to establish who has to be involved in the online initiative. In an augmented social environment, where technology breaks down time and space barriers, this choice becomes even more influential and affects the notion of citizenship in a certain way.

Different categories of citizens are traditionally distinguished when the deliberative platform refers to a geographic reality: permanent residents, who spend their lives there, temporary residents, such as students, who dwell in it, and commuters, who come in daily to work or study. Whereas only residents are eligible voters in local elections, people in the other categories may also be significant social actors in a deliberative initiative promoted by a public institution. Actually, this decision has to be made for each phase or activity in the participatory process. While temporary residents and commuters might be allowed to participate in public forums — both the offline meetings and their online extension — perhaps only residents would be considered eligible voters in a more cogent decision-making activity, such as a citizen consultation with a binding outcome.

For example, both FixMyStreet in the UK and IRIS in Venice, Italy, allow anyone to use a map to report problems for local government to fix. Similarly, Vigevano, one of the ten municipalities in the e21 project in Italy’s Lombardy Region, allowed anyone to join discussions among civil servants, elected officials, and the citizenry on the e-participation Web site it set up as part of the project (http://e21.comune.vigevano.pv.it, no longer online). However, when drawing up new regulations for equal opportunity in municipal government, Vigevano allowed only the civil servants actually affected by the decision to participate in the deliberation process.

Not surprisingly, this issue is also significant for grassroots movements, which have to decide who can participate in their online environments: the citizens of a territory, only movement members, anyone registered on a platform (e.g. Facebook) or those who meet some other criterion. For example, on the 40xVenezia Web site, which belongs to a movement promoting innovation in Venice, only city residents could participate at the outset. Now, however, anyone can register on the site but must explicitly declare how s/he is involved with the Venice area and be accepted by the Web site administrators. Moreover, the movement restricts some of its (online) activities, such as voting on ideas, to official members of the 40xVenezia association.

When defining the gemeinschaft dimension, above, we posited a shared interest that holds people together but avoided assuming a shared goal. We have discussed this issue before (De Cindio & Ripamonti, 2010) and believe it has major consequences for the design of effective deliberative digital habitats. A rather common assumption is that the social actors who engage in a participatory or deliberative process do this because they have a shared goal. In fact, the actual goals may differ for each participant. Yet, though their ultimate goals might differ significantly, all the social actors may be interested in sharing knowledge and opinions on a given issue. The promoters and designers of the deliberative digital habitat need to ask themselves: “What stake have the various actors we want to engage in public discourse got in participating?”

This is what we mean when we say that the participation experience should be conceived of as a win-win game that motivates the various social actors to participate in the online public arena. This requires identifying a set of activities (both online and offline) that trigger the social actors’ participation. Of course, the reward is not necessarily (if ever) monetary. A citizen who takes the time to report — through a Web site provided by (or in collaboration with) city government, like FixMyStreet, IRIS, and Sicurezza Stradale — a problem, a hazard or something broken, reasonably assumes it will be fixed, or at least noted, in a reasonable amount of time, and awaits news. In this case, the reward consists of contributing to the quality of one’s habitat. Of course, if nothing happens, the citizen gets frustrated and is unlikely to make another report.

The IRIS initiative is an example of an effective win-win game. Citizens report problems, which are handled directly by Venice city government. The IRIS system lets citizens keep track of reported problems by making the procedure visible. The Web site displays the report’s date, its reference number, the office it was assigned to, its status (“received,” “assigned,” “solved” or “closed”) and messages from that office explaining its current status (e.g., why a problem was closed, unsolved).

When a public institution calls citizens to a more complex participatory process, such as participatory budgeting or a local Agenda 21, participants are asked to devote more time and expect correspondingly greater reward for their engagement. If unforeseen events delay the process, the hindrances need to be prominently published. For example, in the case of the e21 project, most of the deliberative initiatives failed for political reasons, such as the alderman in charge of the participatory process being replaced or the governing coalition that had promoted the initiative falling. In none of these municipalities did government explain the situation. Citizen participation consequently abated (De Cindio & Peraboni, 2009).

If a new digital habitat is to actively engage people, its planning needs to include strategy for consolidating — or, if need be, creating — a common identity for participants to recognize themselves as a community. The goal is to create interest and curiosity about the initiative and, at the same time, to foster the growing sense of community. In establishing common identity, helpful factors include an effective slogan, a logo or brand, a shared history, and a common present (Kim, 2000).

The creation of a common identity is particularly critical for grassroots movements, which need to aggregate various people around a shared cause. Such design of a common identity is epitomized by the case of the Popolo Viola. From the outset, this movement characterized its online identity with: (a) a simple, strong message, summarized by an effective slogan: “No B. Day”; (b) a color, identity-making purple, chosen in lively discussion on Facebook (Mello, 2010, p. 161); (c) a shared logo, proposed by a graphic designer participating in the discussion (Mello, 2010, p. 166).

Creating common identity may also factor into the success of public sector initiatives, especially in coping with citizens’ growing disaffection with government and for elected officials (Coleman, 2005). An example of such success comes from Italy’s Apulia Region, Puglia, an administrative division with some four million people in six provinces, which decided to create a public ‘brand’ as part of policy measures aimed at young people. The regional government named the initiative Bollenti Spiriti (or “Boiling-hot Spirits”) and used this brand to create a community of young people (at http://bollentispiriti.regione.puglia.it) and involve them in the initiative (Scardigno, F. et al., 2010). The site’s popularity was a major factor in the measures’ success.

When designing the participation experience, it is also important to take into account that participation, rather than a continuum, is a discrete phenomenon characterized by peak moments when the actors are more inclined to participate (De Cindio, Di Loreto, & Peraboni, 2008). The peaks may be due to specific situations such as election campaigns, protests against an ongoing or upcoming policy or mere dissent. Dissent may arise even over some minor decision that affects people’s territory and lives, such as inverting the direction of a one-way street or opening a new decentralization office (two real-life examples from Sicurezza Stradale and partecipaMi, respectively). When shaping the win-win game, designers should be well aware of this. It would be risky to assume that hard-won citizen participation will continue to increase. Because this is not the case, the win-win game needs to be designed flexibly enough to seize the opportunities offered by these hot moments and then consolidate peak participation into a more ongoing practice.

In order to set up an effective deliberative digital habitat, the win-win game, once identified, needs to be formalized in a ‘participation contract’ that binds the parties: the initiative’s promoters, its participants, and the government agencies involved. The participation contract also defines the interplay between online and offline participation, outlining online impact on the ‘real’ world [2].

The participation contract of many ‘Web 2.0’ initiatives is often not as clear as one might wish. FixMyStreet, promoted by the independent body MySociety, is a very successful initiative. But even here, UK town councils’ commitment vis-à-vis citizens’ reports on the Web site remains vague. Nor is it prominently displayed online. For a long time, only in the FixMyStreet.org FAQ section might one discover that: “[The problems] are reported to the relevant council by email. The council can then resolve the problem the way they normally would.” A recent improvement has made interaction among the parties clearer, but this information can now be found only indirectly through a link to MySociety.org.

The situation worsens when the initiative (such as MyBikeLane.com or Caugthya.org) is independently promoted by (groups of) citizens with no connection to a public institution. In these cases not only is the relation with government unclear but the commitment between promoters and participants is also left unspecified.

When the initiative is directly promoted and managed by a government organization — as, for example, in the cases of the IRIS system run by the City of Venice and of PeerToPatent.org run by the U.S. Patent Office — it is the organization’s job to define and publicize the commitment made to those who participate. Public institutions should never make promises that they cannot fulfill: in our experience, citizens agree to engage even if the actual participation boundary is quite limited, but they are firm in demanding that the participatory contract be observed. Public organizations, on the other hand, are often inclined to promise more than they can, or actually want to deliver, and it is difficult to convince them that this may be a sort of boomerang.

According to the theory of the communication disciplines proposed by C.A. Petri (1977), identification regards the attribution of an identity to the source of a message with different levels of accuracy. This process “involves demonstrating the identity of the source [..] of phenomena down to the mere technical details” (Petri, 1977, p. 175) and includes (but is not limited to) users’ authentication on a Web server. Authentication concerns the technical aspects of identification and refers in particular to accounts, roles, permissions, and the like. The identity of the sender is part of the significance of a message.

Authentication and identification policies are crucial for an effective habitat, and are closely linked to the selection of social actors discussed above. To facilitate participation and avoid entry barriers at registration time, several Web 2.0 participation initiatives analyzed in De Cindio & Peraboni (2011) adopt a weak authentication policy. Often no registration is required and, even when mandatory, participants have to provide only a nickname and maybe an email address, which is actually checked in only a few cases. Because of this choice, posts are signed by a virtual identity, which makes them de facto anonymous. Anonymity is a right that must be protected in contexts where freedom of speech is restricted by non democratic regimes (Clinton, 2011). Naturally, it “free[s] interaction participants from potentially feeling socially inferior to their counterparts and, thus, facilitate[s] expression of everyone” (Rhee & Kim, 2009) and indeed may be acceptable in some contexts, e.g., when rating a movie on the Internet Movie Data Base. However, anonymity does not foster the rise of mutual trust that online environments set up for deliberative purposes need to inspire. Public dialogue on significant civic issues with a group of digital ghosts is neither gratifying nor stimulating.

In this regard, it is worth recalling the case of San Precario (where san means “Saint” and precario translates as “temporary employee”), the anonymous identity who founded, owned, and managed Popolo Viola’s Facebook ‘page’ for quite some time. According to Mello (2010), San Precario is a virtual identity created in 2004 at a meeting of underground groups in Trento to promote a demonstration to be held on International Worker’s Day as an alternative to the traditional trade union demonstration. Initially the page administrator’s choice to remain anonymous fostered the idea of a collectively led movement (Mello, 2010), but its critical nature became clear when San Precario, “Saint Temp,” banned several participants who had argued against his proposals and, even worse, removed other administrators’ administrative privileges and banned some of them (Caravita, 2010). Finally, on Sunday, August 22, 2010, San Precario decided to resign as administrator of the page, leaving it “to three of the people who have most contributed to its growth.”

Our long community-network experience suggests that this weak form of identification is inadequate, if a trustworthy social environment that encourages public dialogue and deliberation is to be created. Online identity should, insofar as possible, reflect offline identity: if citizens wish to get a public answer from someone who plays a public role and appears online with her/his actual identity, they must do the same. They have to ‘show their face’ and take responsibility for participating under their actual identity (Casapulla, De Cindio, Gentile, & Sonnante, 1998). This serves also to root the online community in the “proximate community” served by the network (Carroll & Rosson 2003).

Nevertheless, even in online deliberative contexts, there are cases in which it is worth protecting participants’ privacy. This might occur during public consultations and discussion on sensitive issues or public assessments of an official that could bounce back on the participants, as in the case of the assessment of a teacher by his/her students as well as in the case of doctors rated by patients (e.g. http://www.patientopinion.org.uk/). In all these cases, there is the need to integrate a strong authentication policy (so that, e.g., only the students who have actually taken a class can rate the teacher) with secrecy techniques for protecting participants’ identity. Software can help achieve this by obscuring the identity of the sender of a message in such critical discussion areas.

The recommendation to use actual identities online does not mean adopting a rigid and strict authentication and identification policy. It should be flexible and appropriate for each participation level: weaker levels of involvement require weaker responsibility, higher ones, higher. So, for instance, unverified identities are enough for writing a comment in a blog, whereas strong authentication is required for participating in a deliberative consultation.

For public dialogue to be purposeful activity, as a deliberative civic habitat requires, conversations must have certain distinguishing features: interactivity (Winkler, 2007, p. 188), rationality (Fishkin & Luskin, 2005, p.40; Winkler, 2007, p. 188), and a chance for each participant to feel at ease and have equal opportunity to express ideas, in a climate of nondomination by a “minority of frequent posters” (Coleman & Blumler, 2009, p.100). We return to these features below in considering how technological choices foster them. However, technology in itself does not suffice, especially in sensitive or conflictual habitats. Rules are needed to prevent flames, limit trolling, and harmonize “the tension that exists between individual and community rights” (Schuler, 1994). Only through such harmonization can a positive climate characterized by mutual trust among participants be created, as has been widely recognized (see, e.g., Edwards, 2002; Schuler, 1994; and Wright, 2009).

Inspired by early free nets, community networks, and civic nets (Schuler, 1993) and wary of the difficulties that public initiatives such as Santa Monica PEN (Public Electronic Network) had encountered (Docter & Dutton, 1998), all the online civic sites we manage have, from the very beginning (Casapulla, De Cindio, & Gentile, 1995), adopted a guide to participants’ behavior we term Galateo. This term, inspired by Benevento archbishop Giovanni Della Casa’s famous treatise on manners (Della Casa, 1558), also aimed to translate the then-neologistic English term “netiquette.” More recently, terms like “code of conduct,” “rules of engagement,” and “terms-of-service agreement” have gained currency with reference to documents very much like what our Galateo has evolved into. We have kept the term Galateo to stress that its purpose is to define a set of standards and specific rules for online behavior that, above and beyond common netiquette, on the one hand, and (Italian) law, on the other, should guarantee fair dialogue in a welcoming environment, where everyone can feel at ease expressing her/his own ideas and opinions (De Cindio, Gentile, Grew, & Redolfi, 2003). The Galateo has to be precisely written, published in highly visible fashion within the online environment, and signed by participants when they register and create their accounts. Thus, every participant is acquainted with it and nobody can protest in case of disciplinary sanctions due to repeated violations.

While a well-defined Galateo helps avoid long follow-ups to unpopular decisions, it needs to include rules affecting the behavior not only of generic participants but also of those in special positions: moderators, community managers, officials, and technical staff. Negotiation about these rules and roles should be possible (Edwards, 2002, p. 18) but such negotiation, unchanneled, risks triggering a complex, tiring, never-ending process, which can ultimately weaken mutual trust, as our experience, partly described in De Cindio, Gentile, Grew, & Redolfi (2003), shows.

The participation contract, the identification policy, and the Galateo are the three official statements that define the mutual commitments among a digital habitat’s social actors and shape its social structure. This principle implies the need for there to be a trusted person (or group) committed to having these agreements respected. This raises the issue of moderation.

The role of moderator has been widely discussed (Kim, 2000; Preece, 2000; Rheingold, 1993; Schuler, 1994). In forums on public issues, the role played by moderators is especially significant because it affects the basic principles of democratic discourse (see, e.g., Edwards, 2002; Wright, 2009; and Wright & Street, 2007). This holds true both for discussions initiated and managed by a government organization and for grassroots initiatives by generic citizens. In both cases, the main, though not sole, issue is to guarantee that the declared participation contract binding the social actors be observed. It is this guarantee that calls for a trusted person to make sure the Galateo is honored. Trust comes from personal disposition and reputation, as well as from institutional role. We discuss the trusted person’s community relations here and her/his institutional role thereafter.

If the ultimate role of a moderator is to make sure the participation contract is adhered to, s/he needs to be authoritative enough to act “as an ‘arbiter’ [who] may designate certain postings as inappropriate and decide to remove them” (Edwards, 2002, p. 4). In order to do this without being considered a censor who removes postings that fail to comply with the Galateo or a policeman who bans participants, s/he has to gain people’s trust so her/his work is seen as a service to the community. The way for the moderator to acquire this reputation is to help participants state their ideas in fair, civil fashion, acting as a digital communication expert who helps less-skilled participants (public officials, politicians, and elected representatives, as well as members of the public) cope with the dynamics typical of online environments. This is to say that the roles of discussion facilitator, host, discussion leader, and online helper, discussed by Edwards (2002) while surveying the vast literature, are ultimately ancillary to acquiring the reputation needed to act as referee when circumstances warrant. However, moderators spend most of their time performing these ancillary functions, in the hope they will be never need to use their authority. For this reason, we prefer to speak of community managers rather than moderators.

Facilitating more inclusive participation is another task among these ancillary functions and is important in public environments where politicians as well as generic citizens may lack the skill necessary to participate. The community manager prods unregistered participants who often contribute to register, so they can play a greater role and access higher levels of participation. Similarly, in order to increase participants’ visibility as community members, the community manager should also encourage registered users to complete their profiles.

Defining the Galateo and identifying one or more community managers to oversee ongoing activities is therefore a truly crucial and very tricky issue. When the deliberative habitat is run by government, this also involves the moderator’s independence, as discussed in the following subsection. For non-institutional, grassroots initiatives, the main problem is that a fully volunteer community manager is unlikely to be able to assure the needed continuity. In both cases, sharing the community-manager role among more than one person may prove even more complex, as the experience discussed in De Cindio, Gentile, Grew, & Redolfi (2003) and the experience of Popolo Viola described below show.

The way Popolo Viola originally managed its Facebook page is an effective example of collaborative community management. A group of the page’s most active supporters “monitored the discussion on the wall, when necessary intervening with posts [to steer discussion away from digressions] and, in the most serious cases, reported problems to the administrators, who could remove the message and/or ban the poster. Administrators could act independently” (Renzi, 2010). It is important to note how strongly the digital environment chosen for the initiative, Facebook, determined what moderation actions were available to page administrators (removing comments or banning people). Policies for removing posts or comments and for banning people were not explicitly stated on the page. However, the praxis evolved to consist of removing messages or banning people because of two kinds of problems (Renzi, 2010): (a) style problems: hot tone, angry words; (b) Popolo Viola image problems, which arose when someone complained about a promoter’s behavior, often San Precario’s.

These moderation choices began to show their limits just few weeks after the successful demonstration when (in February 2010), following disagreements among administrators on specific movement decisions and with no clear rules, the anonymous San Precario, decided to ban all the other administrators from the page (Caravita, 2010). This set in motion a never-ending crisis that led the Popolo Viola to disappear from the political arena in the space of about a year.

Whereas in grassroots initiatives the moderator or community manager is usually a participant who plays this role as primus inter pares, when the deliberative habitat is promoted and run by a government institution, the moderator’s independence becomes an issue (Edwards, 2002, p. 17). Who does s/he ultimately answer to? To the government organization or to the citizenry? This is closely related to another issue: while the moderator has to guarantee that all participants respect the Galateo, there is also a need to ensure that the participatory contract itself is honored. These issues raise the question of a possible role for a third-party ‘guarantor’ of the deliberative environment.

Furthermore, even if the participatory contract is well defined, directly managing an online environment is not necessarily the easier solution for a government institution. It may be critical, for instance, to host a discussion in which citizens strongly criticize the administration or some of its key figures. This happened in the 1990s on the Rete Civica di Roma (Rome Civic Network), which was hosted on City of Rome servers. Moreover, if the public institution does not fulfill the participation contract, citizens have no one to turn to for help. A trusted third party, acting as an intermediary between government and citizenry, might help avoid such problems.

The need for new bodies to play this role has been recognized from different perspectives: Blumler & Coleman (2001) call for “an entirely new kind of public agency, designed to forge fresh links between communication and politics and to connect the voice of the people more meaningfully to the daily activities of democratic institutions.” Bellezza & Florian (1998) identify the need for new, third millennium bodies to lend stability to various cultural initiatives. We created just such a new body in 1998 to oversee the Milan Community Network (“RCM” by its Italian acronym). The RCM Participatory Foundation brings together – in different roles – local government institutions, the university, private enterprise, and exponents of civil society, i.e. individuals, nonprofit associations, and schools (a structure fully documented in De Cindio, 2004). MySociety, set up in 2003, is another relevant example of such new bodies.

For the purposes of this paper, it is worth understanding these new agencies’ roles within the similar online initiatives they promote, FixMyStreet.com and Sicurezza Stradale, where their fundamental roles are:

Regarding this last issue, it is worth noting that right now, when public conversations take place through “free” online spaces managed by private businesses, such as Facebook, under a policy which gives them the ownership of all the data, not only personal data provided at authentication time but also all the civic intelligence resulting from people conversations become the private property of the corporate host. While there is an increasing public concern about the ownership of personal data, this loss of public wealth due to the alienation of this form of civic intelligence has gotten much less attention.

One post by a Milan City Council member in the “Citizenship and Democracy” forum (http://www.partecipami.it/?q=node/7903) of partecipaMi aptly illustrates how significant the role played by a trusted third party can be:

The discussion started by Claudio Edossi about the Ecopass [traffic access] policy, which has involved several city council members, both from the majority and from the opposition coalitions, highlights the growing importance of the role played by partecipaMi (and by the RCM Foundation): it represents a ‘no-parties land,’ a place where councilors feel free to take part in a political discussion, while thinking of the city’s actual interests, regardless of their membership in a given political party or of the balance of power between political parties. [...] This situation might appear paradoxical, but it ought to sound a political alarm. The results and the impact of the Ecopass policy — which is the only new structural measure to reduce traffic and pollution in a major Italian metropolitan area — are being discussed neither in city government meetings nor in city council meetings: council members and city managers discuss it on partecipaMi! (bold in original)

It is worth noting the importance of the nonprofit nature of the third parties involved as guarantors and how risky it might be to assign such a role to a business-oriented company. An example of the problem with private interests in this context can be seen in the case of Beppe Grillo’s blog. Grillo is a well-known Italian comedian-turned-political-activist. His blog is by far the most-visited blog in Italy, and a political movement, Movimento Cinque Stelle arose from it. In Italy’s spring 2011 municipal elections, members of Cinque Stelle were elected in several cities. This shows that Beppe Grillo is playing an increasingly significant role in the Italian political arena. However, his blog is fully managed by a private company, Casaleggio Associati, whose mission is to develop strategy for its clients’ Web presence. The company offers a centralized management model. It decides strategies and rules by applying extensive control over several Web 2.0 environments. When applied to Grillo’s blog, this model mixes the company’s strategy (driven by marketing and business issues) and the movement’s political strategy, casting doubt on its use in the political arena (Orsatti, 2010). These misgivings found confirmation in the recent decision made by another political party, Italia dei Valori, to cease relying on Casaleggio Associati to manage its online presence.

As noted, current practice for setting up a deliberative Web site too often comes down to the choice of a few tools (a forum, a blog, a calendar, etc.). The implications of technological choices are not always well thought out. In recent years, for instance, the rush to set up such sites has tended to include opening a page or group on Facebook and a channel on Twitter. Although technology is not always the key success factor, it can nevertheless play a significant role in shaping participation. As early experiences with online communities have taught, “good technology in itself will not a community make, but bad technology can sure make community life difficult enough to ruin it” (Wenger, White, Smith, & Rowe, 2005, p.9). Technology should, insofar as possible, support the social game and the social structure that has been designed.

Because of the increasing popularity of Facebook among politicians, it is worth briefly discussing the impact of some of its technical features (as they stand at this writing). A Facebook page is characterized by a very limited group- and permission-management facilities, which rules out assigning specific permissions to sub-groups of participants. The administrator can set permissions only for the people who like the page (its supporters), without any further level of granularity. Moreover, the Facebook page imposes “the wall” as its main interaction and debating tool. Indeed, it is not possible for the administrator to set a different tool as ‘home page,’ say, the Discussion tool (similar to an online forum) or the Note tool (which can be seen as a sort of blog). The Facebook wall allows for fast and volatile interaction. Each post (and its comments) is easily accessible only for a limited time: the more intense the activity, the shorter this interval. On crowded and popular pages, the driving rhythm leads important materials to quickly disappear. No permalink is provided to allow interested users to retrieve them. The wall is appropriate for giving live news and for people’s microblogging activities, but it is not suitable for deliberating on subtle, sensitive, thorny issues: its use leads to a real restriction on how dialogue can take place. Moreover, a page’s participant-identification policy is inherited from the Facebook environment and cannot be changed or hardened.

In the above case of Popolo Viola, this allowed an anonymous identity such as San Precario to establish and own the movement’s page. But it might also leave room for political provocateurs acting as net trolls. This is what happened on October 1, 2010, when, just as most of the page administrators were traveling to Rome for another national demonstration, several anonymous postings appeared. The anonymous poster had used an avatar including the five-sided, red star that had been the symbol of the Red Brigades in the 1970s. If any violence had broken out in the public square the following day, public opinion might easily have been convinced that the purple movement had fallen into the hands of terrorists! In addition, any change to policies for managing pages or groups carried out by Facebook affects the movement’s power structure. This happened, for example, when Facebook introduced a new rule that allows each page administrator to remove any other administrator, including the creator of the page, who had previously been a sort of super-administrator that could not be removed (Renzi, 2010).

Another Facebook feature that significantly influences communication on a page is worth noting. Currently, several politicians and representatives own a page set up to establish a communication channel with citizens. However, citizens who want to engage in dialogue have to subscribe to the page by clicking on the “Like” button. Thus, regardless of their political opinions and preferences, interested citizens appear among the people who “Like” the politician or representative. The name of this simple feature structures the communication.

These examples highlight what a slippery slope using an existing ‘container’ such as Facebook can be for public organizations or grassroots movements that want to involve people in their activities. The container dictates the rules that affect the democratic structure of the hosted group. Changes motivated by Facebook’s business goals may alter the room for maneuver available to the various roles (founder, administrator, subscriber) in some subtle way that might not be obvious to people of diverse technical ability. Only for some of them is the impact of a technical choice actually clear.

As Gladwell observes (Gladwell, 2010), social media are very effective when social networks are needed to mobilize people. Built around weak ties (Granovetter, 1973) they are effective at spreading ideas and information. However, social media “have real difficulty reaching consensus and setting goals.” (Gladwell, 2010, p. 4) Deliberation requires rich, effective communication infrastructure that can collect and coalesce information, ideas, opinions, and participants from various Web sources into trustworthy, democratic digital habitats. As a response to these issues let us outline a conceptual framework for designing the technology dimension of these online environments.

What Spaces and What Balance among them?

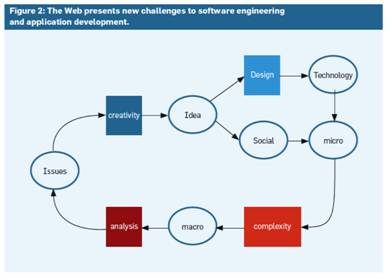

As stated in the Introduction, according to (Winograd, 1996), technology shapes the “spaces for human communication and interaction.” Designing the technology dimension of a deliberative digital habitat thus consists, first of all, of designing online spaces to enable social interactions planned as part of the gemeischaft and gesellscahft dimensions.

In designing a software platform to support online deliberation and assessing it in several real-life settings, we have incrementally tuned the original model presented in De Cindio, De Marco, & Grew (2007). We now believe these spaces should support:

free interaction without a specific purpose that creates a sense of community and mutual trust among participants (community space);

purposeful interaction for achieving, whenever possible, shared outcomes and decisions (deliberative space);

the opportunity for each participant to build visibility, reputation, and ties to others, (essential in motivating people to participate, as the emergence of social networking sites (Boyd & Ellison, 2007) has shown (personal space)); and

gathering, distributing, and sharing relevant content from the other spaces (information space).

Figure 2 depicts these four spaces. Let us note that it represents an evolution of Wenger, White, Smith, & Rowe’s (2005) proposal. In discussing software technologies for communities of practice, they point out the need for tools to be used in cultivating the community (i.e., for designing the community space) as well as the need for tools supporting individual participation (i.e., for including a personal space). It is also worth noting that the community space is very close to what Wright & Street (2007, p. 855-856) call the “‘Have Your Say’ section,” while the deliberative space is what they call “policy forums.” Wright & Street also explicitly envision mixed models that include both kinds of space. The reason is precisely the need to join community space with deliberative space.

The design of the technology dimension should aim at finding a good balance among these four spaces and deciding what functionality each space must provide. For example, a discussion forum in community space, a provision for online citizen consultation in deliberative space, and personal profiles to enhance mutual acquaintance among participants.

What Technology for Each of the Spaces?

These functionalities can be provided in various ways. In the framework for analyzing technology for communities proposed by Wenger, White, Smith, & Rowe (2005), designers:

These choices may be influenced (or sometimes constrained) by prospective participants’ technology profile. For instance, if social inclusion is a relevant issue in organizing a citizen consultation, the designers need to consider the rate of adoption of PCs and mobile phones and choose suitable technology or combinations thereof. Wenger, White, Smith, & Rowe (2005) refer to this situational context as the “configuration of technologies level.”

Of course, existing software tools and platforms, conceived for different purposes and contexts, are often adapted to be reused. However, as noted at the beginning of this section in reference to Facebook, existing solutions may be inappropriate for supporting participation initiatives. Tools to support online deliberation should be firmly rooted in the democratic tradition. For example, a tool that supports structured, synchronous, online debate whose goal is to make decisions (i.e., an enriched chat) should guarantee that a basic property of democratic debate is fulfilled: the majority, if any, is guaranteed the chance to decide, while the minority is guaranteed the right to express its opinions. Thus for example, the Public Sphere Project’s e-Liberate tool (Schuler, 2009) fulfills this requirement by including Robert’s Rules of Order (Robert, 1876) in the software.

OpenDCN was designed within the e21 project precisely for deliberative purposes as an open-source, bespoke platform built from the ground up on democratic principles. The DCN in the name openDCN stands for deliberative community networks (De Cindio, De Marco, & Grew, 2007). It consists of several tools that support various participation modalities, including one that draws inspiration from e-Liberate (De Cindio, Peraboni, & Sonnante, 2008). Note also that a given tool does not necessarily belong to just one space. For example, the openDCN citizen-consultation tool, typically used in deliberation, can also be set up to survey participants’ ideas with the aim of using the results to spur debate or to foster the sense of community.

Which Features Support Effective Public Dialogue?Fostering peer-to-peer, public dialogue among participants is a key factor in establishing a climate of mutual trust. Such dialogue is often missing in Web 2.0 civic initiatives, including open data portals and projects. Comments are typically optional add-ons to posts (as in Caughtya.org and MyBikeLane.com) or to the problem reported (as in FixMyStreet.com and the Iris project). In some cases, comments are not even allowed (e.g., on PatientOpinion.org.uk and RateMyTeachers.com). Thus, as Lovink (2007) notes, there are often “zero comments”. And even when there are, they tend to remain isolated remarks rather than exchanged opinions.

As Wright and Street (2007, p. 853) observe, “online discussion forums can be designed differently — in ways that facilitate deliberation”. We believe that, insofar as possible, these design choices have to be translated into software features and embedded into the deliberative environment to naturally induce people to adopt good practices. For this reason, the openDCN platform’s “informed discussion” tool incorporates the following three features:

The first aims to improve the rationality (Winkler, 2007, p. 188) of the discussion by encouraging participants to “support their arguments with appropriate and reasonably accurate factual claims” (Fishkin & Luskin, 2005, p.40). All the materials attached to posts or directly uploaded by participants are gathered in the information space to provide an organized view of the information resources (video, audio or text documents, links) that support the discussion. Subsequent participants who view the thread can thus access its materials directly. Of course, the development of open data makes new resources available to support rationality. (For example, Tim Berners-Lee’s 5-star system (Berners-Lee, 2009), outlined several levels at which open data can be brought into deliberation. The features embedded in the openDCN “informed discussion” tool support several of them: one can add data documents in any fixed format (e.g. a scanned table); one can make data available in re-useable forms that allow viewers to check the claims made about it; one can link to a data resource available on the web by providing the URL, and that linked resource can then provide context, meaningful names, and annotations of the data (linked open data)).

The second feature concerns interactivity (Winkler, 2007, p. 188) during the discussion itself. Usually, in the classic template of forums and blogs, messages are shown in strictly chronological order, thus losing the thread of the discussion. Answers to specific previous posts do not appear adjacent to the query. To overcome these display limitations, the dialogue tool should allow messages to be presented in indented threads that help citizens visualize how posts and replies are nested, and, if they wish, to put their own comment in the proper location. Interactivity can support conversations around open data, and allow datasets to be enriched with peoples’ comments. A simple example concerns the City of Milan’s press releases: they are published on the municipality Web site without a comment facility. However, when one of them is relevant within an ongoing conversation, the community manager of the partecipaMi web site, posts it in the relevant thread, thus allowing citizens to consider the city news in the appropriate context and to comment on it. When the news is significant per se, and no relevant discussion thread already exists, the community manager opens a new one. Thanks to this, almost all the municipality’s press releases get comments and enrich citizens’ discussions. Unfortunately, from the perspective of civic dialogue those who issued the press releases do not participate in these conversations.

The third feature imports a trait typical of social rating environments and provides (technological) support for what Edwards (2006) calls different styles of citizenship: one “stronger,” more active, and another, apparently “weaker.” An effective dialogue tool should indeed allow citizens to express their (degree of) agreement and to flag posts or information materials they consider relevant. This feature enables people to express agreement or disagreement without forcing them to write a post.

Although developed in advance and independently, it is worth noting that these technical features embed three of the four recommendations proposed by Ramsey & Wilson (2009) to support “the ‘informed’ participant”. Both posts and the information resources attached to them show the author, whose personal profile is available (first recommendation, p. 265). The information space aggregates the resources provided by the various posts. In this way, if controversial views are presented, each participant has access to documents and critiques that support different political positions (third and fourth recommendation, p. 265).

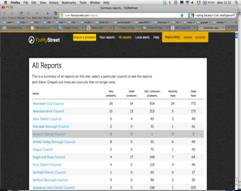

The ability of the proposed framework to foster deliberation can be seen through a direct comparison of the somewhat similar initiatives we have discussed throughout the paper - FixMyStreet, IRIS, and Sicurezza Stradale, the latter designed according to the proposed framework (using the openDCN software platform). All these platforms are, to a significant extent, (problem) data-driven, but the way in which they visualize reported problems is different (cf. Figure 3): FixMyStreet and IRIS do it in table form, while SicurezzaStradale adopts a geo-referential representation on a city map. Fix My Street already generates a feed of open data; openDCN will provide such a feature is the short-term. Access to the dataset collected in these initiatives, and more in general in online deliberation web sites, provide the relevant community and researchers of a valuable wealth of knowledge.

Sicurezza Stradale, went online March 31, 2008 in response to a request from “Ciclobby,” a nonprofit bicyclists’ association, to coincide with the opening of a forum set up by the Milan alderman responsible for traffic. In its first nine months, the site gathered 142 reports from 97 different participants, without domination by any single group or participant. Just over half the reports (i.e., new problems) include comments that reinforce the original post, question it or dispute it, thus assuring interactivity. Both FixMyStreet and IRIS, on the other hand, suffer from the “zero comment” syndrome (Lovink, 2007). On Sicurezza Stradale, 55 of the 142 reports (≈ 40%) include a proposed solution, a phenomenon not found on the other two sites, which simply leave it to the relevant government bureau to solve the problems reported by citizens. Advice, proposals, and related arguments are often illustrated with photographs, attesting to the discussion’s rationality. Pictures, which are not supported by the other two sites, have been used both to document the problem and, in a few cases, even to simulate a solution.

At the end of nine months (on January 13, 2009) a summary of citizens’ reports was compiled and delivered to the alderman in charge of the forum (Gentile, 2009). During that period, a thread in the community space had been used by those involved, (who included the president of Ciclobby, the alderman, and three members of the opposition in the City Council), to monitor progress in the forum, as well as providing the related documentation. After the presentation of the report summary, despite the total lack of feedback from city government, citizens continued to offer advice, although at a slower rate. On November 15, 2009, Milan’s mayor discharged the alderman. Nevertheless citizens continued to inform one another and discuss traffic problems, as well as possible solutions. In one case, citizens organized a petition to force the administration to change a decision: the Sicurezza Stradale site was used to inform them where signatures were being collected. In another case, the information contained in a thread was used by a member of the opposition to present a formal question in her district council: the Web site had been used to monitor progress on the issue. The municipal elections held in June brought a change, with those formerly in the opposition now in charge of governing. A few days after the elections, a citizen’s comment on the site revealed hope that “things will change with the new party in power”.

These vicissitudes show that, thanks to design choices and software features that induce behavior inclined to deliberation, the site is more than an online area where citizens can report problems for local government to fix. It is an environment where, according to changing political conditions, the social actors, and engaged citizens in particular, undertake a variety of actions to cope with traffic problems. From a data oriented perspective, the comparison shows that these design choices and software features support engagement around open data (Davies, 2012) as they enable conversations around data points and promote people’s collaboration around data as a common resource.

This paper introduces the deliberative digital habitat to denote appropriately equipped online environments that support participatory or deliberative initiatives launched by government institutions or by grassroots movements. We have presented a framework for designing such habitats by identifying three dimensions — a gemeinschaft dimension, a gesellschaft dimension, and a technology dimension — and issues critical for each dimension.

While almost all these issues have already been discussed in the literature, what was missing — and what we hope to have provided — is a framework that embeds them and helps digital democracy designers bear in mind significant factors and concepts. Rooted in different disciplinary perspectives and validated by real-life experience, these concepts may be applied to assure projects good initial conditions.

Although focused on design and design issues, this paper represents neither a method nor a handbook. In this it differs from what Kim (2000) offers Web communities, or Wenger, White & Smith (2009) providing digital habitats for sharing knowledge in professional settings (formerly known as communities of practice), or Porter (2008) giving social Web designs through the AOF method (actions, objects, and features). Our work does not provide designers with checklists, tables, and grids to be filled in, but aims rather to outline a more general conceptual framework and a collection of concepts that help foster deliberation in data rich environments among others.

Emerging technologies will challenge the framework’s ability to deal with new concepts, tools, and applications. At the same time, it will be put to the test by the success, failure, results, and setbacks of each specific case, precisely on the basis of the assumption, discussed in the Introduction, that “successful models evolve through trial, use, and refinement.” In so evolving, our framework, we hope, will contribute to understanding how the future Web, in the words of Hendler, Shadbolt, Hall, Berners-Lee, & Weitzner (2008, p. 67), “can encourage more human engagement in the political sphere.” Data — “the web of data” — is an essential part of this effort, and we hope that our work helps researchers, professionals, and activists seeking to use open data as part of a process of democratic engagement while avoiding open data initiatives remaining — as unfortunately it may happen — solely in the technical domain.

Louis Brandeis, a member of the US Supreme Court from 1916, claimed that “Publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman.” (Brandeis, 1914). Recently, several authors, including the US White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs Administrator Cass R. Sunstein, mentioned Brandeis’s claim (Sunstein , 2010) to point out that transparency is crucial for (renewing) democracy. Building deliberative online environments around open data can help in realizing this opportunity.

Beer, S. (1975). Platform for change. New York: John Wiley.

Bellezza, E. & Florian F. 1998. Le fondazioni del terzo millennio: Pubblico e privato per il non-profit. Florence, Italy: Passigli Editori (in Italian).

Berners-Lee, T (2009), Linked Data (slides). Presented at the TED 2009 conference "The Great Unveiling", Long Beach, CA (US), 4 February 2009.

Blumler, J. G. & Coleman, S. (2001). Realising democracy online: A civic commons in cyberspace. London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

Boyd, D. M. & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-mediated Communication, 13 (1), 210-230.

Brandeis, L.D. (1914). Other people's money. Available at

http://www.law.louisville.edu/library/collections/brandeis/node/196

Caddy, J. & Vergez, C., (2001), Citizens as partners: Information, consultation and public participation in policy-making. Paris, OECD Publishing.

Caravita, B. (2002). Internet come gioco a guadagno condiviso. In F. De Cindio (Ed.), Scenari di evoluzione della telematica civica nel contesto di Internet (pp. 20-28). Milan, Italy: A.I.Re.C. (in Italian).

Caravita, B. (2010, February 18). Resistenza a tinte viola. Nòva 24 (Il Sole 24 Ore), p. 23 (in Italian).

Carroll, J. M. & Rosson, M. B. (2003). A trajectory for community networks. The Information Society Journal, 19 (5), pp. 381-393.

Casapulla, G., De Cindio, F., & Gentile, O. (1995). The Milan Civic Network experience and its roots in the town. In Proc. 2nd International Workshop on Community Networking. Piscataway, NJ: IEEE. ISBN 0-7803-2756-X.

Casapulla, G., De Cindio, F., Gentile, O., & Sonnante, L. (1998). A citizen-driven civic network as stimulating context for designing on-line public services. In R.H. Chatfield, S. Kuhn, & M. Muller (Eds.), Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference, Palo Alto, CA: CPSR.

Clinton, H.R., U.S. Department of State, (2011). Internet rights and wrongs: choices & challenges in a networked world (PRN: 2011/217). George Washington University, Washington, DC: Retrieved February 19, 2011, from http://www.state.gov/secretary/rm/2011/02/156619.htm

Coleman, S. (2005). The lonely citizen: indirect representation in an age of networks. Political Communication, 22(2):197-214.

Coleman, S. & Blumler, J. G. (2009). The Internet and democratic citizenship: Theory, practice and policy. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Davies, T. (2012). 5-Stars of Open Data Engagement? Available from: at http://www.timdavies.org.uk.

Davies, T. & Gangadharan, S. P. (Eds.) (2009). Online deliberation: Design, research, and practice. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. Available from: http://odbook.stanford.edu/

De Cindio, F. (2000). Community networks for improving citizenship and democracy. In M. Gurstein (Ed.), Community informatics: Enabling communities with information and communications technologies (pp. 213-231). Hershey PA: Idea Group Publishing.

De Cindio, F. (2004). The role of community networks in shaping the network society: Enabling people to develop their own projects. In D. Schuler, D. and Day, P. (eds.), Shaping the network society: The new role of civil society in cyberspace. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

De Cindio, F., De Marco, A. & Grew, P. (2007). Deliberative community networks for local governance. International Journal of Technology, Policy and Management 7 (2), 108-121.

De Cindio, F., Di Loreto, I., & Peraboni, C. (2008). Moments and modes for triggering civic participation at the urban level. In M. Foth (Ed.), Handbook of research on urban informatics: The practice and promise of the real-time city. Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference, IGI Global.

De Cindio, F., Gentile, O., Grew, P. & Redolfi, D. (2003). Community networks: Rules of behavior and social structure. The Information Society Journal, 19 (5), pp. 395-406, 2003.

De Cindio, F., Krzątała-Jaworska, E, & Sonnante, L. (2011). Problems&Proposals, a tool for collecting citizens’ intelligence. Presented at the CSCW2012 Workshop on Collective Intelligence as Community Discourse and Action, Seattle, WA, 11th February 2012. Availbale at http://events.kmi.open.ac.uk/cscw-ci2012/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/DeCindioal-cscw12-w3.pdf

De Cindio, F. & Peraboni C. (2009). Fostering e-Participation at the urban level: Outcomes from a large field experiment. In A. Macintosh & E. Tambouris (Eds.), Proc. of 1st Conference on eParticipation (ePart 2009), LNCS 5694 (pp. 112–124). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

De Cindio, F. & Peraboni, C. (2011). Building digital participation hives: Toward a local public sphere. In M. Foth, L. Forlano, C. Satchell, & M. Gibbs (Eds.), From social butterfly to engaged citizen: Urban informatics, social media, ubiquitous computing, and mobile technology to support citizen engagement. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (in press).

De Cindio, F., Peraboni , C., & Sonnante, L. (2008). A two-room e-deliberation environment. In D. Schuler (Ed.), Proceedings of Tools for Participation: Collaboration, deliberation, and decision support (pp. 47-59). Palo Alto, CA: CPSR. Available from: http://www.publicsphereproject.org/events/diac08/proceedings/05.E-Deliberation.DeCindio_et_al.pdf

De Cindio, F. & Ripamonti, L.A. (2010). Nature and roles for community networks in the information society. AI & Society, 25 (1), 265-278.

Della Casa, G. (1558). Il Galateo. (Known also in translation: Fitzherbert, N. 1595. Ioannis Casae Galathaeus sive de moribus liber Italicus, Rome).