The Nature of Hybrid Community: An Exploratory Study of Open Source Software User Groups

- Associate Professor, Department of Information Systems, College of Business, San Francisco State University, United States. Email: jinlei@sfsu.edu

- Professor, Department of Computer Information Systems, Robinson College of Business, Georgia State University, US.

- Associate Professor, Department of Management Information Systems, Terry College of Business, University of Georgia, US.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, Free/Libre and Open Source Software (FLOSS) development has captured the attention of both information systems practitioners and researchers. Traditionally, the software market is dominated by proprietary, or closed-source, software. Its end users have to pay for the right to install and use the software. Its source code is "nearly always hidden from view as a technical matter, and as a legal matter it cannot be used by independent programmers to develop new software without the rarely given permission of its unitary rights holder" (Zittrain, 2004).

In contrast to proprietary software, FLOSS is a broad term that refers to software that is developed and released under either a "free software" or an "open source" license. Crowston et al. (2006) highlight similarities and distinctions between the free software and open source movements. Both types of software are usually developed through collaboration among volunteer members of communities that are geographically distributed, and allow users to obtain and distribute the software's source code without charge. Where the two diverge is primarily in the level of "freedom" granted in their licensing terms concerning modification and redistribution of the software. The free software movement, for example, strictly enforces the "copyleft" license, which stipulates that "anyone who uses and releases the copylefted code as a component of new software must also release that new software under copyleft's otherwise permissive terms" (Zittrain, 2004).

Over the years, FLOSS has thrived and grown into a platform that poses serious competition to the proprietary software market (Sen 2007). Big vendors such as Google, IBM, HP, and SAP, to a certain degree, all embrace and adopt FLOSS development. Researchers have sought to explain the counterintuitive practice of treating commercially valuable products as public goods rather than proprietary products for sale (von Hippel and Krogh, 2003; Schaarschmidt, Walsh, and von Kortzfleisch, 2015). Likewise, the development and maintenance of complex software products by communities of expert volunteers has stimulated interest into the incentives for developers (Hertel et al., 2003) and modes of governance (Teigland et al., 2014).

Although the majority of the research conducted on open source software has focused on the phenomenon of software development (Fitzgerald and Kenny, 2003), attention has been drawn increasingly to FLOSS use (Jin, Robey and Boudreau, 2007; Waring and Maddocks, 2005). The availability of free and reliable software products has attracted users interested in lowering or eliminating the costs of software licenses and upgrades (Fitzgerald and Kenny, 2003). Also, the emergence of commercial ventures leveraging open source into a profitable value proposition has increased the number of organizations considering open source for key components of their infrastructure (Fitzgerald, 2006; Teigland et al., 2014). "Second generation open source" could emerge as the dominant model for open source development, and seduces even the most skeptical potential adopters (Watson et al., 2008). In fact, it was estimated that the majority of open source development was supported by vendors that offer commercial products and incorporate open source software (Violino, 2004). Hauge et al. (2010) suggests that FLOSS has inspired software companies not only to improve their existing development processes, but also to have their development efforts collaborate internally as well as across company borders. The potential benefits of embracing FLOSS include: faster adoption of technology, increased innovation, and reduced costs and time to market (Bonaccorsi and Rossi, 2006). In addition, FLOSS has played a crucial role in leading the software industry away from the traditional license-based business models towards service-based models (Fitzgerald, 2006). Undoubtedly, FLOSS is profoundly influencing the ways that organizations develop, acquire, govern, use, and commercialize software (Ebert 2009; Hauge et al 2010; Schaarschmidt et al., 2015).

The shift in focus to FLOSS users seems appropriate for several reasons. For widely popular FLOSS such as Linux, the number of users greatly exceeds the number of developers. Moreover, as FLOSS development becomes increasingly targeted toward productivity and entertainment applications, an increasing number of non-experts are becoming FLOSS users. Although some users may participate actively in software development, the vast majority of users have no interest or capability to contribute to modifications of the source code (Fitzgerald and Kenny, 2003). This could be especially true for open source projects that involve high "contribution barriers" (Krogh, Spaeth and Lakhani, 2003)1 . Compared to the use of proprietary software, FLOSS use presents novel challenges because of its fundamentally different type of technical support (Jin et al., 2012). Rather than relying on a vendor's customer support, users of FLOSS need to find other sources of help for installing, learning, and using their freely acquired software.

In this paper, we study FLOSS user communities. We adopt a community perspective on FLOSS use because community governance is fundamental to FLOSS development. Although much commercial interest has centered on providing FLOSS users with support and service (Watson et al., 2008), FLOSS users may also receive support through participation in user groups of community volunteers, similar to the communities supporting development (Fang and Neufeld, 2009). We also expect that FLOSS user communities for software acquisition, implementation, maintenance, and support would be largely virtual, like FLOSS development communities. Research on FLOSS use supports this expectation. Lakhani and von Hippel (2003) found that successful open source projects delivered field support to users through voluntary efforts of experienced users answering questions posted by new users on archived mailing lists. Indeed, a highly organized system of FLOSS user groups has sprung up around the major FLOSS products. The popularity of Linux has also created a trend by which many leading IT vendors attempt to link their commercial offerings with open source technologies, and to spin off open source user communities to help them boost revenues or reduce costs (Violino, 2004).

Despite the prevalence of electronically mediated interactions among FLOSS users, FLOSS user communities are not exclusively virtual. User groups are frequently located in specific geographic regions, permitting members to attend regularly scheduled meetings and to discuss common issues face-to-face (Moen, 2006). For example, The Silicon Valley Linux User Group (LUG), one of the oldest and largest LUGs in the world, holds face-to-face meetings at least monthly. For its first 10 years, the Silicon Valley LUG met in the back room of a local restaurant. Later, as the membership expanded, meetings were moved to rooms donated by companies like Cisco and Symantec. Among the face-to-face activities that LUGs perform for users are InstallFests, where experienced volunteers install Linux on new users' computers, diagnose problems, and repair configurations. The LUG of Davis, California operates a Linux Emergency Relief Team that provides assistance in new users' homes. Because they operate both virtually and physically, FLOSS user groups may be considered as "hybrid" communities, relying upon both computer-mediated (virtual) and face-to-face (physical) means for communication. Our section on Background Literature reveals that little is yet known about the relationship between virtual and physical activities in hybrid communities.

Understanding hybrid communities is relevant to a larger range of social activities beyond the use of open source software. Web 2.0 refers to a set of web based services that aim to facilitate collaboration among a large number of users with shared community interests and activities (O'Reilly, 2005). Web 2.0's social networking technologies have contributed to the proliferation of websites like Wikipedia, YouTube, MySpace and FaceBook. Tapscott and Williams (2007) use the term "Wikinomics" to describe the business value that such mass collaboration can generate through engagement with a global peer network. Rather than turning to traditional organizations, more users look toward peer relationships to satisfy their needs (Li, 2007). Some of these ventures operate as hybrid communities. For example, Facebook's online service enables users to reinforce established social relationship and to participate in local community groups or events. Gabbay (2006) attributes the success of Facebook to "providing pre-existing offline community with a complementary online service." Thus, Facebook communities resemble hybrid communities more than pure online communities. In addition, the hybrid communities may play an even more important role in the recent trend of "SoLoMo", referring to the convergence of social, local and mobile media and services, which enables businesses to offer highly customized products/services at the right moment, with the right price, and through both online and offline channels (Davenport et al., 2011). This suggests that by leveraging the user communities associated with their products and services, businesses are in a better position to innovate. In fact, recent research suggests that an "open, uncoordinated group of users can be as or more efficient than specialized producer innovators"(Hienerth et al., 2014, p.199), thus suggesting "open innovation" as a successful model.

The very notion of "open innovation" is greatly inspired by the FLOSS movement (Goldman and Gabriel 2005; Huizingh 2011). It is based on the assumption that innovation itself is a distributed process that may take place outside the boundaries of organizations and social groups (Chesbrough et al. 2008, Chesbrough 2015). It is suggested that traditional development practices are not well adapted to managing distributed innovation in the new technology era (Goldman and Gabriel 2005; Ghesbrough et al. 2008). Instead, "user centered design" and agile development methodologies are more suitable to facilitate open innovation (Humayoun, 2011; Pratt, 2012). In recent years, advancements in smartphone and mobile technology has provided end users with unprecedented opportunities to connect, collaborate and engage in innovative processes, to start new business models, and to bring social change (Chesbrough, 2015). Meetup.com, for example, is an online social networking portal that connects the world's largest network of local groups that meet face to face. Since it was founded in 2001, it has enrolled 21 million members in 180 countries, who join 198,000 meetup groups and participate in over 528,000 monthly meetings. Their website and mobile application make it easy for anyone to start, find, and join local groups based on common interests, such as technology, careers, hobbies, politics, books, and health, etc. (meetup.com).

These developments suggest the relevance of studying hybrid communities, i.e., those that exist both online and offline. Our research employs a qualitative research methodology to understand how hybrid FLOSS user communities utilize both virtual and physical representations to extend their capabilities and to provide support for non-technical users. We begin by reviewing the literature on virtual communities and hybrid teams, which together suggest that communities may also operate as hybrid work systems. We then draw from a theory proposing a dual ontology of work that includes both virtual and physical representations of teams and organizations (Robey, Schwaig and Jin, 2003). We extend the dual ontology to the community level to focus upon the relationships between virtual and physical representations of the Linux user community. Our findings suggest that virtual and physical representations of a FLOSS user community complement each other, thereby extending the capabilities of the community.

BACKGROUND LITERATURE

Virtual Communities

Since the dawn of the Internet, people have extended their ability to communicate and to engage in productive activities despite being separated by geographic distance. Information and communication technologies have thus facilitated the emergence of virtual communities. Taken literally, virtual means "being such in essence or effect though not formally recognized or admitted."2 The literal meaning of virtual reflects its use in computer science to describe virtual machine environments and its use in science fiction where concepts like virtual reality were born. Although the term "community" originally referred to a group of people living in a common geographical location, people have grown more accustomed to participating in virtual communities that are enabled by Internet technology and the World Wide Web (Shumar and Renninger, 2002). Virtual communities may exist simply for entertainment value, or they may be organized to govern economic activities such as FLOSS development and use (Adler, 2001).

Virtual communities remain a source of fascination and controversy among social scientists. Views range from highly optimistic evaluations of new possibilities for social interaction, especially the mobilization of people who share interests but are not geographically close. Virtual communities are seen as attractive because they offer a wider range of options than co-located communities. For example, they allow communities to grow in size, unconstrained by physical space. Individual members may also tailor their virtual communities to satisfy personal preferences (Wellman, 2001). More pessimistic assessments question the ability of people who never meet face-to-face to form true communities based on trust. Indeed, due to the potential for assumed identities in virtual communities, community members can be more easily deceived. The prevalence of fraud in online auctions provides partial evidence that trading is more susceptible to criminal deception when trading communities are populated by sellers and buyers whose true identities remain unknown (Chua, Wareham and Robey, 2007).

Much of the literature about virtual communities demonstrates that virtual communities meet the criteria used to define face-to-face communities, thus validating the claim that virtual communities are true communities. For example, communities are defined as human collectives that:

- share interests (Parrish, 2002; Baker and Ward, 2002; Hampton, 2002)

- believe in the value of cooperation as a means to advance those interests (Kollock and Smith, 1996)

- share a means of communication (Parrish, 2002; Etzioni and Etzioni, 1999)

- form affect-laden bonds (Etzioni and Etzioni, 1999)

- hold commitments to shared values, norms, meanings and identity (Etzioni and Etzioni, 1999)

- have access to shared memory (Etzioni and Etzioni, 1999)

- share either place or space (Driskell and Lyon, 2002)

- exercise sanctions to govern community action (Baker and Ward, 2002; Kollock and Smith, 1996; Etzioni and Etzioni, 1999).

By demonstrating that virtual communities possess these same defining characteristics, this literature establishes that virtual communities qualify as true communities.

However, this literature implies that communities are either co-located or purely virtual, neglecting the issue that communities might be only partly virtual. With few exceptions (reviewed below), the literature on virtual community does not embrace the idea that a community could be represented both virtually and physically, that is, as a hybrid community. In the following section, we examine the concept of hybrid organization as applied to teams and propose that this same conception can be applied to understand communities.

Hybrid Communities

The term "hybrid" is used in the literature on teamwork to describe teams that use both remote and face-to-face communication (Fiol and O'Connor, 2005). Hybrid teams fall between the extremes of never meeting face-to-face and always meeting face-to-face. In hybrid teams, members may be co-located yet rely on both face-to-face and electronic communication on a daily basis (Zack, 1993). Hybrid teams may also be geographically distributed and meet on rare occasions (Cousins, Robey and Zigurs, 2007; Maznevski and Chudoba, 2000). In effect, hybrid teams are represented in two overlapping and/or alternating forms: one physically situated in time and space, and one virtually mediated by electronic communication (Lilly, Lightfoot and Amaral, 2004). Given these multiple representations, hybrid teams face different challenges than those faced by either purely virtual or purely face-to-face teams. These challenges include member identification (Fiol and O'Connor, 2005), developing and transferring organizational knowledge (Griffith, Sawyer and Neale, 2003), managing conflicts (Hinds and Bailey, 2003), and making decisions (Maznevski and Chudoba, 2000). However, hybrid teams overcome some of the limitations experienced by purely virtual teams. For example, Dubé and Robey (2008) found that face-to-face meetings play important roles in supporting distributed work and that face-to-face meetings address numerous contradictions associated with virtual teamwork.

The issues facing hybrid teams may also apply to communities that operate virtually while also sometimes meeting physically. As mentioned in our introduction, communities of FLOSS users also have opportunities to meet face-to-face, even though much of their communication remains virtual and is conducted via electronic media. Thus, it seems appropriate to apply the concept of hybrid organization to communities as well as teams. Like hybrid teams, we expect that hybrid communities would face both challenges and opportunities stemming from combining their virtual and physical representations.

To study hybrid FLOSS user communities, it would be helpful to draw from theory at the community level that acknowledges their hybrid characteristics. Unfortunately, with few exceptions, the community literature tends to assume that communities are either virtual or physically co-located. The exceptions found in our review of the community literature fall short of offering a sound theoretical basis for guiding a study of FLOSS user communities. For example, Fox (2004) argues for a "community embodiment model" in which both physical and virtual activities, interactions and identity are combined in the imagination of community members. The imagined community embodies a continuum of virtuality/physicality, a communal spectrum that is essentially socially constructed by community members. While this idea addresses the issue of community identity, it falls short of explaining how communities might benefit or suffer from their hybrid nature. Other studies are purely descriptive, suggesting ways in which physical communities can expand to become hybrid (e.g., Gaved and Mulholland, 2005). Others treat FLOSS communities as hybrid teams and employ constructs from the team level of analysis to study interactions among community members (e.g., Crowston et al., 2007).

The theory guiding our investigation of open source software user communities is drawn directly from a conception of work proposed by Robey et al. (2003). Recognizing that work at multiple levels of analysis (individuals, teams, organizations, markets, and communities) is increasingly represented both physically and virtually, Robey et al. propose a dual ontology of work. Drawing from concepts of virtuality found in computer science and science fiction, they conceptualize work to include an electronically mediated, virtual representation and a material, physical representation. The virtual representation is comparable to the notions of cyberspace and virtual reality (Benedikt, 1992; Turoff, 1997). Thus, a virtual representation of an organization would consist of electronically mediated processes, such as accounting, represented abstractly by computers and not confined to specific locations (Sotto, 1997). By contrast, the physical representation would consist of people and physical objects situated in specific places. Although virtual representations typically refer to physical or social objects, for example as mathematical symbols, virtual representations do not need to faithfully match the physical shape or geographic location of material objects. Virtual representations are not merely electronic copies or analogues of the physical entities. Rather, virtuality offers the potential to reconstruct and "re-present" physical objects in ways that are unbound by physical constraints (Sotto, 1997; Turoff, 1997).

Because work includes both of these representations, Robey et al. (2003) draw attention to the relationship between virtual and physical representations. They argue that a dual ontology "draws attention to neglected issues in the design, performance and outcomes of work. … [It] draws attention to the relationship between the two representations and the need for virtual and material work to be effectively intertwined" (Robey et al., 2003: 118). The theory examines potential disconnections between virtual and physical work and proposes specific ways in which the disconnections can be overcome. Robey et al. base their analysis on the metaphor of intertwining because "…intertwining of distinct elements augments the performance of individual elements by creating, for example, greater strength and beauty" (p. 118). Intertwining also means that material and virtual representations of work are mutually engaged, so that each representation's contribution depends on its reciprocal involvement with the other. They propose four types of relationships between the dual representations of work: reinforcement, complementarity, synergy, and reciprocity.

In this paper, we focus on complementary relationships due to their salience in our data. As noted in our Method section, we coded for all four aspects of the relationship, but evidence for the other three aspects was not sufficient to support a credible analysis. In a complementary relationship, two intertwined elements provide characteristics that compensate for the other's shortcomings. For example, virtual relationships provide capabilities to communicate at great distances and provide access to electronically stored resources. These capabilities complement the characteristics of physical communication, which has its own strength of providing nonverbal cues that compensate for a recognized deficiency in electronic communication. Together, virtual and physical representations complement each other.

Although Robey et al. (2003) restrict their illustrations to teams and organizations, they speculate that other forms of work such as markets and communities could also be conceived in terms of a dual ontology. Our purpose in this paper is to use the dual ontology approach to gain insights into the relationships among the physical and virtual representations of hybrid communities, specifically FLOSS user communities. These communities interact extensively online, but they also hold physical meetings in specific locations. They thus provide an opportunity to examine how these two types of community representation intertwine and how the combining of these representations can extend members' capabilities.

METHOD

We undertook an exploratory approach in our research using the theory as a lens for interpretation. We remained open to discovering the empirical indicators of the theoretical concepts rather than specifying them a priori. In addition, we assumed that the theoretical concepts would be revealed through social interpretations by actors in communities (Klein and Myers, 1999). An interpretive approach to research assumes that constructs do not exist in a truly objective sense but rather are generated inter-subjectively by actors. This assumption guides an empirical research strategy of engaging researchers and actors in qualitative interviews and by observing the behavior of community members both online and in face-to-face gatherings. Participant observation also helps the researcher to contextualize comments made during interviews.

Since August 2002, one of the authors began regularly attending monthly face-to-face meetings in five LUGs around Silicon Valley and the San Francisco Bay area. This involvement allowed her to participate in and observe the activities of members at different LUG meetings, varying in size from 15 to 300 attendees. As a participant-observer, she actively engaged in FLOSS related activities both online and offline, including subscribing to the mailing lists of different LUGs, attending monthly meetings, recording presentations, recording field notes, interviewing LUG members and meeting presenters, and attending social gatherings at local restaurants following the meetings. As the researcher became more involved in observing FLOSS-related activities, she also became an active participant in FLOSS communities.

This paper draws upon interviews as the primary source of data. Arranging interviews was achieved by attending LUG meetings that involved an invited speaker presenting a particular FLOSS topic. At the meeting, the researcher introduced herself to the attendees, including the speaker and LUG officers. During the interviews with LUG officers, she asked them to identify other key members in the LUG as interview candidates. In addition, she found that LUG mailing lists served as an excellent source for selecting potential interviewees. The most active members, who posted regularly on the LUG mailing list, were also contacted for interview opportunities. In total, 20 semi-structured face-to-face interviews were conducted and subsequently transcribed for analysis. The interview protocol used is presented in the Appendix.

The two other authors analyzed the 20 interview transcripts. Each interview transcript was coded according to the different categories of intertwining described earlier (reinforcement, complementarity, synergy, and reciprocity). Specific codes were created a priori to capture the intertwining of the physical and virtual representations: how a representation reinforced the other, how a representation complemented the other, how there was synergy between the representations, and how a representation reciprocated another. To be considered for coding, a text segment needed to clearly represent one of these four aspects of intertwining.

Initially, the two researchers coded the same group of five interview transcripts to assess the similarity of their understanding of the meaning of the coding categories and the text segments that represented them. The coders discussed and reconciled instances of disagreement. More precise rules were established for a second group of two interview transcripts, which were also coded in parallel by these two researchers. Given a much higher level of agreement for the second set, the remaining 13 interview transcripts were coded separately by both researchers.

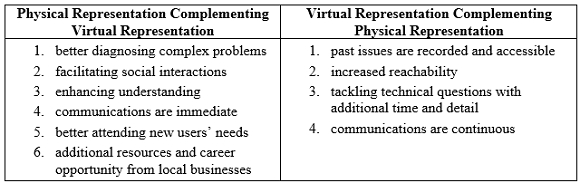

RESULTS

Our research reveals that the virtual and physical representations of the Linux user community were intertwined in one significant manner: through complementing each other. Although we found some instances where the representations intertwined through reinforcement, synergy, and reciprocity, those instances were few compared to the complementarity existing between the representations. Complementarity exists when the unique characteristics of one representation compensate for the weakness of the other representation, and vice versa. In this study, we observed that on some dimensions, the physical representation complemented the virtual representation, whereas on others, the virtual representation complemented the physical representation. These results are summarized in Table 1.

Physical Representation Complementing the Virtual Representation

Our findings reveal that the physical representation may complement the virtual in six specific ways. First, in the physical representation, complexity is tackled better. For example, the installation of the Linux operating system on an unfamiliar machine or device can be a very complicated task. To undertake such challenges, many LUGs have a regular event called the InstallFest, where users are invited to bring their own machines or devices and seek help to set it up with Linux. Such a task could hardly be done virtually, considering its ad hoc, and potentially very complex, nature. Some users explained:

"We get people who turn up with […] quite bizarre, strange PCs that are very difficult to install on… So if they bring their machine along, then you end up with the collective brains of 20 people trying to get this working. And sometimes you'll get one person who'll come over and try and help, and it won't work, so somebody else comes along, and eventually you'll find someone who's done it before or knows something about it and will get it working."

"Online, all you can show is words. If someone comes to a meeting, you can actually demonstrate something to them that they wouldn't otherwise have been able to see - or not easily."

A second way the physical representation complemented the virtual one was in the social interaction that was more prevalent in the face-to-face context. According to our respondents, social interaction may not come easily for highly technical people, but it is a very important element that is facilitated through face-to-face meetings:

"Nerds in general aren't well known for being social people. They tend to shy away from large groups. But something about a large collection of nerds in one place seems to work, for certain ones."

"It's the whole social interaction thing. You talk to people face-to-face. It's not the same as online, really. Geeks have a tendency not to be particularly social with the general community, so for me and a lot of others, this is a good place to meet people that they can sit down and talk to for awhile about things and not bore somebody's head off about something they don't care about."

Some members choose to attend LUG meetings despite disinterest in the presentation topic because they enjoyed getting together with friends.

"The real reason I come is to meet these people and afterwards go to IHOP3 and talk for hours, until almost midnight. And that's what we all enjoy the most."

Social interaction, we were told, was quite important and often led to long lasting friendships and even marriages.

A third way of complementing is related to the formal presentations (guest speakers) that regularly occurred during LUG physical meetings. Although users generally had access to presentation slides online, most of them found that physically attending the presentations allowed them to get the full story, i.e., a better understanding of the subject being presented:

"I can look at the slides, but it doesn't really tell the whole thing. There are questions and things that people say that I cannot really get the same from online."

A better understanding also resulted from the fact that a face-to-face setting facilitated richer communication than online. It was easier to convey emotions (such as excitement, enthusiasm, or even sarcasm) face-to-face than online. It was less likely that a face-to-face communication would be misinterpreted than comments made online:

"People are more inclined to take things the wrong way in email than they are in person. So there's something about email that makes things seem like an argument and there's something about talking in person that makes things seem more like a discussion"

Communication was also improved because face-to-face interactions had greater bandwidth than online interactions. That is, more was said in a given time period. One user characterized electronic communication as follows:

"It's basically like trying to suck water through a straw: you can only get so much through at a time. At some point in time, if you're really thirsty or you burn your mouth and you want to get more water, you take the straw out and you tip the glass up to your mouth and you drink from it. You can get a lot more that way... and it's just easier to convey thoughts a lot quicker and a lot faster [face-to-face] than trying to type them out."

A fourth way that the physical representation complemented the virtual one was that the physical representation provided immediacy in the communication. During a meeting, when asking questions about a problem, users got instant responses rather than having to cope with potential delays related to being online:

"…if we're sending e-mails, that might take us half the day because we're each doing other things rather than just sitting there in front of our computers waiting for that e-mail to come in and then quickly responding to it. Even if that was the case, it still takes time because it takes time for the e-mail to get from here to there and for it to get from the server to my desktop. So there's definitely a delay there"

Interestingly, while other online communication media such as instant messaging or chat may potentially provide better immediacy than email, mailing lists remains the most popular online channel across different LUGs. We suspect this is because email is less invasive compared to online chatting; since most LUG members have day time jobs, they may not be able to participate in online chatting as much as email.

Fifth, a physical setting compensated for the virtual representation's tendency to intimidate novice users. Indeed, in a face-to-face setting, users felt more comfortable asking basic questions that might be considered "dumb" in an online forum. Two users commented:

"Some people are intimidated about sending email to a general list that reaches, you know, a hundred people or whatever"

"It could be really helpful when you are starting, there is one person you can just go and ask trivial questions with, because you might find comfortable just finding somebody instead of putting dumb questions online, it is just much easier."

Because of its less intimidating nature, the physical representation was particularly effective in recruiting new users and integrating them into the FLOSS community. In fact, many meetings were organized to attract and retain novice users, or "newbies." Not only did experienced users help new users in solving their specific problems at physical meetings, but newbies also learned something unexpected, like stumbling into a conversation on a piece of software or utility they had not heard of before. As one user said:

"There's just the random information that you can pick up from people who you run into there."

Finally, the physical representation helped to build ties with local businesses, providing community members additional resources and career opportunities that were difficult to harvest through the virtual representation alone.

"We get a lot of contributions of books from publishers like… O'Reilly Associates, and we randomly get magazines from Linux Journal, and other publishers will sometimes send us stuff… Or other companies that are doing Linux-related things who are trying to spread awareness of their products, they'll ship us a demo, or they'll ship us some brochures which we'll mention at the meeting and we'll give out to people who are interested in them."

LUG meetings also offered direct access to a pool of technically skilled people who were not bound to withhold details of proprietary software code. Given the scarcity of such talent, local companies used the LUG meetings for prospecting. Some LUGs even set up "job corners" for local companies to recruit LUG members. One user claimed to be hired the second day after he was laid off by his previous employer. Another user from a large employer commented:

"It is a really good way for people to get the resources they needed. I always told my boss, hey, if you want, you can come here and collect resumes yourself."

In sum, the physical representation of the Linux user community compensated for many of the weaknesses of virtual interaction. Specifically, it provided a physical setting in which: 1) complexity was better addressed, 2) social interactions were facilitated, 3) understanding was enhanced, 4) communications were immediate, 5) new users' needs were better attended, and 6) ties with local businesses were cultivated.

Virtual Representation Complementing the Physical Representation

The virtual representation, in turn, also had a number of strengths to compensate for the weaknesses of the physical representation. From our data, we identified four specific ways in which the virtual representation complemented the physical representation. First, virtual media provided access to past issues, as each email exchange that occurred (through the listservs) was archived. The importance of tracking past communication was emphasized by two users:

"If I have a problem, and I get an error message, if I go to Google, put the error message in, I will find mailing list archives where people have discussed this, someone might even say the same thing that I have got a problem, and then there will be an answer immediately after, I try that, hey, it works. And now, that was not even someone going out to create a document on the web, that was just two people having a conversation, and I have just tapped to a conversation that two people had three years ago, and it is on the other side of the world. In fact, we even had it in other languages."

"So actually there is a disadvantage helping people in person then, because their solutions are not captured. I never thought about that, but that is true, if you do help somebody in person that is lost data, you help them and you show them but what you invested in helping that one person is lost for everybody else."

These comments illustrate an obvious strength of the virtual representation that is unbound by time or space. Thus, a user's question posted in the middle of the night could be considered immediately by users located in different time zones. Access to archived materials allowed users to search for information about a specific problem prior to inquiring for help.

A second way that the virtual representation complemented physical interaction was the increased number of people that were reachable. For all users we studied, the online community reached many more people than the face-to-face meetings. Because it was easier for users to be online than to physically attend a meeting, it was not surprising that virtual users outnumbered co-located users. Consequently, the chance for a given request to be answered was likely to be higher within the virtual representation:

"When you're in a room asking people, "What utility is good for this," you'll get responses from a lot more people, but they may not be as well formed responses. And you can contact a lot more people via e-mail on our lists"

A third way to complement dealt with the nature of interactions. Just as the physical meetings dealt better with social issues, some technical issues were more easily addressed virtually. While inquiring for help online, it was possible for a user to post or attach configuration files, log-in trees, snippets of code, screen shots, error messages, and other relevant information that was too long to describe verbally or to jot down on paper. With information that was cut and pasted or forwarded using the virtual channels of communication, expert users could more easily evaluate a problem and offer solutions.

"Anything that involves handling a text, where you need to have some documentation or a lengthy account of some symptoms that you observe or something like that... It's much more effective to handle that using on-line mechanisms."

Responding to requests in the virtual representation also allowed experts more time to research a problem, to explore and test solutions, and to explain the rationale for a solution in more depth. Sometimes, the same benefits applied to users who posted questions seeking online help. When they detailed the specifics of their problems in writing, they were more likely to describe it thoughtfully. In the best case, going through this exercise resulted in users resolving their own problems. In one of our respondents' own words:

"When you explain your code to someone else, you have to explain the code to yourself again, and then you may realize you wrote something stupid […] If you spend the time to go through everything you did and explain everything…, it's quite likely you're gonna find the mistake while you're typing the e-mail."

Finally, the continuity of communications was greater in the virtual representation than in physical settings. Although communication within face-to-face meetings were more immediate, as argued above, virtual discussions continued during the weeks and months that separated physical meetings. Thus, a user did not have to wait for the opportunity to pose a question or provide a response at a physical meeting. One user commented:

"I think if you are doing something and you have a question right away, or technical problems but you cannot figure out, and you need an answer to it, if you have to wait for a month [for a face-to-face meeting], that is not good. So, having that immediate feedback, being able to ask questions online, it is good."

Overall, the virtual representation had the capability to compensate for many of the weaknesses of the physical representation. Specifically, it provided a setting through which: 1) past issues were recorded and accessible, 2) reachability was increased, 3) technical questions were easier to tackle, and 4) communications were continuous.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Our results suggest that a dual ontology is a useful conceptual approach to studying hybrid communities. Distinguishing between virtual and physical representations of the Linux user community provides insight and invites evaluation of the activities pursued within each area of community life. More importantly, our approach supports the investigation of the relationships between virtual and physical representations. Although different in several fundamental respects, the dual representations of community intertwine in ways that, according to our analysis, help to extend the capabilities of the FLOSS user community. As community governance principles become more frequently applied to activities with economic implications, as with FLOSS development and use (Schaarschmidt et al., 2015), finding ways to increase community capabilities becomes a strong motivation for community researchers (Adler, 2001). Drawing on theoretical analyses of teams and organizations (Robey et al., 2003), we examined ways in which virtual and physical community representations are intertwined and, consequently, offer opportunities for hybrid communities to extend their capabilities. Complementarity is consequential because of its positive effects on solving complex problems, such as those encountered by novices in trying to use FLOSS products. Analyzing complementary relationships between virtual and physical representations of the Linux user community draws attention to the strengths and weaknesses of both representations. Our results demonstrate several ways in which the strengths of one representation compensate for the weaknesses of the other, supporting the theory's expectation (Robey et al., 2003). For example, from our results, it is clear that virtual community representations allow for more thoughtful and more thoroughly researched problem solving, while physical interactions allow more accessible and friendly opportunities for novice users to seek advice on problems related to Linux. Clearly, both capabilities are important and together they complement each other to enhance the aims of the hybrid Linux community.

Our study suggests some implications for the design of hybrid communities, notably that the concept of "design" must be used cautiously in reference to communities because communities differ from teams or organizations that are more likely to be governed by rules enforced by a hierarchy of authority (Adler, 2001). In communities, governance tends to be diffused throughout rather than controlled by central designers or people empowered to enforce the chosen design. Nonetheless, FLOSS communities do have sponsors and leaders, and face-to-face events do need to be planned, organized and orchestrated by specific community members.

For those charged with leadership responsibilities, the most fundamental design implication to be drawn from our research is that care must be taken to ensure that activities are allocated across virtual and physical representations in ways that strengthen community capabilities. Activities designed within the face-to-face representation of the community can complement the virtual representation, and vice-versa. Given that most FLOSS users that we met were active both online and in the LUG meetings, they were probably most aware of the need for intertwining virtual and physical activities. With more explicit attention to the different ways in which intertwining might be achieved, FLOSS community members might forge even stronger and more creative capabilities in their collective endeavors.

In more direct terms, FLOSS community leaders should carefully establish and manage both physical and virtual representations of the community at large. Although more effort must be expended to organize and promote face-to-face meetings, physical interaction is important for FLOSS communities to attract new users, to facilitate learning and problem solving, and to gain additional resources and support from local businesses. These activities also provide less technical users with more opportunities to participate in the FLOSS community. For a healthy hybrid FLOSS community, we suggest that both its offline and online activities be coordinated with each other.

When designing activities for hybrid FLOSS communities, we surmise that there is also potential for other types of intertwining between physical and virtual representations. Synergistic, reciprocal, and reinforcing relationships were rare enough in our data that we did not mention them in our results. Nevertheless, we contend that they are important and other settings may provide a more fruitful ground to explore these types of intertwining. For example, through reinforcement, virtual and physical community representations may strengthen existing capabilities by providing multiple ways for community members to interact. Reinforcement may help to strengthen the social ties between members, who may have a greater level of understanding of, and attraction to, other members when opportunities to meet other members face-to-face materialize. This idea would support the findings of Crowston et al. (2005), one of the few studies to examine the physically situated relationships among FLOSS developers.

In acknowledging the limitations of this research, we first note that the results of our study rest upon interview data generated by a relatively small number of members of geographically proximate Linux user groups. As such, the findings may be subject to the influence of local culture and the high technology environment of Silicon Valley and surrounding areas. They may not be applicable to Linux user groups in other geographical locations or in other countries, much less hybrid communities devoted to other causes. Second, we acknowledge the limitation of our qualitative research method, which does not permit a more systematic analysis of community network structure. Given that a majority of LUGs preserve mailing list content digitally, it would be possible to employ social network analysis to explore the structure of user groups' virtual interactions. However, since the local LUGs we studied did not keep attendance records of face-to-face meetings, we were unable to construct a social networking analysis that included both virtual and physical relationships. Thus, a limited social network analysis would not have contributed additional insight into our research question, although we acknowledge that such analysis could enhance our understanding of the social relationships among hybrid user group participants. Third, our data reveal the positive aspects of complementary physical and virtual representations, and do not represent any negative aspects. Clearly, investing resources into intertwining virtual and physical community representations may not be feasible for hybrid communities with limited resources. Given the potential value of FLOSS, however, we feel that such investments may result in consequences that are highly valued. Not only would developers of FLOSS see more vindication of their efforts, but members of FLOSS user communities would reap more benefits from their ability to apply FLOSS to their business applications.

ENDNOTES

1 "Contributions barriers" involve four

dimensions: (1) the difficulty in changing code; (2) the

variability in computer language; (3) the difficulty of

"plugging" code; and (4) the coupling between sections of

code. The greater each of these dimensions is, the

greater the contribution barrier.

2http://www.m-w.com/dictionary/virtual

3 IHOP stands for International House of

Pancakes, a chain of restaurants typically open 24 hours

a day and specializing in American-style breakfasts.

REFERENCES

APPENDIX

Interview Protocol:

Introduce researcher and goal of the research.

Ask for permission to record.

Start with questions:

- Demographic information about the respondent

- When/why did the respondent start using Open Source Software?

- When/why did he/she join the LUG mailing list?

- When/why did he/she start attending local meetings?

- What is the brief history of the particular LUG?

- Compare and contrast experiences with using online communication channels, such as the mailing list or Internet Relay Chat, vs. face-to-face communication channels such as meetings, InstallFests, and other social activities.

- Which channel is more appropriate for which types of activities or purposes?

Thank the respondent.