Can Local Communities Meet the Governmental ICT Literacy

Policy Goal:

Namibia as a Case Study

Senior Lecturer, Educational Technology, Faculty of Education, University of Namibia, Namibia. Email: pjboer@unam.na

Introduction

In June 2009, students of grades 5 and 6 at the Ngoma Primary School in Namibia's Caprivi Region received 100 XO laptops. The project required local partners and community to focus on the project of integrating technology into the learning environment both in and out of school. The larger goal of this single case study was to investigate whether a local community could meet the government's "ICT in Education" Policy literacy goal. It was hoped that the project would be sustainable and result in a ripple effect where parents and other family members would also become computer literate. Computer literacy in this investigation was defined as the ability to use the Internet for searches and e-mail, and to use a word processing programme and other fundamental computer functionalities. Local engagement consisted of the tribal chief, four student teachers from the Katima Mulilo Campus of the University of Namibia, Itenge Development Fund (IDF, a local community fund), the Salambala Conservancy, Telecom Namibia, the principal of the school, teachers and the students. The project implementation took place over a period of three months, followed by contact sessions with the community for four years.

The study investigates why the project lacked the capacity to expand beyond the boundaries of the school. Furthermore, the interaction between the participants in transferring ownership to the community is analysed. In addition, this study uses Matland's conflict-ambiguity model as a policy instrument to evaluate the "implementation problem" of governmental ICT policies introduced at the local community level.

Background

The Republic of Namibia is a country in Southern Africa on the Atlantic coast. It is bordered by Angola and Zambia to the north, Zimbabwe to the north-east, Botswana to the east, and South Africa to the south. Windhoek is the capital city and the largest urban area, with much of the country being relatively sparsely populated.

The independence of Namibia from apartheid South Africa on the 21st of March 1990 set the country on an ambitious path towards reform of the education system. In 2003, the Namibian government set forth a blue print for their future in the form of "Vision 2030", launched in June of 2004. Vision 2030 lays out plans for improving all the sectors in Namibia, to eradicate the apartheid legacy from society, and to develop the Nation into a knowledge-based economy (Vision 2030, 2004).

The Ministry of Education (MoE) developed the Information, Communication and Technology (ICT) Policy for Education in 2004. This policy was to provide guidance for integrating technology into the classroom, to achieve the National "Vision 2030" goal of a knowledge-based society and economy. In order to bring the ICT Policy for Education to life, the Educational Technology Implementation plan, dubbed "Tech/Na!" (meaning technology is 'good' or 'nice' in 1 Khoe Khoegowab?), was officially launched in September 2006. Namibia considered a multi-stakeholder approach important as it proved valuable in providing more opportunities to raise educational issues and foster "growing importance for local accountability" (Donnelly et.al., 2006, p. 136).

Local Context

Ngoma is located seventy kilometres from Katima Mulilo next to the Botswana border (see figure 1). This settlement is within the Salambala conservancy which consists of a primary school and a high school. Learners at the primary school walk as far as five kilometres from the surrounding villages to attend the school. The community lacks major employment opportunities, and as a result, poverty and alcoholism are widespread. In addition, the school has a feeding program for many orphans and vulnerable children.

Despite having no industry, the community has several projects of which one is the bicycle empowerment network (BEN). BEN aims to make the community more mobile with services that include selling and repairs of bicycles as well bicycle ambulances. A collective craft centre next to the main road is another project, where local women sell their pottery and basket weaving crafts to tourists. The main settlement has electricity and telecommunication cell phone coverage. However, the majority of the surrounding community has limited electricity and no running water in their homes. Water is collected as needed from the nearby boreholes or wells.

ICT Literacy in Local Communities

There are reports with anecdotal information of how One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) has been effective in achieving Information and Communications Technology (ICT) literacy at schools and in communities. Despite these reports, little empirical evidence is available on how local communities respond to government policies or implement government policies with minimal government involvement. Studies criticise government policies as lacking in local or cultural knowledge, and that these policies are in many cases borrowed from other countries (Dolowitz & Marsh, 2002; Philips & Ochs, 2004; Evans & Davies, 1999; Rose, 1991).

Rogers (2003, p. 1) noted that "getting a new idea adopted, even if it has obvious advantages is difficult." Using various case studies to illustrate this point and provide insight as to the complexities and difficulties involved around diffusion campaigns, Rogers (2003) offers insight that diffusion of innovation is a social process more than a technical matter. Through understanding local culture, customs and practices, policies can be created that would allow for easier adoption which would lead to social change in the system (Rogers, 2003, p. 6). Literature about ICT's in rural communities tends to focus on access and uses of these technologies. Herselmman, 2003, highlights various types of drawbacks facing rural schools in particular i.e. basic infrastructure, isolation, resources and bad teachers and poor technology access.

The factors given above play a role in any implementation process, but do not determine success or failure of implementation. Lack of empirical evidence on effective use of technology resources hinders the policy implementation progress. Thus there is a case for taking specific action. Fuhrman, Cohen & Mosher (2007), propose research that investigates policy implementation actions. They put forth a strong case for cumulative ethnographic research on effective policy practice (Fuhrman et.al, 2007). Fuhrman et.al. (2007), further state that for two decades much ethnographic work has been done in the United States, but little of that research is framed so as to inform knowledge for practice and thus is not usable by practitioners. Of importance are the approaches used in the implementation processes of these technology resources.

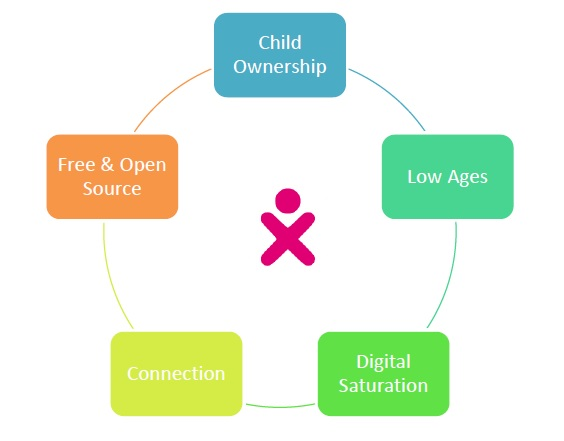

OLPC Principles/Approach

Laptops were donated by OLPC. The One-Laptop-per-Child (OLPC) is a non-profit organization that develops low-cost laptop solutions called XO laptops. The mission of OLPC is to provide educational opportunities for the world's most isolated and poorest children by giving each child a rugged, low-cost, connected laptop. The laptop includes software tools and content designed for collaborative self-empowered learning including the OLPC-wiki (wiki_OLPC, 2014). The project was awarded 100 laptops to donate to a school in Namibia. By nature of the donation, the project had to follow the OLPC five core principles when implementing the technology. The five core OLPC principles are illustrated in figure 2 below.

The five approaches or principles are explained as follows:

- Child Ownership: The ownership of the XO is a basic right, coupled with new duties and responsibilities: including protecting, caring for, and sharing this creative environment.

- Low Ages: The XO is designed for the use of children ages 6 to 12. The size of the laptop is small and inherently, the keyboard is integrated with small keys.

- Digital Saturation in a given population: OLPC is committed to elementary education in developing countries: the whole population to have access to a device.

- Connection: The XO has been designed to provide an engaging wireless network. The laptops automatically connect to other XOs in a radius of approximately 30 meters. This connectivity can be as ubiquitous as a formal or informal learning environment permits.

- Free and Open Source: All children are learners and teachers, and this spirit of collaboration is amplified by free and open source tools. There is no need to depend on external sources in order to customise software into the local language, fix the software to remove bugs, or repurpose the software to fit their needs.

ICT literacy in Local Communities:

Since the deployment of OLPC's laptops in various countries, its five core approaches have resulted in little empirical evidence in terms of effective reach of ICT literacy to communities. Most of the existing evidence with regard to successful ICT literacy as it affects/influences communities is anecdotal. Pringle and David (2002) noted that ICT represents the "greatest tool" for communities who can self-educate and add value to their community. They further note that even if research revolves around models for constructive application or implementations, assessing the impact of these projects is difficult (Pringle & David, 2002).

Other studies have shown that the use of the XO's has been low in a classroom situation due to the lack of pedagogical approaches, or teachers not understanding the value of using technology for teaching and learning (Cristia et.al, 2012, Severin et.al, 2011). However, anecdotal successes have been reported with the ownership component of the OLPC model. Children taking their XO's home has led to parents learning limited computer skills such as typing and more importantly finding information while surfing the internet.

Additionally, there is proof that literacy has improved amongst some of these communities because children have taught parents how to read and write using some of the programs on the XO (Cristia et.al, 2012). Results from a recent study on the implementation of this education technology model in Peru have found a high level of teacher satisfaction and a slight improvements in the students' analytical skills (Severin et.al, 2011). The Severin study indicated that problems occurred with the reluctance to allow the laptops to be used at home. Of the sample size, 43% of the schools did not want to implement this goal (27% thought the laptops would get damaged, 5% thought they would be stolen, 3% were not aware of the element of the program) (Severin et.al, 2011). Despite these mixed outcomes, research continues to focus on finding good practice in delivery of ICT to these rural communities. Moreover, measuring these outcomes based on government policies are of importance as it helps governments and communities measure the impact of several initiatives over time.

Policy Measurement Instruments:

The complexity of implementing any technology policy ranges from the policy instrument used, to barriers for deployment. In this paper two evaluation measurements for policy success were considered. These were McDonnell and Elmore (1987) or the Matland (1995) model or framework. McDonnell and Elmore (1987) present a framework of four generic classes of instruments i.e. mandates, inducements, capacity building and system changing. They describe mandates as rules governing the actions of individuals and agencies which are intended to produce compliance. Inducements, on the other hand, allow for transfers of money to individuals or agencies in return for certain actions. Capacity building is the transfer of money for the purpose of investment in material, intellectual, or human resources. Finally, system changing transfers official authority among individuals and agencies in order to alter the system by which public goods and services are delivered.

When using McDonnell and Elmore (1987) to evaluate the enactment of the Tech/Na! implementation plan, it can be concluded that the Namibian implementation is a system-changing approach. This means that the "authority" of local level initiatives is transferred to the Ministry of Education (MoE). However, elements of capacity building and mandates are built into the technology policy implementation at various levels. Capacity building involves financial cost, where the MoE allocates funds to deploy computers to each of the 1661 Namibian schools (MOE, 2011). Furthermore, these funds provide professional training for teacher educators and student teachers at the University of Namibia. McDonnell and Elmore (1987), go on to suggest empirical evidence that attempts to classify a diverse set of policies, operating in different institutional contexts according to the four instrument types.

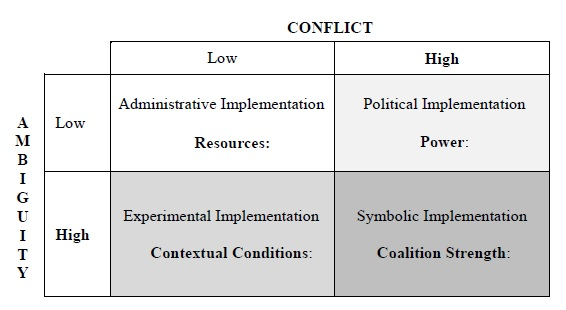

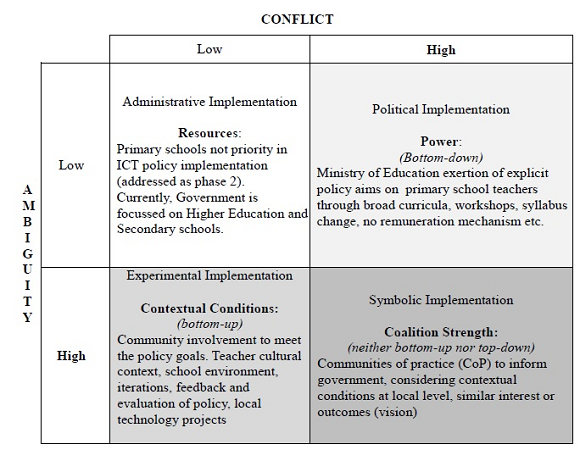

Richard E. Matland (1995) in his article "Synthesizing the implementation literature: the Ambiguity-Conflict Model of Policy Implementation" proposes a four paradigm model (see figure 3). This model consists of low conflict-low ambiguity (administrative implementation), high conflict-low ambiguity (political implementation), high conflict-high ambiguity (symbolic implementation) and low conflict-high ambiguity (experimental implementation). Matland (1995), explains how the success of the policy can be defined within the context of how high or low was the degree of conflict or ambiguity that was negotiated. Investigating any policy implementation involves people. People are the main participants of the realities of coming to grips with the implementing change process (Fullan, 2007). It also involves the "Spirit of the policy" which is the goals, target and tools used to capture the intent of the policy. In addition, the educational and political context in which the policy is to play itself out (Honing, 2007) is of importance.

When conflict is low, the teacher or participant assumes ease at negotiating implementation of the policy aims (Matland, 1995). At a low level of conflict, the teacher's analysis and understanding of the policy aims can be bargained through persuasion, problem solving and coercion (Matland, 1995). When the level of conflict is high, the teacher experiences a level of incompatibility of their values with the policy aims, and teachers struggle to negotiate enactment.

When the ambiguity is low, the actors that are involved are clear as to what their roles are in the implementation process. There is a sense of compliance from all actors involved, however the goals to achieve the policy goals can appear incompatible and the conflict can be that the technology to meet the government initiative is not present. When the ambiguity is high, conflict is lowered in that the policies are more symbolic and confirms new goals by the government. In this instance the introduction of technology into the curriculum and the efforts towards ICT literacy for all citizens is a symbolic act by government and understood and agreed upon by teachers. Despite possible vagueness of the policy and the many interpretations of the various actors concerning the vision; the agency and the willingness of the various actors are of importance in the ambiguity component of the model (see figure 3). Matland, 1995) states that "the central principle is that local level coalition strength determines the outcome" (p.168). Thus, the policy course and direction can be determined by the various actors at the local level and how they control the available resources.

The overall objective for government is to reduce costs and/or spending and increase the sustainability of a successfully implemented policy. This study focuses on whether a community can implement and sustain a policy without government involvement. All educational technology policy implementation studies are aimed at success, effectiveness and sustainability. Matland (1995) defines successful implementation as "statutes that comply with the directives of the statutes" or "where there is an improvement of the political climate around the program". It could be inferred that if the political climate around the program does not improve, success cannot be claimed.

In the early implementation of educational policy, analysts excluded actors such as teachers, principals and learners, because they underestimated and misunderstood their role in policy implementation (Honig, 2007). More current trends in policy studies show that the involvement and understanding of teachers in the process is of utmost importance (Honig, 2007, Stone-Wiske, 2007). Just as the focus on teachers is relevant, the focus on the individual community member as "policy-maker and implementer" should be equally considered. Research that focuses on individuals in a community playing a role as implementers has become a valuable form of research to inform the policy-maker of how to improve the policy.

Teachers and Policy Implementation:

For a policy to be implemented successfully, teachers as well as community members will have to learn about the policy ideas and its objectives. Cohen & Barnes, (1993), propose that by definition new policies contain new ideas or new configurations of old ideas. This implies some acquisition of new ways of thinking and doing. Elmore & McLaughlin, 1988, suggests that local variation in policy implementation is a sign of good policy. Due to its adaptability in meeting the diverse needs of the practitioners in the situation where it is enacted. The interpretation and enactment of policy is influenced by teacher's existing internal and external conditions (Lieberman, 1982; Lipsky, 1980). The question that arises is whether the objective of the policy has been achieved through local adaptation.

Further literature points to the fact that "practitioners" interpret policy through their existing beliefs and their experiences with other policies (McLaughlin, 1987). Practitioners construct different interpretations of policy and it is enacted differently in the classrooms (Judson, 2006). There is very little evidence about what teachers do and how it affects student's learning" in the classroom (Haertel & Means, 2003).

Much of the literature in these sections is focused on policy enactment understanding of teachers. Due to the project being implemented at the school level, it was the expectation that teachers would empower the learners to grasp the importance of integrating ICTs in their everyday life and transfer the importance of ICT literacy for every citizen.

The Implementation of the project

Various actors were involved in the implementation process. Their involvement ranged from a "once-off" to an "active and continuous" involvement. The implementation followed the OLPC approach:

- (Child) Ownership: The ownership model resulted in every grade 5 and 6 learner receiv-ing an XO laptop. In this project, all the ten primary school teachers were given an XO laptop in order to familiarize themselves with the software and operating system. Teachers received technology integration training three times per week for two hours in the afternoons in order to better plan a technology learning experience for the learner using a one-on-one laptop ap-proach. Learners were allowed to take the laptops home and required to bring them back to school within the school week. Exploration sessions of the XO laptops were scheduled for the grade 5 and 6 learners in the afternoons, Mondays to Thursday. Additionally, each of the four student teachers from the Katima Mulilo Campus of the University of Namibia (UNAM), re-ceived an XO and they travelled 70 km four times a week to assist the learners in doing basic ICT literacy in these afternoon sessions.

- Low Ages: The XO laptop being designed for the use of children ages 6 to 12, the project chose grades 5 and 6 in awareness of the the language policyin Namibia, where grades 1 to 3 classes are in mother-tongue instruction. Grade 4 is the transition year from mother-tongue to English.

- Digital Saturation: The Ngoma Primary school had of approximately 500 learners from pre-primary to grade 6. Saturation in the school was not possible as only 100 laptops were donated for the specific school.

- Connection: Through the Itenge Development Fund's (IDF) commitment to pay for Internet connectivity to the school, Telecom Namibia was able to set up a wireless network for internet connectivity. Additionally, a server with Moodle was set up at the school with the idea that teachers would begin to use a blended approach to their teaching with the laptops. Networking further extended to communication amongst learners while at home in their respective homesteads. As mentioned earlier, the laptops automatically connect to other XO's in a radius of approximately 30 meters.

- Free and Open Source: Teachers were made aware of the differences between proprietary and open-source software . Namibia's ICT policies acknowledge both, and choice is left to the schools, based on their budgetary needs. In many cases teachers are only familiar with the Microsoft Office package and struggled with understanding open-source. A few teachers were given the responsibility to "reflash" XO laptops where technical problems occurred such as software bugs, and to re-purpose the software to fit their needs. Again the IDF committed to paying for maintenance and repairs and tp purchasing parts.

Methods

This study used a case study approach selecting one critical case. Purposeful sampling was used to learn from this implementation of OLPC laptops in a community. The interactions experienced between community members as they negotiated the implementation of the project were the primary focus. Participants were chosen for the role they played in the implementation. Four of the ten teachers, and fifteen from the nearly 80 learners who participated, were interviewed. Interviews focussed on the effects of laptop ownership for the learners, integration of technology into the teaching and social life and the influence of the laptop in the learner's home or community life. Additionally, observation data from field notes informed the research. Analyses of interviews were done to reveal agency and show interactions.

Findings

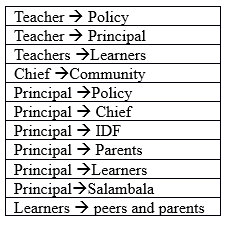

Findings described the relationships between stakeholders and their roles. These interactions between the participants in transferring ownership to the community were analysed. The table below identifies teach role and interaction:

Teacher → Policy:

Interviews with teachers revealed that they were aware of the Ministry of Education's ICT policy. This awareness does not always constitute an understanding of what is to be done and teachers noted that they did not understand what was expected of them. Themes confirmed that for many teachers technology integration was about becoming an expert in learning the computer. Teachers did not show any leaning towards the idea of establishing a "collaborative learning culture" where the children could co-share/teach. They noted that "how can I teach using this technology in the classroom when the children might know more than me?" More training on the laptop resulted in teachers complaining about the time and effort in learning the technology. They also considered learning how to integrate the technology for their teaching as an addition to their already existing full workload. Further concerns from teachers were that the learners were not attending to their homework and that they were just playing on their computers.

In follow-up visits to the project, a computer teacher was hired at the school to teach computer literacy using the XO's but found the open-source operating system and programs hampered her progress with teaching as she was used to a Windows environment. The school revealed that on occasion, PeaceCorps volunteers would visit and demonstrated several technology integration lessons.

Technology integration is understood as the use of the technologies in the classroom for teaching a specific subject and for learner understanding. A one-on-one laptop lesson can range from project-based learning where students are faced with finding a solution to a problem, to simply preparing homework through searching the Internet and typing the assignments, to improving learners' technology and information processing skills.

Principal →Teachers:

The principal along with the teachers welcomed the OLPC program to the school and the community. He was excited at the opportunity that the learners could get access to technology and appreciated efforts for teachers to learn ICT literacy skills and integration approaches. He encouraged the teachers to come for the training sessions in the afternoon. Although he agreed to the OLPC approach, he found the ownership principle difficult to understand. He found the notion of the community owning such expensive equipment absurd. He felt that it was a donation to the school and as such should be locked up in the school strongroom.

Principal →Masubiya Chief:

The principal as the educational leader, decided that the Masubiya tribal chief along with the local "indunas" should do the official handing over of the laptops. He reasoned that this would show support to the project. Under the principal's guidance, appropriate arrangements were made to invite the chief and organize the handing over ceremony.

Chief → Community

At the handing-over ceremony, the Chief issued a stern warning to the community to take care of the laptops. He expressed gratitude and commitment for further financial support through the Itengi Development Fund. The involvement of the chief was minimal and did not extend beyond this function. His involvement however, did appear to be a deterrent for theft as he requested a level of respect from the learners cpncerning their ownership of the laptops and reiterated that because they were the communities' property everyone had a responsibility to protect the laptops from theft.

Principal → Policy:

The principal indicated that he was aware of the Namibian "ICT in education policy" and the "Tech/Na implementation plan".

Principal → IDF Chairperson:

The Itenge Development Fund (IDF) is a community fund that awards scholarships or funding for special projects which uplift the community. The chairperson of the board of trustees, who is also the director of the University of Namibia, Katima Mulilo campus, indicated that he was excited that the learners were going to get an opportunity to be exposed to technology. Through this fund, the principal negotiated monthly financial support for Internet connectivity through Wi-Fi at the school. The chairperson was in agreement with the principal that the laptops should be kept in the school strong room. They raised concerns concerning theft and damage.

Principal → Parents:

During the initial phases of the project the principal agreed to the ownership approach and allowed learners to carry the XO's home. Parents were initially excited and saw the potential of the children owning a laptop as a learning tool which would give them a chance to rise above their current living conditions. Like most parents everywhere, these parents also saw education for their children as a means to a better life. After two weeks of ownership however, the parents complained to the principal that the children were no longer doing their chores of collecting firewood, fetching water and raking the family's homestead courtyards. Further complaints included that the kids would visit the local bars for hours, charging their laptops and recording music played in the bar. Moreover, girls would visit the bars until late in order to record the soap-opera being televised on a local channel.

Additionally, the parents complained that if the children do stay at home they would make noise by playing their recorded music at top volume in the otherwise quiet courtyards. The principal made a decision that laptops should only be distributed for the afternoon program and were to be kept at school. He further justified this decision by stating that the laptops should be kept charged which meant that they would be kept in the school since most learners did not have electricity at home. Complaints from parents appear to point to a lack of understanding in how to balance issues of chores, homework and leisure.

Principal → Learners:

In interviews and conversations with the principal, learners were encouraged to "make use of this opportunity". The principal also noted that the learners were not capable of taking care of the laptops and that he was reluctant to agree to the ownership model which OLPC recommended.

Principal → The Salambala Conservancy:

The conservancy in which the community lives, was interested in using the XO laptops to train conservation officers in computer literacy. Similar to the service Kiosk models in India, the conservancy group were looking to use the Internet services after school for their proposed ICT literacy component. Negotiating with the principal on collaboration proved to be complicated and no agreement could be reached on evening access and supervision as the principals and teachers wanted to lock up after school closing at 5 pm.

Learners → Peers and parents:

Learner Views on Agency:

Learner views did not show much insight into their own agency in the project. They all noted that they enjoyed taking the XO home and playing games, writing in the word processing programme, but mostly they enjoyed the video recorder and digital camera function of the laptop. The majority of the learners noted that their involvement with parents, siblings and other extended family were only to take digital photographs and video record them. A few mentioned that they showed their younger siblings how to open and explore the keyboard in the word processing program. For the most part, the learners noted that the experiences were only shared amongst their peers. From the interviews eight learners indicated that their parents asked and showed interest, but they only had minimal engagement. Six indicated that their parents did not show any interest while one learner noted that parental involvement "was a disturbance" because the parent was trying to learn and explore the laptop.

All students noted that "SPEAK", a computer program that assists in playing back text phonetically was most useful in that it improved their English reading and pronunciation in speaking English.

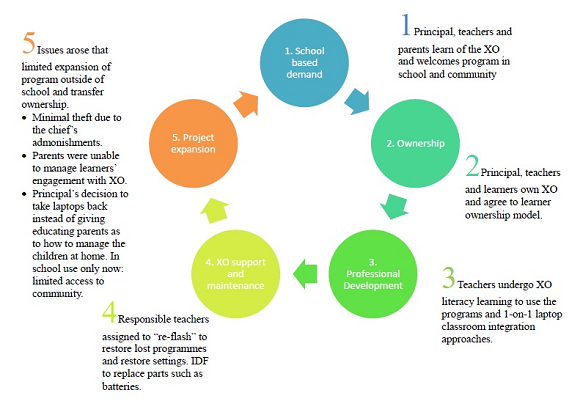

Figure 4, below summarizes the process and the major issues arising from the study.

Discussion

The study focused on the lack of ability of the project to expand beyond the boundaries of the school. The interaction between the participants in transferring ownership to the community was found to be mostly "one-directional" with unclear communication and understandings of the larger ICT literacy goal. From the findings, it appears that the Namibian ICT in education goal towards ICT literacy was not clearly communicated to the principal, and in turn to the teachers, learners, and the community. As such the importance of working towards this goal was not understood.

Spillane & Jennings (1997); and Coburn, (2005), link the implementation of technology integration to the delivery of the technology policy by government. How the technology policy is presented to the teachers by the principal or to the principal, affects the initial experience and understanding of the policy. The way teachers learn and treat the ideas of the policy shows what they value (Spillane & Jennings, 1997). It was crucial in this project that the teachers understood the policy and the larger goals, as teachers were instrumental in conveying these important issues to the learners. Further investigation on how the government presented this policy to the principal, to the teachers and the community is needed. Additional investigation should be around the relationship between the learners, ownership model and the community.

The fact that the community is situated in a nature conservancy appears important. In a nature conservancy the land users are expected to manage their activities in an environmentally friendly manner without changing the land use. Thus, there is a voluntary agreement between the Government declared national park and the people that live within these areas. There is a common understanding that the area is to be co-managed by the community and the government to protect the fauna and flora species residing there. Even though this paper did not explore how government policies such as issuing permits for collecting firewood and hunting permits are received by the community, an investigation of relations between the Government and community is warranted.

The findings did not reveal that the actors transferred the co-management principles to the ICT literacy project. How the community experiences policy implementation and understanding at this level impacts how they would understand education ICT policy. Bailur (2007) identifies several complexities in community participation ICT development projects. He identifies issues of participation being "top-down" and the "insiders learning what the outsiders want to hear" (Bailur, 2007). Gurstein (2007), notes that utilization of ICTs in the community has proven successful when communities do it at their own pace within their understanding of their culture and decision making processes.

A need for communities to inform governments and to push for a more bottom-up ICT development model is important (Gurstein, 2007). Matland (1995), explains that if there is a high level of ambiguity and a low level of conflict (experimental implementation /bottom-up), "outcomes will depend largely on which actors are active and most involved. The central principle driving this type of implementation is that contextual conditions dominate the processs. "Outcomes depend heavily on the resources and actors present in the micro-implementing environment" (Matland, 1995, p.165/166). At present the government of the Republic of Namibia has placed Higher Education and Secondary schools as priorities and allotted resources such as training, computers and technical readiness for the implementing of the ICT in education policy. Primary schools are identified as secondary thus, no deployment of the ICTs is present at the Primary school level. Matland (1995), identifies this kind of implementation as "Administrative" with low conflict and low ambiguity and largely top-down.

The ownership model and conclusions

The OLPC approach to ownership appears to recognize the link between the learners and the community. The results further indicate that the ownership model appears to have been misunderstood by principals, teachers, and parents. In this project we cannot report what the effects of ownership would have been on the community. It would be of interest in further investigations to note whether results would be markedly different if the study followed the same or similar project implementation where the ownership model was adhered to.

Despite the fact that no resources are allocated as priority to primary schools, government continues to exert "power" through being explicit about its ICT literacy goals in the broad curricula and appending instructional policies to all teachers. Matland (1995), suggests that the ideal situation should be "neither bottom-up nor top-down" where "coalition strength" is exerted from both community and government alike. In this high conflict level, high ambiguity level, both community and government find ways to congregate around the same vision. Communities inform government and the contextual conditions at local level are considered. The figure below, (fig 5), presents the possible scenarios of outcomes and indicators for each of the levels from this OLPC project.

This case study highlights the importance of more research in communities meeting governmental policies. Further investigation is warranted on the approaches and ways in which the communities can be "empowered" to inform government on how to achieve the common interests and vision.

Footnotes

1Khoe Khoegowab is a non-Bantu language that contain "click" sounds. It is spoken in Southern Africa and have been loosely classified as Khoisan languages.

References