Embedding Digital Advantage: A Five-Stage Maturity Model for Digital Communities

Democratise

London, UK

Email: andy@democrati.se

Author's Note

I was asked by the Editors to republish this paper in JoCI ten years after its original publication because, though some of the language and context is now dated, the underlying concept and model seem not only relevant but significant today. Michael Gurstein recently wrote about his own problems with the concept of the 'digital divide' and I agree. (Gurstein, M. (2015). Why I'm Giving Up on the Digital Divide https://gurstein.wordpress.com/2015/04/15/why-im-giving-up-on-the-digital-divide/)

If one takes the UK (where I am now based, though this paper is based primarily on New Zealand data), access to the internet has remained fairly consistent at around 85% for a number of years (depending on the source). More importantly, the (about) 15% who aren't online, equally don't want to be, can't afford to be or can't get access. There is a lot of research on this 15%. What is understood less well, particularly in policy circles, is what the remaining 85% looks like. The simple quantitative focus on those that do or don't have access has led to a dearth of policy and research on "effective use" (Gurstein 2015) and the range of skills and abilities of those that are online. Clearly this is a continuum from expert to barely functioning, so to suggest that we have a digital nation simply because 85% of the population has internet access is naïve and dangerous. To design policy and develop public service based on this assumption is self-evidently problematic. Simply put: access is not equal to effective use. And this matters for both policy and practice.

I find it much more productive for us to position the network as a core public-asset infrastructure, to establish a right to access and then to focus on effective use once people are connected in terms of digital literacy etc. My friend and colleague, Aldo de Moor, in the ensuing conversation on the Community Informatics Research email list suggested the need for "usable monitoring and evaluation-frameworks and standards that capture the essence of socio-technical effective use-aspects", he wants us to avoid these frameworks becoming "statistical straightjackets". I agree, and republishing this paper is a modest initial contribution to that. Please read it in context: it was written in 2004, in a country on the edge of the world, before the onslaught of social media, when digital access was far less ubiquitous and mobile coverage limited and expensive. Yes, we have come a long way so that access, particularly mobile, is more ubiquitous and social and digital media are normative for many of us. But what hasn't changed, and what this paper offers, is the underlying requirement for us to critically understand effective use.

The original version of this paper was first published at the Australian Electronic Governance Conference. Centre for Public Policy, University of Melbourne, 2004.

INTRODUCTION

Observers such as Putnam (2000) note that engagement in traditional community activities has been declining since the 1960s. This decline is mirrored in the political realm, however Coleman and Gøtze (2002) see this drift away from participation as having more to do with apathy brought about by the increasing technocracy and perceived distance of governments, rather than apathy for democracy itself. There is a discourse within New Zealand (including government) promoting increased participation in the processes of local government, yet the reality here as elsewhere is that participation in the democratic life of the nation is falling.

The Quality of Life Survey carried out by the Councils of New Zealand's eight largest cities reports low levels of satisfaction with the level of public involvement in the local decision making process, ranging from a high of 42% satisfaction in Dunedin to lows of 32% in Auckland and 30% in Manukau (Anonymous, 2003). News media have long been considered a bridge between the public (and public opinion) and government, yet New Zealand today offers little more than 'an uneasy compromise between quality and popular news discourses - that represents the worst of both worlds' (Atkinson, 2001, p.317). This reduction in diversity has occurred alongside a dramatic increase in the management of news, leaving only limited opportunities for citizens to express their own views (Gustafson, 2001).

It is suggested that Information and Communications Technologies (ICT) offer the potential to dramatically change the processes of government and the interactions between government and citizens (Coleman & Gøtze, 2002; Mälkiä, Anttiroiko, & Savolainen, 2004). The potential for citizens to successfully harness new and emerging technologies to influence the democratic process has already been seen in the role that text messaging played in coordinating and propagating the 2001 campaign to depose the President of the Philippines (Rheingold, 2002). Can the sophisticated application of networked technologies and online communities arrest or reverse the decline in participation and representation? Whilst the answer appears to be a cautious 'yes' (Coleman & Gøtze, 2002; Mälkiä et al., 2004), ICT is not ubiquitous; many citizens are yet to acquire the skills needed, firstly, to become effective users of ICT and, secondly, to become producers of information, news and knowledge. This paper will discuss the background to the use of ICT within community settings, highlighting opportunities and constraints. By doing this it will contextualise the issues that communities face in becoming ICT-enabled and will then present a five stage model, contextualised within a community development framework, that can be used to both support the emergence of connected communities and to measure the levels of ICT maturity within a community.

MOVING COMMUNITIES ONLINE

As Day (2004) observes, defining community can be complex and problematic in an emerging and cross-sectoral field of study. For the purposes of this paper, a simplistic definition is used whereby a community is considered to be a group of individuals with a shared interest (whether topical or geographical). Extending this definition, a 'virtual community' enabled through ICT, is:

A social aggregation that emerges from the [internet] when enough people carry on public discussions, with sufficient human feeling, to form webs of personal relationships in cyberspace (Rheingold, 1994, p.5).

As already discussed, engagement in traditional community activities has been declining since the 1960s and with it social capital - the resources that communities have available for support, trust, obligation and reciprocity - has fallen as well (Putnam, 2000).

It has been recognised for over forty years that information and communication are at the core of human understanding of social and political action and the rapid development of new technology-based tools of knowledge generation and information processing have major implications; where society is exposed to such technology it is being fundamentally changed (Ellul, 1964; Habermas, 1979, 1987a, 1987b; Hall, 2000). Whilst technology does not of itself determine social process it can be seen as 'a mediating factor in the complex matrix of interaction between social structures, social actors and their socially constructed tools' (Castells, 1999, p.1). The relatively un-regulated and anarchic nature of the internet creates a virtual space that offers the potential to develop social movements and be developed in ways that are appropriate to the needs of such movements. As Bollier (2002) observes, the internet is an effective tool for the establishment of public commons, citing examples such as the Open Source movement to demonstrate the potential for citizens to establish themselves online relatively easily and cheaply.

In order to develop an internet based environment that supports grass-roots change, it is necessary to encompass the development of localised solutions, where the experiences and aspirations of the community can be harnessed to create an environment of empowerment and learning. Literacy is a critical element in individual and community empowerment (Freire, 1972, 1974) and, as Okri (1997, p.60) observes, writing is itself a form of resistance, arguing 'writers are dangerous when they tell the truth. Writers are also dangerous when they tell lies.' Language and culture are key elements and the online environment is immersed in the culture of the community that it serves (Castells, 1999). The internet has the potential to build bonds that transcend the virtual and develop in the physical world. Castells (1999) argues that sociability on the internet is both weak and strong, depending on the people, content and relationships. He argues that the electronic world does not exist in a vacuum and that it requires some reference to the physical and social worlds of its participants. Although Glogoff (2001), Rheingold (1994) and Castells (1999) observe that the internet can enhance community by removing boundaries of space and time, Glogoff cautions that communication richness is directly related to the richness of the medium. Online communication is not as rich as face-to-face communication, nor is it as personal, trusting or friendly.

Despite the liberating potential of ICT, dominant hegemonies persist and Castells (1999) sees traditional sources of exclusion being duplicated online. Attempts are being made to control the flow of information such that 'the internet is in danger of becoming yet another instrument of cultural and political hegemony' (Ni hEilidhe, 1998, p.1). Despite (or perhaps because) the internet is already the largest public commons, serious attempts are being made to manage, control and own both the networks and the flow of information (Bollier, 2002). The elevation of both the individual and of the free-market have left in their wake an underclass that does not have the opportunities, knowledge or access to resources (ALICE, 1998). Goslee (1998) discusses the affordability of access to ICT and particularly the internet in low-income urban and rural communities in the US, concluding that new technologies are in fact aggravating the divide between rich and poor. Hall (2000) agrees, observing that deprivation of access to ICT results in a failure to become technologically literate, which is a key factor for success in an Information Society. Those who are already marginalized are becoming even more so because they are unable to access the new technologies available to wealthier communities (Goslee, 1998).

In New Zealand, there is a strong correlation between income and access to ICT. The urban poor, those living in rural locations or the elderly are more likely to lack internet access at home (Craig, 2003). For example, 50% of those owning their own home have internet access as opposed to only 11% of those living in state or local authority rental housing (Statistics New Zealand, 2002).

EFFECTIVE USE

The hegemonic structures which support the integration of ICT into community life are, however, being challenged by minority cultures. The effective use of ICT, which Gurstein (2003, p.9) defines as 'the capacity and opportunity to successfully integrate ICT into the accomplishment of self or collaboratively identified goals', is critical but the determinants of effectiveness need to be cultural and political, not only technological (Mälkiä et al., 2004). There are three examples of the effectiveness of ICT as a tool to challenge formal organisational and hegemonic structures. The first example is the use of the internet by the activist community of technologically literate participants promoting and supporting environmental activism. White (1999) observes that the environmental movement was one of the first to use the internet as a medium for activism and that the success of campaigns in this medium have been partly due to the low cost involved. The internet demonstrates potential to be utilised as a counter-hegemonic and overtly political tool. The second example, the role played by new technologies in fostering the rising tide of anti-globalisation protests, was the subject of a report from the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (Canadian Security Intelligence Service, 2000, p.5), who reviewed the impact and logistics of demonstrations at international summits. They observed that both the internet and mobile phones were key tools in the organisation of such actions. The report described the internet as 'creating the foundation for dramatic change' and was being used to plan, communicate and manage logistics:

The internet has breathed new life into the anarchist philosophy, permitting communication and coordination without the need for a central source of command, and facilitating coordinated actions with minimal resources and bureaucracy (Canadian Security Intelligence Service, 2000, p.5).

Where the internet allows hegemonies to be directly challenged it is at the frontier of where social norms can be subverted. Wakeford (2000) describes how a 'cyberqueer' culture successfully inhabits cyberspace, subverting and challenging the norms of heterosexuality, utilising newsgroups, chat rooms, websites and email. The internet is used as both a support network and as a tool for proactively establishing a queer identity that challenges stereotypical views of sexuality and sexual orientation and which is itself a direct mirror of physical-world queer culture (Woodland, 2000). This demonstrates a fundamental requirement in the establishment of any community, namely the creation of a safe place, similar to the 'third space' envisioned by Oldenburg (1991) and which Rheingold (1994) adopts to describe virtual communities, seeing them as distinct from work or home and characterised by a regular clientele. In cyberqueer culture, as Woodland (2000, p.418) observes, such communities combine the 'connected sociality of the public space with the anonymity of the closet' and hence the internet presents the individual with the opportunity to transform the tension between private and public, emerging from a 'shameful secret to a public affirmation' in a safe and supportive environment.

ELECTRONIC DEMOCRACY

ICT is allowing citizens to reclaim their voices at a time when there is ever-increasing decentralisation of decision making away from elected representatives towards 'experts'. In this new technocracy, decisions are based on science and professional knowledge, not public opinion (Mälkiä et al., 2004).

The discussion so far has shown that the internet is a powerful tool for connecting people with information. ICT is valuable when harnessed (like other media) for communicating a message, however, it also extends the traditional concepts of media into an interactive experience, where the views of many can be expressed and potentially disseminated widely. It is this potential that sets ICT apart from traditional print and electronic media and which offers great potential for citizens to become more involved in the political and democratic processes. As Schuler (2000) argues, ICT provides tools for strong democracy, such as email, forums and online access to documents. Organisations such as Minnesota e-Democracy (www.e-democracy.org) and the Waitakere eDemocracy Group (www.wedg.org.nz) demonstrate the potential for citizen-led engagement. Examples of top-down, government led, initiatives include Brisbane City Council, Camden Council (UK) and Rutland County Council (UK) (online fora), the Queensland and Scottish Parliaments (e-Petitions) and Estonia, Queensland and Camden Council (broadcasting of legislature and executive). In 2002 Ronneby (Sweden) created an eDemocracy website and discussion forum with the intent of increasing interest in the upcoming municipal election. Council candidates were able to present their views and the public enter into online discussions. An evaluation of the project rated it as a successful pilot and well received by citizens, however, it was not successful in increasing voter turnout (Ronneby Kommun, 2002).

Whilst the rhetoric of government values engaged citizens and governments feel the need to solicit 'feedback in order to develop good policy and services at all levels' (Office of the e-Envoy, 2001, p.1), citizen involvement should not be assumed. Ranerup (2000) observes that, whilst on-line fora can be initiated by governments, the community or other active stakeholders (such as researchers), her own experience of Swedish local government was that citizens, whilst seen as participants in a forum, were not necessarily consulted over its establishment and design. This highlights a gap between the technocracy of public administration and the desire of those citizens interested in democratisation and the revival of representative bodies (Chadwick, 2003).

Although most developed countries have an eGovernment strategy, there is no clear articulation of the link between the often-stated efficiencies gained in the delivery of government services and strong democracy (Coleman & Gøtze, 2002). There is a discourse within governments that sees eGovernment as a tool for the management and delivery of services from the centre out. The New Zealand e-Government Unit observes that 'new technologies will enable easier access to government information and processes. People will be better informed and better able to participate' (2003, p.1). Unfortunately, the strategy for achieving this identifies only three limited objectives:

- Make government information easier to find.

- Publish key government information online.

- Provide multiple channels for contact with government.

FIVE STAGE MODEL

eDemocracy, Chadwick (2003) suggests, is about scale, rendering convenient access to participation beyond traditional constraints of space and time. ICT must become ubiquitous for eDemocracy to be effective and barriers to ubiquity can be technical, economic, cultural, social or political. Where local communities can become effective users of ICT and become active producers of their own content, it is demonstrably possible to affect change and influence local political decision making (Williamson, 2003). The challenge for policy makers and practitioners alike is that many communities do not have equitable access to ICT, not all citizens are ICT literate and many communities and interest groups lack the knowledge and skills to be effective users.

The model presented here offers a simple evolutionary framework that can be used to identify issues, maturity and progress of ICT in a community or group of communities and act as input into the development of policy and localised models for community ICT. The initial model draws on literature which includes Patterson's (1997) four interconnected nodes (design, access, critical mass and impact) and O'Neil's (2002) meta-analysis of community ICT studies, which reveals five key areas of research: strong democracy, social capital, individual empowerment, sense of community and economic development opportunities. Practical experience that has led to this initial model includes discussions held on the Waitakere eDemocracy Group Discussion list and within the Waitakere City Council EcoTech Working Party. This draft model is strengthened by drawing on the evolving New Zealand National Information Strategy (Library and Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa, 2002). Although the LIANZA model is developed locally it is in part derived from UK models for library and information strategy. It has three core levels:

- Knowledge Access/Te kete tuätea (Infrastructure)

- Knowledge Resources/Te kete aronui (Content)

- Knowledge Equity/Te kete tuauri (Empowered access to information) (Library and Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa, 2002, p.8)

This then extends to encompass issues of continuity and collaboration. The LIANZA model appears to be information-centric, rather than community or people centric.

Phased Maturity

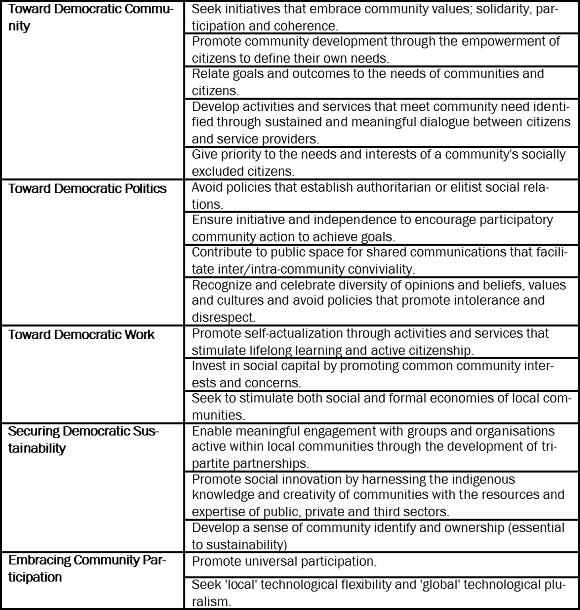

Information technology does not exist within a vacuum. Its use in community settings is influenced by the nature and extent of that community. Day (2004) identifies three components of community informatics as policy, partnerships and practice (3Ps). He then goes on to underpin these macro components with a framework for the democratic design of community ICT initiatives, which asserts that communities need to be empowered before they can campaign for their own interests and influence community policy. The framework aims to create a 'democratic community planning agenda' (Day, 2004, p.33) by defining the critical criteria for successful and sustainable community ICT projects:

The five stage model presented in this paper will be aligned with this framework to demonstrate how it can potentially be used to achieve a sustainable community-based ICT solution. Just as Day has grounded his framework in the 3Ps of Community ICT, the model proposed in this paper can also be related to policy, partnerships and practice: Because access and literacy are societal issues, they must be addressed at a macro or policy level. Partnership allows active communities to work together in either formal or informal ways. They can be used to realize economies of scale, bring on board funding or to provide specialist skills or training that would otherwise not be available to the community. Within the community, projects require ICT visionaries to lead the practice-side of a project and skills development initiatives to ensure that, once projects become established and operationalized, localised resource exists to sustain them (Williamson, 2003).

Adoption of Technology

Zhu, Taylor, Marshall and Dekkers (2003) observe that, in considering the adoption of ICT, it is important to consider the micro-level motivators, both societal and personal. They suggest that individuals need to first be aware of and then motivated to want to use ICT and, subsequently, that it is important that individuals and groups are able to identify value in its ongoing use. As Moore (1999) suggests, adoption is based on an individual's perception of the value and attributes of technology and the discontinuity of change caused by ICT adoption can itself act as barrier to uptake and ubiquity.

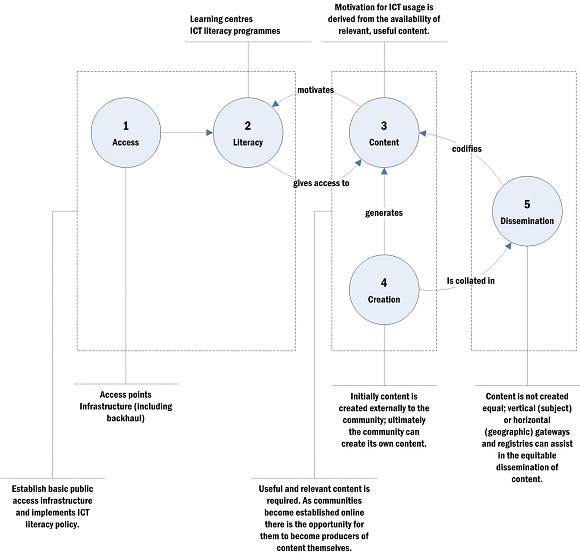

This temporal model identifies five stages of maturity for the use of ICT within communities and can be used as both an assessment tool (for current maturity) and as a planning or policy development tool. Each of the five stages recognises an increasing maturity and sophistication in ICT usage, however, the model should not be seen as linear; the target is not to reach stage five, rather that technology is being applied in a way that is seen as appropriate to the community in question at a point in time (either present or future).

Stages one through four occur within communities. They are not necessarily formal and are not entirely dependent on each other. The requirements and relative importance (or even existence) of a stage is related to the maturity of ICT usage. In other words each of the four stages, whilst to some degree reliant on its predecessor, does not require that prior stages are or were formalised or even articulated (there is likely to be a continuum between a laissez-faire approach and formal strategy or policy initiatives):

Stage 1 - Access

It is not lack of access which causes the digital divide but the consequences of that lack of connection (Castells, 2001) and hence strategies are required to ensure equity of access and opportunity. Citizens must have basic access to ICT. This could be through private ownership, community ownership or privately owned access points. Stage 1 can be sub-classified in terms of the nature, cost and availability of access.

Stage 2 - Literacy

It is not enough that we simply provide community-based ICT resources. It is imperative that those in the community whom the technology is intended to benefit are trained to make effective use of it. As the generation of knowledge supersedes physical production in the post-industrial age, literacy can be judged at two levels: that of basic literacy and literacy in ICT.

Stages 1 and 2 are not necessarily formal; if access and literacy are already present or if no policy/strategy addresses them they could be adhoc, however, this requires individual motivation. Formal strategies are more likely to be needed where other socio-economic factors restrict opportunities for access.

Stage 3 - Content

For ICT to be useful and for communities to be motivated to use it, material and services must be available online that are of a perceived value to the community. Communities must be aware of such information and services and have access to them.

Stage 4 - Creation

Communities have the knowledge, skills and facilities necessary to produce and publish information themselves and to re-package or highlight information that is directly pertinent to them. Logically, stage 4 must have occurred elsewhere to provide usable and useful material for communities entering stage 3.

Stage 5 - Dissemination

The final stage, stage five, is a meta-stage, occurring beyond individual community boundaries. As communities become publishers of new knowledge society risks becoming overwhelmed with information. At present there is also a reality that some information is more readily available and accessible than others (because the producer is more widely known or because of search engine bias). In a truly participative model for Community ICT, processes need to exist to ensure the fair and equitable dissemination of information (that is being received at stage 3 and created at stage 4). Examples of such models might be portals or more likely would involve meta-data, meta-indexes and registries.

Stage 5 becomes viable and appropriate once critical mass has been reached at Stage 4. Dissemination can then take place via fora that are geographical (by city, region, country etc) or topical (democracy, environment, social services etc). At this level, a clearly defined taxonomy is vital and the use of standards for metadata becomes important (Surman, 2002).

Strategic Implications

For the model to be successful, it is important to recognize that ICT is a tool that operates within a wider societal framework. It is important to connect the stages of this model to the wider socio-economic and democratic context of the community in which it is being developed. A simple way to do this is to link the operationalized five stage model described here with Day's (2004) three component parts of community ICT: Policy, partnerships and practice. By way of an example, the 'access' component of the five stage model can be related as follows:

Policy

Local government affirms that ICT is a basic life skill and commits to citizens having access to ICT within, for example, a 2km radius of their home. This is implemented as an information access strategy that places Internet-enabled computers in local libraries, council offices and even subsidises the use of commercial cyber-cafes. Other examples of policy driven initiatives could include telecentres, designed to provide alternative workspaces and reduce road congestion.

Partnerships

Hosts are required for sites; obvious partners are council and libraries. However, at this level the project has no community buy-in or ownership so the concept can be extended to include local community groups that already use the facilities. Partnerships become more significant as maturity increases.

Practice

If the technology is supported by the host, then little is required at this level; the technology could be passive and available for passive users. However, it is likely that more effective use could be achieved if local community members become proactive, perhaps creating groups, such as for senior citizens (where the peer-support can be used to break down technology barriers).

Viewed from the perspective of each stage within the five-stage model, the importance of the macro view becomes obvious:

Access and literacy

Driven by policy and potentially funded as a result, however, this often requires partnerships to acquire external expertise; localized delivery is an important success factor, meaning that community-based practitioners are required to actualize the policy. As already suggested, access and literacy strategies are important for disadvantaged or marginalized communities.

Content and creation of content

Partnerships can provide technology, skills and opportunity (such as community-based hosting projects); local practitioners are required to drive the creation of content.

Collation and dissemination of like resources

As communities reach maturity in terms of ICT usage, partnerships become vital to ensure equitable distribution and recognition of local content. Projects such as geographic portals can be beyond the resource capability of a single community and hence the availability of external funding partners can become a critical success factor at this stage.

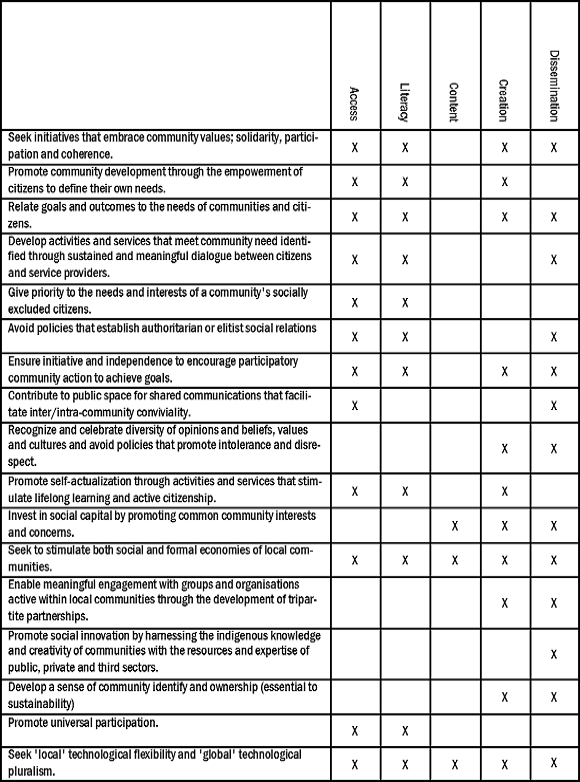

Validating the Democratic Potential of the Model

Day's framework for the democratic design of community ICT initiatives (see Table 1 above) describes 17 generic criteria. Table 2 (below) relates and aligns each of these criteria to a phase or phases within the five stage model. This demonstrates the potential of the five stage model to relate at both a strategic or policy level and at an operational level, where it can be used to address the direct concerns raised by Day (2004). In terms of evaluating the success of a community ICT model, it is possible to link the criteria within Day's framework to the five stages, thereby providing a reference point for both maturity and success from a community perspective.

Summary

The five stages (access, literacy, content, creation and dissemination) are temporal and non-static. Community A can be a newcomer to ICT, getting up to speed with computers in a new learning centre. However, they require content to make the technology useful, this is potentially delivered by others locally or elsewhere who are already creating content. At some point, some members of Community A become both literate and motivated enough to publish their own information: Stories, histories and news. Once enough vertical or horizontal communities have become publishers, it becomes viable to offer a collated dissemination service, by way of a portal or gateway or through online registries.

CONCLUSION

ICT has the potential to transform citizens' engagement with government and thereby develop an eDemocracy culture. Such a culture is essential to the development of new forms of community. Local governments, due to their immediate connection to communities, are the most logical starting points for such developments. The relative low-cost and increasing ubiquity means that communities can publish their own stories and create citizen-led initiatives to influence and interface with governments. However, this does not become truly democratic until the barriers to ICT ubiquity have been overcome. This requires policy to promote ICT literacy as a life skill and ensure that access is available to all who want it. No two communities are alike and the model presented in this paper can act as a road map, assisting communities to identify their own path to becoming effective users of ICT and for measuring the effectiveness of community ICT projects. Equally this model can inform policy makers in terms of recognizing the critical phases of ICT maturity within a community.