Engaging Academia: Strengthening the Link Between Community and Technology

Professor, Civic Intelligence, Evergreen State College, Washington, USA. Email: douglas@publicsphereproject.org

This paper develops the case that academia needs to change in several ways if it is to be socially relevant in relation to communities and the ongoing development and deployment of new information and communication technology. It also explores ways in which academia can move in these directions, specifically (1) ways to integrate community more profoundly into the enterprise; and (2) using the perspective of civic intelligence to orient and promote coherence and coordination. "Socially relevant" in general means that the research helps to encourage information and communication systems that support human development, social learning, collaborative problem-solving and self-governance. An important aspect of this work also includes transparency and oversight in relation to the development of these systems as well as substantial input into their development. Moreover, because the build-out of these systems has such profound implications of surveillance and control, the early warning function is particularly critical. This is an exploratory paper that is intended to be used to advance ideas and further discussion. It is primarily addressed to the academic community that is focused on the use of new information technology in the social lives of "ordinary" citizens.

HISTORICAL OPPORTUNITY

There is a vast race in progress. Unfortunately it is more-or-less invisible. Each day the computer and media behemoths (and those who are beholden to them) strive to shape information and communication systems in critical ways to best suit their objectives. One of these ways, historically unprecedented on this scale, is the wholesale capture of our personal information for their use. Another, of course, is the staggering amount of data being swept up by the intelligence agencies of the United States (and, presumably other countries; not to mention criminal enterprises.) At the same time, the potential power of new ICT to support public problem-solving seems to be increasingly unattainable yet essential. This is critical at a time when many of the economic and political elites of the world are unable or unwilling to effectively and equitably address the problems that degrade lives of people worldwide. As Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann stated, "Special problems arise as a result of differential rates of change of institutions and subuniverses" (1966). This is particularly true in regard to cyberspace: technology doesn't stand still waiting for its reasoned and critical consideration to catch up. Habermas (1996) states that the "public sphere" needs to serve as a "warning system" that must "not only detect and identify problems but also convincingly and influentially thematize them, furnish them with possible solutions, and dramatize them...". While many of our traditional problems - inequality, oppression and war, for example - show remarkable durability, new problems such as mass surveillance, biological warfare, climate change, and complex, interlinked, and incomprehensible financial systems are now part of the portfolio.

We raise the question of how the norms and practices in academia could be transformed in ways that would make academia more relevant in shaping information and communications to empower citizens and communities with public problem solving capabilities (see, e.g. Briggs, 2008). At the same time it is possible and necessary for research to be both rigorous and vital. There is a historical opportunity - and need - to integrate theory and practice more deeply, to renegotiate the interrelationships between research and action, to increase the relevance and influence of the academy for social good. This will mean interrogating and reinventing to some degree the "purpose" of the academy - why it does what it does. It will also require a reinvention of many of the approaches we adopt in our academic and intellectual work.

It should be made clear at the onset that this critique is not intended to suggest that everything the academy does is wrong or that the ideas here have never been raised or, moreover, are currently in use. The critique of the academy as often being not relevant to people's lives or being unable to engage productively with social change movements is, of course, not new. Participatory action research (Whyte, 1991), which has its roots in the 1940s, was introduced as an antidote to these issues. PAR sought to integrate research and action, working with people through participation and inquiry to study the world, change it, and reflect upon the work. The development of participatory design (Schuler & Namioka, 1993) also follows this basic perspective. PD was pioneered largely in the Scandinavian countries (Ehn 1988; Nygaard, 1983) as a way to empower organized labor in the face of impending information technology use. PD is focused on engaging a wide range of stakeholders, including primarily the people who will be the ultimate users of the systems, in the design of the systems.

The argument here is not that critiques of the academy are without precedent. Prior critiques, along with the participatory approaches discussed above, are all valid to this discussion. The difference in the rationale described here is one of diminishing relevance particularly in relation to the civic intelligence of communities, civil society, and, broadly, the non-elites of the world (Schuler, 2001). The recommendations here are for more abiding relationships between the academy and communities, increasing attention to community problem-solving approaches, and generally more and better coordinated work in this area. Transdisciplinarity (Stokols, 2012) and collaboration are also key.

The civic intelligence of the world's citizens needs to be improved (and it can't be mined or harvested) so that they can play more productive roles in addressing the problems we all face both locally and globally (De Cindio & Schuler, 2012). Engaging the community is necessary not only because of responsibility and social debt. Whether this is acknowledged or not, discursive arenas such as the biannual Communities and Technology conference are among the best situated for this type of work. The challenges are great. From large historical, cultural forces to departmental politics and personal biases, we need to re-evaluate the historic opportunities and challenges of the academy in relation to the needs of the world at large.

REINVENTING RESEARCH

The assertions below are directed primarily towards the educational / research sector although I'd like to think they would be relevant to other sectors including business and, particularly, government. The relevant academic communities, at the very least, include the social science community - as well as computer science and other design-oriented communities.

The social processes, behaviors, and other phenomena in relation to information and communication technology may be changing too quickly for meaningful intervention on the part of academia and civil society. If this is true, then their work is likely to become ever more irrelevant over time. As Langdon Winner (1986) pointed out decades ago, "Because choices tend to become strongly fixed in material equipment, economic investment, and social habit, the original flexibility vanishes for all practical purposes once the initial commitments are made." If this is true, Facebook could become the exemplar for social networking although academics and community members - and society at large - may have critical needs for other systems - deliberative ones, for example; or ones that don't use personal information for private profit. However, because this work may not be immediately measurable or does not have an adequate funding stream it may be passed over for academic attention.

The argument is often made that the market will provide society with what is needed. (A variant says that the profit-oriented computer platforms, applications, and services only provide people with what they want.) This is a risky and unproven argument especially in the context of the quickly changing ICT environment (including policy). The argument, scarcely hidden, is that democracy can be reduced tout court to economic forces, often abbreviated as "the market," a theory not embraced by democratic theorists or political scientists. On the contrary, this argument blithely sidesteps the crucial role of people, including those with little or no money, in agenda-setting, decision-making, and other participatory processes. The argument is basically one of uninformed wishful thinking. It purports an easy "answer" to issues of democracy and public problem-solving. However, the direction taken by technology will not be decided by quality of arguments but by actual results in relation to these questions: What will people use in the future, what willl they use it to do, what roles do they play, and which policies guide the technological direction?

The argument in this paper is not based solely on the idea that our research is too slow. If that were the only reason then the chore before us might be to speed up the research somehow; make it more efficient by, say, "cutting out the middleman" or outsourcing it. The speed of change in the non-academic world - and the significant implications of the changes we're seeing in relation to the build-out of information and communication technology and its implications - are the most relevant points here. Yes, research should be faster, but, more importantly, it should be relevant (without sacrificing rigor) and this points most profoundly towards a deeper and more enduring relationship between communities (i.e. people) and the academy. Current approaches to research don't need to be replaced; they do however need to be expanded, mostly by transcending self-limiting and somewhat arbitrary boundaries between what researchers should be doing and what researchers are allowed to be doing.

There is much to be gained through improving the relationship between academics and the community. At the same time there are risks to each side. Part of the problem is where to draw the line between what is research and what is "just" informed inquiry (or activism or community development or all three). Another part is drawing the line between research and development, implementation, and sustaining. The "pecking order" of the various approaches, where community work becomes less-than in relation to the other academic pursuits - perhaps because it perceived as less theoretical - is also relevant. The way of thinking that asserts that science is entirely objective and value-free also presents friction. The approach may serve to absolve scientists of responsibility beyond the immediate boundaries of their research and their discipline. Unfortunately, it can promote irrelevance and moral confusion by denying them a voice in the discussion (including possible critique or warnings) and future deployment of the fruits of their labors - except of course if they were immediately remunerative. The belief in the inherent objectivity (and, hence, superiority) of measurement and numbers implicitly denigrates the idea of salient and local knowledge which is often so critical to community use of technology. Physics or chemistry, for example, search for universals - facts that would be remain forever true regardless of the context. Social science, on the other hand, can only be characterized at this level - if at all - by statements that would be banal at best, useless (or useful in bad ways) at worst.

Computer scientists and other technology designers could become more central in the ongoing evaluation and evolution of community use of technology. They could extend their work beyond the one-offs, demos, proof-of-concepts and experiments-in the lab, not in the streets - and into the development of open, evolving and enduring infrastructures. This would necessarily involve other community members (see next section) and researchers (particularly social scientists) from other locations in the academy. There are many ways in which a transfer to civic use might be accomplished, including anything from making their products open source, to involving community members in the design of artifacts or services, to establishing and serving in a local community-innovation organization. And educating the public is especially relevant but not generally as fundable as research.

The community of stakeholders working in this area also needs to be expanded. Current divisions between data-gathering and policy development can lead to problems. Academics may object to the way that the data they've produced is misinterpreted or simply inserted instrumentally into a system of values and priorities at odds with their own. Social science research, for example, may reveal that certain groups tend to score lower using some testing instruments than other groups in certain types of cognitive skills. These results may be used by others to justify spending less on educational programs aimed at those groups - while the researchers thought that these groups deserved additional support in order to improve their scores.

While not the subject of this short article, the question of the legitimacy of social science and other academic / scholarly pursuits will not be brought up only through the efforts of those working solely "at the grassroots" from the "bottom up." Support for these enterprises will not magically appear without sustained effort directed towards our own community and fellow academics and funders. (But, in the absence of this support, we should acknowledge that working without remuneration - if it is plausible - brings its own rewards, more autonomy to name but one.)

STRONGER COMMUNITY FOCUS

The questions of why and how researchers should engage with communities is deeply related to the purpose and practice of community informatics. Community informatics is a field for researchers and practitioners working purposefully. We have further responsibilities towards the communities we are engaged with in addition to providing interesting facts and theories about how they use (or don't use) technologies to the research communities so that new research can be conducted. One such responsibility is to "do no harm". The second goes beyond the first by suggesting that we are actually striving, sometimes strongly and sometimes less so, to empower the communities we work with. The relationship should be building capacities including the ability to define and develop its own research agenda to be conducted in partnership with the academy (Bruce, 2008). These responsibilities place constraints on activities. (For one thing there would, in many cases, be a shift from "big data" use to more reliance on the salient knowledge (Ganz, 2009; Defilippis, 2004) specific communities need). More significantly, however, the responsibilities open up new opportunities which, along with ideas for what to do with obvious opportunities, are discussed in this article.

A stronger community focus suggests several changes, many of which have become more common. Due to myriad problems from the historical "drive-by" approach to community research in which researchers would enter a community, gather data there and then vanish, many research projects are adopting community-based participatory research practices. Communities also question the nature of the research projects in which researchers are there one day and gone the next. Clearly longer relationships are needed - but the relationship often ends at the same time the grant money runs out

Based solely on the expression "community and technology" that motivated this and other position papers in this special section, the academics who study that interactive relationship are omitted from the field of "community and technology". Whether this is intentional or not, it reinforces the view that researchers study communities and technology from the outside and the idea that researchers are - or can be - members of the community and can work collaboratively as peers on analysis, design, development, and other engaged enterprises is not always considered.

A focus on communities and technology should engage communities more directly and more strongly. Below are four important approaches that would help advance this focus. Each of the bullet points below the various approaches suggests several significant implications. Note that they are not exhaustive, nor - of course - are they trivial to institute. Other people with interests in this field are encouraged to improve this list.

Invite the community into our enterprise

- We must make our conferences and other events affordable and accessible

- We must learn more about the communities we work with and build enduring relationships

- We must involve the community in research; they can identify research questions and priorities and, presumably - with some assistance - lead the inquiry effort

Co-design with the community

- We help provide design tools and other aids

- We share our research goals with them - and find out what they want

- We encourage communities to develop their own research agendas and we will assist them in the work

Serve the community

- We take their current and future needs - and concerns - seriously

- We adopt stances in a general way that support them

- We help promote genuine change

- We develop technology that communities can use - and continue as best we can to ensure that it evolves and is supported

Strengthen our community

- We identify and develop shared resources and projects

- We identify and develop shared challenges and visions

- We collaborate with other communities including activists, civic organizations, community organizers, researchers and academics, students, government officials, artists, musicians, etc. etc.

- We hope to encourage and help launch long-term collaborations that result in campaigns, projects, and useful artifacts or other resources.

We can also make the case to ourselves, our department, our funders, etc. that integrating and embracing community into our work more fully helps strengthen our efforts. Although one of the proper roles of the academy is helping society at large (whose labor and taxes makes academic life possible), the argument that the world needs us is incomplete and misleading. Our work will be richer when we rethink the importance of community and of the human and natural world generally. Our work will be more relevant and, hopefully, the support will come. Ideally because have made the convincing case that it is needed.

What would be lost if community informatics researchers moved their work further in the directions outlined here? I argue here that thoughtful movement in these directions need not sacrifice any of its core values. A stronger community focus need not rule out research or rigorous methodology. On the contrary, it is often the artifacts of the way the academy is institutionalized that need some transformation to help community informatics researchers and practitioners do their jobs better.

ORIENTING OUR ENTERPRISE

How does theory play a role in academic work that is more engaged in the communities that we exist within, that informs and that is informed by our work? Are there intellectual foci that would help orient our community and scholarly work and help strengthen our roles and legitimacy? The theory and practice of civic intelligence is intended to help answer these questions. Civic intelligence is the capacity for groups to work together for the common good, to address shared challenges effectively and equitably. This concept is very much aligned with the goals and practices of community informatics and the goal of collaborative problem solving specifically. It could help serve as a focus for a number of research and practice initiatives and thus foster indirect coordination. The idea of one or more foci is important because collective action depends on implicit and explicit coordination among the players.

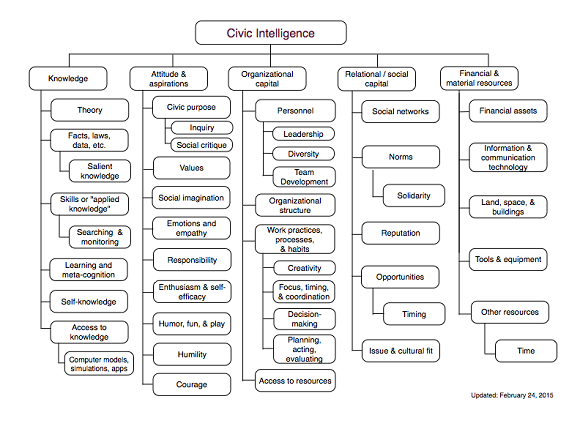

As part of this exploration I have developed a civic intelligence capacities framework that seems to be nearly complete. Among other things, it is intended to be used for diagnosis in relation to our current work as well as planning for enterprises that are advancing civic intelligence - whether they use the term or not! - and that includes the communities and technology community.

We've organized our findings over several years and present the five categories of capacities that help support civic intelligence.

- Knowledge; including a variety of knowledge-based capacities such as theory, knowledge of problems, skills, resources, self-knowledge and meta-cognition (thinking about and improving one's own thinking);

- Attitude and Aspiration; including a variety of capacities that are typically seen as non-cognitive but are essential for civic intelligence such as values, civic purpose, empathy, and self-efficacy;

- Organizational Capital; including the processes and structure of the collectivity that are needed to complete tasks effectively, such as personnel, work practices, and access to resources;

- Relational and Social Capital; including reputation, social networks, social capital, opportunities; and

- Financial and Material Resources; including money, buildings, land, and the like.

The figure below lists the main capacities within each category.

The framework can help us consider the stronger community focus points that were discussed above. Beyond that, the framework could be used to help develop and conduct a transition into a more engaged (and legitimatized) academic / community relationship. In using the framework, two guidelines must be kept in mind. The first is that most (if not all) of the capabilities pertain to any group; each will take on different characteristics depending on the group and the challenges they face. The organizational structure of a large corporation will probably be far more hierarchal than a coalition of non-profit organizations. A large financial company is unlikely to be motivated by social critique such as structural inequality. The second guideline is that although the capacities are presented in a logical and discrete way, the capabilities are not employed autonomously, nor in the absence of ongoing processes. For example, the self-knowledge (column 1) of a group may reveal that the social imagination (column 2) capability should be improved; hence they use their social network (column 4) and financial assets (column 5) to identify and hire people who can promote team development and creativity (both column 3).

The framework could also be used in ways more directly related to this essay's themes: increasing the ability of the academy to more effectively engage in the deployment of ICT that would benefit people. One approach along these lines might be to use the framework to depict how various capacities of, say, academia, might look in an ideal world which could be compared to the reality. The framework can be used to evaluate and diagnose various manifestations of a more engaged, stronger link between academia and community in relation to technology in a broad sense. This could include technological development, community development, policy development, media creation or many other focused activities. The idea of communities identifying strengths and weaknesses within their community using the framework in relation to various goals seems to have potential. It could be determined, for example, that a community needs to develop a broader social network or think about diversity within the group. They may decide to think more about timing or even consider the use of humor within their tactics.

CONCLUSIONS AND NEXT STEPS

This paper advances the idea that the cultivation of civic intelligence can - and should - become a shared objective of the community informatics community. Faced with unprecedented challenges, civic intelligence is urgently needed by communities all over the world. How communities manifest and cultivate civic intelligence will undoubtedly assume different forms in different situations. It will also face a variety of challenges, many of which will be unique to individual communities.

To some degree, the social sciences (especially those which are unrelated to the acquisition of money or power) have been circumscribed - by internal as well as external forces - into a position of relative irrelevance. Social scientists and other relevant academics and researchers need to rethink how their work is conducted - especially since the context of their work has changed dramatically. To a large degree this will mean transcending the traditional limits of the discipline, both externally and self-imposed. This includes who can conduct research, where the line between theory and practice should be redrawn, which research is legitimate and, perhaps most importantly, why research is being conducted - which, in turn, helps inform the how research is conducted.

While universal theories may be largely inappropriate for the scholarly enterprises that we are focusing on here, many if not all of the other activities associated with academic research are still important. Seen from a civic intelligence perspective however, some elements must change. For one thing, design is becoming increasingly important. This means not waiting for others to develop, for example, software for community collaboration, or a new deliberative protocol that meets their needs. Evaluation is very important and it may take several forms. Moreover, because things seem to be more in flux than they were previously, the results of an evaluation might not yield the same results when evaluated a second time. It is also important to embrace natural experiments more consciously. The resources for setting up your own experiment are often not available. Finally, giving more thought to meta-research becomes much more important. It will be important for researchers and community members to better coordinate their work; thus working on larger projects through their work on smaller projects that are worthwhile in their own right but also contribute to a greater whole. It won't be enough to "go it alone."

The six points listed below characterize stages that are likely to be essential in any pursuit of civic intelligence.

- Critique or question - start here even if the critique or question is inchoate

- Learning - necessary at all stages of the process; without this we are lost

- Transparency - people need to understand how things work-especially those processes that seem to produce and enforce the "rules" that we are expected to follow

- Inclusiveness - we need not to just hear the unheard voices, they must be integrated into the decision-making

- Cultural shift - from power politics to problem solving

- Governance sharing - not government "efficiency" and/or citizen "autonomy" - rewrite for academia

In this position paper, the assertion is made that the non-pure (or "soft") sciences need to change in relation not just to the opportunities and threats afforded by new information and communication technologies but to other new realities of 21st century life. Moreover, the changes recommended here are not just reactive and adaptive (to processes presumably out of their control) but assertive and proactive in their role in encouraging a future world that is more sustainable and more equitable for everybody. Courage, boldness, leadership, and compassion - in addition to intellectual vigor and curiosity - will be necessary.

This paper, while developing additional supporting arguments, is very much in the tradition of community informatics (Gurstein 2007) in which empowerment, actualization, social mobilization etc. of communities are explicit goals. Theory and practice are equally privileged and this is built into our self-concept. Communities, also, are the primary foci of attention. On the other hand, we know that communities are not sublime. They come in a variety of shapes and sizes; communities, as with people, are capable of bad deeds and intentions as well as good. Working with them more intensely will not necessarily put an end to all the problems we face. However, working with people and communities at a deep level is key to the "strong democracy" (Barber, 2003) approach that we often advance. Finally, it is becoming clear how absolutely necessary it is to pursue and cultivate the pooled intelligence that Dewey affirms below:

While what we call intelligence may be distributed in unequal amounts, it is in the democratic faith that is sufficiently general so that each individual has something to contribute, and the value of each contribution can be assessed only as it entered into the final pooled intelligence constituted by the contributions of all.

- John Dewey, 1937