Reflective Evaluation of Civil Society Development:

A Case Study of RLabs Cape Town, South Africa

Julia Wills, University of Southampton,

UK.

Marlon Parker, RLabs, South Africa.

Gary Wills, University of Southampton,

UK. Email: gbw@ecs.soton.ac.uk

INTRODUCTION

This project seeks to investigate the processes that led to a successful grass roots civil society development programme. Reflective analysis of RLabs community situated in Cape Town (see section 2 and 3) will define the pre-requisites for community development, using a grass roots development model. This report is a pilot study to develop an interim evaluation method for community development programmes.

At a time when grass roots development has become central to development project delivery for funding agencies, it is necessary to develop an evaluation process that can identify good practice in sustainable development projects (Hardi & Adan 1997). The two main theories of community development are set out in the section 4, where the reasons for RLabs being chosen for this pilot study are given.

As group formation is a flexible dynamic activity, evaluation of activity in development is difficult due to the complexity of actions that occur at the time. Also in the early stages of development action and reaction occur at a great rate. There is a growing connectivity between individuals and groups who may be connected by other networks and brought together for a new purpose. A retrospective view of the process can identify patterns that are mixed in the immediacy of the movement (Freeman 1999). A reflective evaluation process utilising ethnographical research methods was chosen as the research method. The method is described in full in section 5 'Methodology of reflective analysis'. The pilot study identified fifteen people who were present at the foundation of the RLabs project. Analysis of these participants' recollection identified factors that the participants thought were important to the success of a civil society development. These findings described in section 6, are discussed in Section 7 in reference to development theory and practice, with emphasis on the importance of sustainable action in regards to commitment, time, ethos of a grouping and economic factors.

The conclusion in Section 8 reflects on the importance of key factors identified; the limitation of the study and the importance of an ethnographical methodology for intra and inter subject analysis of development programmes. It offers some operational signposts for civil society building.

Athlone Ward: Cape Town Flats

Athlone on the Cape Flats was designated a coloured area under the South African apartheid system and people were forcibly removed to this sandy, ill- equipped district away from the centre of Cape Town, (Western 1981). The area also has a reputation as a deprived area with a drug gang culture, unemployment and a high crime rate (Orgeerson 2012).

RLabs: A Community Development Success

RLabs is an example of innovation of new technology, particularly mobile technology, from a poor community for its own use. Heeks's classifies this type of ICT development as 'Per-poor innovation' (Heeks 2008). RLabs developed from operating community help-lines using its own MXit platform technology in 2008, to become a living lab with business incubator. By 2014, RLabs had established its community model in twenty one different countries, and was running its own academy in Cape Town, (issuing certificates which are recognised as a valid qualification), had developed a social enterprise and leadership programme and was acting as an incubator for new businesses. RLabs is self-supporting; it sells its IT services to numerous local, national and international agencies.

At the end of 2014, the achievements of RLabs included:

- College and university scholarships 592

- Businesses inspired and supported 891

- People employed and economically empowered 23,402

- Free academy training places 31,210

- Jobs created and filled 42,315i

Business generation through the incubator has been particularly innovative. New business ideas in 2014 include:

- Virtual Employment - Provides work experience for skilled labour in the townships of Cape Town.

- EduCycle - Using recycling in exchange for school uniforms and stationery.

- KMG Housing - Providing access to alternative housing for those who are homeless.

- Ignite - Helping school children to discover their passions and talents.

- YouthUp - Addressing the challenge of school dropouts.

- WeGuide - Using technology and legal advice to solve women abuse cases.ii

In summary, by 2014 RLabs had managed to achieve sustainable growth in a poor environment: the project had a fully-fledged academy and had developed a global brand. The research question is, can we identify what was important to the sustainability and success of the RLabs project? To investigate the question fully, it was necessary to place RLabs in context in terms of community development theories.

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT THEORIES

Community development begins with the concept of social groupings. Sociological investigation into development has historically centred on groups that are considered fixed distinct entities in time and space. Describing how a community is constructed from such groupings is no easy task. In many ways the easiest explanation of a community is that of people linked in a physical space, forming a neighbourhood; a place of meeting. However, the terms community and neighbourhood are not synonyms. Concepts of community have moved from locations to groups built around people in contact with each other, (Tonnies, 2001, Sichling, 2008, Gurstein, 2008).

There are two generic processes that enable communities to develop. These are that they are formed as part of either a civic programme, or a civil model of society. These two models are discussed below. The Civil model of society is the one that will be pursued further in this study.

Community Development in Civic Society

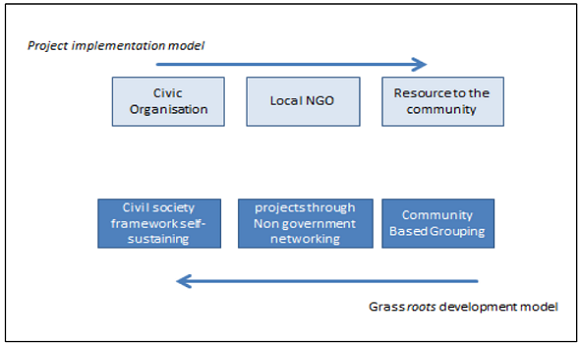

All discussions about civic society involve co-operation between three social elements, namely individuals, a national state and gatherings that happen inside a physical space, (Howell & Pearce 2001). In a civic society model, development of communities is led from a central body external to the locality and focused through established groups; for example non-government organisations that are approved by the central body (Easterly 2006). Development is described in terms of service delivery and provision of utilities. The aim of development is to fulfil national or international criteria for development, e.g. for example health targets, educational targets or environmental targets, (Easterly 2006). Theories of development have emphasised the importance of community participatory programmes for successful implementation of targets, but the direction and aims of development are set by planners outside of the community (Unwin, 2009, Chambers, 1994, Banks, 2010), This model of community development may be labelled 'the project implementation model', see Figure 1: Models of community development.

Community Development in Civil Society - Through Structural Theory

Civil Development is defined by the term 'civitas' which is Latin for public space, (Harris 2003). There is an element of free association of individuals meeting around a common interest. A working definition has been given as,

'civil society meant a realm of social life - market exchanges charitable groups, clubs and voluntary associations, independent churches and publishing houses - institutionally separated from territorial state institutions' (Keane, 2009: online).

People gathering together for a common purpose have been a feature of communities from the time of 'kin, external kin, tribes and clans', (Deakin, 2001: p 59). The theoretical account of civil society began in the Scottish enlightenment period, particularly with Fergusson's 'An Essay on Civil Society' (Harris, 2003, p.22). This thesis was produced at a time in Scottish history when the practice of convening in small groups against the civic state was gaining legitimacy and the concept that people had the right to live under a rule devised by their own groups' ethos was becoming evident.

Following the liberal political strand from the enlightenment, the idea of civil society as,

'An inclusive associational ecosystem matched by a strong and democratic state in which a multiplicity of independent public spheres enable equal participation in setting the roles of the game' (Edwards, 2004, p 94), had become a working model for setting up democratic sovereign states as set out in the philosophical works of Karl Popper and Habermas (Stokes 2009), and also for the formation of societies that can deliver functional outcomes (World Bank)iii .

Community Development in Civil Society- Through Bottom Up Group Formation

Community development from the activity of its individuals had been described as group emergence, a concept made popular by Johnson in 2001 with the publication of his seminal work of bottom up group formation (Johnson 2001) Focusing around common aims and interests, Johnson stated that people naturally group in a way that will create collective activity interest groups. Following this model of community development, sociologists have become increasingly interested in the way that individuals link with others and create associations. An individual's journey through their associations can be described as 'flows'. Relationships can form with various others, which may or may not achieve an established group able to act in a sustainable manner. Modern sociologists investigating flows that form society groupings include Bauman, (1990, 2000), and Urry, (2000).

John Urry, in his work 'Sociology beyond societies: Mobility's for the twenty first century', views movement as key to community development. It is natural for people to meet, merge and divide. Urry states that

'Development of a civil society is based upon auto mobility', (Urry 2000, p189-190).

Bottom up community development has different features from centralised community planned development. There is a community based grouping that forms a non-government organisation to achieve self-determined aims and projects. This framework is self-sustaining as it is fluid and flexible to the changing needs and personnel in the community. Thus, the community development is under the direction of its citizens. The different models of community development are set out in Figure 1: Models of community development.

The freedom to associate, to make links and to make self-determined decisions is central to development of civil society, as set out in Sens' seminal work 'Development as freedom' (Sen 2001). While there has not been a concentration on personal capacities in this study, certain elements in its framework mirror the Capability Approach to Community Informatics as set out by Stillman & Denison 2014. These include an emphasis on association, longitudinal studies, the use of social mapping and a concentration on 'theories of the middle-range, which include theories of design and action that give explicit prescriptions for construction of an artefact' (p202). Rather than study the growth of personal capabilities in individuals, this research looked at how people related together to increase community resources to enable the growth of personal capabilities in a geographical area. Development of community groups from the association model can therefore be seen as a sub-section of the Capability Approach.

Examples of Bottom Up Community Development

Is it possible to find examples of bottom up community development? This section sets out four examples of civil society development, historically, internationally, recent and pending.

American states in historyAn historical example of community development using civil government is in the foundation of some of the initial states in America in the sixteenth and seventeenth century. The Spirit of America, written in 1910 by Van Dyke, explained the foundational ethos of American pioneers as one of social co-operation where small groups wanted to be self-organising (Van Dyke 1910). The rules of social engagement were set by the founding members (Garraty 1991). An example of such a group would be the Quakers who settled in Pennsylvania.

The growth of working class education in the industrial revolutionA second example of grass roots development of civil society is the social movement in England in the nineteenth century that led to the formation of the mechanic schools and the start of technical education for socially excluded individuals.

At a time when the new industrial towns were excluded from parliamentary representation and the growing non-conformist industrialists were barred from Universities and the formal structure of social advance, the only hope for education being available to a wider audience was for the new towns to organise education themselves. The growth of civil society at this time occurred when,

'interest and cause groups either directly or indirectly challenged the English male dominated traditionalist Anglican and aristocratic society' (Harrision, 2003: p79).

This education movement was achieved by people organising technical education through night schools in England and has been extensively researched by Dr Dick Evans in 'A short history of Technical Education' (Evans 2009). In this web based publication, Evans, who is an international and national consultant on further education has written a valuable analysis of how and why further education developed in Britain in the above time period. In 'the Dissenting Academies, the Mechanics' institutions and working men's colleges', Evans describes the main actors and self-help groups that enabled the development of training for working class people from the year 1800 onwards. By 1850 there were over seven hundred independent educational places that followed the technical education model. They offered a number of services, including libraries, training, publications of new scientific societies and news rooms. Other movements were the working men's' colleges. The Sheffield Peoples College is described as an example of a successful college which became part of the social fabric. However, there are weaknesses in using an historical example to describe the process of community development. Written records may allow us to identify actors and links to organisations in the community development process; however the dynamics of flow are not easily recordable without the actors' oral stories.

Big LocalA recent example of grass roots civil society development is the UK lottery funded 'Big Local'. Beginning in 2009, the Big Local programme is situated in 150 deprived areas in England. Big Local's four outcomes are:

- Communities are better able to identify local needs and take action in response to them.

- People have increased skills and confidence, so that they continue to identify and respond to needs in the future.

- The community makes a difference to the needs it prioritises.

- People feel that their area is an even better place to live.iv

There are, by 2014 only a small number of areas that have produced a working committee and are moving into their second year. There may be mileage for evaluation of this programme at a management level but, at the grass roots there is still a storming and forming mentality rather than an evidenced sustainability of group formation. It was felt therefore that Big Local at a geographical level was not at a stage for reflective analysis of factors of sustainability.

RLabs South AfricaA fourth and established example of communities development using civil society is RLabs in Cape Town, South Africa. In 2008 South African Nation television ran its breakfast programme from an area in Cape Town named Athlone Flats. They were interviewing a number of youths who were involved in the pioneering of a new technology which enabled them to operate a community drug and advisory help line via MXit, a text platform. Within two days, when the system went live, the help-line took hundreds of calls from Cape Town and beyond. The RLabs website states that the vision of RLabs is 'to impact empower and reconstruct local and global communities through innovation.' RLabs values are summarised as: a movement for people, of hope, change, opportunity, learning, innovation and a social revolution.

RLabs was chosen as a good vehicle to research community development of civil society as it qualifies as a grass roots innovation, it has shown sustainability and a growth mode (Parker et al. 2013). Also, most of the innovators in the community were still present in the community in 2013.

METHODOLOGY OF REFLECTIVE ANALYSIS

The aim of this paper, as noted above, is to reflect and analyse how a sustainable community developed following a grass roots development model. The question we were asking of the actors was:

"How did they achieve the formation of a civil society?"

The research method chosen to answer this question is a phenomenological reflective analysis of narratives from the community members.

Phenomenology is a philosophy that is defined as

'"phenomena": appearances of things, or things as they appear in our experience, or the ways we experience things, thus the meanings things have in our experience' (Smith 2013).

Based on the work of Edmund Husserl, the philosophy is suggestive of David Hume's thought in the eighteenth century of life lived through the senses. Phenomenology suggests that rather than there being an absolute truth, as people record an event or experience it in many different ways through their senses, truth is best perceived through in-depth observation or narration of a situation. Phenomenology suggests that to get an explanation of any communal event, an accurate account is possible by asking many actors and distilling all the subjective perspectives to synthesise commonalities to collective behaviour, (Sokolowski 2000).

Behaviour is not seen as a purely a decision of the individual but affected by surrounding people (Embree 2002). Dynamic action is achieved by many people responding to each other's ideas, concepts and assets. Therefore by asking, in this case the actors of RLabs to reflect back on how they experienced the RLabs journey, it would be possible to analyse their narratives and synthesise commonalities to the whole group recollections, thus giving themes of commonality of experience (Bloor & Wood 2006).

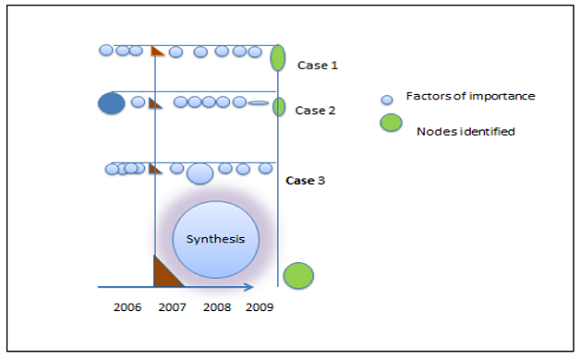

Furthermore, by placing the narratives in chronological order, the identification of common themes for different years will grant us an insight into how the RLabs community emerged, changed and matured through the development process. Phenomenological reflective analysis is illustrated in Figure 2: Method of Synthesis in phenomenological research.

The Research Process: Time-lines and Narratives

The research design was in three stages. First, the gathering of data: this section included the identification of participants through snowball sampling methodology, an ice breaking exercise of asking personal questions of their role in RLabs and the recording of their narratives of RLabs?

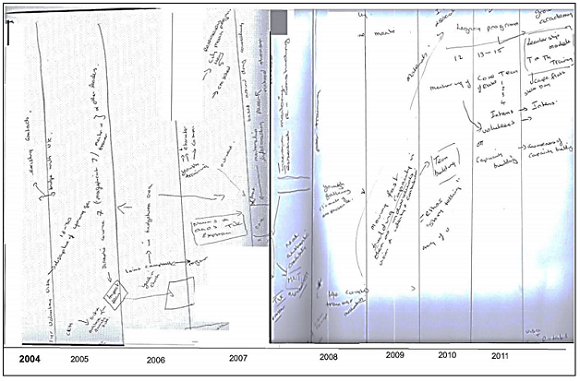

development in the form of an A3 visual aid time-line during unstructured interviews. The use of a blank time-line acted as a visual aid which allowed the participants to have an active role in recording their story and acted as a memory aid. In the interviewing process, participants were able to give a fuller account by using arrows to link events to people or events in the past. An example of this process is demonstrated in Figure 3: Completed timeline.

The second stage was when the issues of development identified in the time-lines were used for initial formation of 'nodes' of interest to the developmental process. These nodes were recorded in a qualitative software program named NVivo,(QSR 2010).

The third stage was when the unstructured interviews were analyzed. The conversations were analyzed through content analysis using the above software which enabled cross-referencing across the participants to create an aggregation of interests and to allow measurement of which nodes, now classed as pre-requisites for civil society development, were important in each year of the development of RLabs.

Identification of Participants - Snowball Sampling

The identification of participants for the study required thought and the ability to dig beneath the official RLabs story. The aim was to investigate the development of RLabs; therefore it was looking back in history. The research was looking behind the written account of the RLabs project. There was no directory of people who had helped in the project at that stage; therefore the sampling method chosen was Snowball Sampling. This is a method where:

"The identification of an initial subject is used to provide the names of other actors. These actors may themselves open possibilities for an expanding web of contact and inquiry... The strategy has been utilized primarily as a response to overcome the problems associated with understanding and sampling concealed populations"(Atkinson & Flink 2004).Figure 3: Completed timeline

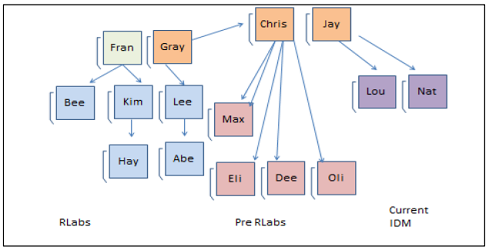

The first point of entry to the community was the technological champion and the manager of the RLabs project identified as Fran and Gray. They introduced the workers of RLabs who had become known as the 'Core Cluster', as they were the original group of people around which RLabs developed. These were named, Bee, Kim and Lee and they introduced family members Hay and Abe in the process.

However the question still remained: "could we identify actors further back in the process?" By asking people in Athlone, it became apparent that people had met before RLabs, particularly linked to Impact Direct Ministries (IDM), a non-government service provider in the area. IDM started as a physical entity in the area in 2005 and had acted as a physical space for community development. These people were involved in RLabs at the beginning and were identified as Chris and Jay, the parents of Gray. The sampling therefore snowballed to include the recent manager of IDM and current workers (Lou and Nat). Jay also identified other people who had been associated with the IDM project and they were added to the list of participants.

Including the link to IDM, the time period for the development of RLabs was set back to 2000 when community work in Athlone started. The Timeline from 2000 was divided into three periods: Pre-Athlone, IDM and RLabs, with the whole project being named ImpactAthlone. The sampling network is shown in Figure 4; Snowball Sampling Network of Athlone Community Project.

FINDINGS

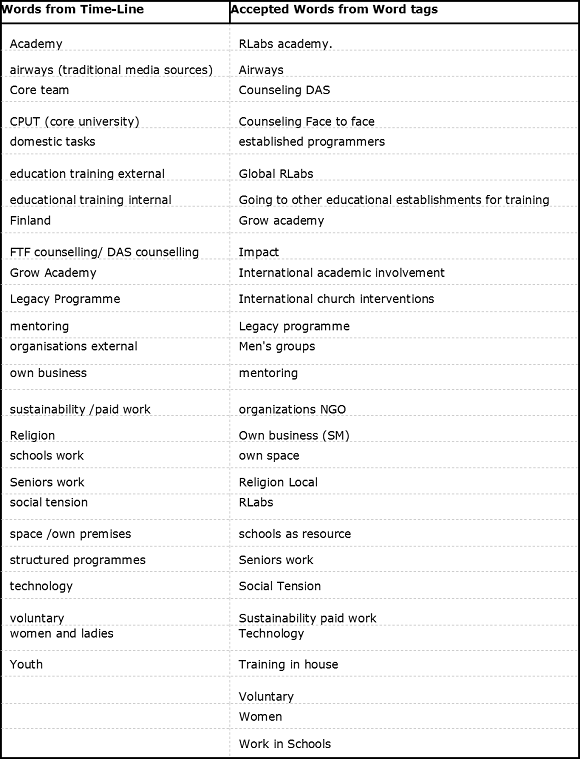

The identification of key people and events in the RLabs story was recorded in fifteen time-lines. Twenty five key words were taken from the time-lines, written with the participants. Word tags of the most popular words from each interview were produced using NVivo software. 34 key words/phrases were identified. These words/phrases are shown in Table 1: Key words identified by the participants as key factors in community development.

The text that had been described was then divided according to the year to which they related. RLabs registered in 2008, but the time-lines produced extended back to 2000. The key words were distilled into a total of thirty one factors that were important to the developmental process. These important words were further classified into three areas:

- Events in the community development process from 2000-2008 (seven key events).

- Key people and the products that they developed in Athlone (eleven key services and economic products and five key people)

- External agencies' involvement with Athlone Development process (ten external agencies).

Events in the Community

According to the participants, the story of Athlone community development leading to the formation of the RLabs project began in 2000 with the idea of offering support to the Athlone community and the idea of a training group who would voluntary attend a residential course for a year. This led to the development of the Impact Direct Ministries, an organisation aimed at delivering services to the Athlone Community, which formed in 2002. A major breakthrough in 2005 was the renting of a space in an enterprise complex on the outskirts of Athlone. This space allowed the training group to operate and enabled an increase in voluntary work, with the beginning of a women's' core team offering to cook, clean and deliver services to the area.

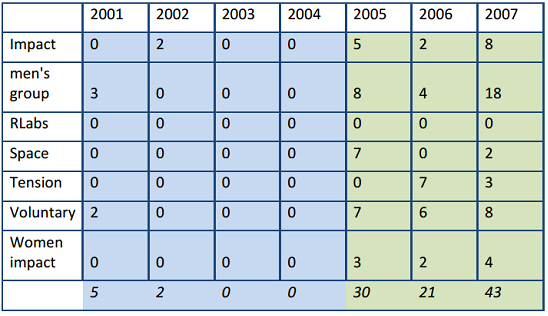

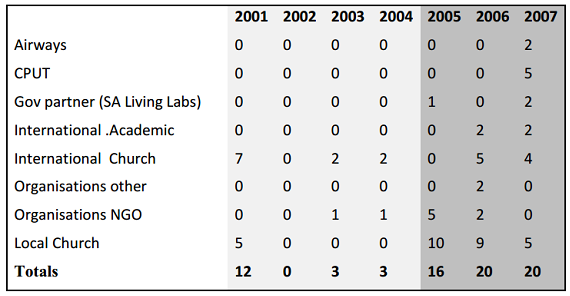

A key social event in Athlone was the outbreak of the 'tik' (crystal Meths) explosion. A feature of this addictive drug was an increase in anti-social behaviour by youth in the area. Drug addicts came to IDM for rehabilitation, in 2007, with the foundation of a permanent 'core' group of men who became resident on the premises. The rehabilitation of the core group led to an increase in services (see below) and an increase in activity in the centre. A summary of events is set out in Table 2: The analysis of main events identified by collective interviews.

Thus according to the numbers in Table 2, the key year for the development of RLabs was 2007, before the RLabs project was officially launched. The challenge in 2007 was to find occupation for the core group. The founder of IDM asked for help from a local resident who had become a lecturer at a local college ['can you do something with these guys?'], (Chris and Fran). Fran became the technological champion linking the core group to an educational establishment and developing the technology of a help line, which was operated by the core group.

Key People and Products in Development

The second stage of analysis was to identify actors who were important in the development of the Impact Centre from 2000 to 2007. Five people were identified by the participants.

- The founders: Most people spoke of 'the founders', who were the local pastor and his wife hereby named Chris and Jay. They formed the initial networking structure that led to the Impact building in 2005 and also sponsored community volunteers on training courses to equip them in community action. Many of these training courses were given free by international teams donating their skills and time to Impact. Courses included basic IT skills and face to face counselling skills. These skills proved the basis for community development (see below).

- The community Champion. The founders stated that they could not have achieved the project without the Impact champion (Lou), member of the local community who was temporarily out of work. After being a factory worker Lou worked voluntarily at the centre, expecting to clean and cook for the men's team. However Lou provided a link to the community. The founders said that ['when they need speak to someone about something, Lou's name came up; Lou is the most important person.']. With training, Lou is today manager of IDM and leads rape counselling for the area, face to face counselling, on line counselling, and the senior and wellness programme of Impact.

- An external mentor. After running a training programme for many years in UK, Eli relocated to Cape Town to help establish a mentoring programme for youth in the community. This group became the first training group. Eli also linked the project with groups in UK who volunteered their skills and time to IDM. Courses included basic IT skills and face to face counselling skills.

- A voluntary office manager, Gray, was in post for most of the period. This person acted as co-ordinator of services, providers and government agencies. This grew into a key role to the production of the RLabs agencies through IDM becoming a founder member of the South African Living Labs initiative lead by Finnish academics Finland academics and the South African government.

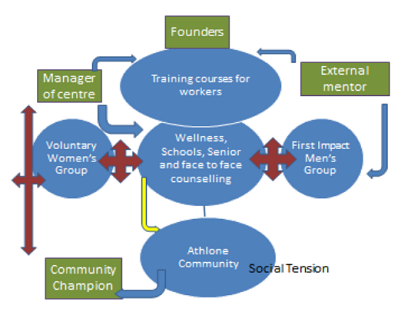

These five people linked directly to the formation of two important social groupings, the training groups and the women of IDM. The relationships between people and groups are demonstrated in Chart 1: People and groups found in analysis.

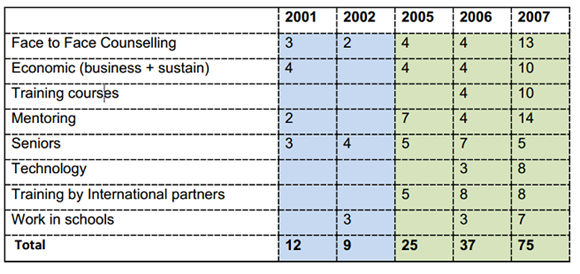

Other factors internal to Athlone and key for community development from 2001 to 2007 were economic factors, internet training, mentoring and the use of technology. The economic factors included people with their own business and sustainability programmes aimed to make the project self-financing. Skills and Services identified in analysis are shown in Table 3 below.

External Agencies

Contextually, IDM worked with other organisations in the development process. These organisations can be divided into local, national and international links.

Working with other agencies on the ground was important to IDM in 2001 and 2005 when change happened in the project. The essential space occupied by IDM was with other church organisations. Working closely with the social services and schools gave valuable long term links to the development of community services. Links to a local college were important in 2007 because it was the employer of the technology champion and offered facilities to the education of the second core group. National agencies became important with the development of the South Africa Living Lab project in 2005.

International links, were important in 2001 with international church networking and also in 2006 with international academic interests helping with the technology development. Also an international academic was important in the mentoring of the technological champion and the core men's group. There was overlap between religious organisations and academic institutions. The key link to communication networks in TV, and dispersing the IDM story through the internet in 2007 enabled RLabs to become known to a television station; key to development in 2008, see Table 4: Key organisations identified in analysis.

DISCUSSION

By reflecting on the findings as described in section 4, it was possible to identity from the participants several key factors that were pertinent to the question of sustainable community development. This section discusses the time frame of the development project, identified pre-requisites for community development, the ethos of the people in the development programme and the micro economic model that they used when preparing for sustainable financial returns the community as a whole.

Looking at Key Years: 2001, 2005 and 2008

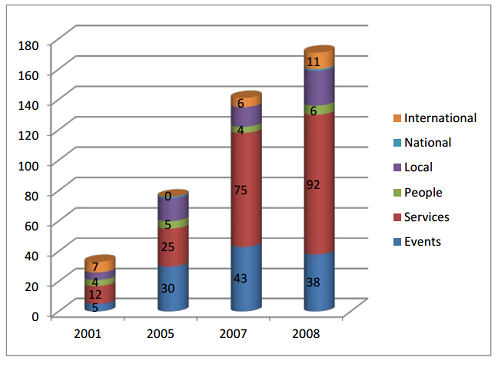

After the identification of key factors in civil development, it is possible to look in depth at the years 2001 when impact first began, 2005 when Impact became a physical presence in the community and formed the first two groups and 2007, the year before RLabs technology not for profit organisation was established, with a for profit business as a financial resource.

In 2001 four key people came together, and planned the first youth training programme group. They also began to deliver services to the area. In 2005 the key event was the renting of the space for IDM in Athlone and the addition of the social champion. The formation of the first men's group and women's group saw a doubling of services and skills in the community. In two years, the impetus had led to the development of many new services and skills developed through voluntary international organisations involvement. The social tension of the Tik explosion, led to the formation of the 'core' men's group and its intensive training programme with mentoring at its heart.

By 2008, when RLabs became a social entity as a not for profit organisation, linked to the South African Living Lab action research project and a for profit business plan, led by the technological champion, the main features for community development had already taken place. These main factors are shown in Chart 2: A chronological demonstration of sustainable development factors.

The link between the community civil development project of Impact and the sustainability of the RLabs was highlighted by the participants. Their views on the importance of the past work in Impact are reported in full below.

'It was not as if they were a separate group, they were still involved with you, and yes they made time for us here...

What we realised is that the things we were doing under Impact which were the foundational stuff, which we couldn't have just RLabs or what we were doing now, without they basis or without that linkage or without that partnership....

Impact always takes care of the softer skills because that is what they are strong at …

So what we have found is as long as you have a strong community partner that is very key like we have Impact and we would not have survived if we had not had Impact..]

[So we still have that partnership we can't lose that partnership if we lose that partnership we cannot do RLabs …

For us we know that RLabs was birthed out of Impact direct and impact direct was basically an organisation that already has a foothold in the community in Bridgetown and it was a community organisation that people already trusted and that and it was easy for RLabs to be to flourish because it came out of Impact an organisation that the community really trusted....

We are still very much connected up to today we are still connected because lots get asked of us and those people are told, these are the mothers the mothers of the centre and must be trusted, must be valued, must be respected...'(various respondents).

Social Pre-requisites for Community Development

The foundation of a civil society of RLabs in Cape Town was investigated using ethnography as a research tool. The following elements have been identified:

i. TIME

An extended preparation period from 2001, where the actors internal and external to Cape Town, were in an informal loose grouping, linked by a common interest in mentoring young people and offering services to the Athlone community. People and organisations key to the formation of RLabs, for example the technological champion, the South African Living Lab group, academic institutions come in 2008: by which time a stable community was place.

ii. ORGANISATIONS

The beginning of making communication links in the community working with established organisations, for example, schools, external religious organisations and social services. Free training of IDM staff, either by external volunteers or sponsorship lead to work with seniors and face to face counselling, this gave IDM a trusted place in the community.

iii. PEOPLE

The leadership group was committed and permanent, although their roles changed over time. Each had their own extensive communication links to key people and organisations

iv. PHYSICAL SPACE

A key turning point was the renting of an Impact Direct Ministries space in 2005. Having the building led to the establishment of the first men's mentoring group.

'People started walking in and all in all, that we spent many, many hours for myself I would leave three or four times a week not earlier twelve or one o'clock in the morning. More and more people got to hear of the help we were offering people so more and more people come families would come the police would bring people and that increased' [Chris].

The above elements for civil society development echo those described by Maton & Salem 1995, who described people taking multiple roles, mentoring each other, committed leadership and a belief setting as central to civil development. The following of a policy to increase people capabilities, skills and community assets, rather than a need approach, fits in with Appreciating Assets, in which personal empowerment is key to development (O'Leary et al. 2011).

The length of time for development and the building of community links to people and organisations was highlighted as key to capacity building (Zakoes R C, Guckenburg 2007). This article also mentions that a 'fuzzy' organisational pattern at the beginning gives flexibility to the development process and that the foundation of the lead agency should be secondary to the gathering of people, organisations and belief system.

Belief System

The main actors from the community, academia and outside agencies were linked together by a common ethos, in this case an overtly religious belief and life style.

The complexity at the heart of civil society development is to describe the mortar that holds the group together. Is it possible to identify what caused the members to give time, energy and money to a process, where personal returns are postponed, and not secure? The importance of the belief in the pertinacity of individuals as agencies of their own destiny was at the heart of historical civil society. The formation of civil society needs a belief system that is based on ethical humanistic features in which the needs of the individual are fulfilled through social processes. However group formation does not have to be for the social good. There is an argument that gangs and community destructive groups use similar psychological processes to build their groups (Alleyne & Wood 2000).

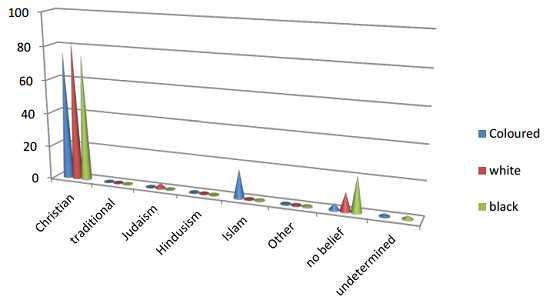

The importance of a deeper belief system in terms of religion in development has been highlighted in academic works (Ahu Sandal, 2011; Lunn, 2009; Tavory & Goodman, 2009; Thackara & Abraham, 2009; Alsop & Heinsohn, 2005; Haynes, 2005; Moss, 1999). For the people of Athlone, their Christian religion and the respect of the 'Pastors' is a deep culturally held belief in the area. The last survey of religious association in South Africa in 2001 showed that in Cape Town there was a homogenised view of religious belief that gave IDM access to the Athlone community. See Chart 3: Religious affiliation Cape Town 2001.

It is also important to note that the faith community reached to a national and international religious network that Impact Direct Ministries was able to link with, enabling the pre-group access to free training, and personal and financial resources essential for this community development. Most of this is not recorded in a written record, but only known through a verbal account of the journey to RLabs.

Economic System

From past experience the founder recalled that

'I began to see the clear link between the community and business and community upliftment was not going to come through charity, it had to come through as well as a social impact there had to be a business economic impact, so the social and economic links that was very clear' [Chris]

An emphasis on individual asset building, as we have seen was important to the Impact Direct Ministries development. The link to training and economic development was also identified in an early part of the process. However it is important to distinguish this model of economic development from macro-economic corporate development as seen in western liberal developed countries.

At the beginning, community economics was based on the supply question 'what do you have?' People bartered time, energy, mobile phones and domestic tasks for a shared communal life style in which they shared food, shelter, opportunities, transport and equipment including free access software. Money as an essential ingredient was not central to the group's development, and where it was needed it was given sacrificially by people involved in the project. Rather than buying in services for debt counselling, the aim was to train people in the community to a registered level where they would get an income from the service and reinvest capital in the community. The idea that they could market the services at RLabs came from one of the reconstructed men's group who realised customers would pay for their services.

This model of economics is becoming known as Compassionate Capitalism and is of growing influence in developing countries. In Asia Society it was described as the 'way of the future' by Asher Hasan, leader of a non-profit social enterprise Arc Finance Limited (Mawjee 2010). For example, payment to volunteers was in the building of their individual capacities and a communal life style, rather than a financial contract.

It appears from the academic literature that Compassionate Capitalism can be described from two points of view; first, changing the traditional corporate business model to think about how they value their workers, environment and their communities (Murray & Fortinberry 2013). Second, Compassionate Capitalism is being seen as a vehicle to build new communities using social entrepreneurship. In 'the New Pioneers: Sustainable Business Success through Social innovation and Social entrepreneurship', Tania Elis states that

'this blending of economic and social values is, in other words generating new social innovations that are creating wealth and welfare for the benefit of society, the environment, people's wellbeing and the health of the bottom line' (Ellis, 2010, p xxi)

The economic system for community development as identified by the success of the RLabs project is based on social enterprise development and asset training in the locality leading to first bartering for services and second the marketing of services to sustain the project and generate not value added profit for an individual but profit to invest in the community.

Limitations

The limitation to this report is that only people who were connected long term to the project were interviewed. There was at least one person who was enthusiastic at the beginning and left the project. The broken connections should be investigated to give a full report. Also projects at the beginning were not always successful. Many first businesses stopped as people moved into college courses.

There is a longer term project, looking at evaluation by producing a ToolKit that would measure each of pre-requisites for community development highlighted above enabling community development groups to highlight areas which need addressing at an earlier time.

CONCLUSION

Qualitative ethnological research has provided a method for in depth analysis of civil society development and has identified factors that have been noted by other researchers. This method has the advantage that it can be used to analyse many community development programmes and compare the results. This will be useful to evaluate the founding of Global RLabs projects but also other multiple community development projects, for example the UK Big Local community development project. Qualitative research following this model may be a useful tool in an evaluation Toolkit for national and international development projects.

This article focused on fifteen early participants in a successful civil grass roots development project: RLabs. The following Social, economic and belief factors were considered important in the sustainability of the community programme.

A - Social factors

i. Time:As one participant stated 'RLabs did not come out of nowhere' (Eli). The time of involvement of people working into the community was up to eight years before RLabs was formed,

ii. People:Key people were leaders who stayed with the project. These people who I have identified as 'hidden people gatherers' need to be recognised and supported by organisations with sponsorships for asset building. Also important, was a social champion, a person respected in the community. The technological champion was called in responding to a need for training in the community in 2005. An external supporter from UK moved to Cape Town to lead the first mentoring programme.

iii. Organisations:Organisations from 2000 to 2005 were fluid and developing. There were members moving into and out of the project. The formation of Impact Direct Ministries was seen as key to all participants. RLabs as an organisation operates in a symbiotic relationship with Impact Direct Ministries: Impact Direct Ministries being responsible for the 'soft nurturing' services necessary to support RLabs.

iv. Geographical Space:The free hire of a physical space in the area enabled the gathering together of people and services that was identifiable to the community.

v. Flexibility and the importance of moving forward:The RLabs project was developed to help ex-drug addict's rehabilitation. Interestingly the formation of another core group at the hostel did not happen. The organisation moved forward in a new direction. There is a key to funding here: because an organisation has success with one group of people, it does not follow automatically that they need to repeat the process with others. New people were mentored through the academic programme in greater numbers.

B - Economic

Renewing a community needs a link to basic micro economics and this is facilitated in a tradition of social enterprise which is a growing model in international civil society development

C - Belief

A unifying belief in the importance of individuals and their assets to the community is essential to the development of civil society. Asset building alone may led to a closed exploited community. Historically and at RLabs there is a link to religious or ideological groups.

Finally, the dynamic social structure allowing people to take risks, explore new opportunities and yet be connected and absorbed at the centre of the Impact Direct Ministries cannot be overestimated. Perhaps the 'softer' nurturing skills identified here are more important in community relationships than they have been credited with in the past. This paper adds to the understanding of community development using ICT by emphasising the human and community pre-requisites behind the technology.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The people of RLabs in South Africa were eager to share their experiences and I thank them for their hospitality.

I would also like on a practical level to thank Dr. Dorothea Kleine and her colleagues from Royal Holloway, University of London on completion of MA on Practising Sustainability in Development, which allowed the formation of contacts essential to completion of the study.

ENDNOTES

i http://www.rlabs.org/impact/ accessed

9/4/2015

ii http://www.rlabs.org/2015/02/10/entrepreneurship-bootcamp-2015/

accessed 9/4/2015

iii World Bank

iv http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/T0PICS/CS0/0..contentMDK:20101499~menuPK:244752~pagePK:220503~piPK:22

0476~theSitePK:228717.00.html

v http://www.localtrust.org.uk/big-local/

Retrieved 6/11/14.

vi http://www.phenomenologyonline.com/scholars/husserl-edmund/

retrieved 27-4-2014.