Male and Female Internet Access Usage Patterns at Public

Access Venues In a Developing Country:

Lessons from Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Sanata Dharma University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Email:

stevanus.wisnu@dosen.usd.ac.id

1. INTRODUCTION

It is believed that providing access to information through the Internet will empower people, particularly in marginalized communities in developing countries . People can access the Internet by various means, including their own devices and public venues. Although some devices are affordable for many low-income people in developing countries, public access venues (PAVs), particularly Internet cafés, still play important roles . People can access the Internet through government-backed PAVs such as public libraries and privately owned PAVs like Internet cafés . The sharp increase in number and usage of these venues demonstrates their vital role for ICT and Internet access in developing countries .

In Indonesia, Internet cafés provide important PAVs as they are found in large numbers in both urban and rural areas. Internet cafés in Indonesia are located mainly in urban areas of Java Island and other big cities but, due to infrastructure enhancement across the country, they are also found in many rural areas, such as many sub-districts within Gunung Kidul and Bantul. The wide spread of Internet cafés in both rural and urban areas makes it convenient for many Indonesians to access information on the Internet.

The important role of Internet cafés in developing countries has led many scholars to explore the patterns of use of these venues, particularly with relation to gender issues . Males and females tend to have different usage patterns in what information they seek and their frequency of use. In addition, males and females often have different perceptions of ICT usefulness and ease of use .

This study examined the differences between male and female Internet café users' attitudes towards accessing ICT, their frequency of use, the types of information they seek, and the challenges they face. It also sought to discover the empirical realities related to gender issues in ICT use in a developing country in order to provide insight for policy makers and professionals who work in this sector.

This case study was conducted in Yogyakarta Special Province. Yogyakarta was selected because of its large number of Internet cafés and their diverse users (Furuholt et al., 2005). In 2009, there were more than 400 Internet cafés spread throughout rural and urban areas of the province. We analyzed data obtained from a survey of Internet access and ICT usage patterns in 20 Internet cafés in rural and urban areas in the Province, using the Mann-Whitney test to check the significant differences between male and female users.

2. BRIEF LITERATURE REVIEW

Public Access to Information Venues.

Public access computing refers to efforts to provide ICT and Internet access in public spaces such as libraries, hospital waiting rooms, malls and airport terminals. Most public spaces are run by governments which provide free access to ICT and the Internet. Due to increasing demand and economic factors, a growing number of public spaces run by private organizations also provide free or inexpensive access to ICT and the Internet. PAVs potentially allow people equal access to information since anyone can afford to use these venues.

In developing countries, PAVs play an important role in providing access to information for underserved communities, as most of their homes are not equipped with ICT and Internet access . In Indonesia, PAVs are especially important since home Internet is not equally available across the country. Most PAVs funded by the government provide free access or charge only very low membership fees to the community . Such PAVs are found in both urban and rural areas in developing countries.

Although the Internet cafés are owned by small private enterprises, these venues can provide affordable prices to consumers . Internet cafés arose in 1990 in the US, and Internet café booms occurred around the world in the late 1990s. In Indonesia, the first Internet café opened in the latter part of 1990 and the association of Internet cafés in Indonesia was established in 2000. Although Internet cafés are privately owned, they play significant roles in providing access to information due to the proliferation of these venues both in urban and rural areas .

PAV clients include high- and low-skilled users who vary as to gender and educational background. In particular, males and females have different Internet usage patterns when accessing the technologies through PAVs . Although prior research reveals differences in Internet usage patterns between male and female users, the differences need to be further explored.

Gender and ICT.

In general, "gender" includes socially-constructed aspects relating to behaviors, activities and attributes of males and females. Traditionally, there are several roles in which males are more dominant than females; for example, males more often decide how the family income is spent. Some governing bodies are also dominated by males. Males traditionally play bigger roles in the public and community systems than females.

Considerable research has been conducted to explain the relationship between gender and ICT. In this paper, we review findings from several studies to show the underlying issues on gender and ICT use in developing countries. According to Geldof , males and females are different in terms of access and use of ICT in developing countries: males access ICT more frequently than females. In Indonesia, they have better ICT skills. Wahid found that more males accessed the Internet than females in the education sector. In addition, Furuholt et al. (2005) assumed that gender serves as a moderator variable between independent variables (such as individual capability, occupation, financial capacity, media exposure) and its dependent variable (such as frequency of visits to Internet cafés). In general, there is a gender-based digital divide: specifically, fewer females access ICT than males in developing countries .

Disparities exist between males and females regarding ICT in the education sector, including their behavior upon accessing information through the Internet. Females tend to be more serious than males in accessing educational materials . In addition, female students have a more highly positive attitude in using ICT than male students . Male and female teachers also have different behaviors when adopting ICT: for example, male teacher trainees spent more hours per week on the computer than female teacher trainees. Male teacher trainees also had more skills in using the computer than the female ones. It can be seen that, in the education sector in which males and females get equal opportunity to enhance their IT skills, males and females still have different patterns of ICT usage.

There are also differences between males and females accessing public venues in developing countries. Males and females do not participate equally in public venues such as telephone-centers and Internet cafés. Males visit Internet cafés significantly more often than females . Additionally, in Internet cafés, more males than females visited pornographic sites. The use of pornographic sites in public venues makes females feel uncomfortable about accessing the venues. Therefore, it can be seen that there is a direct link between convenient use of public venues and gender .

This paper has been greatly inspired by Hafkin & Huyer who stated the need to refine data on gender and ICT in developing countries. One's gender is always relevant where access, use, contents, and impact of ICT are concerned. Although there have been many research reports describing the issues, data from developing countries are very limited.

3. THE CONTEXT OF STUDY

Internet Cafés and Internet Access in Indonesia

Indonesia is located on the equator between two continents, Asia and Australia, as well as two oceans, the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's largest archipelago with approximately 17,508 islands covering an area of 5,193,250 square kilometers of which 2,027,087 square kilometers are land. With an estimated population of 250 million, it is the fourth most populous country in the world. Indonesia gained its independence on 17 August 1945 after the Japanese occupation (1942-1945), prior to which it was a Dutch colony for 350 years. This republic consists of 33 provinces, 445 regencies, and around 69.929 villages.

Computer education and use in Indonesia started in the early 1980s. Use of the Internet by the general public began around 1995. Following this, individuals used computers at Internet cafés and some managed to buy their own computers. In 2008, the number of Internet cafés increased to more than 12,000 widely spread throughout Indonesia. Internet use and Internet cafés are concentrated mainly in the large cities, mostly in Java. The spread to smaller towns and villages has been slow, partly due to the lack of awareness and demand among rural people, and partly due to limited infrastructure.

The government has prioritized using ICT for educational purposes in all parts of the country since 2000. Government and businesses have started using ICT at their maximum capacities. As a result, the number of government-backed PAVs, such as Warintek (Information Technology Café) and Warmasif (Information Society Café, which began in 2005) has grown. Up to now, 87 Warintek venues and 63 Warmasif venues have been established in Indonesia. However, the number of government-backed PAVs is quite low compared to those belonging to commercial businesses or privately-owned Internet cafés

From 1999 to 2007, the number of Internet users increased by 2,500%, from 1 million users to 25 million. Considering the country's population of 250 million, the density of Internet users is still low (around 10%) when compared with that of mobile phone users (146 million or 63%). Two-thirds of Internet users in Indonesia today obtain Internet access through Internet cafés.

Internet Cafés in Yogyakarta

Yogyakarta is a province located in Java (one of the five big islands in Indonesia) This province consists of 4 regencies (Bantul, Sleman, Kulon Progo, and Gunung Kidul) and one municipality (Yogyakarta).The province of Yogyakarta, our research region, had a population of 3,434,534 in 2007. The population density in the city of Yogyakarta is 13,881 persons per km2.. The city of Yogyakarta is known as an education and cultural center in Indonesia. There are around 120 tertiary-education institutions and many arts and cultural centers. Many artists, culture enthusiasts, and students from many parts of Indonesia with different cultural and religious backgrounds have come to live in this city. There are also many small and medium-sized handicraft enterprises, which contribute to the economic growth of Yogyakarta, as do its educational activities and tourism .

In line with the increasing demand for Internet access in Indonesia, the number of Internet cafés has been increasing in Yogyakarta, with the highest number of new players in this business in 2000. There were around 400 Internet cafés in Yogyakarta Special Province in 2009. At the time of this empirical study, September 2009, the number of Internet café users was quite high.

Internet cafés in Yogyakarta are typically found in simple, relatively low-cost premises, with service limited to cyber activities. An Internet café in this city has from 1 to 20 computers. Typically, they have 6-9 staff divided into 3 work-shifts (08.00 a.m.-4.00 p.m.; 4.00 p.m.-12 midnight; and 00.00-08.00 a.m.). Each shift has 2 or 3 staff serving the customers. They assign a computer to each customer and collect the money after the customer ends their session. Most Internet cafés are open 24 hours a day. Some offer more facilities and services to make users more comfortable, such as air conditioning, separate non-smoking areas, soft drinks, and snacks. The cost of access is also reasonable, generally around 2,500-3,000 rupiahs (0.26-0.31 US$) per hour from 08.00 a.m. to 8.00 p.m.; the rate is cheaper, at around 2,000-2,500 from 06.00 a.m. to 08.00 a.m., and cheapest, at 1,500-2,000 rupiahs from 03.00 a.m. to 06.00 a.m.

4. METHODOLOGY

This paper is based on a survey of users of Internet cafés in Yogyakarta Special Province, in both urban and non-urban areas, in 2009. A questionnaire developed as part of the project on public access to information and ICT venues, which was led by the Mobile Government Consortium International and the Centre for Information and Society, University of Washington, was the main research instrument for this study. However, we also conducted interviews with Internet café users to help interpret the findings.

The respondents of this survey were Internet café users in 20 Internet cafés in Yogyakarta Special Province. In this research, we defined urban or non-urban areas based on the population density of the Internet café locations. Based on our simple city-tour observations, we decided that the urban areas in Yogyakarta are the areas bound by the ring roads surrounding the City of Yogyakarta. We divided the City of Yogyakarta into 5 parts: north, east, south, west, and central. We chose 2 Internet cafés in each part, totaling 10. For the non-urban areas, we selected 4 Internet cafés in Bantul, 1 in Kulon Progo, 1 in Gunung Kidul, and 4 in Sleman. We selected more Internet cafés in Bantul and Sleman because the numbers of Internet cafés in both regencies are higher than in the other two regencies.

The population density in Bantul is 1,641 persons per km2 (Bantul Statistical Bureau, 2008), for Sleman it is 1,813 persons per km2 (Sleman Statistical Bureau, 2008), for Gunung Kidul it is 461 persons per km2 while for Kulon Progo it is 786 persons per km2 .

There are fewer Internet cafés in non-urban areas, but they can be found in each sub-district of the non-urban areas. The researchers visited each selected Internet café to conduct a short interview with the operator and several users. We also distributed 20 questionnaires in each Internet café. Finally, we obtained 400 respondents to the questionnaires.

The questionnaires were distributed from August through October 2009. For analyzing the survey data, we applied the Mann-Whitney test using the SPSS software program to check the significance of the difference between male and female users in their information-seeking behavior, purposes of ICT uses, and frequency of use.

5. FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Urban Respondents

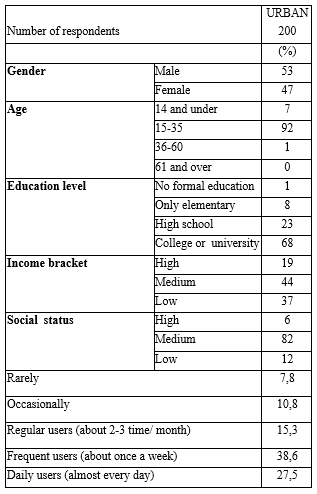

Urban respondents were categorized by gender, age, educational background, income bracket, and social status. 53% of the respondents were male and 47% were female, indicating that more males used ICT in PAVs than females. This finding is similar to the pattern of ICT usage in developing countries presented by several scholars . Most of the respondents' ages ranged from 15 to 35. In the other words, most of them were productive young people. We also found that most of the Internet café users were educated people; few users (1%) did not have any formal education and around 8% had only an elementary education. In urban areas, most users (68%) had a college or university educational background. Similar research conducted by Furuholt et al. showed that most Internet café users in Yogyakarta were young, educated people. This indicates that there has been no change in terms of the users' background since 2004.

We also found that 37% came from the low-income bracket because most of them were students with limited pocket money; 82 % of the users had medium social status. In Yogyakarta, it is usually people with that status who have the opportunity to pursue their education up to high school or university. Table 1 below describes the urban-area respondents'' profiles.

Internet access by

gender

Internet access by

gender

We studied the relation between gender and Internet use in urban public venues in terms of individual's information seeking behavior, purpose of the ICT use, frequency of use, and barriers in using ICT in Internet cafés.

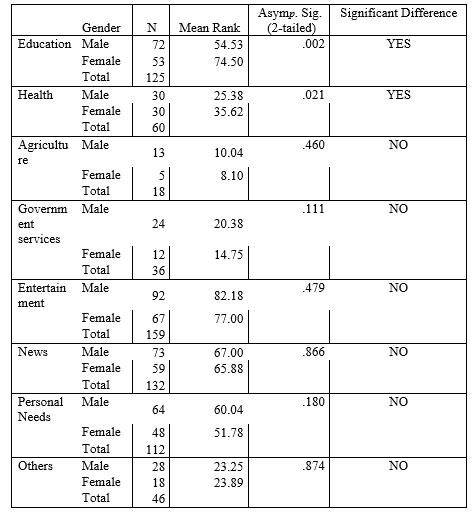

Information-Seeking BehaviorInformation-seeking behaviors were examined based on the types of content accessed by the ICT users. Respondents marked the options that best described their interests in accessing information over the Internet. The content accessed was assigned to eight categories: education, health, agriculture, government services, entertainment, news, personal needs, and others. Respondents to the questionnaire filled in percentage values for the content that they accessed while visiting an Internet café.

Our empirical data shows a significant difference between male and female users in accessing educational content (p<0.05). The number of male users accessing educational content was higher than that of female users (72 vs. 54), but the mean rank of female users was higher than that of male users (74.5 vs. 54.53). Female users tended to visit an Internet café for content related to their education, such as digital materials, more often than male users.

This finding is similar to those of Wahid and Green , who found that female users in Indonesia and in the Asia-Pacific region tended to be more serious than male users in accessing educational content and using ICT for education-related activities. It also indicates that most female users are educated people, as revealed by Hou et al. .

In accessing health information, female and male users also showed a significant difference (p<0.05). The absolute numbers of male and female users accessing health information were equal, but the mean rank of female users was higher than for male users (35.62 vs. 25.38). In particular, 6 female respondents stated that they accessed mainly health information through Internet cafés. This finding aligns with Bakar and Alhadiri who found that female users are the primary seekers of information related to health for themselves and their families. One reason is that females are dissatisfied with the health information already available to them and want to explore more . In other words, women are more active in managing health care for themselves or their families by way of seeking health information via an accessible medium like the Internet .

Our empirical data shows no significant difference in interest between male and female users in accessing agricultural, government services, entertainment, news, personal needs and other kinds of information (p>0.05). Only 18 urban respondents sought agricultural content when accessing the Internet: 13 male and 5 female.

Regarding information on government services, the mean rank for the 24 male users was 10.64 and that for the 12 female users was 8.10, but this difference was not statistically significant. The low number of respondents in this category reflects the lack of online government services in Yogyakarta.

More male users (92) accessed entertainment content and their mean rank (82.18) was higher than for the 67 female users (mean rank 77.67). However, the difference was not statistically significant (p>0.05)

There was no significant difference, either, as for accessing news content. The total number of respondents who accessed news contents was 132: 73 males and 59 females. The mean ranks were almost the same: 67 for male users and 65.88 for female users.

Male and female users did not show any significant difference (p>0.05) in accessing content related to their personal needs. The absolute number of male users (64) accessing the Internet for information related to their personal needs was higher than that of female users (48). The male users' mean rank was higher too (60.04 versus 51.78).

When seeking other kinds of information over the Internet, male and female users did not show any significant difference (p>0.05). The absolute number of male users accessing other content was higher than that of female users, but the mean ranks were almost the same (23.25 for males and 23.89 for females).

Table 2 below summarizes the information-seeking behavior of male and female users in Yogyakarta.

ICT Services

ICT Services

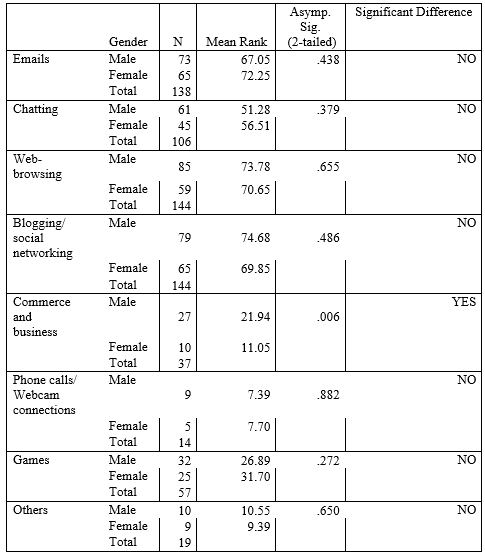

Our empirical data show some differences between male and female users in their purposes when using ICT. The results of our Mann-Whitney tests show that male and female users had a significant difference in terms of their use of ICT for e-commerce and business (p<0.05). Only 37 of our respondents used ICT for e-commerce and business purposes. Most of them were males (27). The mean rank of male users was 21.94 whereas female users' mean rank was 11.05.

Comparison by gender using the Mann-Whitney test showed no significant difference for email (p=0.438), chatting (p=0.379), web-browsing (p=0.655), blogging and social networking (p=0.486), phone calls and webcam connections (p=0.882), games (p=0.272) and others (p=0.650)s.

More males than females visited Internet cafés for these purposes. Table 3 below shows the absolute numbers and mean ranks for the various categories of Internet use.

Frequency of

use.

Frequency of

use.

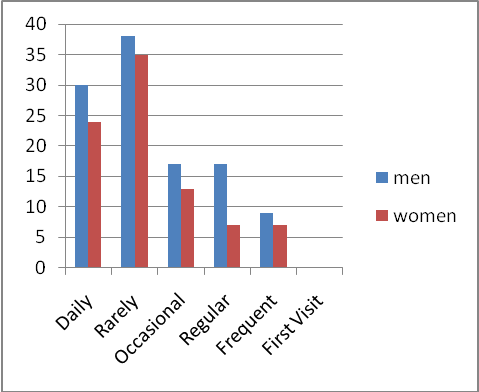

The results show that more male users visited an Internet café than female users. Of our respondents, 30 males visited an Internet café daily, while 38 did it weekly and 17 males regularly, approximately 2-3 times per month. As for females, 24 of them visited an Internet café daily, 35 weekly, 13 did 2-3 times per month, and 7 once a month. The interesting point is that no respondent stated, "This is my first visit to an Internet café". The details of visit frequencies can be seen in Figure 1 below.

Respondents were asked about barriers to their use of the Internet, such as distance, hours of operation, cost, lack of skills, inadequate services, language, insufficient contents and others.

The data show that the number of males choosing location or distance as a barrier was higher than that of female users (35 and 20, respectively). Most respondents were students living in boarding houses during their studies and most of the Internet cafés surveyed are located near their campuses. Since most female students choose to live near their schools but many male students live further away, we concluded that this accounted for more male users' reporting of distance as a barrier.

Hours of operation were not a significant barrier. Since all of the Internet cafés surveyed were open 24 hours a day, respondents could visit an Internet café any time they wished to.

Fewer male than female users claimed the lack of skill as a barrier to accessing the Internet. According to Green , in many developing countries, women are behind men in terms of mastery of technology. Wahid also described Internet adoption by female users as affected by the perceived ease of use. Women tend to use ICT when it is easy to use, but men are more likely to explore technology.

Non-urban Respondents

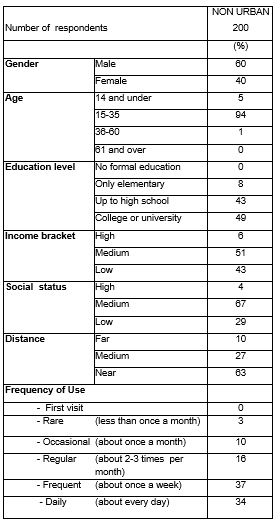

Table 4 below describes the profiles of Internet café users in non-urban areas by gender, age, educational level, income bracket, and social status. In non-urban areas, 60% of Internet café visitors were males, while only 40% were females. In terms of education and age, they were similar to users in urban areas: 90% were aged 15 to 35; 49% had a college or university education level, and 43% of users had a high-school education level; 29% had a low social status and 43% had low incomes.

Internet Access by

Gender in Non-urban Areas Information Seeking Behavior

Internet Access by

Gender in Non-urban Areas Information Seeking Behavior

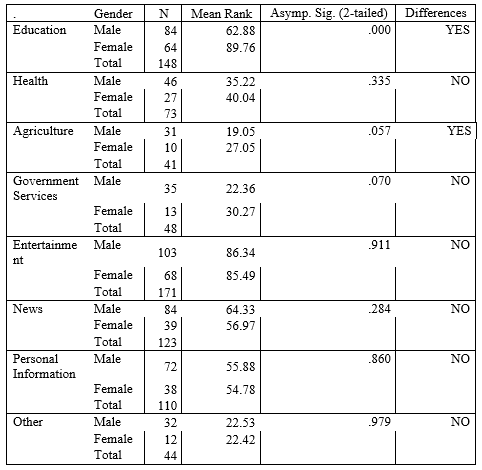

We compared the information-seeking behavior of male and female users at an Internet café in non-urban areas. As for urban areas, the content accessed by users was grouped into 8 categories: education, health, agriculture, government services, entertainment, news, personal needs, and others. Each respondent reported a percentage for each category of information they accessed when visiting an Internet cafe. Then, we analyzed the data using the Mann-Whitney test p<

The research results show that male and female users in non-urban area were significantly different when accessing educational content (p<0.05). Female users showed more interest in accessing educational content than male users (p = 0.000): 64 female users accessed educational content with a mean rank of 89.76. For male users, the number was 84 with a mean rank of 62.88. This result is similar to that for urban areas. Green and Wahid also found a similar result when they investigated the information-seeking patterns among men and women.

Also, there was a significant difference between male and female users in accessing agricultural content. Table 5 shows that 31 males, with a mean rank of 19.05, accessed agricultural content whereas the 10 female users had a mean rank of 27.95. We can infer from this that female users were more interested in accessing agricultural content than male users.

Based on the Mann-Whitney test, we did not find a significant difference between male and female users in their interest in accessing other types of information. Of the respondents, 46 male users accessed health information (mean rank 35.22), whereas only 27 female users (mean rank 40.44) did. Information on government services was sought by 35 male users (mean rank 22.36), while the 13 female users had a mean rank of 30.27.

The number of respondents who used the Internet to access entertainment sites was higher than for any other category. Of the 171 respondents, 103 were male users with a mean rank of 85.49, and 68 were female users, with a mean rank of 85.49. Moreover, one of the respondents always accessed entertainment when visiting an Internet café.

In non urban area, it can be seen that male and female users differ in terms of accesing agricultural content and educational content. The details of our findings can be seen in table 5 below.

ICT services

ICT services

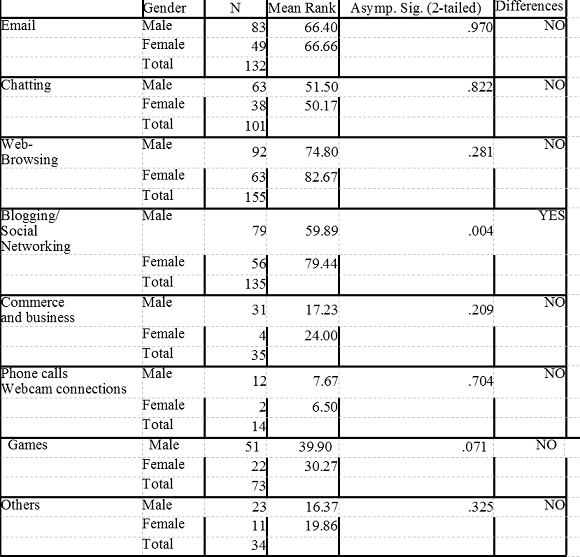

The result of the Mann-Whitney test shows a significant difference (p<0.05) between male and female users in terms of ICT adoption for blogging and social networking. The number of respondents who used ICT for blogging and social networking was 135, consisting of 79 males and 56 females. The mean rank for male users was 59.89; and for female users, it was 79.44. Female users had a higher tendency to use ICT for accessing their blogs and social networking. Three female respondents said they always used ICT for blogging and social networking when visiting an Internet café.

There was no significant difference (p>0.05) between male and female users in terms of the adoption of ICT for purposes such as emails, chatting, web-browsing, commerce and business, phone calls and webcam connections, games and others. The detailed results can be seen in Table 6 below.

Frequency of use

Frequency of use

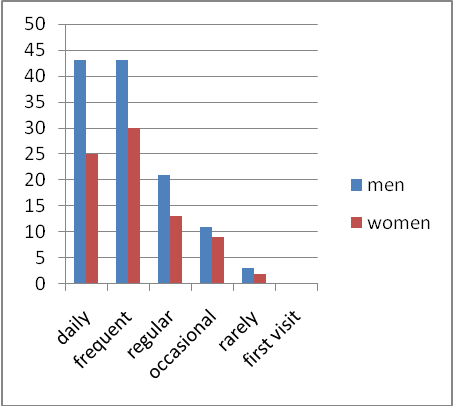

Our empirical data show that overall more male users visited an Internet café than female users. Male daily visitors reached 43, while only 25 females were daily visitors. Thirty female users visited an Internet café weekly. There were 21 male users who visited an Internet café 2-3 times a month; for female users the number was only 13. Only 3 male users and 2 female users visited an Internet café about once a month. As in urban areas, no users stated that it was their first visit to an Internet café. The details can be seen in Figure 2 below.

Barriers to accessing an Internet café by male and female users in non-urban areas were categorized as location, hours of operation, cost, lack of skills, inadequate services, language, inadequate contents and others.

As for location, or the distance to an Internet café from the respondents' residence, 26 male and 10 female users considered it a barrier. A similar proportion was observed for hours of operation, where 11 male and 5 female users considered it a barrier. Not all non-urban Internet cafés were open 24 hours a day, so users could not always get access the whenever they wished.

More female than male users considered lack of skills a barrier, which indicates that males were more skilled than females in using ICT. However, more male than female users chose "inadequate services" as a barrier. Also, more male than female users chose "not enough content." We therefore conclude that male users tended to need a wider variety of services and content than female users did.

More male than female users chose language as a barrier, from which we conclude that female users were more familiar with English. Finally, more male users chose "others" as a barrier than female users.

The barrier most frequently indicated by respondents was cost, reported by 34 males and 27 females. This must be related to their incomes: most of these users were unwaged young people who relied on pocket money from their parents.

6. CONCLUSION

This study raised a simple question: "What, if any, are the differences between male and female users of Internet cafés in a developing country?" From its results, we conclude there are some significant differences related to gender. However, given rapid changes in the society in the years since the survey, particularly equality between male and female are getting better which potentially also link to their access to the Internet, these results are suggestive rather than conclusive.

Firstly, based on the respondents' profiles, the number of male users who visited Internet cafés was slightly higher than female users in both urban and non-urban areas.This finding is consistent with previous studies. Most respondents, both male and female, were young, educated people of middle class social status. However, it is not clear whether social status is a relevant factor in this difference.

Secondly, there were some statistically significant differences between male and female users as to the types of information accessed. Female users were more interested in educational content than male users in both urban and non-urban areas.This finding is consistent with the previous studies exemplified by Wahid and Green. Also, female users in urban areas were more interested in accessing health content which is consistent with the work of Bakar & Alhadiri . In non-urban areas female users were more interested in accessing agricultural content, than their male counterparts.

However, there was no significant difference between male and female users in accessing content in other categories, such as government services, entertainment, news, and personal needs.

Thirdly, in terms of ICT use, there were some significant differences between males and females. In urban areas, male users tended to have more interest than female users in using ICT for e-commerce and business, as indicated by the male users' higher mean rank. On the other hand, in non-urban areas, female users tended to be more interested than males in using ICT for blogging and social networking. However, there was no significant difference in either urban or non-urban areas between male and female users for such purposes as email, chatting, web browsing, phone calls and webcam connections, games and other purposes.

Next, regarding frequency of use, there was a significant difference between male and female users. Male users visited an Internet café more often than female users in both urban and non-urban areas. About 70% of male users reported visiting an Internet café daily to weekly, while only around 50% of female users did the same.

Finally, we found that distance, cost, content and services were considered the most serious barriers to ICT use in both urban and non-urban areas. Also, some female users in both urban and non-urban areas considered lack of skills as a barrier in accessing ICT.

In general, these findings emphasize that there are still some differences in Internet usage patterns between males and females in developing countries, confirming the conclusion of previous researchers cited that gender still influences how males and females access ICT in those countries. Not all of the differences were statistically significant in this study but enough were to suggest further research is needed. We believe that social changes-for example, increases in gender equality in a developing country such as Indonesia will influence the way males and females access the Internet in the future.

These results can be used to support further development of public access venues in developing countries, especially Indonesia. Most PAVs were not aware of the role of gender in accessing ICT. Policy makers might use these results to develop PAVs and materials that better address the gender issues. For example, once aware that women were more interested in health information than men, policy makers could develop more "woman friendly" health information systems to increase the effectiveness of their programs.

In order to confirm these findings, further research is needed to thoroughly explore the differences between male users and female users in accessing educational and health information and the use of Internet services for e-commerce and business purposes. Research to explore the impact of the Internet on women and men in developing countries is also very much needed.

7. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to Yanuar Nugroho., who has given valuable comments for this paper and also to F.B. Alip, and Judith Mermelstein who has helped us check the language of this paper. Both authors are Indonesian local research partners of the Public Landscape Study, led by the University of Washington. This research is a collaborative project of Mobile Government Consortium International and the Centre of Information Technology Studies, Sanata Dharma University, Indonesia.