Mishkeegogamang Tepacimowin Networks

- Chief of Mishkeegogamang Ojibway Nation

- PhD student in Clinical Psychology, University of New Brunswick

- Senior Research Officer, National Research Council, Institute of Information Technology, University of New Brunswick

1. INTRODUCTION

Mishkeegogamang First Nation is a rural Ojibway community in Northwestern Ontario. Mishkeegogamang community members of all ages use a wide array of information and communication technologies (ICT) as tools in daily life, and as a means to support individual and community goals. This collaborative paper tells the story of how Mishkeegogamang uses ICT for community development, drawing on 17 interviews with community members, and several community member profiles. A basic descriptive quantitative analysis is also provided, giving information on frequency of use of a wide variety of technologies.

The research discussed in this paper takes a community informatics approach (Gurstein, 2003). Community informatics sees Mishkeegogamang's digital infrastructure, technology and services as potential tools for community development and social benefit. Community informatics theory suggests that the introduction and use of ICT into Mishkeegogamang offers the community more capacity for independence, resistance, and social, cultural or economic activities.

A broad range of ICT use by community members will be explored, including the Mishkeegogamang website, the busy yet invisible use of social networking sites, youth and ICT, ICT for health and education, and ICT to support traditional activities. Finally, a section on challenges and needs for facilitating ICT use is also provided.

Mishkeegogamang has collaborated on a rich chronicle of its land and people in the Mishkeegogamang book: The Land, the People, and the Purpose (Heinrichs, Hiebert, & The People of Mishkeegogamang, 2009). The current article is written as a new chapter in that book, documenting how community members use ICT in their daily lives and for community development. There have been no similar past explorations that have addressed this area. In addition, within the broader literature on First Nations in Canada, there have been few to no published accounts of community members' perspectives and uses of ICT.

This study is part of a broader collaborative research project called First Nations Innovation, which explores how remote and rural First Nations are using information and communication technologies for community development.

To date we have also published papers and articles about technology use in Fort Severn First Nation, another community in the Sioux Lookout zone of Northwestern Ontario (Gibson, Kakekaspan, Kakekaspan, O'Donnell, Walmark, Beaton & the People of Fort Severn First Nation, 2012; O'Donnell, Kakekaspan, Beaton, Walmark, Mason & Mak, 2011). We also published an article from both Fort Severn and Mishkeegogamang focused on community members' perspectives on telemental health (Gibson et al., 2010).

Despite the fact that there are some exciting First Nations ICT initiatives, little published research exists on how First Nations community members perceive and use ICT (O'Donnell et al., 2010; Gideon, 2006 and what is needed, from their perspectives, to support continued effective use. For example, a variety of successful ICT initiatives for wellness have been implemented in and by First Nations communities. Within the Fort Chipewyan First Nation community in Alberta, community members are able to connect with Indigenous spiritual Elders in other communities and locations by harnessing the power of videoconferencing and offering a tele-spirituality clinic - this actually grew out of an initial telehealth program (Gideon, 2006). For parenting and guiding our children, Lorainne Kenny of Lac Seul First Nation developed the "Raising the Children: A Training Program for Aboriginal Parents" resource which has since been shared online, in videos and text http://www.raisingthechildren.knet.ca/manual/video). Furthermore, interested individuals can participate in interactive online discussions about the materials. These are only two of many important and inspirational initiatives that use ICT as a tool to contribute to further community development and wellness in First Nations communities.

We know that living a traditional lifestyle is valued by many First Nation community members, and at the same time we know that a growing number of people are connected to the internet and use technologies in their daily lives. For instance, 100% of Mishkeegogamang community members who participated in the interviews reported having an email address; another 76% reported having a computer in their home. For this reason, it is important to explore how technology can positively influence Indigenous peoples' lives.

Clearly, living a healthy, balanced, and more traditional lifestyle, and using modern ICT are not mutually exclusive activities. Building on this argument, the specific ways that technology can support traditional activities will be explored in that respective section. The Mishkeegogamang book also emphasizes how new and traditional can co-exist, "a hunter might be wearing the latest in hunting wear, but have a beaver hat on his head" (Heinrichs, Hiebert, & The People of Mishkeegogamang, 2009, p.37).

The approach taken with the current article, and the greater First Nations Innovation project, is to see individuals as actively engaging with technologies and using ICT as tools for the betterment of their own and their family's lives, in addition to community development. Too often individuals are seen as passive users of technology where in reality there are many passionate people who use technologies as a tool to meet important goals: this paper seeks to highlight these instances, and illustrate how various ICT can be used in purposeful and positive ways. Therefore, community informatics theory will also be applied to the information discussed, to highlight how ICT can enable people living in Mishkeegogamang to address individual and community goals.

At the same time, there is no question that technology use can have negative impacts. Indeed there are many concerns about the negative impacts that technology can have on language, social relations, and lifestyle. However, it also is evident that technology has positive consequences - such as connecting loved ones separated by distance, allowing individuals who cannot leave their home to access medical or mental health care and allowing emergency births to take place safely and within the community.

2. MISHKEEGOGAMANG FIRST NATION

Mishkeegogamang is nestled in an area where Lake St. Joseph meets the Albany river, and is accessible year-round due to a provincial highway which traverses through the community (Mishkeegogamang Ojibway Nation, 2010). It is located approximately 500km northwest of Thunder Bay, and 30km south of Pickle Lake. Mishkeegogamang spans two reserves (often referred to as 63A and 63B), and is comprised of multiple smaller and separate communities (Sandy Road, Ten Houses, Bottle Hill, among others). Approximately 900 residents live in Mishkeegogamang (with approximately 500 community members living off-reserve in various locations).

The Mishkeegogamang community history book, The Land, The People, and the Purpose, is key resource on the community and its background, and is a collaborative work that provides an engaging and important history of the Mishkeegogamang Ojibway Nation. The book was a collaboration of the community of Mishkeegogamang (a variety of community members, elders, leaders) and authors Marj Heinrichs and Dianne Hiebert.

2.1 Origins and Elder Stories

Mishkeegogamang, formerly known as Osnaburgh House Band, is part of the Anishinaabe Nation: it was the first community to sign James Bay Treaty No. 9 in 1905. The land that Mishkeegogamang community members historically and originally lived on is expansive and not limited to the points on today's modern map of Ontario. This emphasis was noted well in the history book where it is explained that Mishkeegogamang's true land and boundaries can only be intimately understood by "hunters, trappers, and elders who have spent their lives here." Nevertheless, the knowledge of the land and its boundaries, as well as community members' first existence and interactions with the land, is ever-present and preserved in the community's oral history. Within the history book, the community members share knowledge and stories dating back to the days of Creation.

According to records, the Ojibway people had first contact with the Europeans at Sault Ste. Marie in 1623 (Heinrichs, Hiebert, & The People of Mishkeegogamang, 2009). It was during this time that Northern Ontario was becoming very popular due to the fur trade. Slightly more than a century after the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) had moved into the Ojibway territory, the Osnaburgh House was founded on July 31st, 1786. Mishkeegogamang took on the Osnaburgh name, being called Osnaburgh First Nation, for centuries until 1993 when the community changed back to its original and real name (Mishkeegogamang Ojibway Nation, 2010).

2.2 Challenges And Areas of Strength

Like all communities and all things, Mishkeegogamang experiences both strengths and challenges. A community member who participated in this research reflected on Mishkeegogamang and some of the characteristics of the community.

"They have a good sense of their own history. And of course, one of the most important aspects of a community's identity is its history; its sense of history; its knowledge of its own history. I think they are also very strong in other cultural traditions. They're very good on the land. They're very good hunters, and they know this area very well. And I think it is part of the fabric of their entire culture, the kind of knowledge that they have, and they pass it down from one to the other. And people like (Mishkeegogamang community member) here. (Mishkeegogamang community member) is a historian really. Like he doesn't have the degree in history or anything but he knows everything there is to know about our traditions and our culture. Like he could tell you about the comings and goings of a muskrat and at the same time, tell you about... the traditional rule of women and child-rearing, going back 600, 700 years. You know, he's that kind of person. There are quite a few people like that here." (Mishkeegogamang community member )

In regard to challenges, the Mishkeegogamang book highlights both the strengths and adversities that the community has faced. Of specific interest to this paper, the rural location of Mishkeegogamang can sometimes present challenges in terms of access to certain services that may not be currently available within the overall community. The geographical spread of Mishkeegogamang can also amplify this. The community could address this situation in various ways, including capacity-building at the community level, as well as considering the use of certain ICT to help address various community goals and to connect them with certain services if certain community members so desire.

Even though the Mishkeegogamang book does not address the use of information and communication technologies, a chapter does look at the use of more traditional technologies, like snowshoes and other tools. Mishkeegogamang elders address the issue of technology in the following excerpt, and it would seem wise to apply this perspective to the use of ICT and newer technologies as well: "technology is a gift given to people by the Creator. If they abuse it, it will be taken away from them. In much the same way that animals and plants must be respected and cared for, so it is taught that technology must also be properly used" (Heinrichs, Hiebert, & The People of Mishkeegogamang, 2009, p.59).

3. COMMUNITY BROADBAND AND ICT INFRASTRUCTURE

In the discussion of the active use of technology in Mishkeegogamang, and the services dependent on that technology, one essential piece of the story is the history of connectivity in Mishkeegogamang. This section describes the history and the key people and organizations that have been involved in developing the connectivity infrastructure.

Broadband technologies require technical infrastructure to function. The technical infrastructure in Mishkeegogamang would not exist without the effort and commitment of key individuals within the community, and a key organization - KO/K-Net. Two individuals have been central to technical infrastructure development in Mishkeegogamang: Jeff Loon, community member and Project Lead in Mishkeegogamang, and Jamie Ray, a K-Net staff member. For the past several years, they have collaborated to help support the technical infrastructure the community depends on. In addition to their contributions, other community members have also helped support technology use in the community "behind the scenes" (J. Ray, personal communication, March 10, 2011).

Prior to 2004, the community's technical infrastructure and connectivity capacity was very limited. Dial-up connections were available but "high-speed" or faster broadband connections were not yet a reality for community members. During this time, certain other communities in the Sioux Lookout zone were able to access higher broadband speeds via new cable or satellite connections to their communities; however Mishkeegogamang was relying on dial-up using regular telephone lines.

Beginning in 2004, due to the work and advocacy of community members and KO/K-Net, Mishkeegogamang received a new T1 cable connection (B. Beaton, personal communication, March 8, 2011). It allowed the development of a community high-speed wireless network and videoconferencing services in Mishkeegogamang. Four videoconferencing units were installed in the community - at the health centre, the Band Office, the Missabay Community School, and the "Safe House." Computer equipment (and subsequent connection to the community network) was also installed at a variety of centres within Mishkeegogamang, including: the band office, school, nursing station, Wahsa adult education centre, Resource Centre, NAPS police station, Tikinagan Family Services, Laureen's store and band finance office.

The broadband build was funded by the government agency FedNor, based on proposal submitted by KO/K-Net and approved in 2003. Mishkeegogamang managed the broadband development in the community, completing all the required project reports and contracting KO/K-Net to do the installations, set-up, and training. Jeff Loon was the community project lead and the technician trained in the set-up and maintenance of the technical infrastructure. KO/K-Net worked with the Bell telecommunication company to bring the T1 connection to the health centre. Furthermore, the Broadband North firm was instrumental in getting the original radios onto the Bell tower to provide service to the Band office.

The community uses a licensed and protected wireless system (J. Ray, personal communication, March 10, 2011). This means that the frequency used has been allocated to the community and other devices will not cause interference.

The research discussed in this paper takes a community informatics approach.. Two towers that were built for this project: one large red tower near the Health Centre, and another tower located at Ten Houses. Nearby buildings or homes obtain wireless internet access from these two key points.

4. STUDY APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY

How are remote First Nation community members using ICT?

What are community members' perspectives on various technologies?

How can ICT be used to support community development in the areas of culture and traditions, health and wellness, and education and the economy, to better meet the needs of these communities?

These key questions are at the heart of the community-based research collaboration between Mishkeegogamang and the First Nations Innovation project. First Nations Innovation is a partnership of three First Nations organizations - (Keewaytinook Okimakanak, Atlantic Canada's First Nations Help Desk and the First Nations Education Council) in Ontario, Nova Scotia, and Quebec - and the University of New Brunswick. This community research in Mishkeegogamang First Nation was conducted in collaboration with Keewaytinook Okimakanak who provided expertise, feedback and support throughout.

The Kuhkenah Network (K-Net, http://services.knet.ca/) is KO's private telecommunications network that provides ICT, infrastructure, and support to First Nations communities across Northwestern Ontario and other locations in Canada. The KO Research Institute (http://research.knet.ca/) is the research arm of KO, exploring issues relevant to First Nations with a particular focus on ICT use. Finally, KO Telemedicine (http://telemedicine.knet.ca/) is KO's community-driven and community-led telemedicine program serving First Nations.

We conducted this research at the invitation of Mishkeegogamang Chief Connie Gray-McKay, and we worked closely with Erin Bottle of Mishkeegogamang (in the photo above, left, with First Nations Innovation team member) who was the community liaison and community researcher for the first phase of this project.

First Nations Innovation team members first visited Mishkeegogamang during a week in February- March 2010. Our community visits included both research and outreach activities (training in video production and a community video festival). The five team members who participated in this initial visit appear above.

In total, we conducted 17 interviews with Mishkeegogamang community residents; 14 in-person and three later on the telephone. Participation was anonymous, voluntary, and confidential, and interviews took approximately half an hour. A random sample was not sought: we attempted to invite and interview participants who held a variety of roles in their community but the sample is not representative of Mishkeegogamang. The interview guide included questions on frequency of technology use and attitudes toward the use of various technologies for different types of community development.

All participants were over 18 years old. Participants held a variety of roles and positions within the community, including health workers, teachers, family members and caregivers (e.g., mothers), Elders, leaders (Band Council members), community workers, part-time workers, technology support workers, and others.

There were 11 women and 6 men who participated in these interviews. The research protocols were reviewed by the research ethics board of the University of New Brunswick

Following the community member interviews, two First Nations Innovation team members returned to Mishkeegogamang in September 2010. The goal was to engage the community members in taking the information collected in the Spring to the next step, and to collaboratively create a story of how Mishkeegogamang community members engage with technology.

During the second visit, we connected with many community members along the way and visited several community hot spots - areas/buildings that were frequented by many community members (the community school, radio station, health centre, band office, etc.). Several helpful individuals volunteered to have their stories of technology use profiled in this report. It is our hope that this article will serve as a springboard and help engage more people in terms of positive use of ICT for community development.

5. ICT USE BY COMMUNITY MEMBERS IN MISHKEEGOGAMANG

Many topics will be examined, ranging from an exploration of how frequently community members use various ICT and what technologies they use on a daily basis, to how they adapt them for educational, health, and business use, as well as supporting traditional activities. Current use will be discussed, along with past use and ideas for future use where applicable.

5.1 How Frequently Community Members Are Using ICT

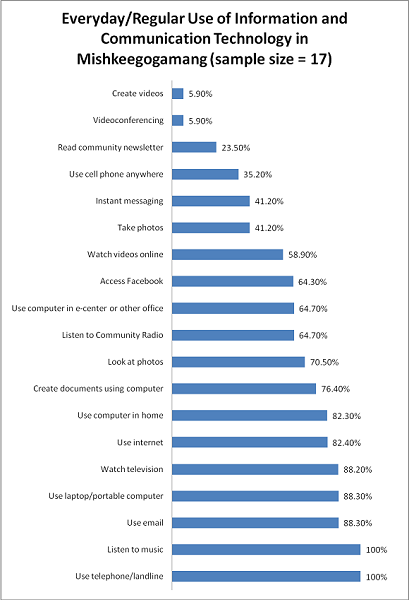

First we will explore how frequently community members are using a range of ICT in their daily lives. Community members were asked to report on how frequently they used a variety of technologies, including "older" technologies (e.g., telephone and newsletter) and more recent innovations (e.g., Facebook). Community members categorized their frequency of use along the continuum of "never" to "daily". For the purpose of depicting regular use of ICT among community members, the chart at the left (Everyday/Regular Use of Information and Communication Technology in Mishkeegogamang) shows regular use - defined as weekly or more often - of various technologies.

Community members reported engaging with a wide range of technologies on a regular basis;: it is interesting and perhaps surprising to note how many community members use email and computers on a daily basis (88.3%). In fact, participants report engaging with computers and email slightly more than they watch television! Watching videos online is also quite popular, though participants are still watching television more often. This could be due in part to the limited bandwidth available in the community, as watching videos online requires significantly more bandwidth than merely looking for information or sending emails.

Clearly, community members are also engaged with technologies that are community-driven and community-led: 64.7% of those interviewed reported listening to community radio on a regular basis, and 23.50% reported reading the newsletter on a regular basis. As for the newsletter, even more participants reported reading it on a monthly basis (65%), since it is often published monthly. However, these numbers appear to speak to the enthusiasm of certain readers who like to engage with the material on a more frequent basis.

5.2 Mishkeegogamang Community Website (http://www.mishkeegogamang.ca)

Mishkeegogamang recently reconstructed their website, and the opening page is displayed in the screenshot onat the left. The website's changes have increased its visual appeal and made it much more user-friendly. The community's focus on making an appealing website is evidence of the importance it places on using ICT to reach out and communicate with community members and visitors. Dianne Heibert was initially involved in developing the website: training of other community members will be occurring in the near future to expand the group who is involved in updating and maintaining the site.

The website hosts the archive of community newsletters, information about community activities and resources (e.g., how to contact the Band Office, the Health Center, etc.), provides important community background information about natural resources and ongoing land claim issues, shares Elders' stories, and showcases pictures of various community members and families.

5.3 Social Networking

Driving through the beautiful rural community of Mishkeegogamang, a passerby would not be privy to the flurry of interactive activity occurring between households in the community. Many community members actively engage with social networking sites, like Facebook or MyKnet.org (see Budka, Bell & Fiser, 2009, for an excellent study on Myknet.org). Community members are using the technology to interact not only with family and friends from afar, but also with other local community members.

Among those interviewed, 14 community members reported having a Facebook page, and five reported having their own MyKnet.org site. Among those participants who use these specific social networking sites, many are accessing them on a daily or at least regular (varying between daily, several times a week, and at least once a week) basis. For instance, 65% of the Facebook users are accessing the site regularly. In addition to using the sites for information exchange and updating friends and family members about issues, avid users often take advantage of the real-time chat/text options, and games that are offered on Facebook.

Several participants noted positive or neutral experiences with regards to Facebook and social networking sites in general, however other participants also noted the importance of being mindful of appropriate use. This issue will be addressed further in the section on Challenges and Needs related to ICT. Finally, there was a tendency for participants to comment on their observations of the younger generation and Facebook: clearly, use of social networking sites is not limited to youth, and a good portion of those interviewed actively engage with these sites, however, community members noticed that social networking was especially popular among youth.

"Facebook is pretty big, right. I just got an account here just a while ago. And I know that's how some kids get messages to each other. Instead of using a phone, they just try to be fancy and use their little Facebook." (Mishkeegogamang community member)

5.4 Community Radio

"We're still kind of 'old school' up here…radio is the number one broadcast system."

-Mishkeegogamang community member

Radio is definitely one of the technologies that Mishkeegogamang community members are most fond of. The radio station has existed for decades, and its programs have changed over the years to reflect community interests: in the early 1990s, the radio station provided lively music for community dances. Mishkeegogamang has adapted the use of the radio for a variety of activities. Community members are able to access all kinds of information via the radio. First instance, community members can access health information via the radio: the community health representatives and local nurses hold monthly radio shows to raise awareness about certain issues. The radio is also used for recreational purposes, like radio bingo. Several members of the First Nations Innovation team feel very privileged to have had the opportunity to meet Theodore Mishene, the radio station coordinator (please see the Mishkeegogamang community newsletter for a profile on Theodore's extensive experience with the radio station: http://www.mishkeegogamang.ca/pdf/MishSept10.pdf).

One First Nations Innovation team member went "on air" with Theodore to discuss this paper and Mishkeegogamang's use of technology. After the researcher finished her English update, Theodore translated into Ojibway. The researcher recalls how fascinating it was to hear both languages being used to engage community members on the topic. According to interview information, 65% of the Mishkeegogamang community listen to the community radio on a regular (daily and weekly) basis. Only 12% of the sample reported "never" listening to it.

5.5 Community Newsletter

The Mishkeegogamang Community Newsletter/Community Update is a creative and positive resource that community members (and visitors!) appreciate. As soon as you arrive at the Band Council you can see the familiar blue Mishkeegogamang colors and logo of the newsletter, with the Mishkeegogamang book and other helpful resources, neatly arranged on a table. The newsletter is also available online, on the community website, so that community members and anyone interested in the community can easily access and read it.

The Community Update documents recent happenings in the community, and has a goal of focusing on positive community development - a refreshing change from the typical media coverage. The newsletter featured pieces by the respected and talented Marj Heinrichs (who was also a co-author of the Mishkeegogamang book), as well by a variety of passionate community members.

In the community interviews, participants were asked about how frequently they submit articles to the newsletter, and how often they read the newsletter. 29% of the community members surveyed reported that they contributed to the newsletter, by writing a story, on a yearly basis if not more frequently (and indeed 12% reported that they contributed on a monthly basis).

As might be expected, an even greater number reported reading the community newsletter. 23% reported reading the newsletter on a regular basis, 65% reported looking at it monthly, and 12% annually. Not one participant reported having never read the newsletter! Clearly, this points to the degree of success and engagement that the newsletter, a more traditional ICT, has achieved within Mishkeegogamang.

5.6 ICT for Traditional Activities

Community members who were interviewed reflected on the ways that technologies can support traditional activities, like being "out on the land". Participants had several creative ideas for ways that technologies could be a tool in promoting land-based activities. For instance, the following participant describes how community members involved in a thriving tree nursery in one community could virtually interact, via the internet or videoconferencing for example, with individuals in other communities to share knowledge around their practices.

"Communities, they can use the internet or telemedicine (videoconferencing), they can share ideas regarding say, for instance, I know in the Wabigoon reserve, they've got a tree nursery there going on and it provides a lot of employment for the people that are living there. So I mean they can always share ideas around and start stuff like that tree nursery and little garden and stuff like that."

-- Mishkeegogamang community member

One individual explained how ICT were being used in school classes to help students explore different geographical areas and different First Nations communities. These virtual visits can compliment real-life and hands-on visits, allowing students to explore some of the land and different communities and locations while seated in the classroom.

While reflecting on the use and integration of ICT with more traditional and land-based activities, it could be interesting to pair some of these virtual explorations using Google Earth with more traditional story-telling and elders' accounts of their visits and past explorations of the same places.

"We started using Google Earth to determine where the school is, like in retrospect to different reserves, and zoom in. I took my kids to Sandy Lake, which is about seven hours north of here...…it's a fly-in (community), but with winter roads. And we zoomed in on the community and we saw where the Northern (store) was and we knew where everything was before we even got there. So yeah, the kids liked that, so I mean that would be a little bit land-based. Also things looking at different climates and things like that, we use Google Earth for. Also, there's a slew of maps around here that we can use."

-- Mishkeegogamang community member

The Ojibway language is integral to culture and community in Mishkeegogamang. A community member reflected on how ICT and translation programs could be very beneficial for community members, potentially supporting increased communication in Ojibway.

"You know, in terms of the use of technology, if we had the things (information) that were translated into our own language, I think that would be very important. It's easy to communicate in English, but it's just as easy for people here if not a lot easier, to communicate in Ojibway."

-- Mishkeegogamang community member

Building on this point, the importance of language is described in the following quote:

"We need to retain language. Language is a big one. Because you know, language is a basis of who you are. It's a basis of your pride, of where you've come from as a Nishnawbe person. To me, the only reason I'm living here today, feeling strong about who I am, is because I learned my language first. I lived on the land with my grandparents."

--Mishkeegogamang community member

Video can be used to preserve traditions and experiences, and these memories can be shared with future generations and used to educate youth.

"I think that even if you're a younger kid growing up, seeing those things (snowshoeing outing) on video kind of gives you a sense of what you should be doing as you're growing up, like at a certain age ... When you hit a certain age, like take part in certain traditions and stuff like that. I think for having that on video and showing the kids while they're younger, …they'll be more inclined to do it as they get older, I think.

So the video's a big aspect of it. Like even the pow-wow that you had on tape yesterday (at the community video festival) would be really great to show young kids and stuff because they might not remember it, like the last time they've been to one or they might not have made the one last year, and they're getting older and they should still know it, just in case they miss it."

-- Mishkeegogamang community member

Another community member explains how ICT could be used to capture traditional experiences that could then be integrated into an educational setting.

"Well, what I was thinking about is if they could record (via video)…when they go on these outings how to properly, say, skin a rabbit. It could be something that can be shared, so if they can't do it, at least they could watch it. They could watch it first and then they could actually go out and do it. I think it's important, hands-on education is the most important thing you can do….and how to properly set a snare…like go through the whole process.

You could use mathematics…it should be this far apart…they could do like a pre-thing and then you could take the kids out and get them really ready to be excited about what they're going to do. They could show them a video about what you're going to do. So what would require videotaping the cultural worker. I think too, it would help to educate…as to why things are done a certain way. And I guess the only other thing is that there are still a number of things that can't be recorded for respect. There are just some things we still can't do with modern technology because it's inappropriate and not acceptable. "

--Mishkeegogamang community member

Elders are a key component of Anishinaabe culture, they provide a precious resource of traditional knowledge and stories. One community member suggested using ICT to help preserve the knowledge of Mishkeegogamang elders.

"The other thing too that could be done is the keeping of elders' testimony, elders' lives…using them to educate your community about culture. Those would be good because our elders are dying away so fast. As long as that's not recorded, it's going to be lost if we don't record those teachings."

--Mishkeegogamang community member

Finally, one community member suggested that video could be used to help document Mishkeegogamang's important ongoing relationship with the land. This material could be used within the community as a shared history but could also be used, if appropriate and/or necessary, to educate "outsiders" on the meaning that community members associate with traditional activities.

"I think it would help out like, for example, it will show that Mish is still involved with land-based activities, especially if you had it posted on the Website …So these land-based activities in video projects, I think, would really help out, like the hunters and gatherers in the community and also to show that these companies and these corporations that, we still exist on our lands. We need our lands. So in that sense, it would also help out like some of the people, too, that are getting videoed and they can actually see themselves and they have to laugh at themselves. And having them be a part of that would be really cool too."

--Mishkeegogamang community member

5.7 ICT for Health and Wellness

Mishkeegogamang has a long history of ICT use in healthcare, and has a health center located on the main reserve (it opened in 1998, prior to that a nursing station was available for community members). This health centre is visited by a physician once every five weeks, and is permanently staffed my nurses. The community telehealth coordinator also works out of this centre. Dating back to the 1970s, Betty Johnson, a nurse who works in Mishkeegogamang, recalls using cameras to take pictures of wounds or injuries of community members who were not able to access health services at an urban center. The images would then be sent to and interpreted by physicians in Sioux Lookout or other urban centers who would collaborate with community health professionals to establish a care plan for the patient.

Dating back even further, health workers in Mishkeegogamang used the radio to participate in "radio rounds" and receive radio updates for every patient who was in care outside of the community. This process allowed for increased communication among the urban and rural mental health professionals, and allowed the Mishkeegogamang nurses to develop appropriate follow-up plans for patients who were returning home. Perhaps most importantly, these radio updates allowed family members who were still in the community to be aware of the health status of their loved ones.

A variety of ICT tools can be used in the area of health and wellness; videoconferencing is one of the most popular technologies and it is often used in telehealth and telemental health initiatives. Telehealth refers to using videoconferencing or other technologies for a variety of health purposes: connecting health care professionals with each other for case conferences, connecting health care providers with clients, providing education, among other activities. Telehealth is used in a variety of specialties - including primary care, maternity care, dental care, and mental health.

Mishkeegogamang and Keewaytinook Okimakanak Telemedicine (KOTM) work together to provide community members with a range of telehealth and telemental health services. Within each community that KOTM partners with there is a Community Telehealth Coordinator (CTC). This individual works at the health center and is responsible for connecting clients and health workers with telehealth services; without this community worker, accessing these types of services would not be possible.

In Mishkeegogamang, Darlene Panacheese worked as the CTC for several years and currently Crystal Kakekayskung is the CTC while Darlene is on leave. According to our data, 18% of participants use videoconferencing (in general - including for health purposes, receiving educational information, etc.) monthly or even more frequently. Next we will explore the positive benefits of telehealth for the Mishkeegogamang community.

Darlene Panacheese,, featured in the photo above with her youngest child, used videoconferencing to access prenatal classes and education to prepare for becoming a mom again. Darlene wanted to remain in Mishkeegogamang with her family yet she also wanted to access prenatal classes which were not offered in the community; by using videoconferencing she was able to connect with a Maternity Center in Thunder Bay. Darlene is definitely one of the technology champions in Mishkeegogamang. She has been working as a community telehealth coordinator for the past several years, and she is very experienced with helping community members use various technologies to support their health and wellness.

When Darlene became a CTC, she was trained on how to use the unit, and she is now very comfortable with it and finds it very easy to use - she jokingly refers to the telehealth unit as her "little friend." Darlene's training has allowed her to become a support for other users in the community: she has travelled to the school and to other locations that have videoconferencing units in order to teach people how to use the unit and engage with others through videoconferencing.

When speaking with Darlene, she recalled her experience of helping a community member give birth. The mother could not make it to the urban center because of a bad storm, and Darlene was called to help the health center staff connect through telehealth with the physician in the urban center. Because the mother knew Darlene and was so comfortable with her, in addition to Darlene's technological expertise, Darlene was asked to stay during the labor and birth. Darlene recalls that the mother said she felt a peace of mind knowing that she was able to give birth in her community while also being under the supervision and care of the physician.

Darlene sees many advantages to telehealth. First, telehealth allows community members to access health services while remaining in Mishkeegogamang. This means that people can remain with their family, and maintain their responsibilities, while accessing healthcare. In addition, using telehealth is an environmentally friendly way to access services - no travel is required! Telehealth also allows for family visits which Darlene feels is very important. If an individual is hospitalized in an urban center their family members can come into the Mishkeegogamang health center to connect with them through videoconference and visit. Darlene sees the family visits as incredibly helpful in terms of providing encouragement and keeping families connected.

Crystal, the current community telehealth coordinator in Mishkeegogamang,, finds many aspects of her job rewarding. One of her favorite activities is the children's dental clinic. During these sessions Crystal (in the photo at right) uses videoconferencing to connect Mishkeegogamang children and their families with dental clinics located in urban areas.

Crystal operates the ENT (ear, nose, and throat scope) to look into the mouths of the children so that the dentists are able to have a complete image of the child's dental health. She enjoys watching the excitement on the children's faces as she says they truly enjoy seeing what the technology is capable of. Who said that dentist visits could not be fun?

Like Darlene, Crystal also sees great benefit in telehealth family visits. She recalls how telehealth has enabled community elders to connect with siblings and family who are hospitalized elsewhere, and she remembers how happy they all looked to see each other. In addition to these types of telehealth activities, Crystal enjoys the educational sessions that are provided.

About once a month, KOTM offers educational sessions via videoconferencing to all community members who are interested. Topics cover a broad range of topics - from mental health to how to complete log reports for local medical drivers. The musical events which take place over videoconferencing are also quite enjoyable to Crystal: young community musicians can connect with each other over videoconferencing to play music for each other and showcase their talents.

Elder videoconferences.. Historically, elder visitation videoconference sessions have been offered to Mishkeegogamang community members on a monthly basis. The purpose of these events is to connect elders from various remote and rural First Nations communities through videoconferencing. This allows the elders to visit with family and friends that they have not seen in-person for years, and provides them with the opportunity to speak in their own language.

Furthermore, these events often have an educational component where there is a brief presentation about a relevant health issue, followed by a traditional lunch that is provided to the participants. During the Christmas holidays, elders unite to celebrate together - singing holiday songs and sharing stories. Fortunately, these events can also be accessed by individuals of any age group and location for they are broadcast by web stream over the internet: that way if an elder or family member is unable for whatever reason to attend the videoconference event (most often held at the health centers), they are able to participate by accessing any computer that is connected to the internet.

Sophie, a community member, is responsible for coordinating the elders' visitations and she says that her favorite part of the event is just being able to see everybody and say hello (she appears in the photo with Darlene). During the last elder's visitation event there were more than five different First Nations communities connected.

Telemental health, noted previously, is the use of videoconferencing and/or other technologies for activities that relate to mental health and well-being, including such things as education, group work (e.g., sharing circles, support groups), individual therapy, assessments, and so on. A previous paper, involving Mishkeegogamang's community telehealth coordinator Crystal Kakekayskung as a co-author, was written about community members' perspectives on telemental health (Gibson, et al., 2011).

The work presented the range of attitudes and perspectives that remote and rural First Nation community members have toward the technology, highlighting both the perceived advantages and concerns. 46% of interview participants reported that videoconferencing for mental health and telemental health was a good idea for their community; 23% reported neutrality; and 31% did not think that it was a good idea.

One of the main conclusions of the paper was that in order for First Nations telemental health initiatives to be successfully, they must be community-driven and community-led. It is our hope that by engaging Mishkeegogamang community members in the discourse about use of technologies, that these various initiatives can be better tailored to meet community needs, as community members see appropriate.

Video as a communication tool for health and wellness activities is growing in popularity among First Nations (see Martha's Story: http://media.knet.ca/node/6397; video resources on parenting at http://www.raisingthechildren.knet.ca/manual/video, among others). There are many types of videos, including those that are professionally-made and those that are user-generated.

Because video has such great potential for communication and education we asked Mishkeegogamang community members about their interest in using video for health and wellness. 94% of Mishkeegogamang community members who were interviewed reported that they would be interested in seeing videos developed to educate First Nations people on health and wellness issues.

Participants were also asked about what topic they would like to see the videos focusing on. First and foremost, participants were interested in resources on physical health and wellness, followed by videos on substance abuse and addiction, and sexuality/sexual health. In addition, community members were asked about who they would like to see "star" in these health and wellness videos. The majority (57%) preferred to see community members and people they were familiar with be featured in the videos, professionals were another choice (there can be overlap in terms of professionals and community members, like in the case of community health representatives and community telehealth coordinators), and finally 7% were interested in seeing celebrities or well-known individuals present the information.

5.8 ICT for Education

A variety of educational programs offered to Mishkeegogamang community members take full advantage of ICT in their curricula. The Keewaytinook Internet High School (KiHS - http://www.kihs.knet.ca/drupal/) is the first internet high school to be approved by the Ontario Ministry of Education.

KiHS allows community members to obtain high school credits and an education while remaining on-reserve. Tammy and Lorne, KiHS teachers in Mishkeegogamang, were happy to discuss the role of ICT n KiHS programs. They explained how students enrolled in KiHS can come to the Mishkeegogamang classroom and work on their lessons using the available workspace, computers, and internet.

Often students will have teachers who are located in other communities, therefore the local Mishkeegogamang classroom, staffed with KiHS teachers and valuable support workers and other staff (e.g., Daisy Munroe and Blair Fowler), is an important and useful resource that can facilitate increased supervision and learning. For instance, Blair works under the Transitional Program which gives him the opportunity to work with students who are in the process of transitioning into one of the educational programs and in need of "brushing up" on certain skills.

KiHS classrooms are located in twelve First Nations communities in Northern Ontario. At least once a month the various classrooms and students unite through videoconferencing. The internet is obviously an integral component of KiHS, allowing for connections between students and teachers, while also serving as the primary resource for critical information-seeking.

Wahsa (http://www.nnec.on.ca/wahsa), harnessing the power of the radio, has provided secondary education to First Nations in the Sioux Lookout zone since 1991. When compared to KiHS, Wahsa offers more independent learning which can be appreciated in any setting, especially in the comfort of your own home. Wahsa has been touted as the first high school program to address "drop-out" rates, offering the first and original on-reserve educational program. Wahsa has programming for individuals of all ages, and it is open to everyone. When a student is enrolled in Wahsa, books come through mail delivery and completed lessons are returned to urban centers (e.g., Sioux Lookout). Students typically complete approximately twenty lessons per unit, and testing can be completed at home.

Mishkeegogamang community members enjoy the independence and flexibility afforded by these educational programs. For example, Tanya Bottle has enjoyed experiencing multiple learning environments, including KiHS, Wahsa, and PLAR (Prior Learning Assessment and Recognition).

Tanya explained how she appreciated the flexible learning pace associated with Wahsa: she could choose to approach a unit at whatever pace was best suited to her own learning, tackling projects at a faster pace than typically available in a classroom environment.

5.9 ICT for Administration And Work

As a receptionist and frontline worker at the band office, Tanya Bottle uses technology for all kinds of activities on a daily basis. Tanya said that she could not imagine doing her job without the fax machine or the computer! She also noted that if her community had cell phone coverage, it would greatly facilitate contacting Band Council Members and staying in touch with community members.

Tanya is not alone in her interest in having cell phone service in Mishkeegogamang. In fact, 76% of the community members in the study stated that if their community had cell phone service, they would use it. Despite the fact that there is currently no coverage, 53% of the participants still had a cell phone, which they used when visiting larger centers with cell service, such as Sioux Lookout.

Many Mishkeegogamang community members reported using ICT for administrative and work purposes. 59% of the sample reported creating documents using a computer on a daily basis - and this increases to 77% when we include those who are creating documents on a weekly basis. Only 6% of those interviewed reported "never" creating documents using a computer.

Community members were also asked about how frequently they use a computer in an e-centre or other office in the community (e.g., health centre if they are employed there): 46% reported using a computer in an office in the community on a daily basis; and this increases to 64% when looking at regular use (weekly or more often). It is evident that the internet and websites have become a prominent resource for information: 88% of those interviewed reported reading information on a website on a regular basis. Not one participant indicated "never" having read information on a website.

5.10 Youth and ICT

While in Mishkeegogamang in September of 2010, a First Nations Innovation researcher had the privilege of visiting the Grade 7 and Grade 8 class at the Missabay Community School. Crystal, the community telehealth coordinator, accompanied the First Nations Innovation researcher on the visit. Since the previous community member interviews had only been with adults, the two class visitors were curious to learn about how the youth were using technology in their daily lives.

The youth were excited to talk about their technology use and compare their use with that of the adults' in our sample. Interestingly, the students even developed their own chart of technology use, noting how often they have used a broad range of technologies, including (but not limited to) email, radio, and online video. Perhaps it is no surprise that the youth were convinced that they were using technology more frequently!

Videoconferencing is one technology that the youth are still becoming acquainted with: a project using videoconferencing to connect the Missabay class with other classes in Africa and other countries was planned for 2011.

During the community interviews, certain participants discussed the use of ICT by youth. Several participants recognized that the youth in Mishkeegogamang were very engaged with the technology, and often more so than the adults. These quotes demonstrate how ICT can be used by youth in a positive way, while at the same time highlighting the importance of responsible and respectful use of ICT..

"We need to gain some kind of control as to what our kids are doing on the internet, especially if they're going to be disrespecting one another. That's the only concern I do have with the technology that is being created, especially the internet. But other than that, if they were taught to use it properly, I think it would be a very useful tool for them, to develop their own projects for school or whatever."

--Mishkeegogamang community member

"I have a nine-year-old who is really interested...…and she is actually showing me how to edit and make a little video. I don't know how to do my own video, so yeah, that's pretty neat. I talked to her about respecting and like only certain things should be put on video, not to make fun of people."

--Mishkeegogamang community member

5.11 Creative Purposes

During the spring 2010 First Nations Innovation visit, the community hosted a video festival to raise awareness about local talent and creativity. The video festival was offered at a few different venues, including the KIHS classroom, the Missabay community school, and the Resource Centre. Videos featured were made by different individuals from First Nations across the Sioux Lookout Zone.

There were even a couple of videos from Mishkeegogamang. The photo above is a screenshot from a YouTube video that was included in the community video festival. This video was of children at the Missabay Community school who were singing a song they had collaborated on called "Love, Love, Love." Many community members and interview participants reported an interest in seeing more videos created by members of Mishkeegogamang and they recognized that there was some very exciting talent and creativity within their community.

When the community members were surveyed, 65% reported wanting to see fellow community members creating traditional videos. Another 14% were interested in seeing videos focused on different issues and activities within the community. The three quotes below demonstrate the strong interest in traditional videos.

"More traditional stuff, you know, to do with traditions around this community because every community has its own traditions that they observe. I mean, I've been here for a long time, but to know specifically those kinds of cultural things, I think would be good. And it also exposes the ... the younger ones to that because ...…they're the up and coming generation ... this is what they're going to be left with basically."

-- Mishkeegogamang community member

"One of the videos that really stood out for me was the one where that young boy wrote about a girl who was being abused and his song...…There was two videos where there was a traditional (dancer) and you see the kids just being captured like that. And we actually got back over and there were some kids outside dancing. So that kind of tells me that in the next few weeks we have to bring in some dancers and so we're going to bring in different types of dancers to the community."

-- Mishkeegogamang community member

"More traditional videos, I guess, on parenting. Probably like a bunch of elders can get together and to do a video on parenting the traditional way."

-- Mishkeegogamang community member

Many individuals are already engaged with using various ICT for creative purposes, like creating videos. For example, all of the community members surveyed reported using cameras to take pictures; 41% of the sample engages with creative picture-taking on a regular basis. Further, 8% of the sample reported creating videos yearly.

This number will likely grow quickly, as many individuals reported that even though they weren't creating videos at the time of the interview, they had a strong interest in creating them in the near future. In addition, the community and First Nations Innovation hosted a video training workshop in the spring of 2010, led by Cal Kenny (K-Net's multimedia producer), and the community's KIHS students are involved in a video creation activity.

5.12 The Future: Virtual Visits

During the interviews, participants were asked whether they would be interested in having "virtual visits" with people in their own community, in other First Nations in the Sioux Lookout zone, and with those even further away (e.g., Thunder Bay or other locations across the world). Participants were asked to imagine that these video/virtual visits were easy to do, and free.

Participants were very interested in having this type of connection. 92% of participants were interested in the idea of having virtual visits with people who lived in different areas across Canada and the world, 72% were interested in having virtual visits with people living in First Nations communities in the Sioux Lookout zone, and 62% were interested in virtual visits with other Mishkeegogamang community members.

Geographical closeness was one reason that was commonly cited for the lack of interest in having virtual visits with local community members. Nevertheless, some individuals saw potential uses in virtual visits between community members. For instance, the community is spread across many kilometers, meaning that it is sometimes difficult for community members to connect and attend certain events if they are separated by such a distance and do not have the means to travel. One participant thought that virtual visits would be ideal in the educational milieu, and that they could be very useful in terms of connecting teachers with parents.

"It'd be great for parent/teacher interviews and anything like that, like people that couldn't make it, that'd be really good. Oh yes, that'd be great."

-Mishkeegogamang community member

6. Challenges and Needs Related to ICT

In order to facilitate the positive engagement of Mishkeegogamang community members with these various information and communication technologies, certain challenges and concerns need to be addressed in order to support effective use of ICT (Gurstein, 2003).

Training

Training of community members on a continuous basis, focusing on honing skills, encouraging the adaptation of ICT to community needs and interests (instead of simply following mainstream use), and supporting critical thinking about ICT, could contribute to the sustainability of effective ICT use within Mishkeegogamang. Community technology champions could be engaged in this venture, and enlarging the circle of potential trainers would be important. Several community members are already knowledgeable in creating and editing videos (having been trained during the video training workshop offered by Cal Kenny, the Multimedia specialist at KO/K-Net, and having previous experience/training as well) and they would serve as a great team for educating and collaborating with other interested community members who have stories they wish to tell and share.

Adapting ICT to Community Needs and Concerns

Throughout the community interviews, the theme of concern around positive and healthy use of ICT was apparent. Community members often reported excitement and interest in using ICT, while at the same time expressing some concern over damaging or negative uses of ICT (e.g., gossip and cyber-bullying on Facebook). As a community, it will be imperative to collaboratively encourage respectful and safe interactions on social networking sites, and on the internet in general. For example, when individuals are using media to share their creative work, including such things as videos and traditional stories, it is important to be able to share such resources and knowledge within a respectful environment. Negativity and disrespect will only hinder participation and engagement.

In order to engage with ICT in a healthy and enjoyable way, it is important to have a good understanding of the advantages and disadvantages of using different types of ICT. For example, some community members have reportedly expressed some concerns around Google Earth and invasions of privacy,; others are curious about who might have access to their telemedicine session.

These are important and valid concerns and in order to promote positive engagement with ICT, questions like these need to be addressed, and critical thinking around using ICT needs to be encouraged. Fortunately, there are technology champions within the community who could work with community members to answer questions like these. For example, the Community Telehealth Coordinator has knowledge of the process of videoconferencing and telemedicine and can answer any questions around confidentiality.

Also, some interview participants commented on the importance of using ICT in a balanced way. Many technologies can facilitate and compliment active lifestyles and positive community events (e.g., GPS while out on the land, videos of traditional activities, using the radio station to facilitate community dances, video festivals, etc.), as opposed to simply contributing to sedentary problems.

Finally, most ICT and accompanying software are based on the English language. Despite the fact that the majority of community members speak English, preserving their traditional language is of utmost importance. The community radio station connects with its audience in both languages: perhaps the respect that the radio station shows to the Ojibway language helps explain why it is one of the most embraced technologies in Mishkeegogamang. Video-making can also help capture and preserve traditional language and practices at the same time: interview participants were quick to notice the potential that exists there.

Financial Support

The ICT services that are offered in the community are associated with costs, even though many programs are funded, some integral programs are at risk of discontinuation because of a lack of financial resources. The Elder visitation videoconferences require a budget allowance for the traditional food that is offered to the participating elders. As of recently, the organizers have had challenges finding the resources and support that is required to provide lunches to the participants. This is unfortunate in light of the success and excitement that surrounds this event. In the future, key "stakeholders" could brainstorm and collaborate on ways to address this issue in order to ensure a continuation of this excellent program. In addition, continued community involvement in determining what educational sessions to offer via telehealth would be beneficial.

Limitations of the ICT Infrastructure

One challenge facing the community is generating ongoing funds to make the community network and infrastructure sustainable. The initial community connection was built 100% by public funds; however there is no funding for ongoing support and maintenance of the network. In certain other First Nation communities, once the infrastructure was in place the community took over the network to run it as a community business, supported by the community network users. However this model was not adopted in Mishkeegogamang. The subscriber units were installed when people asked for them, and a small installation fee was charged but there was no process in place for subscribers to pay for ongoing costs; those living close enough to a tower just used the service. The result is that so many people are using the network that the bandwidth is often fully used and there are often problems getting an internet connection. So for example, when some people are sharing files, downloading music and watching videos, the health centre may not be able to access enough bandwidth to do health administration on the network.

Because the community is not currently collecting funds for the network, there is no money available to perform the necessary maintenance and upgrades to the network. The community Wi-Fi points needing replacement will not be serviced until somehow funds become available to upgrade the network. The result is that everyone in the community wants and needs the internet but they do not have high-speed or reliable service because the infrastructure is overloaded and slow. Currently, repairs and upgrades are made on an ad-hoc basis.

As KiHS relies on the internet for its infrastructure, the Mishkeegogamang classroom could benefit from a stronger and faster internet connection. In fact, it is likely that the entire community of Mishkeegogamang could benefit from this, as the current state of the infrastructure makes it difficult to engage in some activities that require large amounts of bandwidth - like uploading videos, for example.

Mobile Infrastructure

Currently, the community of Mishkeegogamang does not have cell phone coverage. Overall, there appears to be a fair amount of ambivalence concerning whether the community would benefit from cell phone service. Some community members who were interviewed reported that they were concerned about the decrease in privacy and personal time that could result, while others were clearly interested in obtaining cell phone coverage. Seventy-six per cent of the sample stated that they would use the cell phone service if it was available. It could be helpful to explore this possibility further, in addition to seeking out more feedback from community members, and other First Nations who have introduced mobile service to their community (e.g., Fort Severn First Nation and Keewaytinook Mobile).

7. Discussion and Conclusions

The community members of Mishkeegogamang use a wide range of interactive and robust technologies as tools for a variety of activities. Community members communicate and stay informed on important issues via a blend of "older" and "newer" technologies. These include the community radio and community newsletter, as well as the community website, and social networking sites. All (100%) of community members interviewed reported using a landline telephone daily, and this is only slightly more than those who use email on a regular basis. Among community interview participants and those profiled, exciting ideas of how to use ICT as tools in goals of health, wellness, and education were explored. In addition, the use of technology to support traditional and land-based activities also intrigued community members. Several individuals reported an interest in having traditional knowledge and meaningful teachings preserved and archived through video.

The information discussed in this paper presents possible ways forward for continuing to engage with technology in positive ways, and for creating and sustaining an environment that facilitates that. For example, there is interesting potential for projects that unite elders and youth, like using ICT (e.g., video) to record elders' stories and important teachings. There was also interest in continuing to keep the Mishkeegogamang website updated, and making it more of an interactive sharing space for community members (e.g., conceptualizing the website as more of a portal).

It will be important to continue to learn and engage with community members about technology use. The community interviews that were completed for this study were only with 17 community members, all of whom were adults. It would be interesting to engage in a discussion with more community members (especially youth!) to learn what the concerns are, and how a positive environment for ICT engagement can be better supported.

Also, how can technology use be better supported in the community - for example, a community member may want to try videoconferencing but may lack the training (this is often the case for first time videoconference users, because in many organizations training is not available or offered on a regular basis). A knowledgeable community member, like one of the Community Telehealth Coordinators or any community member who has videoconference experience, could become a technology mentor. Excited and interested older students who are learning about new technologies (like videoconferencing) can also be involved in connecting with other schools and communities, as well as introducing their family members or other community members to the benefits of certain technologies.

In conclusion, it is evident that there are many talented and passionate individuals in Mishkeegogamang! We hope that community members will continue to enjoy and benefit from using ICT as support tools for community and individual development, across many different domains.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research team would like to thank Mishkeegogamang First Nation Chief Connie Gray-McKay for inviting us into her community and making it possible for First Nations Innovation to conduct outreach and research activities with the community. We would like to thank Erin Bottle for being our community liaison, and Darlene Panacheese and Crystal Kakekayskung for being our "tour guides" around the community. We would also like to thank Heather Coulson of Keewaytinook Okimakinak for acting as a liaison during our visits. We also acknowledge the work of NRC Analyst Betty Daniels who performed data entry and analysis for this project. Furthermore, we appreciate the information and knowledge that Brian Beaton and Jamie Ray of KO/K-Net shared with us in helping develop a section of this paper. In addition, we value the feedback that members of the First Nations Innovation project gave on this paper and the overall project.

Finally, a warm thank-you to all the community members who participated in the interviews and the community discussions, and to those who volunteered to be "profiled" in this paper: you made us feel welcome as visitors to your community and we are learning from your ideas, stories and experiences. We have great memories of our visits, and for all of this we are sincerely grateful.

This research was conducted as part of the First Nations Innovation project: http://fn-innovation-pn.com funded by in-kind contributions from the partners - Keewaytinook Okimakanak, the First Nations Education Council, Atlantic Canada's First Nation Help Desk and the University of New Brunswick - and by grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).