The Cancellation of the Community Access Program and the Digital Divide(s) in Canada: Lessons Learned and Future Prospects

Masters Student, School of Library Archival and Information Studies, University of British Columbia, Canada. Email: CDLBlanton@netscape.net

INTRODUCTION

The term digital divide has many definitions (Gurstein, 2003), but generally refers to a persistent inequality between groups of individuals in their ability to participate in society through the medium of information and communication technologies (ICT). The term can have a broad or narrow scope; it can be used to refer to a lack of access to the Internet or to a lack of ability or willingness to use digital information technology (van Dijk and Hacker, 2003). Discussions of the digital divide in Canada have encompassed "issues of technology access and affordability, technology as a primary means of individual or community development, geographical access, and constructions of different types of community (virtual, interest, geographic, and the technology infrastructure of communities)" (Rideout and Reddick, 2005).

In April 2012, the Government of Canada officially ended its Community Access Program (CAP), Canada's longest running government initiative to close these divides. CAP was a federal program that provided grants for Internet access and training in remote, rural, and underprivileged communities ("Ottawa cuts CAP", 2012). Cancellation of the program removed a major source of funding from thousands of access sites across Canada, throwing into doubt the future of the community networking projects that they support.

This paper begins with a description and history of CAP, including the events leading up to its cancellation, and then evaluates the government's claim that the program is no longer needed, looks at the effect that its cancellation will have on the organizations that operate CAP sites, and concludes with a look at the future of public Internet access in Canada, considered both as a question of national Internet policy and from the perspective of Community Informatics and First Mile approaches to addressing the digital divides.

CAP: A BRIEF HISTORY1

CAP has contributed to bringing computer and Internet technologies to Canadians across this country, and has successfully achieved its objectives. In these challenging times, the Government remains committed to prioritizing expenditures and returning to budget balance. CAP was scheduled to end March 31, 2012, and will not be renewed.

- Letter from Lisa Setlakwe, Director General of the Regional Operations Sector of Industry Canada, posted on-line by CBC News ("Ottawa cuts CAP public web access funding", 2012).

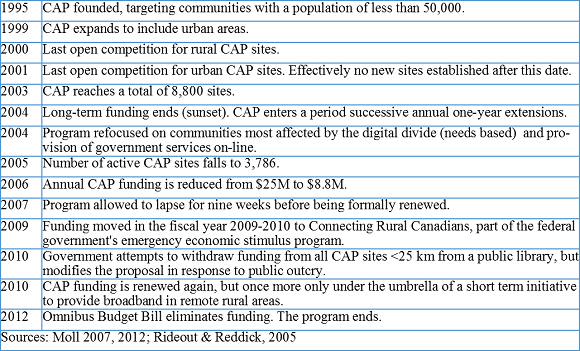

The Community Access Program (CAP) was launched in 1995 under the auspices of the Canadian ministry of industry (Industry Canada). CAP was one of a number of programs in the Canadian government's Connecting Canadians initiative, whose agenda was to make available access to the Internet, and thus, to the developing information-based economy, for people and places that would not be likely to get such access through market-based solutions.2 CAP attempted to meet this goal by providing funding for access sites operated by partner organizations (grant recipients) in schools, libraries, community centres, friendship centres (non-profit community institutions providing services to aboriginal peoples, especially in towns or urban areas), and other social service centres (Moll, 2012). The CAP grants provided money to the host organization for computers, Internet connectivity, and ICT training (Rideout & Reddick, 2005). Typically an access site would consist of a small number of Internet-connected computers, serving as public access terminals, with associated peripherals such as printers, and sometimes with stand-alone software such as word processing or spreadsheet management programs. In many cases, the hosting organization would provide some level of technical support and computer training to the users of the access terminals. A companion program, the CAP Youth Initiative (CAP-YI), provides funding to young interns to work at CAP sites.

Initially, CAP grants were intended for communities with a population of 50,000 or less, reflecting a concern that rural and remote areas of the country were being missed in the initial build-out of the Internet in Canada. Four years later, the program was expanded to include urban areas (Rideout & Reddick, 2005), to address fears that economically or socially disadvantaged urban dwellers were at risk of being left behind as well. The initial goal of CAP was to have 10,000 access sites in place and operating by 2001. This target was never met (the greatest number of operational sites was 8,800, achieved in 2003). Subsequently, the Liberal Party promised in its 1997 platform to connect all rural communities with populations of 400-50,000 to the Internet by 2000.

The years 1999-2004 could be considered "the golden age of connectivity policy in Canada" (Moll, 2012). The government of the day envisioned the program moving beyond simple network access and infrastructure for economic development to encompass a broadly defined objective of connectivity as a vehicle for social cohesion, with the program's vision, policy, and financial support all aligned to this objective.

2004, however, marked a significant turning point in the fortunes of CAP. The original program was scheduled to end in March of that year. The Liberal government of Paul Martin (who succeeded Jean Chrétien as prime minister in 2003) renewed CAP for a term of only one year, beginning a period of successive annual extensions that left CAP's community partners in a perpetual state of suspense about the security of their funding from year to year. At the same time, the focus of the program was narrowed from broad society-building goals to a two-fold objective of promoting Internet access in the neediest communities, and of delivering government services on-line.

As the minority Liberal government of Paul Martin was succeeded by the minority Conservative government of Stephen Harper, CAP continued to be scaled back. In 2006 its funding was cut by 65%, in 2007 its funding was allowed to lapse completely for nine weeks before being reinstated, and in 2010 the minister of the day attempted to impose provisions that would close all CAP sites that were within 25 km of a public library (a decision that was eventually reversed in response to public protests). By 2001, Industry Canada was no longer accepting applications for new CAP sites, and after a decade of funding cuts and narrowing terms of reference, the number of active sites had fallen from a probable high of 8,800 to one or two thousand by program's end.3

CAP has been open to criticism for being at times too narrowly focused on technical access, computers and connections, at the expense of addressing human and social needs. This limitation seems in part to be a natural consequence of being administered by Industry Canada and therefore heavily influenced by Industry Canada's departmental mandate.4 It is also in part the result of logistical considerations (it is easier to deal with a few thousand access sites as opposed to the individual needs of several million end users). The funding model is sometimes criticized for not providing large enough follow-up grants to match the initial start-up grants, leading to sustainability problems. The program also experimented with requirements to provide Canadian content on-line, which proved to be a distraction from the program's core objectives and went beyond the competency of Industry Canada to administer (Rideout & Reddick, 2005). CAP also struggled to adapt its original program, tailored for serving rural and remote areas, to Canada's cities: in particular, it was difficult to identify "communities" within the urban context that were willing to serve as partners and champions for CAP sites, a challenge which led to problems with long-term sustainability (Gurstein 2007, note 41). On balance, however, CAP has proven highly successful at meeting its objectives of increasing the capacity of local communities to access and share information online (Moll, 2007a, 2007b).

THE DIGITAL DIVIDE: MISSION ACCOMPLISHED?

According to Industry Canada, the government cancelled CAP because it had met its objective to make Internet broadly accessible. CAP launched in an age when only 10 per cent of Canadian households had Internet service at home. As of 2010, that proportion had grown to 79 per cent (Holmen, 2012). The Canadian federal budget of 2012 noted that 94% of Canadians lived in an area where broadband Internet access was available for purchase, and claimed the program had "outlived its usefulness" (Freeman, 2012).

Government Members of Parliament responded to constituents upset at the cancellation by repeating the government's talking points, and some even went further. When questioned whether low-income people would lose Internet-access as a result of the government's decision, Okanagan-Shuswap MP Colin Mayes responded: "Life is about priorities and you have to set those priorities and decide what's important to you. People always find the resources to find what's high on their priorities, whether they're poor or not. Those are the decisions you have to make in life, whether you're poor or not" (Wickett, 2012).5

The most-cited source of information on the Internet access divide in Canada is Statistics Canada's Canadian Internet Use Survey (CIUS). The 2010 iteration of this survey found that 79% of Canadian households6 have Internet service. Of the remaining households, 56% said that they did not have Internet access because they had no need or interest in it. Over time, surveys of Internet use in Canada consistently identify a category of "core non-users" who have not used the Internet and have no intention of doing so in the future (for example, in 2003, core non-users made up 60% of all Canadian non-users) (Rideout & Reddick, 2005). Thus, after factoring out the core non-users, the latest Stats Can figures suggest that approximately 12% of Canadian households would like to use the Internet at home, but can't, whether because of the cost of the service or access equipment (20% of non users), lack of a device that can be connected to the Internet (15%), or a lack of skills, knowledge, or confidence (12%).7 Local unavailability of Internet access was not frequently mentioned as a cause for non-use, which is consistent with Middleton & Sorensen's (2006) finding that "for most Canadians, home Internet access, if they want it, is available on a commercial basis."8

These aggregate figures, however, conceal some significant inequalities related to income, age, education, and geography. The most glaring divide was along the lines of income: 97% of households in the top income quartile had access, compared to 54% in the lowest quartile (corresponding to incomes of $30,000 or less). People who live alone are much less likely to have Internet access than households with three or more people (58% compared to 93%). Three provinces had household access levels of 73% or less; New Brunswick's level was 70%. The CIUS completely excludes the territories (Yukon, NWT, Nunavut), who almost certainly would have much lower than average rates of access. McKeown, Brocca & Greenhof (2010) found a significant disparity in Internet access and usage between urban and rural areas in the CIUS data for the years 2005, 2007, and 2009, particularly in the availability of high-speed access. This gap showed signs of narrowing somewhat over time; nevertheless, only 54% of residents of small communities reported having used a high-speed connection during 2009, as compared to 76% of Canadians living in communities with a population of 10,000 or more. Although the Internet has experienced a rapid rate of diffusion in Canada compared with earlier technologies (McKeown et al, 2010) and is becoming more equitably distributed over time (Howard et al., 2010), statistics show that reliable broadband access remains elusive in rural and remote communities (McMahon et al., 2011), and for the poorest citizens, residential access of any sort remains an unaffordable luxury.

The government's claim that the Community Access Program is no longer needed is also belied by direct observations of use of public access terminals in communities across the country. Longitudinal research shows that between 1997 and 2005 use of public Internet access sites held constant, with site users constituting roughly 7% of all Internet users and 15% of low-income Internet users (Rideout & Reddick, 2005).

In the city of Victoria (British Columbia), the manager of public service told reporters that the library has seen no indication that the demand for free public access is going down, despite the increasing availability and up-take of residential Internet access described in the nation-wide surveys. The computer stations are well used and often have a queue; a wide cross-section of people use them, including those of limited means, students, and seniors without the knowledge to set up a home computer (Holmen, 2012). In Smithers (BC), where CAP funding for library-based public access began in 2005, use of the public terminals increased 43% between 2005 and 2012, exceeding 9,000 accesses per year in the last year data was available (Hudson, 2012). In the 12 member libraries of Alberta's Shortgrass Library system, 37,500 users accessed the Internet for a total of about 54,000 hours in 2011 (Quinlan, 2012).

CAP has also been instrumental in bringing Internet access to remote and rural communities. In northwestern British Columbia, CAP funding brought Internet into isolated settlements and provided for public terminals in First Nations band council buildings. The community of Una River used a CAP grant to deploy a community Wi-Fi network, and other recipients used CAP money to pay for secondary radio towers to boost their Internet speeds (Hudson 2012). In both Ontario and British Columbia, rural library-based CAP sites are regularly used by members of Mennonite or Hutterite colonies (faith-based communal settlements with limited contact to the outside world): in Eastern Ontario colony members use CAP terminals to register births (Newman, 2012); in Alberta, many of these Low German speakers do not have broadband Internet access in their colonies and for them the public terminals offered by the regional library system are their primary point of contact with the English-speaking world (Quinlan, 2012).

To sum up, then, the aggregate statistics, adduced by the government and its supporters as evidence that CAP is no longer needed, in fact hide significant residual gaps in Internet access along lines of wealth, age, education, and geography, with poverty being the single greatest predictor of exclusion from the "information society." Even if the objective of the Community Access Program is narrowly defined as elimination of the access divide, it is clear from the evidence that CAP has far from outlived its relevance, and that if withdrawal of CAP funds leads to the closure of CAP sites, many of their neediest users will face hardship or be cut off from the Internet altogether.

RESPONSES TO THE END OF CAP

What happens if sustainability funding is impossible to achieve at the community level? What will happen to the connected communities if long term sustainable government funding does not occur? What will happen to communities that have to unplug? - Vanda Rideout, 2002

Given the diversity of organizations that operate CAP sites, it is not surprising that the closure of the program affects them in different ways, nor that they differ widely in their strategies (and capabilities) for responding to the loss of CAP funding.

For some large urban and regional library systems that operate CAP sites, the 2012 announcement was something of a non-event. For example, both the Hamilton (ON) Public Library and the Vancouver Island Regional Library (BC) had been expecting the cancellation of the program and prepared contingency plans. Hamilton reallocated funds from its computer training budget to keep public access terminals open ("Funding loss won't hurt library program", 2012). The VI Regional Library absorbed the loss of nearly $95,000 per year in CAP funding from within its existing budget and promised local communities on the Island that they would see no changes in service at its branches (Miles, 2012). At the other extreme, the public library in Guelph (ON) seemed entirely unprepared for the program's cancellation; a spokesman for the library predicted the loss of the program would impair the library's ability to provide services and could offer no plan for dealing with the situation other than "let's hope [the computers] don't break." ("Library fears losing free Internet access", 2012; O'Flanagan, 2012).9

Some mid-sized libraries also planned to juggle their budgets to protect services at the access sites, such as the Okanagan Regional Library, which stood to lose approximately $4,000 per year per branch. The system's executive director promised that the libraries would continue to offer public Internet access, but warned that the cuts would have a ripple effect throughout the system, affecting other departments and services (Wickett, 2012).

For recipient organizations that used the CAP funding for capital expenses and software upgrades, rather than operating expenses such as ISP fees, the loss of the grant money was not expected to have an immediate effect, but still placed the long-term viability of the access sites into question. Even the Victoria Public Library system, which reassured patrons that it considered public Internet access to be a core service and would absorb the $26,000 short-fall into its operating budget, also said that it planned to reduce the frequency of computer upgrades (Holmen, 2012). The public library in Kitimat (BC) used its CAP funds to pay for hardware and software upgrades and maintenance, not operations, and therefore expected no impact to services in the next 18 months. For the longer term, it was hoping to turn to the Friends of the Library to raise the $5,000-$6,000 necessary to replace the CAP grants (Orr, 2012). In Pictou County (NS), libraries will continue to offer public access terminals but services will be scaled back: hardware and software upgrades will be less frequent and training will not be available ("Feds cut CAP site funding," 2012).

The smallest public libraries, especially stand-alone libraries in small rural communities, have the fewest resources to respond to the loss of the CAP funding. In Norwood (ON) the Asphodel-Norwood Public Library continued access for the current budget year by dipping into Library reserves. Municipal officials suggested that the library look into cutting other services to redirect funds to Internet access, and debated the wisdom of imposing a small access fee (Freeman, 2012). The Burns Lake (BC) Public Library immediately announced that it might have to stop providing free Internet access unless either the Village of Burns Lake or the Regional District of Bulkley Nechako could provide replacement funding. Alternatively, it warned, it might consider charging for Internet access (Billard, 2012). In Eastern Ontario, the Whitewater Region Public Library had been receiving $10,500 for its 3 branches. At least one branch is downgrading to a slower Internet service, despite heavy use by the kayaking and tourist communities. The regional library will be forced to choose between buying books and maintaining Internet access, but will try to resort to fund-raising to close the gap (Newman & Mercury, 2012).

In recent years, many community centres have lost their CAP grants as the Industry Canada has preferentially directed funding towards public libraries (Moll, 2012). The remaining access sites located in community organizations are especially vulnerable to the loss of federal grant money. Many of these relied on CAP funding for day-to-day operations and had to scale back services immediately or shut down their public terminals altogether. In Pictou County (NS), sites located in community centres were expected to close ("Feds cut CAP site funding", 2012). In Salmon Arm (BC), the Downtown Activity Centre offered two public-access terminals to at-risk youth, which they use for applying for jobs, child-care subsidies and income assistance, for doing job searches, and preparing resumes. The centre plans to continue to provide some sort of access, but it may not be able to serve all of its current clients (Wickett, 2012). CEED, an organization in Maple Ridge (BC) dedicated to sustainability, provides public Internet access terminals for government service access, resume writing, and job searches. It now is using money from fund-raising events to maintain the service (Rantanen, 2012).

On a larger scale, the government of Nunavut has recognized the value of the public access sites in the territory's small, widely scattered, and generally isolated settlements through its immediate intervention to replace the entire $85,000/year in CAP funding received by the territory with funding from the territorial Department of Education ("Nunavut takes over community Internet access funding", 2012). To date, there has been no general movement on the part of other senior governments across Canada to follow Nunavut's example.

POLICIES AND ALTERNATIVES: THE FUTURE AFTER CAP

Up to now, the fate of access sites that lose CAP funding has tended not to be good. Rideout and Reddick (2005) documented the closure of 1,200 sites roughly around the same time long-term secure funding for the program was withdrawn in 2004. The same authors received anecdotal evidence following the conclusion of their formal study to suggest that a further 1,000 sites had to close because of a loss of CAP funding. By 2005, the number of funded CAP sites had dropped to 3,768. There is circumstantial evidence to suggest that a significant proportion of the sites de-funded in the decade of 2000-2010 completely ceased operations.10 If most CAP sites are not viable without government funding, and given that there are still millions of Canadians who depend on these sites for Internet access, what alternatives will these users have in the future? And what options does Canada have for a post-CAP national policy on Internet access?

In the wake of the cancellation of CAP, Industry Canada suggested that users of former CAP sites who needed to access e-government services (such as Employment Insurance claims and benefits) could use public terminals at Service Canada locations. This option seems impractical in communities such as Guelph, Ontario, where the public library CAP sites serve on average 300 people a day, of which 40% are job seekers. There is only one Service Canada location in Guelph and it is only open between 8:30 a.m. and 4:30 p.m (O'Flanagan, 2012). Although comprehensive research on the subject is not available, it seems improbable that public terminals in federal and provincial government offices could accommodate all of the people Canada-wide who currently use CAP sites to access government services.

It also seems unlikely that the private-sector will step in to replace CAP sites with commercially operated telecentres (e.g., cybercafés, Internet cafés, or pay-per-use Internet terminals). In a few cases, most notably in popular tourist destinations, cybercafes and similar businesses may offer an option, but even where they are present, cybercafes do not provide the same services as community access sites.

A community access site is rarely just a place for access. Activities, services, and programs are in support of community activities; access is obtained in a context of broader social or economic goals or activities, which are communal and not just individual, and the site is designed, staffed, and equipped specifically with these goals in mind (Gurstein, 2007).

For new computer users and those lacking in computer skills, the training, mentoring, and technical support services offered at even the most basic of community access sites will typically not be available at a cybercafe. Also, the access revolution provided by nearly ubiquitous public Wi-Fi has ironically been a step backwards for the poorest Canadians. Much of the commercial public-access Internet in Canada now requires users to provide their own devices. Those who cannot afford home Internet access (or a permanent residence to connect it to) are also unlikely to afford the price of a tablet computer or a low-end laptop.

If the group most vulnerable to the loss of free, community-based telecentres are the very poorest citizens, one possible way to end a wealth-based digital divide is simply to make sure that every citizen has enough income to pay for basic services, including, if he or she wants it, Internet access. This end could be accomplished by a national income redistribution system, often called a "negative income tax" or a "guaranteed minimum income." Such approaches are used to some extent in European social democracies and experiments in North America have shown that a guaranteed minimum income could actually be more efficient than narrowly targeted and closely supervised social welfare programs (Anderson, 2010; Forget, 2010; Segal, 2008). In the case of the digital divide, the desired outcome would be that each low-income person, after paying for such necessities as shelter, food, and clothing, would have enough discretionary income to afford a computer and Internet access (if living at a fixed address), or a data-ready mobile device (if not). However, in the current political and economic climate, it seems unreasonable to expect that Canada would undertake such a dramatic change of policy regarding income redistribution, whether by a negative income tax or some other means. Furthermore, if such a program was designed simply to replace the existing social welfare programs, it is questionable whether the guaranteed income paid to disadvantaged Canadians would leave them any better equipped to pay for ICT services than they currently are today.

A simple dollar-for-dollar replacement of the former CAP grants by other levels of government is also unlikely. Most provinces already face growing public debts and struggle to fund existing priorities such as health care; given that the closure of CAP sites only affects a small percentage of the electorate, and in the case of the poorest users, those who are least likely to vote, there has been little political will for the provincial and territorial governments (with the lone exception of Nunavut) to intervene. As for local governments, the communities that stand to be harmed the most by the loss of CAP funding will tend to be ones whose revenue base is simply insufficient to support the provision of new public services. Furthermore, Rideout and Reddick (2005), citing studies from the early 2000s, have concluded that neither local governments nor corporate sponsors tend to be effective partners for not-for-profit organizations operating community access sites.

Some community organizations and small libraries have considered pay-for-service Internet access as a possible response to loss of CAP funding (Billard, 2012; Bodnar, 2007; Freeman, 2012), a model that could potentially apply to other not-for-profit telecentres as well. On the face of it, this seems contrary to the mandate of community access sites to provide access to all users, including those for whom lack of money is a primary reason for not being able to get services elsewhere. In fact, free (as in no charge) access has never been a requirement for a site to participate in the CAP. In New Brunswick, at the height of the CAP program (2001) 68% of the sites had membership fees and 64% charged course fees (Reddick, 2001). Some organizations offer a combination of free and paid access depending on the time and purpose. The Hotspot in Squamish BC, for example, tried to balance access with revenue generation: "Some groups, seniors for example, can come in for free all day, one day per week. Access is free after school for homework and job search; resumé and government online usage is always free. Outside of that, the standard charge is $1 per 30 minutes use of a computer and Internet connection" (Moll, 2007b, p.11). However, just as even small library card fees can prove a significant deterrent to library use, nominal usage charges may well deter users from using public access terminals. Perhaps public access sites in heavily frequented tourist destinations such as Whistler-Squamish could thrive on this model, but it is an open question whether other types of public access sites could attract enough paying customers to keep the lights on.11

The most likely national connectivity policy to replace CAP is an extension of the immediate response to the 2012 budget: that the federal government will continue to download responsibility, both for supporting e-government access and for addressing the remaining digital divides, onto public libraries. Given that public libraries obtain the majority of their operational funding from towns, cities, and regional governments, the result is a significant transfer of responsibility from the national to the municipal level. Some libraries, such as the Greater Victoria Public Library, explicitly acknowledge public Internet access as one of their core services and have allocated resources to provide it. Patron pressure will likely force most libraries that can afford it to take this approach, even if it requires cutting back in other departments to free up the required funds.

Whether the public access terminals and Wi-Fi access are paid for from the library's core funding or are supplemented with fund-raising from the community and grants from donors, it will generally be the large city libraries and major regional district libraries that have the resources to take on this mission. Smaller library systems and their users across Canada won't be as lucky (Wicket, 2012, quoting a report by Hamilton Public Library head librarian Ken Roberts). As the executive director of Okanagan Regional Library System put it, "It's the little stand-alone places-like Radium Hot Springs, Midway or Grand Forks-[that will suffer]." ("Funding loss won't hurt library program", 2012). Consequently the greatest impact nation-wide of the loss of the Community Access Program will not be found in the divide between the rich and the poor (although that divide will continue to exist and will doubtlessly worsen to some extent) but in the divide based on place and local economics, with the key factor being a community's ability and willingness to support a healthy public library system.

CAP AND WHAT COMES NEXT: A COMMUNITY INFORMATICS PERSPECTIVE

The federal Community Access Program is not in itself an application of community informatics; indeed it is a classic example of the type of top-down program typically run by a large government department, complete with all manner of administrative controls and restrictions, intended to provide accountability but in practice limiting the ability of recipient organization to meet local needs and adapt to local conditions (Gurstein, 2007). On the other hand, CAP funding has been a key enabler for community informatics projects, such as a Wi-Fi network to serve isolated older men living in a low-income Toronto neighbourhood (Moll, 2007b), or a community networking centre that offers volunteering opportunities to new immigrants who are having difficulties breaking into the Canadian job market (Dechief, 2012). It is not surprising that CI practitioners have had something of a love-hate relationship with CAP, some praising it on the one hand as "a little-known national success story" (Moll, 2007a, para. 1), others decrying its "very limited success ... and very great difficulty in achieving any degree of local sustainability" (Gurstein, 2007, p. 58).

From the perspective of community informatics, then, the "golden age" of community networking in Canada may not have been the height of the CAP program around the turn of the millennium (as suggested by Moll, 2012), but the early 1990s, when local activists were setting up the "free-nets" and telecommunity networks that gave ordinary Canadians their first opportunity to connect to the Internet. By the end of the decade, the increasing replacement of dial-up access with broadband service and the ubiquity of nominally free e-mail services such as Hotmail and gMail led to a general decline of these community-owned and funded facilities (Bodnar, 2007). For many community organizations, accepting CAP funding became something of a devil's bargain: they gave away much of their autonomy and became dependent on federal grants, which, after 2004, had to be renewed year-to-year. Still, the years of the CAP program could at least be called a "silver age" in which federal funding allowed local organizations to continue to provide access to disadvantaged and underserved Canadians and to experiment with new ICTs on a community level.

With the withdrawal of CAP funds, the application of community informatics in Canada appears to be entering a third age, the exact nature of which has yet to become clear. Clearly there is still a need for public access sites: if they were all to vanish overnight, as many as 10% of all Canadians and nearly 50% of the poorest people in the country would be cut off from what has become a prerequisite to full participation in the modern Canadian economy and civil society.12

Rideout and Reddick argue that the not-for-profit organizations that operate public access sites are delivering community and government services to citizens such as education, skills training, literacy training, and health information and services. As these are public services offered for the public good, they should be supported by public funds, which means support from federal, provincial, and municipal governments (Rideout & Reddick, 2005). But is this realistic to expect? Moll (2012) speculates that the policy emphasis on social cohesion, a general thread running through many of the initiatives of Jean Chrétien's government, including CAP and its siblings in the Connecting Canadians family of programs, was a reaction to the neo-liberalism of the 1980s and early 1990s, and that the erosion and final cancellation of CAP under successive Martin and Harper governments represents a swing of the pendulum in the other direction, resulting in a withdrawal of the state from its role of providing for the common good combined with increasing pressure on voluntary organizations to adapt to a managerial model that imitates the practices of for-profit enterprises. As Howard et al. put it (2010, p.123), "digital divides may persist if the state retreats too much from investment in public goods such as telecommunications infrastructure, informational literacy, and cultural content production"-and this caveat describes the very situation that we currently are in. The unhappy conclusion seems to be that, in Canada, only the two senior levels of government have the revenue base necessary to provide funding consistently across the country, yet neither seem disposed to do so.

One possible response to this quandary may be to reframe the problem. When the Community Access Program was restricted in its scope to providing connectivity, as important as that objective is, the program became the prisoner of diminishing returns. As the majority of Canadians become connected participants in the networked society, it becomes increasingly harder to reach the remaining ones who are left out. However the 10% who rely on public access sites to connect to the Internet are only part of a much larger population with unaddressed needs. In the case of literacy, there is a small core group of people who cannot read at all (the pure illiterate), but also a much larger group of people who are unable to perform basic tasks associated with daily living or employment because of inadequate reading skills (the functionally illiterate). A similar situation exists with ICT use, where many people have access to ICTs, but cannot use them effectively (sensu Gurstein, 2003).13 By extending the scope of the government's ICT policy from a narrow focus on access (and on those who are excluded from access by absolute poverty) to include any Canadians and Canadian communities that are not currently using the available ICTs to their full potential, the program or programs that would succeed CAP would have a much higher visibility and a potentially broader base of political support.

What constitutes effective use of the Internet, or other ICTs, is very context-specific; it is tied to the citizen's individual needs and circumstances, and to the characteristics and processes of the community in which the citizen is placed. This is why promoting effective use of the Internet and ICTs in general is a problem ideally suited to a Community Informatics approach. Thus any programs or programs that attempt to take the place of CAP should have an expanded mandate to give community members "the knowledge, skills, and supportive organizational and social structures to make effective use of [ICTs] to enable social and community objectives" (Gurstein, 2003, "Access and beyond", para.19).

THE BROADBAND DIVIDE AND THE FIRST MILE

The exclusion of remote and rural communities from full participation in the economic and social life of the nation because they lack affordable and reliable broadband access to the Internet remains a challenge for any program that aims to fill the void left by the end of CAP. The Government of Canada included as part of its recent economic stimulus package a three-year plan to fund broadband projects in unserved communities (McKeown et al., 2010). This program, Broadband Canada: Connecting Rural Canadians, was not extended past its scheduled 2012 expiry; the federal government appears headed in the direction of relying on commercial operating companies for further build-out of broadband in remote areas, perhaps under the impetus of regulatory incentives or concessions.14

Telecommunications planners often use the term "last mile" to describe the connections that link private homes and businesses to the service provider's network backbone, or, in general terms, the neighbourhood-level infrastructure for a particular ICT ("What is last-mile technology?", 2005). As a paradigm for ICT deployment, the term "last mile" implies a pre-existing, centrally planned and managed network, to which individual premises and communities are connected incrementally, and generally at the convenience of the network operator. At the margins of the network, where costs per subscriber are higher and the operating company experiences diminishing returns on investment, new subscribers are added slowly, if at all.

The original use of the term "first mile" in opposition to "last mile" in this context has been attributed to the African activist and poet, Titus Moetsabi (Paisley & Richardson, 1995). A First Mile approach inverts the relationship between the community and the network by giving primacy to the community's needs and expectations. It advocates development that is initiated by and controlled by the local community, not imposed by external agencies or forces. The community is enabled to formulate its needs and concerns before the planning and implementation of the ICT infrastructure begins. After implementation of a first-mile solution, the community retains ownership, control, and even day-to-day operation of the technology. Because the community owns the technology, it can use it in any way that it needs to, using it for new purposes or mixing it with other technologies, which is often not possible when the access network is controlled by a commercial operator with no obligations to the community (McMahon, O'Donnell, Smith, Walmark, & Beaton, 2011). The First Mile approach to broadband development can be employed for any geographically and socially distinct communities of place, but, as McMahon et al. (2011) point out, is especially well suited to First Nations and Inuit communities.

A First Mile approach to bringing broadband Internet access to isolated and lightly populated regions is a natural complement to a nation-wide objective of promoting effective use of the Internet and ICTs in general. The proximate result of a First Mile implementation, namely, the availability of broadband connectivity throughout the community, provides parity with urban and other well-serviced areas where both fixed and mobile broadband are readily available. The community can then leverage the availability of high-speed Internet to set up a free telecentre, for example, or to acquire low-cost terminal devices, or devise its own ICT training and coaching programs, or adopt whatever other initiatives it finds most appropriate to promote effective use for all members of the community, including those who are disadvantaged or have special needs. (The website www.firstmile.ca showcases a variety of initiatives by First Nations communities across Canada that exemplify this model). Local ownership of network infrastructure does not directly address aspects of the digital divide such as lack of adequate end-user hardware and software, or the need for contextually appropriate ICT skills development, but there is reason to hope that it can serve as a catalyst for other initiatives that do so. The focus on community involvement and community ownership in the First Mile approach greatly increases the likelihood that the new connectivity will be used to deliver community-based and culturally relevant services, will be integrated with education and training for effective ICT use, and will promote social and economic development within the community.

CONCLUSION

As Canada's flagship program for promoting Internet access for all Canadians, the Community Access Program enjoyed a reasonably successful 17-year run, bringing Internet access into remote and sparsely populated areas, as well as making it available to some of Canada's neediest citizens. In particular it has been a boon to public libraries, being one of the contributing factors to what has become the nearly ubiquitous presence of library-based free Internet access.

The winding up of the program over the last five years, culminating with its final cancellation in 2012, has thrown into sharp relief what is perhaps the program's greatest failing: an inability to develop thriving and sustainable institutions dedicated to delivering ICT solutions relevant to the communities in which they were rooted. Like the community networks that preceded them, community telecentres in Canada seem doomed to become a thing of the past, except those embedded in organizations large enough to fund them out of their existing revenue streams (this by and large means the public libraries in urban areas and the branches of large regional public libraries).

Despite government claims to the contrary, a significant and persistent digital divide still remains. Age, education level, and rural location are sometimes factors in the inequality of access, but the single biggest predictor of a person's inability to receive ICT services is poverty. As community organizations and small, stand-alone libraries in remoter regions are forced to stop providing free Internet access, the rural poor will suffer disproportionately and become doubly divided from the on-line public squares and marketplaces of Canada's economic and culture life. Those in larger centres who are able to access the remaining public Internet terminals will still find themselves at a disadvantage compared to members of households where Internet-enabled devices are available to them whenever they want. There is also a hidden divide experienced by those who have network access in the home and devices to use it, but are unable to make effective use of the Internet and other ICTs, either because as individuals they do not have the skills and training necessary to get the full benefit of their ICT use, or because the digital tools and content available to them are not relevant to the contexts and processes of the communities in which they live. Any program that seeks to build on the successes of CAP needs to be able to address these different forms of digital divide; any program that seeks to avoid the failures of CAP must be flexible enough to allow each community to visualize and implement the ICTs best suited to it.

ENDNOTES

1. Unless otherwise attributed, all information in this section is taken from Moll (2012).2. Other programs under this agenda included SchoolNet, VolNet, LibraryNet, and the Smart Communities programs (Clement et al., 2004).

3. Exact numbers are hard to obtain for the latter years of CAP's life, but Moll (2012) estimates that there were about 3,000 sites in 2009.

4. Industry Canada is a department of the Canadian government, established by the Department of Industry Act, whose mandate is "to help make Canadian industry more productive and competitive in the global economy, thus improving the economic and social well-being of Canadians." It specializes in micro-economic policy and is primarily concerned with establishing conditions necessary for the success of Canadian enterprises (Industry Canada, 2012).

5. Mayes' words are reminiscent of the infamous quip by former U.S. FCC Chairman Michael Powell: "You know, I think there's a Mercedes divide. I'd like to have one; I can't afford one" (Shade, 2002).

6. In the early days of the Internet, many white-collar workers had access to the Internet at work but not at home. This situation is probably uncommon today except in remote areas where residential broadband is unavailable and thus the workplace is the only place with full-speed access. In urban areas, home access is probably a good proxy for access in general.

7. Question HA_Q02 "What are the reasons your household does not have access to the Internet at home?" Respondents could select more than one answer from the list or supply their own; thus the percentages in this category do not add to 100%.

8. These figures include any type of Internet access, including dial-up; they do not take into account differences in speed and reliability of service.

9. Ultimately, the Guelph library was able to make up its $6,800 finding shortfall through fund-raising: late in 2012, a city councillor launched a social media campaign that collected enough donations to pay the full cost of providing public Internet access through 2013. However the library board remains without a plan to fund its public access terminals in 2014 and beyond (May, 2012).

10. The Government of Canada estimated that CAP funds make up just 20% of the cost of running a typical site with the other 80% leveraged within the community itself (Moll 2007a). But this statistic raises the question why CAP sites typically close when they lose their CAP grants. There seems to be a lack of research on this topic, but it is probable that in some cases the site has outlived its usefulness, and the removal of the grant provides the impetus for the grant recipient to reallocate the remaining 80% of the funding to align better with the organization's core mission. Alternatively, I suspect that some of the support counted towards the leveraged 80% takes the form of grants-in-kind, while the CAP funds provided the recipient agency with an irreplaceable source of cash needed to pay for expenses such as ISP fees.

11. Another related possibility, an an alternative to the pay-for-service model, would be to obtain revenue through advertisements that would display on the public access terminal periodically throughout a user session. I have not seen any mention in the literature of community access sites that have attempted this, most likely because a typical community access site simply doesn't have an audience big enough, compared with other advertising media, not to mention that people who cannot afford their own Internet connection are probably not a particular attractive target for advertisers.

12. It is worth pointing out that the kind of access provided by public access terminals is a necessary but not sufficient condition for full participation in contemporary Canadian life. A person who uses a public Internet terminal a few hours a week can accomplish many things, but will not have the same opportunity to learn about and master ICTs as someone who has them always at the fingertips. "There is a divide between families that can afford Internet access and can access it in their own home (and can develop the technical skills necessary to productively use the Internet) and those who cannot." (Howard et al, 2010). Hyperconnectivity - the trend for households to have an ecosystem of interconnected and Internet-aware devices such as media players, game consoles, or smart appliances - is likely to even further widen the gap between haves and have-nots.

13. One concise definition of effective use is that it is "the capacity and opportunity to successfully integrate ICTs into the accomplishment of self or collaboratively identified goals" (Gurstein, 2003, "Effective use," para. 2).

14. The only initiative for extending rural broadband in the 2012 budget was a promise to attach conditions to the upcoming auction of 700 MHz wireless spectrum. According to the government's budget plan, these conditions would require auction winners that end up with control of two or more blocks of 700 MHz spectrum to "deploy new advanced services to 90 per cent of the population in their coverage area within five years and to 97 per cent within seven years" (Finance Canada, 2012, p. 177).