ICT for Sustainable Development: An Example from Cambodia

Research Scholar, Centre for Strategic Economic Studies, Victoria University, Melbourne, Australia. Email: helena.grunfeld@live.vu.edu.au

INTRODUCTION

This article suggests that a framework integrating the capability approach (CA) and the information and communication technologies for development (ICT4D) discourse on sustainability/climate change would be a useful tool for the design and evaluation of ICT4D initiatives, expanding the consideration of sustainability of the former and the social dimension of the latter.

In an effort to hasten the deployment of ICTs in the developing world, shared access facilities, with an emphasis on Internet access, became a common mechanism for extending access to previously underserved areas from the 1990s. Pilot telecentres often lacked funds to continue and scale, despite their inclusion in the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS, 2003a) Plan of Action: 'to connect villages with ICTs and establish community access points' (Point B.6.a) and in universal access policies in 29 countries in 2009 (ITU, 2011a). Such access points can range from commercial Internet cafes to multi-service social gathering places, which in addition to offering ICT services are learning and business centres. Some centres defined specific social objectives, whereas others provided Internet access in the spirit of "build it and they will come." While some evaluations of such centres have been informed by specific development-oriented conceptual frameworks, others have been atheoretical, from a development discourse perspective.

Except for occasional references to the potential of such initiatives (UNCTAD, 2007; UNESCAP, 2008) and sporadic announcements of new telecentres, their unsuccessful quest for long-term viability might have tempered the previous enthusiasm. With the extension of mobile services to previously unserved rural areas, the view, spurred on by arguments that mobiles are more affordable and accessible (Rashid & Elder, 2009), is now emerging that such centres may no longer be needed (Howard, 2008; Souter et al., 2010). Limited convincing evidence showing what difference telecentres have made, might have reinforced this view. Accordingly, mobiles have assumed a predominant place for most ICT4D initiatives and research. Souter, et al. (2010) ascribed, at least partially, the success of mobiles to their greater scale of impact:

'In the development arena, many programs to support Internet access (for example through tele-centres)...... have not had the scale of impact that had been anticipated. Instead, over the past decade the market-led development of the mobile communications sector has generally had a stronger impact on society and on individual lives in low-income countries than the growth of the Internet' (p.34).

Quantitatively, mobiles clearly dominate the ICT landscape in the developing world, but there is no dichotomy between these and Internet, with the two technologies merging. Internet is often accessed via mobile networks in developing countries, as 3G and 4G extend to rural areas and the networks designed for mobile handheld devices are sometimes used for fixed wireless access in the absence of cost-efficient First Mile alternatives (see: McMahon, et al., 2010). Rather than a matter of technology, this is an issue of market-led vs. interventionist approaches, with mobiles generally representing the former and telecentres the latter. The focus should be on designing ICT systems to realise their potential for development, regardless of business model or technology. The first step in this process is to define "development" and the CA is a good starting point because of its normative nature and versatility in different domains, including choice and preference revelation, conflict resolution and impact evaluation.

Starting with a brief introduction of the CA, its application and relevance to ICT4D, the next section concludes with exploring the relationship between the CA and the theme of sustainability. Next is a summary of another stream of relevance to this study - the emerging discourse on the role of ICT4D in meeting climate change and other environmental challenges. These two fields of study provide the background to the case study, which introduces iREACH, the empirical research site, and summarises the conceptual framework and methodologies underpinning the enquiry. The results presented in this paper focus on those aspects of the research results that are relevant for sustainability. In addition to identifying benefits in several other domains (e.g. empowerment, education and health), the study found areas in which iREACH had fallen short of expectations. In concluding, the paper suggests that a combination of the CA and the ICT4D/climate change discourses would be useful for considering a potential new role for telecentres in the mix of ICTs used for climate change adaptation and mitigation.

THE CAPABILITY APPROACH, ICT4D AND SUSTAINABILITY

The Capability Approach (CA)

Recognising that several things matter simultaneously, the CA is normative and multidimensional, combining a focus on outcomes and processes, based on principles of equity, efficiency, empowerment and participation. The attention in the CA is on capabilities, which emphasise what people are free and able to do (i.e. the expansion of people's freedom to lead lives they value and have reason to value (Alkire & Deneulin, 2010; Anand, et al., 2009; Sen, 2001; UNDP, 2010). Capabilities, agency and empowerment are as important as what people actually do and achieve with these. Gender empowerment features strongly in the CA literature. Economic freedoms, defined as opportunities to use resources in the context of distributional arrangements of wealth, is only one of five freedoms and opportunities identified by Sen (2001), as characterising human freedom. The others are political freedom, social opportunities, transparency guarantees, and protective security. All freedoms are constitutive of development (i.e. they are relevant whether or not they contribute to the economy).

In contrast to the centrality of income and/or consumption in utilitarian frameworks, the central question in the CA is 'what they are actually able to do or to be' (Nussbaum, 2000, p.12). Offering a normative framework based on human development, the CA has been embraced by the United Nation Development Programme (UNDP), as reflected in its annual Human Development Reports (HDRs), associated human development indicators and more recently, the multidimensional poverty index (UNDP, 2010). The CA has also influenced development thinking more widely, to incorporate human well-being and directing policy efforts towards heath, education and sustainability (Saito, 2003).

The Capability Approach and ICT4D

From a CA perspective, access to ICT is not an end in itself, but rather the means through which valued capabilities can be achieved. Recognising the importance of ICT, Sen (2005) wrote '… access to the web and the freedom of general communication has become a very important capability that is of interest and relevance to all Indians' (p.160) and characterised mobiles as 'freedom-enhancing' (Sen, 2010a, p.2). This association between ICT and freedoms might, at least partially, explain the increasing popularity of applying or referring to the CA in ICT4D research (e.g. Issue 2, 2011, of the journal Ethics and Information Technology was a thematic issue on ICT and the CA). But this literature has not engaged with the sustainability and/or climate change debate and the CA does not seem to have featured in the many recent activities surrounding ICT4D and climate change, possibly due do the ambivalent relationship between the CA and sustainability debate.

The Capability Approach and Sustainability

Considering environmental challenges as 'part of a more general problem related to resource allocation involving "public goods," Sen ( 2001, p.269) has approached these from several perspectives, including the potential environmental damage flowing from unconstrained use of private property. More recently, in the introduction to the 2010 HDR, Sen (2010b), emphasised 'the conservation of the environment and the sustainability of our well-being and substantive freedoms' (p.vi), as profound challenges, expressing confidence that the human development approach is sufficiently flexible to address these issues. A key difference between the general sustainability debate and the way the CA tends to approach this challenge can be summed up as "ethical universalism" (Anand & Sen, 2000). This concept acknowledges equal claims to the capability of leading worthwhile lives in the present and future generations. The focus on capabilities reflects that, as preferences of future generations are unknown, sustainability should be about 'conserving a capacity to produce well-being' (p. 2035), rather than specific resources.

Despite Sen's concerns about the sustainability movement's emphasis on inter-generational, at the expense of intra-generational equality, he acknowledged the broader view taken in the Brundtland report (WCED, 1987):

'It cannot be doubted that the concept of sustainable development, pioneered by Brundtland, has served as an illuminating and powerful starting point for simultaneously considering the future and the present'(Sen, 2002 - web document, no pagination).

But sustainability has not been a central concern of the CA, while the sustainability literature has paid insufficient attention to guaranteed protective security:

'It is worth noting here that even the highly illuminating literature on "sustainable development" often misses out the fact that what people need for their security is not only the sustainability of overall development, but also the need for guaranteed social protection when people's predicaments diverge and some groups are thrown brutally to the wall while other groups experience little adversity'(Sen, 2000, p.37).

This could occur where customary and other rights might conflict - e.g. where indigenous populations are prevented from using natural resources for traditional livelihoods, thereby compromising their economic freedom and social protection, in favour of the freedom of others to enjoy a pristine environment. Conflicting freedoms also arise between the "right" of some to pollute and of others to live in a pollution-free environment (Nussbaum, 2003). The CA has been useful in addressing contestations between incompatible interests through its emphasis on public deliberation, informed by different valuations of nature, rather than market choices (Scholtes, 2010). This has been illustrated for water disputes, another case of incompatible freedoms, featured in the CA literature (Anand, 2007; Khagram, Clark & Raad, 2003).

As the sustainability movement is increasingly integrating ecological, social, economic and cultural dimensions (Bichler, Bradley & Hofkichner, 2010; OECD, 2012), so there are signs of an increasing interest in sustainability issues in the CA discourse (e.g., Issue 1, 2013 of the Journal of Human Development and Capabilities addressed the capability approach and sustainability). The confluence of sustainability and the CA was also reflected in the central theme of the 2011 HDR (UNDP, 2011), which defined sustainable human development as 'the expansion of the substantive freedoms of people today while making reasonable efforts to avoid seriously compromising those of future generations' (p.2). Focussing on the challenges of integrating equity into policies dealing with environmental issues, the report emphasised that the relationship between sustainability and equity is not necessarily positive or mutually re-enforcing. While mediating between such relationships remains a foundational problem of the CA, at the practical level it may be possible to identify policies and practices that do not require compromises between equity today and in the future. The case study in this article, agro-ecological techniques introduced at an ICT4D initiative in Cambodia, is one example.

Although there has been some reference to the CA in the context of ICT4D (e.g. Ospina & Heeks, 2010), more attention to climate change issues in ICT4D/CA research and to human development in ICT4D/environment research could enhance the ability of both fields of study to contribute to the challenge of addressing sustainable development.

ICT4D AND THE ENVIRONMENT DISCOURSE

The burgeoning body of work revolving around ICT and environmental issues recognises the potential of ICT to contribute both positively and negatively to environmental challenges. Some aspects of its positive potential was enshrined in the WSIS Geneva Plan of Action, which encouraged the use of ICTs for environmental protection, sustainable production and disaster forecasting and monitoring systems (WSIS, 2003a). Referring to the Millennium Development Goal number 7, "ensure environmental sustainability", UNICT (2003) pointed to similar contributions, as well as facilitating environmental activism and enabling more efficient resource use. In terms of negative aspects, the lifecycle of ICT devices, from the carbon footprint of their production to energy consumption during use and e-waste at end of life, has received considerable attention, including concerns over the "upgrade treadmill" (Fairweather, 2011).

According to Souter, et al. (2010, p.4):

'Two issues of profound importance lie at the heart of current thinking about the development of global economies and societies: the challenge of environmental sustainability, and the potential of information and communications technology'

Absent from this statement, and from many initiatives in the extensive list of activities and publications in the ICT4D/environment field, are references to domains of human development. The list of initiatives includes a session on "ICT and the environment in developing countries: opportunities and developments" at an OECD, infoDev and World Bank workshop in 2009, which explored the role of ICT in climate change adaptation and mitigation (Houghton, 2009). The 2009-10 World Economic Forum's Global Information Technology Report was subtitled ICT for sustainability (WEF, 2010). In 2010, the Canadian International Development Research Centre (IDRC) invited proposals for commissioned thematic papers on ICTs, climate change and development (Ospina & Heeks, 2010b). The 2011 WSIS Forum released the report Using information and communication technologies (ICTs) to tackle climate change (ITU, 2011b) during e-environment dayi , announced during the Forum. At its sixth symposium on ICTs, the environment and climate change in July 2011, the International Telecommunication Union declared September 5-9, 2011 ITU Green Standards Weekii . Also in 2011, the International Institute for Communication and Development (IICD) arranged a conference on ICT for a greener economy in developing countries. An international conference on ICT for sustainability was arranged in Zurich in 2013 by ETH Zurich, University of Zurich and Empa, Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (Hilty, et al., 2013).

The journal Information, Communication & Society devoted Issue 1, 2010 to sustainable development and ICTs. In one of the papers, Hilty & Ruddy (2010) pointed to ICTs as potential enablers of dematerialised (i.e. using less physical resources, thereby reducing environmental impactsiii ) production and consumption, which they considered a necessary condition for sustainable development.

According to Plepys (2002), the environmental impacts of ICTs can be positive, negative or neutral, and considerably larger, through rebound effects, than direct impacts of ICT production and consumption:

'…it is necessary to look at both ecological and social dimensions. The positive ecological dimension rests on ICTs potential to deliver greener products, optimise the ways of their delivery, and increase consumption efficiency through dematerialisation, e-substitution, green marketing, ecological product life optimisation, etc. The environmental potential offered by the ecological dimension will be fully utilised only under an optimised social dimension, which deals with the behavioural issues of consumption' (p.518).

The importance of sensitising the development discourse to dematerialisation was suggested by Sheehan (2008) in terms of:

'a central challenge for development theory and practice now is to understand and implement rapid growth based on services, and on a closer link between services and the rural sector. Little is understood about how to stimulate service growth in a developing country …..' (p.17).

The initiatives listed above did not sufficiently address possible tensions between environmental challenges and the social dimension. Such matters were addressed by UNDP (2011), which called for the link between economic growth and greenhouse gas emissions to be severed in order for human development to become sustainable. Such broader approach to sustainability provided the conceptual framework for the field research presented in this paper. Another benefit of approaching evaluations of telecentres and other ICT4D initiatives from a CA perspective lies in the multidimensional nature of both the CA and ICT.

RESEARCH SITE AND METHODS

Informatics for Rural Empowerment and Community Health (iREACH) in Cambodia

Established in 2006 and funded by IDRC, iREACH fits under a First Mile umbrella. This community informatics initiative (Dara, Dimanche & Ó Siochrú, 2008) operates at two geographically separate rural areas in Cambodia, Kep and Kamchai Mear (KCM), both located a few hours drive from, but in different directions in relation to, the capital Phnom Penh. Managed by community facilitators (CFs) and equipped with one or several computers, hubs are situated in publicly accessible buildings. Most services are provided free of charge and the CFs assist users facing barriers to effective use of iREACH, e.g. through low literacy levels, thereby reducing the risk that the most disadvantaged individuals might be excluded.

In addition to providing Internet access, iREACH offers training in ICT and topics such as agriculture, health, English as well as skills required to manage the project. Various media are used, with much content developed locally: lectures and discussions within and between the hubs, "mobile" video shows screened in villages and narrowcasts via computer speakers and outdoor loudspeakers. The latter represent an inferior substitute for community radio, which, while forming part of the initial iREACH plans, could not be implemented in the absence of a licence.

Chea Sim University of Kamchaymear (CSUK), a rural agricultural university, has supervised the KCM site since iREACH's inception and has since 2011 been responsible for both sites, but the general direction for content development and other activities is provided by local elected management committee members.

Conceptual Framework and Research Methods

The research was aimed at understanding what difference iREACH had made to the lives of the population within its catchment areas. The research instrument designed for this study was informed by the CA and explored whether and how iREACH had contributed to capabilities, empowerment and sustainability. The conceptual framework informing the study incorporates a longitudinal perspective, pays attention to the micro-, meso- and macro-levels and requires at least part of an assessment to incorporate a participatory methodology.

This paper covers results from the first two research waves, conducted in 2009 and 2010. Data for both years were collected from semi-structured focus group sessions. In addition, data for 2010 include survey results from face-to-face interviews with 120 randomly selected respondents at each site, representing equal proportions iREACH users and non-users, men and women. The survey was conducted for triangulation purposes.

There were 22 focus groups in 2009 and 19 in 2010, with participants in each group invited from a specific sub-segment, such as teachers, NGO employees and volunteers, youth, farmers, women, micro-business owners, village leaders and commune council members. This structure was designed to facilitate discussions, expecting participants to be more at ease with people from similar backgrounds (Burkey, 1993). There were between four and nine participants per group and in addition to one specific women's group at each site each year, women participated in most of the other groups, making up 42% and 50% of total participants in 2009 and 2010, respectively. Participants were drawn from across age groups above the age of 18. Despite the intention that participants be the same in both years, this was achieved for only half, due the rest being unavailable.

The sessions started with discussions on participants' views about their communities, recent improvements, iREACH's role in those and future aspirations. The next topic was about iREACH and its contributions, with questions including most significant changes and main benefits derived from its activities and services. There were also specific questions dealing with the influence of this project on equality, gender empowerment, family relationships and local culture. Male iREACH staff facilitated the sessions and interpreted between Khmer and English, but this did not seem to inhibit the female participants, many of whom were articulate and outspoken, whether praising or criticising aspects of the project. The risks inherent in the active involvement by staff in evaluations can be balanced by its benefits (e.g. DFID, 2009; Guba & Lincoln, 1981), such as capacity building and exchange of information between staff and participants. Further details on the research methodology, including a discussion on rigour and bias and wider research findings can be found in Grunfeld, Hak & Pin (2011). Presented in the context of some other research results, the rest of this paper focuses on findings related to sustainability.

RESEARCH RESULTS RELATING TO SUSTAINABILITY

As most respondents had not seen a computer prior to the launch of iREACH, there was much excitement about acquiring digital skills, particularly for children. However, it was not the access to ICT as a technology that inspired participants, but rather the infusion of external information, breaking what they perceived as insularity stemming from lack of information from "the outside world." Appreciating the intrinsic and instrumental value of information, there was a distinct awareness of how it can contribute to sustainability in the natural, social, and economic spheres. The interrelatedness and dynamics between capabilities in the different dimensions made it difficult to disentangle sustainability from other findings. For example, capabilities of being knowledgeable and healthy contributed to sustainability, as did empowerment, agency and positive social capital - other benefits afforded through iREACH, but not only through ICT as a technology. Empowerment and agency were important drivers in propelling innovative activities, some of which challenged villagers to enter new arenas in search of livelihood opportunities, including experimentation with new farming methods. Information, learning and knowledge were common themes across several dimensions.

Participants perceived that iREACH had made a reasonable contribution to sustainability, by enabling villagers to use its facilities in diverse ways to improve their livelihoods. The many pathways to sustainability occurring simultaneously at individual or community levels did not translate to self-sufficiency. Among the sustainability categories were: agriculture, livelihood diversification through entrepreneurial activity and employment. While new digital literacy skills could lead to diversification into non-farm activities in the longer term, only the occasional micro-businesses had used iREACH's facilities and it had not attracted any new ICT-based businesses (e.g. for outsourcing). Surprisingly, hardly any respondents reported using iREACH for employment-related activities, whether searching for vacancies or writing CVs. Its most significant influence was on farming, an activity for which iREACH also seemed to have greatest prospects of contributing to sustainability and climate change adaptation and mitigation capabilities. With agriculture being the main occupation of 97% of households at both sites (NCDD, 2009) this is also the most important livelihood source. The focus of the remainder of this paper is on findings related to farming.

When considering the role of information for improved efficiencies, it is useful to differentiate between information pertaining to allocative vs. technical efficiencies (Blattman, Jensen & Roman, 2003). The latter covers information about practices designed to improve yields, and the former other means of generating higher incomes, such as more efficient marketing, e.g. through price information. While the farm produce market price information disseminated by iREACH was raised in approximately one third of the groups in different contexts throughout the sessions, only the occasional participants claimed to have applied this information when negotiating prices for their produce. Among them was one participant in the 2010 women's group, who had been successful in obtaining a higher price. A complex set of constraints limit the capacity of farmers to act on such information, particularly the poorest farmers, who are often indebted to traders and lack the freedom to decide whether to sell their produce at a certain price. Those not indebted in this way might lack resources for transport and/or storage, reflecting the social reality of differentiated access to resources. There was thus a perception that pricing information disseminated by iREACH did not increase the real choices of most farmers, a finding also made in other contexts (e.g. Heeks & Kanashiro, 2009; Sreekumar & Rivera-Sánchez, 2008), while other researchers have found evidence consistent with more widespread benefits.

Whereas local power relations limited the scope for realising the potential of market price information, there was greater scope for farmers to benefit from technical efficiencies stemming from the application of new practices, as discussed in the next section.

RESULTS RELATING TO TECHNICAL EFFICIENCIES OF FARMING

The introductory parts of the sessions reflected the utmost importance of agriculture in the study areas, with three quarters of groups in 2009 and slightly more than half in 2010 mentioning farming when discussing major strengths of their communities. A high proportion of participants also cited agriculture when contemplating recent improvements, pointing to water infrastructure, such as dams and irrigation that reduced the dependence on rainfed farming. Although iREACH could not take credit for this, villagers attributed several other enhancements to this project, including the many ways in which it had provided guidance on agriculture techniques (e.g. dissemination of information on new crops, organic farming, and pest- and disease control). The discussions were very much about how villagers went about acquiring, sharing, and making use of this information.

As well as initiating dissemination through its various channels, iREACH assisted villagers who came to enquire about specific information. Such interactions would then include other hub visitors. Through iREACH, several participants reasoned, there were new ways in which villagers could obtain and exchange information for yield improvements, crop diversification and reduced farm input costs. Participants spoke of how iREACH had encouraged villagers of both genders to experiment with new crops and farming processes and identified pathways from these, via qualitative and quantitative yield improvements, to better livelihoods.

Other organisations also provided agriculture training in villages within iREACH's catchment areas, including the International Fund for Agriculture Development (IFAD), the Cambodian Center for Study and Development in Agriculture and Bridges across Boarders (BAB). In addition to acquiring information from iREACH first, participants explained how the hubs strengthened training provided by other organisations, supplementing what they learnt from those. Such on-demand information was sometimes the last step in the knowledge-to-practice chain, serving as reinforcement - a driver for effective innovation diffusion (Rogers, 2003).

Access to on-demand information at iREACH distinguished it from other agricultural training providers and it was claimed in several groups that this had facilitated the application of new farming approaches, where villagers first learned about these from other agencies. For example, a woman in KCM first learned from IFAD how to grow watermelons in the rice fields after the rice harvest and then claimed she supplemented that knowledge with information from iREACH. Some in the Kep youth group recollected how they, after learning from BAB about harmful impacts of chemical inputs and alternative methods, acquired further guidance from iREACH, before disseminating information in their villages. This supplementary function (using centres for verifying and/or complementing information from other sources), raised confidence in applying new practices and disseminating innovations.

While there were no striking differences in the results between the two years, discussions in 2010 yielded more concrete examples, particularly in KCM, compared with 2009, when participants rarely cited specific cases of improvements. The greater emphasis on agriculture in KCM could reflect the presence of CSUK, the agricultural university and the involvement by its staff in iREACH. Participants talked about novel farming techniques they had employed and crops they had experimented with, assisted by information acquired via iREACH. Some gave examples of increased yields through better understanding of soil properties and seed selection. Of particular interest for this article is that approaches within the broad category of agro-ecology received more attention in 2010, with participants in several groups claiming they had adopted organic farming methods. They associated several positive features with these - taste, texture, yields and reductions in costs and pollution (the latter resulting from composting instead of burning leaves and crop residue). These practices were also used in home gardens, which have been identified as a good strategy for overcoming micronutrient deficiencies (Muller & Krawinkel, 2005). According to one participant, there were 50 home gardens in her village, compared with 10 when iREACH started its operations.

RESULTS RELATED TO FARMING FROM SURVEYS

The surveys confirmed views about iREACH's influence on agriculture, with approximately 36% of interviewees including something on this theme in many open-ended questions across a range of topics. Only a few referred to market price information. The average proportion masks significant differences between the sites; in KCM, at least 63% listed something associated with agriculture, compared to only 10% in Kep. There were also qualitative variations between the sites. In Kep, respondents mainly used general terms, whereas they were more specific in KCM, mentioning natural fertilisers, higher rice yields and planting new vegetable types. Only 50% of those in KCM who included agriculture in response to questions about most significant change and main benefits, identified themselves as iREACH users, pointing to possible spillover effects.

IMPLICATIONS AND DISCUSSION

After decades of neglect, there has been renewed interest in agriculture (World Bank, 2007a), both in response to food price rises and in recognition of growth in this sector having greater potential to contribute to poverty reduction than growth in most other sectors, particularly in poor, agriculture-based economies (Loayza & Raddatz, 2010; Ravallion & Chen, 2007). IFAD's (2010) rural poverty report suggested it is labour-intensive small-hold farming, rather than capital-intensive commercial agriculture that holds promise for poverty reduction, and accordingly included recommendations in support of small-holders and recognised ICT as an important driver for rural economies. The importance of ICT for agriculture has long been recognised by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), an early adopter of ICT for development. The strong emphasis in the IFAD report on strengthening individual and collective capabilities of rural people indicates some influence from the CA.

Sustainability, Capabilities and Poverty Reduction - How They Relate

While the field research does not allow claims to be made about iREACH's contribution to poverty alleviation, at face value, farmers were assisted by advice on crop management in ways that might have contributed to poverty reduction. The small steps in the direction of sustainability and greater resilience, resulting from more knowledge and better skills, are potential opportunities for climate change adaptation and mitigation capabilities. A confluence of several interdependent processes and benefits supporting this assumption was noted. Firstly, the expansion of capabilities and choice (i.e. new opportunities and the freedom to experiment, using information that iREACH made more accessible). The learning trajectory, facilitated by interaction with others, paved the way for equitable ways of achieving sustainable livelihoods. Secondly, the adoption of agro-ecological techniques involved productive use, instead of burning, of organic matter for composting, thereby reducing pollution - one of the benefits of organic farming for sustainability and climate change mitigation (Kilcher, 2007; Niggli, Earley & Ogorzalek, 2007).

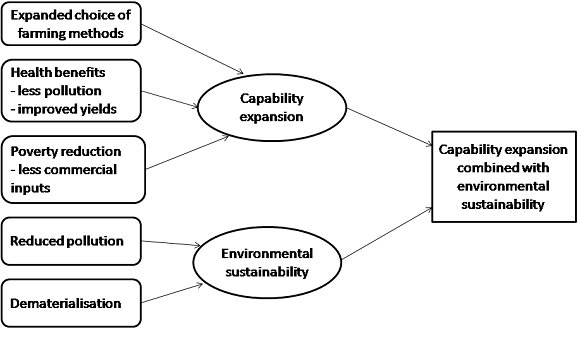

Thirdly were benefits related to the capability of being healthy and (perceived) positive health outcomes from improved air quality with less burn-off, which also entailed less waste of resources. As inorganic fertilisers emit methane gas and contaminate land and water (IAASTD, 2009; UNDESA, 2011), less use of chemical inputs meant lower risks of water and aquatic food pollution affecting organisms not intentionally targeted. Cambodia suffers from specific health issues arising from inappropriate pesticide use, because farmers often ignore or misunderstand Vietnamese and Thai labels on illegally imported sprays (Jensen et al., 2011). Another potential health advantage, although not explicitly mentioned, could stem from improved food security and nutrition. A study by Branca, et al. (2011) noted that agriculture methods most promising for food security by smallholders are also effective for mitigating climate change in humid areas. Crop diversification, also encouraged by iREACH, has been suggested as one pathway out of poverty (Krishna, 2006). The fourth benefit relates to poverty reduction. Less reliance on external inputs that are subject to price shocks could have positive distributional impacts, as organic techniques would lower the production costs in terms of monetary, but not necessarily labour inputs, thereby benefitting also the poorer farmers and link environmental benefits of agriculture to equality, a perspective consistent with the CA. Figure 1 summarises the above discussion.

It is important to note that not everyone in the iREACH coverage area could benefit, particularly not the poorest villagers, who are often landless (3% in Kep and 6% in KCM (NCDD, 2009)), but they could enjoy the positive externalities, such as reduced pollution, arising from the new agricultural technology options.

Using less potentially harmful agrochemical inputs, the new techniques contributed to dematerialisation, a key element of sustainability, as did the reduced energy consumption stemming from substitution of imported produce with home grown vegetables. Except for iREACH being a "service", there were only limited signs of dematerialisation related to service based growth in the rural sector; the challenge posed by Sheehan (2008) to development theory and practice.

With respect to the ecological footprint of iREACH's infrastructure and activities, this research did not attempt to measure whether the environmental gains were sufficient to offset the carbon footprint of the hubs and the additional fuel required by those travelling there by motorised vehicles. Most of the users walked or used bicycles.

It Is About Knowledge

Designed as a study of the contribution of ICT, what emerged was much wider. While a valuable ingredient for facilitating exchange of information through its ability to take advantage of knowledge developed in other places, it was not ICT in itself that paved the way for this focus on organic farming, but also knowledge and activities undertaken by those involved, facilitated by convenient access to ICT. This centrality of knowledge was embodied in Article 1 of the WSIS (2003b) Declaration of Principles: '…where everyone can create, access, utilize and share information and knowledge, enabling individuals, communities and peoples to achieve their full potential in promoting their sustainable development and improving their quality of life'.

Central to both capability expansion and agro-ecology (de Schutter, 2010), knowledge, in this case intermediated, managed to shift much of the decision-making prerogative into the hands of farmers, as they could apply the knowledge without additional financial resources. Through its venues where farmers could meet, iREACH encouraged intermediation between modern science and participatory forms of local knowledge co-production. Those who did not frequent the hubs could participate in this process indirectly by observing those who experimented and subsequently adopt the methods they perceived as beneficial. Recognising the importance of access to ICTs for information sharing in agriculture, FAO (2011) noted that locations where ICT can be accessed must be suitable, particularly for women. Information on agro-ecology is especially important for them, as this type of farming can, according to de Schutter (2010), benefit women most because of the difficulties they often encounter in accessing external farm inputs.

Also notable about the findings on organic farming is that this activity did not form part of the original project objectives or design, but resulted from the pragmatic pursuit of what was relevant for villagers in the form of an "opportunity-driven" innovation system (World Bank, 2007b) with emergent properties. According to Pant & Heeks (2011), developments arising in an unplanned manner can form important elements of climate change adaptive systems and they suggested a new role for telecentres, combined with mobiles, in enlisting ICTs to deal with climate change. They emphasised that this would have to be accompanied by deliberate development of capacities. The future of telecentres, as a First Mile option, may well hinge on carving out a new niche as part of a sustainable development equation, which would benefit from a greater variety of knowledge sources and information dissemination channels. Aware of local information needs, where to obtain relevant information and easy access to it, telecentre staff can act as knowledge brokers for sustainable agriculture practices, as some already do - e.g. in the village knowledge centres operated by the Indian MS Swaminathan Research Foundation, which also uses the centres for disaster risk management (UNESCAP, 2009). However, too much reliance on intermediation, might also create dependency, which could inhibit empowerment and capability expansion.

Policy Implications

The challenge is how to harness benefits arising from emergent adaptive systems at the local level to a magnitude where they might realise economies of scale and scope. In addressing this challenge, an understanding of the linkages between the micro-, meso- and macro- levels is important, as a patchwork of individual local emergent adaptive systems is unlikely to scale efficiently. At the macro-level, the capacity to grasp such opportunities might be limited. The meso-level is better equipped to take into account local needs and priorities and may also be better able to foster ecological land use. Both of these levels can play a role in mediating information and have more resources to act in a manner that can reduce risks and vulnerabilities (Duncombe, 2006). Where the meso- and macro-levels do not engage in appropriate policies to encourage and facilitate agro-ecological practices in a timely manner, local communities can, as they already do, pioneer these, thereby building a knowledge base that can be exploited by governments when they are ready to move on this issue.

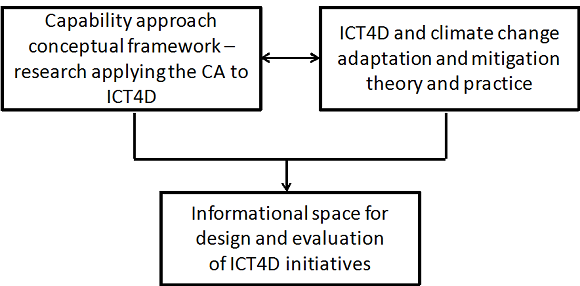

As suggested by Madon, Sahay & Sudan (2007), a CA perspective provides an avenue through which insights into the interaction between the different levels can be improved. This, in combination with the importance of individual and collective capabilities for sustainable agricultural intensification (IFAD, 2010) and the CA's multidimensional focus, suggest this approach as a possible framework for bringing attention to the potential role of telecentres, in combination with other forms of ICTs, to contribute to sustainability. With its normative grounding, the capability perspective would also guard against concentrating solely on ecological sustainability, at the expense of human development factors. The interaction between the CA and an environmental perspective could form the basis of an informational space for design and evaluation of ICT4D initiatives, as shown in Figure 2.

With more studies exploring such common ground between the CA/ICT4D and the ICT/environment discourses, it might be possible to produce a critical mass of empirical evidence pointing to the potential of telecentres to become one of several ICT tools for climate change adaptation and mitigation, supplementing their roles as First Mile options.

LIMITATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

The analysis points to iREACH having played a role in introducing and enhancing the use and expansion of sustainable community-led development through the use of agro-ecological techniques. Through information dissemination using a range of channels and facilitating information exchange between farmers and community facilitators, it demonstrated that public access through community-driven telecentres expanded capabilities in a way that complemented market-driven approaches to ICT.

However, as a non-representative study of one project over a limited time period, the findings cannot be generalised. It is possible that different findings would have emerged from a representative sample, as indicated by the relatively low incidence of references to organic farming in the surveys and the differences between the sites. Furthermore, important parameters were not measured in this qualitative study, including the extent to which organic agriculture techniques had been diffused, quantification of benefits and attribution of these to iREACH vs other organisations. As there are few, if any, empirical studies of telecentres showing a link to positive environmental outcomes, the interest in more sustainable land management practices at iREACH could be a unique occurrence, possibly associated with the agricultural university managing the project. If the latter, this could also be a valuable insight, particularly understanding why Kep did not promote agro-ecological methods to the same extent, or if it did, why it did not register as much with the informants. Despite the above qualifications, a case can nevertheless be made for exploring this issue further.

More in-depth research would be required, both at iREACH and other telecentres, focusing on the contribution these can make to achieving combined environmental and social objectives, in addition to their role as a First Mile option. Such research might look at the way in which they can encourage continuous learning and link small-hold farmers in different locations and with institutions. Subject to the outcomes of more rigorous studies validating the potential described in this paper, such research could inform policy analysis and debates on the role of telecentres for sustainability and shape policies that could enlist them in the service of climate change adaptation and mitigation. It is not expected that there would be a straight line between telecentres and positive climate outcomes, but rather a winding path of experimentation and research, reflecting the diversity and dynamics of agriculture systems, political, economic, social and cultural contexts. These all demand attention and the CA is equipped to play a prominent role in this area, by strengthening the conceptual foundation of empirical research and policy dialogues on ways in which ICT can be used to promote sustainable development that combines social, economic and ecological dimensions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The contributions by iREACH staff, particularly Tara Pin, Sokleap Hak and Dara Seng, focus group participants and survey respondents are greatly appreciated. I am grateful to Professor John Houghton, Victoria University, Australia, for his guidance on the overall research project and comments on an earlier version of this paper and to the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful and valuable comments on a previous version.

ENDNOTES

i

http://groups.itu.int/wsis-forum2011/Agenda/Highlights/EEnvironmentDay.aspx

ii http://www.itu.int/ITU-T/worksem/climatechange/index.html

iii One example could be reading online instead

of printing material.