Frontline Learning Research Special Issue Vol.9

No.2 (2021) 145 - 169

ISSN 2295-3159

1University of Gothenburg,

Sweden

2University of Padova, Italy

Article received 17 May 2020/ revised 30 November / accepted 4 December / available online 11 March 2021

The aim of this study is to shed light on the ways in which transitions and support are framed in policy contexts in relation to widening participation in higher education (HE) in Sweden and Italy. More specifically, this study investigates the ways in which the discourse about the inclusion of migrant students in HE is framed in relation to the kinds of support for this group offered in two higher educational institutions, in Sweden and Italy. Furthermore, the study sheds light on the ways in which policy ideas about transition and widening participation are enmeshed in the students’ narratives and how they affect their experiences of participation, normalization and marginalization in HE. The analysis includes two datasets: i) national policy, laws and regulations and webpages of a selection of national universities and university colleges; and ii) ethnographically generated data that builds upon a case-study design and consists of audio recordings of informal discussions and interviews with students. We are, in this study, interested in framing diversity in terms of a move beyond the naturalization of hegemonic stances where labelled “Others” (e.g. based on cultural/ethnic background, functionality, socio-economic status) are treated as essentialized or mutually exclusive categories. One of the central, frontline contributions of this study, lies in its attempts to analytically scrutinise processes of inclusion and marginalisation that include a broad analytical gaze. This allowed us to analyse the mismatch between the range of support provided, and the actual needs and challenges that migrant students meet in their transition and participation to higher education in two European countries.

Keywords: Transitions; widening participation; migrant students; higher education; vertical case studies.

Due to the migration waves in the past three decades in the geopolitical spaces of Europe, student heterogeneity has gained new dimensions in addition to social and economic mobility. European countries have faced and are facing similar challenges with regard to the inclusion and integration of migrants in all sectors of society, not least in higher education (HE). Mobility is here understood as a human condition wherein contemporary migration is no longer framed as a “unidirectional migrant passage” (Guo, 2015, p.9) but rather as “the multiple and circular migration across transnational spaces” (p. 7). Such a precarious condition, we argue, may afford and/or prevent individuals’ opportunities for full participation and socialization in society in a range of different ways.

Over the past century, higher educational institutions have started to engage with a compelling agenda for the inclusion and integration of an increasingly “diverse” student population. In the geopolitical space of Sweden, issues of openness and inclusion have marked educational policy since World-War II, not least in regard to higher education. A government proposal “The open university” (Prop. 2001/02:15) discusses widening recruitment and participation where fundamental issues include the need for the student population to reflect the makeup of society generally, and a belief that all levels of diversity, including the heterogeneity of ideas, beliefs and approaches, is key for achieving academic excellence. In Italy, higher educational institutions’ policies concerning the inclusion and promotion of diversity, are informed by regulations and resources by the Ministry of Interior and by the Ministry of Research and University. For instance, in 2020, migrants who were granted international protection by the Ministry of Interior were offered 100 study grants to access Italian universities. Furthermore, UNHCR produced a specific Manifesto for the inclusive university that addresses the inclusion and integration of refugee students and academics (UNHCR, 2019), signed by 43 Italian universities so far.

There are, however, several tensions between how the discourse about diversity, integration and widening participation gets framed in policy documents like the ones briefly presented above, and the ways in which practices of inclusion and support play out in the everyday life of students and academics. In the present study, the university is understood as a complex site where political, economic and social interests intersect (Bacevic, 2019; Tummons & Beach, 2019). This involves the idea that the university is playing a major role in the global corporatisation, marketisation and massification of (higher) education on the one hand (Giroux, 2010; Tight, 2019), and the changing and growing societal expectations on HE to support democracy and equity in the 21st century on the other (see also Fox, Baker, Charitonos, Jack, & Moser-Mercer, 2020). Furthermore, the fields of intercultural studies and global education have yet to come to terms with diverging understandings of cultural differences according to reference frameworks that prioritize value rubrics, cultural mobility and “effective” cross-cultural communication in contrast with social mobility and critical decolonial perspectives (Walsh, 2012). The research presented in this study is an attempt to shed light on and unpack some of these tensions and contradictions.

Taking the above as points of departure, we are, in this study, interested in framing diversity in terms of a move beyond the naturalization of hegemonic stances where labelled “Others” (e.g. based on cultural/ethnic background, functionality, socio-economic status) are treated as essentialized and, even worse, mutually exclusive categories. We argue for a conceptualisation of identity, and therefore also diversity, in terms of an intricate process in which the agency of human beings does not exclusively reside in the single individual, but is also always situated, i.e. related to contexts, from specific micro-moments, to macro-structures, of which policies are an important part (see also Ecclestone, Biesta & Hughes, 2010). Diversity, from such a line of thinking, is something that gets done in a practice that is entangled with other practices, both at the micro and macro analytical level. Finding (new) ways to explore and understand practices from such analytical positions is, we argue, of crucial importance when dealing with the study of the many dimensions of life for marginalized groups in society.

In such a line of thinking, practices of being and becoming a student are linked to institutional contexts, social regulations and many other practices in which the social and the material are entangled (Gherardi, 2017). Such a “relational epistemology” (Law, 1994), we argue, highlights the performative dimension of sociomateriality and provides us with the theoretical tools for the study of identity as being in a constant state of becoming, i.e. fluid, ever changing and situated, rather than essentialistic, fixed or static (Hancock, 2016). And yet, “fixed” binary categories (e.g. either you are a migrant or not) are sine qua non conditions and play a crucial role in the ways in which support services, special programmes and educational arrangements are planned and operationalised in policy as well as in practice. Furthermore, diversity is always entrenched in a fabric of ideologies and hegemonies (see e.g. Messina Dahlberg & Bagga-Gupta, 2019). Who is “diverse” is often framed as in need of some sort of institutionalised support in policy (Bagga-Gupta, Messina Dahlberg & Winther, 2016; Bagga-Gupta, Messina Dahlberg & Vigmo, 2020), and this is thought of and done differently in different communities.

The aim of this study is to shed light on the ways in which policy ideas about widening participation, diversity and inclusion in HE are related to practices in the study of students’ institutional pathways in two European countries by answering the following questions:

Given the aim and the research questions outlined above, we use a comparative approach to illustrate the ways in which widening participation, diversity and mobility are both context-sensitive, local phenomena, but also respond to a global discourse of growing societal expectations on HE to include a diverse student population. The analysis is based on two selected European countries, Sweden and Italy, located at the antipodes of the European map. Italy’s geographical position is strategically central for migration waves to Europe that originate from the Global South. Swedish immigration has historically been characterised by labour migration and an integration policy largely based on notions of equality and diversity (in terms of multiculturality and integration, rather than assimilation, see also Kupský, 2017). Thus, the two countries’ ideological and political agendas build upon different cultural and historical frames of reference, that, in turn, affect the ways in which inclusion and integration are framed in policy and implemented in practice. Such perspectives, we argue, deserve further scrutiny from a comparative and multi-scale perspective.

The rather ambitious endeavour to investigate policies and their mutual relations to practice in two different nation-states across time and space has been undertaken in the study of two datasets. These have allowed us to partially connect different levels of analysis from micro to macro levels and to provide further insights on the ways in which students’ lived experiences are mutually entangled with current national and supranational policies about transitions and widening participation in HE.

There is an extensive body of research concerning the intersection of higher education and migration, where the focus lies on migrant students’ lived experience. Students are often framed in the literature in terms of being in a “betwixt space”, a space between home and HE, which risks leading to a sense of not belonging anywhere (Dunwoodie, Kaukko, Wilkinson, Reimer & Webb, 2020; Hope, 2017) or as undergoing a “transitional experience” in the physical context of the university (MacFarlane, 2016). Similarly, the work by Gennep and Maskalaki (Middleton, 2018), focuses on “liminality” as the observation and analysis of factors clustering around the “rites of passage” that mark an individual’s transition from one status to another; and on “emplacement”, i.e. a sense of common identity and place in relation to boundary spaces (such as institutional educational spaces).

Political and policy initiatives that aim to widen participation in HE have been investigated in relation to how potential students experience and navigate ways into academic studies, and what barriers can negatively affect pathways into HE (Farenga, 2018; Lopez Gavira & Moriña, 2015; MacFarlane, 2016). Furthermore, challenges for first-generation as well as low-income students are linked to conditions for guidance and support during the attempt by higher educational institutions to reach these student groups (Brown, Wohn & Ellison, 2016). However, access to information needs contextualization and “translation” from a more knowledgeable person to situate and link that information to students’ everyday practice and social network practices, that, thus, become important access points for the student (2016).

A qualitative interview study in Germany (Schneider, 2018), focuses on Syrian asylum seekers and refugees (ASRs) applying to German higher education. The general entry requirements were linked to constraining financial costs given in the asylum seekers’ and refugees’ accounts of their socioeconomic situation, and were closely connected to an identity marker of being a refugee. Schneider (2018) draws the conclusion that the formal university admission requirements would “morph into practically insurmountable barriers” (p. 468). Other barriers were the language requirements, and the total lack of recognizing previously achieved skills and qualifications, unless academic documents were translated into German for verification.

Further insights provided through research reinforce the necessity to widen the perspective to integrate the multifaceted social practices present in students’ diverse life trajectories (Hope, 2017; Kyndt, Donche, Trigwell & Lindblom-Ylänne, 2017; Trigwell, 2017). Taylor and Harris-Evans (2018) highlight that the “entangled” and “irregular” transition processes must be revisited and reconceptualized to involve students’ lived realities. Similarly, Gale and Parker (2014) point to a lack of research on the “transition as becoming” metaphor, and argue that students’ lives and their realities should become involved. This also means ensuring that other actors, who influence the transition processes, are included to address the complexities found in the non-linear processes of transition across time and space (Kyndt, et al., 2017). Revisiting mainstream norms, and how these impact conditions for transitions processes, calls for more diverse approaches and flexibility concerning the investigation of how students receive support (Taylor & Harris-Evans, 2018), and what it means for “becoming, being and achieving” as a student in HE, as Hope (2017) succinctly puts it. Adopting a linear perspective for how to adapt and conform to being a student in HE, departs from the notion that the student her/himself is involved in the attempt to fit the university student norm (Taylor & Harris-Evans, 2018). To address these challenges, a more fine-grained theoretical as well as holistic approach can contribute to balance perspectives and support the development of transition practices (Kyndt et al., 2017).

To conclude, the research presented in this section highlights a central challenge for migrant students, i.e. the realization and recognition of the value of their competences and abilities which are now not incorporated in the set of skills that seem to be required to participate in and complete mainstream higher educational programmes. There is, however, a glaring lack of research that focuses on how such a deficit perspective varies and impacts on students’ educational pathways in terms of transitions and participation in different disciplines and professional/vocational programmes (Mangan & Winter, 2017; Harvey & Mallman, 2019). Comparative studies that focus on educational landscapes in countries in Europe that have received large amounts of migrants over the past decades, are also scarce. Furthermore, a general concern raised in the literature is the epistemological and methodological issue of integrating different aspects that have an impact on students’ educational pathways and transitions to HE across analytical levels (Gravett, Kinchin, & Winstone, 2020). This article aims at contributing and filling this gap in the analysis of two datasets, where the intersections between policy and practice are scrutinized in a comparative study between Sweden and Italy.

In the remainder of the paper, section 2 discusses the vertical case study as the methodological approach. The results are presented in section 3. The study ends with a discussion of the results and their implications for the inclusion and integration of a diverse student population in higher education

The overarching issue that this study aims at taking onboard is to investigate the ways in which policy ideas are recontextualized in local sites of practice. To address this aim and the research questions we use a multi-sited (Marcus 1995), comparative approach to ethnographic studies of educational practices that is no longer bound to a specific “group” or a community, but, and in line with our take on diversity and identity outlined above, “reframes the basic unit of cultural analysis as processual and iterative” (Eisenhart, 2017, p.142), thus expanding the contextualization of ethnography to shed analytical focus on how policies, practices and institutionalized arrangements in one site, move and are entangled to other contexts and timescales. Bartlett and Vavrus (2014) called such an approach “vertical case study”, but they emphasise that the term “vertical” is a reminiscence of how they initially conceptualised the approach that now incorporates, besides the vertical, also horizontal and transversal elements of comparison.

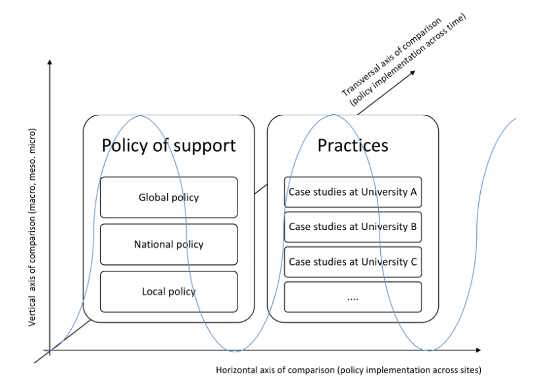

Figure 1: Illustration of the vertical case study approach

(adapted from Bartlett & Vavrus, 2014).

Given the aim of this study, such a comparative approach deals, on the horizontal axis (Figure 1), with a variety of contexts that includes case studies with students from the spaces of Sweden and Italy at selected universities. University A (UniA) and University C (UniC) are located in Sweden, while University B (UniB) is located in Italy. The transversal axis represents policy implementation across time and that, we argue, represents the dimension that may assist us in the endeavour to come away from research methods that, more or less exclusively, focus upon a particular singular group or population, to reframe interpretive logics and representational techniques as travelling “across time, space and level, rather than as the characteristics or lifeways of bounded groups” (Eisenhart, 2017, p.135). The data for the vertical case study outlined here was created through two complementary methods: analysis of policy of support (dataset 1) and case studies of three emblematic students from a broader dataset of 13 participants (dataset 2). The first method was employed to analyse policy content and its connection across levels and sites. The second method was used to analyse the students’ narratives of their lived experiences of transitions to HE. These methods used together allowed us to deal with micro and macro levels of analysis and to shed light on the relations across levels but also on their potential to engage with multiple spatial fields or sites, represented by the blue, waved line in Figure 1. Thus, the multi-sited ethnographies reported in this study offer means of examining the ways in which the participants in the case studies make sense of their transitions towards becoming university students when the conditions to achieve such transformations are constituted and constrained by their connection with policy, educational activities, support services, and technologies.

The policy of support (dataset 1) corresponds to the vertical axis of comparison (macro-micro). The analysis of dataset 2 connects the horizontal axes (policy implementation across sites) in terms of the analysis of students’ narratives of transitions and participation in higher education at their local practices (micro-level). The nature and process of data creation of the two datasets are detailed further in the next two sub-sections.

The nature of dataset 1, created using an ethnographic approach by means of connection across websites and documents, lends itself to envisage the analytical scaling model from macro to micro in terms of entanglements, rather than levels or layers. This logic also gives further fuel to the debate about the notion of analytical levels and on the kinds of (dis)advantages that it may bring, in relation to an alternative perspective according to which there are always macro aspects in the micro and vice versa (see e.g. Faubion & Marcus, 2009; Tsing, 2005). Dataset 1 includes a selection of the provision of support services in HE as it is framed and described in webpages and policy documents in a selection of national universities in Sweden (UniA) and Italy (UniB).

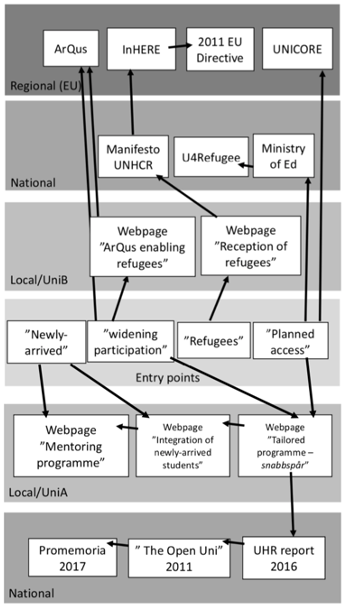

Figure 2. Vertical entanglement of policy. Overview of the

principal nodes and connections.

Figure 2 illustrates the entanglements from the first searches using a selection of keywords in the different webpages (e.g. the “Entry points” box in light grey). The illustration develops in two opposite vertical directions, starting from the Entry points box in the middle. On the top half, the path in the Italian data is represented, while the bottom half shows the principal nodes in the Swedish data. Figure 2 could be envisaged as an hourglass, of which the Entry points box constitutes the narrowest part. The metaphor of the hour glass also allows us to illustrate the vertical movement “across scales” as well as search words that have been a central aspect in a distillation process in terms of “an operation of extraction” (Marres & Weltevrede, 2013, p. 2019) that, we argue operationalises the process of creating representative and relevant data. Figure 2 represents different aspects of this process. Firstly, it shows the paths undertaken, from the first search words, to the documents found in the searches. Secondly, it is an illustration of the tensions that exist in the attempt to present different parts of the data according to a logic of scales, from micro to macro, or local to global, and vice versa. Figure 2 also visualises the results of the searches that will be presented in further details in section 3.1.

In dataset 2, we specifically draw upon data from two projects, led by the two co-authors in this study. Both projects focus upon students’ transitions to HE and consist of ethnographically generated data that build upon a case-study design (Middleton, 2018; Yin, 2018). The data includes audio recordings of informal discussions and interviews with 13 participants as well as document data in settings in the nation-states of Sweden and Italy. The data focused upon in this dataset includes three semi-structured interviews in particular, that were carried out with three participants for dataset 2, two in Sweden and one in Italy. The participants represent the breadth among the student group focused upon in this study (migrant and refugees) and two of them are students at the universities that were selected for the creation of dataset 1. Dataset 2 corresponds to the horizontal axis of comparison in the vertical case study approach, i.e. the comparison of policy implementation at the local level, across sites. The participants’ backgrounds range from recent asylum seekers, to students migrating in early childhood and those migrating as teenagers. The set of procedures that guided the analysis of dataset 2 were inductively oriented, and aimed at identifying “patterns across the dataset” (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Braun, Clarke & Weate, 2016). Firstly, we familiarized with the data by revisiting the transcriptions in several collaborative steps, as a reflective process, while ensuring to remain open to alternative patterns and in search of overlapping themes in the recorded interviews. This was followed by further refinements by critically approaching our initially suggested themes, and as a result of continued analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Braun, Clarke & Weate, 2016), we reached the results presented in section 3. The portraits based on the demographic parameters of the cases used in this study are spelt out below.

M, born in Turkey, is now in her mid 20s. M came to Sweden as a toddler. Though she has gone through the Swedish educational system, her parents were working, not aware of the expectations of parents to engage in supporting and encouraging children’s learning also from home. The parents’ level of education is very low, and according to herself, she comes from a so-called socio-economic exposed area. Her education path before entering university was marked by challenges, starting with the fact that she learned to read very late. She has been awarded a Bachelor degree in pedagogy, which was the programme that opened the door to university studies, but not her first choice. After M gained her Bachelor degree, she did not apply for a job, and, now more confident as a university student, she decided to continue her studies. At present she is finalizing her second Bachelor in the field of organization and staff development, focusing on human resources, with a strong foundation in sociology and human work science, at Uni C, Sweden.

F, who is now in her late 30s, was born in the Kurdish part of Iran. She came to Sweden at thirteen, after being smuggled across the border between Iran and Turkey, and was sent to Turkish prison for a period, as she was deemed to be an adult. F was brought up by her grandparents, while her father had immigrated to Sweden for political reasons. Due to her grandparents preventing her from attending the village school, F only had sporadic periods at school. F studied on her own at home, and took tests up to year six without her grandparents’ knowledge. In Sweden, F was placed in a preparation class for a short time, and then placed in a class according to her age and not based on skills. As F did not understand what teachers were saying, the years in secondary school were lost. After attending adult classes (upper secondary level) to get grades required for university studies, F applied for freestanding courses that were later compiled into a Bachelor degree in psychology, at UniA. After her Bachelor exam, F has worked at the Swedish Migration Agency for a couple of years, handling new migrants’ and immigrants’ applications, in particular due to F’s familiarity with Kurdish and Persian as her two first languages. At present she is finalising her master programme in public administration, management and guidance, at UniA, Sweden.

A is a 34 years old Syrian man, with refugee status who at the time was enrolled in the second year of studies at Political Science Bachelor degree at the Uni B, Italy. He had arrived in Italy after deserting the Syrian army and a transition period in Lebanon where he taught himself English and had found a way to relate to the wider world and to earn some money by teaching Arabic to English speaking people. In Syria, after secondary school, he had been forced to study computer science although it was not what he wanted to do. His secondary school marks did not allow him to study Political Science (his first choice) at university. Computer science was the only possible choice. He is a gifted storyteller, interested in writing with a focus on reporting about Syria. He supports himself by translating, teaching Arabic, and when necessary by working as a waiter. 2.3 Analysis across axes of comparison

A vertical case study approach presents a set of challenges in terms of producing (re)presentation of the results of the analysis that include important details that, put together, make a coherent whole. Another challenge has been to re-think the “global/local antinomy” (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2014, p.134) in order to become sensitive in our analysis about the ways in which policy gets its materiality not only through inscriptions, but also through encounters and practices. Finally, even our focus on a particular group and selected nation states has had methodological implications, in terms of moving away from clearly bounded research sites on the one hand, and using the same bounded notions of nation-states or specific named-groups, on the other. In order to attend to the complexity of the different dimensions in a vertical case study, not least in the use of two datasets, we used several techniques. We engaged with the analyses of datasets recursively, in that they shed mutual light to one another as the themes and interesting patterns were identified in the data. For instance, the analyses of selected chunks in the data were discussed in data sessions in relation to the ways in which they contributed to shed light on the different dimensions of a widening participation agenda in both countries, i.e. how they differed or overlapped. Thus, another important gap that this study aims at filling by this frontline mix-method approach is the one between the “official and local enactment [of policy] and the proliferation of unintended consequences” (Fenwick, Richard & Sawchuk, 2011, p.115). In addition, a key particular element of such a generative and collaborative process at a vertical level, across micro and macro, and at a horizontal level, across sites, was to inductively identify key overarching meaning patterns that were further screened through thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2019; Braun., Clarke, & Weate, 2016). The results of the analyses are presented in section 3, in two separated sub-sections, starting with the vertical axis of comparison and a focus on dataset 1 in section 3.1, to move to the horizontal axis and the analysis of policy implementation across sites in the narratives of our selected case studies in dataset 2, in section 3.2. The final section, 4, presents an overarching discussion and some implications that go beyond the nation-state focus of Sweden and Italy.

In this section, we present the results from the analysis of dataset 1, i.e. provision of support services for migrants and refugees. Focus lies on the vertical axis of comparison (macro-micro) starting from the “entry points” (see Figure 1) in the search conducted in each university. We start by presenting the result from the entry points in first UniA and then UniB across the different documents to trace their entanglements across scales and sites on the vertical and horizontal axes of comparison (see Figure 1 & 2).

3.1.1 UniA

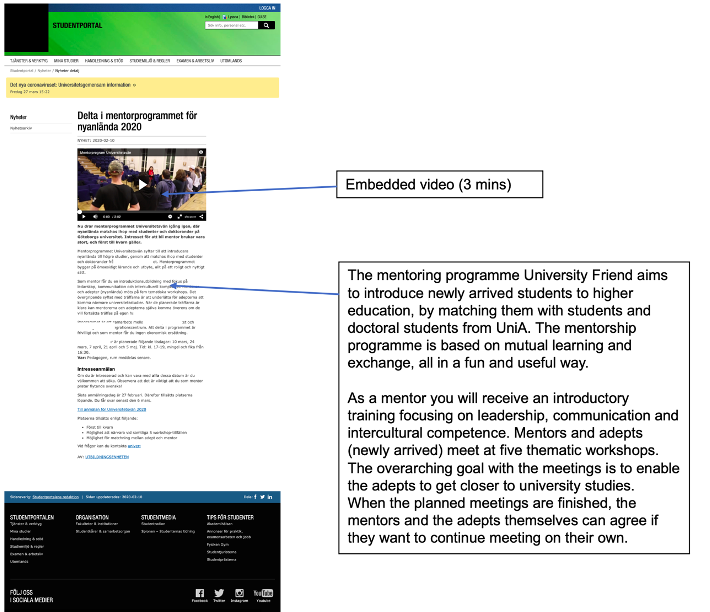

The analysis of UniA webpages shows that issues of access and inclusion overlap across different groups where the categories of “migrants”, “refugees”, “newly arrived” “asylum seekers” blend together and are not mutually exclusive in the Swedish data. Figure 3 is an illustration of one of the results from the entry points in the UniA searches.

Figure 3. University A. Capture of the full-size

screenshot of the website (left). Zooming in the central area of

the page (right). Translation from Swedish in the text box.

The page that contains information about a mentoring programme for newly arrived migrants (see Figure 3) is addressed to university students that have the opportunity, by participating in this programme, to support and guide the newly arrived students in their transition to HE. The students are matched with mentors who can avail of an introduction course during which they learn about leadership, communication and intercultural competence. The text also aims at making this event (that is offered regularly every term at UniA) and the role as mentor into something that many students aspire to participate in. Mutual learning is raised as part of the process for both mentors and “adepts”, but “på ett roligt och nyttigt sätt” (Sw:1 “in a fun and useful way”).

Another webpage at UniA provides information about initiatives for newly arrived and integration that imply a number of educational paths especially tailored for “utländska” (Sw: foreigners) and “nyanlända” (Sw: newly arrived). The common denominator of the ways in which such paths are presented in the documents is the use of formulations that put the spotlight on the orientation of such programmes towards specific groups and with a specific aim. For instance, the national programme for school and pre-school teachers especially targeting migrants and newly arrived are called “snabbspår” (Sw: fast track). Similar programmes for other professions imply that the applicant has a competence and/or a formal education from the country of origin that can be validated as the corresponding qualifications required to enter the programme according to mainstream Swedish requirements. This process is called “validering av reell kompetens” (Sw: Validation of actual competence) and is currently a much-debated issue in the higher educational landscape in Sweden because it puts the spotlight on the mainly pragmatic and instrumental view of competence, especially when it is related to a particular professional occupation. This is discussed in depth in the Swedish report by the Swedish Council for Higher Education (UHR): “Kan excellens uppnås i homogena studentgrupper”? (Sw: Can excellence be achieved in homogeneous student groups?) from 2016 (UHR, rapport 2016). In the UHR document (2016), universities are reported to have raised issues concerning the need for the establishment of a network with other authorities to allow “nyanlända” to rapidly enter HE. Thus, the issue of “speed” when it comes to migrant students transitioning in and out of HE is prominent in the Swedish data. One year after the publication of the UHR report (2016), the issue of widening participation (rather than only recruitment) was also included as part of national policy (Promemoria U2017/03082/UH), as a necessity for successful transitions across educational pathways. This implies a use of resources that take cognizance of the different functions in HE, from study counselling and the routines for evaluation of “actual competence” (see above) to the kinds of pedagogical efforts required in this endeavour. The 2017 Promemoria caused a vivid debate among university faculty in Sweden at the end of the same year and resulted in a cancellation of the proposition to change the formulation in the Swedish Higher Education Act from widening recruitment to widening participation.

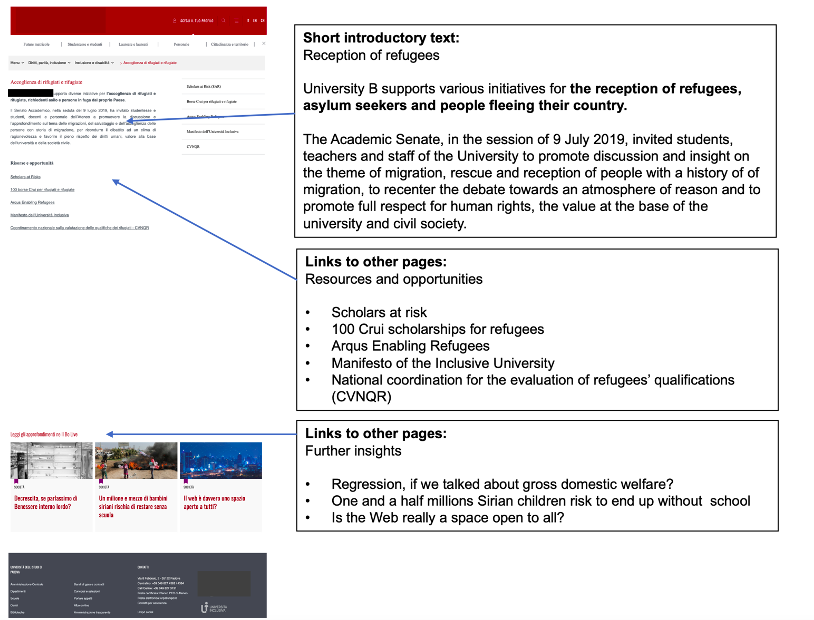

3.1.2 UniB

In the data from UniB (Italy) the page about inclusion for refugees can be accessed through a search in the university website using the term “refugees” (see Figure 2). The page about inclusion and reception of refugees is rather representative of UniB webpages: it provides a short framing text with a section called “Resources and opportunities” that includes a series of internal links to other pages (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. University B. Capture of the full-size

screenshot of the website (left). Translation from Swedish in the

text boxes (right).

These links lead to pages with information about, for instance, “Scholars at risk”, student scholarships, and the Manifesto for the Inclusive University2 (see also Figure 3). When entering the page about the Manifesto, words like “accoglienza” “diritti” “parità” and “inclusione” (It:3 welcoming, rights, equity and inclusion) are used to frame an agenda of inclusion, openness and widening participation in which “scuola e università offrono un'importante opportunità per i giovani rifugiati, rappresentando un passaggio fondamentale nel loro percorso di inclusione sociale”4 . According to this logic, the university (along with school) becomes the fundamental site where a “rite of passage” is made possible, from a status of “refugee” to “university student”. Once in this page, a link, embedded in the body of the text, leads the reader to a pdf document, where the official manifesto is presented. The text is a programmatic document and presents general principles and outlines that the universities that participate in it share a commitment to follow. Also in this document, that comprehends students, researchers and teachers with a refugee status, the terminology about hospitality, inclusion and integration dominates the text. Diversity is framed as the appreciation of cultural difference and as a source of academic enrichment for the university. The Manifesto ends with a quote to the Canto XVII in Dante’s Paradiso (Heaven) in the Divine Comedy. The chosen verses allude to Dante’s exile and the challenges of being forced to leave one’s home.

Tu lascerai ogne cosa diletta

più caramente; e questo è quello strale

che l'arco de lo essilio pria saetta.

Tu proverai sì come sa di sale

lo pane altrui, e come è duro calle

lo scendere e 'l salir per l'altrui scale.5

(Dante, Paradiso, Canto XVII)

The Manifesto contains a number of external links to other UNHCR documents, and the inHERE initiative (HE supporting Refugees in Europe) (www.inHEREproject.eu) that includes several longer documents, e.g. the Guidelines for university staff members 6 and the Good Practice Catalogue 7. The inHERE recommendations represent an international document that aims at providing general guidelines to the 29 participating universities in Europe. The “Good Practice Catalogue” focuses on a number of issues and challenges for an individual with a refugee status that aim at participating in the academic life as a student, teacher or researcher. Such issues include, for instance, support for recognition of previous degrees, “equitable and wide” access, financial support, language and bridging courses, integration, employment and employability, online learning, humanitarian work and collaboration among institutions and across sectors.

The section about access to HE links to article 27 in a EU directive (2011/95/EU) on standards for the qualification of third-country nationals or stateless persons as beneficiaries of international protection, according to which all EU member states shall provide the same conditions for access as third country nationals who are legally residents. Furthermore, the section explores further the issue of access and its boundaries, more specifically:

Granting equitable and wide access to higher education

involves more than providing tuition-free degrees, and a

multitude of diverse policy tools and institutional measures

exist for non-traditional or disadvantaged learners. In addition

to scholarships and financial support, measures may target

refugees via outreach activities, and also beyond recruitment to

provide general information to the potential refugee students

about the higher education system and its opportunities,

consulting them through mentoring programmes and helping them

navigate through the application procedures.

(https://www.inhereproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/inHERE-GPC_en.PDF.pdf

p.6)

Support to promote and grant access goes, according to this logic, beyond policy and financial support. Also, in the extract above, the refugee status is framed as belonging to another dimension that should be kept separated from the “ordinary” support for the inclusion of “non-traditional” or “disadvantaged” learners. Who these latter groups include more specifically is not clear in the document, but what makes the refugee status out of the ordinary is students’ need to be informed, guided and mentored to find their way in the intricate path of higher education, not least when it comes to the application procedures. Issues of inclusion and support are seemingly “differently special” for refugees as compared to other groups at risk of being marginalized. Such specificity for the status of a person who has been granted asylum, that was forced, against her/his will, to suddenly leave all that she/he cares for “to taste the bitterness of others’ bread” as the quote to Dante’s canto succinctly illustrates, is a rather prominent feature in the UniB data and the further documents at national and international level that have been accessed in the search process. This trend is also reinforced by the terminology used in the documents, irrespectively of the language variety (Italian or English), that effectively draws from semantic traits that allude to hospitality, generosity, openness, as gifts from the virtuous and prosperous donor to a person facing integration difficulties at different levels. The refugee is a person whose cultural and educational background should be welcomed, respected and elevated as a source of stimulating exchange and mutual learning.

To conclude, based on our comparison, the results of the analysis of dataset 1 sheds light on the different ways in which migrant students are framed as in need of support, mentoring, welcome, or other special arrangements specifically tailored for students who differ from the mainstream in the form of individuals who are purported to belong to a homogeneous, monolingual norm related to a nation-state. The virtuous character of the host country in UniB (Italy) in terms of hospitality and generosity is less visible in the Swedish data, and is instead replaced by a logic of efficiency and speed in the process, from reception to integration. Within the local higher education institution, as well as across universities and nation-states, the results show that different services and targeted programmes (addressing students’ mobility on one side, and students with a migrant background on the other) run the risk of creating parallel welcome and support approaches concerning student conditions that share the same “cultural diversity” core issue. The results also contribute to the discussion on the relevance of conceptualizing the study of diversity and of transitions to HE in scalar terms (global/local) (see also Enders, 2004). The emergence of global or supra-national policies like ArQus and InHERE, relates to a discourse of globalization and internationalization of HE (along with the idea of the migrant student as in need of special support), and offers insights on the patterns created by national governmental policies in the everyday lives of students. It is to shed light on this latter dimension that we move to the next result section of this study.

In this sub-section we present the results from the analysis of dataset 2, i.e. the interviews and discussions together with three students, two in Sweden and one in Italy. This dataset sheds light on the second question posed in this study, i.e. the investigation of the ways in which policy ideas about transition and widening participation are enmeshed in the students’ narratives and how they affect the students’ experiences of participation, normalization and marginalization in HE.

3.2.1 “Breaking the bubble”: transitions as conquering seemingly unreachable spaces

The transitional paths to higher education involved leaving previous familiar and local spaces, out of the comfort zone, to encounter and develop an understanding of mainstream norms that underpin studies at university level. To conquer these unknown spaces, a shift from the local and micro perspective, to a new context of individual growth, i.e. learning what this implied in practice, became a prerequisite for transitions. It is evident how previous patterns of participation in education affect and become entangled with how experiences of transitioning to higher education evolve over time, as illustrated in the narratives.

When M accounted for what it is like being a student at the university, she referred to her experiences when she first entered the Bachelor programme in pedagogy at UniA. At the time of applying, she was less sure about what to study, and just accepted the programme that she had put first on her ranking list. As she described herself as coming from a socio-economic exposed area, she attended secondary and upper secondary level in the same suburb, with the same people. The transition to university was a challenge in many ways. Her account illustrated the social and contextual boundaries, and how previous life trajectories impact transition to university. M and her friends decided to apply elsewhere to break the bubble. M mentioned her transition to university studies as something very big in her world, and that now she was a grown-up. This change also implied thinking about what she was saying.

Now it’s the university world, now think differently, behave maturely, maybe not say everything you are thinking. It was like entering a new identity, a new role. Now you need to present a façade that you don’t really want to from within.

Here it becomes relevant to frame M’s narrative in terms of “transition as becoming” (Gale & Parker, 2014, see also Biesta, 2016), i.e. as a transforming process of identity requiring the learning of “the rites of passage”, to adapt to and participate according to norms for participation as a student. These changes also impacted on M’s ways of being with others, and, in order to challenge herself, she made other decisions, to learn and develop as a person. In the case of M, the “breaking the bubble” experience, has given her self-confidence. It is evident in her account that such a transition for her, has meant to learn how to be as well as behave in accordance to the norms set for university studies, norms that have a high currency in terms of societal expectations and the ways in which she could handle different situations in her everyday life. At the beginning of her university studies, she went for people like her, to stay in a comfort zone with people sharing similar life trajectories as herself. University studies entailed placing herself in uncomfortable situations, and everything felt strange.

I felt as if I had come to an empty, it was like creating, finding a new empty sheet that I had to fill in, and start writing and shape this, be courageous and dare to be brave when being in uncomfortable situations that you will meet.

The notion of the “empty sheet” as a metaphor for emptiness that needed to be “filled” by education, is similar to the ways in which F described her own stance to transitioning, and being responsible for creating a space for her student identity.

I have learned what academic is expected to look like, you do not have to feel inferior in certain contexts, like I did before I started my studies at the university, when I was hired as a receptionist, where I noticed that people were thinking about me, you have no education, I was nothing to them.

The metaphor of “breaking the bubble” into a world that is partly concealed and surrounded by an aura of enchanting mystery is relevant to understand the kinds of shortcomings, mismatches and at times, absurd situations that our cases faced when dealing with transition to HE. Here, gatekeeping is a key aspect of this process as it means, for the students, to be able to see opportunities as well as who, what, where and when these can become accessible realities.

3.2.2 Gatekeeping - on possibilities, expectations, and ambitions to overcome “insurmountable barriers”

The processes of transitioning from previous education to enter an individual pathway through the university system, and with expectations of enrolment, were enmeshed with several unforeseeable challenges at a macro policy level. With less or little insight into university policy regulations, and gatekeeping enabled by existing structures, overcoming barriers, and crossing boundaries, were interdependent with encountering key persons who could support becoming a legitimate participant in higher education.

Starting with low grades from the upper secondary level, F met with difficulties when applying to the programme she was interested in, a Bachelor programme in psychology to which she was not admitted. Somebody informed her about the possibility of applying to freestanding courses that could be compiled into an exam later. F referred to this as her opportunity, an opportunity that also added extra stress during the whole study period, as she was not guaranteed a place in these courses. Each term, each course was framed by this uncertainty.

It would have been easier for me if I would have been admitted to the programme from the beginning. That would have reduced my stress during all terms, on my own trying to find out what courses I could apply to and keep my fingers crossed hoping to be admitted. This was the case for each course. It’s not that easy to be admitted to a programme when you don’t have a pass with distinction on everything .

Below, F referred back to her experiences working at the Swedish Migration Agency, to make sense of her own challenges to transition to higher education. F recalled the many accounts given by refugees and immigrants entering Sweden, and going through the required processes. F pointed to Swedish bureaucracy as seriously hampering conditions and as time-consuming.

The Swedes don’t like when they hear an immigrant say I want to study, I want to study, I want to have a good job and things like that. I feel as if they become envious at once, you have come here and you are not expected to, you are to work with some sh-t job, you are not expected to have a better job than us, or something in that direction.

F herself had experiences from this kind of attitude as well as hearing from immigrants she has met.

I have experienced this kind of feeling everywhere, not only linked to myself, when an immigrant has said I want to do this, and this, many Swedes often smile scornfully. Maybe that is also one reason why you don’t get help, it is not, people come from other countries, do not think about educating yourself, it is all about finding a job. That is what they want, not educate them.

Policies of inclusion and integration were here instantiated in F’s accounts of the ways in which she and other “immigrants” were faced with the normalized expectations wherein quick access to paid labour was the primary scope of any educational path, rather than individual growth. While this may be the aim and focus for other student groups, when pondering the possibility to start an academic programme of study, in the case of marginalized groups, the choice of the academic path seemed to obey a norm where practical gains, rather than preferences, dominated.

A similar issue, but with a different outcome, was present in the data from Italy and in the case of A, whose tertiary education records from Syria show that he attended a Computer Science programme. Such records are misleading and far less telling and relevant when compared with the informal education and professional competences that he recently acquired. Computer Science was not what A wanted to study at the university. According to the Syrian formal education system, A’s secondary school marks did not allow him to enrol into the Political Science degree at the University. Therefore, in order to pursue his studies further, Computer Science was the only possible choice. To A, Political Science and Media/Journalism were his passion and main drive, in relation to his studies. While escaping Syria and living in Lebanon, A taught himself English from scratch, mainly by watching YouTube videos. A developed his competences as teacher by using English to offer face-to-face, as well as online Arabic lessons. At the same time, he started to develop his skills as a journalist and translator. Thus, A’s set of competences that were developed through informal and nonformal learning, i.e. not to be found in A’s formal records, included his fluency in a range of languages as well as his experience as a teacher and journalist that were not recognized in the formal process of enrolment in a higher education programme, although they may be relevant features in A’s prospective study path and future career profile. However, although very long and difficult, the “processo di riconoscimento dei crediti formativi” (It: educational credits recognition process) eventually resulted in A’s enrolment in the Political Science programme in UniB.

Transitioning from a life pre-HE to in-HE implies several challenges and constraints, that include both existential and ontological dimensions as well as pragmatic and with immediate consequences for one’s quality of life. For A this concerned practical/logistical aspects of living and studying in UniB as well as aspects of academic and content organisation. The latter implied an understanding of the rationale behind the disciplinary composition of the Political Science Bachelor Degree course. UniB offered A to be tutored by another student during this phase. According to A, this peer support proved to be helpful.

When I applied, the tutor (from Morocco) helped me a lot, we became friends. The fact that he knows my language and he knows the rules is very useful. It helped me to understand what the study plan is. It is even more useful when he studies the same course.

For instance, for A it was hard to see the relevance of the enhanced role of the history area, especially history beyond contemporary and modern events. As a student with a Syrian schooling background this was an unexpected feature of the course. It was relevant to be able to talk about it and to be introduced to the rationale behind this curriculum choice by somebody who could speak “his language” and would understand A’s specific schooling background. The relationship between students’ multilingual competence and transitioning towards legitimate patterns of participation in HE was a recurrent theme in the accounts.

3.2.3 Overlooking multilingualism as a bridge for transitioning to HE

In spite of the European Commission’s multilingualism policy8 , now extended beyond the European languages and spatial borders to include multilingualism mirroring a society increasingly impacted by migration, there was little evidence in the narratives that indicated available local policy support practices for language support. On the contrary, the participants’ lived experience illustrated a lack of understanding at university level of the present systemic barriers and how these affected the conditions for studying negatively.

F, who said she lost several years of schooling, made frequent references to how language use in university studies was challenging. The references made to lack of linguistic capital necessary for being able to succeed, were distinguished by lack of support to develop these skills, as a constant feature of her lived reality as a student. To address this barrier, F developed strategies for how to cope with the advanced scientific language in the course literature by adopting online resources.

Often and most of us who come from these countries are not that good in English, we don’t have it with us. So, when you finally learn Swedish, you have problems with English as well.

What has helped me was that now there is Google Translate, so today there are more things around. I don’t think I would have managed if it was like when I came to Sweden, when these resources didn’t exist. I have hardly studied any English.

When F compared herself with fellow students, who had attended the Swedish school system, she reasoned about writing, and the higher demands she had to struggle with, and the strategies she adopted. F has been forced to put at least the double efforts into her writing, and she constantly has to remind herself about the different characters of assignments, and what is required from the different writing genres in the various assignment formats. The concrete strategy for handling the reading and understanding texts in English, became copy-and-paste in Google translate. F is aware of its shortcomings but she said that without this resource, she would not have succeeded. F’s experiences highlight a consistent barrier and constraint characterized in particular by their linguistic competence, which the migrants were unable to capitalize upon due to “insufficient pedagogical and relational approaches” (Harvey & Mallman, 2019). Furthermore, in their study, Harvey and Mallman (2019) highlight that the linguistic capital of new migrants is the “most difficult for [them] to realize the potential of, due to insufficient pedagogical and relational approaches within the institution” (p.10). Due to the different epistemological and ontological dimensions that are at the core of different disciplines and their traditions, our analysis shows that linguistic competence (along with other, so-called general competences), is related to the voice and tradition (in terms of expectations) of a discipline. In other words, different educational programmes and the variety of course subjects and tasks therein, put different expectations on students’ capability to use an academic language e.g. crafting an argument, applying specific, technical terminology and abstract concepts. While such expectations may seem to lie beyond other, so-called, general competences, such as transcultural sensitivity or critical and analytical thinking and proficiency in language production, is central to provide the students with the “right” tools for legitimate participation in terms of “learning to talk the talk” as Seedhouse succinctly puts it (Seedhouse, 2008; see also Lave & Wenger, 1991). In the field of language studies, neologisms like superdiversity and translanguaging (Vertovec, 2017, Garcia, 2009) have been introduced to acknowledge the totality of the linguistic repertoire of individuals, especially when dealing with Southern multilingualism, i.e. the kind of linguistic competences that are usually not recognized in institutions in the Global North. However, translanguaging has lately become a synonym of a pedagogical approach, more than an analytical construct (Pavlenko, 2018; Bagga-Gupta & Messina Dahlberg, 2018). This is in line with the invitation formulated by Olson (2003) to formal education institutions to re-consider the ways they mediate “between the formal institutions of society - law, government, economy, science - and the interests, beliefs, and intentions of persons” (p.285).

In UniB (Italy), A suggested that being able to study and perform the exam in English would help migrant students to better understand the textbooks and to stay on track with the exam schedule.

Luckily some professors have accepted to allow students to have their exam in English. Examples include professors teaching English, History of International Relations, History of Political Doctrines, Culture and Religion, Sociology. But most of the teaching materials are in Italian. It would be important to have handbooks in English as well.

The issue of the language of study is closely related to the issue of the pace and the grading of the study career.

In another case, a professor did not accept to have the exam in English although he would accept to do an oral exam. This is a step forward because even if I am able to study in Italian, I am very slow when I have to write in Italian so I am wasting time even if I know the answer (and therefore getting lower marks).

Holding an oral exam would be better than a written exam, according to A. Part of the rationale for opting for an oral rather than a written exam lies in the fact that writing the answers to the exam’s questions in Italian could be a slower process, even when the content of the answer is known by the student. To be “on track” and follow the programme of study in terms of, for instance, being successful to get the right amount of ECTS each academic semester is a constantly present dimension in the life of all students, but is especially the case when students have been granted support on account of their socio-economic status as newly arrived migrants.

3.2.4 What and who is framing the support? Academic support contradictions

While reasoning about ways into higher education and the support therein, M (UniC, Sweden) argued that more attention should be given to the individual, her or his context, to find options available or alternatives forward.

I value higher education a lot, but it doesn’t mean that it shapes your identity. It should not feel impossible to study, to me it was all about finding my way into studies. It is so multidimensional, it is not possible just to connect with having low grades, and this person cannot continue studies. Grades are not enough, you need a personal meeting.

M’s account pointed to potential students’ ways of navigating their way to university studies (see e.g. Farenga, 2018; Lopez Gavira & Moriña, 2015; MacFarlane, 2016) and the challenges on a formal, policy level when life trajectories and complexities found in transitioning to university studies do not take into account dimensions from lived realities, that diverge from the norm expressed in structures and regulations for access, and application processes as presented in the analysis of dataset 1.

One example of such a mismatching was provided by A (UniB, Italy) who recalled that during his first academic year he was entitled to have his meals for free in the University canteens. To do so he had to certify his low income. At the end of the academic year, he was asked to pay the money back because during that year he was not able to pass enough exams, i.e. the equivalent of 24 ECTS. As a result, in his own words:

I am paying the money back through several instalments. I paid for one part of it. Every 2-3 months I am paying part of it. I probably still owe 4-600 euros. I respect the rule.

This kind of support was made available when it was actually relevant to the student’s needs, but at a time (the very first year) when he was likely to be unable to comply with the conditions attached to the support that was being offered. These types of mismatches between the institutional attempt to provide support and the actual conditions of those who might benefit from such support, provide evidence of the need for HE institutions to acquire a more comprehensive and complex view of the condition of migrant students and to involve them in negotiating and defining more appropriate and viable ways to address students’ equality.

In the remainder of the paper, we will further discuss the issues that arose in the analyses of both datasets, as well as the pedagogical implications that may derive from the study of the entanglements of complex phenomena across analytical scales.

The aim of this study was to investigate the intersections between policy and practice in relation to widening participation and transitions to higher education in two European countries that have faced and are still facing challenges related to the integration and inclusion of students whose identity positionings are not in conformity with the mainstream. Furthermore, this study is an attempt to take a step further in finding relevant analytical paths as well as methodologies that may shed light on these phenomena by bringing together and juxtaposing macro and micro analytical levels. Focus has lied on the textures of practices (Gherardi, 2006) in which migrant students are entangled with in their everyday life as participants in HE. We have focused upon the analyses of two datasets, one including national and international policy in selected online webpages, and the other case studies that focus on three students, enrolled in three higher educational institutions in Sweden and Italy. A comparison of the ways in which the selected universities in the respective countries deal with the challenges connected to the recent wave of migration related to global crises, has been incorporated in a research design in which focus lies at the intersection of a number of dimensions, one stretching across nation-states (nationally and locally) and the other across analytical scales (macro and micro).

There are a number of reflections that we can make from the analyses carried out in this study. Firstly, higher education pedagogy in times of transition requires to meet the kinds of societal challenges related to an (higher) education for the masses (see e.g. Tight, 2019), as well as uncertain career paths and relevance especially related to diverse student cohorts. Secondly, what we have framed here under the common term of migrant students is not a homogenous group in either country. And, yet, services of “special” support for students are only available for those who can produce evidence of their status of belonging to named social groups, like refugees, newly arrived migrants, but also, more in general, students whose abilities do not conform with the current formal understanding of what a “normal student” may be. Thus, if we accept the theoretical argument that identity and diversity are dimensions of human life that are constantly fluctuating and related to historical and cultural understandings of what different labels are and may mean, what does that leave us with, in terms of the study of a complex assemblage like the university (Bacevic, 2019)? The problem of “one higher education for all” automatically implies the creation of parallel systems within the systems, or, also, alternative solutions for the inclusion of a wide and diverse student population. We argue that one important pedagogical implication for universities globally, is to reflect on their role in the purported “widening participation” agenda that takes into account its political dimensions at the macro level (in terms of policy and infrastructures) as well as the micro level (in terms of what is done in the classroom).

This study offers a substantial contribution to the research that attempts to analytically scrutinise processes of inclusion and marginalisation with a broad analytical gaze, that allowed us to analyse, among other things, a “Catch 22 situation”, i.e. of mismatch between the range of support, including policies of inclusion from educational institutions, and the actual needs and challenges that the individuals belonging to the group focused upon here, meet in their transition and participation in higher education (in two European countries) (see also Dangoisse, De Clercq, Van Meenen, Chartier & Nils, 2019; Dunwoodie et al., 2020). Furthermore, sociomaterial analyses like the one conducted in this study question the assumption that policy and standards developed at a national level and implemented in the local level have separated logics or that there exists “an ontological distinction between the scalar level of the local, regional, national and global” (Fenwick, Edwards & Sawchuck, 2011). The resulting image, thus, is far from sharp. Real problems, as Ingold (2018) succinctly puts it, seldom arise with a self-contained solution already inside them. Real problems have no solution. For instance, in our analysis of the Italian data, being granted free-meal vouchers during the first year of study, provided that the student completes a certain amount of ECTS, implies, rather than the solution to a problem of accessibility and equity, the creation of further issues, when the student, who was not in the position to complete the credits during the first year, must reimburse the costs of all vouchers. The problem of access to academic language is present in the analysis of both datasets in terms of a lack of formal support services. As an alternative to such a formal support, the students reported to use digital technology and internet access to find ways to eventually enter and participate in HE in legitimate ways. In the case of F, in Sweden, Google Translate was a crucial component for her to be able to compensate for a lack of support in the development of an academic language where a familiarity with English, as well as Swedish, constitutes an important dimension. Similarly, in the Italian data, A was able to learn English by himself, watching YouTube videos.

Furthermore, the analysis of policy ideas has also shown that the promotion of mobility (including social mobility) in HE, as it is framed in the two countries, has important consequences for the inclusion of marginalized groups and their transitions to HE. One important ideology that has clearly emerged in the analysis of the Swedish and Italian data is the notion of “speed”. Speed is here understood as the sine qua non condition for transitions for all students. It is especially present in the discourse about the inclusion of marginalized groups and, more specifically, for students with a diverse ethnic background, like newly arrived migrants and refugees. While the rhetoric around speed differs in the analyses of policy in the two countries, (being rather prominent and more straightforwardly presented in the Swedish data) it permeates the expectation of a widening participation agenda in both countries. Speed means to get swiftly enrolled in the “right” higher educational programme, in getting university ECTS, a degree and eventually a relevant job position. Getting everything “right” seems to be a rather prominent issue in the ways in which our cases have handled their transitions to HE, in terms of a “breaking the bubble” experience. According to this logic, the university becomes an enchanted place that has the potential to open up new possibilities that arise at the students’ horizon. Here, connection to key persons (often friends and/or peers at the university) that possess a practical knowledge about the most successful path towards inclusion and swift transitions to HE, was of paramount importance for all our cases in both contexts.

Practices of transitions from a life pre-HE to in-HE are related to the ways in which competences (both formal and nonformal) are acknowledged in policy documents and this is framed differently in the two countries. While in Sweden practices of recognition of informal competences, so-called “reell kompetens”, have been present for a long time, at least on the outset, within the scope to widen the recruitment to higher education, this feature was not present in the Italian dataset 1. The notions of “reell kompetens” (Sw: informal competence) and “crediti formativi” (It: formative credits) differ in that the former recognizes the informal dimension of the competence acquired, whether the latter does not. A declared policy of recognition of informal competence in Sweden, however, does not mean that higher education is automatically more open or that the process of the inclusion and recognition of these competences in the student formal records is without issues. As we have seen in F’s report, this is far from the actual situation for all students that lack formal credits or marks in their lives pre-HE. In fact, A eventually did manage to enrol in Political Science at UniB (Italy), albeit after a long process. In other words, standardized practices of recognition of previous competences (be them gained through formal education or not) are, in our analysis of both datasets and across countries, rather than the solution to the issue of widening recruitment and participation, the result of efforts to accommodate an ideology in which mobility and fluidity of individuals and ideas has high currency, especially in Europe after the Bologna agreement at the end of the 1990s. This is also related to issues of integration, wherein the understanding of diversity varies in the two contexts of this study: from openness as a result of generosity and humanitarian efforts, where diversity is welcome as a source of mutual enrichment (Italy); to openness as the necessary condition to create diverse groups in academia (Sweden) that will, in turn, reflect the makeup of society at large, where, according to this logic, diversity is the norm.

To conclude, the analytical argument that constitutes one of the central, frontline contribution of this study, is that, in order to shed light on the kinds of opportunities that arise at the students’ horizon, it is relevant to compare and understand the ways in which policy implementation and appropriation takes place in practice and across sites. However, one important result that emerged in such an endeavour is that the boundaries between these dimensions are not to be conceived as dividing membranes that clearly mark what is global and what is local, what is macro and micro, or what is labelled as belonging to one nation-state or another. Rather, the vertical case study approach used here has shown the complex entanglements of, for instance, policies of standardization, and the ways in which students make sense of situations in which such policies become practices of standardization in terms of, for instance i) standards in relation to what the students should deliver to pass a course and ii) standards of the support delivered to help the students to do so. Transitions and widening participation, and the challenges that these have entailed for the students, are, in other words, not only affected by policy, they are, in fact, produced by a policy of inclusion. Our analyses have confirmed and carefully illustrated the general discourse in policy where migrant students are individuals whose specific experiences make access to and participation in HE distinct for them (Perry & Mallozzi, 2011). This deficit perspective still frames the issue as a one-way “aid” relation between the higher education organization and the students in both countries. Our analysis suggests that alternative frames could become part of a more adaptable and sensitive approach to issues related to how to accommodate a diverse student population in HE. Such alternative frames include a shift in perspective that takes into account the students’ competences and (formal and nonformal) educational backgrounds in relation to their study and career plans. This could be achieved by including and analysing students’ autobiographical data to allow a better understanding of their communities of interest, transnational networks, and skills (see also Ünlüsoy & de Haan, 2020). This informal and nonformal curriculum indicates the importance for HE institutions to make available appropriate autobiographical and competence recognition and validation tools. Furthermore, being aware of such skills would offer university staff and faculty opportunities to find ways forward in the curricula’s international dimensions as well as to explore and to acknowledge potential contributions by migrant students to develop courses and assessment approaches across global and local dimensions.

1 Sw: = original in Swedish.

2https://www.unhcr.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Manifesto-dellUniversita-inclusiva_UNHCR.pdf

3 It: = original in Italian.

4It: school and university offer an important opportunity for young refugees, thus representing a crucial transition in their path of social inclusion. (Our translation)

5 It: You shall leave everything you love most dearly: /this is the arrow that the bow of exile shoots first. /You shall know the bitter (salty) taste/ of others’ bread, and know/ how hard a path it is to continuously/ descend and ascend others’ stairs. (Our translation)

6 https://www.inhereproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/inHERE_Guidelines_EN.pdf

7https://www.inhereproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/inHERE-GPC_en.PDF.pdf

8https://ec.europa.eu/education/policies/multilingualism/about-multilingualism-policy_en

ASRs Asylum seekers and refugees

HE Higher Education

InHERE Higher Education supporting Refugees in Europe initiative

UHR Universitets- och högskolerådet (Sw: Swedish Council for Higher Education)

UniA University A (Sweden)

UniB University B (Italy)

UniC University C (Sweden)

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

UNICORE University Corridors for Refugees project

Bagga-Gupta, S., Messina Dahlberg, G. & Winther, Y. (2016)

Disabling and enabling technologies for learning in Higher

Education for all: Issues and challenges for whom? Informatics,

3(21). DOI: 10.3390/informatics3040021

Bagga-Gupta, S., Messina Dahlberg, G., Vigmo, S. (2020). Equity

and social justice for whom and by whom in contemporary higher

education? Situated-distributed policies of inclusion/integration

in Sweden. Learning and Teaching. The International Journal

of Higher Education in the Social Sciences, 13 (3),

82-110. DOI: 10.3167/latiss.2020.130306

Bagga-Gupta, S. & Messina Dahlberg, G. (2018). Meaning-making

or heterogeneity in the areas of language and identity? The case

of translanguaging and nyanlända (newly-arrived) across time and

space. International Journal of Multilingualism, 15(4),

383-411. DOI: 10.1080/14790718.2018.1468446

Bacevic, J. (2019). With or without U? Assemblage theory and

(de)territorialising the university. Globalisation, Societies

and Education, 17(1), 78-91. DOI:

10.1080/14767724.2018.1498323

Bartlett, L., & Vavrus, F. (2014). Transversing the Vertical

Case Study: A Methodological Approach to Studies of Educational

Policy as Practice. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 45(2),

131-147. DOI: 10.1111/aeq.12055

Biesta, G. J. J. (2016). Good education in an age of

measurement: ethics, politics, democracy. London:

Routledge.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in

psychology, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2),

77-101. DOI: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive

thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise

and Health, 11(4), 589-597. DOI:

10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braun, V., Clarke, V. & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic

analysis in sport and exercise research. In B. Smith & A. C.

Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in

sport and exercise (pp. 191-205). London: Routledge.

Brown, M., G., Wohn, D. Y., & Ellison, N. (2016). Without a

map: College access and the online practices of youth from

low-income communities. Computers & Education, 92-93, 104-116.

DOI: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.001

Dangoisse, F., Clercq, M. D., Meenen, F. V., Chartier, L., &

Nils, F. (2020). When disability becomes ability to navigate the

transition to higher education: a comparison of students with and

without disabilities. European Journal of Special Needs

Education, 35(4), 513-528. DOI:

10.1080/08856257.2019.1708642

Dunwoodie, K., Kaukko, M., Wilkinson, J., Reimer, K., & Webb,

S. (2020). Widening University Access for Students of

Asylum-Seeking Backgrounds:(Mis) recognition in an Australian

Context. Higher Education Policy, 1-22.

Ecclestone, K., Biesta, G. & Hughes. M. (2010) (Eds.) Transitions

and learning through the lifecourse. London: Routledge

Eisenhart, M. (2017). A matter of scale: multi-scale ethnographic

research on education in the United States. Ethnography and

Education, 12 (2), 134-147. DOI:

10.1080/17457823.2016.1257947

Enders, J. (2004). Higher education, internationalisation, and the

nation-state: Recent developments and challenges to governance

theory. Higher Education, 47(3), 361-382. DOI:

10.1023/B:HIGH.0000016461.98676.30

EU Directive 2011/95/EU. Directive 2011/95/EU of the European

Parliament and the Council. Official Journal of the European

Union L337/10 EN .

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:337:0009:0026:en:PDF

Farenga, S. A. (2018). Early struggles, peer groups and eventual

success: an artful inquiry into unpacking transitions into

university of widening participation students. Widening

Participation and Lifelong Learning, 20(1), 60-78. DOI:

10.5456/WPLL.20.1.60

Faubion, J. D., & Marcus, G. E. (2009) (Eds.). Fieldwork

is not what it used to be. Learning anthropology’s methods in a

time of transition. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Fenwick, T., Edwards, R., & Sawchuck, P. (2011).

Emerging approaches to educational research. Tracing the

sociomaterial. London: Routledge.

Fox, A., Baker, S., Charitonos, K., Jack, V., & Moser-Mercer,

B. (2020). Ethics-in-practice in fragile contexts: Research in

education for displaced persons, refugees and asylum seekers. British

Educational Research Journal. DOI: 10.1002/berj.3618.

Gale, T., & Parker, S. (2014) Navigating change: a typology of

student transition in higher education. Studies in Higher

Education, 39 (5), 734-753, DOI: