Frontline Learning Research Vol.7 No. 2 (2019) 40

- 56

ISSN 2295-3159

aUniversity of Antwerp, Belgium

Article received 2 January 2019 / revised 19 March / accepted 18 April / available online 8 May

In recent years, the emphasis on interaction in data use has grown because of its potential to support individual teachers. However, in practice, teachers do not appear to interact widely in their use of data, either formally or informally. To gain knowledge of how sustainable data use interactions can be facilitated, this study investigated how formal data use in teams of teachers affects the teachers’ informal interactive data use. A survey provided insight into 72 teachers’ perceptions of data use discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action at formal team meetings. Subsequently, social network analysis of seven teacher informal data use networks revealed that teachers with more positive perceptions about formal data use become more active in their informal data use network. Within the problem diagnosis phase, this tendency is to generalize across the participating teams. The results of this study imply that, particularly to define problems and formulate actions based on pupil learning outcome data, it is necessary to ensure strong connections between teachers in formal groupings in order to affect their informal interactive behaviour.

Keywords: Data use; informal interactions, formal groupings; collaboration

To date, teachers are increasingly stimulated to use data (e.g. student data) to learn about and improve their practice. This emphasis on data use in education originated from the belief that data use objectivises educational decisions and contributes to more effective (changes in) instructional practices. The idea is that the systematic analysis and interpretation of different types of data can lead to school improvement (Campbell & Levin, 2008; Carlson, Borman, & Robinson, 2011).

Teachers often experience difficulties in the process of transforming data into knowledge and action (Datnow & Hubbard, 2016; Hubbard, Datnow, & Pruyn, 2014; Jimerson, 2014; Wayman, Midgley, & Stingfield, 2007). Therefore, the international literature has pointed to the important role of teacher interactions in data use. Interactions have the potential to provide teachers struggling to use data appropriately with the necessary support to accomplish the complex translation of data into decisions and actions (Bertrand & Marsh, 2015). Moreover, the belief has grown that data use interactions create an environment for teachers’ professional development (Vanhoof & Schildkamp, 2014).

However, the current situation regarding interactive data use among teachers gives cause for pessimism, for two reasons. First, the frequency of interactions matters for teacher learning (Penuel, Sun, Frank, & Gallagher, 2012). Yet, data use interactions are often limited in comparison with other forms of professional interaction, either in formally-established groups or on an informal basis (Farley-Ripple & Buttram, 2015; Hubers, Moolenaar, Schildkamp, Daly, Handelzalts, & Pieters, 2017; Keuning, Van Geel, Visscher, Fox, & Moolenaar, 2016). Second, interdependence among teachers facilitates learning. This implies that teachers interact from shared values and goals and that there is collective responsibility for pupils’ learning (Horn & Little, 2010; Moolenaar, Sleegers, & Daly, 2012; Stoll, Bolam, McMahon, Wallace, & Thomas, 2006). Nevertheless, if data use interactions occur, teachers are not likely to share responsibility with colleagues in data use, with the result that brief exchanges of information take place rather than powerful learning activities (Van Gasse, Vanlommel, Vanhoof, & Van Petegem, 2016; 2017). The aforementioned issues mean that the value of learning outcomes from data use interactions must be put into question (Van Gasse et al., 2016).

Despite the great emphasis on teacher interactions in data use, there is a need for research to establish how sustainable and effective data use interactions are cultivated. An opportunity in this regard may lie in the interrelation between formal and informal interactions. After all, it has been known that teachers seek stability in terms of the number of colleagues that belong to their personal networks in schools, particularly when it comes to data use (Van Gasse, Vanlommel, Vanhoof, & Van Petegem, 2017; Farley-Ripple & Buttram, 2015). Therefore, knowing each other and working together in formal data use settings may be an important facilitator for teachers’ informal interactions. For example, research has shown that teachers involved in formal subgroups are more likely to interact with those colleagues on an informal basis (Daly, Moolenaar, Bolivar, & Burke, 2010; Meredith, Van Den Noortgate, Struyve, Gielen, & Kyndt, 2017). However, what has remained underexplored up to now in the context of data use is whether it is simply the involvement in formal interactions that determines teachers’ informal interactions or whether what happens within those formal interactions can also contribute to teachers’ informal interactions. In other words, the question arises whether it is being familiar with colleagues that affects teachers’ informal data use interactions or the degree to which they feel that formal occasions facilitate the proper use of data. To fill this lacuna, the following research questions will guide this paper:

1. To what extent do teachers perceive that proper data use is accomplished at formal team meetings?

2. How do teachers’ perceptions of data use at formal team meetings affect their informal interaction-seeking behaviour with colleagues from the formally-constructed team?

This conceptual framework will first provide broader information and a theory of data use. Subsequently, it will describe (the merits of) teacher interactions in the context of data use and outline the relationship between formal and informal interactions found in the literature.

Data use is a way to manage processes within the school. The aim is to map school processes, to ensure that these processes are in line with school-wide goals and to use data to improve these processes (Barrezeele, 2012; Schildkamp & Kuyper, 2010). Therefore, many types of qualitative and quantitative data can be used (Hulpia, Valcke & Verhaeghe, 2004; Schildkamp & Kuyper, 2010).

Data use is a somewhat simplistic linguistic merger of ‘data’ and ‘use’. Effective data use is not only about ‘data’ and about ‘use’. It is a complex and sequential process in which data are transformed into information and knowledge (Coburn & Turner, 2011; Marsh, 2012). Therefore, data users need to run through different sub-processes to interrupt teachers’ tendency to jump from data to decisions (Schildkamp et al., 2016).

A lot of research distinguishes the phases of data discussion, analysis, interpretation and action (Gummer & Mandinach, 2015; Marsh, 2012; Schildkamp et al., 2016). However, teachers often struggle with the translation of data to classroom interventions (Gummer & Mandinach, 2015; Datnow & Hubbard, 2016). Therefore, we explicitly insert a phase of problem diagnosis in our conceptualisation of data use. In this study, the sequence of data use is one of discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action (Verhaeghe et al., 2010). This means that data first needs to be read and discussed. Subsequently, data must be interpreted correctly. Next, potential causes and explanations are hypothesised and checked in the diagnosis phase. Finally, teachers design and implement improvement actions (Verhaeghe et al., 2010).

The data use sequence appears straightforward in outline. Nevertheless, the literature has repeatedly shown that in practice complexity arises because the sequence of activities is often interrupted or teachers return to previous phases (Schildkamp et al., 2015; Marsh & Farrell, 2015). Moreover, activities within the different phases of data use cannot be considered identical (Schildkamp et al., 2016). It is essential to approach the concept of data use with sufficient precision and to take into account that different phases can imply differences in teacher behaviour. Therefore, we will explicitly distinguish between data discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action in this study.

The early research on data use indicated that it is a difficult process for teachers. The sequence (discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action) includes numerous potential pitfalls. For example, individual teachers become stuck in the interpretation phase of data use or have difficulty ascertaining where exactly pupils’ problems are located when analysing the data (Datnow & Hubbard, 2016; Verhaeghe et al., 2010). Therefore, more recently, an increasing emphasis has been laid on teacher interactions in the context of data use. The conviction has grown that teacher interactions are beneficial because they provide a supportive environment in which individual data use struggles can be overcome (Bertrand & Marsh, 2015; Hubers et al., 2017). Moreover, interaction in the context of data use has been identified as conducive to a professional learning environment for teachers (Vanhoof & Schildkamp, 2014).

The following sections will further delineate the relationship between formal and informal interactions. Thereafter, we will describe how social network theory will be used to explore this connection.

Informal teacher interactions are formed based on personal goals. Informal interactions can occur very systematically or ad hoc, but always on the initiative of one (or more) teachers without the central and external creation of a common mission (Blankenship & Ruona, 2009). As a result, informal interactions may become more formal on the initiative of teachers themselves, but may equally remain unstructured and ad hoc.

Despite the potential of informal interactions for teacher learning (Jones & Dexter, 2014; Kyndt, Gijbels, Grosemans, & Donche, 2016) , there has been limited research on informal interactions in the area of data use. The few studies to report on such interactions have shown that they are fairly limited (Farley-Ripple & Buttram, 2015; Van Gasse et al., 2017). In addition, the group of colleagues with whom teachers interact appears to remain relatively fixed. Teachers’ consult a similar (but smaller) pool of colleagues for data use purposes, compared to for their regular professional activities (Farley-Ripple & Buttram, 2015). This implies that teachers will not turn to specific colleagues with regard to data use (e.g. data use experts), but rather that they maintain a stable network for their different professional activities. This is also illustrated in their approach to the different activities within the data use sequence. Across the discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action stages, teachers involve the same colleagues; however, for the more complex phases (e.g. data use action), fewer colleagues are consulted and deeper interactions are established (Van Gasse et al., 2017). The facts that teachers seek stability in interactions with colleagues and that deeper interactions are not established with all colleagues imply that informal interactions may be of significant importance for sustainable and effective data use. Therefore, further insights are needed into how these interactions can be facilitated and the role of formal interactions in this regard.

Contrary to informal interactions, formal interactions are formed in function of a specific organizational goal instead of individual goals. This means interactions for which a common mission to use data is created externally. Generally, such interactions result in the construction of pre-structured work groups, in which team members are made responsible for the outcomes, or the division of labour is clearly explicated beforehand (Blankenship & Ruona, 2009). Common examples of such formal interactions are data use interventions that include the creation of a team of educators working on specific school-related problems in order to learn how to use data (Ciampa & Gallagher, 2016; Cosner, 2011; Keuning et al., 2016; Schildkamp et al., 2016).

Research has shown marked differences in how such teams work through the different phases of data use, in a sense that some teams reach deeper levels of inquiry than others (Schildkamp et al., 2016). Moreover, it is not the case that creating such formal group settings automatically leads to highly interactive groups; in fact, levels of interactions in formal data use groups remain limited (Hubers et al., 2017; Keuning et al., 2016). In addition, the distribution of knowledge from inside formal data use work groups to colleagues outside the teams appears to be scarce (Hubers et al., 2017). Thus, although formal groups have been widely implemented with the aim of facilitating interactions between teachers beyond those groups and facilitating school-wide data use, such formal interactions seem to fall short of this intention. Given the teachers’ wish for stability in data use interactions and the limited number of colleagues with whom they undertake the most intense data use interactions (Farley-Ripple & Buttram, 2015; Van Gasse et al., 2017), more knowledge is needed about the mechanisms mediating between formal and informal data use interactions. These insights are needed to better facilitate the connection between interventions using formal group settings and teachers’ informal interactive behaviour in data use.

Research into teacher interactions has already exposed some interconnections between formal and informal interactions. For example, research of Meredith and colleagues (2017) showed that being connected to formal subunits can, to some extent, facilitate informal interactions. In the findings of their study, teachers who were connected to the same subunit appeared to interact more often with each other informally. Similar findings were reported by Penuel et al. (2010), who concluded that teachers’ being connected in a formal structure (by grade level) were more likely to interact with each other. Other researchers have argued that formal groupings provide a specific focus for interaction and shape opportunities for interactions (Spillane & Kim, 2012; Spillane, Parise, & Sherer, 2011). Therefore, some formal groupings are considered to have more influence on teacher interactions than personal characteristics (Spillane, Hopkins, & Sweet, 2015).

However, the aforementioned studies pay insufficient attention to the impact of what happens within formal meetings on teachers’ informal interactive behaviour. The studies look at formal structures and group compositions to explain why informal interactions take place; yet, in the context of data use, we know that large differences in group processes may occur (Schildkamp et al., 2016). Moreover, even among teachers who are bounded to the same formal data use groupings, informal interactions can be scarce (Van Gasse et al., 2017). Therefore, greater insight is needed into whether teachers perceive that proper discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action of data takes place in formal team meetings as this might also explain their informal interactive behaviour within the same constellation of teachers.

The study was carried out in Flanders, the Dutch speaking part of Belgium. In Flanders, schools get autonomy over how they achieve the required educational standards (Penninckx, Vanhoof, & Van Petegem, 2011). The government does not impose central exams (OECD, 2014). Instead, schools themselves are responsible for developing strategies to meet the Flemish standards at the end of secondary education. Therefore, the Flemish government’s perspective on data use is quite improvement oriented. This is different to countries with a longer though more accountability oriented tradition in data use (e.g. the Netherlands, United States, United Kingdom). In practice, this implies that Flemish schools and teachers often primarily rely on their own data sources (e.g. tests, assignments, observations or portfolios) for data use purposes.

In this study, we will report on teachers’ use of pupil learning outcome data because this is an informative source of data for teachers to improve their practices and to evaluate whether or not pupils meet the Flemish standards at the end of secondary education. Pupil learning outcome data include cognitive outcomes (i.e. linguistic and arithmetic skills) as well as non-cognitive outcomes (i.e. attitudes, and artistic and physical education), and those data can be both quantitative (e.g. class tests) and qualitative (e.g. observations). This conceptualisation of ‘data’ is broader than often-used definitions which refer solely to cognitive output indicators (Schildkamp et al., 2012). As such, this study contributes to an enriched conceptualisation of ‘pupil learning outcome data’ that includes both cognitive outcomes (e.g., linguistic and arithmetic skills) and non-cognitive outcomes (e.g., attitudes, and artistic and physical education).

The study took place in the context of a project on the assessment of competences (d-pac.be). All ten schools involved in the project were asked to participate in this study. In each school, the target population were all teachers of the pupil group that participated in an assessment of writing competences in the aforementioned project, i.e. the fifth grade of an academic track in economics and languages (16- to 17-year-olds). In Flanders, these forms of teacher teams are temporary interdisciplinary groupings that are collectively responsible for pupils’ learning. Two to three times during the school year, the teams are obliged to discuss the pupils’ learning outcomes in a formal team meeting. In the last team meeting of the year, team members deliberate as to whether or not pupils will successfully complete their year.

This study will report both on teachers’ perceptions of data use at those formal team meetings and their informal interactive behaviour in data use within the same team. In order to answer the present research questions, quantitative data analysis has been combined with social network analysis. Both types of data were collected in the same online survey.

In this study, interactions will be studied by means of social network analysis. This method draws on social network theory, which uses the position of actors within a network to determine their access to resources (e.g. colleagues’ knowledge and skills in a broad sense) (Finnigan & Daly, 2012). Social network analysis approaches interactions with fine-grained information. It brings together information about both actors in an inter-action, which creates great depth of analysis.

There are three general elements present in inter-actions. The first is interaction-seeking behaviour. For example, in a data use interaction, Teacher A may ask Teacher B for advice. In this case, Teacher A is sending a connection (or a tie) to Teacher B. This is what in social network analysis is called a sent tie (or outdegree). In reverse, Teacher B may also ask the advice of Teacher A (or send a connection to A). From Teacher A’s perspective, this a received tie (or indegree). If Teacher A and Teacher B ask each other for advice, both teachers are sending and receiving ties from each other. Social network analysis calls them reciprocated ties (Borgatti, Everett, & Johnson, 2013). Although the different characteristics of inter-actions are explained by means of advice ties, social network studies have used a range of topics for interaction purposes (e.g. friendship ties, information ties, general professional ties) (e.g. Van Gasse et al., 2017; Daly et al., 2010; Moolenaar et al., 2012).

Social network analysis provides a means of explaining the different types of connections between teachers. For example, perceptions of data use at formal team meetings can be used to explain different types of ties. Given the present research questions, this study will explain teachers’ outdegree measures. This measure reflects the number of outgoing interactions or the extent to which they take the initiative in interaction with colleagues (Borgatti, Mehra, Brass & Labianca, 2009). In other words, it will provide insight into whether teachers become more active interactors in data use when feeling more positive about formal data use with the same colleagues. In the analysis section, the term sender effects will refer to the effect of teachers’ perceptions of formal data use on their informal interactive behaviour in terms of outdegree (Sweet, 2016). For example, a positive sender effect would mean that the more positive teachers are about formal data use, the more likely they are to initiate informal interactions within the same network (i.e. to have a higher outdegree measure).

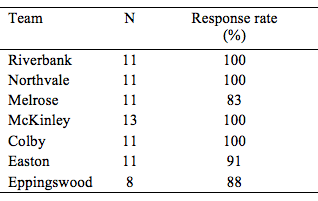

The data of three teams were excluded from this study because of a response rate lower than the 80% required in social network analysis. The other response rates are shown in Table 1. For confidentiality purposes, the team names are fictive.

Response rates above 80% were reached in all teams, with maximum response rates (100%) in four out of seven teams. The high response rates imply that accurate conclusions can be drawn about the relationship between formal and informal interactions in teachers’ use of pupil learning outcome data. Across the teams, 3048 data points provide sufficient statistical power to reveal some general tendencies.

Table 1:

Teams' response rates (social network analysis)

Apart from Team McKinley (13 teachers) and Team Eppingswood (8 teachers), the teams consisted of eleven teachers. The teams were interdisciplinary, which means that teachers teach different subjects to the pupil group. All teachers had a master degree; 60 % were female, 40 % were male. Further, a small majority of the participants taught the pupil group more than three course hours per week and the teaching experience of the participant group varied from less than five years to over thirty years.

Both teachers’ perceptions of their formal and informal data use interactions (i.e. the discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action with regard to pupil learning outcome data) were measured by using an online survey. First, some general information was questioned, such as gender, level of educational attainment or amount of teaching time per week in the specific pupil group (fifth year track economics and languages).

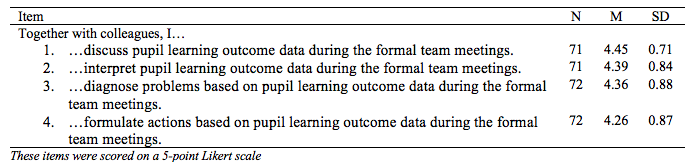

The second part of the survey included questions on the formal team meetings. Teachers were asked to rate five statements concerning the extent to which they use pupil learning outcome data at the formal team meetings (e.g. ‘Together with colleagues, I diagnose problems based on pupil learning outcome data during the formal team meetings’) on a scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). The Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 indicated good internal consistency of teachers’ perceptions regarding to the data use at these formal team meetings (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the formal interaction scale

In order to measure teachers’ perceptions of their informal data use interactions, social network questions were included in the survey. For each of the data use phases (i.e. discuss, interpret, diagnose, take action), a social network question was included (e.g. ‘Which of the following colleagues do you consult to discuss pupil learning outcome data?’). Subsequently, all members of the teacher team were listed and participants indicated which of the listed colleagues they consult for data use discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action apart from the formal team meetings of the team.

To answer the first research question, we aggregated teachers’ item scores of the five items on formal data use interactions at team level using SPSS 22 software. Subsequently, descriptive statistics (i.e. average and standard deviation) were calculated for each participating teacher team. As such, we are able to draw team-level conclusions about general perceptions regarding the use of pupil learning outcome data on formal occasions. This was necessary to build a point of reference for the informal interactive behaviour of teams that was analysed in light of the second research question.

With regard to the second research question, we first calculated a scale score (i.e. average score) of the five items on formal data use interaction at teacher level. This was needed for being able to attribute relational differences to individual differences and subsequently to team differences. The relation between teachers’ scale scores on the formal interaction scale and their informal interaction seeking behaviour was tested using Exponential Random Graph Modelling (ERGM). ERGM enables researchers to analyse interaction patterns in social networks and to explain specific relationships. This type of analysis predicts the presence of particular relations in the network and, thus, it can be used to assess the predictive value of teachers’ perceptions of interactions on formal data use occasions for their informal behaviour in networks. In doing this, ERGM takes into account global network structures As such, ERGM accounts for the multilevel effect that occurs in using the level of relationships (within individuals within teams) as the unit of analysis. Statnet’s R-based ERGM package was used for the analyses (Handcock, Hunter, Butts, Goodreau, & Morris, 2016).

ERGMs are specified at team level. Therefore, per team multiple ERGMs were specified; one for each phase of the data use cycle. Each of those ERGMs included a single sender effect for teachers’ scores on the formal interactions scale. This means that the model investigated whether higher scores on the formal interactions scale affect the probability of sending relationships (i.e. consulting colleagues). This effect was investigated in the different data use networks of each team (i.e. discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action). For each ERGM, the model with the sender effect included was compared with the baseline model by means of the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). This method was used to evaluate whether informal teacher interactions were better explained by teachers’ perceptions of formal interactions than by chance. To evaluate overall effects in the discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action networks, a meta-analysis was conducted across the seven teams using the ‘metafor’ package in R.

The structure of this section is aligned with the research questions. Therefore, we will first describe teachers’ perceptions regarding data use at formal team meetings. Then we will provide insight into the descriptive statistics with regard to teachers informal data use interactions in light of a better understanding of the subsequent analyses. Finally, we will present the findings on interrelationships between teachers’ perceptions of data use at formal team meetings and their informal data use interactions.

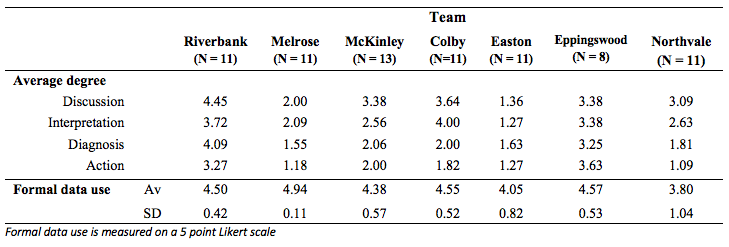

Table 3 provides an overview of the descriptive statistics of this study. The statistics with regard to ‘formal data use’ include the aggregated team scores of teachers’ perceptions of the use of pupil learning outcome data (i.e. discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action) at the obliged formal team meetings (cf. context description).

With regard to teachers’ perceptions of formal data use in the team, we find positive to strongly positive perceptions overall. In all teams, teachers report that pupil learning outcome data are discussed and interpreted at formal team meetings, that problems are diagnosed and that appropriate actions are formulated to improve pupils’ learning. Across the teams, averages range from moderately positive perceptions (average Team Northvale = 3.80) to extremely positive perceptions (average Team Melrose = 4.94).

However, in some teams teachers’ perceptions are more disparate than in others. For example, the standard deviation of Team Melrose indicates that all teachers answered the questions on formal data use similarly (SD = 0.11), whereas the same measure in Teams Easton and Northvale indicates a significantly larger variation between teachers (SD = 0.82 and SD = 1.04 respectively). This means that some teachers were a lot more positive than others about data use on formal occasions in those teams. The ERGM analysis will reveal whether such different perceptions also affect teachers’ informal data use interactions.

In order to better understand the interrelation between formal and informal data use interactions, Table 3 also shows the average number of informal interactions (i.e. interactions independent from the formal team meetings) within the discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action phase per teacher teams. This is represented by the ‘average degree’ measure, which refers to the number of outgoing relations (or the extent to which teachers consult colleagues), aggregated at team level.

We find limited informal activity within the teams across the data use sequence (discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action). Table 3 shows that the maximum average degree, for teams of 11 teachers, occurs in Team Riverbank’s discussion network (average degree = 4.45). This means that teachers in Team Riverbank are, on average, connected to 4–5 teachers (out of 10) for data discussion. Team Riverbank is the most active network of 11 teachers with regard to informal data use interactions. The smaller Team Eppingswood is interacting to a slightly greater extent compared to the other teams. For example, the average degree of 3.63 in the action network implies that teachers are interacting informally with 3–4 colleagues (out of 7). Furthermore, higher average degree numbers are found in team Colby, but only for the data discussion and interpretation networks; the established relations in the diagnosis and action networks of team Colby are in line with all other teams. Therefore, in general, informal data use interactions are scarce, with teachers connected to approximately 2 other teachers for informal data use discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action.

Table 3

Descriptive statistics per team

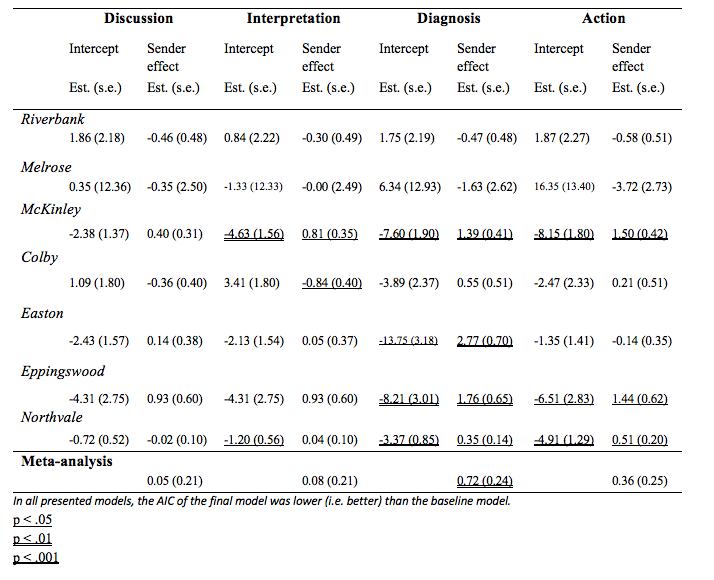

Table 4 shows the results of the ERGM analyses of the impact of teachers’ perceptions of formal data use on their informal interaction-seeking behaviour in data use. These effects are represented in the ‘sender effects’ columns. The different ERGMs provide an overview of the effects of teachers’ perceptions on formal interactions across the different phases of the data use sequence. As such, fine-grained conclusions on the effects of perceived formal interactions can be drawn.

A first finding of the ERGM analyses is that there are some teams in which there are no significant effects from teachers’ perceptions of formal data use on informal interaction-seeking data use behaviour. More specifically, teachers’ informal data use interactions in Teams Riverbank and Melrose cannot be related to their perceptions concerning formal data use in the same team constellations. In these teams, the teachers’ informal data use interactions can be explained equally well by chance. It is remarkable that Teams Riverbank and Melrose in particular show no significant effects from teachers’ perceptions of formal interactions on their interaction-seeking behaviour. As shown in Table 3, these are two of the four highest-scoring teams on the formal data use scale, which implies that teachers in those teams are particularly positive about the discussion and interpretation of data at formal team meetings, and about diagnosing problems and designing improvement actions based on data. Additionally, the aforementioned teams have smaller standard deviations in our sample, which indicates that the teachers gave similar answers on the formal data use scale.

Table 4

Sender effects of formal data use per team

In all other teams, the ERGM analyses show at least one effect. In Team Colby, we find a negative sender effect of formal data use on teachers’ informal interactive behaviour in the interpretation of pupil learning outcome data. In this team, teachers’ reporting higher scores on the formal data use scale are less likely to seek interaction with colleagues for the interpretation of pupil learning outcome data on an informal basis. In Team McKinley a significant sender effect is again found for data use interpretation. However, in this team the effect is positive. This implies that, in team McKinley, teachers who are more positive about the discussion and interpretation of pupil learning outcome data, and about diagnosing problems and defining improvement actions are more likely to consult their teammates for informal data interpretation.

Given this disparity of effects in the interpretation networks of these two teams, no significant generic effects across the teams were found in the meta-analysis. Together with the absence of effects in any of the teams’ discussion networks, this implies that no generic effects can be detected in the least complex phases of data use (i.e. discussion and interpretation). This implies that teachers’ perceptions of formal data use explain informal interactions for data discussion and interpretation no better than chance.

However, the ERGM analyses do show some effects of teachers’ perceptions of formal data use on their informal interaction-seeking behaviour in the more complex phases of data use. Moreover, in each of the networks, these effects are positive. In Teams Mckinley, Easton, Eppingswood and Northvale, teachers reporting higher scores on the formal data use scale are more likely to seek data use interactions with colleagues for diagnosing problems. This means that the more strongly teachers believe that pupil learning outcome data are discussed and interpreted effectively at formal team meetings, and that subsequently diagnosis is carried out and actions are defined, the more likely they are to consult (some of those) colleagues for informal data discussion.

With regard to the definition of improvement actions, we find similar effects in Teams McKinley, Eppingswood and Northvale. According to the network data, teachers with higher scores on the formal data use scale hare more likely to consult colleagues on data use actions. In other words, the teachers’ perceptions of data use at formal team meetings affect their informal interaction-seeking behaviour for the definition and implementation of improvement actions for pupils.

Thus, teachers’ perceptions of data use at formal team meetings seem to matter more for their informal interaction-seeking behaviour in the more complex phases of data use (i.e. discussion and action). The meta-analysis shows that these positive effects can be generalised across the teams for diagnosing problems from pupil learning outcome data, though not for defining and implementing improvement actions.

In data use, or the discussion and interpretation of data, the diagnosis of problems and the definition and implementation of improvement actions, researchers put a great emphasis on teacher interactions. Peer interactions can provide teachers with the support necessary to acquire the complex knowledge and skills needed to transform data into meaningful decisions and actions (Hubbard et al., 2014; Jimerson, 2014; Wayman et al., 2007). Given the context, in which changes in teaching practices sometimes require prompt action, informal data use interactions may be of particular importance for teachers. Nevertheless, the literature has shown that their informal data use interactions remain limited (Farley-Ripple & Buttram, 2015; Van Gasse et al., 2017). Therefore, it is crucial to understand how those informal data use interactions can be influenced. An important factor may be engagement in formal data use interactions. Research has shown that being active in formal structures affects informal interactions (Daly et al., 2010; Meredith et al., 2017). However, what remained under-researched was how teachers’ perceptions of (data use) activities within formal team meetings influence their informal interactive behaviour. The current study approached this lacuna using a combination of survey questions and social network analysis. As such, insight was provided into teachers’ perceptions of the use of pupil learning outcome data at formal team meetings and the influence of these perceptions on their informal interaction-seeking behaviour.

The descriptive statistics showed that, overall, teachers were positive about the discussion and interpretation of pupil learning outcome data at formal team meetings, as well as the diagnosis of problems and definition and implementation of improvement actions. There was notable variation in teachers’ perceptions across the teams, and some variation within them. The findings also showed limited informal data use interaction. On average, teachers were not connected to many of the colleagues with whom data use was carried out at formal team meetings. Nevertheless, drawing on the ERGM analyses, teachers’ perceptions of formal data use appeared be related to their informal interaction-seeking behaviour in the more complex phases of data use (i.e. diagnosis and action). Significant positive effects of teachers’ perceptions of formal data use were found on the extent to which teachers consult colleagues for diagnosing problems and defining and implementing improvement actions using pupil learning outcome data. However, these effects could only be generalised across the teams for the problem diagnosis phase.

Two findings were particularly remarkable in the results of the ERGM analyses. The first is that, in some teams, no significant effects were found. These teams (Riverbank and Melrose) had high average scores on the formal interactions scale with small standard deviations. This implies that teachers in those teams took a similar, positive stance towards the use of pupil learning outcomes at formal team meetings, making differences in informal behaviour more difficult to explain by this factor.

The second remarkable finding, which may represent a step forward in the field of data use interaction research, is that the impact of teachers’ perceptions of formal data use only appeared to have an effect on the more complex phases of informal data use (i.e. diagnosis and action). Apparently, a more or less positive stance towards the team’s formal data use is of less importance for teachers’ informal interaction-seeking at the data discussion and interpretation stages. Yet for informal interactions at the problem-diagnosis phase, teachers’ perceptions regarding data use at formal team meetings do matter. An explanation may lie in the fact that for data discussion and interpretation, teachers lay slightly less weight on the specific colleagues involved in their interactions. As prior research has shown, teachers use interactions in these phases to build a frame of reference (Van Gasse et al., 2016). Therefore, more colleagues may be suitable to interact with in these phases, and thus perceptions of what is happening at formal team meetings do not seem to play an important role. This is different in the phase of problem diagnosis and, to some extent, the phase of action. Within these phases, more specific knowledge is needed. In this regard, the use of pupil learning outcome data can to some extent serve as an example of problem diagnosis based on data. Positive perceptions of data use at formal team meetings can provide teachers with evidence that interactions in these phases may add value to the process of data use. Additionally, they may develop a sense of who, among their colleagues, would make interesting partners for diagnosing problems in data use. As a result, the impact of teachers’ perceptions of formal interactions on their informal interactive behaviour mainly manifests in the phases where teachers often struggle most (i.e. diagnosis and action). This implies that, when schools and teachers aim to arrive at fruitful data use, a pit of the matter may lie in facilitating teachers in thorough interactions to diagnose problems and formulate actions based on pupil learning outcome data at formal team meetings.

In line with previous research on data use interactions, this study showed limited teacher interactions (Farley-Ripple & Buttram, 2015; Hubers et al., 2017; Keuning et al., 2016). Previous research has also shown that teachers seek stability in their interactive data use behaviour. For example, teachers tend to interact with similar colleagues for data use and for their regular professional interactions (Farley-Ripple & Buttram, 2015). Furthermore, within the data use sequence (discussion, interpretation, diagnosis and action), teachers tend to select and retain a stable group of interlocutors (Van Gasse et al., 2017). In this regard, it is remarkable that this study reported a relatively low number of interactions between teachers. The colleagues involved in the social network checklist were all connected via formal data use occasions, thus informal interactions with these colleagues would have contributed to the stability of the teachers’ personal network.

Furthermore, research has repeatedly shown that data use cannot be considered a straightforward process because of the different sub-phases (Gummer & Mandinach, 2015; Schildkamp et al., 2016). Each of these phases require different knowledge and skills of teachers, and to some extent ‘a shift’ can be found between interpreting data and diagnosing problems and then taking actions in the knowledge that is used (Gummer & Mandinach, 2015). In teachers’ interactive behaviour, such a ‘shift’ has appreciable effects (Van Gasse et al., 2017). Therefore, the finding that teachers’ informal interaction-seeking behaviour may be influenced differently according to the data use phase, confirms and broadens this prior knowledge. In addition to contributing to the field of data use research, this study also broadens understanding of teachers’ interaction-seeking behaviour in general. This study is an extension of earlier work that related formal interactions to informal interaction-seeking behaviour (e.g. Meredith et al., 2017; Spillane et al., 2015). In those studies, formal groupings were related to interaction-seeking behaviour. The current study, however, adds to this knowledge in two ways.

First of all, it is not only the involvement in formal groupings that affect teachers’ informal interaction-seeking behaviour. This study shows the importance of what happens within these formal interactions. Thus, next to just being related by means of formal team meetings (e.g. Daly et al., 2010), teachers might only interact with their team members on an informal basis when they are positive about what happens at the formal team meetings.

The second aspect we learn on interactions in teacher networks is that the type of task may matter for the influence of formal interactions on informal behaviour. In previous work that shed light on the interconnection between formal and informal interactions, this aspect stayed somewhat under surface (e.g. Daly et al., 2010; Spillane). This study makes clear that this relation might be affected by teachers’ task, because effects were only found when the complexity of the task in front increases.

The social network approach taken in this study proved valuable for generating additional insights into how formal data use in team meetings can influence teachers’ informal data use interactions. However, there are some limitations to this study. The first is that the sample size was limited. Social network analysis requires intensive data collection because of the high response rates (over 80%) required. This because missing data can have a huge impact on the results. Suitable sample sizes are therefore difficult to obtain. However, for generalisable conclusions across the teams, the specificity of each team plays a role. For example, the fact that in teams Riverbank and Melrose no significant effects were found impacted on the way the findings could be generalised across the teams. This could have been resolved with a larger sample. Therefore, to generalise the findings of this study, larger-scale network research will be required. A second limitation of this study relates to the team context that was used. To define the boundaries of teams, we used the criterion of teaching a specific pupil group, which meant that the teachers in the formal grouping taught different subject areas. It is important to note that some teachers may feel closer connections to other formal groupings within schools, such as subject-related teams. Therefore, the present results are strongly context-depending based on the geographical situatedness in Flanders, but also based on the team boundaries. Therefore, choosing another formal grouping in future research may have an impact on the similarity of the findings to those in this study. The last limitation we want to emphasize is the limitations of using one survey-instrument. Therefore, we could not fully capture why we arrived at the present research results.

This study has generated some important implications for future research and practice. The first relates to the history of the formal team. The type of teams in this study might change about every school year. Therefore, the results of this type of analyses might be slightly different when focusing on formal teams with a longer history together (e.g. grade-level teams in the work of, inter alia, Meredith et al. (2017) or Spillane et al. (2015)). Replications of this study in other team contexts is necessary to fully understand how bounded the present results are to the current research context. Next, further studies might investigate the reasons that teachers are more interested in interacting with some colleagues rather than others in data use diagnosis and action. If, for example, we assume that teachers learn about each other’s strengths and weaknesses through formal data use interactions, do teachers seek out specific (and similar) colleagues for data use diagnosis and action on that basis? Thus, further research into whether, and why, specific teachers become more important in the complex phases of data use is essential for theory and practice. Certain information on general characteristics (e.g. age, experience) might be helpful in this regard. In addition, the fact that teachers’ perceptions of formal data use affect their informal interactions in the diagnosis (and action) phase warrants further exploration. More insight is needed into what exactly happens in formal data use interactions, how schools and teacher teams differ in those formal interactions and when and how those interactions affect teachers’ informal interactive behaviour. Opportunities in this regard can be found in combinations of social network analysis and qualitative data sources (e.g. observations or in-depth interviews) to further deepen the social network analyses of this study.

For the field of data use, this study brings about implications regarding the sustainability of the many interventions that are used to promote data use among practitioners (e.g. Ciampa & Gallagher, 2016; Cosner, 2011; Marsh, 2012; Schildkamp et al., 2016). Such interventions often introduce (new and temporary) formal teams to support schools in the use of data. This study shows that ‘getting to know each other’ is not sufficient for the sustainability of the data use interactions during the interventions. Such interventions might only succeed and grow into professional learning communities when sufficient attention is paid to how meaningful the data use activities are for the different team members. Therefore, it is important to ensure strong connections between teachers in formal groupings in order to encourage teachers’ informal interactive behaviour.

Blankenship, S. S., & Ruona, W. E. A.

(2009). Exploring knowledge sharing in social structures:

potential contributions to an overall knowledge management

strategy. Advances in developing human resources, 11(3),

290-306. doi: 10.1177/1523422309338578

Bertrand, M., & Marsh, J. A. (2015). Teachers' sensemaking of

data and implications for equity. American Educational

Research Journal, 52 (5), 861-893. doi:

10.3102/0002831215599251

Borgatti, S. P., Everett, M. G., & Johnson, J. C. (2013). Analyzing

social networks. Los Angeles: Sage.

Borgatti, S. P., Mehra, A., Brass, D. J., & Labianca, G.

(2009). Network Analysis in the social sciences. Science, 323,

892-895.

Campbell, C., & Levin, B. (2008). Using data to support

educational improvement. Educational Assessment, Evaluation

and Accountability, 21(1), 47-65. doi:

10.1007/s11092-008-9063-x

Ciampa, K., & Gallagher, T. L. (2016). Teacher collaborative

inquiry in the context of literacy education: Examining the

effects on teacher self-efficacy, instructional and assessment

practices. Teachers and Teaching, 22(7), 858-878. doi:

10.1080/13540602.2016.1185821

Coburn, C. E., & Turner, E. O. (2011). Research on data use: A

framework and analysis. Measurement: Interdisciplinary

Research & Perspective, 9(4), 173-206. doi:

10.1080/15366367.2011.626729

Cosner, S. (2011). Supporting the Initiation and Early Development

of Evicence-Based Grade-Level Collaboration in Urban Elementary

Schools: Key Roles and Strategies of Principals and Literacy

Coordinators. Urban Education, 46(4), 786-827. doi:

10.1177/0042085911399932

Daly, A., Moolenaar, N. M., Bolivar, J. M., & Burke, P.

(2011). Relationships in reform: the role of teachers’ social

networks. Journal of Educational Administration, 48(3),

359-391. doi: 10.1108/09578231011041062

Datnow, A., & Hubbard, L. (2016). Teacher capacity for and

beliefs about data-driven decision making: A literature review of

international research. Journal of Educational Change, 17(1),

7-28. doi: 10.1007/s10833-015-9264-2

Farley-Ripple, E. N., & Buttram, J. L. (2015). The development

of capacity for data use: The role of teacher networks in an

elementary school. Teachers College Record, 117(4),

1-34.

Finnigan, K. S., & Daly, A. J. (2012). Mind the gap:

Organizational learning and improvement in an underperforming

urban system. American Journal of Education, 119, 41-71.

Gummer, E. S., & Mandinach, E. B. (2015). Building a

conceptual framework for data literacy. Teachers College

Record, 117(4), 1-22.

Handcock, M. S., Hunter, D. R., Butts, C. T., Goodreau, S. M.,

& Morris, M. (2016). Statnet: Software tools for the

statistical modeling of network data (Version 2016.9).

Horn, I. S., & Little, J. W. (2010). Attending to problems of

practice: Routines and resources for professional learning in

teachers’ workplace interactions. American Educational

Research Journal, 47(1), 181-217. Doi:

10.3102/0002831209345158. doi: 10.3102/0002831209345158

Hubbard, L., Datnow, A., & Pruyn, L. (2014). Multiple

initiatives, multiple challenges: The promise and pitfalls of

implementing data. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 42,

54-62. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2013.10.003

Hubers, M. D., Moolenaar, N. M., Schildkamp, K., Daly, A.,

Handelzats, A., & Pieters, J. M. (2017). Share and succeed:

The development of knowledge sharing and brokerage in data teams’

network structures. Research Papers in Education, 1-23.

doi: 10.1080/02671522.2017.1286682

Jimerson, J. B. (2014). Thinking about data: Exploring the

development of mental models for data use among teachers and

school leaders. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 42(2014),

5-14. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2013.10.010

Jones, W. M. & Dexter, S. (2014). How teachers learn: the

roles of formal, informal, and independent learning. Educational

Technology Research and Development, 62(3), 367-384. doi:

10.1007/s11423-014-9337-6

Keuning, T., Van Geel, M., Visscher, A., Fox, J.P., &

Moolenaar, N.M. (2016). Transformation of schools' social networks

during a data-based decision making reform. Teachers College

Record, 118(9), 1-33.

Kyndt, E., Gijbels, D., Grosemans, I., & Donche, V. (2016).

Teachers’ everyday professional development: Mapping informal

learning activities, antecedents, and learning outcomes. Review

of Educational Research, 86(4), 1111-1150. doi:

10.3102/0034654315627864

Marsh, J. A. (2012). Interventions promoting educators’ use of

data: Research insights and gaps. Teachers’ College Record,

114, 1-48.

Marsh, J. A., & Farrell, C. C. (2015). How leaders can support

teachers with data-driven decision making: A framework for

understanding capacity building. Educational Management

Administration & Leadership, 43(2), 269-289. doi:

10.1177/1741143214537229

Meredith C., Van Den Noortgate W., Struyve C., Gielen S., Kyndt E.

(2017). Information seeking in secondary schools: A multilevel

network approach. Social Networks, 50, 35-45. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2017.03.006

Moolenaar, N. M., Sleegers, P. J. C., & Daly, A. J. (2012).

Teaming up: Linking collaboration networks, collective efficacy

and student achievement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28,

251-262. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2011.10.001

OECD (2014). TALIS 2013 Results: An international

perspective on teaching and learning , TALIS, OECD

Publishing, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264196261-en.

Penninckx, M., Vanhoof, J., & Van Petegem, P. (2011).

Evaluatie in het Vlaamse onderwijs. Beleid en praktijk van

leerling tot overheid . [Evaluation in Flemish education.

Policy and practice from student to government]

Antwerpen-Apeldoorn: Garant.

Penuel, W. R., Riel, M., Joshi, A., Pearlman, L., Kim, C. M.,

& Frank, K. A. (2010). The alignment of the informal and

formal organizational supports for reform: Implications for

improving teaching in schools. Educational Administration

Quarterly, 46(1), 57-95. doi: 10.1177/1094670509353180

Penuel, W. R., Sun, M., Frank, K. A. & Gallagher, H. A.

(2012). Using social network analysis to study how collegial

interactions can augment teacher learning from external

professional development. American Journal of Education, 119(1),

103-136.

Schildkamp, K., & Kuiper, W. (2010). Data-informed curriculum

reform: Which data, what purposes, and promoting and hindering

factors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(3), 482-496.

doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.06.007

Schildkamp, K., Poortman, C. L., & Handelzalts, A. (2016).

Data teams for school improvement. School Effectiveness and

School Improvement, 27(2), 228-254. doi:

10.1080/09243453.2015.1056192

Schildkamp, K., Rekers-Mombarg, L. T. M., & Harms, T. J.

(2012). Student group differences in examination results and

utilization for policy and school development. School

Effectiveness and School Improvement, 23(2), 229-255. doi:

10.1080/09243453.2011.652123

Spillane, J. P., Hopkins, M., & Sweet, T. (2015). Intra-and

inter-school interactions about instruction: exploring the

conditions for social capital development. American Journal

of Education, 122(1), 71 -110.

Spillane, J. P., & Kim, C. M. (2012). An exploratory analysis

of formal school leaders’positioning in instructional advice and

information networks in elementary schools. American Journal

of Education, 119(1), 73-102. doi: 10.1086/667755

Spillane, J. P., Parise, L. M., & Sherer, J. Z. (2011).

Organizational routines as coupling mechanisms policy, school

administration, and the technical core. American Educational

Research Journal, 48(3), 586-¬619.

Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S.

(2006). Professional learning communities: a review of the

literature. Journal of Educational Change, 7(4),

221-258. doi: 10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8

Sweet, T. M. (2016). Social Network Methods

for the Educational and Psychological Sciences. Educational

Psychologist, 51(3-4), 381-394. doi:

10.1080/00461520.2016.1208093

Vanhoof, J., & Schildkamp, K. (2014). From ‘professional

development for data use’ to ‘data use for professional

development’. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 42,

1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2014.05.001

Van Gasse, R., Vanlommel, K., Vanhoof, J. and Van Petegem, P.

(2016). Teacher collaboration on the use of pupil learning outcome

data: A rich environment for professional learning? Teaching and

Teacher Education, 60, 387-397. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.07.004

Van Gasse, R., Vanlommel, K., Vanhoof, J. and Van Petegem, P.

(2017). Unravelling data use in teacher teams: How network

patterns and interactive learning activities change across

different data use phases. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67,

550-560. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.002

Verhaeghe, G., Vanhoof, J., Valcke, M., & Van Petegem, P.

(2010). Using school performance feedback: perceptions of primary

school principals. School Effectiveness and School

Improvement, 21(2), 167-188. doi:

10.1080/09243450903396005

Wayman, J. C., Midgley, S., & Stringfield, S. (2007).

Leadership for data-based decision making: Collaborative educator

teams. In A. B. Danzig, K. M. Borman, B. A. W. Jones & W. F.

Wright (Eds.), Learner-centered leadership: Research, policy

and practice (pp. 189-205). New Jersey, USA: Lawrence

Erlbaum Associates.