Frontline Learning Research Special issue Vol.8

No.5 (2020) 24 - 46

ISSN 2295-3159

aUniversity of Education Upper

Austria, Austria

bUniversity of Hohenheim, Stuttgart, Germany

cUniversity of Bamberg, Germany

Article received 11 June 2018 / revised 3 May 2020 / accepted 7 May / available online 1 July

Research in moral education demonstrates the pattern referred to as happy victimising (HV) does not emerge only among children. Adults also transgress moral rules and might feel good doing so; however, research reveals the HV pattern emergence is context specific. In contrast to findings among young children in whom the HV pattern was interpreted as a lack of motivation and thus a developmental stage, it is an open question as to what happy victimising in adulthood means and how such patterns affect intentions as an important step towards action. This paper offers an action-theoretical approach, allowing for reconstruction of the process of intention formation, as well as a systematic discussion of results from two separate lines of research: (1) research on patterns of moral decision-making, such as the HV, and (2) research on moral disengagement. Additionally, a survey study provides insights into what intentions, emotion attributions, and moral disengagement strategies adults display in situations of low moral intensity, and whether they indicate consistent or contradictory patterns across situations. Results indicate intra-personal consistency regarding patterns of moral decision-making, but also show there are participants who vary these patterns across situations. Moral disengagement strategies were shown to have context-specific use, at least in regard to their subcategories. Regarding education, this study encourages not only a focus on strengthening the moral self or autonomous moral judgement but also on paying attention to actions and person-situation interactions. This might be useful to implement environments that support reduced application of moral disengagement strategies.

Keywords: Moral transgression, Happy Victimizer, moral acting, moral disengagement

The frequency of economic scandals, such as Diesel-gate, tax evasion, corruption, fraud, or fake-shops for breathing masks during the COVID-19 pandemic indicates that even people who seem to be friendly and empathic at first glance may transgress moral rules almost as frequently as others, depending on the situation, context, or one’s role. At least occasionally, people do not follow conventional rules, moral standards, or principles and, simultaneously, ignore others’ perspectives in favour of fulfilling their own or their companies’ needs. While this may lead to the assumption that moral transgression and self-centeredness are a basic human phenomenona that emerge in adulthood, research also shows that moral education can be successful in developing socio-moral competencies (e.g., Lind, 2019; Weinberger & Frewein, 2019) and creating a moral atmosphere. Further, fostering empathy and social perspective-taking helps to increase prosocial behaviour (Bandura, 2016; Eisenberg, Fabes, & Spinrad, 2007; Malti et al., 2016). From an educational perspective, it seems important to keep searching for effective ways to develop the competencies adults need to effectively deal with morally relevant situations in their everyday (working) lives. In routine as well as odd situations, people have to balance their own interests with those of others. Thus, to discuss aims of moral education across the lifespan, results of empirical research should be considered that contribute to explaining how people act, what personal and situational factors determine whether someone acts in line with or contradictory to moral standards, and how such competencies can be developed up to adulthood and beyond.

Research on moral psychology shows that agents simultaneously know about moral rules and attribute positive emotions in cases of transgression. This pattern of ethical decision-making, here called ‘happy victimising’, was initially detected among children approximately four years old; however, recent research has shown that this pattern also emerges among adolescents and adults (e.g., Heinrichs, Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, Latzko, Minnameier, & Döring, this issue; Heinrichs, Minnameier, Latzko & Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, 2015; Nunner-Winkler, 2007; 2013; Minnameier, Heinrichs, & Kirschbaum, 2016; Minnameier & Schmidt, 2013). Furthermore, there is evidence of different manifestations of ethical decision-making and emotion attributions, such as the patterns of

These patterns are at least applied in economically relevant situations, and emerge to varying extents, depending on the measurement methods used (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger & Latzko, this issue). They also vary intra-personally across situations, and can influence individual actions (Döring, 2013; Gasser, Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, Latzko, & Malti, 2013). Thus, these patterns of ethical decision-making might contribute to explaining adults’ deviant behaviours within different social, private, and work-related contexts. However, there is a lack of empirical evidence and theoretical foundations on how internal patterns of decision-making, moral judgments, and emotion attributions can be modelled to determine the processes of action in morally (and economically) relevant situations. This is important to study across different developmental stages; however, this article focuses on adults’ patterns of moral decision-making and emotion attributions as indicators of the valence of intentions, and thus as predictors for actions.

To bridge the gap between judgment and action, we applied the process model of judging and acting (Heinrichs, 2005). This model provides a theoretical framework to gain deeper insight into relevant situational and individual determinants of action processes. This model further offers a detailed reconstruction of the action formation process, from interpreting a perceived situation to implementing a behaviour. Particularly, it provides ideas on relevant steps in the first phase of acting, which concludes with intention formation. Referring to this process model, one obstacle to forming a high-valence intention is a lack of self-commitment to one’s preferred way of behaving. This lack may often become apparent in situations with conflicting values or goals, or when an individual perceives ambivalence in cognitive or emotional states, and often appears in UV and UM patterns.

To overcome this lack of commitment and form a high-valence intention, the process model posits that people use cognitive control strategies (Heinrichs, 2005). To specify what cognitive control strategies might be helpful in morally relevant situations where the agent has to choose between transgressing against or obeying a moral rule, it is necessary to refer to further research. Therefore, we refer to Bandura`s concept of ‘moral disengagement’ strategies (MDS; Bandura, 1990, 2016). Bandura and colleagues suggest (volitional) control strategies, and indicate that these strategies deactivate self-sanctions that would normally support moral action. Individuals using MDS can thus make a choice other than the ‘moral’ course of action, as these self-regulation strategies enable agents to reach a state of emotional well-being while causing negative (severe) consequences for others (Osofsky, Bandura, & Zimbardo, 2005). In specifying the role of MDS in the process of forming an intention, however, it remains questionable whether and to what extent people really apply MDS in certain situations; when they decide for or against a moral transgression; and whether they feel committed to choosing ‘victimising’ or ‘moral behaviours’. Focusing on MDS in particular situations seems important, as moral reasoning, moral emotions, and patterns of moral decision-making vary intra-personally across situations, and can therefore be considered results of person-situation interactions.

Therefore, it might be fruitful to study how people use MDS within the context of moral transgressions. Bandura and colleagues mainly studied MDS as individual tendencies across situations; thus, they looked for intra-personal consistency. Contrastingly, we focused on the application of MDS in particular situations during the action process, particularly during the first step towards acting: the sub-process of forming an intention. We aimed to provide deeper insights into whether individuals who intend to make moral transgressions (UV, HV) also apply MDS. If they use MDS in terms of (moral) reasoning for their preferences, in line with the process model, it could be assumed that MDS might have functioned during the process of forming intentions towards a preference of moral transgression, increasing the level of commitment, and the probability of acting in line with one’s intention.

Thus, this paper provides theoretical ideas and the first empirical data on the HV pattern in adulthood, exploring MDS use in morally relevant situations. Theoretically, the presented study refers to an action-based approach (Heinrichs, 2005) that allows for the presentation of theoretical ideas on how patterns of moral decision-making and emotion attributions (HV, UV, HM, UM), as well as MDS, may affect intentions in morally relevant situations, and specifically in situations that provoke decisions to follow or break a moral rule. The results of this questionnaire study among students can provide insight in differences in intentions, attributed emotions, and frequency, as well as qualities and intra-personal differences, of MDS use across morally relevant situations in a work-related context.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2.1 provides basic information on the state of research in terms of empirical findings on patterns of moral decision-making among adults. In this context, a rationale is provided for why this study focuses on situations of low moral intensity that are assumed to provoke victimisation at a higher rate than dilemmas and that are omnipresent in everyday (working) life. Section 2.2 explicates basic assumptions of an action-theoretical approach to reconstruct patterns of moral decision-making as potential intentions to act in morally relevant situations. We therefore chose situations in consumer and business contexts, as adolescents and adults are familiar with these situations in everyday or working life. Furthermore, such situations might have the potential to elucidate inner conflicts related to transgressing against moral rules in favour of economic or personal interests. Section 2.3 explains theoretical foundations and empirical findings related to MDS and posits that MDS may represent cognitive strategies that can be linked to intentions to obey or transgress against a moral rule. Based on this theoretical foundation, a survey study was conducted to explore whether and to what extent students apply patterns of moral decision-making and emotion attributions across situations, as well as whether and to what extent students use MDS when choosing whether to victimise others (Sections 3 and 4). Finally, implications for further research on decision-making, behaviour, and disengagement in morally relevant situations and implications for moral education are discussed (Section 5).

The developmental psychologists Nunner-Winkler and Sodian (1988) coined the term ‘Happy Victimizer Phenomenon’, and explained it as a lack of moral motivation at an early stage of moral development. As the rate of people displaying this ‘Happy Victimizer Phenomenon’ decreases in later age groups (from eight years onwards), it was assumed that this pattern is caused by the absence of a link between cognition and emotion, and therefore might be overcome during later stages of moral development (Krettenauer, Malti, & Sokol, 2008; Nunner-Winkler, 1993). However, further studies revealed that such patterns also emerged to a considerable extent in adolescence (Döring, 2013; Heinrichs et al., this issue) and even in adulthood (Heinrichs et al., 2015; Nunner-Winkler, 2007; 2013; Minnameier, Heinrichs, & Kirschbaum, 2016; Minnameier & Schmidt, 2013).

However, empirical studies have revealed that these patterns of moral decision-making in adulthood do not characterise a person-specific method of moral judgment, applied consistently across situations, with hardly any exceptions, as was assumed in the ‘Happy Victimizer Phenomenon’ of early childhood. Moreover, in adulthood, these patterns are described as varying intra-personally across situations, to an extent that had not been expected based on previous theoretical assumptions. Simultaneously, recent findings indicate a significant small or medium effect that still points to personal preferences towards patterns of moral decision-making (Heinrichs, et al., this issue; Malti & Krettenauer, 2013). Thus, patterns of moral decision-making seem to result from person-situation interaction, but are more affected by situational determinants than developmental psychology had assumed. Moreover, empirical research in moral and developmental psychology has previously confirmed that the proportion of moral decisions reflecting the HV pattern varies depending on situational cues, particularly on the degree of the moral conflict, or whether people are encouraged to make judgments using a self- or others’ perspective (Keller, Lourenço, Malti, & Saalbach, 2003; Nunner-Winkler, 2013; Malti & Krettenauer, 2013). However, these situational variations were mostly discussed as being dependent on measurement methods (Heinrichs et al., 2015; this issue; Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger & Latzko, this issue; Nunner-Winkler, 2013).

Following empirical results on intra-personal variations in moral decision-making, in this paper, we do not use the term ‘Happy Victimizer Phenomenon’, as previously described as emerging in earlier stages of childhood development. Moreover, we differentiate ‘patterns’ of moral decision-making and emotion attributions (see above; Heinrichs et al., this issue). It has been assumed that HV—as well as UV, HM, and UM—displays intra-personal variations in moral decision-making and managing moral emotions across situations. However, until now, there has been no satisfying empirical evidence supporting this, but rather a need for research on the personal and situational determinants that trigger the use or intra-personal change in these patterns. Furthermore, there is also a lack of theoretical approaches to explain HV in adulthood.

However, there is evidence that these patterns are important insofar as they are linked to individual actions. Empirical findings confirm that HV is a relevant pattern in the context of bullying (Gasser et al., 2013), and characterises bullies or bully victims. Moreover, the HV pattern is related to deviant adolescent behaviour (Döring, 2013). Research on counterproductive behaviour in organisational contexts indicates the relevance of individual moral values, judgments, and moral sensibility (Moore, Detert, Treviño, Baker, & Mayer, 2012). Thus, patterns of moral decision-making, such as HV, UV, HM, and UM, might further contribute to explaining deviant behaviours among adults, within different social, private, and work-related contexts. Therefore, they may also be relevant from the perspectives of moral education, vocational education, human resource development, and organisational behaviour.

This paper primarily contributes to theoretical progress in explaining determinants of the action process in morally relevant situations and, in particular, determinants of moral intentions. Therefore, two lines of research are linked to each other: research on patterns of moral decision-making, like the HV pattern, and research on MDS. The process model of acting (Heinrichs, 2005) functions as a theoretical framework which can be used to reconstruct and specify the action processes, from constituting a situation to forming an intention, implementation, conduct, and evaluation. This model was developed as a theoretical framework integrating Esser’s (1996) social psychological model of ‘definition of the situation’ and Heckhausen’s Rubikon model (Gollwitzer, 1996; Heckhausen, Gollwitzer, & Weinert, 1987), and is based on a set of assumptions. It allows for analysing the interaction between personal and situational determinants on the way from perceiving selected situational cues to forming an intention and behaviour (see Figure 1). Thus, in line with approaches to moral judgment and action in the post-Kohlbergian tradition, it does not focus on the development of personal determinants, but points to applying patterns of decision-making, reasoning, or acting to morally relevant situations and contexts (Krebs & Denton, 2005; Lapsley & Narvaez, 2005; for a summary, see also Heinrichs, 2010).

Figure 1. The Process Model of Acting: From Constituting

a Situation to Forming an Intention (Heinrichs, 2005)

The model’s basic assumptions are as follows (Heinrichs, 2005):

Regarding patterns of moral decision-making (HV, UV, UM, HM), forming an intention is the first of four phases in the action process. If a person has experienced a morally relevant problem (defined as a subjectively perceived gap between is and ought), then this individual might perceive a tension between obeying a moral rule and fulfilling his or her personal needs, and between different aims or actions. He or she might experience an ambivalence between cognitive, emotional, or motivational states, particularly if he or she attributes negative emotions towards his or her preferred way of behaving (UV or UM). If the person perceives an inner conflict, he or she might not yet feel committed to one aim or action. To form an intention and progress into action, he or she must then decide among alternatives. Referring to action theory, cognitive control strategies, in the sense of volitional strategies, play a major role in increasing commitment (Heckhausen, 1987; Heinrichs, 2005; 2013; Sokolowski, 1993; 1996). Volitional strategies support dealing with inner conflict or ambivalence in such a way that, finally, a state of commitment to one out of several possible actions could be achieved. In relation to patterns of moral decision-making, this means that the person feels committed to obeying or transgressing against a moral rule. It is assumed that such a state of self-commitment can only be reached if the individual anticipates being able to cope with upcoming negative consequences or conflicts.

As research shows that patterns such as HV emerge depending on the quality of a moral conflict, it can be assumed that there is a need to apply cognitive control strategies across situations that might vary according to the extent of moral intensity. A situation’s moral intensity depends on how an individual perceives elements of reality (see Figure 1; for more details on the concept of moral intensity, see Jones, 1991). Facing some ‘situational’ prompts, individuals may experience (intense) internal conflicts and high moral intensity. This could be expected, for example, in moral dilemmas that studies in moral psychology—especially in the Kohlbergian tradition—focused on, and that are supposed to seldomly emerge in everyday life. Contrastingly, situations of low moral intensity are assumed to be more frequent. Individuals perceive low moral intensity if they do not recognise an internal conflict, or if they quite easily make a decision towards one preferred action. Many people may perceive low moral intensity, for example, when transgressing against a moral rule only has (mild) negative consequences such as increased economic costs or treating others slightly unfairly, rather than causing physical or psychological harm.

In line with the process model of acting, we may assume that if people experience an inner conflict, forming an intention might be a matter of reflective (vs. intuitive) data processing. In moral conflicts and situations of high moral intensity, an individual might perceive a need for self-commitment and apply cognitive control strategies. Conversely, in situations of low to moderate moral intensity, an individual might experience a smaller difference between is and ought. People may display tendencies towards one action or another more easily and intuitively, based on automatic (cognitive and affective) processes of moral motivation (Haidt & Craig, 2008; Heinrichs, 2005; 2013; Rothmund & Baumert, 2014). However, even in cases of less conscious modes of data processing in which an individual has a clear preference for an action, for example in situations of low moral intensity or situations the individual has faced before, cognitive control strategies are assumed to play an important role in building commitment.

Taking situations of low intensity into account in research on moral actions may be important from an educational perspective. One possible scenario is that people who choose victimising in situations of low moral intensity may become used to it or even continue to transgress morally, even in situations of moderate or high moral intensity. Contrastingly, people who accept victimising in situations of low moral intensity might switch to obeying moral rules in situations of higher moral intensity. However, studying the development of HV and its determinants is an important question for further research and not the aim of this paper. Therefore, these considerations encouraged us to study patterns of moral decision-making in situations of low moral intensity as a first step and a matter of moral sensibility (Thoma & Bebeau, 2013; Tirri, 1999).

Thus, the process model of acting theoretically allows one to specify the role of cognitive control strategies as part of forming an intention. It is also assumed that intentions may differ in valence, that is, in strength of commitment or in their volitional power. Further, the volitional power of one’s intentions impacts how barriers need to be overcome during the implementation phase (Heckhausen et al., 1987; Heinrichs, 2005).

However, the process model of acting is first limited to theoretically reconstructing a sequence of input and output of inner sub-processes. Admittedly, an individual cannot be conscious of these psychological processes; instead, it is assumed that the individual is at least potentially aware of the content or results of subprocesses, such as intentions, emotion attributions, or cognitive control strategies, applied in a particular situation (Nisbett-Wilson-Thesis; see Neuweg, 1999). Thus, identifying relevant content or output of subprocesses, as mentioned above, could serve to systematically develop hypotheses concerning the links between them as results of subprocesses of actions in certain situations, such as the thesis that people who decide to victimise others and feel happy may have applied control strategies and deactivated self-sanctions, particularly regarding a specific situation.

Moreover, the process model of acting does not provide concepts specifying different kinds or qualities of cognitive control strategies; however, self-regulation theory does. The concept of MDS (Bandura, 1990; 2002; 2016) focuses on mechanisms people apply when choosing non-moral actions, such as transgressing against moral rules or victimising others. Thus, in this paper, MDS are chosen to specify mechanisms that supposedly support people in decision-making when experiencing internal conflict or ambivalence. Applying MDS may support the formation of intentions, even to engage in ‘immoral’ behaviours, such as moral transgressions or victimising others.

During the last two decades, MDS have been studied in various contexts (Bandura, 2016), including those related to situations of high moral intensity (e.g., McAlister, Bandura, & Owen, 2006) and lower moral intensity, such as in work-related contexts (Moore et al., 2012), sports (Boardley & Kavussanu, 2007), or connected to leadership issues (Detert, Treviño, & Sweitzer, 2008). Empirical findings reveal that MDS affect prosocial behaviours and transgressions in childhood, adolescence (Bandura, Caprara, Barbaranelli, Pastorelli, & Regalia, 2001), and adulthood (Detert et al., 2008; Fida, Paciello, Tramontano, Fontaine, Barbaranelli, & Farnese, 2015; Moore et al., 2012; Osofsky, Bandura, & Zimbardo, 2005). Research reveals that MDS as a personal trait impacts ethical and unethical behaviour in a wide range of morally relevant situations—not only in situations of high moral intensity, such as moral dilemmas, but also in situations of lower moral intensity (Moore et al., 2012). Bandura assumed that “self-sanctions keep conduct in line with internal standards” (Bandura, 1990, p. 28). Otherwise, “disengagement of moral self-sanctions enables people to compromise their moral standards and still retain their senses of moral integrity” (Bandura, 2016, p. 2). He differentiated four loci of MDS: locus of the behaviour, agent of action, outcomes of action, and recipients affected by action. Each of these loci indicates strategies allowing an individual to ignore moral standards and follow non-moral values (Bandura, 2016; Osofsky et al., 2005). The findings clearly indicate that MDS have the power to specifically explain unethical behaviour.

However, MDS are mostly measured by using a scale to understand the propensity as a trait or tendency to apply MDS in adolescence (Bandura et al., 2001), and an adapted version for adults (Moore et al., 2012). Findings have confirmed individuals’ propensity to use MDS as a predictor of unethical behaviour. Furthermore, Bandura reported that MDS was triggered by specific contextual factors (Bandura, 2002; Moore et al., 2012). Nevertheless, there is still a lack of insight into what type of MDS are applied in certain situations and whether MDS preference varies across situations.

According to the process model of acting as explained above, MDS might be particularly important in cases of ambivalence or conflicting aims or intentions. Additionally, MDS may affect forming an intention not only during reflective data processing but is assumed also to function as a filter in information processing when an individual intuitively commits to a non-moral action. An individual might make a decision based on heuristics, habits, or routines in everyday life, especially in cases of lower ambivalence and lower moral intensity, or when he or she does not have the opportunity to reflect, or accepts a suboptimal solution (Esser, 1996; Heinrichs, 2005).

Additionally, it can be assumed, in line with the MDS approach, that people with a high personal tendency towards MDS might develop a set of justifications consistent with their moral self, to manage internal ambivalence and conflicts in these morally relevant situations. MDS may function as cognitive control (or volitional) strategies and support forming an intention towards victimising or obeying moral rules. Thus, the application of MDS used in a particular situation may (sometimes) become visible if people are asked for the reasons behind their preferred actions.

To summarise, this paper offers theoretical approaches intended to contribute to explaining patterns of moral decision-making, such as the HV pattern, along with the process model of acting (Heinrichs, 2005) and the concept of MDS (Bandura, 2016). The theoretical considerations focus on a procedural perspective of acting, particularly on reconstructing how happy or unhappy people are who intend to break or obey moral rules and, thus, show patterns of intentions with varying valence. It is assumed that patterns of moral decision-making and emotion attributions represent results of processes determined by personal and situational conditions, and may vary interpersonally and situationally.

In addition to this theoretical approach to reconstructing the

HV pattern, this paper is intended to empirically explore whether

situational stimuli of low moral intensity may provoke

intrapersonal variation of HV or UV patterns across situations.

Moreover, it is intended to gain insights and explore whether and

to what extent adults apply MDS in given situations. The following

research questions are addressed:

(1) To what extent do adults apply victimising strategies in

situations of low moral intensity?

(2) Do patterns of moral decision-making and emotion attributions

among adults vary intra-personally across situations of low

intensity?

(3) To what extent do adults apply MDS to justify victimisation in

(different) situations of low moral intensity?

In total, 587 university students from Goethe University, Frankfurt (Germany; n = 201) and the University of Bamberg (Germany; n = 344) were surveyed using self-report questionnaires. Thirty-four students were guest students from other universities and eight students did not report their university affiliation. On average, students had studied in total for 3.3 semesters (SD = 1.8, Min. = 1, Max. = 12). Our sample comprised 213 male and 364 female students (10 students did not provide information regarding gender), with a mean age of 22.3 (SD = 2.9) years. Thus, participants were emerging adults. Of the observed students, 28.3% were studying to become teachers, 47.4% were studying economics, and 11.6 % were studying business education and educational management. Participant filled in a self-report, paper-and-pencil questionnaire. Questionnaires were provided in different university courses (e.g., educational psychology in the subject of teacher education studies, basics of scientific work, business ethics); thus, we used convenience sampling.

In the questionnaire, students were confronted with descriptions of morally relevant situations. The stimuli used in this study did not focus on extreme moral conflicts or dilemmas, such as the death penalty, but focused on situations of lower moral intensity that emerge in everyday life. Negative consequences of victimising others were limited to economic effects, such as high costs or losing money, or neglecting values relevant to social interactions, like honesty, trust, or legality. In the given cases, bodily harm or even death were not focused on as relevant consequences if the rule was disobeyed. Moreover, we were interested in whether adults deal with such situations of lower moral intensity using sophisticated heuristics, in line with MDS.

In response to open-ended questions, the students were asked to make decisions, anticipate their own emotions, and provide reasons for their decisions and emotions; more precisely, we asked for their intentions. This way of capturing the HV pattern has been described from a self-perpetrator perspective as “self-judgments” (Keller et al., 2003; Yuill, Pearson, Pearbhoy, & van den Ende, 1996; see also Heinrichs et al., this issue). Patterns of moral decision-making (here representing patterns of intentions) were coded (HV, UV, UM, HM). To explore whether cognitive control strategies, for example MDS, play a role in the action process, a content analysis of participants’ answers to open-ended questions regarding morally relevant decisions was conducted. The results are based on qualitative data (not the scale of MDS). Consistent with the concept of moral disengagement, data analysis was limited to participants who decided to transgress. Applying MDS is assumed to indicate perceived ambivalence, an output of moral decision-making in respect to selected situations. Moreover, this operationalisation of ‘applied MDS’ indicates that MDS play a role in the action process and intention formation, either before committing to a particular action, or afterwards to justify a previously made decision.

3.2.1 Patterns of Moral Decision-making

To identify the situation-specific patterns of moral decision-making in terms of HM, UM, HV, and UV, we used descriptions of two hypothetical situations of low moral intensity. In this study, moral intensity varied only regarding one criterion reported by Jones (1991): the quality of the relationship between perpetrator and victim. Other criteria that could potentially cause situations to be perceived as differing in moral intensity remained consistent across situations included in the survey. In Situation 1 (‘Travel costs’: an employee has to decide how to act confronted with the temptation to claim travel costs without having expenses), we chose a legal person (an organisation) as the victim, and in Situation 2 (‘Change’: a person receives to much change and has to decide to give the money back or not), we chose a natural person as the victim (for further description of the two situations, see the Appendix). HM, UM, HV, and UV were coded based on participants’ decisions as a relevant part of intentions. Participants answered the question ‘what would you do’ (give the money back as the moral strategy vs. keep the money as the victimising strategy; self-judgment perspective). Additionally, they rated their corresponding emotional state (‘How would you feel?’) by choosing one of the following options: very good, rather good, rather bad, or very bad. The ratings were re-coded as ‘happy’ (very good and rather good) and ‘unhappy’ (very bad and rather bad). Therefore, the HM pattern was operationalised by keeping a moral rule and feeling (very or rather) happy, and the UM pattern was defined by keeping a moral rule and feeling (very or rather) bad. Furthermore, the HV pattern was defined by violating a moral rule and feeling (very or rather) happy, and the UV pattern was defined by violating a moral rule and feeling (very or rather) bad.

3.2.2 Mechanisms of Moral Disengagement

In the context of moral decision-making, participants were asked to provide reasons for their decisions. On that basis, answers to open-ended questions were coded to organise the given reasons via a coding scheme for mechanisms of MDS, as adopted from the work of Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, and Pastorelli (1996). In line with the idea of MDS, only the answers of participants who decided to violate the moral rule (HV or UV) were considered. In total, the coding scheme consisted of the eight mechanisms of MDS and a category ‘others’, as described in Table 1.

The reported coding scheme was the basis for coding participants’ reasons for their decisions. The coding categories were a priori defined theoretically and coding rules were determined, thus constituting the theoretical basis of our analysis (Creswell, 2014; Schreier, 2012). Two independent researchers performed the coding. Both were well-trained with sample codes. Within a training round, the coders coded the participants' responses. When codes did not match, the respective sense units were discussed and assigned to a category by reaching a consensus. The category system was then further differentiated and validated. Thus, the coding procedure was guided by the standard procedure of qualitative content analysis as described Mayring (2015). To assess the inter-rater reliability of the coding, 64 reasons given by the participants (33 cases of Situation 1 and 31 cases of Situation 2), corresponding to almost 23 % of the overall applicable 280 cases, were coded by the two independent coders. Cohen's kappa score was 0.613 for the cases using Situation 1, and 0.713 for those using Situation 2. For all the 64 double-coded cases, Cohen’s kappa reached 0.7. Therefore, the situation-specific coding, as well the overall coding, showed satisfactory inter-rater reliability that could be classified as “substantial” (range from 0.61 to 0.8), according to the corresponding ranges of kappa with respect to Landis and Koch (1977). Cases coded in category ‘9 Others’ were discussed individually by two coders within consensus validation and, if possible, were assigned to one of the categories 1 to 8.

Table 1

Coding Scheme for Mechanisms of MDS

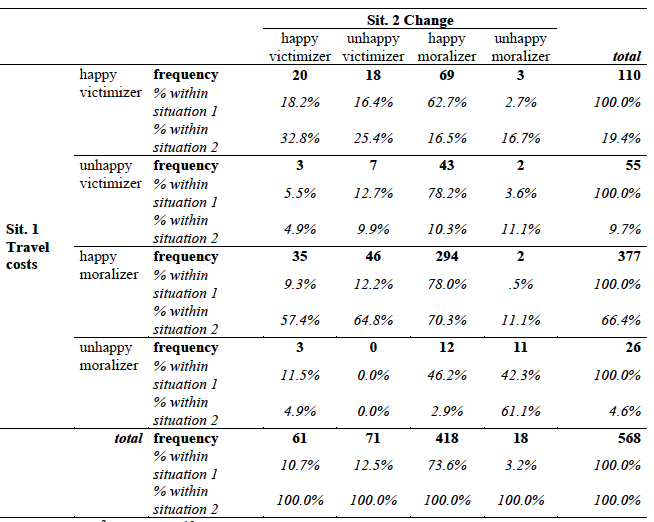

First, analyses were conducted to answer research questions 1 and 2. The results (see Table 2) indicated that all patterns of moral decision-making can be found in the sample. Most participants chose HM (Situation 1: 66.4 %; Situation 2: 73.6 %). However, 10.7 % in Situation 2 (n = 61) and up to 19.4 % (n = 110) in Situation 1 showed the HV pattern. Thus, victimising patterns can be applied in this sample of adults.

Table 2

Intra-personal Connections and Variations of Patterns of Moral Decision-making

Note. Pearson χ2 = 152.092, df = 9, p < 0.001; 19

participants had a missing value for at least one of the two

situations.

Regarding research question 2, Cramer’s V (0.299; p < 0.001; Pearson χ2 = 152.092, df = 9, p < 0.001) indicated a moderate-sized intrapersonal consistency of patterns of moral decision-making. However, there were participants who changed their pattern of moral decision-making across situations. For example, more than 25% out of students who rated HM in Situation 2 rated victimising in Situation 1.

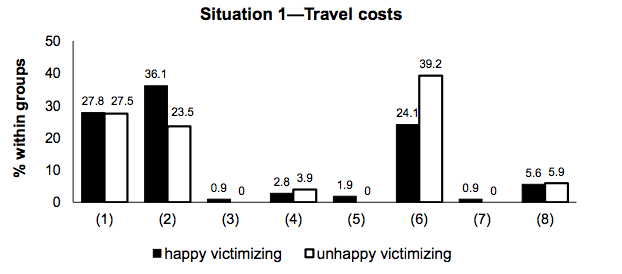

Along with the theoretical assumption of MDS, only those participants who chose victimising strategies were integrated into the content analyses to answer research question 3. The findings indicated that MDS were applied in the situations presented by those participants who chose victimising (Situation 1: n = 159; Situation 2: n = 111). Descriptive frequency analyses showed that all categories of MDS were used across both situations, though some mechanisms were not used in situations 2. However, frequency of the different MDS varied across situational stimuli (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Mechanisms of MD as Reasons for Violating a

Moral Rule: Situation 1—Travel Costs

Figure 3. Mechanisms of MDS as Reasons for Violating a

Moral Rule: Situation 2—Change

The process model of acting offers a framework to elucidate the role of cognitive control strategies, particularly MDS, to forming intentions towards following or breaking a moral rule in situations of low moral intensity. Further, it can provide theoretical progress and allows for a better understanding of patterns of moral decision-making and emotion attributions, such as HV, UV, UM, and HM (aims and valence), in morally relevant situations. Thus, this approach allows for the integration of perspectives of other theoretical approaches to HV in adulthood, as presented by Minnameier (this issue) and Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger and Latzko (this issue). The action-based perspective presented in this paper consider cognitive and emotional as well as volitional processes.

Additionally, the present study offers empirical results underlying the theoretical assumptions of the action-based approach to the HV pattern in situations of low moral intensity. The results related to research questions 1 and 2 merely support the findings of former studies regarding adults’ patterns of moral decision-making, as adults decided to victimise, and victimising emerged as a result of person-situation interactions. The patterns showed significant intrapersonal consistency; however, at the same time some participants showed variations in patterns across situations (Heinrichs et al., 2015). Moreover, the results of the present study enrich former empirical research on patterns of moral decision-making in adulthood, particularly by focusing on patterns of intentions in situations of low moral intensity. Additionally, MDS were assessed in the context of moral transgressions, not as a personal tendency. Qualitative content analysis provided codes of MDS within answers to open-ended questions, and showed that students who chose victimising applied MDS in the two given situations of low moral intensity, to a relevant extent. Frequency analyses of the different categories of MDS indicated that MDS use differed in quality and quantity across situations and between participants who attribute positive or negative emotions (between participants who show patterns of UV and HV; Figures 2 and 3). In future research, it could be interesting to collect data from a bigger sample to go beyond descriptive methods of analyses and test whether these differences in MDS use can be confirmed as significant effects triggered by situational conditions or as a personal tendency of MDS use.

However, the present study does not provide valid empirical evidence, but rather empirical insights regarding patterns of moral decision-making (UM, UV, HV, HM) and MDS use. Thus, our empirical approach obviously has various limitations that are discussed comprehensively, to point out the potential of the presented approach to gain theoretical and empirical progress in future research (Lakatos, 1978).

5.1.1 Limitations and Further Perspectives Regarding Methods and Data Collection

The present data were collected to examine to what extent moral decision-making, emotion attribution, and MDS use emerged as intra-personally consistent or varying across situations. Assuming that patterns of moral decision-making, as well as MDS use, are the results of person-situation interactions, only two situational stimuli were used for comparisons between different situational conditions. However, no personal determinants or traits were included to control for personal conditions. Thus, the results only allow for developing a hypothesis that patterns of moral decision-making might show up with intra-personal consistency, to a particular extent, while also indicating there is intra-personal variation across situations that has not yet been explained. Regarding MDS use, the results were mostly limited to a descriptive level. MDS use was coded based on the participants’ answers to open-ended questions, in line with the theoretical assumption that they would only be used if a person had also chosen ‘victimising’. That led to a reduced sample of the coded MDS: 159 participants for Situation 1, 111 participants for Situation 2, and only 32 participants who expressed MDS in both situations. Thus, this study does not provide reliable data on intrapersonal stability or variation of MDS use. Intra-personal consistent use vs. variation of MDS use across situations of low moral intensity should be studied in future investigations.

Additionally, the present study is limited to situations of low moral intensity, predominantly characterised as situations of temptation. Thus, the results do not provide information on how people react in situations of high moral intensity. Furthermore, decisions were measured using the self-judgment perspective (‘what would you do?’ and ‘How would you feel?’; Heinrichs et al., this issue) as indicators of participants’ intentions (aims, valence). However, in future research, it could be fruitful to use other methods to detect whether and to what extent participants experience ambivalence or internal conflict, and to what extent they feel committed to one method of action.

Moreover, participants were asked how they would act and feel in hypothetical situations presented as text-based stimuli. Thus, the decisions they made in this study do not necessarily correspond to the behaviour they would display in real life. Furthermore, there is a need to develop more realistic settings of data collection, allowing for a better understanding of decision-making, emotions, and actions. This might be possible, for example, in the field or with experimental studies. The results of the present investigation might also differ from those studies, if the participants were encouraged to reflect on their intentions as related to stimuli presented in an interview and embedded in interpersonal conversation, or to come up with their own narratives telling their experiences or motives in obeying or breaking moral rules in their everyday lives. Moreover, from the very beginning of HV research, the measurement procedure has been criticised for not really identifying emotions, but emotion attributions or emotion justifications. It would be important to develop sophisticated and valid measures of moral emotions in the context of patterns of moral decision-making (see Heinrichs et al., 2015; Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger & Latzko, this issue).

5.1.2 Limitations and Further Perspectives in Regard to Displaying the Process of Acting

Therefore, to reflect on the present study, the results call for further research to provide deeper insights into the process of intention formation and further sub-processes of moral actions. It would be interesting to know whether and to what extent individuals differ in subjectively constituted problems or in assessing the moral intensity of situations, depending on their individual moral principles or values, on self- and social sanctions, and on non-moral values and needs. MDS use and HV or UV patterns may emerge, at least in different forms, depending on whether ambivalence or internal conflict was perceived, or whether the individual managed to cope with his or her negative emotions (Bandura, 2016). To build commitment to one preferred way of acting (victimising or moral acting), the agent has to activate mechanisms of self-regulation based on social or self-sanctions (Bandura, 2016). Nevertheless, we must admit that the way of measuring intentions, emotions, or applied MDS regarding the given situations is far from validly displaying the sequence of inner sub-processes. In future research, specific experimental studies may offer, for example, data on forming an intention, attributing emotions, or justifying decisions under contrasting conditions.

5.1.3 Limitations and Further Perspectives From a Developmental Perspective

Furthermore, this paper mainly focused on the process of acting rather than on individual development. The present study only captures one measurement point and includes students representing emerging adults. To develop implications for moral education, it would be relevant to at least study the development of relevant personal determinants, such as MDS. Research on MDS has provided interesting results from a developmental perspective. Osofsky, Bandura, and Zimbardo (2005) indicated a low, but significant correlation between MDS and age. Older participants reported higher levels of MDS. However, a correlation between age and MDS only provides superficial indications and calls for a deeper understanding of underlying processes. In respect to this, Bandura offered a more sophisticated assumption, that the development of MDS is in line with a change of preference from social sanctions in childhood and earlier years to self-sanctions among adults (Bandura, 2016). This idea is quite consistent with the basic assumption in the Kohlbergian tradition of studying moral development. Kohlberg claims social sanctions to be important at the preconventional level. At the conventional level, not one person but a social group or system, may sanction deviant or immoral behaviour. At the postconventional level the agent is assumed to have developed into a person with autonomous judgement and a strong ‘moral self’, committed to a hierarchy of values, and able to reflect on moral problems from a perspective of legitimacy. Thus, the relevance of social sanctions seems to decrease; however, self-sanctions might increase on the way to higher moral stages. However, there is empirical evidence that such an individual-constructivist (vs. social-constructivist) idea of moral development towards an autonomous moral self ignores phenomena such as situational impact on moral judgements and patterns of HV (as well as HM, UM, HM) during adolescence and adulthood (Beck & Parche-Kawik, 2004; Heinrichs et al., 2015; Krebs & Denton, 2005).

The action-theoretical approach presented in this paper provides a perspective to explain HV as a pattern emerging within the action process, particularly regarding immoral behaviour among adults. People choose to jeopardise their own standards and seem to feel happy about a decision in favour of a moral transgression if they manage to find ways to cope with inner conflicts and get strongly committed towards their intention. This idea is in line with Bandura, who presented the concept of moral disengagement as an indicator of lacking self-regulation concerning cases of immoral behaviour. To conclude, the three approaches, the action-theoretical model, the HV pattern in adulthood as a pattern emerging during the process of acting, as well as the concept of moral disengagement, address the same basic question: how can people act in ways that contradict their moral principles, at least in some situations, without feeling distress or having a bad conscience? This study indicates that we have to acknowledge that breaking moral rules or standards is quite common, even among adults, at least as studied here in situations of lower moral intensity. Otherwise, findings have revealed that people do commit to fairness, sharing, and others’ well-being (Fehr & Fischbacher, 2004; Fehr & Schmidt, 1999, 2006).

However, the results presented are far from being valid for drawing evidence-based conclusions concerning moral education. Nevertheless, the approach reconstructs (happy or unhappy) victimising in an action-based perspective as a result of intention formation, and provides long-term perspectives for education that also differ from those discussed in this special issue on the HV pattern in adulthood and adolescence (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger & Latzko, this issue; Minnameier, this issue). To reduce MDS use or foster reflective use of strategies like MDS offers an approach that differs from common methods of moral education, such as supporting moral judgment competence with respect to cognitive development (Minnameier, 2012), fostering moral expertise (Narvaez & Lapsley, 2005), or developing moral emotions (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger & Latzko, this issue).

Additionally, from an educational perspective, the results of the present study only pointed to the empirical ‘is’ in decision-making, intentions, emotion attributions, and moral disengagement in morally relevant situations. There is an additional need to discuss aims considering also norms and values and legitimate curricula. It seems important to reflect on whether students should be encouraged to follow their moral ideals in certain situations, even if they must accept great (personal) disadvantages. Perhaps it would be preferable to enable them to balance their own needs and those of others. Minnameier would argue that sometimes, it is morally adequate to behave as a strategic moralist (Minnameier, this issue; Minnameier, Heinrichs & Kirschbaum, 2016). He states, for example, that to implement trustful cooperation in the long term, depending on the situational conditions, an individual may have to adopt his or her way of acting towards moral standards of partners or one’s environment. Sometimes it may be recommended to look for strategies (e.g., in cooperative games) that may lead to moral behaviours in a sense of an overarching moral aim, such as developing trustful cooperation and preventing others from pursuing only their own needs and getting rich at the expense of the individual in the long-term.

Overall, there are considerably contrasting positions concerning the aims of moral education. It is discussed controversially whether moral education should focus on struggling to promote autonomously judging moral agents and accept that some of them may end up as unhappy moralists (Oser & Reichenbach, 2005), or whether it would be better to foster individuals who are able to choose ways of acting that may lead to showing HV patterns when considering the situational conditions for implementing morality and acting as strategic moralists. However, there seems to be a common position underlying this discourse of ‘successfully engaging in meaningful, positive and caring relationships is both a prerequisite for and consequence of successful teaching and learning processes (Malti, Häcker, & Nakamura, 2009). Moreover, meaningful relationships are especially important in a globalised society […]‘ (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger & Heinrichs, this issue) to create a ‘moral atmosphere’ (Kohlberg, 1984), supporting moral actions and the development of socio-moral competencies.

HM = happy moralizing pattern; HV = happy victimizing pattern; MDS = moral disengagement strategies; UM = unhappy moralizing pattern; UV = unhappy victimizing pattern

1 The definition of problem used here mainly points to the individually constituted discrepancy between is and ought. In terms of problem-solving approaches (e.g. following Dörner, 1979), it includes tasks and problems (for a more sophisticated discussion, see Heinrichs, 2005).

Bandura, A. (1990). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in

terrorism. In Reich, W. (Ed.), Origins of terrorism:

Psychologies, ideologies, theologies, states of mind (pp.

161–191). Cambridge: Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise

of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education, 31(2),

101–119.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0305724022014322

Bandura, A. (2016). Moral Disengagement: How people do harm

and live with themselves. New York, NY: Worth Publishers.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli,

C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of

moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

71(2), 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364

Bandura, A., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Pastorelli, C.,

& Regalia, C. (2001). Sociocognitive self-regulatory

mechanisms governing transgressive behaviour. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 80(1),

125–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.1.125

Beck, K., & Parche-Kawik, K. (2004). Das Mäntelchen im Wind?

Zur Domänenspezifität moralischen Urteilens [The wave in the wind?

Towards domain specificity of moral judging]. Zeitschrift für

Pädagogik, 50(2), 244–265.

Boardley, I. D., & Kavussanu, M. (2007). Development and

validation of the moral disengagement in sport scale. Journal

of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 29(5), 608–628.

https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.29.5.608

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: qualitative,

quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Los

Angeles: Sage.

Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., & Sweitzer, V. L. (2008). Moral

disengagement in ethical decision-making: a study of antecedents

and outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2),

374–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.374

Döring, B. (2013). The development of moral identity and moral

motivation in childhood and adolescence. In K. Heinrichs, F.,

Oser, & T. Lovat (Eds.), Handbook of moral motivation.

Theories, models, applications (pp. 289–305). Rotterdam:

Sense Publishers.

Dörner, D. (1979). Problemlösen als

Informationsverarbeitungsprozess [Problem solving as

information processing]. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Spinrad, T. L. (2007).

Prosocial development. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, & R. M.

Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social,

emotional, and personality development (p. 646–718). John

Wiley & Sons Inc.

https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0311

Esser, H. (1996). Die Definition der Situation [Definition of the

Situation].Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und

Sozialpsychologie, 48(1), 1–34.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness,

competition, and cooperation. Quarterly Journal of Economics,

114(3), 817–868.

https://doi.org/10.1162/003355399556151

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. (2006). The economics of fairness,

reciprocity and altruism: Experimental evidence and new theories.

In: S.-C. Kolm, & J. M. Ythier (Eds.), Handbook of the

economics of giving, altruism and reciprocity (pp.

615–691). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2004). Third-party punishment and

social norms. Evolution and Human Behaviour, 25(2),

63–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-5138(04)00005-4

Fida, R., Paciello, M., Tramontano, C., Fontaine, R. G.,

Barbaranelli, C., & Farnese, M. L. (2015). An integrative

approach to understanding counterproductive work behaviour: The

roles of stressors, negative emotions, and moral disengagement. Journal

of Business Ethics, 130(1), 131–144.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2209-5

Gasser, L., Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E., Latzko, B., & Malti,

T. (2013). Moral emotion attributions and moral motivation. In K.

Heinrichs, F. Oser, & T. Lovat (Eds.), Handbook of moral

motivation. theories, models and applications (pp.

304–320). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Gollwitzer, P.M. (1996). Rubikonmodell der Handlungsphasen.

[Rubikon model of action phases] In J. Kuhl, & H. Heckhausen

(Eds.), Motivation, Volition und Handlung (pp. 531–582).

Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E., & Heinrichs, K. (2020). The happy

victimizer pattern in adulthood – state of the art and contrasting

approaches: Introduction to the special issue. Frontline

Learning Research, 8(5), 1-4.

https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v8i5.681

Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E., & Latzko, B. (2020). Happy

victimizing in emerging adulthood: reconstruction of a

developmental phenomenon? Frontline Learning Research, 8(5),

47-69. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v8i5.382

Haidt, J., & Craig J. (2008). The moral mind: How five sets of

innate intuitions guide the development of many culture-specific

virtues, and perhaps even modules. In P. Carruthers, S. Laurence,

& S.P. Stich (Eds.), The innate mind: Foundations and

the future, evolution and cognition (Vol. 3; pp.

367–391). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heckhausen, H., Gollwitzer, P.M., & Weinert, F. E. (1987). Jenseits

des Rubikon [Beyond the Rubicon]. Berlin:

Springer.

Heinrichs, K. (2005). Urteilen und Handeln – Ein

Prozessmodell und seine moralpsychologische Spezifizierung

. [A process model of judging and acting and its moral

psychological specification] (Vol. 12). Frankfurt a. M.:

Peter-Lang-Verlag.

Heinrichs, K. (2010). Urteilen und Handeln in der moralischen

Entwicklung [Judging and action in a developmental perspective].

In B. Latzko, & T. Malti (Eds.), Moralentwicklung und

Moralerziehung in Kindheit und Adoleszenz (S. 69–86).

Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Heinrichs, K. (2013). Moral motivation in the light of action

theory. In K. Heinrichs, F. Oser, & T. Lovat (Eds.),Handbook

of Moral Motivation. Theories, Models and

Applications (pp. 623–657). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Heinrichs, K., Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E., Latzko, B.,

Minnameier, G., & Döring, B. (2020). Happy Victimizing in

adolescence and adulthood – Empirical findings and further

perspectives, Frontline Learning Research, 8(5), 5-23.

https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v8i5.385

Heinrichs, K., Minnameier, G., Latzko, B., &

Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E. (2015). „Don’t worry, be happy“? – Das

Happy-Victimizer-Phänomen im berufs- und wirtschaftspädagogischen

Kontext [“Don’t worry, be happy”? – The happy victimizer

phenomenon in the context of vocational and business education]. Zeitschrift

für Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik, 111(1),

32–55.

Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision-making by individuals in

organisations: an issue contingent model. Academy of

Management Review, 16(2), 366–395.

https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1991.4278958

Keller, M., Lourenço, O., Malti, T., & Saalbach, H. (2003).

The multifaceted phenomenon of ‘happy victimizers’: a

cross‐cultural comparison of moral emotions. British Journal

of Developmental Psychology, 21(1), 1–18.

https://doi.org/10.1348/026151003321164582

Kohlberg, L. (1984). The psychology on moral development:

The nature and validity of moral stages (Vol. II). New

York: Harper & Row.

Krebs, D. L., & Denton, K. (2005). Toward a more pragmatic

approach to morality: a critical evaluation of Kohlberg's model. Psychological

Review, 112(3), 629–649. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.112.3.629

Krettenauer, T., Malti, T., & Sokol, B. (2008). The

development of moral emotions and the happy victimizer phenomenon:

a critical review of theory and applications. European

Journal of Developmental Science , 2, 221–235.

https://doi.org/ 10.3233/DEV-2008-2303

Lakatos, I. (1978). The Methodology of scientific research

programmes. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of

observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1),

159–174. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/2529310

Lapsley, D. K., & Narvaez, D. (2005). Moral psychology at the

crossroads. Character psychology and character education, In D. K.

Lapsley, & C. Power (Eds.), Character psychology and

character education (pp. 18–35). Notre Dame: University of

Notre Dame Press.

Latzko, B., & Malti, T. (2010). Children's moral emotions and

moral cognition: Towards an integrative perspective.New

Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 129, 1-10.

https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.272

Lind, G. (2019). Moral ist lehrbar!: Wie man

moralisch-demokratische Fähigkeiten fördern und damit Gewalt,

Betrug und Macht mindern kann [Morality can be taught!

How we can foster moral-democratic abilities and reduce violence,

fraud and power]. Berlin: Logos.

Malti, T., & Krettenauer, T. (2013). The relation of moral

emotion attributions to prosocial and antisocial behaviour: A

meta‐analysis. Child Development, 84, 397–412.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01851.x

Malti, T., Häcker, T., & Nakamura, Y. (2009). Sozial-emotionales

Lernen in der Schule [Socioemotional learning in schools].

Zurich: Pestalozzianum.

Malti, T., Averdijk, M., Zuffianò, A., Ribeaud, D., Betts, L. R.,

Rotenberg, K. J., & Eisner, M. P. (2016). Children’s trust and

the development of prosocial behavior. International Journal

of Behavioral Development, 40(3), 262–270.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415584628

Mayring, P. (2015). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen

und Techniken [Qualitative content analysis: Basics and

techniques]. Weinheim: Beltz.

McAlister, A. L., Bandura, A., & Owen, S. V. (2006).

Mechanisms of moral disengagement in support of military force:

The impact of Sept. 11. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology,

25(2), 141–165. h

ttps://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2006.25.2.141

Minnameier, G. (2020). Explaining Happy Victimizing in adulthood –

A cognitive and economic approach. Frontline Learning Research,

8(5),70 - 91.

https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v8i5.381

Minnameier, G. (2012). A cognitive approach to the ‘happy

victimizer’. Journal of Moral Education, 41(4),

491–508.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2012.700893

Minnameier, G., Heinrichs, K., & Kirschbaum, F. (2016).

Sozialkompetenz als Moralkompetenz – Wirklichkeit und Anspruch?

[Social competence as moral competence – reality and demand?]. Zeitschrift

für Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik, 112(4),

636–666.

Minnameier, G., & Schmidt, S. (2013). Situational moral

adjustment and the happy victimizer. European Journal of

Developmental Psychology , 10(2), 253–268.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2013.765797

Moore, C., Detert, J. R., Treviño, L., Baker, V. L., & Mayer,

D. M. (2012). Why employees do bad things: Moral disengagement and

unethical organisational behaviour. Personnel Psychology,

65(1), 1–48.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01237.x

Narvaez, D., & Lapsley, D. K. (2005). The psychological

foundations of everyday morality and moral expertise. In D. K.

Lapsley, & C. Power (Eds.), Character psychology and

character education (pp. 140–165). Notre Dame: University

of Notre Dame Press.

Neuweg, G. H. (1999). Könnerschaft und implizites Wissen -

Zur lehr-lerntheoretischen Bedeutung der Erkenntnis- und

Wissenstheorie Michael Polanyis [Expertise and tacit

knowledge – the relevance of Michael Polanyi’s theory of knowledge

for teaching and learning]. Münster: Waxmann.

Nunner-Winkler, G. (2013). Moral motivation and the happy

victimizer phenomenon. In: K. Heinrichs, F. Oser, & T. Lovat

(Eds.), Handbook of moral motivation. Theories, models,

applications (pp. 267–287). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Nunner-Winkler, G. (2007). Development of moral motivation from

childhood to early adulthood. Journal of Moral Education,

36(4), 399–414.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240701687970

Nunner-Winkler, G. (1993). Die Entwicklung moralischer Motivation

[The development of moral motivation]. In W. Edelstein, G.

Nunner-Winkler, & G. Noam, G. (Eds.), Moral und Person

(pp. 278–303). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Nunner-Winkler, G., & Sodian, B. (1988). Children's

understanding of moral emotions. Child Development, 59,

1323–1338. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130495

Oser, F. K., & Reichenbach, R. (2005). Moral resilience – The

unhappy moralist. In W. Edelstein, & G. Nunner-Winkler (Eds.),

Morality in context, advances in psychology (pp.

203–224). North Holland: Elsevier.

Osofsky, M. J., Bandura, A., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2005). The

role of moral disengagement in the execution process. Law and

Human Behaviour, 29(4), 371–393.

https://doi.org/10.2307/1130495

Rothmund, T., & Baumert, A. (2014). Shame on me - implicit

assessment of negative moral self-evaluation in shame-proneness. Social

Psychological and Personality Science, 5(2),

195–202.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550613488950

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice.

Los Angeles: Sage.

Sokolowski, K. (1993). Emotion und Volition [ Emotion

and Volition]. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Sokolowski K. (1996). Wille und Bewusstheit [Will and

consciousness]. In: J. Kuhl, & H. Heckhausen (Eds.),

Enzyklopädie der Psychologie: Themenbereich C Theorie und

Forschung, Serie IV Motivation und Emotion, Band 4 Motivation,

Volition und Handlung (pp. 485–530). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Thoma, S. J., & Bebeau, M. J. (2013). Moral motivation and the

four component model. In K. Heinrichs, F. Oser, & T. Lovat

(Eds.), Handbook of moral motivation. theories, models and

applications (pp. 49–67). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Tirri, K. (1999). Teachers' perceptions of moral dilemmas at

school. Journal of Moral Education, 28(1),

31–47.

https://doi.org/10.1080/030572499103296

Weinberger, A. & Frewein, K. (2019). VaKE (Values and

Knowledge Education) als Methode zur Integration von Werterziehung

im Fachunterricht in heterogenen Klassen beruflicher Schulen:

Förderung von kognitiven und affektiven Zielen [VaKE (Values and

Knowledge Eduation): A measure for integrating values education in

domain specific lessons in heterogeneous classes in vocational

schools: Fostering cognitive and affective goals]. In K. Heinrichs

& H. Reinke (Eds), Heterogenität in der beruflichen

Bildung. Im Spannungsfeld von Erziehung, Förderung und

Fachausbildung (S. 181–194). Reihe Wirtschaft – Beruf –

Ethik. Bielefeld: wbv.

Hypothetical situations for the assessment of moral decision-making

[Introduction for the participants] The following section shows various descriptions of situations. We would like to ask you to read through these situations carefully and to imagine yourself in the described situations. There are always exactly two alternative actions. Please decide in favour of one of them by marking the appropriate alternative with a cross. Afterwards, you will be asked to give reasons for your decision. Please indicate the main reasons in any case. In the end, you will be asked how you would have felt by acting as stated in each case.

Situation 1—Travel Costs

Please imagine the following situation:

You are working for a large international company and attend a national meeting within the framework of your employment company. Accidentally, a friend hast to go to the same city as you do. He offers to give you a ride. You accept his offer willingly. During the return journey, you have a nice chat. Nobody from your company knows or has noticed that you didn’t take your own car, and therefore have no expenses of your own. The travel expenses for this journey would be 50 euros. The formula for the travel expenses report says that only real travel costs are refundable. The friend can settle up his travel expenses himself, so that you don’t have to refund him anything.

Please put yourself into this situation and decide what you would

do:

( ) You claim the travel expenses of 50 euros.

( ) You don’t claim the travel expenses of 50 euros.

Please give reasons for your decision… [these statements from participants are the basis for coding the mechanisms of MDS]

How would you feel if you would had really acted like that?

Please mark only one possible answer.

( ) very good ( ) rather good ( ) rather bad ( ) very bad

Situation 2—Change

Please imagine the following situation:

Due to the fact that you speak Spanish very well, you go on holiday in Spain. You have earned the money for your holiday by working in a factory. During a day trip by bus to a distant city, you buy a handmade wooden sculpture for your parents in a craft shop. It is 50 euros. You pay with a 200 euro bill, and leave the shop. As you count your change outside the shop, you notice that the seller has given you back four 50 euro bills instead of 150 euros, inadvertently.

Please put yourself in this situation and decide what you would

do:

( ) You return 50 euros to the seller.

( ) You keep the 50 euros.

Please give reasons for your decision… [these statements from participants are the basis for coding the mechanisms of MDS]

How would you feel if you would had really acted like that?

Please mark only one possible answer.

( ) very good ( ) rather good ( ) rather bad ( ) very bad