VOL. 4, No. 1

This research targeted the learning preferences, goals and motivations, achievements, challenges, and possibilities for life change of self-directed online learners enrolled in a massive open online course (MOOC) related to online teaching hosted by Blackboard using CourseSites. Data collection included a 40-item survey, of which 159 MOOC respondents completed the close-ended survey items and 49 completed the 15 open-ended survey items. Across the data, it is clear that self-directed online learners are internally motivated and appreciate the freedom to learn and the choice that open educational resources provide. People were also motivated to learn informally from personal curiosity and interest as well as professional growth needs and goals for self-improvement. Identity as a learner was positively impacted by informal online learning pursuits. Foreign language skills as well as global, cultural, historical, environmental, and health-related information were among the most desired by the survey respondents. The main obstacles to informal online learning were time, costs associated with technology use, difficulty of use, and lack of quality. Qualitative results, embedded in the findings, indicate that self-directed learners take great pleasure in knowing that they do not have to rely on others for their learning needs. Implications for instructional designers are offered.

We are in the midst of an incredible array of changes in both K-12 and higher education today that would have been unthinkable just a decade or two ago. As part of the proliferation of global online education, people in remote parts of the world are learning from well-known professors at institutions such as Princeton, Rice, Harvard, and MIT; typically, without a fee (Friedman, 2013; Pappano, 2012; Sandeen, 2013). Countless millions of individuals are engaged in self-directed, informal, and solitary learning experiences, while myriad others are collaboratively learning with global peers who have signed up for the same course or learning experience (Kim, 2015). With the emergence of Web-based learning resources and tools, global collaboration and self-directed learning are now parallel and simultaneous events (Lee & Bonk, 2013). In the process, new ecologies of learning are emerging that need to be better understood (Kim & Chung, 2015; Wilcox, Sharma, & Lippel, 2016).

Waks (2013) in his book, Education 2.0: The learningweb revolution and the transformation of the school, offers a conceptual model to make sense of the educational possibilities brought about by an age of abundance of learning technologies. He points out that collaborative technologies, open access textbooks, e-books, learning repositories, social networking technology, Web conferencing, and open educational resources (OER) are enabling greater opportunities for learners’ self-determined or self-directed learning. Detailed below are a few key trends and historical markers for this self-directed learning movement or shift toward the use of more free and open content.

The evolution of OER and OpenCourseWare (OCW) (MIT, 2001), and online learning in general, has led to the creation of massive open online courses (MOOCs). MOOCs illustrate the fact that we have entered an age of information abundance in huge contrast to previous times of information scarcity (Kop, Fournier, & Mak, 2011). Taking advantage of such resources, thousands, or even tens or hundreds of thousands of people around the world often enroll in a single MOOC experience such as ones on social networking technology, sustainable health diets, introductory chemistry, or artificial intelligence (Bowman, 2012). While it is a recent phenomenon, by early 2016, more than 4,000 such courses across a wide range of disciplines were available from MOOC providers such as Udemy, Udacity, Coursera, NovoEd, and edX and listed in portals such as Class Central and the MOOC list (Bersin, 2016; Online Course Report, 2016; Wexler, 2015). Equally impressive, over 35 million learners enrolled in such courses that were offered by instructors from more than 570 different universities (Carter, 2016; Online Course Report, 2016; Shah, 2015). By the end of 2016, this grew to more than 58 million students enrolled in nearly 7,000 MOOCs at over 700 universities around the world (Shah, 2016). Coursera alone accounted for more than 23 million MOOC enrollments.

Research from Rita Kop and her colleagues (Kop et al., 2011) indicated that it is possible for a MOOC to provide more than traditional course information and assignments. MOOCs, in fact, can support the building of connections between those seeking to learn something and course facilitators as well as among the learners themselves in a rich online community. When designed to harness information flows within networks of people, the result can be exciting and spontaneous learning. Such MOOCs illustrate concepts and principles related to a new learning perspective called connectivism (Downes, 2012) and have been branded as “cMOOCs” (Morrison, 2013). In fact, the first MOOC, which was offered by George Siemens of Athabasca University and Stephen Downes of the Canadian Research Council in 2008 (Downes, 2012), was a cMOOC.

It was not until three years later that MOOCs received national and international attention. More specifically, in the Fall of 2011, a series of MOOCs from Stanford each enrolled more than 100,000 participants (Beckett, 2011; Markoff, 2011). These were dubbed xMOOCs since they were taught in a similar fashion to campus-based lecture courses (Morrison, 2013). Due to the size of the enrollments, MOOCs have drawn much media and government attention (Young, 2012). Naturally, there is much interest and attention today related to the business plans and sustainability of these new forms of educational delivery (Bonk, Lee, Reeves, & Reynolds, 2015, 2018; Kolowich, 2013) as well as their impact on the educationally underserved (Bethke, 2016; Schmid, Manturuk, Simpkins, Goldwasser, & Whitfield, 2015). In addition, MOOC experts and educators are debating issues related to accreditation, assessment, attrition, design and development, quality, personalization, competency, and credentialing (Bonk et al., 2018; Lee & Reynolds, 2015).

Among the other key concerns related to MOOCs and the use of open education include participant motivation and retention as well as resulting learning (Lee & Reynolds, 2015). A MOOC study in the area of bioelectricity at Duke University highlighted the fact that many people attend the first couple of weeks of a MOOC and then are no longer heard from (Belanger & Thornton, 2013; Catropa, 2013); a large percentage, in fact, sign up but never access any of the course resources or engage in any of the course activities. Similarly, a set of six MOOCs at the University of Edinburgh (e.g., courses on critical thinking, introductory philosophy, equine nutrition, AI planning, astrobiology, e-learning and digital cultures) also found that the retention rate in a MOOC is often quite low (MOOCs @ Edinburgh, 2013). In terms of participant motivation and goals in the Edinburgh study, participants signed up for various reasons, including the desire to learn about the subject matter, try online education, experience a MOOC, browse the course, obtain a certificate, improve career prospects, and become part of a learning community.

Recent studies of MOOCs and other forms of open education have relied on both data analytics and clickstream forms of data which can be problematic (Christensen, Steinmetz, Alcorn, Bennett, & Woods, 2013; edX, 2014). Clearly, while MOOCs may enroll thousands of participants who view a particular online lecture or respond to a set of survey questions, scant information is provided about why a certain lecture or a particular survey answer was selected more often. Additional insights can be garnered from expanding the data collected beyond computer log data (Gasevic, Kovanovic, Joksimovic, & Siemens, 2014).

In one of the largest qualitative studies of MOOCs, Veletsianos and his colleagues (Veletsianos, Collier, & Schneider, 2015) have uncovered many insights related to MOOCs and open education. Importantly, they remind us of the saliency of learner choice and personal agency when deciding to sign up for a MOOC or browse open educational resources (OER). To them, learner interviews, focus groups, content analyses, and other qualitative research methods often better illuminate learner aspects of self-directed online learning (Lee, 2016). These methods can be especially important for learners who tend to be more shy or quiet in the MOOC (Veletsianos, 2015). Without a doubt, it is vital to begin to understand the emotions, study skills, learning goals, actual achievements, challenges and potential frustrations, and social networks of those learners. In effect, enhanced insights into the people engaged in learning from MOOCs and other forms of open education are needed (Lee, 2016; Liu et al, 2014; Watson et al., 2015; Weibe, Thompson, & Behrend, 2015).

Without a doubt, informal learning resources and tools are proliferating online (Bonk, 2009; Cross, 2007). As a consequence of this age of information abundance, there is greater emphasis on self-directed learning and learners assuming more control over their learning activities (Brookfield, 2013; Sze-Yeng & Hussian 2010); especially in online environments (Song & Hill, 2007). This trend is pervasive across all age levels and occupations. For instance, some young people are skipping K-12 school settings and instead studying from OER (Al Haddad, 2011). Other youth who lack decent textbooks or have limited access to quality teachers, such as young children in India, are learning from free and open videos provided by the Khan Academy (Chandrasekaran, 2012). At the same time, some adolescents are learning multiple languages through free online video and text resources (Leland, 2012).

The importance of self-directed learning (SDL) has been noted for decades. Research from Deci and Ryan at the University of Rochester (e.g., Deci & Ryan, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2000), for instance, reveals the need for learning tasks to be personally meaningful, interesting, enjoyable, and embedded with a sense of control or personal autonomy. Learners must also be given a chance to set personal goals and self-monitor their progress toward them (Reeve, 1996). In recapping the literature on SDL, Abdullah (2001) noted that those who are self-directed learners are persistent, self-disciplined, goal oriented, independent, self-confident, and generally enjoy learning. They also self-monitor, evaluate, and regulate their own learning.

From this perspective, learners need greater opportunities to learn, and, in the process, gain a sense that they are free to learn when and where they feel the need (Reeve, 1996). Learning should be learner-driven and filled with opportunities for learners to make decisions and take responsibility for their own learning (Rogers, 1983). The more that learners can freely and openly explore learning experiences, the greater the chance that they will exhibit their creativity and participate in productive ways in the world at large (Rogers, 1969). In effect, there is a growing need for allowing greater learner choice and fostering volition in the material that is selected and in the tasks in which they express their learning gains. Learner volition and inner will or purposeful striving toward some action or learning goal is at the crux or heart of self-directed learning pursuits. In recapping the literature on intrinsic motivation, Pink (2009) makes the claim that this internal drive system is focused on getting better at something that is personally meaningful or relevant.

In many ways, distance learning on the Web is an ideal platform for testing theories related to intrinsic and self-directed learning (SDL). For many of the pioneers of distance learning research, learning via television, correspondence, and satellite were highly appropriate formats for learners who were already self-motivated (Wedemeyer, 1981). Building on decades of such learning formats, Garrison (1997) designed a comprehensive SDL model with three interacting dimensions; namely, (1) self-management, (2) self-monitoring, and (3) motivation. Garrison pointed out that SDL is successful when learners can take control of the learning context to reach their personal learning objectives (Song & Hill, 2007). To attain to their goals, they must effectively manage the learning resources that are provided; often with little or no guidance. Of course, as learning online from OCW, OER, and MOOCs shifts control of the learning environment toward the learner, there are problems, challenges, and opportunities for learners related to effective resource use. The challenges and barriers of many SDL environments include less immediate feedback and guidance, a high degree of impersonalization, learner procrastination, and being overwhelmed by the resources made available by the instructors or learning designers (Graham, 2006).

Given these issues, it is not too surprising that the recent emergence of online learning and OER has reawakened interest in the field of self-directed learning (Hyland & Kranzow, 2011). Adults, in particular, are being pressured to keep their knowledge and skills up-to-date in order to handle fast changing work requirements. As a result, lifelong learning and self-directed learning have risen in importance (Lin, 2008). However, there are relatively few studies of the experiences of self-directed online learners as they move through non-formal learning channels. Therefore, it is vital for researchers to investigate the potential of free and open learning materials and resources and what learners encounter as they explore them. In particular, there is a pressing need to better understand the goals and aspirations as well as the obstacles and barriers to success in non-formal learning environments by the people learning from open educational content and courses such as MOOCs or open learning portals.

As noted in the preceding section, free and open online learning resources have become widely available. One consequence of this more open educational world is that learners are increasingly self-directing major aspects of their learning. The purpose of this study, therefore, is to investigate the self-directed online learning pursuits of participants of a MOOC hosted by CourseSites from Blackboard.

More specifically, the research attempted to reveal the (1) learning preferences; (2) goals and motivations; (3) achievements; (4) obstacles and challenges; and (5) possibilities for life change of self-directed online learners. In similarity to studies from Liu et al. (2014) and Watson et al. (2015) which inquired into the preferences of learners in a MOOC, both qualitative and quantitative methods were employed in this study. However, unlike those studies, this particular project did not target MOOC behaviors specifically; instead, a survey was designed to explore self-directed learning preferences and experiences from informal online learning resources including MOOCs and other forms of open education. In effect, this research project attempted to more generally understand learner preferences, goals, successes, and challenges when engaged in informal online learning.

As educators and instructional designers better understand success stories as well as the challenges and obstacles of non-formal learning with OER and emerging learning technology, they can design and develop enhanced online learning contents and supports. In addition, documented life changes from OER can also serve as catalysts and benchmarks for others to utilize such resources (Bonk, Lee, Kou, Xu, & Sheu, 2015).

Web-Based Survey Instrument

A list of over 300 informal, open education, and extreme learning websites was created by a team of researchers based on a thorough literature review as well as from soliciting expert recommendations, reviewing online news, and scanning through blog posts and other online resources. These Web resources included those related to language learning, adventure learning, social change/global education, virtual education, learning portals, and shared online video. After six months of reviewing the literature and these recommendations, an evaluation scheme was developed for online informal learning resources. The final eight criteria in the scheme included: (1) content richness, (2) functionality of technology, (3) extent of technology integration, (4) novelty of technology, (5) uniqueness of learning environment/learning, (6) potential for learning, (7) potential for life-changing impact, and (8) scalability of audience. Each informal learning website was evaluated according to these eight criteria using a 5-point Likert scale (1 is low; 5 is high) (Bonk, Kim, & Xu, 2016; Kim, Jung, Altuwaijri, Wang, & Bonk, 2014).

After spending a year evaluating 305 of these websites (Bonk, et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2014), a 40-item survey questionnaire was designed using SurveyShare, a Web-based survey hosting service. As indicated, the survey was designed to better understand the preferences, goals, achievements, and obstacles of self-directed learning from such free and open online environments. It was also intended to help the researchers collect personally impactful stories related to self-directed learning (Bonk, Lee, Kou, et al., 2015; Bonk et al., 2016). The close-ended portion of the survey inquired into many aspects of informal online learning (e.g., favorite websites when needing information, goals one wished to accomplish through informal learning pursuits, reasons for exploring Web resources informally, and typical barriers or obstacles faced when learning informally on the Web. In effect, these questions addressed a wide gamut of issues related to informal and self-directed learner use of open educational resources and open learning opportunities.

In addition to those 25 close-ended questions, respondents had the option to complete 15 open-ended questions that asked about their informal learning experiences (See Appendix A for details on the “Open-Ended Survey Questions”). Among them were questions related to respondent goals and aspirations using OER, OCW, and MOOCs. Participants were also asked about their most interesting and successful informal learning experiences and what they accomplished. Another open-ended item concerned advice or suggestions for others wanting to learn informally with OER, OCW, and other Web resources and technologies. Still other open-ended items included those related to the informal learning influences and supports that they received (e.g., colleagues, mentors, friends, etc.). Finally, we were curious about the challenges and obstacles that informal learners faced when using online educational resources.

Analysis of the Qualitative Data

The qualitative data from relevant open-ended questions was analyzed by a team of qualitative researchers. Team members coded the data for themes and comparisons across such themes. Where appropriate, the qualitative findings were used in the sections below to supplement the quantitative findings from the close-ended items already discussed.

Analyses of the qualitative data evolved over time with repeated checks from the research team members. After several rounds of preliminary analyses and discussions, it was decided to examine the responses to all 15 open-ended items for each survey participant. Essentially, participant answers to the 15 questions were treated as one short interview for each respondent. This decision was important since respondent goals, motivations, achievements, and challenges related to OER, OCW, and MOOCs might actually be embedded in an adjacent question to the one that specifically asked about it. Two rounds of coding were required to generate the requisite coding scheme. The qualitative data analysis is intended to make evident how human lives are impacted from self-directed online learning using open forms of education.

Background on the Data and the Subject Population

A massive open online course (MOOC) on Instructional Ideas and Technology Tools for Online Success was taught from late April to early June in 2012. It was hosted by the e-learning company, Blackboard, using their free course management system called CourseSites. Shortly after the course ended, a link to the 40-item Web-based survey was sent out to 3,800 participants of the MOOC. The survey took approximately 15 to 20 minutes to complete. As a mixed methods study, various quantitative results are supplemented by our open-ended survey findings.

There were 159 completed surveys from the Blackboard MOOC participants, including 49 who completed the optional open-ended items. The majority of the survey respondents were female (73%) and were from North America (81%). In addition, 72% were over 40 years old. It is important to mention that a large percentage of the respondents in this subject pool were college instructors who signed up for the MOOC as a means of enhancing their skills in teaching online. They found out about the MOOC through press releases from Blackboard as well as from an email message sent to users of CourseSites.

Respondents were asked about the places in which they learned informally with technology as well as the devices that they used for such endeavors. Not too surprisingly, the MOOC respondents typically used a laptop computer (89%) or desktop computer (75%) to access informal learning resources. The majority of respondents also used a smart phone (67%) or tablet computer (52%). At the same time, many of these individuals relied on devices such as e-book readers (39%), iPods (28%), car CD/DVDs (26%), or TV with Internet (15%) to informally learn with technology. Clearly, while traditional desktop and laptop computing devices are the most common informal learning access points, there are a wide range of delivery mechanisms for engaging in informal and open learning today. As noted, most respondents also utilized smart phones as well as tablet computers and nearly half had some type of an e-book reader. Such mobile learning devices extend the possibilities for self-directed informal learning to all aspects of one’s life and all types of activities in which one engages.

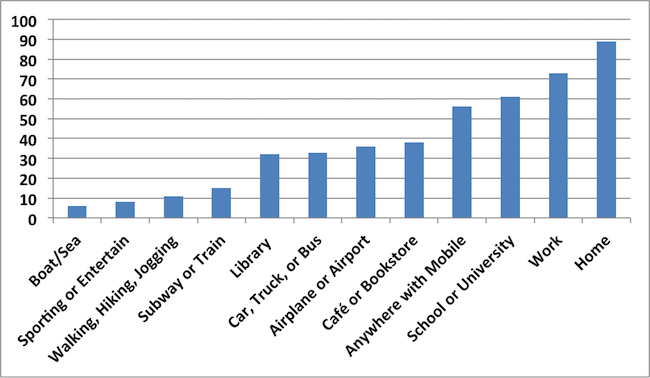

It was also deemed important to know where people are typically located when using such devices. Home (89%), work (73%), school or university (61%), or anywhere with a mobile device (56%) were among the popular places for accessing informal learning resources and materials (see Figure 1). Other common locations included a café or bookstore (38%), car, truck, or bus (33%), library (32%), and subway or train (15%). Respondents were also engaged in such activities when hiking, walking, or jogging (11%), attending sporting or entertainment events (8%), and when on a boat or out at sea (6%). As the earlier question about delivery vehicles for informal learning indicated, it seems that learning is occurring in all aspects of one’s life. Stated another way, mobile computing devices and wireless connections to the Internet are vital aspects of learning today; especially that which is informal, open, and in more extended or unusual situations, such as when on an excursion or engaged in a leisure pursuit.

While understanding the devices and locations for informal learning is informative, it is also vital to know what Web resources self-directed learners are accessing to learn. To address this issue, we inserted two general survey questions about such resources. First, we asked the respondents to list the three best web sites, other than search engines, that they used for learning something when they had a fairly simple task or question. Somewhat predictably, most of the respondents listed Wikipedia and YouTube as resources that they used to address such basic knowledge question needs. The next most popular resources for factual information were Lynda.com, Facebook, Ask.com, eHow, and WebMD. In addition, four people mentioned Pinterest, TED, Twitter, or online dictionaries in general. And three people listed How Stuff Works, the Khan Academy, Lifehacker, The New York Times, TechRepublic, Wolfram Alpha, or Yahoo Answers. Evidently, if people cannot find an answer in Wikipedia or YouTube, the possible avenues one might pursue to get an answer can multiply.

Figure 1. Places respondents engage in informal learning with technology (N = 158).

Next, we inquired about the three best educational or information-rich websites that users might recommend to others to significantly change their lives in a positive way. The top “life-changing” resource listed was TED talks, followed by YouTube and Wikipedia. Tied for fourth on the list were iTunes University and the Khan Academy. After that, resources deemed life changing included MERLOT, the BBC, EDUCAUSE, Free Technology for Teachers, Lifehacker, and the MIT OCW project. A few people mentioned the Chronicle of Higher Education, the New York Times, and Pinterest.

The respondents were also asked how they find out about new or interesting informal resources on the Web to learn from. More than 75% simply browsed the Web on their own. The next most important information sources were email, e-newsletters, and online news or announcements. After that, respondents relied on their friends and colleagues or blogs or podcasts to which they subscribed. Social networking sites like Facebook, Twitter, and Google Hangouts were also popular. Evidently, learners no longer solely turn to printed news, books, and magazines or even instructors for their learning. Such information sources remain important but were far down the list of the preferred options.

In addition to the tools and resources for self-directed learning, we hoped that this research would shed insight into the purposes and goals of those attempting to learn informally with technology. According to the survey results, the vast majority of our respondents simply wanted to acquire a new skill or competency (85%). At the same time, many hoped to learn something that they could use to help others (65%) or society in general (37%). Nearly half of the respondents indicated that they desired to acquire cultural knowledge (45%), teamwork or collaboration skills (44%), or something to better their lives (44%). Four in ten respondents explored resources on the Web in order to learn how to fix something. Somewhat fewer were there to engage in a game or learning quest (21%). Ironically, only one-third were learning informally in hopes of course credit and even fewer were interested in completing courses or modules that did not count for a degree (27%). What is clear is that respondents learn informally online with specific skills in mind, not the eventual completion of a course or degree program. Humanitarian and personal reasons typically outweigh academic ones.

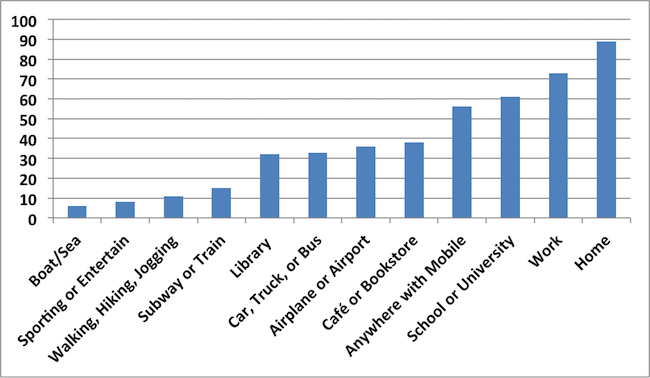

Respondents were then asked about specific information or knowledge in which they would like to learn informally online. As shown in Figure 2, roughly half were seeking language skills or cultural information. Nearly 4 in 10 respondents often were hoping to gain health-related content or global information. Also important was historical information (36%), environmental information (27%), science skills (25%), vocabulary (23%), artistic skills (23%), and mathematical skills (19%). Interestingly, far fewer were intending to gain outdoors, musical, or athletic skills.

Figure 2. Specific information or knowledge wanting to learn informally online (N = 154)

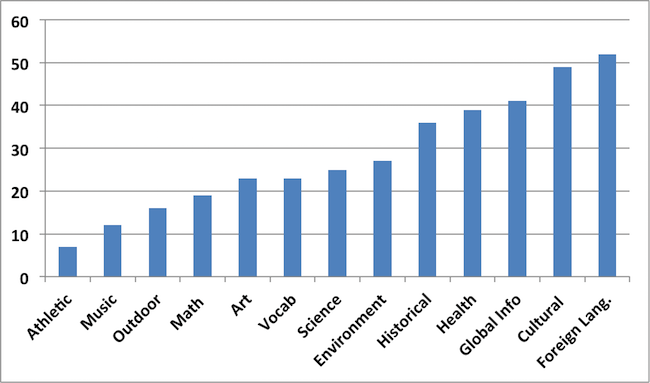

As shown in Figure 3, there are many intrinsically motivating factors involved in informal learning online. Survey respondents found their general interest in the topic to be vital (see Figure 3). Most also selected professional growth needs, curiosity, a personal need for information, goals for self-improvement, and choice or freedom in the selection of topics or resources to explore as the main reasons for accessing informal online learning resources and websites. Other motivational factors included wanting to learn something new, feelings of personal control over one’s own learning, and finding that a website or activity looks exciting. Somewhat surprisingly, only about one in five respondents indicated that they explored the Web as part of their hobbies.

When asked about the purposes or goals from their most interesting informal online learning activity, there were many motivators. In building on our quantitative findings detailed in Figure 3, our qualitative analyses of the open-ended survey items also explored learner motivation. Overall, the key findings about learner motivation hold from both of these analyses, though to different degrees, with more emphasis on one’s hobbies and informal learning quests in the open-ended items. Among our primary qualitative findings were five key motivators or goals for the respondents; namely, they wanted: (1) to improve their job prospects; (2) to pursue personal interests or hobbies; (3) to obtain certification of some type; (4) to access particular information or resources; and (5) to find ways to expand upon their formal learning. While these goals were quite diverse, each relates to finding a way to improve one’s competencies or life situation.

Figure 3. Main reasons to informally explore the Web to learn (N = 158)

Suffice to say, the reasons for self-directed online learning are quite varied, from basic information seeking to expanding upon one’s career knowledge base to job advancement to personal fulfillment. In terms of information seeking, many participants see the Web as a means of self-reliance. As one respondent noted, she and her husband were DIYers. “Today, we were trying to install a pool filter—we got instructions off You Tube. I also just bought a recumbent exercise bike—I looked at online reviews before making a choice.” She then added, “Knowing that I did not need to ask an actual person for help was life changing. I am an introvert by nature, and I prefer to figure things on my own. Knowing that I can research informally on the Web is reassuring.”

As shown by the above quote, several traits or characteristics about informal online learners emerged from the data. As alluded to above, many felt a strong degree of intrinsic motivation and prided themselves for being a self-directed learner. As part of this, they emphasized the aspect of informal learning that was most valuable; namely, “my own pleasure” or passion. Such individuals valued their learning autonomy and considered it highly empowering. As one person stated, “I continue to research my interests for my own pleasure, especially on sites like Amazon for books and e-books, and have ongoing email alerts for journal content. I also use online sources for job hunting and professional networking.” Simply put, self-directed online learning is a highly gratifying and rewarding experience.

This sense of personal gratification, at least in part, comes from the fact that many of one’s information needs are readily accessible online. As an earlier quote indicated, the fact that a person no longer has to rely on someone else for assistance is extremely reassuring to self-directed online learners. In effect, informal learning from OER seems to increase self-confidence and enhances one’s sense of self-efficacy as a learner.

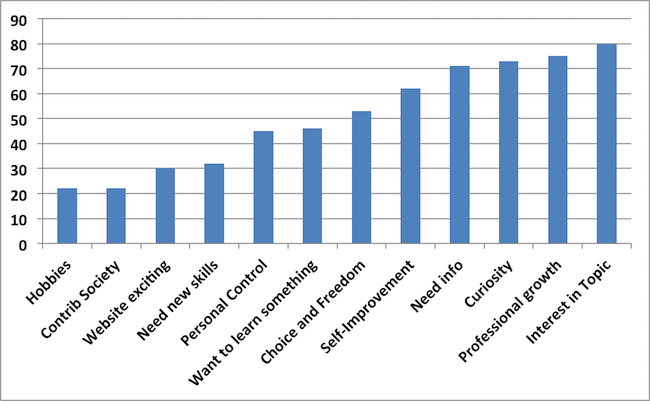

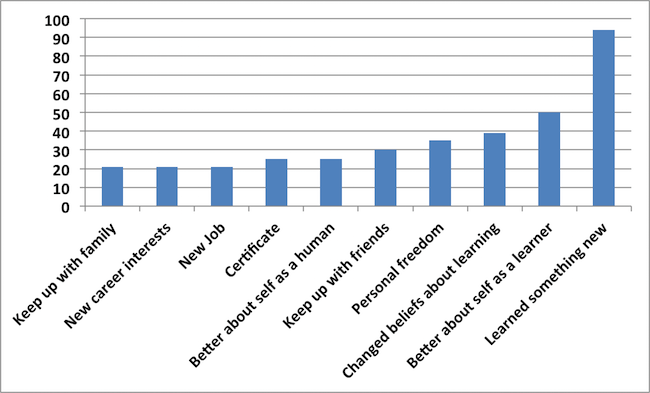

It was deemed important to ask what people typically accomplished when in informal online environments. Fortunately, as displayed in Figure 4, most respondents realized their goal of learning something new (84%). Half of them felt better about themselves as learners. Many even changed their beliefs about what learning is (39%). A sense of personal freedom was noted by 35% of the respondents. Around 30% deemed keeping up with their friends to be a major achievement, while 20% said the same about keeping up with family members. Importantly, slightly more than one in five got a new job from their informal learning experiences. A similar percentage discovered a new occupational or career interest, while slightly less of the respondents (16%) were promoted in their work setting. In addition, one in four had received a certificate of some type. Based on such responses, there is no doubt that informal online learning is changing the lives of many people.

As indicated by in the earlier quote about installing a pool filter, there is also increased confidence and pride when one can be self-directed in learning. Similarly, another respondent noted, “I don't know if you consider this formal or informal but it has been something I have accomplished on my own. It has been empowering and rewarding to become a research detective online.” Clearly, this individual valued the enhanced learning independence and sense of personal accomplishment from utilizing open education content and resources.

Figure 4. Achievements from learning informally online (N = 156)

Not too surprisingly, when these Blackboard MOOC participants were asked about their most interesting or successful informal learning experience, many of them focused on their recent MOOC experience. Others discussed prior professional development experiences (e.g., learning a new screencasting software tool, finding resources for stories of indigenous populations in Australia for one’s class, etc.). Some detailed their hobbies and personal interests (e.g., learning the Korean language from podcast shows while bike riding, finding an interesting new recipe, locating information for sightseeing during a conference in New Orleans, watching TED talks on climate change or neuroscience, etc.). Others mentioned additional online courses or MOOCs that they had taken or were in the midst of. As is evident, our findings do not relate strictly to MOOCs; nonetheless, responses related to the Blackboard MOOC that they had all just experienced clearly filtered through many of their open-ended responses.

Implicit within the Figure 4 data is the notion that many respondents mentioned increased their sense of personal identity from their informal learning pursuits, and, as a result, they felt better about themselves as a learner. The following quote from a female respondent is quite telling.

It has made my job much easier and it's been easier for me to execute certain tasks, making me more willing to take on bigger challenges. It was also shown me how enjoyable it is to learn a computer language. It opened my mind to considering possibilities in this area. It also made my husband respect my ability around computers a bit more.

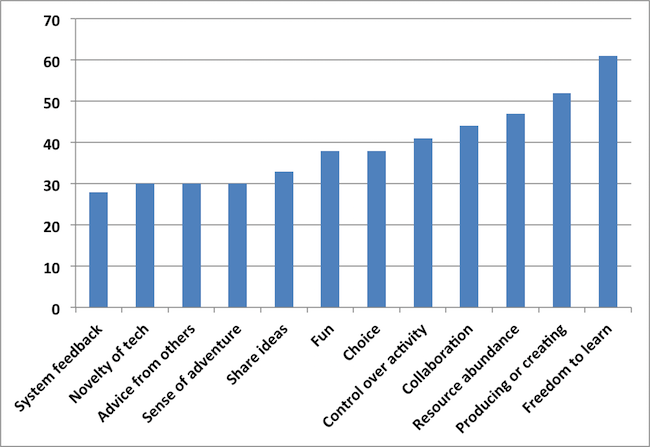

Experiencing high levels of achievement or success in informal online learning is vital, but it is also important to understand the factors that lead to those successes and failures. Figure 5 provides an overview of some of the key ones. As would have been predicted by Rogers (1969), freedom to learn was rated the highest (61%), followed by having an opportunity to create or produce something (52%), a sense of resource abundance (47%), collaboration (44%), control over the activity or resource (41%), choice (38%), and a sense of fun (38%). Opportunities to share ideas, feel some sense of adventure, receive advice from others, experience a novel technology, and obtain system feedback were also important. What these results signal is that informal learners want the freedom to choose what they want to learn. When the resource pool increases, so, too, do the choices and opportunities for learner autonomy.

Figure 5. Factors leading to success or personal change when learning informally online (N = 159)

The qualitative data also indicated that another important characteristic of these self-directed learning respondents was that they enjoyed meeting people with similar interests in an online community; however, they would not necessarily enjoy face-to-face (FTF) interaction with these same people. There apparently is some psychological safety from realizing that the expert resources are available online when needed but that you do not have to personally meet or know the individuals who are helping you out.

In addition, our analyses indicated that a fairly common trait of these informal learners was that they considered sharing to be an important part of the educational process. Informal learners often become part of a network of peers who “love the nuggets of information that I share with them” (e.g., podcast information, recent technology news, etc.). As one person noted, informal learning “influenced my professional life – I guess I have more social capital.” Another stated:

My key moment came when I discovered a community of like-minded scholars from around the world. I no longer felt isolated or disconnected. This has become my most valuable support network and I am grateful.

Another trait revealed in the qualitative data was their personal pride in creating or contributing something to the MOOC or informal learning resources that others could use. Such feelings of pride and personal empowerment make sense since, as noted in the earlier literature review, self-directed learning often leads to exploration and creative outcomes (Lin, 2008; Waks, 2013). However, it is a balancing act. As one person argued, when credentials like badges are added, they tend to take away from the fun and enjoyment of learning something new. Such extrinsic motivators often turn a playful pursuit of learning into a competition.

Just play around with ideas for alternatives to printed texts and don't be afraid to create your own, even if they're amateurish. Perhaps people who are experimenting can get together in groups: as writers, [sic] people (including me) don't seek out readers enough and that will also apply to people experimenting with alternative modes. I think we need to de-emphasize [sic] formal assessment and accreditation and encourage our playful side to see what is possible. Too much informal learning wants to get itself 'badged' or validated too quickly and this means it’s losing its genuine amateur status.

At the same time, another respondent who successfully completed two workshops offered by Wiki Educator and learned many new skills about wikis found herself, “highly motivated to do all I could and learn as much as possible.” This respondent also stated that the “certification scheme in the wiki workshop was also very motivating, and I achieved Wiki Apprentice 2 level so far.”

Finally, any achievement from self-directed learning often requires some form of support or guidance. Consequently, one survey question inquired as to the supports for their informal learning on the Web. More than 60% of the survey respondents sought help from friends and colleagues, whereas 20% relied on their teachers or instructors. Relatively few relied on counselors or advisors (3%), family members (11%), or tutors or mentors (11%). Instead of family members or tutors, nearly one-third utilized experts and one-fourth trusted upon people that they never met. In effect, many respondents felt comfortable seeking out external experts or people that they did not personally know. Given the power of the Web to connect individuals across time and distance, this may be one of the key findings of this study.

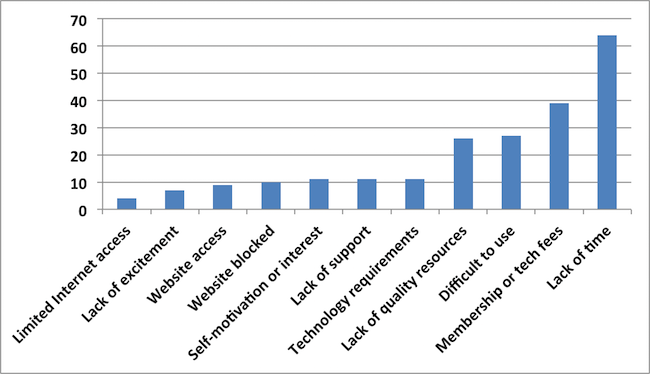

We were not only interested in informal learning successes, but also obstacles and challenges that respondents faced in their self-directed learning pursuits. Of the four key problems or challenges salient in Figure 6, the most significant, not unexpectedly, was the lack of time for informal online learning (64%). Another obstacle was the fact that some informal learning resources and tools have associated technology or membership fees (39%). And if they are free, they may be difficult to use (27%). Fourth, for many people, high quality informal learning resources are simply difficult to locate (26%). Less significant issues or challenges related to technology requirements embedded in the use of informal learning resources, support issues, website accessibility, and self-motivation or interest to use.

Figure 6. Obstacles and challenges faced when learning informally online (N = 158)

Several participants mentioned the issue of trust when discussing their informal and self-directed learning problems. As one person stated, “the only challenge is knowing if a website is a trusted one.” Another mentioned, “Don't be too trusting of the documentation. It's written by humans and has the potential for error. Move on, don't waste time.” In effect, the participants were raising issues about quality. Another raised the issue of finding quality content, “I think the hardest part is finding a MOOC that would work. It is not like there is a directory of MOOCs.” To be fair, as noted earlier, many such MOOC directories have emerged since that time (e.g., Class Central, the MOOC List, etc.). In addition to discerning the availability and quality of open educational content and resources, some of our respondents mentioned that informal learning was not taken seriously by their superiors. This situation, too, will likely improve over time.

When these individuals who attended the MOOC were asked to rate the impact of informal Web-based experiences on their lives, the vast majority were highly positive. In fact, on a scale of 0 (i.e., “No Impact”) to 5 (“Some Positive Impact”) to 10 (“Significant Positive Impact”), only 5% of the respondents indicated a rating of under 5 and 8% were neutral. Even more impressively, 1 in 5 respondents marked 10 and nearly 80% indicated a 7 or higher in terms of impact. Apparently, informal learning leaves an indelible mark on one’s life.

There is a dearth of knowledge about the motivations, achievements, and challenges of self-directed online learners. As mentioned in the literature review, this particular study follows the lead of Veletsianos et al. (2015), Liu et al. (2015), and Watson et al. (2015) in offering qualitative insights into learner activity when engaged in MOOCs and other forms of open education. As a mixed methods study, the survey not only revealed general insights into the learning habits, needs, and goals of, and obstacles to, self-directed online learners but also more specific insights into the actual learning needs and experiences of those utilizing such environments. Given this scope, we contend that the findings of the present study address many audiences including higher education administrators, policy makers, learners, instructors, instructional designers, digital scholars, and researchers. As such stakeholders might hope, the present research indicates that open educational courses and content have directly benefited many people who long for the freedom and opportunity to direct their own learning pursuits.

This research project investigated five key areas of the self-directed and informal learning pursuits of people enrolled in a MOOC; namely, their: (1) learning preferences; (2) goals and motivations; (3) achievements; (4) obstacles and challenges; and (5) opportunities for life change. A summary of the findings related to each area is offered below.

Learning in the 21st century takes place in many arenas. Informal learning not only occurs in the home, school, and work environments, but also in a wide array of other potential learning environments, such as cafés, libraries, trains, and airports. Nevertheless, home, work, and school environments still predominate. And, as displayed by recent developments in tablet computing and smart phones, the use of devices to access these assorted informal contents is expanding. When online, our survey participants were often supported not just by friends and colleagues, but also by leading experts that they have never met.

OER plays a key role in the lives of self-directed learners. As shown in a parallel study of ours (Bonk, Lee, Kou, et al., 2015), respondents often turned to Wikipedia and YouTube for their initial online inquiry. However, unlike our previous study, other useful online resources include Lynda.com, Twitter, Facebook, TED talks, and online dictionaries. Many of the sites preferred by the respondents to this particular study might be considered online portals and referenceware such as The New York Times, WebMD, Ask.com, and Yahoo Answers. Not too surprisingly, several of the other key resources mentioned were shared online video sites (e.g., TED, How Stuff Works, the Khan Academy, etc.). Clearly, social media, email, e-newsletters, and online news sites help in providing awareness to newly popular informal learning resources as they emerge. Perhaps among the most noteworthy finding of this study, and for readers of the Journal of Learning for Development (JL4D), was that many of these resources were deemed to hold potential for significant life change (e.g., the BBC, iTunes University, the Chronicle of Higher Education, the MIT OCW project, and MERLOT) (see also Kim, et al., 2014).

There are myriad goals and motivations for informal online learning. In similarity to a previous study of ours (Bonk, Lee, Kou, et al., 2015), among the primary incentives include professional growth, self-improvement, learning about a specific topic, satisfying one’s curiosity, and general information needs. Informal online learners, including MOOC and open education participants, appreciate the options and opportunities to learn on their own. The personal freedom to explore whatever one wishes to learn is a key reason why self-directed online learning is so powerful. Many of the respondents had specific goals that were highly personal in nature. Others wanted to learn something that would help others or society as a whole.

As people explore informal online resources, they enhance their professional expertise, acquire the skills to fix things at home, school, or work, become more confident in themselves as learners, and find ways to help others in need of similar knowledge. Evidently, such intrinsic motivators pervade informal learning endeavors, thereby allowing the various walls previously inhibiting learning to be readily pushed aside.

Across the data, there is enhanced understanding of the goals of self-directed online learners across different open education delivery systems including OCW, OER, and MOOCs. Better documentation of these pursuits can motivate and inspire others. It can also help designers of such environments to better understand the goals of self-directed online learners, thereby enabling them to create more engaging informal learning experiences, resources, and environments. At the same time, this enhanced understanding might lead to ideas on how to support individuals who lack such self-directed learning skills.

In terms of actual achievement, our initial findings are quite revealing. Among the achievements found in the qualitative as well as quantitative data was simply feeling better about oneself as a learner. There is an enhanced sense of identity and self-worth. Some of the open-ended responses revealed people who were discovering areas of interest to be passionate about. And others were beginning to recognize their new skills and talents.

Many people who decide to learn online from OER or MOOCs are perpetual learners. Such learners include individuals who are looking to move up in their careers as well as others simply wanting to learn something new about a topic of interest. These self-directed online learners are acquiring skills in starting up new businesses, Web design, computer science, teaching, speaking a language, and many other fields. They are gaining these skills through videos, discussions, documents, and a host of online resources. Along the way, they are learning how to fix bicycles and swimming pools, practice a new language, discover vast new communities of like-minded scholars, become online researchers and detectives, and improve their current and future job prospects. They are also creating and sharing personal creations or works of art, finding and sharing novel resources, and experiencing a new sense of freedom to learn. It is vital to add that most of them seem to be having much fun while in the midst of such informal learning quests. Clearly, the open learning world has provided exciting ways for these individuals to learn informally online and they are quickly taking advantage of it.

Despite these positive findings, many important challenges and issues remain. For instance, time, quality, training, technology requirements, and cost remain barriers to full participation in such Web resources, courses, and opportunities. Internet access and firewall issues, though lower than expected, still hold back too many learners from pursuing their passions or finding new ones. Perhaps the challenge that can be most readily addressed by educators and instructional designers is providing help in finding and evaluating the quality of open educational content. Fortunately, researchers are increasingly targeting this issue with frameworks and various quality assurance criteria for assessing the quality of online contents (Margaryan, Bianco, & Littlejohn, 2015; Mishra & Kanwar, 2015; Swan, Day, Bogle, & van Prooyen, 2015). Better understanding of the barriers and obstacles when learning from OER or a MOOC should prove highly valuable to the designers of such content as well as those creating new online education courses and degree programs from that content.

One of the final areas of interest was whether the participants experienced some type of life change from their use of informal learning resources. Importantly, nearly 9 in 10 respondents indicated that they had, in fact, experienced a life change from their informal learning pursuits. Given that similar results were also found in a parallel study of ours (Bonk, Lee, Kou, et al., 2015), such overwhelming results clearly signal that self-directed online learning pursuits are having a major societal impact; especially that which is more informal and outside the purview of traditional forms of education.

Lives are being changed, both modestly (e.g., obtaining a specific skill to use that same day) or in more monumental ways (e.g., getting a new job or moving up at work). For many, open educational resources, massive courses, and other online content offer a sense of accomplishment outside of the high stress of most formal educational arenas. In informal Web-based settings, there is a chance for discovery, reflection, choice in one’s learning path, and much opportunity for greater self-confidence and enhanced personal identity.

In addition to the open issues that remain, there were several key limitations that should be mentioned related to this particular study. First of all, the survey respondents were participants in a MOOC addressing online instruction tools and techniques. It is likely that such people have more experience using online resources and open content than the average person. On a related issue, there is an underlying assumption that most MOOC participants are self-directed online learners. Despite such assumptions, we admittedly did not examine the self-directed learning traits of the research participants. That remains an open issue for future researchers.

In terms of respondent demographics, the MOOC participants were predominantly female and most were over age 40. Geographically, the vast majority were from North America. Further narrowing the generalizability, most were employed as instructors in higher education settings. As readers of this journal realize, people in rural communities in southern Tanzania, western China, or the outback of Australia might have vastly different motivations and expectations from using open educational content as well as highly distinctive challenges, systems of support, and actual achievements. One should also keep in mind that these MOOC participants volunteered or self-selected for the study. It is likely that such individuals had more positive open education experiences to share. Had all 3,800 people enrolled in the MOOC responded to the survey, many of the aggregate results presented here might have been different. Clearly, the response rate of 4% was particularly low, but such response rates are not uncommon for opt-in online surveys (Cho & LaRose, 1999).

There were still other limitations. For instance, only 49 of the 159 survey respondents answered the open-ended items. In addition, due to the self-paced nature of the course, we do not know how many people successfully completed the MOOC. At last count, just a couple dozen people received badges for course completion. Finally, as a mixed methods study, only a portion of the qualitative results could be included here due to length limitations.

Despite the above limitations, there are numerous instructional design implications from this study. First of all, those designing open educational contents such as MOOCs, OCW, or OER for self-directed learners need to embed opportunities for learner choice, control, fun, professional growth, and a general sense of freedom to learn. Often, such learners are not pursuing course credits, credentials, or items on their transcripts; instead, they simply want specific topical information that can help them deal with a personal issue or problem at work. As such, instructional designers need to make access to that information expedient and convenient while also fostering additional learner curiosity and exploration. Clearly, better understanding of the key learning motivators by those designing the instruction would appear to be crucial in enhancing and extending the learning outcomes.

Second, implicit in our research findings is that technology selection does matter to self-directed online learners. Given their interest in personal and professional growth, instructional designers might embed opportunities for discussion and reflection with others using online discussion forums, synchronous chats, collaboration tools, and learning communities. Such tools can foster a sense of external support and caring for one’s self-directed learning pursuits. Self-directed learners not only want to learn from others, they also want access to productivity tools that allow them to offer something creative or generative in return. However, technology cost issues and ease of use continue to play a central role in ultimate use.

Third, the designers and developers of Web resources for informal and self-directed learning need to realize that with the plethora of resources to select from, there is a need for guidance in finding, selecting, and using high quality content. For instance, MOOCs have evolved so quickly that, as mentioned, there are now lists of MOOC options (e.g., Class Central, TechnoDuet, the MOOC List, and Open Culture). Of course, all MOOC vendors (e.g., edX, Coursera, Udacity, Canvas, NovoEd, etc.) have their lists as well. In addition to such MOOC listings, various models and frameworks for self-directed distance learning, such as those from Garrison (1997) and Song and Hill (2007), can offer insights into the learning processes and opportunities for such learners. Admittedly, however, these MOOC-related frameworks, tools, and resources will need to relentlessly evolve to keep pace with the vast and perpetual human learning and development changes taking place in this age of increasingly free and open education (Bonk, 2009, 2015; Kop & Fournier, 2010).

This was just one study of the vast field of MOOCs and open education. However, a parallel study of MIT OCW users by Bonk, Lee, Kou, et al. (2015) confirms many of the findings detailed here. Additional inroads are now needed. For instance, it is vital to understand the specific types of resources that informal learners find valuable for their changing learning needs. What are the purposes and goals that lead someone to use a specific OER over another or to sign up for a particular MOOC? And what factors or learning components support participant retention in a MOOC? Are there online supports or scaffolds that can be embedded to directly address the paltry completion numbers of most MOOCs to date (Catropa, 2013; Sandeen, 2013)?

Given the findings of the current study, there are many directions for such research. First, direct interviews with participants should reveal specific motivational factors in accessing and using open educational contents. Do these motivational tendencies lean toward intrinsic aspects of motivation or more extrinsic ones? Inquiries into the benefits of informal learning pursuits should also be investigated. Do informal learners hope to receive some type of credential or badge from the completion of a MOOC or pass a test related to their OCW explorations? It is plausible that additional insights into the key motivators can lead to immediate application, thereby benefiting countless learners around the planet.

These are among the questions that our research team is currently exploring. We are not alone. As an emerging field of study, there will be waves of research questions that appear during the coming decade. Given that self-directed learning from informal online contents is fast becoming a key aspect of one’s learning history, every person could be impacted in some way from such research. As a result, we hope to play a small role in the evolution of this widening field of self-directed online learning from open educational contents. At the same time, we look forward to the discoveries of other researchers and scholars who are simultaneously pushing the field of MOOCs and open education ahead in their own unique and exciting ways, including those who publish their ground-breaking and illuminative works here in the JL4D.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge Sarah-Bishop Root and Jarl Jonas of CourseSites by Blackboard for their timely, extensive, and unwavering support in this research project. They warmly encouraged the first author to offer the first massive open online course (MOOC) sponsored by Blackboard. In addition, Shuya Xu from Indiana University (IU) is thanked for the design of the survey instrument used in this study. Many other members of the Self-directed Online Learning Environments (SOLE) research team at IU offered their support to this project and are thanked here.

Abdullah, M. H. (2001, December). Self-directed learning, Eric Digest, EDO-CS-01-10. Available from: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED459458.pdf

Al Haddad, A. (2011, November 11). Too smart for school, too young for college. The National. Available from: http://www.thenational.ae/news/uae-news/too-smart-for-school-too-young-for-college

Beckett, J. (2011, August 16). Free computer science courses, new teaching technology reinvent online education. The Stanford Report. Available from: http://news.stanford.edu/news/2011/august/online-computer-science-081611.html

Belanger, Y., & Thornton, J. (2013, February 5). Bioelectricity: A quantitative approach. Duke University's first MOOC. Available from: http://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/10161/6216/Duke_Bioelectricity_MOOC_Fall2012.pdf

Bersin, J. (2016, January, 5). Use of MOOCs and online education exploding and here’s why. Forbes. Available from: http://www.forbes.com/sites/joshbersin/2016/01/05/use-of-moocs-and-online-education-is-exploding-heres-why/#b4c28997f090

Bethke, R. (2016, May 2). Developing country MOOC users not like those the U.S. eCampus News. Available from: http://www.ecampusnews.com/top-news/developing-country-mooc/

Bonk, C. J. (July 2009). The world is open: How Web technology is revolutionizing education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Bonk, C. J., Kim, M., & Xu, S. (2016). Do you have a SOLE?: Research on informal and self-directed online learning environments. In J. M. Spector, B. B. Lockee, & M. D. Childress (Eds.), Learning, design, and technology: An international compendium of theory, research, practice and policy. Section: Informal resources and tools for self-directed online learning environments (pp. 1-32). AECT-Springer Major Reference Work (MRW).

Bonk, C. J., Lee, M. M., Kou, X., Xu, S. & Sheu, F.-R. (2015). Understanding the self-directed online learning preferences, goals, achievements, and challenges of MIT OpenCourseWare subscribers. Educational Technology and Society, 18(2), 349-368. Available from: http://www.ifets.info/journals/18_2/26.pdf;

Bonk, C. J., Lee, M. M., Reeves, T. C., & Reynolds, T. H. (Eds). (2015). MOOCs and open education around the world. NY: Routledge.

Bonk, C. J., Lee. M. M., Reeves, T. C., & Reynolds, T. H. (2018). The emergence and design of massive open online courses. In R. A. Reiser & J. V. Dempsey (Eds.), Trends and issues in instructional design and technology (4th Ed.), (pp. 250-258). New York, NY: Pearson Education.

Bowman, K. D. (2012, Summer). Winds of change: Is higher education experiencing a shift in delivery?, Public Purpose Magazine (from the American Association of State Colleges and Universities). Available from: http://www.aascu.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=5570

Brookfield, S. D. (2013). Powerful techniques for teaching adults. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Carter, J. (2016). MOOC and learn: The university with 35 million students. TechRadar. Available from: http://www.techradar.com/us/news/world-of-tech/mooc-and-learn-the-university-with-35-million-students-1318037

Catropa, D. (2013, February 24). Big (MOOC) data. Inside Higher Education. Available from: http://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/stratedgy/big-mooc-data

Chandrasekaran, A. (2012, October 15). Lacking teachers and textbooks, India’s schools turn to the Khan Academy to survive. The New York Times Blog. Available from: http://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/10/15/lacking-teachers-and-textbooks-indias-schools-turn-to-khan-academy-to-survive/

Christensen, G., Steinmetz, A., Alcorn, B., Bennett, A., & Woods, D. (2013, November 6). The MOOC phenomenon: Who takes massive open online courses and why? University of Pennsylvania. Available from: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2350964

Cho, H., & LaRose, R. (1999). Privacy issues and Internet surveys. Social Science Computer Review, 17(4), 421-434.

Cross, J. (2007). Informal learning: Rediscovering the natural pathways that inspire innovation and performance. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer/Wiley.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Canadian Psychology, 49, 14-23. Available from: https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/SDT/documents/2008_DeciRyan_CanPsy_Eng.pdf

Downes, S. (2012, May). Connectivism and connected knowledge: Essays on meaning and learning networks. Available from: http://www.downes.ca/files/Connective_Knowledge-19May2012.pdf

edX (2014, January 21). Harvard and MIT release working papers on open online courses. edX Blog. Available from: https://www.edx.org/blog/harvard-mit-release-working-papers-open#.VOEnbo1TFjs

Friedman, T. (2013, January 26). Revolution hits the universities. The New York Times. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/27/opinion/sunday/friedman-revolution-hits-the-universities.html?_r=0

Garrison, D. R. (1997). Self-directed learning: Toward a comprehensive model. Adult Education Quarterly, 48(1), 18-33.

Gasevic, D., Kovanovic, V., Joksimovic, S., & Siemens, G. (2014). Where is research on massive open online courses headed? A data analysis of the MOOC Research Initiative. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 15(5). Available from: http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/viewFile/1954/3111

Graham, C. R. (2006). Blended learning systems: Definition, current trends, future directions. In C. J. Bonk and C. R. Graham (Ed.), The handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs (pp. 3-21). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer Publishing. Available from: http://www.publicationshare.com/c1-Charles-Graham-BYU--Definitions-of-Blended.pdf

Hyland, N., & Kranzow, J. (2012). Faculty and student views of using digital tools to enhance self-directed learning and critical thinking. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 8(2), 11-27. Available from: http://sdlglobal.com/IJSDL/IJSDL8.2.pdf

Kim, M., Jung, E., Altuwaijri, A., Wang, Y., & Bonk, C. J. (2014, Spring). Analyzing the human learning and development potential of websites available for informal learning. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 11(1), 12-28. Available from: http://sdlglobal.com/IJSDL/IJSDL%2011.1%20final.pdf

Kim, B. (2015). (Ed.). MOOCs and educational challenges around Asia and Europe. Seoul, Korea: KNOU Press.

Kim, P., & Chung, C. (2015). Creating a temporary spontaneous mini-ecosystem through a MOOC. In C. J. Bonk, M. M. Lee, T. C. Reeves, & T. H. Reynolds (Eds.), MOOCs and open education around the world (pp. 157-168). New York, NY: Routledge.

Kolowich, S. (2013, February 21). How EdX plans to earn, and share, revenue from its free online courses. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Available from: http://chronicle.com/article/How-EdX-Plans-to-Earn-and/137433/

Kop, R., & Fournier, H. (2010). New dimensions to self-directed learning in an open networked learning environment. International Journal of Self-Directed Learning, 7(2), 2-20. Available from: http://www.sdlglobal.com/IJSDL/IJSDL7.2-2010.pdf

Kop, R., Fournier, H., & Mak, J. S. F. (2011, November). A pedagogy of abundance or a pedagogy to support human beings? Participant support on massive open online courses. International Review of Research on Open and Distance Learning, 12(7). Available from: http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1041/2025

Lee, M. M. (2016). Exploring research paradigms for MOOCs and open education. Invited presentation at E-Learn 2016—World Conference on E-Learning, Washington, DC.

Lee, M. M., & Bonk, C. J. (2013). Through the words of experts: Cases of expanded classrooms using conferencing technology. Language Facts and Perspectives, 31,107-137.

Lee, M. M., & Reynolds, T. H. (2015). MOOCs and open education: The unique symposium that led to this special issue. In Special Issue: MOOCs and Open Education. International Journal on E-Learning, 14(3), 279-288.

Leland, J. (2012, March 9). Adventures of the teenage polyglot. The New York Times. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/11/nyregion/a-teenage-master-of-languages-finds-online-fellowship.html?pagewanted=all

Lin, L. (2008). An online learning model to facilitate learners’ rights to education. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(1), 127-143. Available from: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ837473.pdf

Liu, M., Kang, J., Cao, M., Lim, M., Ko, Y., Myers, R., & Weiss, A. S. (2014). Understanding MOOCs as an emerging online learning tool: Perspectives from the students. The American Journal of Distance Education, 28(3), 147-159.

Margaryan, A., Bianco, M., & Littlejohn, A. (2015). Instructional quality of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). Computers & Education, 80, 77-83.

Markoff, J. (2011, August 15). Virtual and artificial, but 58,000 want a course. The New York Times. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/16/science/16stanford.html?_r=0

Mishra, S., & Kunwar, A. (2015). Quality assurance for open educational resources: What’s the difference? In C. J. Bonk, M. M. Lee, T. C. Reeves, & T. H. Reynolds (Eds.), MOOCs and open education around the world (pp. 119-129). New York, NY: Routledge.

MIT (2001, April 4). MIT to make nearly all course materials available free on the World Wide Web. MIT News. Available from: http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2001/ocw.html

MOOC @ Edinburgh 2013 – Report #1 (2013). MOOC @ Edinburgh 2013 – Report #1. University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland. Available from: http://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/1842/6683/1/Edinburgh%20MOOCs%20Report%202013%20%231.pdf

Morrison, D. (2013, April 22). The ultimate student guide to xMOOCs and CMOOCs. MOOC News and Reviews. Available from: http://moocnewsandreviews.com/ultimate-guide-to-xmoocs-and-cmoocso/

Online Course Report (2016, January). State of the MOOC 2016: A year of massive landscape change for massive open online courses. Available from: http://www.onlinecoursereport.com/state-of-the-mooc-2016-a-year-of-massive-landscape-change-for-massive-open-online-courses/

Pappano, L. (2012, November 2). The year of the MOOC. The New York Times. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/04/education/edlife/massive-open-online-courses-are-multiplying-at-a-rapid-pace.html?pagewanted=all

Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. New York: Riverhead Books.

Reeve, J. (1996). Motivating others: Nurturing inner motivational resources. Allyn and Bacon: Boston.

Rogers, C. R. (1969). Freedom to learn: A view of what education might become. Columbus, OH: Charles Merrill.

Rogers, C. R. (1983). Freedom to learn for the 80s. Columbus, OH: Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68-78. Available from: https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/SDT/documents/2000_RyanDeci_SDT.pdf

Sandeen, C. (2013, Summer). Assessment’s place in the new MOOC world. Research & Practice in Assessment, 8, 5-12.

Schmid, L., Manturuk, K., Simpkins, I., Goldwasser, M., & Whitfield, K. E. (2015). Fulfilling the promise: Do MOOCs reach the educational underserved? Educational Media International. 52(2), 116-128. DOI: 10.1080/09523987.2015.1053288

Shah, D. (2015, December 21). By the numbers: MOOCs in 2015. Class Central. Available from: https://www.class-central.com/report/moocs-2015-stats/

Shah, D. (2016, December 25). By the numbers: MOOCs in 2016. Class Central. Available from: https://www.class-central.com/report/mooc-stats-2016/

Song, L., & Hill, J. (2007). A conceptual model for understanding self-directed learning in online environments. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 6(1), 27-42. Available from: http://www.ncolr.org/jiol/issues/pdf/6.1.3.pdf

Swan, K., Day, S., Bogle, L., & van Prooyen, T. (2015). AMP: A tool for characterizing the pedagogical approaches of MOOCs. In C. J. Bonk, M. M. Lee, T. C. Reeves, & T. H. Reynolds (Eds.), MOOCs and open education around the world (pp. 105-118). New York, NY: Routledge.

Sze-Yeng, F., & Hussian, R. (2010). Self-directed learning in a socioconstructivist learning environment. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 1913-1917.

Veletsianos, G. (2015, May 27). The invisible learners taking MOOCs. Inside Higher Ed. Available from: https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/higher-ed-beta/invisible-learners-taking-moocs

Veletsianos, G., Collier, A., & Schneider, E. (2015). Digging deeper into learners’ experience in MOOCs: Participation in social networks outside of MOOCs, notetaking and contexts surrounding content consumption. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(3), 570-587.

Waks, L. J. (2013). Education 2.0: The LearningWeb revolution and the transformation of the school. Builder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Watson, S. L., Loizzo, J., Watson. W. R., Mueller, C., Lim, J., & Ertmer, P. A. (2015). Instructional design and facilitation of a human trafficking MOOC: A case study of attitudinal change. Unpublished manuscript.

Wedemeyer, C. A. (1981). Learning at the back door: Reflections on nontraditional learning in the lifespan. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. Reissued: September 2010.

Weibe, E., Thompson, I., & Behrend, T. (2015). MOOCs from the viewpoint of the learner: A response to Perna et al. (2014). Educational Researcher, 44(4), 252-254.

Wexler, E. (2015, October 19). MOOCs are still rising, at least in numbers. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Available from: http://chronicle.com/blogs/wiredcampus/moocs-are-still-rising-at-least-in-numbers/57527

Wilcox, K. E., Sarma, S., & Lippel, P. H. (2016, April). Online education: A Catalyst for higher education reforms. MIT Online Education Policy Initiative: Final Report. Cambridge, MA: MIT. Available from: https://oepi.mit.edu/files/2016/09/MIT-Online-Education-Policy-Initiative-April-2016.pdf

Young, J. R. (2012, June 25). A conversation with Bill Gates about the future of higher education. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Available from: http://chronicle.com/article/A-Conversation-With-Bill-Gates/132591/

(28) Some people learn a lot from exploring Web resources or information on their own. Can you describe your most interesting or successful informal learning experience? What did you accomplish? Please provide as many details of your story as you can remember.

(29) In what ways was this informal learning activity unusual, interesting, or different compared to how you have learned in the past or compared to others?

(30) Why did you want to do this learning activity or task? What was your purpose or goals? Please describe what captured your interest.

(31) Has your life changed in a small or big way as a result of this informal learning activity or experience? If so, how?

(32) What was the key moment when learning informally with technology where you felt a personal change? If so, please describe that moment, as best you can. For instance, were there certain things you recall happening that led to this key moment?

(33) Did any of this influence your personal, school, or social life? If so, how or in what ways?

(34) Did you face any obstacles or challenges during this time when learning informally with technology? If so, how did you overcome them?

(35) What did you think about during this event or experience? Did you share your thoughts about this informal learning activity with anyone else? Please explain.

(36) Who or what influenced you to learn informally online or use a certain technology or online resource? Did you have any role models or mentors? Did anyone help you? If so, how?

(37) Did others help or support you to learn this way? For example, were there any friends, family members, or organizations that might have helped you?

(38) What role did technology play (if any) in this key moment? Stated another way, how did technology help your informal learning experience?

(39) Were there any cool, extremely different, or unusual uses of technology that helped you learn or succeed?

(40) Were there any particular technologies that you wish you had that might have helped improve your overall experience?

(41) Imagine someone trying to accomplish the same thing 10 years in the future. Can you think of what technologies or other supports they might use to accomplish a similar task? What technologies might you use in the future?

(42) How might others try to do what you are doing? Do you have any suggestions for others who want to learn on their own or informally with Web technology or resources?

Authors

Dr. Curtis J. Bonk is Professor at Indiana University teaching psychology and technology courses. Drawing on his background as a corporate controller, CPA, educational psychologist, and instructional technologist, Bonk offers unique insights into the intersection of business, education, psychology, and technology in his popular blog, TravelinEdMan. In addition to many national and statewide innovative distance teaching awards, in 2014, he received the Mildred B. and Charles A. Wedemeyer Award for Outstanding Practitioner in Distance Education, and, in 2016, he received the AACE Fellowship Award from the Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education for his leadership and service to the field. From 2012 to 2017, Bonk has been annually named by Education Next and listed in Education Week among the top contributors to the public debate about education from more than 20,000 university-based academics. He has authored several widely used technology books, including The World Is Open, Empowering Online Learning, The Handbook of Blended Learning, Electronic Collaborators, Adding Some TEC-VARIETY which is free as an eBook (http://tec-variety.com/), and, most recently, MOOCs and Open Education Around the World (http://www.moocsbook.com/). Email: cjbonk@indiana.edu

Dr. Mimi Miyoung Lee is Professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Houston (UH). She received her Ph.D. in Instructional Systems Technology from Indiana University at Bloomington in 2004. She is co-director of the UH doctoral program in curriculum and instruction focusing on urban education. During past few years, Mimi has published research on STEM related professional development programs, cross-cultural training research, interactive videoconferencing, self-directed learning from MOOCs and OpenCourseWare (OCW), and emerging learning technologies such as wikis. Her other research and teaching interests include global and multicultural education, woman leaders in Asia, teacher training for diversity, discourse analysis and CMC, and critical ethnography. Most recently, Professor Lee was co-editor of “MOOCs and Open Education Around the World” published by Routledge in 2015 as well as special journal issue of the International Journal on E-Learning (IJEL) on MOOCs and Open Education also in 2015. Email: mlee7@uh.edu