Research Article

Teens’ Vision of an Ideal Library

Space: Insights from a Small Rural Public Library in the United States

Xiaofeng Li

Assistant Professor

Department of Library and Information

Science

Pennsylvania Western

University

Clarion, Pennsylvania,

United States of America

Email: xli@pennwest.edu

YooJin Ha

Professor

Department of Library and

Information Science

Pennsylvania Western

University

Clarion, Pennsylvania,

United States of America

Email: yha@pennwest.edu

Simon Aristeguieta

Assistant Professor

Department of Library and Information

Science

Pennsylvania Western

University

Clarion, Pennsylvania,

United States of America

Email: saristeguiet@pennwest.edu

Received: 31 July 2023 Accepted: 10 Oct. 2023

![]() 2023 Li, Ha, and Aristeguieta. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2023 Li, Ha, and Aristeguieta. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30410

Abstract

Objective – This study

delves into the perspectives of teenagers regarding their desired teen space

within a small rural public library in the United States.

Methods – To capture

the richness of their thoughts, a visual data collection method was employed,

wherein 27 8th-grade participants engaged in a drawing activity during an art

class at a local middle school. Two additional teens were recruited for

individual semi-structured interviews.

Results – Through this

creative exercise, the study unveiled the various library activities,

amenities, books, and visual designs that resonated with the teens, as they

envisioned their ideal teen space.

Conclusion – The study’s

findings hold practical implications for librarians working with this

population, offering valuable insights to enhance and optimize teen services at

the library. By aligning the library’s offerings with the desires of the young

patrons, the potential for a thriving and engaging teen community within the

library is enhanced.

Introduction

Public libraries

have long been essential providers of youth services, offering not only access

to information and fostering multiple literacies, but also cultivating vital

21st-century competencies among young individuals (Abbas & Koh, 2015).

While public libraries are prevalent across the United States, they exhibit

notable variations in capacity and resources. Rural communities, in particular,

confront distinct challenges, including poverty, digital divides, and resource

limitations (Meyer, 2018; Perryman & Jeng, 2020; Real et al., 2014).

Consequently, small rural libraries often grapple with reduced funding, limited

collections, staffing, space, services, and programs.

Given these

constraints, it becomes crucial for small rural public libraries to identify

the unique needs of their community members, enabling them to provide services

efficiently and effectively. Unfortunately, there has been a dearth of

attention directed toward understanding the youth in rural areas and their

utilization, or lack thereof, of public libraries. In light of this, in the

present study, the researchers endeavored to explore the perspectives of teens

regarding their aspirations for public libraries. By understanding what teens

desire to see in these institutions, the researchers aimed to provide valuable

guidance to practitioners and researchers seeking to build a resilient future

for youth services in libraries, particularly in small rural settings. Through

such understanding, libraries can adapt and thrive amidst the challenges,

fostering an environment that caters to the evolving needs of the young

generation.

Literature Review

Teens and Public Libraries

Public libraries

have a long history of serving teens, dating back to the 1800s (Bernier, 2020).

The Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA), a division of the

American Library Association (ALA), was established in the 1960s to provide

resources and support for librarians who work with teens. Public libraries

serve as key players in advancing teens’ educational and well-being interests,

as evidenced in research showing libraries’ support for contemporary youths’

connected learning experiences (Subramaniam et al., 2018), promotion of digital

and data literacy (Bowler et al., 2019; Kelly et al., 2023), and librarians

addressing the health information needs of teens (Knapp et al., 2023; Powell et

al., 2023).

Research in

library and information science (LIS) has shed light on the multifaceted ways

in which teenagers utilize public libraries, especially for the social

opportunities afforded by public libraries. Surveys conducted in both urban and

suburban areas of the United States have revealed that teens frequently turned

to public libraries as invaluable hubs for accessing necessary information

resources, fostering social connections within a safe space, and having a

positive environment for other personal activities (Agosto, 2007). Teens in a

semi-rural area in the United States reported that they use a public library

makerspace to tinker, learn, socialize, and pursue their personal interests (Li

& Todd, 2019). Furthermore, studies conducted in rural areas in Canada have

demonstrated that teens visited public libraries for attending programs,

hanging out, and participating in collaborative learning opportunities (Kelly

et al., 2023; Reid & Howard, 2016).

To enhance the

services for teens, researchers have delved into the various features that

teens desire in public library spaces. In studying 25 newly constructed and

renovated public libraries in the United States, Agosto et al. (2015)

highlighted the importance of providing comfortable and inviting physical

spaces, meeting teens’ information needs, and offering many opportunities for

both leisure and academic activities. Similarly, Cook et al. (2005) found that

factors such as hosting teen-only events, providing food options, and offering

general amenities were positively correlated with urban teens’ positive

perceptions of libraries. Teen librarians also shared a set of practices that

contributed to a positive teen library experience, including building a

welcoming teen space that fosters ownership and social interactions, treating

teens with respect, and focusing on teens’ interests (Ornstein & Reid,

2022).

While many

studies have reported positive library experiences among teens, research also

shows conflicting results. For instance, Howard (2011) showed that while teens

were generally satisfied with their local public libraries, the focus group

discussions among teens revealed some dissatisfaction. Howard argued that the

status quo in teen spaces might meet what teens considered normal, but it may

not be ideal for them. Multiple factors contributed to teen dissatisfaction

with libraries. Abbas et al. (2008) surveyed over 4,000 teens in western New

York state, revealing that one of the major contributing factors to library

non-use was the lack of convenience. Outdated or irrelevant technology can be

off-putting for teens in urban areas (Agosto et al., 2016; Meyers, 1999).

Library staff who are distant, strict, or impatient with teens can negatively

impact their impressions of the library and deter them from using it (Agosto

& Hughes-Hassell, 2010; Howard, 2011). In addition, library collections

that do not address issues relevant to specific teen demographics and cultural

identities can make teens feel disconnected from their libraries (Agosto &

Hughes-Hassell, 2010; Meyers, 1999). Teens and tweens who are Black,

Indigenous, and People of Color chose not to use public libraries because of

perceived risks of not meeting institutional policies, rules, and behavioural

expectations (Gibson et al., 2023).

The current

literature further identifies a significant contributing factor to teens’

non-use of libraries – library spaces. Meyers (1999) found that teens perceived

library spaces as “dull”, morgue-like, “boring”, and not designed for teens’

needs. Two decades later, research findings concerning teens’ perceptions of

library spaces remain consistent. Inadequate library spaces and equipment for

teens continue to negatively affect teens’ library use (Howard, 2011). Bishop

and Bauer (2002) found that young adults in both urban and rural areas

considered an attractive teen library space as the most important factor in

their library use. Cook et al. (2005) found that early teens viewed inviting

and teen-only areas as positive indicators of libraries. This result was

further supported by Bernier et al.’s (2014) survey of 411 libraries, which

found a positive correlation between the amount of library space dedicated to

young adults and the level of library participation from teens. Bernier (2010)

emphasized the importance of youth input and participation in space design to

meet their aesthetic needs. Therefore, it is crucial to consider teens’

perspectives when designing library spaces to enhance their library use.

Rural Public Libraries

Public libraries

are important institutions in rural communities, playing crucial roles beyond

book repositories. Rural libraries are trusted resource providers for various

information needs, assist patrons in finding print and digital resources, and

serve as community centers where people gather and meet others (Grove &

Brasher, 2020). Public libraries in rural areas also have the capacity to

contribute to local economic growth by supporting job skills training and small

businesses development (Hughes & Boss, 2021; Mehra et al., 2017; Real &

Rose, 2017). Additionally, public libraries may be the only institutions in

rural areas that provide free access to computers and the Internet, and support

for technology skills (Real & Rose, 2017). Rural libraries offer health and

wellness programs that make positive impacts on rural residents (Flaherty &

Miller, 2016; Lenstra et al., 2022).

However,

research has shown that rural libraries in the United States face many

challenges. Staffing and funding are among the most often reported challenges.

Fischer (2015) reported staffing challenges and limited funding in rural and

small libraries, including a lack of librarians with master’s degrees, even

though the survey findings showed that there has been some improvement in

conditions in these rural and small libraries. Access to technologies and the

Internet is limited in rural communities. According to Real and Rose (2017),

rural libraries offered the fewest public access computers overall, and

Internet speed was often inadequate to meet the needs of patrons. Situated in

this challenging environment, services to children and teens suffer tremendously.

Real and Rose noted that rural libraries tended to have fewer programs related

to science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics (STEAM), and fewer

formal after-school programs, like homework help, compared to their urban

counterparts.

To tackle the

challenges encountered by rural libraries, researchers underscore the

importance of community engagement and the implementation of innovative

outreach strategies. Reid and Howard (2016) highlighted the deployment of

mobile library services, book delivery services, and the establishment of

satellite library branches in serving community members in rural areas.

Additionally, Kelly et al. (2023) demonstrated that a partnership between rural

libraries and local community organizations provided local youth access to

laptops, enabling their participation in coding clubs hosted by the libraries.

Despite the longstanding tradition of public libraries serving teenagers,

research focused on teen services is clearly limited, with an even greater

scarcity of studies centered on rural teen populations. To address the

identified research gap in the current literature in LIS, this study aims to

explore the following research question:

RQ: How would

teens design their desired teen space in a small rural public library?

Methods

The use of

surveys, focus groups, and interviews has been common in LIS research to

explore the opinions and preferences of teenagers regarding libraries. However,

visual participatory research, which involves gathering visual data like

photographs and drawings created by the participants, has been an underutilized

method (Weber, 2008). In LIS, there has been an increasing interest in

employing photography as a visual method to enhance qualitative data collection

(e.g., Agosto & Hughes-Hassell, 2005; Barriage, 2021; Li & Todd, 2019).

However, the application of drawings as a data collection method has received

limited attention, with Hartel’s (2014) research being an exception, wherein

college students’ drawings were used to illustrate their conceptualizations of

information. The use of visual data collection methods has proven to be a

valuable tool in research as it enables participants to engage more deeply with

research questions (Gauntlett, 2005). In particular, young people tend to be

more attentive and involved when visual activities are included (Hartel, 2014;

Subramaniam, 2016). According to Weber (2008), images encourage participants to

consider research questions from diverse perspectives, beyond what is possible

with writing or speech. Researchers can gain a more comprehensive understanding

of participants' viewpoints through visual data (Weber, 2008; Woodgate et al.,

2017). In this study, we aimed to broaden previous research by employing this

method to gain insight into the library images that young people aspire to have

in their communities.

Data Collection

Data were collected in a small rural area in the United States. The

researchers collaborated with the principal and art teacher at a local middle

school to gather data. Consent forms were distributed to each homeroom in the

middle school. In all, 27 8th graders (ages 13 to 14) were recruited

to participate in a drawing activity during art class, during which the

researchers were not present. Participants were asked to design their ideal

public library space for teens and write responses to three prompts, which were

to 1) describe the library as it was, 2) describe what you wished the public

library to be, and 3) describe their drawings. These written responses were

requested to help us understand their perceptions of the public library and

what they wanted in their public library. All the drawings were submitted

anonymously. Furthermore, to complement the visual and written data collected

from the drawing activity, two additional teens (ages 13 to 14) were recruited

through convenience sampling, which involved inviting individuals that the

researchers had known, to participate in individual semi-structured interviews.

These interviews allowed researchers to ask follow-up questions, providing

further clarification and validation of emerging themes derived from the

drawing activities. Each interview was conducted virtually and lasted

approximately 30 minutes. See Appendix for the interview questions. This study was approved by the university’s institutional

review board.

Data Analysis

To analyze the

data collected from the drawings, written responses, and interview transcripts,

we imported them into Dedoose, a qualitative data analysis software. We used

the constant comparison technique in the initial rounds of open coding and

axial coding (Charmaz, 2006). Initially, we independently coded the same set of

four participants’ design activity sheets to examine the differences and

similarities of our interpretations of the data. We

discussed each code together and came up with 50 initial codes inductively

(e.g., feeling irrelevant, not having many books, freedom of doing whatever

they want, hanging out, gaming, a colorful place, etc.). These 50 codes

were further grouped into 7 categories, including social interactions, being

kids/freedom to express themselves, relevance, visual appeals,

books/information, learning, and emotions. Then we used another set of six

participants’ data, which were randomly selected from the data, to test the

shared understanding of these emergent themes. Using the Dedoose Training

Center, the code application test results showed that the inter-coder

reliability arrived at an overall Cohen’s Kappa value of 0.46, indicating a

fair agreement (Fleiss, 1971). Codes with a Cohen’s Kappa value less than 0.65

were discussed to reach an agreement. During the discussion of different

interpretations of the excerpts and codes, if a code was updated, the

researchers went through all the data to compare them to the newly modified

code. When a new code was generated, comparisons between codes were also made. Through meetings and discussions, the researchers

identified a total of four categories – activities, amenities, books, and

visual design – that were collectively agreed upon to answer the research

question explored in this study. When comparing the generated codes from

drawings and written responses to those from the interviews, no discernible

differences in results were observed between these two data collection methods.

All names reported here are pseudonyms that were assigned by the

researchers. All the quotations are verbatim.

Findings

Overall, the

data analysis revealed predominantly negative

perceptions of the local public library among teens. For instance, Jordan

succinctly stated, “not fun,” while Taylor commented on its “gloomy and boreing

[sic]” atmosphere. When prompted to share their ideas on redesigning the

library to appeal to individuals like themselves, their suggestions were

categorized into four themes: activities, amenities, books, and visual design.

Each of these primary themes is described below, accompanied by illustrative

examples.

Desired Library Activities

The data analysis highlighted a major concern among

teens regarding the availability of engaging activities at the library. When

the library failed to offer compelling programs, teens perceived the library as

irrelevant to their interests and needs. For instance, one participant, Avery,

described libraries as “A big buiding [sic] with really nothing to do for

kids.” On the other hand, participants expressed their desires for a library

that catered to their preferences, indicating a need for a space that allowed

for free-choice fun activities, learning opportunities, and social interactions.

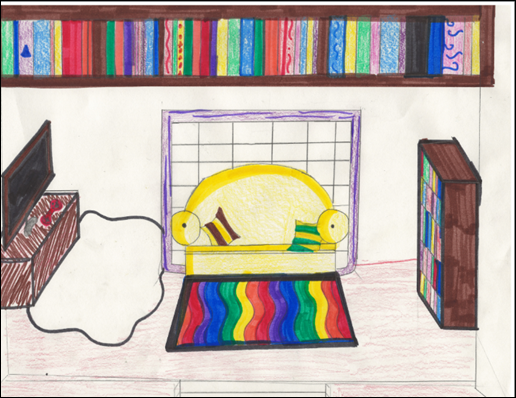

For example, Morgan noted, “My drawing is a trendy library for teens 13-19 to

socialize, study, and have fun.” See Figure 1 below. Similarly, Alex shared: “A

fun place where kids can go to hang have fun and learn.”

Figure 1

Design for teen space (by Morgan).

Twelve teens emphasized the importance of having a dedicated

study area in their ideal library, expressing a desire for study rooms with

tutors and spaces suitable for schoolwork and group activities. Quinn, for

instance, wrote: “I also thought a study room would be nice for doing

schoolwork/group activities.”

In their designs, participants emphasized the

importance of offering spaces for creative expression and entertainment. The

appeal of video games was evident among seven teens, who expressed a desire for

a dedicated game room in the library. Cameron, for example, wrote: “Also a lot

of kids my age like playing video games so I thought a game room would attract

a lot of people.” Charlie in the interview explained: “I think people would probably mostly play games. Maybe

someone plays educational games… that’ll be fun, like people can learn

something and they can play games at the same time.” Intriguingly, two teens

included music rooms in their ideal library design. Cameron highlighted the

popularity of music among young people, stating: “I know a lot of people

(including myself) that enjoy listening/making music, so I thought a music room

would be nice to have.” Rowan expressed a specific desire for “rated-R music.”

Social interactions were also crucial for eight teens

who participated in the drawing activity and two interviewees. Finley expressed

a wish for the library to be “1 cool place where I can go hang out with

friends,” while Skylar indicated that the library could serve as a place to

“make new friends.” In addition to having fun with friends, the teens also

sought support from their peers, as Blake wrote: “Somewhere for teens can go to

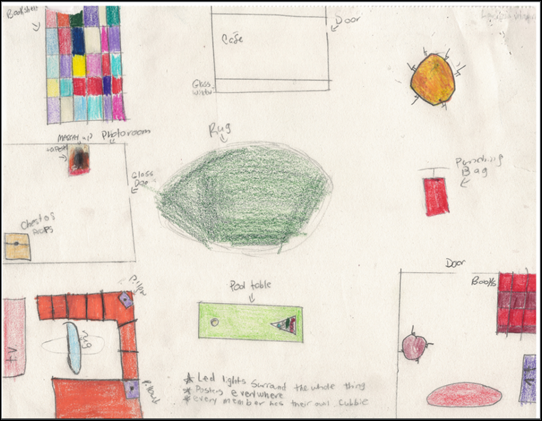

get support from other teens.” This desire for a space to hang out and socialize

was shown in their designs where they drew curved couches at the center of the

teen space, for example, the design from Dakota in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2

Design for teen space (by Dakota).

Desired Library Amenities

Data analysis

revealed that teens expressed a strong desire for convenient and appealing

amenities in the library. These amenities encompassed a range of facilities,

including vending machines, food services, arts and craft tables, ping-pong

tables, large TVs, and comfortable furniture. The teens’ input offered valuable

insights into their vision of the ideal library space, where they could enjoy

various activities and feel comfortable spending time.

Five

participants specifically mentioned the inclusion of food services, such as a

“snack bar” or a “café,” in their designs for the ideal library. For instance,

Emerson creatively envisioned a “secret door” leading to a pantry filled with

an abundant variety of snacks from around the world, highlighting the appeal of

convenient food options within the library setting. The participants’ feedback

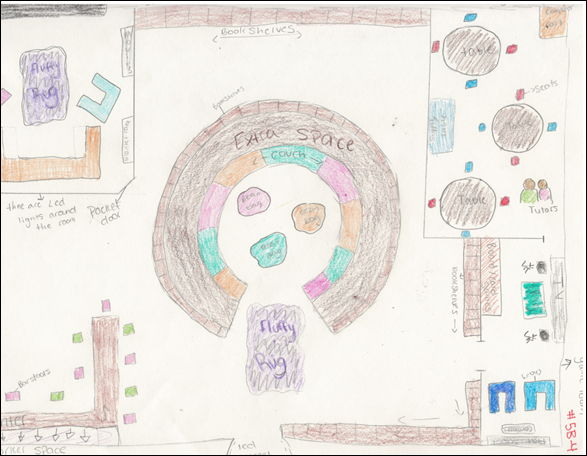

underscores the importance of offering diverse amenities that cater to their

interests and needs. As exemplified below in Figure 3, the amenities featured a

café in the top left corner, a flat screen TV and bean bags in the middle

right-hand section, and lockers for instruments in the bottom right corner of

the dedicated teen space.

Figure 3

Design for teen

space (by Cameron).

Desired Books

Teens’

perceptions of the books housed in the library were diverse, with some

expressing satisfaction with the library’s book collection, while others voiced

concerns about the relevance and variety of books available. The majority of teens described libraries as having an

adequate number of books, with Tom mentioning, “There are a lot of bookshelves

everywhere.” However, one teen pointed out the limitations, stating, “The teen

space is very small...There aren’t many books in it.” Sage further elaborated

that the library should strive to be “a fun place with better books.” This

desire for “better books” might explain the conflicting perceptions, as teens

recognized that libraries contained books, but these books did not always align

with their interests and preferences. In the interview, Charlie explained:

“People still like non-fiction books more...so informational books might be

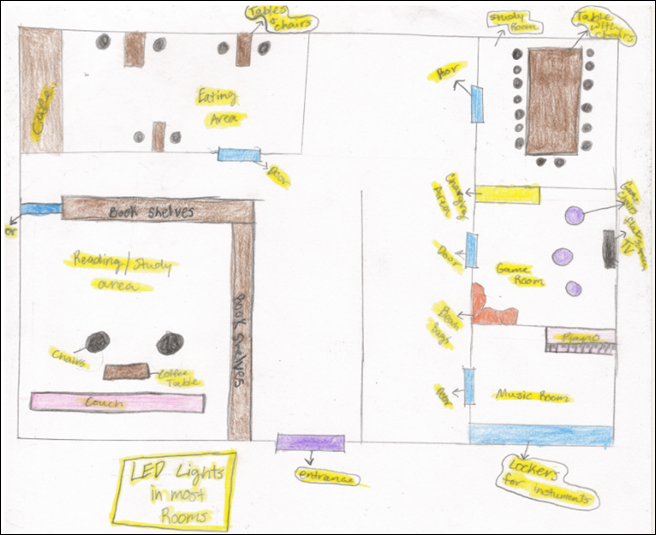

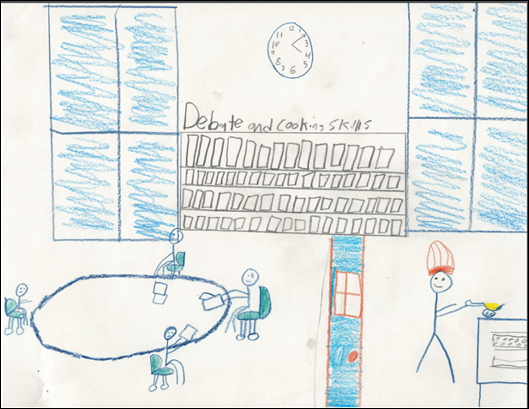

good.” Hayden expressed an interest in books related to debate and cooking

skills in their ideal library design (see Figure 4 below), highlighting the

importance of relevant and engaging content.

Figure 4

Design for teen

space (by Hayden).

It also became

apparent that teens’ interests in reading influenced their perception of

libraries. Quinn, for instance, stated: “I thought the library was only a place

for reading and at the time I didn’t like to read at all.” This showed how a

lack of interest in reading during a particular period led them to perceive the

library solely as a place for reading, reflecting a limited perspective at the

time.

Desired Visual Design

Five teens

expressed the view that libraries were perceived as outdated. Samuel succinctly

described libraries as “bland” and “old,” while Sage shared a similar

sentiment, stating, “In my opinion, it’s kinda vintage and bland.” Conversely,

when prompted to envision their ideal libraries, six teens expressed a strong

desire for libraries to be “trendy” and modern. Blake mentioned the inclusion

of “nice big cool lighting,” while Quinn specifically highlighted a wish for a

“colorful carpet.” Similarly, Morgan wrote “Libraries could be boring to the

eyes; you should also add some color so it can pop eyes.” See Figure 5 below

for an example design that highlighted the desire for colors in the teen space.

Figure 5

Design for teen

space (by Alan).

Discussion

The present

study aimed to understand teenagers’ views on designing the teen space in a

small rural public library in the United States. The desired activities

reported by the teens in this study emphasized the importance of creating a

library space that allows them the freedom to engage in activities that

interest them, such as studying, socializing with friends, playing video games,

and enjoying music. Teens’ insights suggested that the availability of books is

only one aspect influencing teens’ perceptions of libraries. The content of these

books and how well they cater to the diverse interests and passions of young

patrons were equally crucial. The sentiments expressed among teen participants

emphasized the importance of creating visually appealing and dynamic library

spaces for teens. By incorporating engaging activities, well-thought-out

amenities, diverse book collections, and visually appealing designs, libraries

have the potential to attract and resonate with the younger generation.

Particularly in rural libraries that commonly face challenges such as limited

staff and budgeting, knowing teens’ preferences becomes critical for libraries

to prioritize their budget and services to create an inclusive and appealing

environment that meets the needs and desires of their teen patrons.

Overall, the

findings of this study showed that teens in rural areas shared many

commonalities with teens in urban and suburban areas regarding their desired

library space and library uses (Agosto, 2007). Teens’ desire for an attractive

teen space reported in this study aligns with the insights presented by Bishop

and Bauer (2002). Additionally, the findings underscored the importance of

providing a more relevant collection for teens, echoing previous research that

highlighted the disconnect between teens and library collections that fail to

represent their interests and identities (Agosto & Hughes-Hassell, 2010;

Meyers, 1999).

While this study

confirmed many findings from previous research, the researchers noted that

teens in this present study did not strongly express their desires for

libraries to meet their information needs. This finding is different from

previous research in which teens used libraries for information resources

(Agosto, 2007; Agosto et al., 2015). One possible

explanation for this difference could be the limited availability of public

transportation options for teens in rural areas, making it challenging for them

to physically visit libraries, especially when considering the impractical

walking distances involved. Another possible

explanation could be rural teens might have other readily accessible

information sources such as online websites, local community centers, and

school libraries. Further research is needed to understand rural teens’

information practices in their everyday life, so that rural libraries can

provide services that cater to the needs of rural communities.

The findings of

this study have practical implications for youth services librarians to

consider when developing teen spaces and engaging with rural teens. Given the

common challenges of limited resources faced by small and rural libraries, it’s

crucial for librarians to understand the interests and needs of their local

teens, so that tailored programs and services for teens can be provided.

Forming a teen advisory council where teens have a platform to share their

interests and needs can be helpful, and also encourages teens to take on

leadership roles in the ownership of their libraries. Low-cost assessment

methods, such as informal interviews and drawing activities as utilized in this

present study, can also help librarians understand teens’ preferences of

library spaces (e.g., preferences of snack areas and aesthetic design

elements), desired activities (e.g., studying, socializing, gaming, and

relaxation), and reading preferences. Additionally, recognizing the limited

public transportation options in rural communities, libraries can implement

bookmobiles and outreach programs to bring library resources directly to rural

teens and leverage social media sites and virtual programs to connect with

teens. Lastly, as suggested in previous research (Kelly

et al., 2023; Reid & Howard, 2016), rural libraries should build

partnerships with local schools, homeschoolers, and local community

organizations to promote library programs and services for teens, and seek

additional resources, funding, and support for teen programs and services.

Limitations

The researchers

acknowledge several limitations that may impact the scope and depth of the

findings. First, it is important to note that the overall number of drawings

collected from a single grade within a rural school was small and limited,

which may restrict the transferability of the findings to other age groups and

geographic areas. Future research should consider a more diverse sample by

encompassing young people from different age groups and various rural areas.

Second, while

the two interview participants were asked about their use of the local library

and possession of a library card, these questions were not presented to the participants

in the drawing activity. Future research could investigate whether existing

library usage is related to the themes identified in this study’s findings.

Third, the study

relied mainly on data collected from drawings and

accompanying texts, which may offer valuable information but may lack the

richness of in-depth interviews. Visual data, as noted by Literat (2013), can

be highly interpretable, and understanding the context surrounding the creation

of the drawings becomes crucial. Gauntlett (2005) highlighted the importance of

participants interpreting and sharing the meanings of their drawings to avoid

overinterpretation or incorrect interpretation by researchers. Future research

could address this limitation by engaging in more comprehensive interviews to

encourage participants to elaborate on their designs and provide deeper

insights into their perspectives. For instance, understanding what teens

specifically mean by “better collection” would provide a more nuanced

understanding of their desires for library resources.

Last, the study

did not clearly identify which of the four identified categories mattered the

most to the teens. While it is evident that teens desired a variety of

amenities, activities, visually appealing elements, and relevant collections,

the study did not prioritize or rank these preferences. Future research could

invite teens to rank these categories according to their importance, which

would aid librarians in efficiently prioritizing their efforts when developing

teen spaces. Given the potential challenges of limited budgets in small rural

libraries, such rankings would offer valuable guidance for decision making and

resource allocation.

Conclusion

In this exploratory study, we aimed to uncover the

preferences of teens in a rural community regarding their desired features for

the teen space in their local public library. By engaging the teens in

designing their ideal library space, the study identified four major categories

that hold significance for librarians when developing teen spaces. These

categories encompassed activities, amenities, books, and visual designs,

offering valuable insights into teens’ needs and expectations.

The study revealed that teens expressed a strong

desire for a versatile space that can accommodate various activities, including

studying, socializing, gaming, and relaxation. They sought amenities like food

and comfortable furniture to enhance their overall experience. Teens also

yearned for library collections that better align with their interests and

needs, reflecting a desire for resources that resonate with their preferences.

Teens emphasized the importance of a bright and visually appealing space within

the public library. This aesthetic consideration is seen as pivotal in creating

an inviting and attractive environment for teen patrons.

Youth services librarians can utilize these findings

to guide the development of teen spaces that effectively cater to the

preferences of their young patrons. By incorporating the desired activities,

amenities, books, and visually appealing elements, librarians can create an

engaging and relevant library environment that speaks directly to the needs of

teens. Ultimately, the researchers aimed to ensure

that teens find their local public library appealing, inclusive, and

meaningful, a space that enhances their connection with the library and fosters

a sense of belonging within the community.

Funding

This work was

made possible through the support of Pennsylvania Western University (formerly

Clarion University of Pennsylvania) under the University Community Fellow

Program Grant.

Author Contributions

Xiaofeng Li:

Conceptualization, Formal analysis (equal), Funding acquisition (equal),

Methodology (equal), Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

(lead) YooJin Ha: Data curation, Formal analysis (equal), Funding

acquisition (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – review & editing Simon

Aristeguieta: Formal analysis (equal), Funding acquisition (equal),

Methodology (equal), Writing – review & editing

References

Abbas, J., Kimball, M., Bishop, K., & D’Elia, G. (2008). Why youth

do not use the public library. Public Libraries, 47(1), 80–86.

Abbas, J., & Koh, K. (2015). Future of

library and museum services supporting teen learning: Perceptions of

professionals in learning labs and makerspaces. The Journal of Research

on Libraries and Young Adults, 6, 1–24.

Agosto, D. E. (2007). Why do teens use

libraries? Results of a public library use survey. Public Libraries,

46(3), 55–62.

Agosto, D. E., Bell, J. P., Bernier, A., &

Kuhlmann, M. (2015). “This is our library, and

it’s a pretty cool place”: A user-centered study of public library YA spaces.

Public Library Quarterly, 34(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2015.1000777

Agosto, D. E., & Hughes-Hassell, S. (2005). People,

places, and questions: An investigation of the everyday life

information-seeking behaviors of urban young adults. Library &

Information Science Research, 27(2), 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2005.01.002

Agosto, D. E., & Hughes-Hassell, S. (2010). Revamping

library services to meet urban teens’ everyday life information needs and

preferences. In D. E. Agosto & S. Hughes-Hassell (Eds.), Urban teens

in the library: Research and practice (pp. 23–40). American Library

Association.

Agosto, D. E., Magee, R. M., Dickard, M., & Forte, A. (2016). Teens,

technology, and libraries: An uncertain relationship. The Library Quarterly,

86(3), 248–269. https://doi.org/10.1086/686673

Barriage, S. (2021). Examining young children’s

information practices and experiences: A child-centered methodological

approach. Library & Information Science Research, 43(3),

101106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2021.101106

Bernier, A. (2010). Spacing out with young

adults translating YA space concepts into practice. In D. E. Agosto &

S. Hughes-Hassell (Eds.), Urban teens in the library: Research and practice

(pp. 113–126). American Library Association.

Bernier, A. (Ed.). (2020). Transforming young adult services (2nd

ed.). ALA Neal-Schuman.

Bernier, A., Males, M., & Rickman, C. (2014). “It

is silly to hide your most active patrons”: Exploring user participation of

library space designs for young adults in the United States. The Library

Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 84(2), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1086/675330

Bishop, K., & Bauer, P. (2002). Attracting

young adults to public libraries: Frances Henne/YALSA/VOYA research grant

results. Journal of Youth Services in Libraries, 15(2),

36–44.

Bowler, L., Acker, A., & Chi, Y. (2019). Perspectives

on youth data literacy at the public library: Teen services staff speak out.

The Journal of Research on Libraries and Young Adults, 10(2),

1–21.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide

through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications.

Cook, S. J., Parker, R. S., & Pettijohn, C. E. (2005). The public

library: An early teen’s perspective. Public Libraries, 44(3),

157–161.

Fischer, R. K. (2015). Rural and small town library management

challenges. Public Library Quarterly, 34(4), 354–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2015.1106899

Flaherty, M. G., & Miller, D. (2016). Rural

public libraries as community change agents: Opportunities for health promotion.

Journal of Education for Library & Information Science, 57(2),

143–150. https://doi.org/10.12783/issn.2328-2967/57/2/6

Fleiss, J. L. (1971). Measuring nominal scale agreement among many

raters. Psychological Bulletin, 76(5), 378–382. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031619

Gauntlett, D. (2005). Using creative visual research methods to

understand media audiences. MedienPädagogik: Zeitschrift Für Theorie Und

Praxis Der Medienbildung, 9, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.21240/mpaed/09/2005.03.29.X

Gibson, A. N., Hughes-Hassell, S., & Bowen, K. (2023). Navigating ‘danger zones’: Social geographies of risk and

safety in teens and tweens of color information seeking. Information,

Communication & Society, 26(8), 1513–1530. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2021.2013920

Grove, S. A., & Brasher, N. (2020). The

role of rural public libraries in providing access to online government

services. Center for Rural Pennsylvania. https://www.rural.pa.gov/getfile.cfm?file=Resources/PDFs/research-report/Rural-Libraries-exec-sum-2020.pdf&view=true

Hartel, J. (2014). Drawing information in the classroom. Journal of

Education for Library and Information Science, 55(1), 83–85.

Howard, V. (2011). What do young teens think about the public library? The

Library Quarterly, 81(3), 321–344. https://doi.org/10.1086/660134

Hughes, C., & Boss, S. (2021). How rural

public libraries support local economic development in the Mountain Plains.

Public Library Quarterly, 40(3), 258–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2020.1776554

Kelly, W., McGrath, B., & Hubbard, D. (2023). Starting

from ‘scratch’: Building young people’s digital skills through a coding club

collaboration with rural public libraries. Journal of Librarianship and

Information Science, 55(2), 487–499. https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006221090953

Knapp, A. A., Hersch, E., Wijaya, C., Herrera, M. A., Kruzan, K. P.,

Carroll, A. J., Lee, S., Baker, A., Gray, A., Harris, V., Simmons, R., Kour

Sodhi, D., Hannah, N., Reddy, M., Karnik, N. S., Smith, J. D., Brown, C. H.,

& Mohr, D. C. (2023). “The library is so much more than books”:

Considerations for the design and implementation of teen digital mental health

services in public libraries. Frontiers in Digital Health, 5,

1183319. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2023.1183319

Lenstra, N., Slater, S., Pollack Porter, K. M., & Umstattd Meyer, M.

R. (2022). Rural libraries as resources and partners

for outside active play streets. Health Promotion Practice,

15248399211073602. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248399211073602

Li, X., & Todd, R. J. (2019). Makerspace opportunities and desired

outcomes: Voices from young people. The Library Quarterly, 89(4),

316–332. https://doi.org/10.1086/704964

Literat, I. (2013). “A pencil for your

thoughts”: Participatory drawing as a visual research method with children and

youth. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 12(1),

84–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691301200143

Mehra, B., Bishop, B. W., & Partee II, R. P. (2017). Small business perspectives on the role of rural libraries

in economic development. Library Quarterly, 87(1), 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1086/689312

Meyer, J. (2018). Poverty and public library usage in Iowa. Public

Library Quarterly, 37(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2017.1312193

Meyers, E. (1999). The coolness factor: Ten libraries listen to youth. American

Libraries, 30(10), 42–45.

Ornstein, E., & Reid, P. H. (2022). ‘Talk to

them like they’re people’: A cross-cultural comparison of teen-centered

approaches in public library services. Journal of Librarianship and

Information Science, 54(3), 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006211020090

Perryman, C. L., & Jeng, L. H. (2020). Changing models of library

education to benefit rural communities. Public Library Quarterly, 39(2),

102–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2019.1621736

Powell, T. W., Smith, B. D., Offiong, A., Lewis, Q., Kachingwe, O.,

LoVette, A., & Hwang, A. (2023). Public librarians: Partners in adolescent

health promotion. Public Library Quarterly, 42(4), 361–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2022.2107349

Real, B., Bertot, J. C., & Jaeger, P. T. (2014). Rural public

libraries and digital inclusion: Issues and challenges. Information

Technology & Libraries, 33(1), 6–24. https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v33i1.5141

Real, B., & Rose, R. N. (2017). Rural

libraries in the United States: Recent strides, future possibilities, and

meeting community needs. ALA Office for Information Technology Policy. https://www.ala.org/advocacy/sites/ala.org.advocacy/files/content/pdfs/Rural%20paper%2007-31-2017.pdf

Reid, H., & Howard, V. (2016). Connecting

with community: The importance of community engagement in rural public library

systems. Public Library Quarterly, 35(3), 188–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2016.1210443

Subramaniam, M. (2016). Designing the library of

the future for and with teens: Librarians as the “connector” in connected

learning. Journal of Research on Libraries & Young Adults. http://www.yalsa.ala.org/jrlya/2016/06/designing-the-library-of-the-future-for-and-with-teens-librarians-as-the-connector-in-connected-learning/#_edn7

Subramaniam, M., Scaff, L., Kawas, S., Hoffman, K. M.,

& Davis, K. (2018). Using technology to support equity and inclusion in

youth library programming: Current practices and future opportunities. The Library Quarterly, 88(4), 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1086/699267

Weber, S. (2008). Visual images in research. In J. Knowles & A.

Cole, Handbook of the arts in qualitative research: Perspectives,

methodologies, examples, and issues (pp. 42–54). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226545.n4

Woodgate, R. L., Zurba, M., & Tennent, P. (2017). Worth a thousand

words? Advantages, challenges and opportunities in

working with photovoice as a qualitative research method with youth and their

families. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(1), 126–148.

https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-18.1.2659

Appendix

Interview

Questions

- Tell us a little bit about yourself. What grade are you in?

- How do you usually use your local public library? And why? Do you

have a library card?

- Show and tell us what you drew. Let the participants lead the talk.

The interviewer will follow up with the why questions.

- Pay attention to the space and design elements - what materials

and furniture do they want to see in the space? What kind of space design

and arrangement?

- Pay attention to the service/programming elements - what kinds of

services and programs do they mention when they talk about their

pictures?

- Tell us one thing that you want to see or want to do in our public

library.