Research Article

Research Assessment Reform,

Non-Traditional Research Outputs, and Digital Repositories: An Analysis of the

Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) Signatories in the United Kingdom

Christie Hurrell

Associate Librarian

Libraries and Cultural

Resources

University of Calgary

Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Email: achurrel@ucalgary.ca

Received: 21 July 2023 Accepted: 11 Oct. 2023

![]() 2023 Hurrell.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2023 Hurrell.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30407

Abstract

Objective – The goal of this

study was to better understand to what extent digital repositories at academic

libraries are active in promoting the collection of non-traditional research

outputs. To achieve this goal, the researcher examined the digital repositories

of universities in the United Kingdom who are signatories of the Declaration on

Research Assessment (DORA), which recommends broadening the range of research

outputs included in assessment exercises.

Methods – The researcher

developed a list of 77 universities in the UK who are signatories to DORA and

have institutional repositories. Using this list, the researcher consulted the

public websites of these institutions using a structured protocol and collected

data to 1) characterize the types of outputs collected by research repositories

at DORA-signatory institutions and their ability to provide measures of

potential impact, and 2) assess whether university library websites promote

repositories as a venue for hosting non-traditional research outputs. Finally,

the researcher surveyed repository managers to understand the nature of their

involvement with supporting the aims of DORA on their campuses.

Results – The analysis found that almost all (96%) of the 77

repositories reviewed contained a variety of non-traditional research outputs,

although the proportion of these outputs was small compared to traditional

outputs. Of these 77 repositories, 82% featured usage metrics of some kind.

Most (67%) of the same repositories, however, were not minting persistent

identifiers for items. Of the universities in this sample, 53% also maintained

a standalone data repository. Of these data repositories, 90% featured persistent

identifiers, and all of them featured metrics of some kind. In a review of

university library websites promoting the use of repositories, 47% of websites

mentioned non-traditional research outputs. In response to survey

questions, repository managers reported that the library and the unit

responsible for the repository were involved in implementing DORA, and managers

perceived it to be influential on their campus.

Conclusion – Repositories in

this sample are relatively well positioned to support the collection and

promotion of non-traditional research outputs. However, despite this

positioning, and repository managers’ belief that realizing the goals of DORA

is important, most libraries in this sample do not appear to be actively

collecting non-traditional outputs, although they are active in other areas to

promote research assessment reform.

Introduction

Universities,

governments, and funders in many jurisdictions are increasingly investing time,

resources, and energy into changing the way that researchers and the outputs of

research are assessed for rewards such as grants, hiring, promotion, and

tenure. Traditional means of assessing the outputs of research, and by proxy

the researchers producing these outputs, have relied on a limited set of

outputs (primarily peer-reviewed journal articles, books, and monographs) as

well as a narrow range of metrics to measure those outputs (primarily

quantitative bibliometrics in many fields, or factors such as the prestige of a

press in others). Increasingly, it is being recognized that limiting the

assessment of research to these outputs and metrics is inequitable and does not

align with the stated mission and goals of many actors in the research

ecosystem. An early and highly influential force in this shift is the

Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA), which developed out of a scholarly

conference held in 2012. Along with a suite of other recommendations, DORA

pushes institutions and funders to consider a wider range of research outputs

in research assessment (San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment,

2012).

Widening what is

considered a “research output” outside of the traditional paradigm of

peer-reviewed journal articles, books, monographs, and conference publications

presents challenges. Non-traditional research outputs can take a variety of

forms, such as digital collections, GIS projects, audio-visual materials,

datasets, or code. Due to their diversity, these outputs are unlikely to find a

home with established scholarly publishers (Library Publishing Coalition

Research Committee, 2020). As such, researchers who produce non-traditional

research outputs may face barriers to showcasing these items to knowledge

users, peers, or assessors in their institutions or beyond.

Digital

repositories hosted by academic libraries are unlike traditional scholarly

publishers in that they can typically host and preserve a wide variety of

content and format types, and they are not constrained by the profit motive of

most academic publishers. Additionally, many repositories have features to

track a variety of usage metrics, such as permanent identifiers to help make

outputs more discoverable. Staff in academic libraries can also advise

researchers on topics including copyright, preservation, and impact assessment.

As such, institutional repositories may be well placed to help facilitate the

recognition of non-traditional outputs in research assessment. However, it is

unclear to what extent academic libraries are positioning research repositories

as a solution to this challenge, particularly among institutions that have

publicly committed to enacting the recommendations of DORA.

This study

examined the digital repositories of universities in the United Kingdom that

are signatories of DORA. The goals of this exploratory study were to 1)

characterize the types of outputs collected by research repositories at DORA-signatory

institutions and their ability to provide measures of potential impact, 2)

assess whether university library websites promote repositories as a venue for

hosting non-traditional research outputs, and 3) survey repository managers to

understand the nature of their involvement with supporting the aims of DORA on

their campuses.

Literature Review

Research Assessment and the Impetus for Reform

The push towards

reforming the way research is assessed has been spurred on by policies of

funders worldwide, by institutions, and by researchers themselves. These groups

are reacting to a substantial body of research that demonstrates major

limitations in the way research and researchers have traditionally been

assessed. One of the major targets of this criticism has been the Journal

Impact Factor (JIF), a metric that was originally created as a tool to help

librarians make journal selection decisions by quantifying the frequency with

which the “average article” in a journal has been cited in the past two years

(Garfield, 2006). Over the years, its use has evolved, such that many in the

research community use it as a simple proxy for journal quality, and by

extension, for quality of individual journal articles and even individual

researchers. This is despite well-documented limitations of this metric,

including that citation distributions within journals are highly skewed, that

impact factors can be manipulated by unethical editorial practices, and that

the data used to calculate journal impact factors are neither transparent nor

open to the public (Sugimoto & Larivière, 2017). Even when used

appropriately, the journal impact factor only captures a narrow portion of

potential research impact; namely, impact on scholarship in the form of

citations.

The shortcomings

of the Journal Impact Factor for research evaluation can be seen as the tip of

an iceberg of well-documented biases that disproportionately impact scholars

who are not English-speaking White men in all parts of the research ecosystem

(see, e.g., Caplar et al., 2017; Chawla, 2016a; Fulvio et al., 2021; Mason et

al., 2021). These biases influence the ability of scholars to enter academia,

publish and disseminate scholarship, progress through tenure and promotion,

receive funding, and be competitive for recognition and awards (Inefuku &

Roh, 2016). Additionally, the profit-seeking paradigm of traditional scholarly

publishers creates artificial scarcity and uses gatekeeping mechanisms to limit

the formats, perspectives, and volume of scholarship that is published through

their channels (Suber, 2012). This paradigm particularly disadvantages scholars

whose most important contributions may come in formats such as software, code,

datasets, or practice-based research outputs created with or for community

partners (Chawla, 2016b; Parsons et al., 2019; Savan et al., 2009).

The Role of Non-Traditional Outputs and Impacts in Research Evaluation

Despite not

being widely accepted in traditional research evaluation exercises, there is

evidence that sharing research outputs such as datasets, code, and grey

literature can be very important in a variety of ways, including contact and

collaboration with a broader range of colleagues, an improvement in the

reproducibility of research, influence on policy and practice, and, as citation

practices for these outputs mature, increased measures of impact in the form of

citations or altmetrics (Lawrence et al., 2014; Piwowar et al., 2007; Van

Noorden, 2013; Vandewalle, 2012). The emerging evidence around the potential

benefits of making these outputs more visible and discoverable has led

libraries to pursue means of hosting and preserving them, although this endeavor

is not without challenges (Burpee et al., 2015).

In light of this evidence, and to align with current

institutional initiatives around equity, diversity, and inclusion, most calls

to reform the way research is assessed look to broaden both the methods used to

evaluate research as well as the types of research activities evaluated. The

most influential researcher-led initiative in this space, DORA explicitly

rejects the use of metrics such as the Journal Impact Factor in research

assessment, and provides specific recommendations to funding agencies, institutions,

publishers, metrics-supplying organizations, and researchers themselves. One of

DORA’s recommendations is that a wider range of research outputs be considered

in assessment exercises (reflecting its origin in the sciences, DORA

specifically mentions datasets and software) as well as a broad range of impact

measures (including influence on policy and practice). Alternative metrics

(known as “altmetrics”) such as mentions in news media, social media, or

citations on Wikipedia have been offered as one method to attempt to quantify a

broader range of impacts, although debate on how to interpret them, and

discussion of their limitations, still exists in the research community. Some

of the drawbacks of altmetrics include their ability to be “gamed,” bias, data

quality, and commercialization (Bornmann, 2014; Priem et al., 2010; Sud &

Thelwall, 2014).

DORA now has

over 20,000 signatories including publishers, institutions, and individuals

from across more than 160 countries (Signers, n.d.). However, it is not the

only influential document expressing dissatisfaction with the current state of

research assessment and making recommendations for change, including broadening

the range of activities that are included. In 2015, UK Research and Innovation

published a report presenting the findings and recommendations of an

independent review of the role of metrics in research assessment entitled The

Metric Tide: Review of Metrics in Research Assessment. That report mentions

a wide range of non-traditional outputs including blog posts, datasets, and

software, and recommends that “the use of DOIs [Digital Object Identifiers]

should be extended to cover all research outputs” in order to

make them more discoverable and trackable (Wilsdon et al., 2015, p. 145). This

recommendation was expanded in a 2022 update of the report to acknowledge the

utility of a wide variety of persistent identifiers (PIDs) for a variety of

outputs (Curry et al., 2022). The same report summarizes the recommendations of

19 documents published by a variety of organizations in the research ecosystem

and notes that most of them “include at least one recommendation on widening

the range of research activities considered by research assessment” (Curry et

al., 2022, p. 68). The most commonly mentioned

non-traditional outputs in these documents are datasets and code as well as

activities such as peer review and mentorship.

A consistent

definition of non-traditional outputs is not present in all

of these documents. The Australian Research Council defines them as

research outputs that “do not take the form of published books, book chapters,

journal articles or conference publications” and names several specific output

types including original creative works, public exhibitions and events,

research reports for an external body, and portfolios (Australian Research

Council, 2019, para. 1). A study examining the research, promotion, and tenure

documents from over 100 North American universities found mention of 127

different types of scholarly outputs, which the researchers grouped into 12

diverse categories (Alperin et al., 2022). These examples make it clear that

researchers are producing a wide variety of items outside of the traditional

paradigm, and that these outputs may be valued—or at least considered—by

research assessors.

Funding agencies

in a wide variety of contexts are also increasingly adjusting their practices

to align with the recommendations of DORA and other research assessment

reforms. A survey completed by 55 funding agencies from around the world in

2020 found that 34% of them had endorsed DORA, and 73% had “adapted their

research assessment systems and processes for different research disciplines

and fields, or where different research outputs are intended” (Curry et al.,

2020, p. 32). Additionally, 76% of respondents were currently assessing

non-publication outputs, with software, code, and algorithms the most commonly mentioned. The Open Research Funders, a group

of philanthropic funders worldwide, published an “Incentivization Blueprint”

that urges funders to “provide demonstrable evidence that, while journal

articles are important, [they] value and reward all types of research outputs”

and promotes research repositories as a way for researchers to disseminate

outputs (Open Research Funders Group, n.d., p. 1). The global charitable

foundation Wellcome Trust developed guidance for organizations they fund that

draws heavily on DORA’s recommendations and suggests that candidates for

recruitment and promotion be encouraged to “highlight a broad range of research

outputs and other contributions, in addition to publications” (Wellcome Trust,

n.d., para. 20).

The Role of Academic Libraries

Simultaneously

with this broad movement to shift the way research is assessed, academic

libraries have been developing and expanding services and roles around

scholarly communication and the research lifecycle. To support what Lorcan

Dempsey (2017) terms the “inside-out library,” libraries have increasingly

developed infrastructure and staff to support outputs at all stages of the

research lifecycle, including non-traditional outputs such as datasets,

preprints, digital collections, audiovisual materials, and more. As part of

this shift, libraries have introduced infrastructure such as institutional

repositories and research data repositories, as well as roles including

scholarly communications librarians, repository technicians, research data

management librarians, and digital preservation specialists. Digital

repositories managed by academic libraries are typically quite flexible in

terms of the file formats they can host and maintain and may have advanced

technological features both to promote discoverability of their contents and to

track and communicate indicators around usage and potential impact of outputs.

Additionally, librarians and other staff supporting these services often bring

with them skills in publishing best practices, digital preservation, copyright,

and impact evaluation that can provide added value to users of repositories and

other library-hosted infrastructure. This has led to calls for more discussion

of how libraries can support the publication of a variety of non-traditional

research outputs that may not align with the activities of traditional academic

publishers (Library Publishing Coalition Research Committee, 2020). Other

researchers have pointed out that libraries may need to invest in training to

better prepare staff to support research evaluation and impact assessment

activities (Nicholson & Howard, 2018).

Some academic

libraries have recognized an opportunity to get more involved with hosting—and

helping to demonstrate the impact of—non-traditional research outputs in their

repositories. In an article published in 2003, when repositories were a

relatively new feature in the academic library environment, Lynch noted that

repositories’ ability to host these new forms had potential to challenge

scholarship’s status quo:

preservability is an essential prerequisite to any claims to scholarly

legitimacy for authoring in [a] new medium; without being able to claim such

works are a permanent part of the scholarly record, it’s very hard to argue

that they not only deserve but demand full consideration as contributions to

scholarship. (p. 330)

Early analyses

of the deployment of institutional repositories at academic libraries focused

primarily on the United States, where assessments showed that repositories did

contain a variety of non-traditional outputs, although the most

commonly included types of materials were versions of articles, along

with student work including electronic theses and dissertations (Bailey et al.,

2006; Lynch & Lippincott, 2005; McDowell, 2007; Rieh et al., 2007). One

2005 study to assess repositories in 13 countries found more variation in

content types, with European repositories being more focused on textual content

types than U.S. repositories and also more likely to

collect metadata-only records than their North American counterparts. The study

showed that repositories in the United Kingdom were comprised of 74% articles,

16% theses and books, and 9% other materials, including data and multimedia (van

Westrienen & Lynch, 2005).

In the decades

since these early analyses, some academic libraries have prioritized the

collection of a diverse range of research outputs in their repositories to

respond to different institutional priorities. For example, the University of

San Diego built on their university’s commitment to community engagement to

prioritize the collection of items created in collaboration with community

groups (Makula, 2019). Similarly, Moore et al. (2020) provide examples from the

University of Minnesota demonstrating how the university’s institutional

repository can support community engagement by hosting and preserving outputs

such as newsletters, reports, and other community-focused publications. A study

tracking access to non-traditional research outputs in one institutional

repository found that four diverse types of outputs were all accessed

frequently in the year after they were deposited, garnering on average between

16–25 page views per month (Kroth et al., 2010).

Libraries have

also begun to see repositories as central not only to hosting non-traditional

outputs, but to demonstrating their impact, due to the variety of metrics

available in many repositories. Kingsley (2020) characterizes this as the

“impact opportunity” for academic libraries and notes that they can build on

their experiences and strengths with research data management and open access

to develop infrastructure and processes to capture non-traditional outputs in

their repositories. However, she also points out that repositories might need

to widen their collections policies to include a broad range of outputs,

metadata-only records, or different content types.

The concurrent

rise in interest in reforming the way research is assessed, along with academic

libraries’ shift towards supporting the outputs of their researchers through

the whole research lifecycle, presents potential synergies. For example, if

universities are moving towards a more inclusive definition of what constitutes

a research output, as well as broadening the ways in which the impacts of

research outputs might be measured, then digital repositories may be able to

assist with this endeavor.

Methods

Data to inform

the research questions of this study were gathered using two methods: analysis

of publicly available website content and a survey of institutional repository

managers. To gather the data, a sample of relevant institutions was developed

using information found on the DORA website. By using the website’s filters,

the researcher was able to develop a list of institutions located within the

United Kingdom that had signed onto DORA. From this list, a subset of 77

universities was generated (non-university organizations such as scholarly

associations, subject-specific research groups, and publishers were excluded).

Website Analysis

From this list of universities, the researcher gathered URLs for each

institution’s repository using OpenDOAR, a global directory of open access

repositories. Using this list, the researcher performed an analysis of three

information sources for each university on the list: an analysis of the

university’s institutional repository, an analysis of the university’s data

repository, and an analysis of university websites describing or promoting the

use of these repositories.

The researcher

visited the public-facing websites of these institutions to analyze the content

and selected features of both institutional and data repositories. The analysis

was conducted in 2022 and followed a structured protocol to collect information

on variables including:

- the types of outputs collected by repositories

- the proportion of various output types contained in repositories

- whether or not repositories accepted metadata-only records

- the types of persistent identifiers (PIDs) created for items

deposited into repositories

- the types of impact metrics available within repositories

The full data

collection protocol can be found in Hurrell (2022).

The researcher

also examined webpages (such as repository policy documents, library guides,

and institutional websites) that provided information about the repositories as

well as guidance and instruction to faculty who might use the repositories to

deposit their work. The researcher scanned these web pages looking for specific

mention of non-traditional research outputs, defined as anything other than

peer-reviewed journal articles, book chapters, monographs, or conference

proceedings. Where specific non-traditional outputs were mentioned, the

researcher kept a tally of which specific outputs were named.

Survey of Repository Personnel

Using the same list of 77 universities mentioned above, and during the content

analysis process already described, the researcher collected contact

information associated with institutional repositories at each institution. An

online survey, administered via the Qualtrics platform, was distributed twice

during an 8-week period in 2022, resulting in a 29% response rate (n=22). The

research was approved by the University of Calgary’s Conjoint Human Research

Ethics Board. A list of all survey questions is available in Hurrell (2022).

The survey consisted of eight questions designed to

elicit additional data about how academic libraries, and more specifically

digital repositories and the staff who support them, have been involved (or

not) in implementing the recommendations of DORA on their campuses; whether or not their repository policies have changed since

becoming a signatory to DORA; and information about other factors affecting

research assessment practices at their institution. Most questions were in

multiple choice format, with additional data gathered through open-ended

options and questions.

Results

Website Analysis

All 77 of the universities in the sample were maintaining a publicly accessible

open access institutional repository at the time of data collection. As is

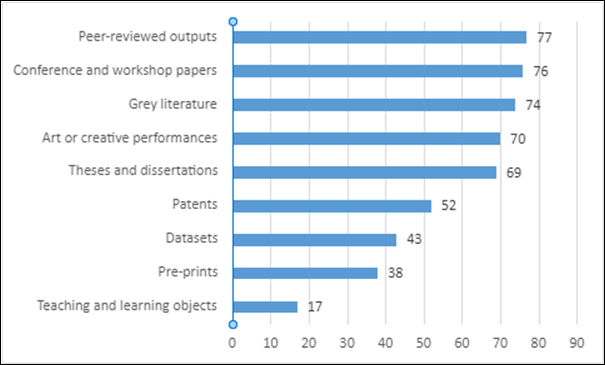

evident from Figure 1, all the institutional repositories contained

peer-reviewed outputs, while 96% of repositories contained non-traditional

outputs of various types, with grey literature (including white papers and

reports), and art or creative performances being the most common. Most

repositories (76%) contained metadata-only records as well as full-text items.

Figure 1

Item types contained in institutional repositories (n=77).

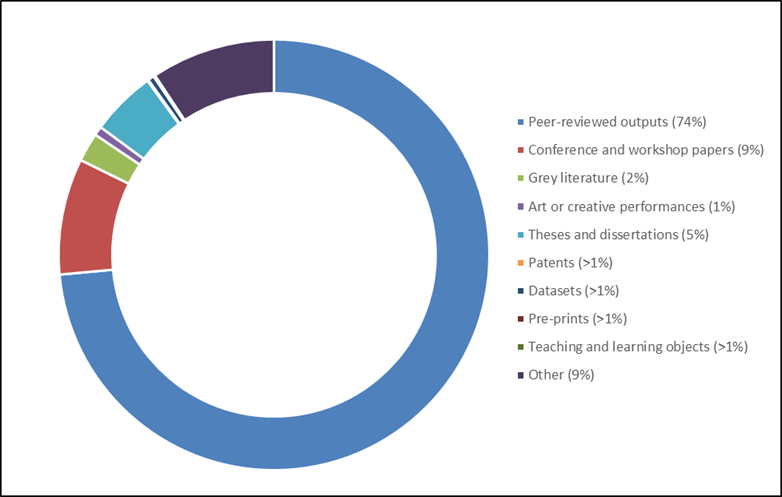

The researcher also attempted to characterize the

proportion of these item types in the repository data set. These data were

difficult to collect accurately, because different

repositories used different schemas for categorizing item types, and many

repositories did not have clear item type categories for outputs such as grey

literature, pre-prints, or teaching and learning objects. Additionally, nine of

the repositories in the dataset could not be searched or browsed by item type.

However, it was clear from the available data that peer-reviewed items made up the majority of content available in the repositories under

study, even though most repositories contained a wide variety of content types

overall. As shown in Figure 2, peer-reviewed outputs comprised 74% of items,

with conference and workshop papers comprising 9%, “other” items comprising 9%,

and theses and dissertations comprising 5%. Other item types were represented

in very small numbers, although it is likely that many item types were

miscategorized as “other.”

Figure 2

Proportion of item types

contained in institutional repositories (n=68).

Persistent identifiers were not minted by the majority of the institutional repositories in this

sample. Most institutional repositories (67%) did not assign any type of

persistent identifier to items, while 24% of repositories minted Handles, and

10% assigned Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs).

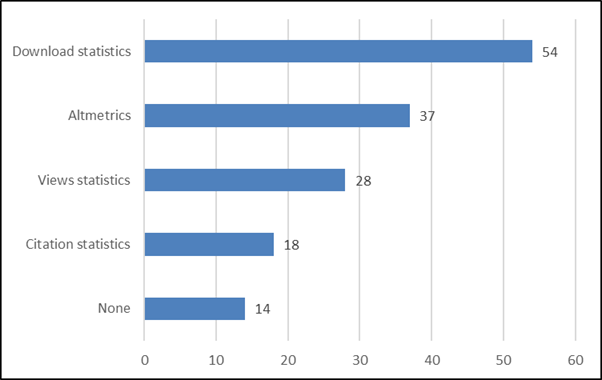

A variety of metrics were available from most

institutional repositories, with download statistics being the most common

type. Where commercial altmetrics (e.g., Altmetric.com or PlumX Metrics) were

integrated into repositories, these were counted separately. A full list of

available metrics is shown in Figure 3.

The researcher also ran

searches for known items from each institutional repository in Google Scholar

to test whether the repository’s content was being indexed. Four known items

were searched from each institutional repository using title searches. Due to

documented issues with Google Scholar’s indexing of grey literature (Haddaway et al., 2015), the

researcher chose to search for grey literature item types in this test. This

simple test revealed that 96% of tested items were discoverable by Google

Scholar.

Figure 3

Metrics available in

institutional repositories (n=77).

In the analysis of

institutional websites to learn whether repositories were promoted as a place

to deposit non-traditional outputs, the researcher found an approximately even

split between websites naming specific non-traditional outputs as items that could

be deposited into institutional repositories (47%, n=36) and websites that did

not mention non-traditional outputs at all (49%, n=38). Three web pages (4%)

could not be assessed because they were not public (i.e., links went to a

password-protected intranet). Of the 36 web pages that named non-traditional

research outputs, a total of 55 unique output types were noted, with datasets,

reports, working papers, images, exhibitions, and software being the most commonly named output types. A complete list of outputs

mentioned, along with their frequency, can be downloaded from Hurrell (2022).

Because research data represent an important type of

non-traditional research output, and due to the growing practice to collect

datasets in repositories specifically designed for this purpose, the researcher

also examined institutional websites to ascertain whether the university had a

separate research data repository. Within the larger sample of 77 universities,

53% (n=41) had a separate data repository. Almost half of these repositories

(49%) contained metadata-only records as well as records with all data files,

while the remaining 51% contained full records with files only.

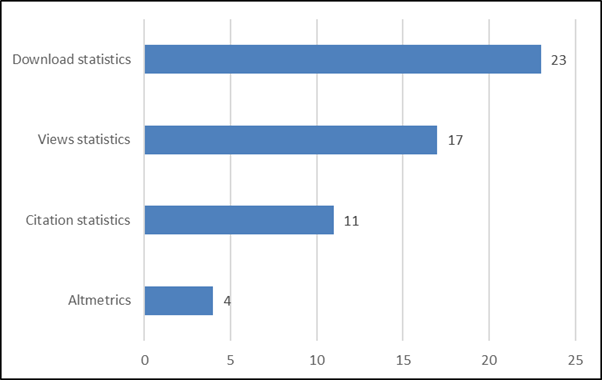

Of the subsample of data repositories, the vast

majority (88%) were assigning DOIs to records, with 5% assigning Handles and

only 10% not issuing any sort of persistent identifier. Similarly, most data

repositories offered at least some metrics, with download statistics again

being the most common. A full list of available metrics is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Metrics available in data

repositories (n=41).

Similar to the test run for

institutional repositories, the researcher searched for known items contained

in the data repositories by searching for specific dataset titles in Google

Dataset Search. Only 34% of data repositories in this sample were discoverable

by Google Dataset Search.

Survey of Repository Personnel

Survey results provided additional details from institutional

repository managers about how DORA was implemented on their university campuses

as well as some context on DORA’s influence on how scholarship is produced and

evaluated at their university. The 22 participants who responded represented

institutions that had signed onto DORA at a variety of points in time, the

earliest being 2014 and the most recent being 2021.

In their

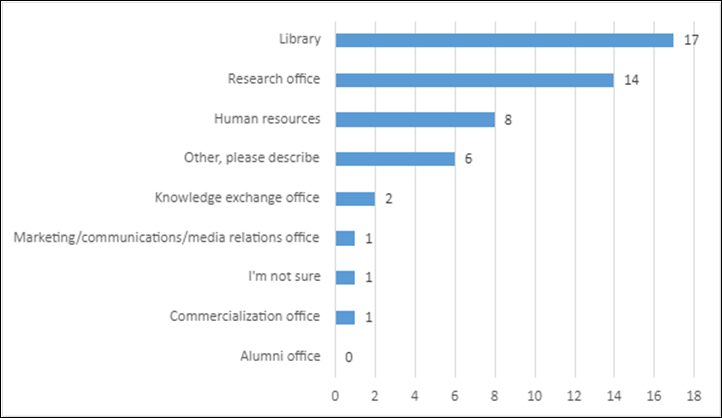

responses, repository managers cited the library as being most often

responsible for implementing DORA, along with their institution’s research

office. Human resources departments and “other” (described

most commonly as committees of academic staff) were less commonly

mentioned, as well as other campus units, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Campus units involved in DORA implementation.

When asked more

specifically if the unit responsible for the institutional repository had been

involved in implementing DORA, 75% of respondents indicated that their unit had

been involved in some fashion, primarily through outreach and engagement;

development of policies, guidelines, or information resources; or through

participation in working groups or committees. A smaller number (10%) indicated

having delivered workshops or instructional modules. Of respondents, 20%

indicated that the institutional repository had expanded its inclusion criteria

to include non-traditional research outputs since signing on to DORA.

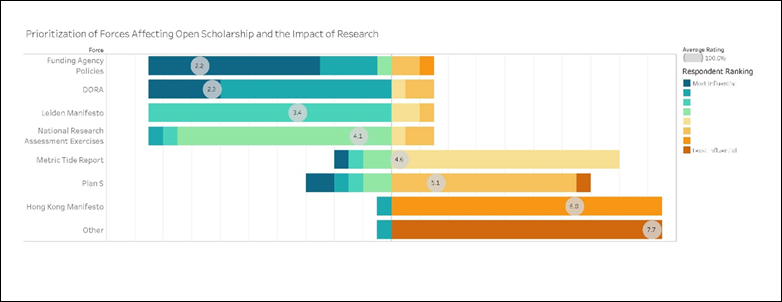

When asked to

rank DORA’s influence on the production and assessment of research as compared

to other forces, repository managers ranked it as being quite influential,

second only to policies of funding agencies. Overall, as shown in Figure 6,

DORA was ranked as having a higher influence than other manifestos and reports

aiming to change research assessment, and higher also than the UK’s national

research assessment exercise, the Research Excellence Framework (REF).

Figure 6

Perceived influence of various factors on the production and assessment

of research.

Discussion

This analysis of

repository websites, institutional websites, and repository managers at

universities in the United Kingdom who are signatories to DORA found that

although most repositories do contain a variety of non-traditional outputs, the

active collection of these materials does not appear to be a strong priority

for most repositories, given the volume of these items compared to traditional

research outputs. This is despite the fact that

repository managers perceive DORA to be an influential factor in research

assessment, and that libraries are given significant responsibilities for

implementing DORA on their campuses.

Repositories

have a number of characteristics that make them ideal

locations for the preservation and discoverability of academic outputs, and

these characteristics were present in many of the repositories included in this

sample. For example, almost all repositories were well indexed in Google

Scholar, making their contents more discoverable, and most incorporated one or

more usage metric. These features may not exist in other online locations such

as faculty, lab, or community-based research unit websites, and certainly

represent a benefit of repositories.

However, past

research has shown that researchers are often not aware of these benefits, or

they do not value them. Even early research interrogating the utility of

repositories suggested that the difficulties faculty associated with using

repositories (such as time, concerns about copyright, unintuitive software, and

inflexible features) vastly outweighed the legitimate yet unappealing benefits

such as preservation and the open access citation advantage (Salo, 2008).

This analysis

also showed that less than half of institutional repositories in the sample

were providing a persistent identifier (PID) to deposited items. PIDs, and

particularly DOIs, are well recognized by researchers and provide benefits

beyond a persistent URL, including assistance in tracking usage and potential

impact (Haak et al., 2018; Macgregor et al., 2023). Perhaps because of their

more recent deployment, software tools used as data repositories in this sample

were much more likely to integrate DOIs, although they were less likely to be

indexed by Google Data Search.

Some

institutions have marketed PIDs, and the metrics they can help drive, to

positive effect. For example, Imperial College London noted a 206% increase in

the deposit of reports in the year following a targeted outreach campaign

promoting the features of their repository, including persistent identifiers

and metrics (Price & Murtagh, 2020). Imperial College London is a signatory

to DORA and thus was included in the present study’s sample; their website was

by far the most detailed and thorough in promoting the repository for

non-traditional outputs.

However, even

those institutions that have found success in promoting their repository for

non-traditional outputs note significant challenges: first, faculty members

often prefer the flexibility, customizability, and perceived ease of using

commercial hosting sites or personal websites for depositing outputs; second,

repository managers acknowledge the resource and time commitments required to

complete other research assessment exercises, especially the UK’s Research

Excellence Framework (REF; Price & Murtagh, 2020). The requirements of the

REF—namely that all journal articles and conference papers be deposited in a

repository—have vastly increased the volume of content in UK repositories but

have also shifted perceptions of the repository from an optional and

potentially exciting tool to a compliance requirement. As one repository

manager noted in an interview, “all the interesting stuff, talking about all

the benefits, or the potential benefits, it's reduced to ... it's just

compliance, compliance, compliance” (as reported in Ten Holter, 2020, p. 7).

The respondents in the Ten Holter study note that the emphasis on depositing

traditional outputs as a requirement has left less time, energy, and interest

amongst repository managers and researchers for using repositories in other

ways. This observation was borne out in the website analysis portion of the

current study: All websites and guides promoting repositories contained

information about how to comply with the REF’s open access requirement and

provided guidance on how to comply with publisher requirements around green

open access and self-archiving of journal articles.

Collecting

non-traditional outputs in repositories requires targeted outreach, engagement,

possible investment in infrastructure changes (such as DOI registration), and

potential changes to policies and workflows. An analysis of over 100 academic

repositories in North America discovered that while 95% of them contained

outputs such as technical reports and working papers, only 63% of repositories

appeared to be making an active effort to collect those items (Marsolek et al.,

2018). The authors suggest that changes to repository collection policies and

scope statements might be required, as well as targeted outreach and metadata

enhancement to make deposited items more discoverable. The present study

reinforces these findings by gathering data from a different jurisdiction to

find similar results.

There are

several limitations to the current study. First, the researcher relied on

information found on institutions’ public websites to gather data about the

contents, features, and functionality of repositories and information used to

promote them. It is possible that this analysis missed important information,

and it is uninformed by the workflows and procedures that underlie the public

interface. The number of repository managers that responded to the survey part

of the study was small, and because participants responded anonymously, links

between the survey results and the website analysis results cannot be drawn.

Future research would benefit from more in-depth engagement with repository

managers, perhaps in the form of interviews. Additionally, further engagement

with researchers in the form of interviews and user experience testing may

surface additional opportunities for developing effective partnerships to

showcase non-traditional research outputs in repositories.

Conclusion

This study

demonstrates that repositories are well equipped to accept non-traditional

research outputs, both from a technical and a policy perspective. Most

repositories already contain a wide variety of non-traditional outputs, but the

volume of these outputs is dwarfed in comparison to traditional, peer-reviewed

outputs. This suggests that repository staff and researchers both put a higher

priority on ensuring that traditional outputs are reflected in institutional

repositories. This is likely influenced by the requirements of existing

research assessment exercises and cultures.

This research

suggests that if repositories are to make a concerted effort to collect and

showcase non-traditional research outputs, they may have to expand beyond the

current focus of ensuring that researchers comply with requirements set out by

funding agencies, governments, and publishers. The UK’s higher education

funding bodies are making changes to the next REF, which will assess research

and impact between 2021 and 2027, including to “recognise and reward a broader

range of research outputs” (Research

England et al., 2023, p. 2). The report goes on to state:

Supporting and

rewarding a diversity of research outputs is important for the progress of

research and its dissemination to diverse audiences. There are important output

types that contribute to the wider infrastructure of research fields that, as

well as being important contributions in their own right,

enable the research of others. Examples include review articles

(including systematic reviews), meta-analyses, replication studies, datasets,

software tools, reagents, translations and critical

editions. Reaching businesses, policymakers and citizens also requires outputs

in different formats, such as policy summaries or video or audio content. (p.

8)

It is too soon

to tell whether these changes, coupled with the incremental yet growing culture

shifts in the research ecosystem towards more holistic and equitable forms of

research assessment, will result in repositories gaining a more central role in

collecting, disseminating, and showcasing non-traditional research outputs.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Dr.

John Brosz for assistance with data visualization.

References

Alperin, J. P., Schimanski, L. A., La, M., Niles, M. T., & McKiernan,

E. C. (2022). The value of data and other non-traditional scholarly

outputs in academic review, promotion, and tenure in Canada and the United

States. In A. L. Berez-Kroeker, B. J. McDonnell, E. Koller, & L. B.

Collister (Eds.), The open handbook of linguistic data management (pp. 171–182). MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/12200.003.0017

Australian Research Council. (2019). Non-traditional research outputs

(NTROs). In State of Australian

university research 2018–19: ERA national report. https://dataportal.arc.gov.au/era/nationalreport/2018/pages/section1/non-traditional-research-outputs-ntros/

Bailey, C. W., Jr., Coombs, K., Emery, J., Mitchell, A., Morris, C.,

Simons, S., & Wright, R. (2006). Institutional repositories (SPEC Kit 292). Association of

Research Libraries. https://publications.arl.org/Institutional-Repositories-SPEC-Kit-292/1

Bornmann, L. (2014). Do altmetrics point to the broader impact of

research? An overview of benefits and disadvantages of altmetrics. Journal

of Informetrics, 8(4), 895–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2014.09.005

Burpee, K. J., Glushko, B., Goddard, L., Kehoe, I., & Moore, P.

(2015). Outside the four corners: Exploring nontraditional scholarly

communication. Scholarly and Research Communication, 6(2),

Article 0201224. https://doi.org/10.22230/src.2015v6n2a224

Caplar, N., Tacchella, S., & Birrer, S. (2017). Quantitative

evaluation of gender bias in astronomical publications from citation counts. Nature

Astronomy, 1(6), Article 0141. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-017-0141

Chawla, D. S. (2016a). Men cite themselves more than women do. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2016.20176

Chawla, D. S. (2016b). The unsung heroes of scientific software. Nature,

529(7584),115–116. https://doi.org/10.1038/529115a

Curry, S., de Rijcke, S., Hatch, A., Pillay, D., van der Weijden, I.,

& Wilsdon, J. (2020). The changing role of funders in responsible

research assessment: Progress, obstacles and the way

ahead. Research on Research Institute. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13227914.v1

Curry, S., Gadd, E., & Wilsdon, J. (2022). Harnessing the Metric

Tide: Indicators, infrastructures & priorities for UK responsible research

assessment. Research on

Research Institute. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21701624.v2

Dempsey, L. (2017). Library collections in the life of the user: Two

directions. LIBER Quarterly: The Journal of the Association of European

Research Libraries, 26(4), 338–359. https://doi.org/10.18352/lq.10170

Fulvio, J. M., Akinnola, I., & Postle, B. R. (2021). Gender

(im)balance in citation practices in cognitive neuroscience. Journal of

Cognitive Neuroscience, 33(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01643

Garfield, E. (2006). The history and meaning of the journal impact

factor. JAMA, 295(1), 90–93. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.1.90

Haak, L. L., Meadows, A., & Brown, J. (2018). Using ORCID, DOI, and

other open identifiers in research evaluation. Frontiers in Research Metrics

and Analytics, 3: Article

28. https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2018.00028

Haddaway, N. R., Collins, A. M., Coughlin, D., & Kirk, S. (2015).

The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey

literature searching. PLoS ONE, 10(9), Article e0138237. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138237

Hurrell, C. (2022). Role of institutional repositories in supporting

DORA. Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/5kjna/

Inefuku, H. W., & Roh, C. (2016). Agents of diversity and social

justice: Librarians and scholarly communication. In K. L. Smith & K. A.

Dickson (Eds.), Open access and the

future of scholarly communication: Policy and infrastructure (pp. 107–127).

Rowman & Littlefield.

Kingsley, D. (2020). The ‘impact opportunity’ for academic libraries

through grey literature. The Serials Librarian, 79(3–4), 281–289.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2020.1847744

Kroth, P. J., Phillips, H. E., & Hannigan, G. G. (2010).

Institutional repository access patterns of nontraditionally published academic

content: What types of content are accessed the most? Journal of Electronic

Resources in Medical Libraries, 7(3), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/15424065.2010.505515

Lawrence, A., Houghton, J., Thomas, J., & Weldon, P. (2014). Where is the evidence? Realising the value

of grey literature for public policy and practice: A discussion paper.

Swinburne Institute for Social Research. http://doi.org/10.4225/50/5580b1e02daf9

Library Publishing Coalition Research Committee. (2020). Library Publishing Research Agenda.

Educopia Institute. http://doi.org/10.5703/1288284317124

Lynch, C. A. (2003). Institutional repositories: Essential

infrastructure for scholarship in the digital age. portal: Libraries and the

Academy, 3(2), 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2003.0039

Lynch, C. A., & Lippincott, J. K. (2005). Institutional repository

deployment in the United States as of early 2005. D-Lib Magazine, 11(9). https://doi.org/10.1045/september2005-lynch

Macgregor, G., Lancho-Barrantes, B. S., & Pennington, D. R. (2023). Measuring the concept of PID literacy: User perceptions and

understanding of PIDs in support of open scholarly infrastructure. Open

Information Science, 7(1): Article 20220142. https://doi.org/10.1515/opis-2022-0142

Makula, A. (2019). “Institutional” repositories, redefined: Reflecting

institutional commitments to community engagement. Against the Grain, 31(5):

Article 17. https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.8431

Marsolek, W. R., Cooper, K., Farrell, S. L., & Kelly, J. A. (2018).

The types, frequencies, and findability of disciplinary grey literature within

prominent subject databases and academic institutional repositories. Journal

of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication, 6(1), Article eP2200. https://doi.org/10.7710/2162-3309.2200

Mason, S., Merga, M. K., González Canché, M. S., & Mat Roni, S. (2021).

The internationality of published higher education

scholarship: How do the ‘top’ journals compare? Journal of Informetrics,

15(2), Article 101155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2021.101155

McDowell, C. S. (2007). Evaluating institutional repository deployment

in American academe since early 2005: Repositories by the numbers, Part 2. D-Lib

Magazine, 13(9/10). https://doi.org/10.1045/september2007-mcdowell

Moore, E. A., Collins, V. M., & Johnston, L. R. (2020).

Institutional repositories for public engagement: Creating a common good model

for an engaged campus. Journal of Library Outreach and Engagement, 1(1),

116–129. https://doi.org/10.21900/j.jloe.v1i1.472

Nicholson, J., & Howard, K. (2018). A study of core competencies for

supporting roles in engagement and impact assessment in Australia. Journal

of the Australian Library and Information Association, 67(2),

131–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2018.1473907

Open Research Funders Group. (n.d.). Incentivizing the sharing of

research outputs through research assessment: A funder implementation blueprint.

https://www.orfg.org/s/ORFG_funder-incentives-blueprint-_final_with_templated_language.docx

Parsons, M. A., Duerr, R. E., & Jones, M. B. (2019). The history and future of data citation in

practice. Data Science

Journal, 18, Article 52. https://doi.org/10.5334/dsj-2019-052

Piwowar, H. A., Day, R. S., & Fridsma, D. B. (2007). Sharing

detailed research data is associated with increased citation rate. PLoS ONE,

2(3), Article e308. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0000308

Price, R., & Murtagh, J. (2020). An institutional repository

publishing model for Imperial College London grey literature. The Serials

Librarian, 79(3–4), 349–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2020.1847737

Priem, J., Taraborelli, D., Groth, P., & Neylon, C. (2010). Altmetrics: A

manifesto. http://altmetrics.org/manifesto/

Research England, Scottish Funding Council, Higher Education Funding

Council for Wales, & Department for the Economy, Northern Ireland. (2023). Research Excellence Framework 2028: Initial

decisions and issues for further consultation (REF 2028/23/01). https://repository.jisc.ac.uk/9148/1/research-excellence-framework-2028-initial-decisions-report.pdf

Rieh, S. Y., Markey, K., St. Jean, B., Yakel, E., & Kim, J. (2007).

Census of institutional repositories in the U.S.: A comparison across

institutions at different stages of IR development. D-Lib Magazine, 13(11/12). https://doi.org/10.1045/november2007-rieh

Salo, D. (2008). Innkeeper at the roach motel. Library Trends, 57(2),

98–123. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.0.0031

San Francisco Declaration on

Research Assessment. (2012). Declaration on Research Assessment. https://sfdora.org/read/

Savan, B., Flicker, S., Kolenda, B., & Mildenberger, M. (2009). How

to facilitate (or discourage) community-based research: Recommendations based

on a Canadian survey. Local Environment, 14(8), 783–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830903102177

Signers. (n.d.). Declaration on Research Assessment. https://sfdora.org/signers/

Suber, P. (2012). Open access. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9286.001.0001

Sud, P., & Thelwall, M. (2014). Evaluating altmetrics. Scientometrics, 98(2),

1131–1143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-013-1117-2

Sugimoto, C. R., & Larivière, V. (2017). Measuring research: What

everyone needs to know. Oxford University Press.

Ten Holter, C. (2020). The repository, the researcher, and the REF:

“It’s just compliance, compliance, compliance.” The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 46(1), Article 102079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.102079

Van Noorden, R. (2013). Data-sharing: Everything on display. Nature, 500(7461),

243–245. https://doi.org/10.1038/nj7461-243a

van Westrienen, G., & Lynch, C. A. (2005). Academic institutional

repositories: Deployment status in 13 nations as of mid 2005. D-Lib Magazine, 11(9).

https://doi.org/10.1045/september2005-westrienen

Vandewalle, P. (2012). Code sharing is associated

with research impact in image processing. Computing in Science &

Engineering, 14(4), 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCSE.2012.63

Wellcome Trust. (n.d.). Guidance for research organisations on how to

implement responsible and fair approaches for research assessment. https://wellcome.org/grant-funding/guidance/open-access-guidance/research-organisations-how-implement-responsible-and-fair-approaches-research

Wilsdon, J., Allen, L., Belfiore, E., Campbell, P., Curry, S., Hill, S.,

Jones, R., Kain, R., Kerridge, S., Thelwall, M., Tinkler, J., Viney, I.,

Wouters, P., Hill, J., & Johnson, B. (2015). The metric tide: Report of

the independent review of the role of metrics in research assessment and

management. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4929.1363