Research Article

Experiences of Visible Minority

Librarians and Students in Canada from the ViMLoC Mentorship Program

Yanli Li

Business and Economics Librarian

Wilfrid Laurier University Library

Waterloo, Ontario, Canada

Email: yli@wlu.ca

Valentina Ly

Research Librarian

University of Ottawa Library

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Email: vly@uottawa.ca

Xuemei Li

Data Services Librarian

York University Library

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Email: lixuemei@yorku.ca

Received: 13 Feb. 2023 Accepted: 21 June 2023

![]() 2023 Li, Ly, and Li. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2023 Li, Ly, and Li. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30325

Abstract

Objective – The purpose of this research is to examine the experiences of mentors

and mentees in the formal mentorship program offered by the Visible Minority

Librarians of Canada Network (ViMLoC) from 2018-2022. Findings from this

research will help mentors and mentees understand how to establish an effective

mentoring relationship. Professional library associations and libraries can

also gain valuable insights to support the visible minority library

professionals within their own mentorship programs.

Methods – Between

2018 and 2022, 113 mentors and 145 mentees participated in four sessions of the

ViMLoC mentorship program. The ViMLoC Mentorship Committee designed and

delivered a survey for mentors and a survey for mentees at the end of each

session. Over four sessions, 81 mentors and 82 mentees completed the surveys,

representing a 72% and 57% completion rate, respectively. Fisher's Exact Tests

were performed to examine if there were significant differences between mentors

and mentees in their perceptions regarding ease of communication, relationship,

helpfulness of mentorship, likeliness of keeping in contact, and importance of

having a visible minority partner.

Results – The

mentees perceived mentoring support to be more helpful than the mentors

perceived it themselves. The mentees were more likely to keep in contact with

their mentors beyond the mentorship program while the mentors did not show as

much interest. The mentees who had a positive experience from the formal

mentorship program were found to be more likely to mentor others in the future,

whereas the same effect did not hold true for the mentors. On the other hand,

some findings were the same for both mentors and mentees. Both stated that

effective communication would facilitate a good mentoring relationship, which

in turn, would lead to positive outcomes and greater likelihood of keeping in

contact beyond the mentoring program. There was also consensus of opinion about

the most important areas of mentoring support and some essential skills for

building a successful mentoring relationship.

Conclusion – This research contributes to the literature by using an empirical

research method and comparative analyses of the experiences between mentors and

mentees over four sessions of the ViMLoC mentorship program. The study focuses

on the perceptions of participants regarding their communication, relationship,

helpfulness of mentorship, associations between their past and present

mentoring experiences, areas of support, importance of having a visible

minority partner, and essential skills for building a successful mentoring

relationship. Mentors and mentees differed significantly in how they perceived

the helpfulness of mentorship support and how likely they would like to

maintain the ties beyond the program. For both sides, effective and easy communication

was found to be critical for building a good mentoring relationship and

achieving a satisfactory experience.

Introduction

The purpose of

this research is to examine the experiences of mentors and mentees who have

participated in the formal mentorship program offered by the Visible Minority

Librarians of Canada Network (ViMLoC). This study focuses on the perceptions of

participants regarding their communication, relationship, helpfulness of

mentorship, associations between their past and present mentoring experiences,

areas of support, importance of having a visible minority (VM) partner, and

essential skills for building a successful mentoring relationship. There are

limited quantitative studies that address formal mentoring relationships in the

field of librarianship, and the existing literature primarily focuses on

American settings (Jordan, 2019). This empirical study compares the experiences

of mentors and mentees, which is rarely seen in other mentorship research.

Findings from this paper will help mentors and mentees understand how to

establish an effective mentoring relationship. Professional library

associations and libraries can also gain valuable insights to support the

visible minority library professionals within their own mentorship programs,

especially in regions where the populations are predominantly Caucasian.

ViMLoC formed in

2012 with a mission to connect, engage, and support visible minority librarians

in Canada. The Employment Equity Act defines visible minorities (VMs) as

“persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or

non-white in colour” (Government of Canada, 2021). Maha Kumaran and Heather Cai

(2015) conducted the first ViMLoC survey in 2013 which reported that VM

librarians lacked mentorship and networking opportunities with other minorities

in the country. Accordingly, the ViMLoC mentorship program was inaugurated in

2013 and on an ongoing basis from 2013-2015 nine pairs were matched, becoming

the first formal mentorship program for VM librarians to be mentored by VM

librarians in Canada (Kumaran, 2013). Many of the formal mentorship programs

available for librarians require association fees, are limited to a small

geographic area, or are tied with other limited opportunities like residency

programs, which are mostly seen at American institutions (Garrison, 2020;

Harper, 2020). One reason for establishing ViMLoC was to improve informal

professional connections (Majekodunmi, 2013); the mentorship program is a

formal way of creating these networking opportunities. ViMLoC is free of charge

and participation in the mentorship program is open to librarians and Master of

Library and Information Science (MLIS) students across Canada who identify as

VMs.

After a hiatus,

the ViMLoC mentorship program was reinitiated in 2018. The ViMLoC Mentorship

Committee (referred to as “the Committee”) recruited VM librarians at every

career stage to be mentors and paired them with mentees. Each session ran for

two months (October-November in 2018, and May-June in 2020, 2021, 2022). The

2018 session occurred at the end of the year from November to December. After

seeing the high demand for visible minorities to mentor each other, the

Committee found there was merit to continuing the mentorship program. They

observed that 58% of the mentees were students and 40% of mentors worked in an

academic library. The Committee decided that offering a mentorship program from

May to June would best suit academic work schedules and be ideal for students

graduating from their programs. Repeating the mentorship program in May-June

2019 would be too soon after the 2018 session closed, so the Committee decided

to postpone the next session until May-June 2020; the subsequent sessions in 2021

and 2022 followed the same timeline. A survey was sent separately to mentors

and mentees at the end of each session. The survey responses were used to

assess the mentorship program and provided rich information about the

mentorship experiences of the participants. The data collected therein formed

the basis of this research.

Literature Review

Barriers for VMs in Librarianship

VMs in the

library profession can face additional invisible obstacles that their Caucasian

counterparts may not. Many of these obstacles have been explained in the

literature. For example, Gohr (2017) identified that new library professionals

looking for their first position in a competitive job market might have to take

on unpaid work experiences to build up their CV. However, for VMs, taking on

unpaid work is considered a privilege and financial barrier that their

Caucasian counterparts might not face as often.

Even after

getting a library job, there are multiple descriptions of workplace barriers

for VM librarians in the literature. A consistently cited barrier is that VM

librarians need to assimilate themselves into a Caucasian-dominated work

culture (Brown et al., 2018; Gohr, 2017; Lee & Morfitt, 2020). The result,

according to Brown et al. (2018), is that VM librarians feel a pressure to

police how they present themselves through their words, behaviour, and

appearance, which can cause personal anguish. For instance, research found that

38.6% of VM academic librarians “did not feel free to speak their mind and

express their views openly,” which adds to that stifling of their true selves

(Kandiuk, 2014, p. 510).

While fitting in

is not the only option, VM librarians who do not conform may face more

microaggressions in the workplace (Brown et al., 2018). Others described how

this work situation could amplify feelings of imposter syndrome (Farrell et

al., 2017; Lee & Morfitt, 2020). Brown et al. (2018), Hathcock (2015),

Johnson (2007), and Thornton (2001) all discussed the feeling of loneliness in

the workplace, either from the physical isolation at work events or from the

emotional isolation of pretending to fit in. Hathcock (2015) further elaborated

on the loneliness of pretending to fit into a structure of White librarianship

and needing someone, like a role model or mentor, to show them how to do so. In

Thornton’s (2001) study of Black female librarians in the US, she determined

that many respondents felt some level of isolation and that was one source for

low levels of job satisfaction. Furthermore, 71% of Black female librarians had

experienced some level of racial discrimination at work, which compounded with

feelings of isolation and negatively impacted morale. Comparatively, in a

Canadian academic setting, Kandiuk (2014) reported that only 42.8% of the VM

academic librarians found that their colleagues were welcoming or somewhat

welcoming to difference and diversity, 23.3% were not or somewhat treated with

respect and as an equal member, and 16.1% felt they were not or only somewhat

valued by work colleagues for their knowledge and work contributions. These

seemingly common experiences of isolation for VMs in libraries can lead to low

morale and negative work environments that make them want to leave the job

and/or the profession altogether (Kendrick & Damasco, 2019; Olivas, 2014;

Thornton, 2001).

Mentorship Identified as a Solution

When referencing

all the barriers and negative experiences of being a culturally diverse library

professional, a common solution proposed by VM librarians throughout the

literature was mentorship. For example, in Johnson’s (2016) interviews of

academic librarians of colour, respondents indicated that a lack of mentorship

was a barrier to their progress in their career and that any form of mentoring

or networking was better than nothing. Echoing that sentiment, in an open-ended

question about how their workplace could support VM librarians in Canadian

academic institutions, the most common survey response was having mentorship

and that “equity-related mentoring” opportunities to support VM librarians

needed to be created (Kandiuk, 2014). Moreover, Olivas (2014) found that many

VM study participants needed to seek mentorship opportunities beyond their

institution because what they received from their library was not adequate.

Many

studies focus on mentoring students before or after LIS (library and

information science) programs to increase the number of VM students and graduates,

which in turn, will increase representation and diverse candidate pool.

Montiel-Overall and Littletree (2010) spoke of a specific program to recruit

and ensure graduation of Latino and Native American in an LIS program; one of

the methods used to ensure high retention was mentorship. McCook and Lippincott

(1997) analyzed American statistics in the 1980s to 1990s to find that LIS

schools that graduated a higher number of diverse students employed mentoring

as a recruitment strategy. The ViMLoC mentorship program also welcomed current

MLIS students who identified as VM to apply as mentees, providing them with an

opportunity to build a professional network and access other resources that

ViMLoC can provide.

Mentorship Benefits for VMs

Since

mentorship has often been proposed as a solution to combat the barriers in the

profession, the benefits of mentorship for VM librarians in these circumstances

need to be elaborated. Some of the more obvious benefits of VM mentorship

listed in the literature are related to getting advice from experts with lived

experience, refining their CV, and career planning and progression (Alston,

2017; Bonnette, 2004; Boyd et al., 2017). However, considering the

circumstances, there is great emphasis on emotional support that mentors have

provided. For example, it could be “a shoulder to cry on, a relatable voice,

and honesty” (Alston, 2017, p. 159). It could also be social supports through

“socialization into the profession” (Boyd et al., 2017, p. 492), or “demystifying

and interpreting library culture and politics and assisting the mentee with

tips on how to work within the given institutional structure,” along with

connecting them with people within their network (Moore et al., 2008, p. 76).

Overall, this blend of practical advice, along with psychosocial support from

mentors has been found to improve job satisfaction for VM librarians (Alston,

2017).

Benefits of VM Mentors

Oftentimes, VM

mentees are paired with Caucasian mentors due to the imbalance of

representation within the profession (Ford, 2018). Many have noted that this

can be problematic as VM mentees may feel the pressure to assimilate more into

the dominant culture of the profession and that Caucasian mentors cannot

provide VM mentees with supports that a VM mentor could (Brown et al., 2018;

Hathcock, 2015). While the effect of mentorship for VMs is profound, it has

been suggested in the literature that having VM mentors providing mentorship to

VM mentees can amplify the benefit. For example, Espinal et al. (2018)

suggested how a mentoring program specifically for VM librarians would be

beneficial to alleviate some of the pressure put on them in a White-dominated profession.

For VM LIS students that had VM mentors, they found that there was a “shared

understanding of their experience” (Hussey, 2006, p. 76) and that VM mentors

can help them navigate through difficult situations based on their own lived

experiences (Hussey, 2006). From their national survey and qualitative

semi-structured interviews of Chinese American librarians, Ruan and Liu (2017)

found that one of the major themes from respondents was mentorship. They

revealed respondents’ praises for the Chinese American Librarians Association

(CALA) mentorship program where Chinese American librarians mentored each

other. They noted that a benefit of VM mentors was providing assistance to

overcome communication and other cultural barriers. Similarly, Moore et al. (2008)

touched upon dealing with situations or issues that would be unique to VMs in

the profession and how the VM mentor could provide advice about how to deal

with it effectively. Furthermore, it has been noted that people from

nonminority groups might not detect microaggressions the way a racialized

person might, but VM mentors are able to validate situations of

microaggressions and provide the VM mentee with reassurance of their

experiences (Alabi, 2015). Anecdotally, Cho (2014) examined his experiences with

other Asian librarian mentors. He found that having VM mentors benefitted him

as it gave him the opportunity to share their experiences together and

reflected upon them. Not only did it benefit the VM mentees, a study of VM

mentors at academic libraries found that mentoring new librarians was

professionally rewarding and increased the VM librarian’s likelihood of

pursuing managerial roles (Bugg, 2016).

While there are

many benefits to be gained from VM mentors, a negative aspect of VMs mentoring

VMs is that there are so few mentors available, especially those with

managerial experiences (Hoffman, 2014; Moore et al., 2008). Thus, extra burden

is placed on VM mentors, especially when mentorship does not count as credited

work. For example, Cooke and Sánchez (2019) highlighted that mentorship was

unpaid volunteer work and did not contribute towards tenure application for

academic librarians. Nevertheless, some VM librarians still took on the added

task of mentorship to ensure the growth of diversity in the profession (Harper,

2020; VanScoy & Bright, 2017).

Communication in a Mentoring Relationship

The literature

about mentoring programs for VMs in libraries focuses more on practical

guidelines that highlight the importance of communication, which is pivotal to

building and maintaining the relationship. For example, the guidance provided

states that regular contact and showing concern allows the VM mentee to openly

share and discuss personal concerns with candour (Abdullahi, 1992; Hernandez,

1994). Likewise, in Harrington and Marshall (2014), the respondents from

Canadian academic libraries highly rated the importance of the following

mentorship activities: sharing experiences, sharing confidential information,

and actively listening to concerns. All these elements go into building a

mentoring relationship through communication. Anecdotally, Olivas and Ma (2009)

described their positive mentoring relationship as VM librarians due to their

“[c]lear communication with each other, on a continual basis” (p. 6) which they

did through emails and phone calls to discuss their professional experiences.

Communication

issues in mentorship can occur due to cross-cultural and intergenerational

differences, among many. Amongst VM librarians there are many factors that can

lead to a breakdown in communication, which becomes a challenge for the

mentoring pair. For example, among the 17 challenges to mentorship listed in

Adekoya and Fasae’s (2021) study of academic librarians in Nigeria,

“ineffective meetings, communication and feedback between the mentor and

mentee” ranked fourth highest. In another study, a respondent identified issues

with communication for the breakdown with their mentor, which created a

negative mentorship experience (Zhang et al., 2007).

Methods

Survey Design and Delivery

To gather

information about the participants’ mentoring experiences and to help improve

the ViMLoC mentorship program, the ViMLoC Mentorship Committee designed and

delivered a survey for mentors and mentees separately at the end of each

session. After ethics approvals from Wilfrid Laurier University and York

University, online survey questionnaires were created using Qualtrics XM. Nine

questions from the surveys used in the first 2013 ViMLoC mentorship session

were slightly updated. An additional 15 new questions were included in the

survey for mentees and mentors respectively, with the researchers referring to

other studies to inform the new questions (Goodsett & Walsh, 2015;

Harrington & Marshall, 2014). The Mentorship Committee also consulted other

ViMLoC committee members for feedback. The survey links were sent to mentors

and mentees via email. The surveys remained open for one month with a reminder

email sent two weeks before the deadline. An informed consent letter was

provided at the start of the survey, which indicated that the participants

could choose not to participate, withdraw at any point, or skip any questions

in the survey. All responses were collected anonymously.

During the

mentorship program, when there was a shortage of mentors or when a mentor had

the expertise that could benefit more than one mentee, one mentor could be

approached to be matched with two mentees. As such, the questionnaires for

mentors were slightly different depending on how many mentees were mentored by

them. The survey for mentors who assisted one mentee contained six

multiple-choice questions about communication, eight multiple-choice questions

about interaction, three multiple-choice questions and one open-ended question

about mentorship experience, and one multiple-choice question and three

open-ended questions about mentorship program assessment (Appendix A). In the survey for mentors who assisted

two mentees, the questions about communication and interactions (Q4-17 in

Appendix A) with the first mentee were repeated for the second mentee. The

survey for mentees included six multiple-choice questions about communication,

eight multiple-choice questions about interaction, two multiple-choice questions

and one open-ended question about mentorship experience, and two

multiple-choice questions and three open-ended questions about mentorship

program assessment (Appendix B).

Data Analysis

The survey

questions were designed to allow comparison of experiences between mentors and

mentees in the program. Four questions (Q13-16) from the mentor survey

(Appendix A) and the mentee survey (Appendix B) were similar, with minor

changes in the wording for the target audience. For instance, in the question

about ease of communication, the mentors were asked “How easy was communication

with your mentee?” This question was reworded for mentees to read “How easy was

communication with your mentor?” Similarly, this research compared the

perceptions of mentors and mentees regarding how they felt about their

relationship with their mentoring partner (mentoring relationship), how helpful

the mentor was in assisting their mentee (helpfulness of mentorship), and how

likely they would connect beyond the program (likeliness of keeping in

contact). These indicators were all measured using a 5-point Likert Scale. For

instance, the response options for the question about ease of communication

included “Very Easy,” “Easy,” “Moderately Easy,” “Difficult,” and “Very

Difficult.”

Moreover,

in-depth analyses were conducted regarding the associations between four items:

ease of communication, mentoring relationship, helpfulness of mentorship, and

likeliness of keeping in contact. This study also examined the associations

between the respondents’ present and previous mentorship experience, and

associations between their present experience and intentions to mentor in the

future. These analyses were based on Fisher's Exact Test, a statistical test

used to determine whether there is a significant association between two

categorical variables if 20% or more of the cells in the contingency tables

have expected frequencies less than five. The Freeman-Halton Extension of the

Fisher's Exact Test for more than 2 x 2 (two-row by two-column) contingency

tables was employed (Ibraheem & Devine, 2013; Kim, 2017). STATA 13 was used

for all data analyses. For the open-ended questions about the skills that are

important for a successful relationship and the most satisfying aspect of the

ViMLoC mentoring program, answers from respondents were coded inductively by

one researcher, with several answers having multiple elements listed, thus

given multiple codes. Subsequently, some codes were aggregated due to

similarity. Another assessment of the responses and second review of the code

assignments was completed. Frequencies for each code were calculated for the

mentor and mentee groups separately.

ViMLoC Mentorship Program Participants and Survey Respondents

From 2018 to

2022, 113 mentors and 145 mentees participated in the ViMLoC mentorship

program. Amongst mentors, the largest three ethnicities were Chinese (38%,

n=43), South Asian (17%, n=19), and Black (10%, n=11). Nearly 60% (n=64) were

working at academic libraries, followed by public libraries (22%, n=25), and

special libraries (17%, n=19). Their experience as a librarian ranged from 2-29

years. Of the 113 mentors, 24% (n=27) were in management positions. Regarding

mentees, Chinese (21%, n=31), South Asian (20%, n=29), and Black (15%, n=22)

were also the most prevalent minorities. Over half the mentees (55%, n=80) were

library school students. This mirrored the finding of Harrington and Marshall

(2014), where library school students were found to expect mentorship

opportunities more than librarians. Those who had librarian experience for less

than five years made up 26% (n=38). Among the mentees, 9% (n=13) had a master's

degree in librarianship from outside Canada. It was noted that a mentor or

mentee might engage in more than one mentoring session, and a mentee might also

serve as a mentor either in different sessions or even within the same session.

The counts and percentages presented above included all repeat participants. As

shown in Table 1, there were 73 participants in 2018, with the greatest number

of mentees (n=48) across the four sessions, which reflected the pressing needs

of visible minority mentees after a few gap years since the first ViMLoC

mentorship program was launched in 2013. The number of participants experienced

a dramatic drop in 2020 due to COVID-19 and bounced back in 2021 and 2022.

Table 1

ViMLoC

Mentorship Program Participants and Survey Respondents

|

Year |

Program Participants |

Survey Respondents |

Survey Completion Rates |

|||

|

Mentors |

Mentees |

Mentors |

Mentees |

Mentors |

Mentees |

|

|

2018 |

25 |

48 |

18 (16) |

25 |

72% |

52% |

|

2020 |

24 |

26 |

16 (2) |

20 |

67% |

77% |

|

2021 |

33 |

39 |

25 (8) |

22 |

76% |

56% |

|

2022 |

31 |

32 |

22 (1) |

15 |

71% |

47% |

|

Total |

113 |

145 |

81 (27) |

82 |

72% |

57% |

Note: The number

in brackets indicates the number of mentors who assisted two mentees.

In total, 81

mentors and 82 mentees completed the surveys, representing a 72% and 57%

completion rate, respectively. Although more mentees participated in the

mentorship program, they had a lower survey completion rate compared to mentors

in all the years, except in 2020 (see Table 1). We analyzed 190 responses,

including 108 responses from mentors and 82 responses from mentees. All

questions were optional, therefore the number of responses for individual

questions varied.

Results

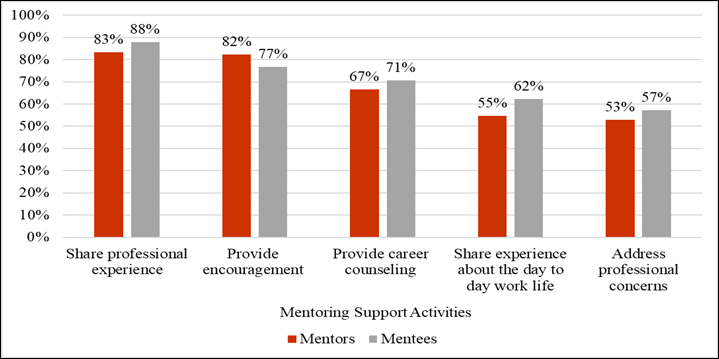

Mentoring Support Activities

The mentees were

asked, “What aspects did your mentor help you with?” This question was reworded

for the mentors to read, “What aspects did you help your mentee with?” Each

group was provided with a list of 20 mentoring support activities to choose

whatever aspects they provided as mentors or received as mentees. Both groups

identified the same five areas of mentorship support as their top experiences:

sharing professional experience, providing encouragement, providing career

counselling, sharing experience about the day-to-day work life, and addressing

professional concerns (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Most reported

five mentoring support activities.

The perspectives

of mentors and mentees were separately analyzed regarding four items: ease of

communication, mentoring relationship, helpfulness of mentorship, and

likeliness of keeping in contact beyond the program. Fisher's Exact Tests were

further conducted to examine if mentors and mentees significantly differed in

their perceptions of each aspect.

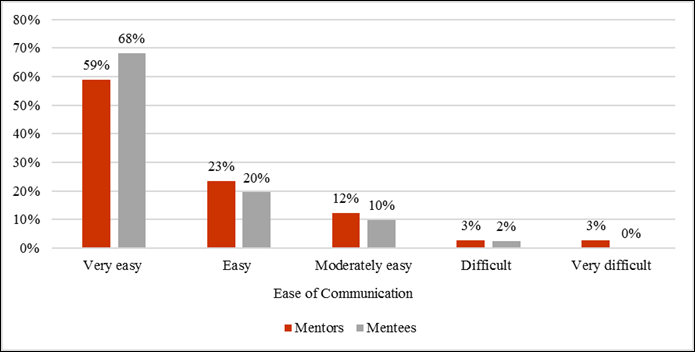

Ease of Communication

The mentoring

pairs communicated in various ways: email, video chat, online chat/instant

messaging, in-person, and telephone. Email and video chat were reported as the

most effective methods of communication. This could be due to the COVID-19

pandemic that made in-person interactions difficult or impossible. The survey

respondents were asked how easy their communication was with the mentoring

partner. Of the 107 responses from mentors, 82% (n=88) indicated “very easy” or

“easy” compared to 88% (n=72) of the 82 responses from the mentees. Meanwhile,

6% (n=6) of the mentor responses indicated “difficult” or “very difficult,”

compared to 2% (n=2) of the mentee responses (Figure 2). The Fisher's Exact

Test was performed to determine if the perspectives of mentors and mentees

significantly differed. The test resulted in a p-value of 0.543, which is

greater than the commonly used significance level of 0.05. Based on this

analysis, the perspectives of the two groups regarding the ease of

communication were not significantly different.

Figure 2

Perceptions of

ease of communication.

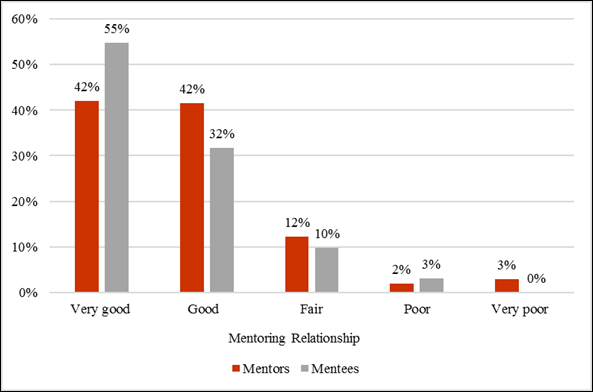

Figure 3

Perceptions of the mentoring relationship.

Mentoring Relationship

There were 106

responses from the mentors and 82 responses from the mentees that described

their mentoring relationships. Of these responses, 87% (n=71) of the mentees

indicated that their mentoring relationship was “very good” or “good,” compared

to 84% (n=88) of the mentors, while 13% (n=11) of the mentees described their

relationship as “fair,” “poor,” or “very poor,” compared to 17% (n=18) of the

mentors (Figure 3). Overall, it seemed that the mentees were more likely to

report a positive relationship than the mentors. However, Fisher's Exact Test

result indicated non-significant differences between the two groups (P = .203).

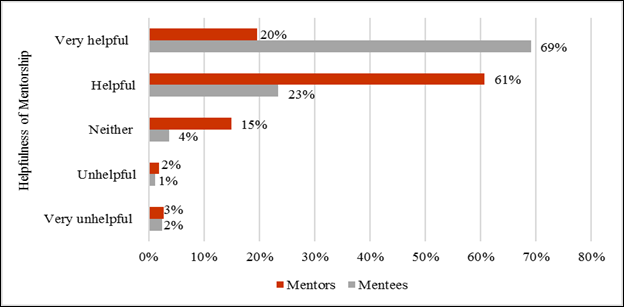

Helpfulness of Mentorship

In the survey

for mentees, they were asked how helpful the mentors had been in assisting

them. In the survey for mentors, the same question was reworded as how helpful

they had been in assisting their mentees. Of the 107 responses from mentors,

81% (n=86) indicated “very helpful” or “helpful” compared to 92% (n=75) of the

81 responses from mentees. Mentors (20%, n=21) were more likely to have a

neutral attitude, feel their support was “unhelpful” or “very unhelpful,”

compared to the mentees (7%, n=6) (Figure 4). Overall, the mentees showed a

great appreciation for the mentoring support they received; by contrast, the

mentors seemed to be modest when evaluating their own value in assisting their

mentees. The Fisher's Exact Test indicated a significant difference in

perceptions between the two groups (P

= .000).

Figure 4

Perceptions of

the helpfulness of mentorship.

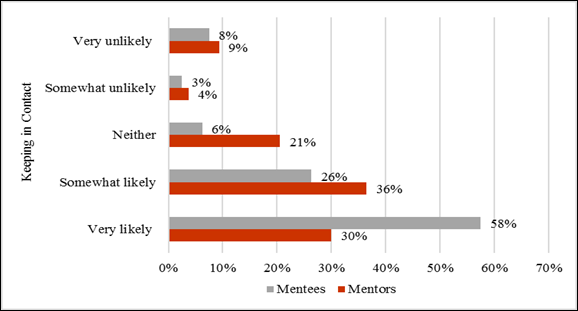

Likeliness of Keeping in Contact

As the

mentorship program ran for only two months, the ViMLoC Mentorship Committee

suggested that mentors and mentees could continue to connect with each other

even after the program ended if they would like. There were 107 responses from

mentors and 80 responses from mentees submitted regarding how likely they would

be to keep in contact with their mentoring partner. Of these responses, 58%

(n=46) of the mentees were “very likely” to keep the relationship, much higher

than that of the mentors (30%, n=32). Compared to the mentees, more mentors

indicated “somewhat likely,” “neither likely nor unlikely,” “somewhat

unlikely,” and “very unlikely” (Figure 5). Overall, it seemed that the mentees

were more interested in maintaining ties with their mentors, while the mentors

were not as enthusiastic to do the same. Their perceptions were found to be

significantly different based on the Fisher's Exact Test

(P = .002).

Figure 5

Perceptions of

the likeliness of keeping in contact.

In addition,

Fisher's Exact Tests were conducted separately for mentors and mentees to

examine the associations between the four items: ease of communication,

mentoring relationship, helpfulness of mentorship, and likeliness of keeping in

contact. Statistically highly significant relationships were identified for

both mentors and mentees between any two of the above four elements (all P = .000). These results suggested that

those who felt it was easier to communicate with their mentoring partner were

more likely to report a good relationship and to feel that the mentors were

helpful in assisting mentees. The pairs who established a better relationship

were more likely to feel that the mentoring support was helpful. Easier

communication, building a better relationship, and the feeling that the

mentoring support was more helpful were all associated with a greater

likelihood of keeping in contact beyond the mentorship program.

Skills for Building a Successful Mentoring Relationship

When mentees were asked, “What skills do you think

would be important to build a successful relationship with the mentor?,” there

were 64 open-ended responses, while 62 mentors responded to their equivalent

question that asked, “What skills do you think would be important to build a

successful relationship with the mentee?” As presented in Table 2, respondents

described 24 important skills or elements, some identifying multiple elements

within their response. For example, a mentor’s open-ended response was,

“Patience and listening skills to determine needs from mentee. Sometimes they

don’t know what they need to know until they feel comfortable enough to open

up.” It was coded as “patience,” “listening,” and “openness.” The most common

answer amongst both groups was communication (mentees n=28, mentors n=22).

Another common response that ranked highly amongst both groups was some form of

open communication, sometimes characterized as being able to open up to the

other (mentees n=13, mentors n=10). In addition, setting goals or expectations

was important for the mentoring relationship, ranking within the top five most

common responses for both groups, with mentees indicating 10 times and mentors

indicating eight times. The rest of the responses had more fluctuation between

mentors and mentees with regard to rating. Honesty rated high amongst mentees

(n=11), but only five mentors included it in their response, however, both

ranked within the top 10 common responses. Both flexibility or adaptability

with scheduling meetings (mentees n=5, mentors n=6) and asking questions

(mentees n=6, mentors n=5) ranked within the top 10 responses amongst both

groups. In some cases, what mentors perceived as important, such as being a

good listener (n=16), being empathetic (n=10), being knowledgeable (n=6), being

respectful (n=5), and being encouraging (n=5) did not rank high with mentees.

Likewise, mentees perceived being organized (n=9), being friendly (n=6), being

willing to learn (n=5), and the frequency of meetings (n=5) to be important

when mentors did not rank them as highly. Both groups barely mentioned the

category of interpersonal skills, but they specified elements of it separately

such as communication.

Previous Mentorship Experiences and Intentions to Mentor

Associations of Past Mentorship Experience with ViMLoC Mentorship Experience

Of the 81

mentors, 58% (n=47) had been mentored by an LIS professional, formally or

informally before joining the ViMLoC mentorship program. Over one third (35%,

n=28) engaged in a formal mentorship program for the first time. To examine if

their previous mentorship experience would relate with their ViMLoC mentorship

experience, Fisher's Exact Tests were run to check the associations between

having prior mentee experience and the following three variables, one at a

time: ease of communication, mentoring relationship, and helpfulness of

mentorship. As shown in Table 3, no significant relationship was identified.

Having formal mentor experience before did not make a significant difference in

their present experience either.

Of the 81

mentees, 77% (n=62) indicated it was their first time participating in a formal

mentorship program. Having prior formal mentorship experience was not

significantly related with their perceptions of ease of communication,

mentoring relationship, and helpfulness of mentorship in the ViMLoC mentorship

program.

Associations of ViMLoC Mentorship Experience with Intentions to Mentor in the Future

For mentors,

feeling helpful in assisting their mentees in the ViMLoC mentorship program was

not significantly associated with how likely they would be to mentor again in

the future (Table 3). For mentees, however, helpfulness from the ViMLoC

mentorship experience would significantly increase the likelihood of becoming a

mentor in the future (P = .002).

Table 2

Skills

Considered Important for Building a Successful Mentoring Relationship

|

Response |

What skills do

you think would be important to build a successful relationship with the

mentee? Mentors (n=62) |

What skills do

you think would be important to build a successful relationship with the

mentor? Mentees (n=64) |

|

Communication |

22 |

28 |

|

Listening |

16 |

4 |

|

Openness |

10 |

13 |

|

Empathetic |

10 |

2 |

|

Setting

expectations/goals |

8 |

10 |

|

Knowledgeable |

6 |

3 |

|

Flexibility of

scheduling |

6 |

5 |

|

Honesty |

5 |

11 |

|

Respectful |

5 |

4 |

|

Encouraging |

5 |

2 |

|

Asking

questions |

5 |

6 |

|

Open-minded |

4 |

3 |

|

Curious |

4 |

1 |

|

Experienced |

4 |

1 |

|

Interpersonal

skills |

3 |

3 |

|

Patience |

3 |

0 |

|

Friendly |

3 |

6 |

|

Timely

responses |

3 |

2 |

|

Frequency of

interactions |

3 |

5 |

|

Being

organized/prepared |

3 |

9 |

|

Trust |

2 |

3 |

|

Positive attitude |

2 |

4 |

|

Willingness to

learn |

2 |

5 |

|

Acting

professionally |

1 |

1 |

Table 3

Associations

between Past, Present Mentoring Experience, and Future Intentions to Mentor

|

Indicators |

Mentors |

Mentees |

|

Having Prior

Mentee Experience & Ease of Communication |

P = .681 |

N/A |

|

Having Mentee

Experience & Relationship |

P = .680 |

N/A |

|

Having Mentee

Experience & Helpfulness of Mentorship |

P = .451 |

N/A |

|

Having Formal

Mentorship Experience & Ease of Communication |

P = .463 |

P = .399 |

|

Having Formal Mentorship

Experience & Relationship |

P = .485 |

P = .577 |

|

Having Formal

Mentorship Experience & Helpfulness of Mentorship |

P = .427 |

P = .325 |

|

Helpfulness of

Mentorship & Going to Mentor Again in the Future |

P = .063 |

N/A |

|

Helpfulness of

Mentorship & Going to Mentor in the Future |

N/A |

P = .002* |

Note:

P values from Fisher's Exact Tests. * Significant at 0.01 level

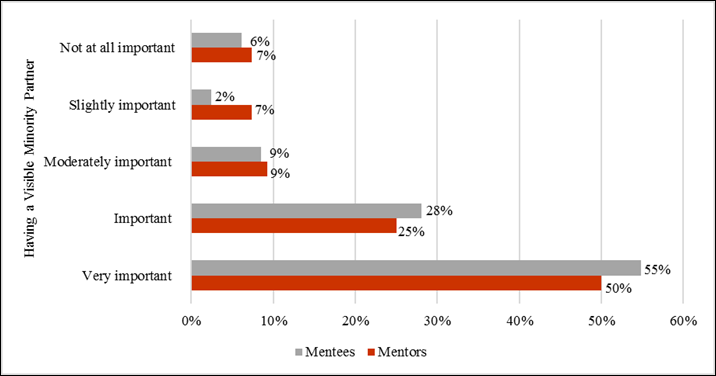

Importance of Having a Visible Minority Partner

When asked how

important it was to them that the mentoring partner was a visible minority, 75%

(n=81) of the 108 responses from mentors versus 83% (n=68) of the 82 responses

from mentees indicated “very important” or “important.” An equal share

indicated “moderately important,” both at 9%. More mentors 14% (n=16) than

mentees 8% (n=7) indicated “slightly important” or “not at all important”

(Figure 6). However, these differences in perspectives were not found to be

significant in the Fisher's Exact Test (p

= .633).

Figure 6

Perceptions of

the importance of having a visible minority partner.

Most Satisfying Aspects of the ViMLoC Mentorship Program

Both mentors

(n=51) and mentees (n=63) shared comments about what was the most satisfying

aspect of the ViMLoC mentorship program, many providing multiple aspects, which

provided great insights into the unique contributions that VM mentors could

make in supporting VM mentees. When coding the responses from the mentors, they

predominantly described the satisfaction of helping someone (n=25). When the

specific type of help was indicated, assistance with job hunting (n=4) and

advice about career development (n=4) were the most common, closely followed by

discussions about adjusting to the work culture (n=3) or helping the mentees

towards their goals (n=3). Many mentors remarked how they were able to connect

with someone new to expand their network (n=18). Another rewarding aspect that

was noted was the ability to share their experiences with others (n=10).

However, it was not just a one-way flow of experiences from mentors to mentees,

as seven mentors noted that they also learned something from the experience. For

example, one mentor mentioned that it was satisfying “[g]etting to understand

the perspectives of other new visible minority librarians. Hearing about their

accomplishments, as well as their challenges in the current library landscape

is eye opening.” Less frequently mentioned, but still notable was that the

mentors enjoyed providing the mentees with encouragement (n=6) and the ability

to give back (n=3), meaning they had also received similar professional support

and wanted to return the favor to someone else in the profession.

When mentees

shared what they thought was the most satisfying aspect, the ability to network

and make new connections with other library professionals was the most popular

response (n=32). The second most common response was related to the help they

received from the mentor (n=29). With most mentees being early on in their

library career, they needed more specific help with job hunting (n=8), career

guidance (n=4), and awareness of the work culture (n=4). Mentees appreciated

having their mentors share their experiences (n=19), with four saying that it

made them feel less alone and three that described how their mentors’

experiences were something they could role model. Touching upon many of these

aspects, one mentee disclosed that they “loved being able to connect and hear

from someone who was a visible minority in my desired profession. It can be

easy to feel a bit alone in this Caucasian-dominated field and I enjoyed

hearing my mentor share their experiences and how they navigate the workplace.”

Five mentees expressed their satisfaction with the encouragement they received

from their mentors and finally, three noted satisfaction with the mentorship

program itself and the comfort “[k]nowing that something like that exists.”

Within answers

from both mentors (n=12) and mentees (n=18) there were notable mentions about

being connected with someone who was also a visible minority and shared

experiences as visible minorities within the library profession. For example,

one mentor described that “[i]t’s a nice way to network with someone with

similar experiences and have conversations about being a visible minority

person in a workplace. I don’t see any other avenue where issues of being a

visible minority could be discussed in a professional setting.” Furthermore, a

mentee elaborated that they “have a Caucasian mentor through another program,

who I cannot talk to about anything related to race/identity as a visible

minority/immigrant. The most valuable part of the ViMLoC mentorship program was

the opportunity to connect with a fellow visible minority and ask questions

related to that.”

Discussion

Mentors and

mentees indicated that email and video chat were the most effective methods of

communication. This finding was in agreement with Binder et al. (2022) in which

mentors and mentees who interacted through web conferencing tended to report

higher satisfaction of their mentoring experiences, but against the result of

Jordan (2019) indicating that Skype or video chat was not as popular. The two

groups also reported the same top five areas of support activities. Likewise,

Harrington and Marshall (2014) found these five aspects were important

components of a mentoring relationship, which were categorized under career

guidance, psychosocial support, and role model. This could be associated with

the mentees’ career stages and their corresponding needs. More than half of the

mentees in the ViMLoC mentorship program were library school students. Their

questions were more frequently about librarians’ professional work and general

career preparation. In contrast, fewer questions were asked regarding promotion

and tenure, as well as research and scholarship activities that librarians put

on their professional development agenda years after entering the profession.

Moreover, the mentees did have concerns related to their VM identities. The

mentors who had similar racial backgrounds and experiences navigating the

Caucasian-dominated library landscape could provide comfort, encouragement, and

inspiration to the mentees.

The research

findings revealed that mentors and mentees significantly differed in how they

perceived the value of mentoring assistance. A higher proportion of mentees

found mentorship was helpful while a higher percentage of mentors felt their

assistance was unhelpful to mentees. The differences could be due to the fact

that 55% of the mentees in the mentorship program were library school students

and 26% were early career librarians. Without entering the library profession,

the student mentees typically needed guidance in career planning, job search,

and interview process. The mentors were all librarians who have gone through

the journey from library schools to the job market. They had the experience and

capacity to assist the mentees, thus making the mentees feel that it was

helpful. For the mentees who were early-career librarians, despite the

anonymity of the surveys, they might have been cautious about giving negative

feedback about someone in the profession, as they had not secured permanent

positions yet.

The mentors and

mentees also had significantly different perspectives regarding whether they

would like to keep in contact after the mentorship session ended. Mentees were

more likely to maintain the ties than mentors. They might have different

reasons for continuing the relationship beyond the program. Despite the

informal format, mentees could still benefit from the connection if the mentors

were willing to continue providing advice and support. As VMs are

underrepresented in the library world, the mentors would be invaluable

resources for the mentees to draw on in the future. For the mentors, some were

willing to connect again because they could learn and grow themselves while

supporting their mentees, or they found it personally rewarding to continue helping

mentees to succeed. Meanwhile, other commitments might hinder many mentors from

continuing the relationship. One respondent commented:

I had

a mentee with whom I had reviewed their resume and cover letter. I did not mind

doing this a few times during the mentorship. They asked me to review multiple

applications a few months after the mentorship ended and after our final wrap

up meeting. By this time, I had to let them know that I could only review their

application once more due to my other commitments.

The finding from

this research suggested that positive experiences from the ViMLoC mentorship

program would have a great impact on mentees’ intention to mentor in the

future. This could be explained by the “spillover effect” derived from the

benefits that the mentees received from the present mentoring relationship

(Ragins & Scandura, 1999). The act of being mentored creates more mentors,

which also seems to hold true according to the literature on VM mentorship.

When early-career minority librarians were surveyed, they described their

willingness to become a mentor in the future based on their positive

experiences as a mentee (Olivas & Ma, 2009). In practice, VM librarians in

higher education from Johnson’s (2016) dissertation benefited from their mentee

experience so that they actively sought out mentor opportunities “[i]n the

spirit of service to others” (p. 100). This is similar to Cho’s (2014) personal

experience; he described the help he received from VM mentors at his

institution when he was first starting his career and how he now participates

in mentorship programs for VM librarians as a rewarding way to give back.

Comparably, Boyd et al. (2017) found that residency programs could help develop

library leadership skills in VM librarians and in turn, they would likely go on

to recruit VMs to the profession and mentor early career VM librarians.

This research

has some implications for library associations and libraries seeking to support

VM library professionals within their own mentorship program. First, as the

findings indicated, the mentees who had positive experiences from the present

mentoring relationship were more likely to mentor others. Therefore, mentorship

program managers need to take a proactive role in improving the mentee

experience so that more mentees can become mentors to support others. This may

strengthen the pipeline for greater recruitment and retention among VM

librarians.

Second, the

research results showed that previous mentorship experience for both mentors

and mentees did not make significant differences in how they communicated and

built relationships in the present program. Hence, regardless of their

mentorship experience level, it is essential to give participants some guidance

at the start of the mentorship session to ensure that they all are on the same

page. Based on our open-ended question about the skills that would be important

to build a successful relationship with a mentee/mentor, future mentoring

programs for VM librarians should focus on supporting communication skills,

especially through encouraging people to open up. This is especially important

with VM groups within the profession since it can ease some of the negative

experiences from the workplace such as isolation and microaggressions.

Furthermore, they should ensure that mentors and mentees can clearly articulate

their goals or expectations and formulate good questions to ask each other to

gain a beneficial experience for the mentoring pairs.

Third, various

approaches could be taken to facilitate the mentoring relationship. The ViMLoC

Mentorship Committee provided guidelines to each participant. However, due to

the dynamic nature of each mentoring pair and their relationship, those

guidelines could not be used to resolve some issues that occurred. The

Committee’s timely intervention was necessary when issues came up. Examples of

issues included: communication being lost or delayed due to scheduling

difficulties from being in different time zones or being unable to fit the

meetings into respective schedules; mentees not showing much interest in

interacting, being uncommunicative, or not having clear expectations of the

program; mentors feeling it was hard to build a relationship within two months,

or being unable to answer questions outside their field of work. Although the

Committee could not intervene in all problems; they took various approaches to

help smooth things out when possible. For instance, they sent out two check-in

emails (one for all the mentees and the other one for all the mentors) after

the mentoring session was launched to make sure the pairs had connected with

each other and started a conversation. They helped mentees to find an

alternative mentor if the mentee did not find that the mentor was a good match.

When there was not a good fit from the pool of mentors, an informal mentor was

sought out and recommended to the mentee to connect with. When tensions

occurred between a mentoring pair and they reached out to the Committee, the

committee members held one-on-one meetings with individuals in an attempt to

gather more information, to understand their respective expectations and

concerns, and to facilitate the mentoring pair’s mutual understanding and

communication. It is important that “if a pairing is not compatible or causes

harm, then allow the pair to disengage with dignity” (Burke & Tumbleson,

2019, p. 12), and reassign the mentee to a mentor with a better fit whenever

possible (Goodsett & Walsh, 2015).

Limitations

First,

demographic information of the mentorship program participants, such as

ethnicity, geographic location, work experience, and the type of library they

work at, was gathered in the program application forms, however, such

information was not collected again in the surveys. As the surveys were

anonymous, there was no way of linking the survey respondents with their

applications. Hence, survey respondents’ mentorship experiences could not be

examined based on their demographic characteristics.

Second, as the

completion rate of the mentees was 15% lower than that of the mentors, it was

possible that some mentees who had negative experiences chose not to fill out

the surveys, and as a result, their experiences might not be reflected in this

research.

Third, this

research was based on the data gathered from the four mentoring sessions over

2018-2022. Except in 2018, the mentoring sessions occurred during the COVID-19

pandemic. This context could have affected the mentorship experiences of survey

respondents. For instance, communication became more difficult and might have

affected relationship building negatively due to the pandemic. Further research

efforts can seek to examine more sessions beyond the pandemic.

Conclusion

There are

numerous studies on mentorship within the library profession as a whole.

Research on mentorship for VM is increasing as mentoring support has been

perceived to be beneficial to VM mentees individually and to the

diversification of the library profession. This study contributed to the

literature through an empirical research method and comparative analyses of the

experiences between mentors and mentees in the ViMLoC mentorship program.

Statistically significant differences were identified between the two groups.

Mentoring support was perceived to be more helpful by the mentees than by the

mentors. The mentees were more likely to keep in contact with their mentors

beyond the mentorship program, while the mentors did not show as much interest.

A positive experience in the present mentoring relationship would increase the

intention of mentees to mentor others in the future, whereas the same effect

did not hold true for the mentors. On the other hand, some findings were shared

by both mentors and mentees, including the belief that effective communication

would facilitate a good mentoring relationship, which in turn, would lead to

positive outcomes and greater likelihood of keeping in contact beyond the

mentoring program. Mentor and mentee responses indicated they both agreed on

the most important areas of mentoring support and some essential skills for

building a successful mentoring relationship. In addition to contributing to

the librarianship literature, the practical implications of this research are profound

as there are very few mentorship programs characterized by VMs mentoring VMs.

The experiences shared in this research will be helpful to library associations

and libraries who are interested in operating a mentorship program for VM

library professionals.

Author Contributions

Yanli Li:

Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Quantitative

Analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review &

editing Valentina Ly: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology,

Qualitative Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing Xuemei

Li: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original

draft, Writing – review & editing

References

Abdullahi, I. (1992). Recruitment and mentoring of minority students. Journal of Education for Library and

Information Science, 33(4),

307-310. https://doi.org/10.2307/40323194

Adekoya, C. O. & Fasae, J. K. (2021). Mentorship

in librarianship: Meeting the needs, addressing the challenges. The Bottom Line, 34(1), 86-100. https://doi.org/10.1108/BL-09-2020-0063

Alabi, J. (2015). Racial microaggressions in academic libraries: Results

of a survey of minority and non-minority librarians. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(1), 47-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.10.008

Alston, J. K. (2017). Causes of satisfaction and dissatisfaction for

diversity resident librarians - A mixed methods study using Herzberg’s

motivation-hygiene theory [Doctoral dissertation, University of South

Carolina]. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4080/

Binder, A., O’Neill, B., & Willey, M. (2022). Meeting a need:

Piloting a mentoring program for history librarians. Library Leadership & Management, 36(2), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.5860/llm.v36i2.7524

Bonnette, A. E. (2004). Mentoring minority librarians up the career

ladder. Library Administration &

Management, 18(3), 134-139. https://doi.org/10.5860/llm.v36i2.7524

Boyd, A., Blue, Y., & Im, S. (2017). Evaluation of academic library

residency programs in the United States for librarians of colour. College & Research Libraries, 78(4), 472-511. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.78.4.472

Brown, J., Ferretti, J. A., Leung, S., & Méndez-Brady, M. (2018). We

here: Speaking our truth. Library Trends,

67(1), 163-181. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2018.0031

Bugg, K. (2016). The perceptions of people of colour in academic

libraries concerning the relationship between retention and advancement as

middle managers. Journal of Library

Administration, 56(4), 428-443. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2015.1105076

Burke, J. J., & Tumbleson, B. E. (2019). Mentoring in academic

libraries. Library Leadership &

Management, 33(4), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.5860/llm.v33i4.7348

Cho, A. (2014). Diversity pathways in librarianship: Some challenges

faced and lessons learned as a Canadian-born Chinese male librarian. In D. Lee

& M. Kumaran (Eds.), Aboriginal and

visible minority librarians: Oral histories from Canada (pp. 89-102).

Scarecrow.

Cooke, N. A., & Sánchez, J. O. (2019). Getting it on the record:

Faculty of colour in library and information science. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science, 60(3), 169-181. https://doi.org/10.3138/jelis.60.3.01

Espinal, I., Sutherland, T., & Roh, C. (2018). A

holistic approach for inclusive librarianship: Decentering whiteness in our

profession. Library Trends, 67(1), 147-162. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2018.0030

Farrell, B., Alabi, J., Whaley, P., & Jenda, C. (2017). Addressing

psychosocial factors with library mentoring. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 17(1), 51-69. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2017.0004

Ford, A. (2018, November 1). Underrepresented,

underemployed: In the library-job search, some face special barriers.

American Libraries Magazine. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2018/11/01/underrepresented-underemployed/

Garrison, J. (2020). Academic library residency programs and diversity. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 20(3), 405-409. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2020.0020

Gohr, M. (2017). Ethnic and racial diversity in libraries: How white

allies can support arguments for decolonization. Journal of Radical Librarianship, 3, 42-58. https://journal.radicallibrarianship.org/index.php/journal/article/view/5

Goodsett, M., & Walsh, A. (2015). Building a strong foundation:

Mentoring programs for novice tenure-track librarians in academic libraries. College & Research Libraries, 76(7),

914-933. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.7.914

Government of Canada. (2021). Employment

equity act. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/E-5.401/page-1.html#h-215195

Harper, L. M. (2020). Recruitment and retention strategies of LIS

students and professionals from underrepresented groups in the United States. Library Management, 41(2/3), 67-77. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-07-2019-0044

Harrington, M. R., & Marshall, E. (2014). Analyses of mentoring

expectations, activities, and support in Canadian academic libraries. College & Research Libraries, 75(6),

763-790. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.75.6.763

Hathcock, A. (2015, October 7). White librarianship in blackface:

Diversity initiatives in LIS. In the

Library with the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2015/lis-diversity/

Hernandez, M. N. (1994). Mentoring, networking and supervision:

Parallelogram, vortex, or merging point? In D. A. Curry, S. G. Blandey & S.

M. Martin (Eds.) Racial and ethnic

diversity in academic libraries: Multicultural issues (pp. 15-22). The

Haworth Press.

Hoffman, S. (2014). Mentoring diverse leaders in academic libraries. In

B. L. Eden & J. C. Fagan (Eds.), Leadership

in academic libraries today: Connecting theory to practice (pp. 77-91).

Rowman & Littlefield.

Hussey, L. K. (2006). Why librarianship? An exploration of the

motivations of ethnic minorities to choose library and information science as a

career. In D. E. Williams, J. M. Nyce & J. G. Williams (Eds.) Advances in Library Administration and

Organization (pp. 153-217). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0732-0671(2009)0000028007

Ibraheem, A. I., & Devine, C. (2013). A survey of the experiences of

African librarians in American academic libraries. College & Research Libraries, 74(3), 288-306. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl-292

Johnson, P. (2007). Retaining and advancing librarians of colour. College & Research Libraries, 68(5), 405-417. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.68.5.405

Johnson, K. (2016). Minority

librarians in higher education: A critical race theory analysis [Doctoral

dissertation, Marshall University]. https://mds.marshall.edu/etd/1019

Jordan, A. (2019). An examination of formal mentoring relationships in

librarianship. The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 45(6), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.102068

Kandiuk, M. (2014). Promoting racial and ethnic diversity among Canadian

academic librarians. College &

Research Libraries, 75(4),

492-556. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.75.4.492

Kendrick, K. D., & Damasco, I. T. (2019). Low morale in ethnic and

racial minority academic librarians: An experiential study. Library Trends, 68(2), 174-212. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2019.0036

Kim H. Y. (2017). Statistical notes for clinical researchers:

Chi-squared test and Fisher's Exact Test. Restorative

dentistry & endodontics, 42(2),

152-155. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2017.42.2.152

Kumaran, M. (2013). Visible minority librarians of Canada at Ontario

Library Association super conference, 2013. Partnership:

The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 8(2), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v8i2.2888

Kumaran, M., & Cai, H. (2015). Identifying the visible minority

librarians in Canada: A national survey. Evidence

based library and information practice, 10(2), 108-126. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8ZC88

Lee, E., & Morfitt, P. (2020). Imposter syndrome, women in technical

services, and minority librarians: The shared experience of two librarians of

colour. Technical Services Quarterly,

37(2), 136-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317131.2020.1728125

Majekodunmi, N. (2013). Diversity in libraries: The case for the Visible

Minority Librarians of Canada (ViMLoC) Network. Feliciter, 59(1), 31-33. https://yorkspace.library.yorku.ca/xmlui/handle/10315/35701

McCook, K., & Lippincott, K. (1997). Planning for a diverse workforce in library and information science

professions. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED402948.pdf

Montiel-Overall, P., & Littletree, S. (2010). Knowledge river: A

case study of a library and information science program focusing on Latino and

Native American perspectives. Library

Trends, 59 (1), 67-87. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/4827147.pdf

Moore, A. A., Miller, M. J., Pitchford, V. J., & Hwey Jeng, L.

(2008). Mentoring in the millennium: New views, climate and actions. New Library World, 109(1/2), 75-86. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074800810846029

Olivas, A. P. (2014). Understanding

underrepresented minority academic librarians’ motivation to lead in higher

education [Doctoral dissertation, University of California, San Diego]. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5gq790c0

Olivas, A., & Ma, R. (2009). Increasing

retention rates in minority librarians through mentoring. The Electronic Journal of Academic and Special Librarianship, 10(3),

1-9. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1119&context=ejasljournal

Ragins, B. R., & Scandura, T. A. (1999). Burden or

blessing? Expected costs and benefits of being a mentor. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 20(4), 493-509. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3100386

Ruan,

L., & Liu, W. (2017). The Role of Chinese American librarians in library

and information science diversity. International Journal of

Librarianship, 2(2), 18-36. https://doi.org/10.23974/ijol.2017.vol2.2.39

Thornton, J. K. (2001). African American female librarians. Journal of Library Administration, 33(1–2), 141-164. https://doi.org/10.1300/J111v33n01_10

VanScoy, A. & Bright, K. (2017). Including the voices of librarians

of colour in reference and information services research. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 57(2), 104-114. https://journals.ala.org/index.php/rusq/article/view/6527

Zhang, S. L., Deyoe, N., & Matveyeva, S. J. (2007). From scratch:

Developing an effective mentoring program. Chinese

Librarianship: an International Electronic Journal, 24, 1-16. http://www.white-clouds.com/iclc/cliej/cl24ZDM.pdf

Appendix

A

Survey Questionnaire

2022 for Mentors (with One Mentee)

Q1 Thank you for

participating in this survey! We would like to hear your feedback on the 2022

ViMLoC Mentorship Program so that we can continue to improve it. Please look

over the Informed Consent Letter before proceeding.

o I

have read and understand the above information. I agree to participate in this

study.

o I

have read and understand the above information. I do not want to participate in

this study.

Q2 How did you hear about

the ViMLoC Mentorship Program? (Please select all that apply)

o

ViMLoC group

o

School

o

Conference

o

Colleague

o

Social media (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc.)

o

Friend

o

Contacted by the ViMLoC Mentorship Committee

o

Other

Q3 What are your reasons for participating as

a mentor in the ViMLoC Mentorship Program? (Please select all that apply)

o Professional development

o Promotion

o Meeting requirements for tenure

o Passion for helping others

o Networking

o Sharing experience

o Other

Communication:

How many times have you used the methods

below to communicate with your mentee:

Q4 E-mail (you sent to the mentee): 0, 1, 2 …9, 10 and above

Q5 Online chat/instant messenger: 0, 1, 2 …9,

10 and above

Q6 Skype or video chat: 0, 1, 2 …9, 10 and

above

Q7 In person: 0, 1, 2 …9, 10 and above

Q8 Telephone: 0, 1, 2 …9, 10 and above

Q9 What was the most effective method of

communication?

o Email

o Online chat/instant messenger

o Skype or video chat

o In person

o Telephone

o Other (please specify) ____________

Interactions:

Q10 In your early

contacts with your mentee, did they discuss their mentorship program

expectations with you?

o Yes

o No

Q11 How important was it to you that the

mentee was a visible minority?

o Very important

o Important

o Moderately important

o Slightly important

o Not at all important

Q12 Did you discuss any experiences about

being a visible minority in the profession with your mentee?

o Yes

o No

Q13 How easy was communication with your

mentee?

o Very easy

o Easy

o Moderately easy

o Difficult

o Very difficult

Q14 How would you describe your relationship

with your mentee?

o Very good

o Good

o Fair

o Poor

o Very poor

Q15 How likely are you to keep in contact with

your mentee after the program ends?

o Very likely

o Somewhat likely

o Neither likely nor

unlikely

o Somewhat unlikely

o Very unlikely

Q16 How helpful do you think you were in

assisting the mentee?

o Very helpful

o Helpful

o Neither helpful nor

unhelpful

o Unhelpful

o Very unhelpful

Q17 What aspects did you help your mentee

with? (check all that apply)

o provide encouragement

o provide career counseling

o help with job seeking skills (cover letter,

resume, interview, etc.)

o assist with networking

o help with setting mentee's professional goals

o share own professional experience with the

mentee

o share experience about the day to day work

life

o help with orientation to library culture and

workplace expectations

o advise on how to adapt in an organization as

a visible minority

o address the mentee's professional concerns

o provide knowledge of a discipline or subject

area

o assist with research and scholarship (grant

writing, research methods, etc.)

o assist with promotion and tenure (preparation

of materials, procedure, criteria, etc.)

o share experience or improve skills in

instruction

o share experience or improve skills in

collection management

o share experience or improve skills in

reference services

o share experience or improve skills in

leadership

o share experience or improve skills in

community involvement or outreach

o share experience or improve skills in

technology-related library work

o Other

Mentorship Experience:

Q18 In the past, were you

ever mentored by an LIS professional, formally or informally?

o Yes

o No

Q19 Is this your first

experience as a mentor through a formal mentorship program?

o Yes

o No

Q20 Based on this experience, how likely would

you be to mentor again in the future?

o Very likely

o Somewhat likely

o Neither likely nor

unlikely

o Somewhat unlikely

o Very unlikely

Q21 What skills do you think would be

important to build a successful relationship with the mentee?

___________________________________

ViMLoC Mentorship Program

Assessment:

Q22 What has been the

most satisfying aspect about the ViMLoC Mentorship Program?

________________________________________________________________

Q23 What has been the

least satisfying aspect about the ViMLoC Mentorship Program?

________________________________________________________________

Q24 How did you feel

about the level of interaction commitment required (two interactions a month)

for the ViMLoC Mentorship Program?

o Too much

o About right

o Too little

Q25 What would you suggest to improve the

ViMLoC Mentorship Program?________

Appendix B

Survey Questionnaire

2022 for Mentees

Q1 Thank you for

participating in this survey! We would like to hear your feedback on the 2022

ViMLoC Mentorship Program so that we can continue to improve it. Please look

over the Informed Consent Letter before proceeding.

o I have read and understand

the above information. I agree to participate in this study.

o I have read and

understand the above information. I do not want to participate in this study.

Q2 How did you hear about

the ViMLoC Mentorship Program? (Please select all that apply)

o

ViMLoC group

o

School

o

Conference

o

Colleague

o

Social media (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc.)

o

Friend

o

Contacted by the ViMLoC Mentorship Committee

o

Other

Q3 What are your reasons

for participating as a mentee in the ViMLoC Mentorship Program? (Please select

all that apply)

o Knowing more about the

profession

o Seeking guidance in

career direction

o Moving up in your

career

o Seeking advice on how

to transfer skills obtained from your home country

o Learning about the

skills and qualifications needed for a librarian-related job

o Networking

o Learning about how to

adapt in an organization as a visible minority

o Other

Communication:

How many times have you used the methods below

to communicate with your mentor:

Q4 E-mail (you sent to the mentor): 0, 1, 2 …9,

10 and above

Q5 Online chat/instant

messenger: 0, 1, 2 …9, 10 and above

Q6 Skype or video chat: 0, 1, 2 …9, 10 and

above

Q7 In person: 0, 1, 2 …9,

10 and above

Q8 Telephone: 0, 1, 2 …9,

10 and above

Q9 What was the most

effective method of communication?

o Email

o Online chat/instant

messenger

o Skype or video chat

o In person

o Telephone