Research Article

Swimming Upstream in the

Academic Library: Exploring Faculty Needs for Library Streaming Media

Collections

Elsa Loftis

Humanities and Acquisitions

Librarian, Assistant Professor

Portland State University

Portland, Oregon, United States

of America

Email: eloftis@pdx.edu

Carly Lamphere

Science Librarian

Reed College

Portland, Oregon, United States

of America

Email: lampherec@reed.edu

Received: 2 Feb. 2023 Accepted: 23 Aug. 2023

![]() 2023 Loftis and Lamphere. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2023 Loftis and Lamphere. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30317

Abstract

Objective

- To compare Portland State University’s (PSU) local

experience of using streaming media to national and international trends identified

in a large qualitative study by Ithaka S+R. This comparison will help

librarians better understand if the PSU Library is meeting the needs of faculty

with its streaming media collection through a series of faculty interviews.

Methods

and Intervention - Two librarians from PSU participated in a large,

collaborative, two-part study conducted by Ithaka S+R in 2022, with 23 other

academic institutions in the United States, Canada, and Germany As part of this

study, the authors conducted a series of interviews with faculty from PSU’s

Social Work and Film Studies departments to gather qualitative data about their

use, expectations, and priorities relating to streaming media in their

teaching. Ithaka S+R provided guided interview questions, and librarians at PSU

conducted interviews with departmental faculty. Local interview responses were

compared to the interviews from the other 23 institutions.

Results

- PSU Library had a higher rate of faculty

satisfaction than in the larger survey. Discussions raised concerns around

accessibility of content, which was novel to PSU, and did not meaningfully

emerge in the broader study. Local findings did line up with broader trends in

the form of concerns about cost, discoverability, and lack of diverse

content.

Conclusions - The data collected by Ithaka S+R’s survey, which was the first

part of their two-part study, is useful as it highlights the trends and

attitudes of the greater academic library community. However, the second

portion of the study’s guided interviews with campus faculty reinforced the

importance of accessibility, the Library’s provision of resources, and the

relationships between subject liaisons and departmental instructors. It

emphasized that Portland State University’s Library has built a good foundation

with faculty related to this area but has not been able to provide for every

streaming instructional need. Reasons for this include limited acquisitions

budgets, constraints of staff time, and market factors.

Introduction

In 2021 and 2022, two librarians from Portland State’s University’s Millar

Library participated in a study facilitated by Ithaka S+R “Making Streaming

Media Sustainable for Academic Libraries” to identify emerging streaming media

trends and needs on academic campuses. Portland State University (PSU) is a

public urban university in Oregon, with approximately 23,000 enrolled students,

and is an R2 Doctoral University with 201 degree programs. PSU employs 1,690

research and instructional faculty (Portland State University, 2022). Ithaka

S+R is a not-for-profit organization dedicated to helping academic and cultural

communities navigate issues in higher education. Their research projects are

designed to “generate action-oriented research for institutional

decision-making and act as a hub to promote and guide collaboration across the

communities we serve” (Ithaka S+R, 2022).

Ithaka S+R’s

project consisted of two phases focused on making streaming media more

sustainable for academic libraries. The first phase was a U.S. and Canada-wide

survey sent to 1,493 individuals by invitation from Ithaka S+R. This survey

assessed and evaluated the competitive landscape of streaming media licensing

for libraries. The results of that survey were shared with the investigators

from the 24 participating libraries at the cohort-wide meeting in Fall 2021,

and then published widely (Cooper et al., 2022).

Phase two of the

research project was a series of interviews conducted by librarians from the 24

college campuses. This article focuses on interview findings from Portland

State University’s faculty. Two investigators from PSU’s Millar Library

conducted 10 interviews with faculty in the Film Studies and Social Work

departments in the Winter/Spring of 2022.

Ithaka S+R’s collaborative research project was an opportunity to survey

faculty at PSU about streaming media preferences in instruction to better

understand how the Library was meeting service and support needs. In turn, PSU

also contributed to developing strategies for libraries as they continue to

navigate the complex landscape of streaming media in higher education. Broadly,

the survey reinforced the preliminary assumption that streaming media is

increasingly important in academic library collections, both before and during

the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey feedback also revealed how faculty across

different institutions incorporated streaming media into instruction. Reviewing

PSU faculty’s interviews provided the Library with information regarding how to

tailor outreach and other services to better assist faculty and students

accessing streaming media in their courses.

PSU’s Library was awarded the ReImagine PSU Grant to participate in the

Ithaka S+R project. The grant emerged as an effort to transform campus services

to better serve students during a time of pandemic transition. Streaming

services in instruction and access during the pandemic continues to be an

equity issue, as many students do not have reliable high-speed internet or the

devices required to access content in this way. Learning more about the needs

of our faculty and students will inform the Library on how to better meet those

challenges.

Literature Review

Streaming media usage has risen on campuses nationwide, as documented in

recent library literature and demonstrated on PSU’s campus (Wang & Loftis,

2020). More recently, according to a survey by Tanasse (2021), 96.7% of

responding libraries offer streaming media. Academic libraries grew accustomed

to incorporating streaming films into their selection, acquisition, cataloging,

and budgetary workflows for several years, albeit with variations in a climate

of consistent change.

During the public health crisis of COVID-19, many libraries restricted

access to physical collections and universities rapidly shifted toward remote

learning where possible (Grove, 2021). This exacerbated the already growing

demand for the streaming format that outpaced library acquisitions budgets

(Lear, 2022). Regardless of whether libraries can afford continued subscription

and license renewals indefinitely, it became clear that a “preference” for

streaming media has evolved into “necessity,” based on trends in media

consumption (Lear, 2022), as well as instructors’ pedagogical aims and

instructional realities. In addition to the growth of online courses, reasons

for the new dominance of streaming include use of film to accommodate multiple

learning styles, instructors adopting “flipped classroom models,” and physical

media players becoming increasingly obsolete (Adams & Holland, 2017).

In addition to budgetary hardships and workflow complications for

libraries, students experience a variety of difficulties with accessing and

utilizing streaming media. COVID-19 further underscored the problems of the

digital divide in the United States, which is particularly significant for

rural residents who struggle with readily available speedy internet service

that can keep pace with these resources (Lai & Widmar, 2020). Other

variables for student access depend upon video quality, presence or absence of

subtitles, closed captions, or audio description (Peacock & Vecchione,

2019).

In addition to

addressing the digital divide exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, librarians

and faculty members recognize the importance of developing and expanding their

accessibility standards for streaming media collections. Some libraries have

begun to adopt policies of Universal Design for Learning to increase digital

equity and inclusion in collection access. This ranges from lending Wi-Fi

hotspots, expanding library remote services, and most importantly, purchasing

library materials that are accessible for all users (Frank et al., 2021). While

there are outlined recommendations for these practices from the National

Digital Inclusion Alliance (NDIA), there are few recommendations for streaming

media specifically beyond encouraging libraries to ensure streaming titles are

closed captioned and offer transcripts. A last recommendation is relying on

campus/institution accessibility services to help caption and make other media

accessible when licensed content does not include closed captions or transcripts

(Frank et al., 2021).

It can be

challenging to procure films that have accessibility features if they are not

available on the market. The authors

otherwise found a paucity of studies regarding specific streaming accessibility

best practices, a gap which should be further explored in library literature.

In addition to

exploring more specific accessibility needs for streaming media, libraries also

noted the importance of surveying their faculty and students when making

streaming media collection decisions. There have been several focus group

research studies in recent years to assess and inform librarians making

streaming media collection decisions such as developing collection decision

workflows (VanUllen et al., 2018) and usability preferences (Hill &

Ingram-Monteiro, 2021). Once assessed, libraries strive to make collection

decisions that inform their unique user populations and preferences for

streaming media and share these focus group/survey models for future research.

In a study by Beisler et al. (2019) it is evident that students express a need

for “streaming content that was credible and appropriate for academic

purposes,” while faculty generally are concerned with content being

discoverable, and reliable. While strides towards best practices have been made

for accessibility, there are still gaps in universal best practices to collect

this format. In the meantime, libraries must create boutique policies and

approaches to try to satisfy the needs of their unique user populations.

In 2021, Ithaka S+R launched a survey of academic libraries and released

its report in June of 2022, which reinforced the importance of streaming media

in library collections. A total of 96% of librarians surveyed said the “impact

on instruction is the number one factor shaping library decision making in

purchasing and renewing streaming licenses” above even cost considerations.

Another notable finding from the survey is that academic institutions were

already heading this direction before the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the

immediate need for streaming media (Cooper et al., 2022). The study goes on to

reveal that nearly half of the librarians surveyed (42%) strongly agree that

demand for streaming media has increased since March of 2020, yet only 23% of

librarians at doctoral institutions strongly agree that their library’s

strategy around streaming media licensing has changed (2022). In summary, while

costs and demand rise, the collective profession has not made a meaningful

response in terms of reimagining how we select and acquire this format.

Methodology

Prior to conducting the interviews with faculty, both investigators

participated in two training sessions with staff from Ithaka S+R and the other

project participants. The training consisted of sharing the interview materials

such as the script (Appendix A) with questions and tips on how to conduct a

research interview, and built-in time to practice with other participants. The

investigators submitted paperwork for IRB approval for participation in the

project and were granted Human Research Protection Program (HRPP) Exemption

prior to the faculty interviews.

The

investigators chose to select faculty from Film Studies and Social Work

departments due to their consistent need for streaming services in their

instruction. A total of 10 faculty participants were recruited, five from each

department. An initial call for volunteers was sent to the departments via

email, and the librarians selected faculty that they knew were frequent

requestors for media content. Of the faculty approached, there was a 90%

acceptance rate to participate in the interviews. Of these, 50% had indefinite

tenure at the institution, while the remaining participants were either at the

rank of assistant professor, adjunct faculty, or at the rank of instructor. The

anonymity of the conversations enabled the faculty to be candid in their

remarks, and the researchers believe that this is why adjunct faculty did not

appreciably respond much differently than full professors, for example. Future

studies should include other disciplines, but the librarians felt that Social

Work and Film Studies were excellent choices due to their high use of streaming

content, and their similarities and differences incorporating streaming media

into their instruction.

Each interview

was conducted and recorded over Zoom with auto transcription enabled to provide

a starting point for packaging the final transcript sent to Ithaka S+R in the

Spring of 2022 for analysis and inclusion in their final report. Investigators

reviewed the auto-generated transcript to make any necessary corrections, and

de-identified the faculty to ensure anonymity in the broader study. Researchers

at Ithaka S+R did the final coding and analysis as they compiled interviews

from all 24 participating academic institutions (MacDougall & Ruediger,

2023).

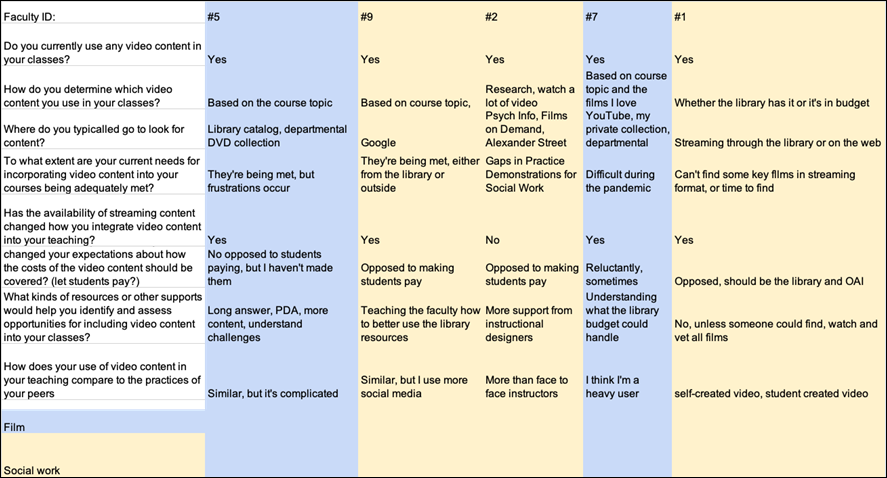

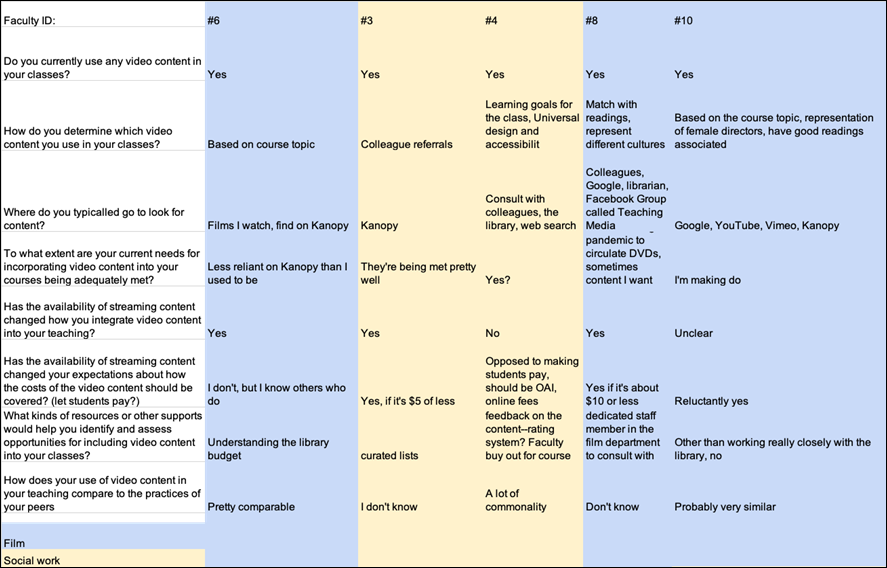

PSU’s interviews were reviewed by the librarians and put into a spreadsheet

for general comparative analysis (Appendix B). This provided faculty reactions

at a glance, which enabled easier comparison between PSU’s experience and the

findings from the larger collected survey, which included 244 total interviews

from faculty in a wide range of disciplines.

Results

The interviews

illustrate how PSU’s faculty view and utilize streaming media and library

services in their teaching practice. Faculty were able to express their

frustration and satisfaction with the current model of streaming services at

Millar Library. Some feedback varied between disciplines, and yet there were

also commonalities across both Social Work and Film Departments.

Social Work

faculty utilized streaming media in their instruction as supplemental material,

a practical demonstration tool for concepts introduced in their courses, and as

instruction materials for clinical practice courses. Film faculty utilize

streaming content as their base text for analysis and demonstrate properly

executed technical production skills. Faculty in both disciplines taught in

different environments: online, hybrid, and in person.

The themes from

the Portland State University interviews are discussed below and are separated

into the following sections: Accessibility Challenges, Discovery, and Cost

Containment. The valuable insight they offered also underscores the importance

of faculty/librarian relationships, which was also spoken about in many

interviews.

Accessibility Challenges

One of the most

surprising insights offered during the faculty interviews was a heightened

awareness of student accessibility. This concern was more pronounced among the

PSU faculty in comparison with the broader national study from other

participating institutions, where these concerns were not meaningfully

explored. Accessibility is often conflated with discoverability and whether a

film ‘can be accessed’, not specific concerns around usability. While generally

satisfied with captioning services, faculty are interested in reimagining the

current model of captioning services within the Disability Resources Center

(DRC) department at PSU. Faculty want captioning as a basic feature of

streaming media content and not only for students who have formal disability

accommodations. Many students who do not formally meet the requirements for

submitting accessibility requests still benefit from captions due to a variety

of different learning styles. As one

faculty member expressed: “I think it addresses a lot of learning styles when

you have captioning and it shouldn’t be where we have to have a person that has

to get an accommodation that you know, maybe 50% of a class would benefit from,

but they don’t have accommodations. It's just that it works better to have the

audio and the captioning at the same time.” Faculty expressed how using

streaming services helped to support different learning styles and increased

focus on accessibility challenges would naturally follow suit. The Library has

built this concern into all of its purchasing, but gaps occur when faculty use

streaming media that is not licensed by the Library.

Some faculty caption media themselves because they cannot rely on the auto

captioning offered by some platforms. This includes media clips created by

faculty members themselves to support instruction: One faculty member stated:

“Sometimes it’ll take me like 45 minutes to make two small clips…so you finally

have these two clips. It’s like 10 minutes of content you share and then you

find out ‘oh this doesn’t need to be captioned because it’s a foreign film it’s

subtitled’ and I’m like ‘Oh, but it's not like captioned-captioned.’” It is a

time-intensive endeavor for faculty members already stretched thin with

teaching and research.

Due to the

number of streaming platforms, it is common to encounter a variety of delivery

options. A film might be viewed on a vendor platform, emailed in the form of an

mp4 file to host on the Library’s local platform, or mailed as a DVD that staff

are to digitize. This can lead to complications in workflow for Acquisitions

and Cataloging staff, but the important disparity is the lack of uniformity in

accessibility options.

Some vendors

consistently offer closed captioning and transcripts with their films. Some

vendors supply the Library with different versions of the film with audio

descriptions for visually impaired viewers, but this is rare. Non-English

dialog is sometimes subtitled, but not always, and the variety of available

languages of subtitle options is limited. The Library is often limited by what

is available since any given film is commonly only available for institutional

purchase by one vendor. As noted by Beisler et al. (2019), captions are a great

pedagogical value to faculty for these reasons, as well as supplementing poor

audio quality, and for students who might be viewing films in loud

environments.

Ultimately, when discussing whether a streaming film

is ‘accessible’ the conversation is normally about whether closed captions are

provided. This overlooks audio description services that assist learners with

visual impairments, which is a rarity on the market, and therefore not often library

provided. Another aspect of accessibility is whether transcripts are provided,

which again varies by vendor. Also of concern is the relative accessibility of

the hosting site where viewers may be searching for and accessing films,

libraries should ensure that they are user friendly, able to be read by a

screen reader, and so forth.

The fact that the Library is sometimes pressed to

refer students and researchers to outside streaming services (commercial, open

web) means that it is not always able to assess or control the accessibility

standards of the content students consume. The Library only controls its own

provisions, in compliance with the University’s Standard for Accessible Digital

Procurement, (Portland State University, 2023), ensuring acceptable

accessibility levels. Ultimately, the Library’s ability to provide quality resources

that are accessible and desirable to faculty and students hinges on whether our

community is indeed utilizing Library resources. When instructors and students

are compelled to use sources not provided by the Library, important

considerations such as these can potentially be unaddressed.

Discovery

PSU faculty’s interview responses echoed that of

faculty at the other 23 institutions represented in the Ithaka S+R study.

Issues around discoverability were raised, as busy faculty often use the open

web to find films before going to the Library catalog or databases. The

findings from Ithaka suggest that YouTube is the most common source of

streaming films utilized by faculty. PSU’s faculty disputed this to some

extent, with 50% of surveyed faculty naming YouTube or Google specifically when

asked where they search for content, whereas 80% cited the Library’s catalog or

subscription databases.

Many faculty in

the national study described library catalogs and databases as “confusing”,

“unreliable”, and “impossible to navigate”. The Ithaka report conveys “Personal

connections with librarians were fundamental to faculty satisfaction with

library resources” (MacDougall & Ruediger, 2023). This was also the case

with PSU’s faculty, who consulted a combination of subject librarian, the

catalog, and alternative discovery routes to locate resources and help

facilitate access for their students. Throughout all interviews, the subject

librarian played a crucial role in helping navigate streaming media access and

discovery. On PSU’s campus, a study by Wang and Loftis (2020) was conducted to

determine how streaming media was discovered, and the results reinforce the

validity of that perception; faculty use the catalog, but also search other

vendor platforms, finding those discovery systems more intuitive. In support of

this, Beisler et al. (2019), state in their study that “Faculty expressed very

clearly that having content available is not enough; streaming video must be

easy to find and use and be reliable, or the content will not be used”.

Cost Containment

Ithaka’s study

revealed that keeping costs low for students is a major priority for

instructors. Local interviews also reinforced this, with 60% of interviewees

responding that students should not have to pay additional rental fees or

individual subscriptions for streaming films in courses. 40% of the faculty

stated that they would reluctantly require students to pay for content, but

none were pleased by the prospect. The interviewees who suggested that they

would require students to pay out of pocket for film rentals indicated a

ceiling of around $5 to $10 as the limit they would expect to burden students.

Keeping costs low for the Library and individual students was understood as a

necessity. This is reinforced in Dotson and Olivera’s 2020 case study about the

affordability of course materials in general, and how faculty often try to

mitigate students’ burdensome costs by increasingly using non-textual resources

such as streaming media and Open Educational Resources.

Streaming media

budgets have been a consistent concern on PSU’s campus for several years as

rising demand quickly outpaced the ability to contain costs. Strategies ranged

from using Patron Driven Acquisitions (PDA) models, exploring options via a

consortia subscription, and requesting individual titles from filmmakers, for

example. Despite the various methods of streaming acquisition types available,

a unified, cost-conscious strategy for the Library is strongly desired and

would benefit students and faculty.

Local Needs and Strategies

Information about streaming media appears in Portland State University Library General Collection Guidebook,

which acts as the Library’s outward-facing collection development policy (Emery

& Loftis, 2020). The Acquisitions Librarian created a companion Library

Guide dedicated to using films in courses, with information about the Library’s

decision-making process in licensing among other topics such as copyright,

public performance rights, and other relevant information. It also outlines

current criteria for purchasing single streaming licenses.

The interviews revealed that faculty have questions about how streaming

media is paid for and understand that it is expensive to supply and sustain.

Funding is not always the key issue, however. In the case of some feature

films, historical films, and foreign language content, institutional licensing

is not always available to libraries, and what is available in collections that

the Library subscribes to is not always satisfactory. The Library purchases

educational streaming licenses for popular feature films when affordable and

available. However, some content is simply not possible to license. These

difficulties are captured in an article by Lear (2022 p. 7) which discusses

barriers in filling streaming requests: “because vendors did not have streaming

rights in order to provide a license, or the distributor of the video did not

provide institutional streaming licenses. And, of course, requests from

streaming services such as Netflix and Hulu had a 0.0% success rate”. Similar

frustrations are felt in the PSU Library, where barriers such as these are

encountered with requested titles, with a similarly dismal success rate for

television series. In summary, there are varying levels of availability

depending on the titles being sought.

Conclusion

The results of the local faculty interviews were

analogous to key findings in the broader survey, notably: how streaming is

increasingly being used in instruction, keeping costs down for students as a

high priority, and that this media is being accessed both from within the

library and on commercial platforms in a patchwork.

That PSU faculty were aware of and concerned about

accessibility issues puts them ahead of the national trend in considering these

issues as central. The Library will play a role in advocacy in this area as we

demand improvements from our vendors in this realm.

Portland State University both reinforced and slightly

diverged from the collected findings in that Millar Library has generated

positive feedback in its ability to communicate and liaise with departmental

faculty. The broader survey likewise found that faculty were happy with

librarians and library services, however they indicated some general

dissatisfaction with library subscriptions and ability to deliver content. The

faculty answered a question that is crucial to the Library, which is “to what

extent are your current needs for incorporating video content in your courses

being adequately met?” Each PSU interviewee answered that, to some degree, they

felt well-supported. They each identified some frustrations, certainly, mostly

due to availability of certain titles, and the ephemeral nature of many

licenses, but it was largely positive and indicated goodwill towards the

library staff and the Library in general.

In the interviews, faculty were asked “what kinds of

resources or other support would help you identify and assess opportunities for

including video content in your classes?” The answers to this varied again by

department. Film studies faculty, nearly unanimously, answered that they would

like to know more about the Library budget, and what it could specifically

support. Social Work faculty, on the other hand, were far more interested in

learning about the Library’s existing resources and how best to discover and

utilize them. Faculty from Social Work suggested workshops for faculty to learn where best to find resources, and

they asked for more support from instructional designers with experience in

online learning. Social Work faculty also discussed the locally

created content that they or their students produced, either with

lecture-capture or social media clips, and wondered how those types of

streaming items could be housed and disseminated.

Ultimately, Portland State University’s Library built a

good foundation with faculty related to its provision of streaming media, but

more outreach can be done to offer support. Some factors are simply out of the

Library’s control, such as limited acquisitions budgets, constraints of staff

time, and market factors that render some content difficult to find and

license.

Streaming media is ubiquitous on Portland State

University’s campus just as it is on campuses across the globe. Libraries must

understand their faculty’s use, priorities, and barriers to making effective use

of this technology. As a trusted provider of streaming media to faculty and

students, a library ensures its relevance and stays true to its mission. If

faculty are not adequately provided for in this area, they are obliged to seek

content elsewhere, and this throws into question the quality, cost, copyright

compliance, and accessibility of the materials they use in class.

Author Contributions

Elsa Loftis and Carly Lamphere were equally

responsible for Investigation,

Data curation, Writing—Original draft, Writing—Review & editing

References

Adams, T. M., & Holland, C. C. (2018). Streaming media in an uncertain

legal environment: A model policy and best practices for academic libraries. Journal

of Copyright in Education & Librarianship, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.17161/jcel.v1i2.6550

Beisler, A., Bucy, R., & Medaille, A. (2019). Streaming video database

features: What do faculty and students really want? Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 31(1), 14–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2018.1562602

Cooper, D. M., Ruediger, D., & Skinner, M. (2022, June 9). Streaming

media licensing and purchasing practices at academic libraries: Survey results.

https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.316793

Dixon, J. A. (2017, September 7). The

Academic Mainstream | Streaming Video. Library Journal. Retrieved November

3, 2022, from https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/academic-mainstream-streaming-video

Dotson, D. S., & Olivera, A. (2020). Affordability of course

materials: Reactive and proactive measures at The Ohio State University

Libraries. Journal of Access Services, 17(3), 144–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/15367967.2020.1755674

Emery, J., & Loftis, E. (2020). Portland State University Library

General Collections Guidebook. https://pdx.pressbooks.pub/librarycollectionsguide/

farrelly, d (2016). Digital Video -

Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily wading into the stream. Information

Today, Inc. Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://www.infotoday.com/cilmag/nov16/farrelly--Digital-Video--Merrily-Merrily,-Merrily-Merrily-Wading-Into-the-Stream.shtml

farrelly, d., & Hutchison, J. (2014). ATG special report: Academic

library streaming video: Key findings from the national survey. Against the Grain, 26(5). https://doi.org/10.7771/2380-176X.6852

Grove, T. M. (2021). Academic library video services: Charting a post-COVID

course. Pennsylvania Libraries, 9(2). 101–110. https://doi.org/10.5195/palrap.2021.262

Hill, K., & Ingram-Monteiro, N. (2021). What patrons really want (in

their streaming media): Using focus groups to better understand emerging

collections use. The Serials Librarian, 80(1–4), 30–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2021.1873701

Ithaka S+R. (2023). About. https://sr.ithaka.org/about/

Keenan, T. M. (2018). Collaborating to improve access of video for all. Reference Services Review, 46(3), 414–424. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-03-2018-0028

Lai, J., & Widmar, N. O. (2021). Revisiting the digital divide in the

COVID ‐19 era. Applied Economic

Perspectives and Policy, 43(1),

458–464. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13104

Lear, C. (2022). Controlled digital lending of video resources: Ensuring

the provision of streaming access to videos for pedagogical purposes in

academic libraries. Journal of Copyright

in Education and Librarianship, 5(1),

1-19. https://doi.org/10.17161/jcel.v5i1.14807

Loftis, E. (n.d.). Streaming Media

Overview. Retrieved November 9, 2022, from https://pdx.pressbooks.pub/librarycollectionsguide/chapter/streaming-media-overview/

Loftis, E., & Keyes, J. (2019).

Navigating the Sustainable Stream. Timberline Acquisitions Institute, Mt.

Hood, OR, United States.

MacDougall, R., & Ruediger, D. (2023). Teaching with Streaming

Video: Understanding Instructional Practices, Challenges, and Support Needs.

Ithaka S+R. https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.318216

Peacock, R., & Vecchione, A. (2020). Accessibility best practices,

procedures, and policies in Northwest United States academic libraries. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46(1), 102095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.102095

Portland State University. (2022). Facts: PSU By the

Numbers. Portland State University. Retrieved

November 8, 2022, from https://www.pdx.edu/portland-state-university-facts

Portland State University. (2023). Standard for Accessible Digital

Procurement. Portland State University. Retrieved November 8, 2022, from https://www.pdx.edu/technology/standard-accessible-digital-procurement

Rapold, N. (2014, February 14). Even good films may go to purgatory. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/16/movies/old-films-fall-into-public-domain-under-copyright-law.html

Rodgers, W. (2018). Buy, borrow, or steal? Film access for film studies

students. College & Research

Libraries, 79(4). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.79.4.568

Tanasse, G. (2021). Choice White

Paper: Implementing and Managing Streaming Media Services in Academic Libraries.

Choice360. http://choice360.org/ librarianship/whitepaper

VanUllen, M.K., Mock, E., & Rogers, E. (2018). Streaming video at

the University at Albany Libraries. Collection and Curation, 37(1), 26–29.

https://doi.org/10.1108/CC-01-2018-004

Wang, J., & Loftis, E. (2020). The library has infinite streaming

content, but are users infinitely content? The library catalog vs. vendor

platform discovery. Journal of Electronic

Resources Librarianship, 32(2),

71–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2020.1739818

Whitten, S. (2019). The death of the

DVD: Why sales dropped more than 86% in 13 years. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/11/08/the-death-of-the-dvd-why-sales-dropped-more-than-86percent-in-13-years.html

Appendix A

Semi-Structured Interview Guide

Semi-Structured

Interview Guide

Introduction

The ways that instructors can work with video content is evolving rapidly

with the ascendancy of streaming platforms, including those the library

licenses or are made freely available, over older formats like VHS and DVD.

Within this context, the library is conducting a study to understand the

possibilities for fostering instructional use of video content at our

university. I’d like to ask you questions about your current use, preferences,

and future plans for incorporating video content in your teaching, and

perspectives on the role that the library can play towards that.

Before we begin, I’d also like to acknowledge that the landscape of

available video content for educational use can be incredibly complicated,

especially in terms of copyright terms and pricing models. Those complexities

are not the focus of our conversation, but of course they cannot be divorced

from how we can use video content in our teaching. As we go please feel free to

request we pause at any point if you’d like further explanation or

clarification about video content in the context of the broader educational

media landscape or any other aspect of our discussion.

Current Practices

I’d like to begin by exploring how you teach with video content, including

VHS, DVD, and the content provided through streaming platforms.

- Do you currently use any video content in your

classes?

»

If yes, Briefly walk me

through what kinds of content you are using, and in what format/platform and

length?

▪

For which classes

do you use this content in?

▪

How does the

content contribute to the pedagogical goals of the class?

»

If no, why is that? [and

if they have never used video content in their classes, skip to question 3]

- How do you determine which video content you use in

your classes?

»

At what point in

developing a course do you identify opportunities to include this content? Do

you typically have very specific titles in mind?

»

Where do you

typically look for content?

»

To what extent do

delivery affordances determine whether you incorporate a specific video

offering into your course? (e.g., delivery platform, accessibility options)

»

Do you consult with

any other people to identify opportunities to incorporate video content into

your class offerings?

- To what extent are your current needs for

incorporating video content into your courses being adequately met?

»

Has the pandemic

changed your needs for incorporating video content into your courses in any

way?

»

Are there any

recent examples where you encountered barriers to incorporating specific

content into your class? [e.g., unavailability of specific titles, copyright

complexities]

»

If yes, What were the

barriers, and how did you work around them?

▪

Did you work with

any others to mitigate those barriers?

▪

Is there anything

else that could have been done to alleviate these challenges?

Next, I’d like to learn more about how your expectations are evolving

around how video content can be incorporated in your classes.

- Has the availability of streaming content changed

how you integrate video content into your teaching?

»

What do you see as

the greatest affordances of streaming content for your teaching?

»

Are they any

downsides to incorporating streaming content into your teaching?

»

Is there anything

that could be improved about streaming content offerings and/or functionalities

to maximize the opportunities to incorporate it into your teaching?

- Has the availability of streaming content changed

your expectations about how the costs of the video content should be

covered?

»

Are there any

instances where it is acceptable to require students to pay directly to access

video content for educational purposes?

»

How do your

expectations with video relate to your expectations for how other forms of

course content are paid for? E.g., textbooks, journal articles.

»

What are the top

factors that you think are important for determining the extent to which the

university covers the costs of video content? Which part(s) of the university

should cover those costs?

- What kinds of resources or other supports would help

you identify and assess opportunities for including video content into

your classes?

»

Would additional

information about pricing structures, available titles, or format types affect

your decision-making about what content to assign?

»

Ideally, how would

you like to get this information and from whom?

Wrapping Up

I’d like to finish up with a few questions that put your perspectives into

the broader context of your field and look towards future developments and

needs.

- How does your use of video content in your teaching

compare to the practices of your peers?

»

Are there any kinds

of video content or functionality that you would like to see more of?

»

Are there any

developments in the areas that you teach that may affect how you or your peers

would like to teach with video content in the next five years?

- Is there anything else that is important for me to

know about how you or your peers incorporate video content into teaching?