Research Article

Public Libraries and Health Promotion

Partnerships: Needs and Opportunities

Noah Lenstra

Associate Professor of

Library & Information Science

University of North Carolina

at Greensboro

Greensboro, North Carolina,

United States of America

Email: lenstra@uncg.edu

Joanna Roberts

Graduate Research Assistant

University of North Carolina

at Greensboro

Greensboro, North Carolina,

United States of America

Email: jyroberts871@gmail.com

Received: 21 Sept. 2022 Accepted: 17 Nov. 2022

![]() 2023 Lenstra and Roberts. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2023 Lenstra and Roberts. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30250

Abstract

Objective – Across North America, public libraries have increasingly served their

communities by working with partners to connect patrons to essential healthcare

services, including preventative. However, little is known about the extent of

these partnerships, or the need for them, as seen from the perspective of

public library workers. In this study, we set out to address the following

research question: What needs and opportunities are associated with health

promotion partnerships involving public libraries?

Methods – Using snowball sampling techniques, in September 2021, 123 library

workers from across the state of South Carolina in the United States (US)

completed an online survey about their health partnerships and health-related

continuing education needs; an additional 19 completed a portion of the survey.

Results – Key findings included that library capacity is limited, but the desire

to support health via partnerships is strong. There is a need for health

partnerships to increase library capacity to support health. Public libraries

already offer a range of health-related services. Finally, disparities exist

across regions and between urban and rural communities.

Conclusion – As an

exploratory study based on a self-selecting sample of public library workers in

a particular state of the US, this study has some limitations. Nonetheless,

this article highlights implications for a variety of stakeholder groups,

including library workers and administrators, funders, and policy makers, and

researchers. For researchers, the primary implication is the need to better

understand, both from the public library worker’s perspective and from the

(actual or potential) health partner’s perspective, needs and opportunities

associated with this form of partnership work.

Introduction

On November 21,

2022, the Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health published the

research article “Supporting Mental Health in a Public Library Context: A Mixed

Methods Brief Evaluation” (Oudshoorn et al., 2022). The authors explored the

potential for a collaboratively constructed mental health wellness hub situated

in a Canadian urban library, finding that this form of co-location was desired

by patrons, mental health hub staff, and library staff.

As discussed

below, the topic of public libraries and public librarians as health promotion

partners has been increasingly explored by a range of scholars representing a

range of disciplines. Despite an increase in calls to better understand the

current potential of public library participation in health promotion (Flaherty

& Miller, 2016), most studies on this topic have either been case studies

of particular communities (as in Oudshoorn et al., 2022), or focused

exclusively on single topics, such as consumer health at the library reference

desk (e.g., Arnott Smith, 2011) or mental health (Oudshoorn et al., 2022).

To give one

example: there is a growing literature on social workers in public libraries

(Ogden & Williams, 2022), which suggests that this integration is neither

easy, nor inevitable, but instead requires different actors and stakeholders

getting to know each other and find common ground (Wahler et al., 2022).

Library workers recognized the need for someone like a social worker, but

perhaps that need could also be filled by other forms of partnership not being

explored in any sort of broad-scale way. For instance, Baum et al. (2022), the

authors of a recent study on the topic of social work-public library

partnerships from the U.S. state of Florida, found that:

All seven branch managers [interviewed] expressed enthusiasm when

discussing the trend of social workers in libraries, noting patron struggles

with food insecurity, homelessness, immigration, substance misuse, mental

health challenges, and overall economic disadvantage as major motivating

factors behind their support for including them in public libraries. (p. 14)

The range of

social and health needs identified by these public librarians pointed to the

need for a complementary range of partnerships, not only with social workers,

but also with others in the health and social services sectors. Nevertheless,

we lack a broader understanding of the current state of needs and opportunities

associated with public library participation in community health partnerships.

With this study, we sought to begin to fill this gap.

Literature Review

Discussions of health

promotion in public libraries are as old as the profession of public

librarianship itself (Mon, 2021; Rubenstein, 2012). Most public library-based

health promotion partnerships have been highly localized, involving librarians

working with local health partners to develop innovative solutions to local

problems, such as the example of a bookmobile in rural Georgia transporting a

county nurse in the 1940s (Rubenstein, 2012). In the 1960s, some urban

libraries started developing community information and referral systems to

refer patrons in need to the services of other agencies, including health

agencies (Arnott Smith, 2011). More recently, in 1992, a public librarian in

Stratford, CT, developed a partnership with a local teen counseling group and

an aerobics instructor to develop a physical and mental health support group

for teenagers at the library (Lenstra, 2018).

Through this

literature review, we identified three themes in recent literature on this

topic:

- The library as community space for access to health-related

services

- The library as a space for social workers and health workers

- The critical, if understudied, role of library workers in these

partnerships.

The Library as Community Space for Access to Health-Related

Services

The idea of the

public library as a community space has become more prominent (e.g., Klinenberg, 2018; Mattern, 2007), shaping discussions

of how health promotion activities occur in public libraries. As shown in a

state-wide survey of Pennsylvania library directors, health services in public

libraries include, in different places, access to social workers, summer meals,

bathrooms, a respite from the elements for individuals experiencing

homelessness, nutrition classes, telehealth, and a range of other health and

social services (Whiteman et al., 2018). This trend

continued during the COVID-19 pandemic, when libraries were framed as

convenient spaces to distribute tests, host immunization clinics, support

access to telehealth, and even assist in efforts to address food insecurity

(e.g., State of Wisconsin, 2022; Virginia Department of Health, 2021).

An additional

facet of the literature on library as space has been research on libraries as

crucial nodes in disaster response (Liu et al., 2017;

Tu-Keefner, 2016), particularly research on libraries in areas prone to

hurricanes (Hamilton, 2011; Jaeger et al., 2006; Mardis

et al., 2020; Veil & Bishop, 2014). This trend has continued during the

COVID-19 pandemic, with research published on the roles of public libraries and

librarians during this emergency (Smith, 2020).

Another notable

trend was that of the public library as a support for child and family health.

Studies have been done on libraries as hosts of summer meal programs (De La

Cruz et al., 2020; Sandha & Holben, 2021), nutritional education classes

(Freedman & Nickell, 2010), physical activity classes (Bedard et al.,

2020), oral health programs (Woodson et al., 2011), and more generally as

institutions that support health, including mental health, among vulnerable teenagers

and youth (Banas et al., 2020; Campana et al., 2022; Grossman et al., 2021;

Winkelstein, 2019).

Providing direct

medical support for adults through telehealth was a newer option being

explored. Santos (2021) provided a case study of this effort in a small rural

library in Pottsboro, Texas. DeGuzman et al. (2021) found great potential for

libraries to become hubs for providing health access to rural populations with

little or no broadband access.

The Library as a Space for Social Workers and Health Workers

There has also

been interest in placing social workers and other health workers in public

libraries since the San Francisco Public Library began the practice in 2009 (Esguerra, 2019). This work emerged in part due to an

increasingly public realization that public libraries were sites of public

health incidents, including drug overdoses. Feuerstein et al. (2022) surveyed

five states (n=356) for information on instances of substance abuse on library

property, and how libraries planned and prepared for this occurrence. The

researchers found that alcohol and drug use was common on library property, but

most libraries did not have on-site medical help, such as Naloxone. They also

found that librarians would like more training on how to handle these situations.

Giesler (2021)

studied perceptions of social workers in public libraries, finding differences

in how the position was utilized across library systems. Social workers might

be primarily focused on training other library staff to recognize and empathize

with specific patron populations, such as homeless populations. They could also

interact directly with library patrons to offer services. Gross and Latham

(2021) also found this benefit in staff training by the six library

administrators who already employed social workers in the Southeast US (n=52).

Johnson (2021) and Wahler et al. (2022) described the components of “readiness”

required for both a public library and the participating university when

considering a social work student internship at a library.

Other health

liaisons have been found to be helpful for library staff assisting patrons with

complex needs. Homeless patrons often used the library for various reasons, as

described by Adams and Krtalić (2021). They found that the presence of a

community health worker focused on the needs of the homeless population helped

the library and its staff to better understand and provide for those needs by

reducing barriers to services.

Other

researchers considered alternative models of placing health liaisons in

libraries. Both interprofessional student internship models and the training of

library staff in health information have been the focus of research.

Pandolfelli et al. (2021) considered the lessons from different experiential

learning opportunities for students (n=21) from a variety of professions:

general health courses at the undergraduate level, and masters’ level social

worker, library science, and public health students. This study of a joint

training experience for the students allowed for both support and building

common ground between professions and the students involved when working in a

library setting. This sort of inter-professional training model has been

deployed at the University of Missouri, where Library & Information Science

students took courses on public health as part of an experimental, federally

funded project (Bossaller et al., 2022).

Draper (2021) conducted a feasibility study to explore

the potential for collaboration between nutrition educators and public

libraries. Draper found that while there were extensive overlapping goals

between U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance

Program Education program (SNAP-Ed)—which is an evidence-based program that

helps people lead healthy, active lives by partnering with state and local

organizations—and public libraries, library staff had little knowledge of the

federal program, with only 1 of the 14 participants having any understanding of

SNAP-Ed and how it could support libraries.

In Spring 2022,

the Texas-based St. David’s Foundation announced a new $1.5 million initiative

to support what they are calling Libraries for Health. The foundation is

collaborating to broaden access to mental health services for rural residents

by placing non-clinical mental health workers at the public libraries in

Central Texas. The non-clinical mental health worker initiative is modeled on

peer navigator programs found in some urban libraries across the country.

Crucially, the program includes a strong evaluation component, led by The Rand

Corporation (Carey, 2022).

The Under-Studied Role of Library Workers

As public libraries were increasingly seen as

opportune spaces for health promotion services, the roles of library workers in

administering these services were sometimes overlooked. The absence of library

workers from these discussions could sometimes lead to burnout and staff

feeling overwhelmed, as they felt they were being asked to take on more and

more in their daily work (Freeman & Blomley, 2019).

This perception increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many librarians

suffered trauma as front-line workers (Comito & Zabriskie, 2022). The

question of what capacity public library workers have to participate in

community health partnerships remains under-studied.

When library workers were mentioned in research on

this topic, researchers tended to focus on how to most effectively train

library workers to field reference questions related to consumer health

information in ways analogous to the work done by medical or health sciences

librarians. Derosa et al. (2021) described a partnership between Weill Cornell

Medicine library and the city of Brooklyn, New York, focused on using a

train-the-trainer model for library workers by providing training in how to

better serve patrons requesting information about health issues. Other

researchers have focused on the preparedness of public library workers to

support patrons in crisis. Wong et al. (2021) reported on the ability of Pennsylvania

public librarians (n=100) to provide health information on substance abuse

issues over the phone and found that there was a wide variation between

libraries. Brus et al. (2019) surveyed public library staff in Australia and

found a lack of confidence in dealing with patrons with complicated social

issues such as mental health and homelessness. Malone and Clifton (2021)

explored this idea in a five-year study of the Oklahoma public library system

(n=106 staff, n=67 libraries) to certify existing public library staff in

specialized training from the Medical Library Association. Fewer researchers

have focused on how to foster cross-sector collaborations most effectively

between public librarians and those working in the community health sector

(Lenstra & McGehee, 2022).

Aims

In this study, we set out to address the following

research question: What needs and opportunities are associated with health

promotion partnerships involving public libraries?

We framed this question from the perspective of public

library workers. Future research on this topic could investigate the question

from the perspective of actual or potential public library partners.

Methods

To understand the needs and opportunities associated

with South Carolina public library participation in health initiatives, we

designed a survey through a collaborative process that included the following

steps:

1.

A review of survey instruments used in previous

surveys of the topic of public libraries and community health, including those

in Bertot et al. (2015), Feuerstein-Simon et al. (2020), and Whiteman et al.

(2018).

2.

Codifying the range of health partnerships involving

public libraries discussed in previous literature to ensure the survey inquired

about different partnership configurations.

3.

An alignment of the research instrument with the

priorities of the South Carolina Center for Rural & Primary Healthcare (SC

CRPH), a partner in this study.

4.

Coordination with the State Library of South Carolina

around framing this topic.

After development and testing, the research methods were approved by the

Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro

(Study #IRB-FY22-71).

There is no comprehensive directory of public library employees in South

Carolina, either at the state or local levels. According to the U.S. Institute

of Museum & Library Services (IMLS), in FY2019 – the most recent year for

which data was available at the time of this writing – the total staff of all

public libraries in South Carolina is 2,112 (Pelczar, 2021). This number

includes 514 credentialed librarians and 1,598 other employees, including

paraprofessionals, groundskeepers, and security staff, among others. There are

42 public library systems in the state. Although we were most interested in

hearing from librarians, the survey was designed such that it was open to any

employee of a public library in South Carolina.

To reach these employees, the researchers used a form of snowball

sampling in which individuals and institutions that were pillars of the public

library community in South Carolina were asked to distribute the survey to

their networks on behalf of the researchers. These institutions included the

State Library of South Carolina, the Network of the National Library of

Medicine, the South Carolina Library Association, and the SC CRPH itself.

The survey was distributed over four weeks in September 2021, an extremely

difficult moment in South Carolina and in the world. For logistical reasons,

the survey had to be distributed during this moment in time. September 2021 was

in the middle of the global pandemic. These logistical reasons centered around

the temporal constraints of the South Carolina Center for Rural & Primary

Healthcare, which wished to better understand this topic prior to releasing

financial awards in Spring 2022 to South Carolina public libraries wishing to

embark on novel health partnerships in their communities.

During the four weeks the survey was open, the researchers monitored the

response rate, generating a weekly map of where respondents were coming from,

at the county level. This response rate informed subsequent snowball sampling

techniques, which focused on attempting to secure complete saturation across

all counties in the state of South Carolina. More information on recruitment

and sampling can be found in Lenstra and Roberts (2022).

Analysis

Descriptive

statistics were calculated for all closed-ended survey responses, while

thematic coding was conducted to analyze open-ended responses. To further

analyze the data and to generate regional and other trends, the researchers

used the demographic information respondents provided about their job titles

and library locations to generate comparisons. Following federal practices established by the IMLS, rural and urban

differences were established using the procedures set by the National Center

for Education Statistics, a unit of the U.S. Department of Education.

We organized

this article around the sections of the survey that centered on partnerships

that included public librarians and actors in the health and social service

sectors, including results that helped indicate why such partnerships would or

would not be desirable. The survey included a range of questions on the broader

topic of needs and opportunities associated with public libraries as

institutions embedded within community health ecosystems. Readers interested in

accessing broader survey results, including the dataset itself and the results

of the thematic coding of open-ended responses, may do so at the open access

white paper published by Lenstra and Roberts (2022).

Limitations

As with any nonprobability sampling technique, there were limitations to

this approach, which centered around the fact that statistical generalization

to the broader population studied is impossible. Nonetheless, we chose

nonprobability sampling as the best way to secure a broad sample of the South Carolina

public library community within the timeframe of the project.

Additional limitations derived from the survey format itself. It was

possible that different respondents may have interpreted some of the survey’s

prompts in different ways. For instance, the survey did not specify what was

meant by “access to health literacy,” and thus this prompt and others like it

may have been interpreted in different ways. Despite these limitations, this

survey and its results provided an unprecedented window into perceptions,

needs, and opportunities associated with public library and health

partnerships.

Results

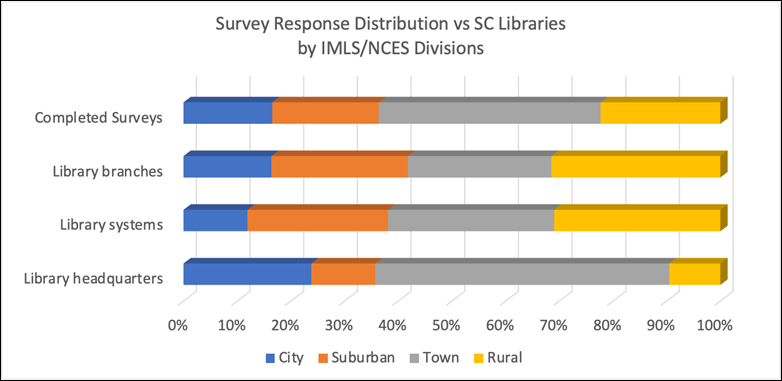

In general

terms, the sample of respondents roughly aligned with the distribution of

public libraries across South Carolina. Figure 1 shows that the distribution of

the 123 respondents who fully completed the survey roughly aligned with the

distribution of South Carolina libraries. The number of “completed responses” refers to the number of library

workers who totally completed the survey. There were 21 additional respondents

who gradually dropped out of the survey after completing only a portion. All

those who dropped out did so after completing at least a full page of

questions. More information on the sample appeared in Lenstra and Roberts

(2022), and the number of respondents for individual questions can be found in

the Appendix.

Figure 1

Survey response

distribution compared to the distribution of public libraries across the state

of South Carolina.

The vocabulary

used in Figure 1 corresponds to the three ways that the IMLS used to assess the

geographical distribution of public libraries across the nation: 1) Library

branches (outlets, in the nomenclature of the IMLS) referred to library

branches and bookmobiles, 2) Library systems (Administrative Entities MOD in

the nomenclature of the IMLS) referred to the geographic spread of multi-branch

library systems, and 3) Library headquarters (Administrative Entities ADD in

the nomenclature of the IMLS) referred to the locations of the headquarters of

multi-branch library systems.

The Desire to Collaborate with Health Workers is Strong, But Capacity is Limited

Nearly every

respondent reported a need for a health worker or a health liaison to help them

serve the public in their library: over 90% said that if outside help were

available, they could see a need for a health or social worker at their

libraries.

However, when

respondents were asked if they would like to have specific types of health

workers or health liaisons available at their libraries, interest diminished.

Only 74% of respondents were interested in, or currently had available, social

workers at their libraries. Social workers were the most desired type of health

liaison (Table 1).

Table 1

Public Library

Worker Interest in Having Health Professionals Available to the Public at their

Libraries

|

Health Professional (n=126) |

Not interested |

Offered |

Interested – Not Offered |

|

Social

workers |

26% |

23% |

51% |

|

Nurses |

37% |

12% |

51% |

|

Health

educator |

25% |

27% |

48% |

|

Medical

students |

48% |

4% |

48% |

|

Community

health workers |

29% |

24% |

47% |

|

Social

work students |

44% |

13% |

43% |

|

AmeriCorps

or other volunteers |

40% |

21% |

39% |

|

Other

health-related professional |

69% |

8% |

23% |

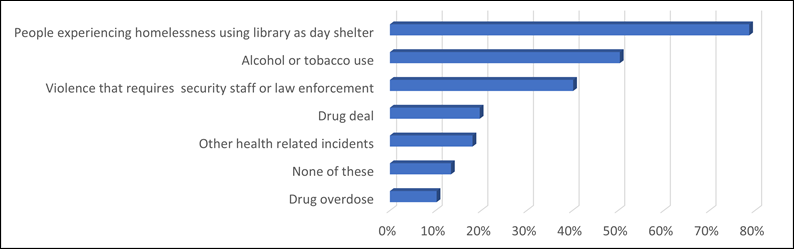

One reason for

this perceived need may relate to the prevalence of health-related incidents

that occur on library property. Nearly 80% of respondents reported that people

experiencing homelessness used their public libraries as day shelters, and

between 10-50% reported a range of other incidents on library properties,

including drug deals, physical violence, and overdoses. Librarians also wrote

open-ended comments about health-related incidents they had witnessed at their

libraries, including seizures and heart problems (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Medical and

health related incidents occurring on public library property. (n=127)

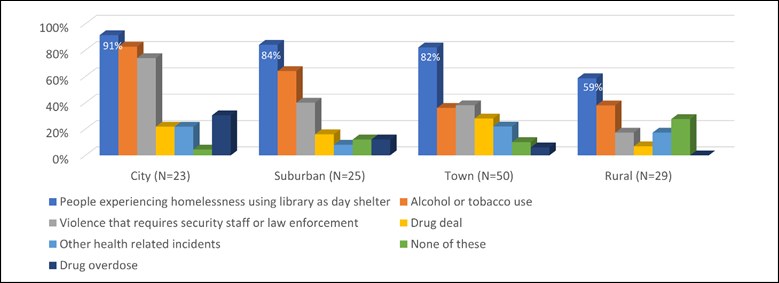

City librarians

were most likely to report all the incident types asked about, except for drug

deals (Figure 3). Data suggested, however, that these sorts of incidents

occurred in public libraries across the state. Less than 30% of rural

respondents said no health-related incidents had occurred at their properties.

As open public spaces, health issues occurring in communities tended to also

occur in public libraries.

Figure 3

Medical and

health related incidents occurring on public library property, by type of

community served. (n=127)

In any case, one

reason for the difference between perceived need for outside help in general,

and perceived need for specific forms of outside help, related to limited

library capacity to develop new initiatives. As one respondent wrote in an

open-ended comment: “We do not have enough staff and really cannot handle any

more programs. Even when partnering with others, it takes staff time, and we

just cannot do it anymore due to not enough staff.”

A Need for Health Partnerships to Increase Library Capacity to Support Health

Respondents did not always have the partnerships that

would enable them to bring other types of health services to their libraries,

or to refer library patrons to appropriate health or social service agencies.

Public libraries typically had close connections with agencies that support the

social determinants of health (SDoH), including educational institutions, parks

& recreation units, and non-profits. These reported close relationships

could position public libraries to effectively facilitate community

conversations on health needs in ways that would bring more voices into local

health planning and policy making.

Librarians also reported offering a range of services

that support addressing the SDoH, including access to technology, literacy,

education, food, legal aid, and employment. Across the state, many public

libraries have hosted a wide array of services that support public health and

the SDoH, with more than 40% reporting they have hosted everything from food

drives to fitness classes, farmers’ markets, summer meals, health fairs, and

blood drives.

Less robust were the relationships between public

libraries and agencies specifically in the health sector, and less common were

library services that directly supported access to healthcare. Less than 50% of

respondents reported close relationships with any organization in the

health sector (Table 2).

Table 2

Closeness of

Relationships Between Public Libraries and Potential Partners (n=127)

|

Department/Institution |

Very close or somewhat close |

Not very close |

|

K-12

Schools |

89% |

11% |

|

Early

education providers, including daycares |

88% |

12% |

|

Local

non-profit organizations |

85% |

15% |

|

Parks

& Recreation Unit |

61% |

39% |

|

Colleges

or universities |

60% |

40% |

|

Health

department |

44% |

56% |

|

Hospital

or healthcare system(s) |

41% |

59% |

|

Health

coalition or alliances |

41% |

59% |

|

SNAP-Ed

implementing agency |

41% |

59% |

|

Department

of Justice / |

31% |

69% |

|

WIC

Clinics |

29% |

71% |

Despite being

less common currently, there existed a sizable number of early adopters and

health champions within the South Carolina public library sector who reported

already working closely with health partners. Around one quarter of respondents

said they have had health liaisons and telehealth services available at their

libraries. Around one-third of respondents reported the presence of a health

champion employed within their libraries, someone who championed health

services and partnerships and could be utilized as an entry point for programs

and partnerships.

Responsive Health Services in South Carolina Public Libraries

Nevertheless,

most respondents thought that individuals in their communities look to the

library as a safe and trusted space, used both to access health literacy and to

access health services, and most librarians saw health equity as a priority for

their libraries.

The most common

way in which public librarians themselves directly supported health centers was

around information access, with 75% of respondents saying their libraries

supported access to health information in general, 63% supporting health

literacy, and 57% reporting they provided help identifying and using local

health resources. Less commonly reported were informational referrals to

appropriate health or social service agencies (43%). More than 60% of

respondents said their libraries supported access to related services during

the COVID-19 pandemic, including 42% who offered immunization clinics for

COVID-19, and 29% who offered COVID-19 testing services. In the context of the

ongoing opioid crisis, over 20% of urban librarians, and over 10% of rural

librarians, reported having naloxone available at their libraries.

Regional and Rural/Urban Disparities

In general

terms, rural librarians were broadly interested in doing more to support

health, and compared to their more urban peers, have had fewer opportunities,

and less capacity, to do so. For instance, most rural librarians reported

interest in offering mental health first aid trainings, while most urban

librarians had already offered these trainings.

Rural librarians

were also those least likely to have had formalized health partnerships, with

50% reporting no partners in programmatic or funded health initiatives, meaning

they were less likely to have partnerships to support health. Given this

situation, rural respondents were broadly interested in whatever resources they

may be able to bring to their communities. Thinking about what kind of health liaison

would be the best fit for a public library, respondents across the state

articulated a preference for fully credentialed health liaisons, rather than

for students, volunteers, or other health workers in training. Rural

librarians, however, were broadly interested in whatever health liaisons they

could bring to their libraries, regardless of credentials.

Continuing Education and Support Needs

Only 10% of respondents reported no barriers to

supporting health at their libraries, suggesting a need for more robust

continuing education and sustained support. Top priorities for continuing

education as reported by survey respondents included how to get started

supporting health at public libraries, how to sustain these efforts, and how to

build partnerships around this topic. Major barriers to supporting health

included a perceived lack of expertise and funding. Librarians reported wanting

to learn more about this topic from other librarians who have directly dealt

with these issues at their libraries.

Looking to continuing education needs, urban

librarians had markedly different continuing education priorities, with

sustainability and evaluation coming out on top (Table 3). In contrast, for all

other parts of the state, there was more interest in introductory topics, with

how to get started and how to partner rated as top priorities for continuing

education. It appeared that urban libraries had, in general, already started

these partnerships, and were looking to better sustain and evaluate them, while

all other libraries were looking to get started with these types of

partnerships.

Although it was not always identified as a top

priority for continuing education, evaluation emerged as a significant

obstacle. Most respondents indicated that they were not doing anything to

evaluate or track the impacts of their libraries on health. One respondent

wrote:

We don't really

have a way to track this info. We did weight loss programs, but the partner

tracked progress and no long-term info available. We have done nutrition and

health programs with our hospital targeting diabetes and heart disease,

distributed food during 2020, have had exercise programs for seniors, walking

programs, etc. We have sponsored CPR training courses for the public.

An effective evaluation system would need to consider

the myriad and evolving ways in which public libraries support health. Due to

an absence of evaluation systems, the contributions of public libraries to

community health were often invisible, and thus underappreciated and under-supported.

Table 3

Top Priorities

for Library Continuing Education, by Community (n=121)

|

Urban (n=20) |

Suburban (n=24) |

Town (n=50) |

Rural (n=27) |

|

Sustainability (70%) |

How to get started (54%) |

How to get started (62%) |

How to get started (59%) |

|

How to evaluate (65%) |

How to partner (tied) (54%) |

How to partner (56%) |

How to partner (tied) (59%) |

|

How to get started (60%) |

Sustainability (tied) (54%) |

Marketing (48%) |

Marketing (56%) |

|

How to partner (50%) |

Marketing (38%) |

Sustainability (46%) |

Sustainability (48%) |

|

Marketing (30%) |

How to evaluate (21%) |

How to evaluate (36%) |

How to evaluate (tied) (48%) |

Discussion

Most respondents to this survey saw a role for their

public libraries in health promotion, equity, and access. Nevertheless,

obstacles large and small prevented the South Carolina public library workforce

from doing as much as they would have liked to support health. In urban South

Carolina, funding, sustainability, and evaluation were major challenges, while

more rural areas were challenged in discovering how to get started and how to

build partnerships. Throughout the state, respondents saw a need for help

weaving health into the operations of a public library without overwhelming or

over-burdening the library staff. Librarians needed technical assistance, as

well as support for funding and evaluation, to make their community-based

health initiatives sustainable and impactful over the long-term.

In this study, we identified a handful of library

systems that have embraced health services and partnerships at their libraries,

including in their strategic plans. The Charleston County Public Library is one

example (CCPL, 2021). Their strategic plan explicitly called for the library to

“empower learners of all ages to manage their lifelong physical and mental

health,” “empower individuals with the knowledge to make healthy food choices,”

and “empower individuals to obtain and understand basic health information”

(CCPL, 2021). Finding ways to meaningfully enable these early adopters and

their leadership teams to share their successes and challenges with other

libraries could potentially drive innovation forward.

To extend this trend, these library health champions

could share best practices, advocate for promising partnerships, and share

common successes and challenges through the peer-to-peer infrastructure that

exists for professional development and continuing education among public

librarians.

There is a strong tradition of training programs for

public librarians focused on increasing their comfort and confidence with

health information. This training has been, historically, offered by medical

and academic health science librarians (e.g., Malone & Clifton, 2021). The

successful deployment of peer-to-peer training among public librarians, perhaps

in a learning cohort, could provide public librarians with a different type of

training program, one focused less on comfort and confidence with health information

sources, and more on comfort and confidence working collaboratively with

community health partners.

Our goal should be to find ways to enable the health

and public library workforces to mutually build each other up, with the two

workforces adding value to each other, and adding capacity to their abilities

to support the communities they serve together.

A second promising practice would be to find ways to

better connect library directors to local health leaders and to other library

leaders. These connections could be made not only at the library executive

director level, but also at the deputy director and branch/division manager

levels. Survey results suggested these library middle managers were less

connected to local health partners than library directors. In any case, at the

leadership level, the focus is less on cultivating library health champions,

and more on how we make these partnerships work, administratively.

Library directors and leaders need help understanding

how to integrate health into library services in ways that avoid the burnout of

their staff, and that are sustainable over time. They also need help

integrating timely topics, such as telehealth, into their libraries. Evaluation

is a perennial issue in public libraries, and thinking strategically about

health in public librarianship is another need.

Evaluation of how public libraries support health is

also essential. A starting point for developing this type of evaluation should

be a discussion between health organizations and public libraries that promotes

understanding of the different structures and needs of each group. Finding ways

to embed documentation into these partnerships is crucial for their long-term

viability.

Conclusion

In this

exploratory study, we highlighted implications for a variety of stakeholder

groups, including those working in the health sector at both local and state

levels, as well as library workers and administrators, funders and policy

makers, and researchers.

Given the

limited and self-selecting sample, comparisons between rural and urban public

library workers remained tentative. Additional research using a randomized

sampling model that employs cluster sampling to ensure a strategically selected

distribution of public library workers representing the rural-urban continuum

could enable a more nuanced understanding of the unique needs of public library

workers within different types of communities.

We are only

beginning to understand needs and opportunities associated with public library

participation in community health initiatives. Additional research must also

consider this topic from the perspective of community health partners. How

ready are community health workers and social workers to partner with public

librarians? This topic also needs to be addressed to holistically understand

this topic.

More generally,

many of the findings of this survey deserved more nuanced explanation through

interview-based research. The survey results showed what was happening in South

Carolina’s public libraries; it cannot answer why things were the way they

were. For instance, the survey found that in one-third of respondents’

libraries, a health champion was employed. How did these health champions

within the public library workforce come to be? What policies, practices, and

community forces led to health champions working at these libraries? These are

topics interview-based and case study research could help to illuminate.

Although

tentative, the findings from this project unambiguously demonstrated interest within

the South Carolina public library workforce to support health, particularly

though partnerships that would bring health workers to their libraries.

Although additional research is needed to build up our understanding of this

topic, this survey showed a great potential for impacts associated with public

library health partnerships.

Author Contributions

Noah

Lenstra: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding

acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review &

editing Joanna Roberts: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation,

Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft

Acknowledgment

This research was made possible in part by the South

Carolina Center for Rural & Primary Healthcare grant #22-0035. We would

also like to thank our reviewers for their thorough critique of the manuscript,

which improved the manuscript in significant ways. We also want to say thank

you to the South Carolina public library and public health communities, who

shared feedback on early findings from this project at a South Carolina State

Library webinar and the South Carolina Public Health Association conference,

respectively.

References

Adams, C., & Krtalić,

M. (2021). I feel at home: Perspectives of homeless library customers on public

library services and social inclusion. Journal of Librarianship and

Information Science, 54(4), 779-790. https://doi.org/10.1177/09610006211053045

Arnott Smith, C. (2011). “The easier-to-use

version”: Public librarian awareness of consumer health resources from the

National Library of Medicine. Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet,

15(2), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/15398285.2011.573339

Banas, J. R., Oh, M. J., Willard, R., &

Dunn, J. (2020). A public health approach to uncovering the health-related

needs of teen library patrons. The Journal of Research on Libraries and

Young Adults, 11(1). https://neiudc.neiu.edu/hpera-pub/9/

Baum, B., Gross, M., Latham, D., Crabtree, L.,

& Randolph, K. (2022). Bridging the service gap: Branch managers talk about

social workers in public libraries. Public Library Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2022.2113696

Bedard, C., Bremer, E., & Cairney, J.

(2020). Evaluation of the Move 2 Learn program, a community-based movement and

pre-literacy intervention for young children. Physical Education and

Sport Pedagogy, 25(1), 101-117. https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2019.1690645

Bertot, J. C., Real, B., Lee, J., McDermott,

A. J., & Jaeger, P. T. (2015). 2014 digital inclusion survey: Survey

findings and results. Information Policy & Access Center (University of

Maryland); American Library Association. https://web.archive.org/web/20170403022504/http://digitalinclusion.umd.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/2014DigitalInclusionSurveyFinalRelease.pdf

Bossaller, J. S., Adkins,

D., Pryor, C. N., & Ward, D. H. (2022). Catalysts for Community Health

(C4CH). https://c4ch.missouri.edu/

Brus, J., Fulco, C,

Hornibrook, L., Monypenny, K., & Niranjan, P. (2019). Social issues in

public libraries: Supporting our staff. https://www.plv.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Social-issues-in-public-libraries-supporting-our-staff-2019.pdf

Campana, K., Mills, J. E.,

Kociubuk, J., & Martin, M. H. (2022). Access, advocacy, and impact: How

public libraries are contributing to educational equity for children and

families in underserved communities. Journal of Research in Childhood

Education, 36(4), 561-576. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2021.2017375

Carey, L. (2022, March 24).

Texas rural libraries will help with mental health access. The Daily Yonder.

https://dailyyonder.com/texas-rural-libraries-will-help-with-mental-health-access/2022/03/24/

CCPL: Charleston County Public Library. (2021). CCPL's strategic

vision for 2021-2024. https://www.ccpl.org/strategicvision

Comito, L., & Zabriskie, C. (2022). Urban library trauma study:

Final report. Urban Librarians Unite. https://urbanlibrariansunite.org/ults/

De La Cruz, M. M., Phan, K., & Bruce, J. S. (2020). More to offer

than books: Stakeholder perceptions of a public library-based meal programme. Public

Health Nutrition, 23(12), 2179-2188. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019004336

DeGuzman, P. B., Jain, N., & Loureiro, C. G. (2021). Public

libraries as partners in telemedicine delivery: A review and research agenda. Public

Library Quarterly, 41(3), 294-304. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2021.1877080

DeRosa, A. P., Jedlicka, C., Mages, K. C., & Stribling, J. C.

(2021). Crossing the Brooklyn Bridge: A health literacy training partnership

before and during COVID-19. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 109(1),

90–96. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2021.1014

Draper, C. L. (2021). Exploring the feasibility of partnerships between

public libraries and the SNAP-Ed program. Public Library Quarterly, 41(5),

439-455. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2021.1906615

Esguerra, L. (2019, January 4). Providing social service resources in a

library setting. Public Libraries Online. http://publiclibrariesonline.org/2019/01/providing-social-service-resources-in-a-library-setting/

Feuerstein-Simon, R., Lowenstein, M., Dupuis, R., Dolan, A., Marti, X. L.,

Harvey, A., Ali, H., Meisel, Z. F., Grande, D. T., Lenstra, N., &

Cannuscio, C. C. (2022). Substance use and overdose in public libraries:

Results from a five-state survey in the US. Journal of Community Health,

47, 344-350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-021-01048-2

Flaherty, M. G., & Miller, D. (2016). Rural public libraries as

community change agents: Opportunities for health promotion. Journal of

Education for Library and Information Science, 57(2), 143-150. https://doi.org/10.3138/jelis.57.2.143

Freedman, M. R., & Nickell, A. (2010). Impact of after-school

nutrition workshops in a public library setting. Journal of Nutrition

Education and Behavior, 42(3), 192-196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2009.07.003

Freeman, L. M., & Blomley, N. (2019). Enacting property: Making

space for the public in the municipal library. Environment and Planning C:

Politics and Space, 37(2), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654418784024

Giesler, M. (2021). Perceptions of the public library social worker:

Challenges and opportunities. The Library Quarterly, 91(4),

402–419. https://doi.org/10.1086/715915

Gross, M., & Latham, D. (2021). Social work in public libraries: A

survey of heads of public library administrative units. Journal of Library

Administration, 61(7), 758–775. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2021.1972727

Grossman, S., Agosto, D. E., Winston, M., Epstein, N. E., Cannuscio, C.

C., Martinez-Donate, A., & Klassen, A. C. (2021). How public libraries help

immigrants adjust to life in a new country: A review of the literature. Health

Promotion Practice, 23(5), 804-816. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248399211001064

Hamilton, R. (2011). The state library of Louisiana and public

libraries' response to hurricanes: Issues, strategies, and lessons. Public

Library Quarterly, 30(1), 40-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2010.525385

Jaeger, P. T., Langa, L. A., McClure, C. R., & Bertot, J. C. (2006). The 2004 and 2005 Gulf Coast hurricanes: Evolving roles and lessons

learned for public libraries in disaster preparedness and community services. Public

Library Quarterly, 25(3-4), 199-214. https://doi.org/10.1300/J118v25n03_17

Johnson, S. C. (2021). Innovative social work field placements in public

libraries. Social Work Education, 41(5), 1006-1017. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2021.1908987

Klinenberg, E. (2018). Palaces for the people: How social

infrastructure can help fight inequality, polarization, and the decline of

civic life. Crown.

Lenstra, N. (2018). Let’s move! Fitness programming in public libraries.

Public Library Quarterly, 37(1), 61-80. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2017.1316150

Lenstra, N., & McGehee, M. (2022). Public librarians and public

health: How do partners perceive them? Journal of Library Outreach and

Engagement, 2(1), 66-80. https://doi.org/10.21900/j.jloe.v2i1.883

Lenstra, N. & Roberts, J. (2022). South Carolina public libraries

& health: Needs and opportunities. https://libres.uncg.edu/ir/listing.aspx?id=37560

Liu, J., Tu-Keefner, F., Zamir, H., & Hastings, S. K. (2017). Social media as a tool connecting with library users in disasters: A

case study of the 2015 catastrophic flooding in South Carolina. Science

& Technology Libraries, 36(3), 274-287. https://doi.org/10.1080/0194262X.2017.1358128

Malone, T., & Clifton, S. (2021). Using focus groups to evaluate a

multiyear consumer health outreach collaboration. Journal of the Medical

Library Association, 109(4), 575-582. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2021.987

Mardis, M. A., Jones, F. R., Pickett, S. M., Gomez, D., Tenney, C. S.,

Leonarczyk, Z., & Nagy, S. (2020, October 13). Librarians as natural

disaster stress response facilitators: Building evidence for trauma-informed

library education and practice [Paper presentation]. 2020 Association of

Library and Information Science Educators Conference. http://hdl.handle.net/2142/108818

Mattern, S. C. (2007). The new downtown library: Designing with

communities. University of Minnesota Press.

Mon, L. (2021). The fight against Enzy: US libraries during the

influenza epidemic of 1918. DttP: Documents to the People, 49(1), 12-17.

https://doi.org/10.5860/dttp.v49i1.7538

Ogden, L. P., & Williams, R. D. (2022). Supporting patrons in crisis

through a social work-public library collaboration. Journal of Library

Administration, 62(5), 656-672. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2022.2083442

Oudshoorn, A., Van Berkum, A., Burkell, J., Berman, H., Carswell, J.,

& Van Loon, C. (2022). Supporting mental health in a public library

context: A mixed methods brief evaluation. Canadian Journal of Community

Mental Health, 41(2), 25-45. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2022-013

Pandolfelli, G., Hammock, A., Topek-Walker, L., D’Ambrosio, M., Tejada,

T., Della Ratta, C., LaSala, M. E., Koos, J. A., Lewis, V., & Benz Scott,

L. (2021). An interprofessional team-based experiential learning experience in

public libraries. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, 9(1), 54-63. https://doi.org/10.1177/23733799211048517

Pelczar, M., Frehill, L. M., Nielsen, E., Kaiser, A., & Li, J.

(2021). Public libraries survey: Fiscal year 2019. Institute of Museum

& Library Services. https://www.imls.gov/research-evaluation/data-collection/public-libraries-survey

Rubenstein, E. (2012). From social hygiene to consumer health:

Libraries, health information, and the American public from the late nineteenth

century to the 1980s. Library & Information History, 28(3),

202-219. https://doi.org/10.1179/1758348912Z.00000000016

Sandha, P., & Holben, D. H. (2021). Perceptions of the summer food

environment in a rural Appalachian Mississippi community by youth: Photovoice

and focus group. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition,

17(6), 834-849. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2021.1994082

Santos, M. C. (2021). Libraries as telehealth providers. Texas

Library Journal, 97(1), 92–94.

Smith, J. (2020). Information in crisis: Analyzing the future roles of

public libraries during and post-COVID-19. Journal of the Australian

Library and Information Association, 69(4), 422-429. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2020.1840719

State of Wisconsin. (2022, March 30). Gov. Evers announces $5 million

investment to expand access to telehealth services [Press release]. https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/WIGOV/bulletins/3110131

Tu-Keefner, F. (2016). The value of public libraries during a major

flooding. In A. Morishima, A. Rauber, & C. L. Liew (Eds.), Digital

libraries: Knowledge, information, and data in an open access society (pp.

10-15). Springer Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49304-6_2

Veil, S. R., & Bishop, B. W. (2014). Opportunities and challenges

for public libraries to enhance community resilience. Risk Analysis, 34(4),

721-734. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12130

Virginia Department of Health. (2021). Supporting testing access

through community collaboration. https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/coronavirus/protect-yourself/covid-19-testing/stacc/

Wahler, E. A., Ressler, J. D., Johnson, S. C., Rortvedt, C., Saecker,

T., Helling, J., Williams, M. A., & Hoover, D. (2022). Public library-based

social work field placements: Guidance for public libraries planning to become

a social work practicum site. Public Library Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2022.2044264

Whiteman, E. D., Dupuis, R., Morgan, A. U., D’Alonzo, B., Epstein, C.,

Klusaritz, H., & Cannuscio, C. C. (2018). Public libraries as partners for

health. Preventing Chronic Disease, 15. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.170392

Winkelstein, J. A. (2019). The role of public libraries in the lives of

LGBTQ+ youth experiencing homelessness. In B. Mehra (Ed.), LGBTQ+

librarianship in the 21st century: Emerging directions of advocacy and

community engagement in diverse information environments (pp. 197-221).

Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0065-283020190000045016

Wong, V., Cannuscio, C. C., Lowenstein, M., Feuerstein-Simon, R.,

Graves, R., & Meisel, Z. F. (2021). How do public libraries respond to

patron queries about opioid use disorder? A secret shopper study. Substance

Abuse, 42(4), 957–961. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2021.1900980

Woodson, D. E., Timm, D. F., & Jones, D. (2011). Teaching kids about

healthy lifestyles through stories and games: Partnering with public libraries

to reach local children. Journal of Hospital Librarianship, 11(1),

59-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/15323269.2011.538619

Appendix

Survey Instrument

|

Survey Questions |

Number of respondents |

|

Do

you understand the consent information provided above and agree to

participate in the study? |

|

|

Part 1. Demographics |

|

|

What is the zip code* where

your library is located? *Having this information

will allow us to incorporate data from other sources, including the US Census. |

142 |

|

What is the name of the library

or library branch where you work? |

142 |

|

What is your job title? |

142 |

|

How long have you worked at

your library? |

142 |

|

Part 2. Health

Services at the Library |

|

|

We would like to know how your

library supports health.

Please indicate what

types of health-related services or programs your library has, to your knowledge,

offered, as well as what types of topics you would

like to learn more about in the future. (Select all that apply) |

|

|

Access to health

information in general |

142 |

|

Access to health

literacy |

142 |

|

Access to

primary healthcare |

142 |

|

Access to

preventative health services |

142 |

|

Access to health

insurance |

142 |

|

Access to mental

health or behavioral health |

142 |

|

Access to

reproductive health |

142 |

|

Access to

services for substance use disorders |

142 |

|

Access to

COVID-19 related services |

142 |

|

Access to food |

142 |

|

Access to

nutrition |

142 |

|

Access to physical

activity |

142 |

|

Access to

support with chronic disease(s) |

142 |

|

Access to

services related to healthy aging |

142 |

|

Access to

reentry services for those previously incarcerated |

142 |

|

Access to

housing |

142 |

|

Access to

transportation |

142 |

|

Access to

employment |

142 |

|

Access to early

childhood services |

142 |

|

Access to

education (Adult) |

142 |

|

Access to

education (Pre-K) |

142 |

|

Access to

education (K-12) |

142 |

|

Access to legal

aid |

142 |

|

Access to

economic development opportunities |

142 |

|

Access to

technology |

142 |

|

Access to

literacy |

142 |

|

Part 3. Library in the

Community |

|

|

How would you rate the

following: [Options included Strongly agree, Slightly agree, Slightly

disagree, Strongly disagree] |

|

|

My library routinely

offers off-site programs or services |

136 |

|

Library staff

often participate in community meetings or coalitions |

136 |

|

Organizations in

general typically look to the library as a partner |

136 |

|

Health

organizations, specifically, look to the library as a partner |

136 |

|

Individuals in

the community typically see the library as a safe and trusted space to

access health literacy |

136 |

|

Individuals in

the community typically see the library as a safe and trusted space to

access health services |

136 |

|

My library sees

health equity as a priority |

136 |

|

My library

serves as a space where people can meet new people in

the community.. |

136 |

|

My library

serves as a space where social connections are affirmed |

136 |

|

Individuals in

the community typically see the library as a safe and trusted space for all

ages |

136 |

|

Individuals in

the community typically see the library as a safe and trusted space for all

ages |

136 |

|

Library staff

are typically well versed in the pressing issues facing the

community |

136 |

|

Library staff

are typically able to work collaboratively with other individuals and

organizations to address pressing community issues |

136 |

|

Part 4. The Library

and Community Health |

|

|

Have library staff and/or

partners ever offered any of the following at your library, or off-site with library

participation? (Select all that apply). "Partners"

here includes all individuals or organizations that are not directly affiliated with the library |

|

|

Immunization

clinics, in general (e.g. for vaccinations) |

129 |

|

Immunization

clinics, specifically for COVID19 |

129 |

|

COVID-19 testing |

129 |

|

Health screening

services: Blood pressure |

129 |

|

Health screening

services: Obesity |

129 |

|

Health screening

services: Mammography |

129 |

|

Health screening

services: other |

129 |

|

Assistance with

mental health issues (e.g. social, behavioral, emotional

needs) |

129 |

|

Referrals to

appropriate health and/or social service agencies |

129 |

|

Locating and evaluating free health information

online |

129 |

|

Using

subscription health database(s) |

129 |

|

Identifying

health insurance resources |

129 |

|

Understanding

specific health topics |

129 |

|

Identifying or

using local health resources |

129 |

|

Offering fitness

classes |

129 |

|

Offering

nutrition classes |

129 |

|

Summer meals |

129 |

|

Other ways of

distributing free food (community fridge, food boxes) |

129 |

|

Health fairs |

129 |

|

Farmer’s Markets |

129 |

|

Blood drives |

129 |

|

Food drives |

129 |

|

Mental health

first aid trainings |

129 |

|

Telehealth

services |

129 |

|

Have any of the following

health-related groups ever met at your library?

(Select all that apply) |

|

|

Health

coalitions |

127 |

|

Health

department task forces |

127 |

|

Area Agency on

Aging |

127 |

|

Other

health-related groups (please describe) |

127 |

|

None of the

above |

127 |

|

To your knowledge, have any of

the following ever occurred at your library, or on

property owned by your library (e.g. parking lot)? |

|

|

Drug overdose |

127 |

|

Drug deal |

127 |

|

Alcohol or

tobacco use against library policy |

127 |

|

Individuals

experiencing homelessness using library as de facto day

shelter |

127 |

|

Violence that

requires intervention from security staff or law enforcement |

127 |

|

Other health

related incidents (please describe) |

127 |

|

None of these |

127 |

|

Do any of your library staff

have access to the following on-site at your library?

(Select all that apply) |

|

|

Naloxone |

127 |

|

Epipen |

127 |

|

Automated

external defibrillator (AED) |

127 |

|

Other health-related

equipment (please describe) |

127 |

|

None of the

above |

127 |

|

Part 5. Staffing for

Health |

|

|

Does your library currently, or has your library ever had, any of the following

types of individuals available to the public? |

|

|

Social workers |

126 |

|

Social work

students |

126 |

|

Community health

workers |

126 |

|

Health educator |

126 |

|

Nurses |

126 |

|

AmeriCorps or

other volunteers |

126 |

|

Other

health-related professional (describe) |

126 |

|

If your library has any

health-related professionals currently available to the

public, about how often do these individuals typically provide services at your library? |

|

|

Daily |

126 |

|

Weekly |

126 |

|

Monthly |

126 |

|

Less than once a

month |

126 |

|

Not applicable |

126 |

|

If your library could have

any health-related professionals available to the

public, about how often do you think the services

of such individual(s) would be

needed at your library? |

|

|

Daily |

126 |

|

Weekly |

126 |

|

Monthly |

126 |

|

Less than once a

month |

126 |

|

Not applicable |

126 |

|

To your knowledge, does your

library have someone on staff who you would

characterize as a “champion” for health-related programs, services,

or partnerships? |

|

|

Yes |

126 |

|

No |

126 |

|

If yes, could you please

briefly describe what your library’s health champion(s)

do to support health-related programs, services, or partnerships? |

|

|

Part 6. Health

Partnerships and Funding |

|

|

Has your library ever worked

with or received funding from any of the following, specifically to offer health related

services or programs? |

|

|

SC Center for

Rural and Primary Healthcare |

123 |

|

Hands on Health

SC |

123 |

|

National Network

of Libraries of Medicine (NNLM) |

123 |

|

Institute of

Museum and Library Sciences |

123 |

|

Regional

healthcare systems |

123 |

|

Foundations |

123 |

|

Food Share SC |

123 |

|

South Carolina

State Library |

123 |

|

Clemson

Cooperative Extension |

123 |

|

Other

organizations (please describe) |

123 |

|

None of the

above |

123 |

|

Thinking about your local

community, how would you characterize the relationship

between your library and the following organizations? |

|

|

Health

department |

123 |

|

Hospital or

healthcare system(s) |

123 |

|

Health coalition

or alliances |

123 |

|

SNAP-Ed

implementing agency |

123 |

|

Local non-profit

organizations |

123 |

|

Colleges or

universities |

123 |

|

K-12 Schools |

123 |

|

Parks &

Recreation Unit |

123 |

|

Early education

providers, including daycares |

123 |

|

WIC Clinics |

123 |

|

Department of Justice

/ Department of Corrections |

123 |

|

Part 7. Health

Priorities |

|

|

What barriers, in your opinion,

stand in the way of your library being able

to participate in efforts to support health? (Select all that apply) |

|

|

No barriers |

122 |

|

Not sure where

to start |

122 |

|

No one has asked

us to help, or to participate in community efforts |

122 |

|

Funding |

122 |

|

Lack of

expertise on topic |

122 |

|

Lack of partners |

122 |

|

Lack of space |

122 |

|

Doesn't fit

within the mission of our library |

122 |

|

Other (please

specify) |

122 |

|

Thinking of future continuing

education opportunities, what are priorities

for you in terms of library support for health? (Select all that apply) |

|

|

How to get

started with health-related services or programs |

121 |

|

How to market

the availability of health-related services or programs |

121 |

|

How to sustain

health-related services or programs |

121 |

|

How to expand

health-related services or programs |

121 |

|

How to partner

with community collaborators |

121 |

|

How to evaluate

health-related services or programs |

121 |

|

Other (please

describe) |

121 |

|

None of the

above |

121 |

|

Thinking of future continuing

education opportunities, how would you most

like to learn more about the topics addressed in this questionnaire (select one) |

|

|

From a SC public

library worker who has directly worked on these topics at their

library |

122 |

|

From a SC public

library administrator who has supervised work on

these topics at their library |

122 |

|

From a medical

or health sciences librarian with expertise on this topic |

122 |

|

From a staff

member at the South Carolina Center for Rural and Primary

Healthcare |

122 |

|

From a person in

your community (e.g. local health department) |

122 |

|

From someone

else (please specify) |

122 |

|

Thinking about the topics

addressed in this questionnaire, is there anything else

you would like us to know? |

|

|

If you would be potentially

interested in participating in an interview or focus group

about these topics, please insert your email address here |

|

|

Please include your email

address to receive a $10 Amazon Gift Card |

|