Research Article

Exploring Library Activities, Learning Spaces, and Challenges Encountered Towards the Establishment of a Learning Commons

Maryjul T. Beneyat-Dulagan

Librarian

Cordillera State Institute

of Technical Education

(Baguio City School of Arts

and Trades)

Baguio City, Philippines

Email: djul351@gmail.com

David A. Cabonero

Faculty, School of Graduate

Studies

Saint Mary’s University

Bayombong, Nueva Vizcaya,

Philippines

Email: bluegemini7777@yahoo.com

Received: 6 May 2022 Accepted: 10 Oct. 2022

![]() 2023 Beneyat-Dulagan and Cabonero. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2023 Beneyat-Dulagan and Cabonero. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30164

Abstract

Objectives

–

This study was conducted to

determine the library activities, preferred learning spaces, and challenges

encountered by the students of Mountain Province State Polytechnic College

(MPSPC) Library, Philippines. Specifically, it sought to answer the following

problems: 1) What are the library activities of MPSPC students?; 2) What are

the preferred learning spaces in terms of a) physical environment and b)

virtual environment?; and 3) What are the challenges associated with library

learning activities encountered by the MPSPC students? The study then will be

used to explore the feasibility of proposing a learning commons.

Methods – This study used a

descriptive research method to determine the library activities, learning

spaces, and challenges encountered by MPSPC students in the Philippines. It

made use of a researcher-made survey questionnaire. Problem statement number 1

dealt with the library activities of MPSPC students. Problem statement number 2

dealt with the preferred learning spaces. Data were gathered from 500 graduate

and undergraduate students from a total of 3,015 enrolled during the first

semester of the SY 2019-2020 using a purposive random sampling technique.

Descriptive statistics such as frequency, percentage, and rank were used.

Results – The most frequent library learning activities

performed by the MPSPC students were doing assignments, using reference books,

searching/browsing printed materials, reviewing notes, and writing. Students’

least frequent library activities were surfing the web, using the computer,

using e-resources, eating while reading/writing, and sleeping. The most

preferred physical learning spaces were a makerspace, group study spaces, quiet

study rooms, and individual study spaces (individual study carrels), while the

most preferred virtual learning spaces were computer workstations, interactive

learning spaces, video viewing stations, and internet cafés. The overall

challenges encountered by MPSPC students were insufficient learning spaces,

poor internet connection, inability to find documents or books needed, lack of

reading area, lack of printing or photocopying service, lack of professional

books, and lack of e-resources. The least challenges encountered by MPSPC

students included very high library fees, poor ventilation, poor lighting

facility in the designated area, uncomfortable furniture, and lack of staff’s

kindness.

Conclusion – The MPSPC students perform

various educationally purposeful library activities, which are generally

engaging and support the library's mission. Students vary in their needs of

physical and virtual learning environments. Both of these learning spaces are

in demand among students, which are the key components of the learning commons.

Also, they specified the need for adequate learning spaces to support their

various library learning activities. The findings serve as the basis for

crafting a project proposal to establish a learning commons tailored to MPSPC

students’ library activities and preferred learning spaces, with consideration

for the challenges encountered by students, to support their learning and

academic success.

Introduction

A library is a place for nurturing the mind. It supports

learning, information, and research needs; thus, it is vital to students'

educational growth. In support of an institution's educational objectives to

meet its diverse learners' needs, libraries should provide a quiet and social

space for students’ various learning activities (Choy & Goh, 2016), a

healthy and safe environment for learning (Barton, 2018), and offer education

and relaxation (Waxman et al., 2007). Moreover, the library is a learning

environment characterized by abundant and rich information sources and

well-designed learning spaces. Within a library space, students identify

physical and virtual environments that help them achieve their learning goals.

Twenty-first century learners are connected to

digital technologies as their primary learning tools, but as global changes in

information occur, students’ learning activities are affected (McLeod, 2015).

The nature of tertiary education drastically changed as the 21st century

evolved and has impacted the nature of academic libraries (Turner et al.,

2013). Twenty-first century learning is often connected to an inquiry approach

in which students actively engage in their learning, accessing material and

scaffolding their knowledge to create rather than solely acquire information

(Stripling, 2008). The preferences of library users in library spaces can

change quickly and unpredictably (Gstalder, 2017), which affects library

support of the teaching and learning process (Roberts, 2007). In relation to

this, Turner et al. (2013) observed that new teaching and learning pedagogies

in higher education were influenced by social constructivist learning theories

and self-discovery practices. These theories supported that the most

significant learning takes place when individuals participate in social learning

activities (Matthews et al., 2011). As such, library users have high

expectations of quality academic facilities, such as the provision of library

spaces, library commons, and the like (Flaspohler, 2012).

How can a library position itself in these academic

environments? How can a library be responsive to the changing nature of

information access and the changing nature of users? There is a need for

rethinking the information and physical needs of students. Moreover, there is a

need for academic library innovation to better support the diverse learning

needs of students and accommodate students’ learning styles. Lankes (2016)

suggested that redesigning and conceptualizing the library is essential to the

21st century. He further stated that a move to a learning commons

approach is one tactic to meet users’ expectations. Roberts (2007) believed

that establishing a learning commons will support the teaching mission of an

institution. It would complement new teaching and learning pedagogies in higher

education which have shifted away from a teaching culture and toward a culture

of learning (Bennett, 2003).

Furthermore, libraries reinvent themselves as they

face new roles, such as making resources more accessible, connecting learners,

and constructing knowledge. Also, students do not just need information, they

need a place that encourages active involvement and motivates them. Learning

commons allow various learning activities (Holland, 2015), and help both

libraries and students remain current with modern demands and lifestyles.

With these paradigm shifts in libraries and

education, changes gradually occur with the library’s environment and ambiance.

In the Mountain Province State Polytechnic College (MPSPC) Library, not enough

areas serve the different learning needs of library users. A lack of technology

and facilities to help library users explore, create, and share knowledge has

been observed. Moreover, poor services have reduced both the number of users

and use of the library collection. Students’ needs and expectations affect all

aspects of their learning, specifically in the library. Diverse reading habits

and preferences of the students have been observed by the researchers as well.

The MPSPC Library has been accessible to all users

because it is almost centrally located on campus, but the reading area was not

enough to accommodate the students. Instead, students use the corridor as a

learning area since the reading room was insufficient. Students studying in the

corridor and even inside the room complained to the library staff because they

were distracted by students passing by. Students found it hard to study and

concentrate because of the noise. There were not enough individual study spaces

or group discussion rooms because the room was just a common space for every

user engaged in any activity. Based on observation by the researchers, the

problem was the slow internet connection, wherein students found it hard to

conduct research online, which caused some students to leave the library.

Faculty and school administrators noticed complaints about the insufficient

reading area and the misbehaviour of users. Hence, the plight of this academic

library encouraged the researchers to conduct this study.

Problems of the Study

This study was conducted

to determine the library activities, preferred learning spaces, and challenges

encountered by the students of MPSPC Library. Specifically, the study sought to

answer the following problems: 1) What are the library activities of MPSPC

students?; 2) What are the preferred learning spaces in terms of a) physical

environment and b) virtual environment?; and 3) What are the challenges

associated with library learning activities encountered by the MPSPC students?

Scope and Limitations of the Study

The study was

limited to one state college in the Philippines primarily to determine the

learning activities and spaces in the library and the challenges encountered by

the students, which served as the basis for establishing a learning commons.

This was conducted during the first semester of SY 2019-2020 and focused on 500

participants who were both undergraduate and graduate students.

Literature Review

In the

Philippines, some libraries are still traditional in giving services to their

users, resulting in a lack of social opportunities within the library. This

limits the opportunities for students to interact with each other in the

library spaces (McCunn & Gifford, 2015). This can be observed through the

image projected by the librarian, such as shushing students for speaking too

loudly, ringing a bell to remind them of their unruly behaviour, and the like.

With the new breed of library users, their diverse learning activities, habits,

styles, and needs are changing and should be addressed. This could be answered

by adopting a new library model such as the learning commons, which allows

students to enhance their social skills while researching, reading, and

learning. In establishing a model, there are imperative things to consider,

such as: 1) to identify the key priorities, such as which learning activities

occur in a successful learning commons (King, 2016); 2) to know the learning

activities of the users better to realize their needs (Spencer, 2007); 3) to

analyze the various activities, including which are most prevalent among

library users (Choy & Goh, 2016); 4) to understand the various learning

needs of students, such as learning activities, preferred learning spaces, and

challenges faced by students (Qayyum Ch. et al., 2017); and 5) to relate the various

activities of the students in the library to academic achievement (Paretta

& Catalano, 2013).

Implementing a

learning commons would primarily encourage students to use the library and

benefit from its services. However, this idea must be supported by asking the

right questions to students regarding their library activities, how they learn,

and their use of library services (Suarez, 2007). These learning activities and

study space preferences of library users relate to establishing a functional

learning commons. Thus, surveying students' library activities and preferred

learning spaces provides the evidence necessary to make effective decisions

about what facilities and equipment should meet their various needs (McCrary,

2017).

The learning

spaces model furthers the mission of the learning commons by providing various

formal and informal flexible learning spaces that facilitate better learning

(Turner et al., 2013), and these physical and virtual learning spaces can

impact learning (Oblinger, 2006). It can bring people together to encourage

exploration, collaboration, and discussions. These spaces should be flexible

and networked, bringing together formal and informal activities in an

environment that acknowledges that learning can occur anywhere, at any time, in

either physical or virtual spaces. The physical and virtual environments

provide students with a comfortable place to relax, learn, and create

(Cicchetti, 2015). Moreover, spatial designs influence students' learning

activities, and the relevance of spatial designs that encourage and support

dynamic, engaged, and inspired learning is a fundamental feature of the

learning spaces (Roberts, 2007). The impact of spaces becomes more prominent as

higher education pedagogical practices move from the traditional to a more

flexible, student-centred approach. Evolving learning spaces convey a new image

of the library, marking a new direction in library and educational philosophies

(Somerville & Harlan, 2008).

The development

of learning spaces supports innovative pedagogical approaches and environments

that promote student engagement in the learning process (Elkington & Bligh,

2019). How and why users have different preferences in learning spaces depends

on their individual needs and styles. Moreover, there are advantages to student

learning in providing a range of spaces. Various collaborative and independent

spaces promote self-directed learning (Keating & Gabb, 2005). Non-quiet

spaces in the library, such as group study and flexible learning spaces, are

ideal for many library users (Freeman, 2005).

A learning

commons consists of physical and virtual environments designed for learning.

The centre for student learning fosters creativity, encourages patron use of

space, offers new technologies, and uses space creatively to encourage

inquiry-based thinking (Mihailidis & Diggs, 2010). It is a space designed

for collaboration and access to information and other tools, such as electronic

resources. Here, students will be empowered as they take part in the learning commons,

which will lead to more learning and better preparation for their careers.

Students’ involvement in the learning commons produces a better student success

rate (Khan, 2020), and students learn best when they are allowed to learn in an

environment that is both welcoming and supportive (Holeton, 2020).

A clear

understanding of how the learning commons benefits students is also the

foundation for a successful transition (Cicchetti, 2015). Libraries need to

remain relevant and support learning in new ways. Libraries recognize that,

because of the Internet and Web 2.0 applications, students have new powers and

abilities that facilitate independent access to information (Watstein &

Mitchell, 2006). Blummer and Kenton (2017) mentioned that learning commons has

no standard definition. Yet, learning commons represent academic library spaces

that provide computer and library resources and a range of academic services

that support learners and learning. Turner et al. (2013) argued that designers

of learning commons readily understand that learners are not merely information

consumers. Instead, they actively participate with information to create

meaningful knowledge and wisdom.

As society

continues to experience a pedagogical shift in learning, students should be

given more opportunities to make connections, collaborate, communicate, think

critically, and be creative. Learning in a learning commons environment is

purposeful, authentic, active, and student-centred (McCunn & Gifford,

2015). There have been numerous studies on learning commons, one of which

performed surveys on their own users’ needs (Yebowaah & Plockey, 2017).

Students’ various learning activities have to be considered in order to provide

appropriate learning spaces (Brown-Sica et al., 2010). Rawal (2014) asserted

that:

Like

Bandura’s (1977) idea of “reciprocal determinism,” where the interactions among

environmental, cognitive, and behavioral influences create the synergy to

affect how one behaves in a specific context, so does the reciprocity among the

physical, virtual, and socio-cultural aspects of a learning commons affect how

students learn within a commons. A truly holistic learning commons is a nexus

for negotiating ideas and producing new knowledge. It is that bustling bazaar

where knowledge, discoveries, and innovations are born, nurtured, and set forth

to impact the rest of the world. (p. 67)

Our review of

the literature revealed that our study is unique as it dwells on library

activities and preferred learning spaces among students in the Philippines.

Hence, this study will be used to explore a learning commons as one of the new

features of our library. Barton (2018) mentioned that the learning commons

model is geared to understand and identify learning needs in accordance with

the learning activities, preferences, and challenges of library users.

Methods

This study utilized a descriptive method of research to determine the

library activities, learning spaces, and challenges encountered by MPSPC

students in the Philippines. It made use of a researcher-made survey

questionnaire. Problem number 1 dealt with the library activities of MPSPC

students and was based on the study of Cabfilan (2012). Problem number 2 dealt

with the preferred learning spaces and was adopted from the study of Peterson

(2013). However, it has been modified to suit the research design by

contextualizing the items in the MPSPC Library. The survey questionnaire is

composed of three parts, namely: 1) the different library activities of MPSPC

students, 2) the preferred learning spaces, and 3) the challenges encountered

by the respondents relative to learning activities within the library. This

questionnaire underwent face and content validity by three library and

information science professors and one research professor at Saint Mary’s

University (Philippines).

Data were gathered from 500 graduate and undergraduate students from

3,015 enrolled during the first semester of the SY 2019-2020, from August to

December 2019 at MPSPC, Bontoc Campus (Table 1), using a purposive random

sampling technique. In gathering the needed data, the following procedures were

undertaken: 1) A permission letter was sent to the MPSPC President to seek

approval for the conduct of the study for the students enrolled in the various

programs; 2) The letter was addressed to the President through the Deans of

undergraduate and graduate studies; 3) Upon seeking approval, a letter was

submitted to the Director of MPSPC-Registrar for the number of enrollees in the

various programs to identify the number of students in each program; 4) The

questionnaire was administered to the students who were visiting the library

voluntarily. One of the researcher’s colleagues helped administer the

questionnaire; 5) An informed consent letter was attached to the questionnaire.

The respondents did not receive any payment for their participation nor any

reimbursements. Participants had the right to refuse to continue, with any

information already provided not used in the study. It was emphasized to them

the assurance of the confidentiality of their answers; 6) The questionnaires

were immediately retrieved and checked if all items were answered; and 7)

Questionnaires were submitted to the statistician. Descriptive statistics such

as frequency, percentage, and rank were used.

Table 1

Respondents of

the Study

|

Course/Department |

No. of Enrollees |

No. of Respondents (n) |

|

Bachelor of Science and

Criminology |

1,244 |

206 |

|

Bachelor of Science in

Nursing |

213 |

35 |

|

Bachelor of Science and

Information Technology |

123 |

20 |

|

Bachelor of Science Office

Administration |

75 |

12 |

|

Bachelor of Arts in

Political Science |

41 |

7 |

|

Bachelor of Science in

Business Administration |

170 |

28 |

|

Bachelor of Science in

Accountancy |

158 |

26 |

|

Bachelor of Secondary

Education |

400 |

66 |

|

Bachelor of Elementary

Education |

233 |

39 |

|

Bachelor for Early Childhood

Education |

9 |

2 |

|

Bachelor of Special Needs Education |

13 |

3 |

|

Graduate School |

174 |

29 |

|

Bachelor of Science in

Tourism Bachelor of Science in

Tourism Management Bachelor of Science in Hotel

and Tourism Management Bachelor of Science in

Hospitality Management Associate of Arts in Hotel

and Restaurant Management |

162 |

27 |

|

Total |

3,015 |

500 |

Results and Discussion

The Library Activities of Students

This study

refers to the various activities performed by diverse students in the library.

These learning activities are purposeful and aim to improve behaviour,

information, knowledge, understanding, attitude, values, or skills (Table 2).

This includes different types of learning, such as self-learning and others,

and learning could be formal or informal (Eurostat, 2016).

The preferred

activities done in the library were doing

assignments, using reference books, searching or browsing printed materials,

reviewing notes, writing research works, reading (periodical/ fiction books/

non-fiction books), studying in a group, and studying alone on my books or materials. These activities were all

academic-related, supporting the fact that the library is the first place to

get information as it houses universal knowledge (Bailin, 2011). This indicates

that libraries significantly impact students’ academic achievements (Khan,

2020; Sriram & Rajev, 2014). It could be attributed to the availability of

resources when doing their assignments. Also, students go to the library to

search or browse printed materials and eventually use reference books, which

suggests that materials in the library are useful and relevant.

Table 2

The Library

Activities of Students

|

Activities |

n |

% |

Rank |

|

Doing

assignments |

455 |

91.0 |

1 |

|

Using

reference books |

396 |

79.2 |

2 |

|

Searching/ Browsing printed

materials |

385 |

77.0 |

3 |

|

Reviewing notes |

384 |

76.8 |

4 |

|

Writing (research works) |

369 |

73.8 |

5 |

|

Reading (periodical/ fiction

books/ non-fiction books) |

362 |

72.4 |

6 |

|

Studying

in a group |

345 |

69.0 |

7 |

|

Studying alone on my own

books/ materials |

324 |

64.8 |

8 |

|

Sitting comfortably while reflecting |

316 |

63.2 |

9 |

|

Interacting with librarians/

Getting help from staff members |

314 |

62.8 |

10 |

|

Listening to music while

studying/ reading/writing |

290 |

58.0 |

11 |

|

Surfing the web |

270 |

54.0 |

12 |

|

Using computer |

265 |

53.0 |

13 |

|

Using

e-resources |

255 |

51.0 |

14 |

|

Eating

while reading/ writing |

168 |

33.6 |

15 |

|

Others: Sleeping |

35 |

7.0 |

16 |

This coincides

with Iroaganachi and Ilogho (2012), who found that

students use reference materials frequently, which can be attributed to the

orientation program designed for students. On the other hand, listening to

music while studying, reading, or writing; using e-resources; using computers;

surfing the web; and eating

while reading or writing were the least common activities done in

the library. Also, eating while reading or writing was ranked 15th,

which means that some students do not favor the library policy that food and

drink are prohibited inside. However, some MPSPC students prefer a place to

study while having a snack, and this could be observed in some libraries

allowing them to bring food and drinks. This finding corroborates the idea in

21st-century learning wherein libraries are innovating to meet the demands of

these learners, in which food and drink are welcomed in the libraries (Roberts,

2007).

Also, it is

worthwhile to mention that 35 respondents wrote sleeping as one of their library activities. This connotes that the

library is not just a place to study but a place that provides relaxation to

students (Waxman et al., 2007).

However, it is

very surprising to note that learning activities relating to computer

technology, such as surfing the web, using computers, and using e-resources were ranked 12th, 13th, and 14th, respectively.

Seemingly, students do not prefer using information technology to satisfy their

library information needs, thus resulting in minimal utilization of e-resources

(Yebowaah & Plockey, 2017). This contradicts the findings of Martin (2008),

that students use technology frequently thus changing the learning environment

of higher education. This suggests that a slow internet connection would make

students dissatisfied with using computers and resources and make it

challenging to research online.

The Preferred Learning Spaces

According to

Head (2016), there are appropriate library designs for learning spaces, and

they should be different in every library since it is in accordance with the

learning activities and preferences of every library user. It was further

pointed out by Bieraugel and Neill (2017) that designing library spaces is

imperative for the different intended needs, activities, preferences, and

styles of library users. Also, Choy and Goh (2016) reiterated that the design

of spaces in support of learning is far more complex as a variety of users’

activities and styles need to be considered.

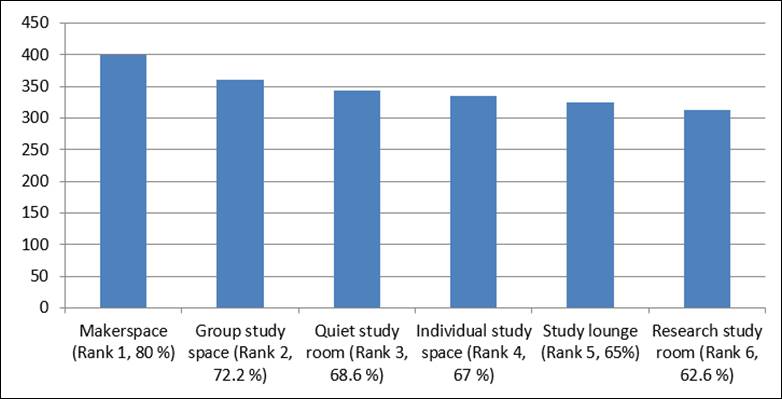

Figure 1

Preferred

learning spaces in physical environment.

In this study,

the most preferred learning spaces in terms of physical environment were makerspace, group study spaces, quiet study rooms, and individual study spaces, respectively,

as shown in Figure 1. Makerspace was

the most prevalent, which infers that learning is best acquired through

hands-on activities. Group study space

was second, which assumes that students may feel they can learn better in

groups. This indicates that noise should be welcomed and considered in the

group study area within the library (Mohanty, 2002). Meanwhile, study lounge was ranked 5th as the

preferred learning space, implying that there are students who prefer working

while socializing as well (Waxman et al., 2007). Undeniably, some students

expect the library to offer space not only for scholarly pursuits but also for

socializing (Paretta & Catalano, 2013). However, some students still prefer

individual study spaces/ individual study

carrels and quiet study rooms.

Seemingly, they prefer to learn best in silence and do not like being disturbed

when they are studying (Arenson, 2013).

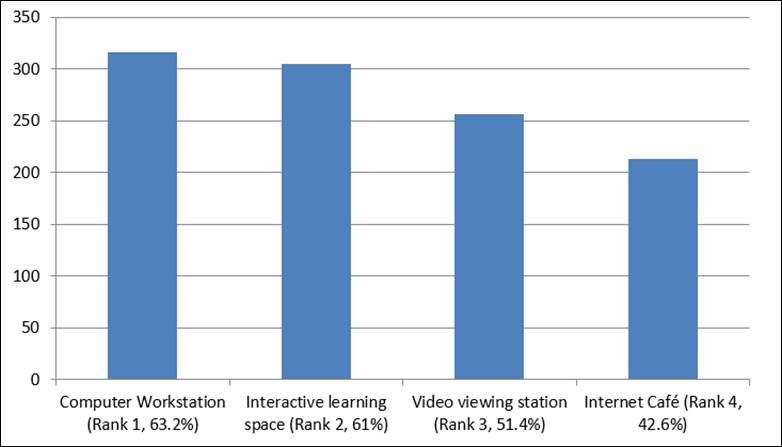

Figure 2

Preferred

learning spaces in virtual environment.

The most preferred learning spaces in the virtual

environment were computer workstations,

interactive learning spaces, video viewing stations, and internet cafés, respectively (Figure 2).

The computer workstation is the most preferred learning space in terms of the

virtual environment. This implies that activities which demand computer are

prevalent among the students. As mentioned by Singh and Wadhwa (2006), computers

are an excellent learning tool. This signifies that 63% of library users prefer

to work individually in a computer workstation, while others prefer working in

an interactive learning space.

It is interesting to note that interactive learning space was ranked 2nd, which implies that

students want spaces that encourage them to study independently through

technology. This finding supports the idea that learning is engaging, and

engagement is expected to increase students’ learning outcomes (Vercellotti, 2018).

This preference for interactive learning space implies that students have

varied learning styles, and, in this case, it requires the use of technology

for them to learn better.

Also, the video

viewing station was ranked 3rd, which implies that there are students who

are both visual and auditory learners who prefer watching and listening in some

areas of the library. As mentioned by Alawani et al. (2016), students still

prefer video technologies that boost their learning experience. However, internet

café ranked last, implying that few students prefer learning while having

coffee or snacks. Seemingly, this idea is not yet practiced by the students and

the library. Perhaps their traditional beliefs of eating inside the library are

not accepted as the standard norm. As mentioned, 21st-century libraries should

meet the needs of these learners, thus allowing them to eat while learning in

the library (Holland, 2015).

As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the physical and virtual environments were

rated as learning space preferences among students, which are the key

components of a learning commons (Pressley, 2017). The findings show that

students demand such spaces in accordance with their learning activities in the

library.

Challenges Encountered by the MPSPC Students

McMullen (2008) described a learning commons as a

“dynamic place that encourages learning through inquiry, collaboration,

discussion, and consultation.” (p. 1). She further asserted that it is

necessary to understand the activities engaged by students. The learning

commons is not just a concept but a place for learning in the library (Roberts,

2007). These learning commons have been created to support the teaching

missions of the respective parent institutions. Academic institutions support

this model because faculty and administration recognize that students learn in

dynamic and various ways. McCrary (2017) supported the need to develop a

learning commons since the library is not just a place to store books and study

but rather a place where meaning and learning emerge from access to knowledge.

However, its implementation can also be hampered by challenges, which are

listed in Table 3.

Table 3

Challenges Encountered by the MPSPC Students

Relative to Their Library Learning Activities

|

Areas |

Challenges |

n |

% |

Rank |

|

Physical

Facilities |

Insufficient

learning spaces for various activities |

319 |

63.8 |

1 |

|

Services |

Poor

internet connection |

262 |

52.4 |

2 |

|

Services |

Inability

to find documents/ books needed |

231 |

46.2 |

3 |

|

Physical

Facilities |

Lack

of reading area/ Reading area is not enough |

209 |

41.8 |

4 |

|

Services |

Lack

of printing or photocopying services |

208 |

41.6 |

5 |

|

Library

Collection |

Lack

of professional books |

207 |

41.4 |

6 |

|

Library

Collection |

Lack

of e-resources |

206 |

41.2 |

7 |

|

Physical

Facilities |

Lack

of toilet facilities |

166 |

33.2 |

8 |

|

Physical

Facilities |

Lack

of installed security equipment |

149 |

29.8 |

9 |

|

Financial

Resources |

Lack

of support /budget is not enough to sustain library projects or programs |

142 |

28.4 |

10 |

|

Human

Resources |

Lack

of support staff |

135 |

27 |

11 |

|

Human

Resources |

Limited

number of professional librarians |

124 |

24.8 |

12 |

|

Financial

Resources |

Very

high library fee |

118 |

23.6 |

13 |

|

Physical

Facilities |

Poor

ventilation |

113 |

22.6 |

14 |

|

Physical

Facilities |

Poor

lighting facility in the designated reading areas |

112 |

22.4 |

15 |

|

Physical

Facilities |

Uncomfortable

furniture |

110 |

22 |

16 |

|

Services |

Lack

of staff’s kindness |

109 |

21.8 |

17 |

Among the physical facilities, insufficient learning spaces for various activities (ranked 1st,

with 63.8% in agreement) and lack of

reading area or reading area is not enough (ranked 4th, with 41.8% in

agreement) were challenges encountered by the MPSPC students. Students

have various activities, but not all spaces can accommodate these activities.

Libraries should be well designed to accommodate students' learning

requirements and enhance their learning outcomes and satisfaction (Li et al.,

2018). Furthermore, the result corroborates with the study of Bailin (2011)

that students demand ample space for reading, especially when they flock to the

library. Indeed, Ranganathan’s 5th law states that the library is a growing

organism (Barner, 2011). As collections continuously increase, the physical

spaces also widen to accommodate more library users and eventually maximize the

use of the collections, thus making the library a growing institution of

learning.

The least challenges encountered on physical

facilities were lack of toilet facilities, lack of installed security

equipment, poor ventilation, poor lighting facility in the designated reading

area, and uncomfortable

furniture. In relation to the findings on preferred learning spaces,

these challenges reported by the respondents might impact group study spaces, study

lounges, individual study spaces/

individual study carrels, and quiet

study rooms. Poor ventilation has great impact on students’ learning, and

this was supported by Haverinen-Shaughnessy and Shaughnessy (2015), who found

that students did not perform well in a poorly ventilated environment. Also,

inadequate lighting in the library is not suitable for students and would

affect students’ performance. The findings also imply that there are students seeking

comfort while learning (McDonald, 2011). Hence, librarians and administrators

should make libraries more comfortable for students (Mohanty, 2002). The lack of installed security equipment (ranked

9th) can also be attributed to non-return of items by borrowers and theft of

library materials (Maidabino & Zainab, 2011). Thus, it is necessary to

provide security equipment in the library to ensure longevity, availability,

and effective provision of services to users.

Table 3 revealed that among the top five challenges

encountered by the MPSPC students, three were reported that emerge from

challenges encountered relative to library services, namely: 1) poor internet connection (52.4%, ranked

2nd), 2) inability to find documents or

books needed (46.2%, ranked 3rd), and

3) lack of printing/ photocopying services (41.6%, ranked

5th). Poor internet connection is

quite noticeable because students frankly complain about the internet

connection in the library. This shows that there are MPSPC students who are

internet users, and they surf the net since information is easily available

(Shrestha, 2008). Thus, students prefer using the internet, as compared with

printed materials, because it provides information readily at all times. The

internet also gives faster access to information as well as offers a large

amount of information (Kumah, 2015). As mentioned by Yebowaah (2018), the use

of internet among students has a positive influence on their academic

performance. Also, the MPSPC students ranked 3rd the inability to find documents or books needed (46.2%). This shows

that students are not aware of how materials are organized in the library. This

can be attributed either to students’ unfamiliarity with the services or how

the materials are organized (Hughes, 2010). Lack

of printing/photocopying services was

also in the top five challenges encountered (41.6%, ranked 5th). This suggests

the need for photocopying services to save time in taking down notes from books

in the library. Materials in the library often copied by students are of more

rare materials that tend not to be available in book shops for sale. Sriram and

Rajev (2014) mentioned that libraries must provide various services such as

photocopying to enable users to utilize the library collections at greater potentials.

On the other hand, the lack of staff’s

kindness (21.8%, ranked 17th) was

ranked last among the challenges encountered by the students, which shows that

librarians are approachable and accommodating.

Under human resources, lack of support staff (27%, ranked 11th) as one of the challenges

encountered by students suggests the need for support staff. Students do not

just deal with librarians every time they visit the library, but also

paraprofessionals serving them (Guion, 2012). This implies that support staff

have to undergo seminars on how to manage library patrons. The limited number of professional librarians

(24.8%, ranked 12th) can be either attributed to a lack of professional

librarian positions (with appropriate title, salary, and benefits) or a lack of

licensed librarians. Tanhueco-Tumapon (2017) reiterated that librarians should

be given an academic status (that is, like any teaching or research faculty

member), wherein there is a corresponding increase in salary and therefore is

due an academic rank provided they have a master’s degree. Having an academic

status in higher education leads them to be motivated in doing their functions

as dignified librarians, since librarians and paraprofessionals may have

different service standards.

For the library collection, lack of professional books and lack

of e-resources were the challenges encountered by students. This implies

that the collections of both books and e-resources were perceived to be

insufficient. To address this, the library should build partnerships among

other academic libraries to strengthen its collection (Munro & Philps,

2008) and increase its budget to purchase more collections.

In terms of financial resources, lack of

support/budget is not enough to sustain library projects or programs

(28.4%, ranked 10th), and very high library fees (23.6%, ranked 13th)

were the perceived challenges encountered by the students. State colleges and

universities in the Philippines collect fewer library fees than in private

schools. This may be why it is ranked almost at the bottom. Although these

challenges were at the bottom, the budget is essential in realizing library

programs and projects, such as establishing or improving a library space. It

could mean that increasing library fees would make students expect that the

library can satisfy their needs and demands.

Recommendations

The library

should support the various learning activities of students, which include doing

assignments, using reference books, searching/browsing printed materials,

reviewing notes, writing, and others. It should design functional and flexible

learning spaces tailored to the students’ ideal needs, such as their learning

activities. Thus, the study suggests strong recommendations to provide various

learning spaces such as a makerspace, group study spaces, quiet study rooms,

individual study spaces, computer workstations, interactive learning spaces,

video viewing stations, and an internet café within the library premises to

cater to the diverse students with various learning preferences and learning

activities.

To continue

building literature and knowledge in this area, it is recommended to conduct

further research to include: 1) other areas such as policies, budgeting, and

linkages; 2) categories of users such as faculty, alumni, and visitors; and 3)

statistical tools such as using correlations, factor analysis, and others.

Conclusion

A learning

commons is a place to culture the mind wherein student learning encourages

creativity, promotes social learning, enhances new information technology

skills, and stimulates inquiry-based thinking. It is a space to nurture

students’ minds for collaboration, learning, and interaction through a

welcoming and supportive environment.

The MPSPC

students perform various educationally purposeful library activities. The

activities among the students are generally engaging and support the library's

mission. Students vary in their needs of physical and virtual learning

environments. Both of these types of learning spaces

are in demand among students, which are the key components of the learning

commons. Also, students specified the need for adequate learning spaces to

support their various library learning activities. Thus, the findings serve as

the basis for crafting a project proposal to establish a learning commons

tailored to MPSPC students’ library activities and preferred learning spaces,

with consideration for the challenges encountered by students, to support their

learning and academic success.

Author Contributions

Mrs. Maryjul T. Beneyat-Dulagan:

Conceptualization (equal), Data curation, Formal analysis (lead), Investigation

(equal), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing

(equal) Mr. David A. Cabonero: Conceptualization (equal), Formal

analysis (supporting), Investigation (equal), Visualization, Writing – original

draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (equal)

References

Alawani, A.

A., Senteni, A., & Singh, A. D. (2016).

An

investigation about the usage and impact of digital video for learning. In J.

Novotná & A. Jančařík (Eds.), Proceedings

of the 15th European Conference on e-Learning: ECEL 2016 (pp.

1–9). Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited.

Arenson, M.

(2013). The impact of a student-designed

learning commons on student perceptions and use of the high school library.

Retrieved from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/THE-IMPACT-OF-A-STUDENT-DESIGNED-LEARNING-COMMONS-Arenson/83e55c93e23d913fca7565cdb210e40411c5019e

Bailin, K.

(2011). Changes in academic library space: A case study at the University of

New South Wales. Australian Academic

& Research Libraries, 42(4), 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2011.10722245

Barner, K. (2011). The library is a

growing organism: Ranganathan's fifth law of library science and the academic

library in the digital era" (2011). Library

Philosophy and Practice (e-journal), 548. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/548

Barton, C.

(2018). Transforming an academic library

to a learning commons model: Strategies for success [Doctoral dissertation,

Concordia University Irvine]. CUI Digital Repository. http://hdl.handle.net/11414/3385

Bennett, S.

(2003). Libraries designed for learning.

Council on Library and Information Resources. https://www.clir.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/pub122web.pdf

Bieraugel, M.,

& Neill, S. (2017). Ascending Bloom's pyramid: Fostering student creativity

and innovation in academic library spaces. College

& Research Libraries, 78(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.78.1.35

Blummer, B.,

& Kenton, J. M. (2017). Learning commons in academic libraries: Discussing

themes in the literature from 2001 to the present. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 23(4), 329–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2017.1366925

Brown-Sica, M.,

Sobel, K., & Rogers, E. (2010). Participatory action research in learning

commons design planning. New Library

World, 111(7/8), 302–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074801011059939

Cabfilan, N.

(2012). Customers’ satisfaction on the

circulation, reference, online and instruction services at Benguet State

University Main Library [Master’s thesis, Saint Mary’s University

(Philippines)].

Choy, F. C.,

& Goh, S. N. (2016). A framework for planning academic library spaces. Library Management, 37(1/2), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-01-2016-0001

Cicchetti, R. (2015).

Transitioning a high school library to a learning commons: Avoiding the tragedy

of the commons [Doctoral dissertation, Northeastern University]. Northeastern University Library

Digital Repository Service. https://doi.org/10.17760/D20193587

Elkington, S.,

& Bligh, B. (2019). Future learning

spaces: Space, technology and pedagogy. Advance

HE. https://telearn.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02266834

Eurostat.

(2016). Classification of learning

activities (CLA): Manual. https://doi.org/10.2785/874604

Flaspohler, M.

(2012). Engaging first-year students in

meaningful library research: A practical guide for teaching faculty. Chandos.

Freeman, G.

T. (2005). The library as place: Changes

in learning patterns, collections, technology, and use. Council on Library

and Information Resources. http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/publ129/freeman.html

Gstalder, S. H.

(2017). Understanding library space

planning [Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania]. University of

Pennsylvania Libraries ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI10289537/

Guion, D. (2012,

March 14). Library staff: The paraprofessional. Reading, Writing, Research. https://www.allpurposeguru.com/2012/03/library-staff-the-paraprofessional/

Haverinen-Shaughnessy,

U., & Shaughnessy, R. J. (2015). Effects of classroom ventilation rate and

temperature on students’ test scores. PLoS

ONE 10(8), e0136165. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136165

Head, A. J.

(2016). Planning and designing academic

library learning spaces: Expert perspectives of architects, librarians, and

library consultants. Project Information Literacy Research Institute. https://projectinfolit.org/publications/library-space-study/

Holeton, R.

(2020). Toward Inclusive

Learning Spaces: Physiological, Cognitive, and Cultural Inclusion and the

Learning Space Rating System. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/2/toward-inclusive-learning-spaces

Holland, B.

(2015, January 14). 21st-century libraries: The learning commons. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/blog/21st-century-libraries-learning-commons-beth-holland

Hughes, H.

(2010). International students’ experiences of university libraries and

librarians. Australian Academic &

Research Libraries, 41. https://doi:10.1080/00048623.2010.10721446

Iroaganachi, M. A., & Ilogho, J. E. (2012). Utilization of reference books by

students: A case study of Covenant University, Nigeria. Chinese Librarianship: An International Electronic Journal, 34,

48–56. http://www.white-clouds.com/iclc/cliej/cl34II.pdf

Keating,

S., & Gabb, R. (2005). Putting learning into the learning commons: A

literature review. Post-compulsory Education Centre, Victoria University. https://vuir.vu.edu.au/id/eprint/94

Khan, S.

(2020). Impact

of learning spaces on student success. Retrieved from https://www.edtechreview.in/trends-insights/insights/impact-of-learning-spaces-on-student-success/

King,

J. G. (2016). Extended and experimenting: Library learning commons service

strategy and sustainability. Library

Management, 37(4/5), 265–274. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-04-2016-0028

Kumah,

C. H. (2015). A comparative study of use of the library and the internet as

sources of information by graduate students in the University of Ghana. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal).

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1298/

Lankes, R. D.

(2016). Expect more: Demanding better libraries for today's complex world (2nd ed.). http://dx.doi.org/10.26153/tsw/13962

Li, L. H., Wu,

F., & Su, B. (2018). Impacts of library space on learning

satisfaction – An empirical study of university library design in Guangzhou,

China. The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 44(6), 724–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2018.10.003

Maidabino, A. A., & Zainab, A. N. (2011). Collection

security management at university libraries: Assessment of its implementation

status. Malaysian Journal of Library

& Information Science, 16(1), 15–33. https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1301/1301.5385.pdf

Martin, A. (2008). Digital literacy and the “digital

society.” In C. Lankshear, & M. Knobel (Eds.), Digital literacies: Concepts, policies, and practices (pp.

151–176). Peter Lang.

Matthews, K. E.,

Andrews, V., & Adams, P. (2011). Social learning spaces and student

engagement. Higher Education Research and

Development, 30(2), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.512629

McCrary, Q. D.

(2017). Small library research: Using qualitative and user-oriented research to

transform a traditional library into an information commons. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 12(1), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8863F

McCunn, L. J.,

& Gifford, R. (2015). Teachers’ reactions to learning commons in secondary

schools. Journal of Library

Administration, 55(6), 435–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2015.1054760

McDonald, C. A. (2011). The library transformed into learning

commons: A look at the library of the future [Master’s thesis, University

of Central Missouri]. James C. Kirkpatrick Library Digital Repository. https://ucmo.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/view/delivery/01UCMO_INST/1284617640005571

McLeod, S.

(2015). “It’s not just about signing out

books!”: From library to library learning commons: A catalyst for change

[Master’s thesis, University of Victoria]. UVicSpace. http://hdl.handle.net/1828/6315

McMullen, S.

(2008). US academic libraries: Today's

learning commons model (PEB Exchange 2008/04). Organisation for Economic Co-operation

and Development. https://www.oecd.org/unitedstates/40051347.pdf

Mihailidis, P., & Diggs, V.

(2010). From information reserve to media literacy learning commons: Revisiting

the 21st century library as the home for media literacy education. Public Library Quarterly, 29(4),

279–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2010.525389

Mohanty, S. (2002). Physical comfort in library study

environments: Observations in three undergraduate settings [Master’s

thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill]. Carolina Digital

Repository. https://doi.org/10.17615/mne6-v039

Munro, B., &

Philps, P. (2008). A collection of importance: The role of selection in

academic libraries. Australian Academic

& Research Libraries, 39(3), 149–170. http://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2008.10721347

Oblinger, D. G. (Ed.). (2006). Learning spaces. EDUCAUSE. https://www.educause.edu/research-and-publications/books/learning-spaces

Paretta, L. T.,

& Catalano, A. (2013). What students really

do in the library: An observational study. The

Reference Librarian, 54(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2013.755033

Peterson, N. K.

(2013). The developing role of the

university library as a student learning center: Implications to the interior

spaces within [Master’s thesis, Iowa State University]. Iowa State

University Digital Repository. https://doi.org/10.31274/etd-180810-3678

Pressley, L.

(2017). Charting a clear course: A state of the state of the learning commons.

In D. M. Mueller (Ed.), At the helm:

Leading transformation: The proceedings of the ACRL 2017 Conference, March

22–25, 2017, Baltimore, Maryland (pp. 112–119). Association of College and

Research Libraries. https://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2017/ChartingaClearCourse.pdf

Qayyum Ch., A.,

Hina, Q. A., & Abid, U. (2017). An empirical investigation of problems and

issues being faced by the students while using the libraries in University of

the Punjab, Lahore. Bulletin of Education

and Research, 39(2), 225–238. http://pu.edu.pk/images/journal/ier/PDF-FILES/17_39_2_17.pdf

Rawal, J.

(2014). Libraries of the future: Learning

commons: A case study of a state university in California [Master’s thesis,

Humboldt State University]. The California State University ScholarWorks. http://hdl.handle.net/10211.3/134872

Roberts, R. L. (2007). The evolving

landscape of the learning commons. Library

Review, 56(9), 803–810. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242530710831257

Shrestha, N. (2008). A study on student’s use of library

resources and self-efficacy [Master’s thesis, Tribhuvan University]. E-LIS.

http://eprints.rclis.org/22623/

Singh, S., & Wadhwa, J. (2006).

Impact of computer workstation design on health of the users. Journal of Human Ecology, 20(3),

165–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2006.11905922

Somerville, M.

M., & Harlan, S. (2008). From Information Commons to Learning Commons and

learning spaces: An evolutionary context. In B. Schader (Ed.), Learning commons: Evolution and

collaborative essentials (pp. 1–36). Chandos.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-84334-312-7.50001-1

Spencer, M. E.

(2007). The state-of-the-art: NCSU Libraries Learning Commons. Reference Services Review, 35(2),

310–321. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00907320710749218

Sriram, B.,

& Rajev, M. K. G. (2014). Impact of academic library services on user

satisfaction: Case study of Sur University College, Sultanate of Oman. DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information

Technology, 34(2), 140–146. https://publications.drdo.gov.in/ojs/index.php/djlit/article/view/4499

Stripling, B.

(2008). Inquiry: Inquiring minds want to know. School Library Media Activities Monthly, 25(1), 50–52. https://www.teachingbooks.net/content/InquiringMindsWantToKnow-Stripling.pdf

Suarez, D.

(2007). What students do when they study in the library: Using ethnographic

methods to observe student behavior. Electronic

Journal of Academic and Special Librarianship, 8(3). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ejasljournal/83/

Tanhueco-Tumapon,

T. (2017, August 18). 21st-century

academic libraries. The Manila Times. https://www.manilatimes.net/2017/08/18/opinion/analysis/21st-century-academic-libraries/345157/

Turner, A.,

Welch, B., & Reynolds, S. (2013). Learning spaces in academic libraries – A

review of the evolving trends. Australian

Academic and Research Libraries, 44(4), 226–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2013.857383

Vercellotti, M. L. (2018). Do

interactive learning spaces increase student achievement? A comparison of

classroom context. Active Learning in

Higher Education, 19(3), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417735606

Watstein, S. B.,

& Mitchell, E. (2006). Do libraries matter? Reference Services Review, 34(2), 181–184. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320610669416

Waxman, L.,

Clemons, S., Banning, J., & McKelfresh, D. (2007). The library as place:

Providing students with opportunities for socialization, relaxation, and

restoration. New Library World, 108(9/10),

424–434. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074800710823953

Yebowaah,

F. A., & Plockey, F. D. D. (2017). Awareness and use of electronic

resources in university libraries: A case study of University for Development

Studies Library. Library Philosophy and

Practice (e-journal). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1562/

Yebowaah, F. A.

(2018). Internet use and its effect on senior

high school students in Wa Municipality of Ghana. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1817

Appendix

Research

Instrument

Dear

Respondents,

A pleasant day!

The undersigned

is presently engaged in gathering data for her research entitled “Exploring

Library Activities, Learning Spaces, and Challenges Encountered Towards the

Establishment of a Learning Commons” as a requirement for the Degree Master in

Library and Information Science.

In line with

this, the researcher earnestly requests you to be one of the respondents of the

research study. The researcher assures that your answers will be dealt with

utmost confidentiality.

Thank you and

God bless!

Sincerely yours,

Researchers

Name (Optional):

____________________

Course/Year:

_______________________

1.

The following are the library activities

performed by students in the library. Put a check mark (√) to all that applies to you.

|

Doing assignments |

|

|

Eating while reading/writing |

|

|

Interacting with librarians/

Getting help from staff members |

|

|

Listening to music while

studying/reading/writing |

|

|

Reading (periodical/fiction books/non-fiction

books) |

|

|

Searching/ Browsing printed

materials |

|

|

Sitting comfortably while

reflecting |

|

|

Studying alone on my own

books/materials |

|

|

Studying in a group |

|

|

Surfing the web |

|

|

Using computer |

|

|

Using electronic resources |

|

|

Using reference books |

|

|

Writing (research works) |

|

|

Reviewing notes |

|

|

Others (Pls. specify) |

|

2.

Which of the following is your favorite

place to study or learn at the library? [You may check (√) one or more].

2.1.

PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT

|

Group study space - a space where you can

talk with friends while studying |

|

|

Individual study space

(Individual study carrels) - a

cubicle, stall, enclosed area for individual to read and study |

|

|

Makerspace -a

space where you can create hands-on projects in groups or individually |

|

|

Quiet study room - a

private, very quiet workspace |

|

|

Research study room -a

room assigned for individual for research and other scholarly activities that

requires extensive use of library materials |

|

|

Study lounge - an

area open for students for gathering, studying and

relaxing |

|

2.2

VIRTUAL ENVIRONMENT

|

Computer

workstation - an area consist of computer that is connected to a network for

individual use |

|

|

Internet

café - an area where there is

convenient access to coffee that offers internet access on its own computers

or desktops |

|

|

Interactive

learning space -a space provided for

individual or group user/s for school work that needs computer technology |

|

|

Video

viewing station -an area that is highly

equipped with computer for watching specifically for educational purposes |

|

3.

Put a check mark (√) on the challenges you encountered in the library. [You may check

one or more].

|

|

|

Limited number of

professional librarian |

|

|

Lack of support staff |

|

|

Others (pls. specify) |

|

|

|

|

Poor lighting facility in

the designated reading areas |

|

|

Poor ventilation |

|

|

Lack of toilet facilities |

|

|

Lack of installed security

equipment |

|

|

Insufficient learning spaces

for various activities |

|

|

Uncomfortable furniture |

|

|

Lack of reading area/

Reading area is not enough |

|

|

Others (pls. specify) |

|

|

|

|

Very high library fee |

|

|

Lack of support /budget is

not enough to sustain library projects or programs |

|

|

Others (pls. specify) |

|

|

|

|

Lack of professional books |

|

|

Lack of e-resources |

|

|

Others (pls. specify) |

|

|

|

|

Inability to find documents/

books needed |

|

|

Lack of staff’s kindness |

|

|

Lack of printing or

photocopying services |

|

|

Poor internet connection |

|

|

Others (pls. specify) |

|