Research Article

Changes in the Library Landscape

Regarding Visible Minority Librarians in Canada

Yanli Li

Business and Economics

Librarian

Wilfrid Laurier University

Library

Waterloo, Ontario, Canada

Email: yli@wlu.ca

Maha Kumaran

Librarian

Education and Music Library

University of Saskatchewan

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

Email: Maha.Kumaran@usask.ca

Allan Cho

Community Engagement Librarian

(Program Services)

University of British Columbia

Library

Vancouver, British Columbia,

Canada

Email: allan.cho@ubc.ca

Valentina Ly

Research Librarian

University of Ottawa Library

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Email: vly@uottawa.ca

Suzanne Fernando

Senior Services Specialist

Toronto Public Library

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Email: sfernando@tpl.ca

Michael David Miller

Associate Librarian &

Liaison Librarian for French Literature, Economics and Gender Studies

McGill University Library

Montréal, Québec, Canada

Email: michael.david.miller@mcgill.ca

Received: 16 Apr. 2022 Accepted: 25 July 2022

![]() 2022 Li, Kumaran, Cho, Ly, Fernando, &

Miller.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2022 Li, Kumaran, Cho, Ly, Fernando, &

Miller.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30151

Abstract

Objective

–

As a follow-up to the first 2013 survey,

the Visible Minority Librarians of Canada (ViMLoC)

network conducted its second comprehensive survey in 2021. The 2021 survey gathered

detailed information about the demography, education, and employment of visible minority librarians (VMLs)

working in Canadian

institutions. Data from the 2021 survey and the analysis presented in

this paper help us better understand the current library landscape, presented

alongside findings from the 2013 survey. The research results will be helpful

for professional associations and library administrators to develop initiatives

to support VMLs.

Methods

–

Researchers

created

online survey questionnaires using Qualtrics XM in English and translated them

into French. We distributed the survey invitation through relevant library

association electronic mail lists and posted on ViMLoC’s

website, social networking platforms, and through their electronic mail list.

The survey asked if the participant was a visible minority librarian. If the response

was “No,” the survey closed. Respondents indicating "Yes" were asked

36 personal and professional questions of three types: multiple-choice, yes/no,

and open-ended questions.

Results

–

One

hundred and sixty-two VMLs completed the 2021 survey. Chinese remained the

largest ethnic identity, but their proportion in the survey decreased from 36%

in 2013 to 24% in 2021. 65% were aged between 26 and 45 years old. More than

half received their library degree during the 2010s. 89% completed their library

degree in Canada, a 5% increase from 2013. The majority of

librarians had graduated from University of Toronto (25%), followed closely by

University of British Columbia (23%), and Western University (22%). Only 3%

received their library degree from a library school outside North America. 34%

of librarians earned a second master’s degree and 5% had a PhD. 60% of

librarians had less than 11 years of experience. Nearly half worked in academic

libraries. Most were located in Ontario and British

Columbia. 69% of librarians were in non-management positions with 5% being

senior administrators. 25% reported a salary above $100,000. In terms of job

categories, the largest group worked in Reference/Information Services (45%),

followed by Instruction Services (32%), and as Liaison Librarians (31%). Those

working in Acquisitions/Collection Development saw the biggest jump from 1% in

2013 to 28% in 2021. 58% of librarians sought mentoring support, of whom 54%

participated in formal mentorship programs, and 48% had a visible minority

mentor.

Conclusion

– 35% more VMLs responded to

the 2021 survey compared to the 2013 survey. Changes occurred in ethnic

identity, generation, where VMLs earned a Master of Library and Information

Science (MLIS) or equivalent degree, library type, geographic location, and job

responsibilities. The 2021 survey also explored other aspects of the VMLs not covered

in the 2013 survey, such as librarian experience, salary, management positions,

and mentorship experience. The findings suggested that the professional

associations and library administrators would need collaborative efforts to

support VMLs.

Introduction

For decades there has been an awareness and recognition that the library

workforce does not reflect the diversity of the population in Canada (CAPAL,

2019; Jennings & Kinzer, 2022). The Visible Minority Librarians of Canada (ViMLoC) network formed in December 2011 to connect, engage,

and support racialized librarians in the country (ViMLoC,

n.d.). In 2013, on behalf of ViMLoC, Maha Kumaran and Heather Cai (2015) conducted the first

survey of its kind (referred to as the “2013 survey”) to gather statistical information

on Canadian visible minority librarians (VMLs). The 2013 survey assessed VMLs'

educational qualifications and employment details to help identify their needs,

challenges, and barriers within the profession. Besides this foundational

survey, there remains very little information of this kind on racialized

librarians across different institutions in Canada. When implementing the 2013

survey, ViMLoC had planned to repeat its survey to

better understand the changes in the library workforce over time. As such, the

authors designed and administered a redux survey in English and in French

between January and March 2021 (referred to as the “2021 survey”). The 2021

survey investigated two aspects: 1) similar demographic questions as the

previous survey; and 2) additional questions that sought to explore the

experiences of VMLs in the workplace.

This paper focuses on the results from 162 respondents of the 2021 survey

and compares results, where applicable, to the 2013 survey (Kumaran & Cai,

2015). For questions that are not covered in the 2013 survey, findings will be

compared to other studies as appropriate. This research will help VMLs

understand how their position in the library landscape has changed over the

years. Recommendations provided will help professional associations and library

administrators continue to develop initiatives to advocate for VMLs, which in

turn will contribute to the promotion of equity, diversity, and inclusion

(EDI).

Literature Review

The literature review for this article focuses on many topics in

librarianship such as racial diversity, lack of minorities in leadership

positions, salary inconsistencies, and mentorship. While the major focus of the literature

review is from a Canadian context, some papers from the United States are cited

to provide a broader context for racial diversity in librarianship. In the

literature, the terms “visible minority librarians”, “librarians of colour”, “racialized librarians”, and “ethnic minority

librarians” are one of many terms to refer to the population of interest (Kandiuk, 2014; Kumaran, 2012; Kumaran & Cai, 2015; Kung

et al., 2020). A scarcity of professional literature on and

by VMLs in a Canadian context continues to persist, even years after the

initial ViMLoC study, with a notable absence of

publications in French.

Demographics

The data on racialized library professionals has been sparse for much of

the history of Canadian libraries, although it has gradually increased. Kumaran

and Cai’s (2015) “Identifying the

Visible Minority Librarians in Canada: A National Survey” is one of the

most comprehensive studies of diversity in Canadian libraries. More research

from census surveys has been released since then. The Canadian Association of

Professional Academic Librarians (CAPAL) conducted censuses in 2016 and 2018.

Though limited to academic libraries in Canada, the CAPAL censuses built a

comprehensive demographic picture of the profession of academic librarianship

by collecting data about librarians working in colleges and university

libraries. In 2021, the Canadian Association of Research Libraries (CARL)

(n.d.) released a Diversity and Inclusion Survey to gather baseline data on the

composition of personnel in 21 CARL libraries, to gauge employee feedback on

current EDI initiatives, and to establish a set of benchmarks against which to

evaluate and measure the impact of their EDI strategies and practices.

Recruitment and Retention

Beyond just the demographics of diverse librarians in the field is an

emerging body of literature about diversity within the scope of racism in

libraries. In Kung, Fraser, and Winn’s (2020) systematic review, the authors

found that despite a number of approaches used to

recruit minorities in academic libraries, the number of visible minorities in

the field has remained stagnant for decades. Their research indicated an

established body of literature that defined diversity, with race, ethnicity,

gender, and class identified as the most frequently used dimensions. The

authors found an increased number of publications on diversity in librarianship

in the 2000s, drawing more attention to the topic over the past twenty years

than prior to that time. In particular, residencies,

internships, and mentorship were the major interventions for recruitment and

retention, but residency programs existed in an American context, and not so

much within the Canadian context. The papers analyzed in the study mostly

focused on recruitment and retention for early career librarians, but less so

about advancement of more senior librarians.

Leadership

Although the literature is somewhat limited, there are three areas to

highlight from the literature that relate to our paper: leadership, mentorship,

and salary. The recently published CARL Diversity Census and Inclusion Survey

revealed that racialized library staff were underrepresented in senior leader

and other managerial roles (CCDI, 2022). Kumaran’s (2012) Leadership in Libraries focused on ethnic-minority librarians and

is one of the more comprehensive texts targeting strategies for success.

Written primarily for first-generation immigrant librarians, Kumaran explored

the major cultural differences affecting leadership from mainly Asian and

African cultures in the context of White mainstream libraries, including

cultural adaptation and language issues. Hines’ (2019) research focused on

academic librarians and further explored how current leadership development

opportunities reinforced the existing biased structures within libraries. Using

the lens of critical race theory, Hines offered tools to better describe and

understand the problems so that they could be addressed meaningfully, chiefly

through a restructuring of both the mechanics and the curriculum of leadership

development training.

Salaries

Salary has been understudied for library professionals in Canada, not to

mention for VMLs. While CAPAL’s 2016 and 2018 censuses of academic librarians

gathered visible minority status, ethnic identity, and salary information,

their summary reports did not include any analysis of the relationship between

salary and race (CAPAL, 2016; CAPAL, 2019). The survey conducted by the

Canadian Association of University Teachers (2019) provided average academic

librarian salaries by gender, age, region, and institution, but not by race.

The 8Rs Practitioner Survey in 2014 had microdata on salary and visible

minority status for CARL librarians (Delong et al., 2015a). Using a subset of

those microdata, Li (2021) used multiple regression models to study

demographic, job, and labour market factors that

affected CARL librarians’ salaries. A significant pay gap was identified

between VMLs and non-VMLs.

Mentorship

Mentorship has proven to be one of the most significant factors

contributing to a librarian’s career success in Canada (Harrington &

Marshall, 2014; Law, 2001; Oud, 2008). Mentoring can be provided in formal and

informal formats (Damasco & Hodges, 2012;

Mackinnon & Shepley, 2014). Particularly, for VMLs who face challenges

entering the Canadian job market and adapting to the workplace climate and

culture, getting mentoring support is essential (Kandiuk,

2014; Kumaran & Cai, 2015). Kung, Fraser, and Winn (2020) found that

mentorship was used at academic libraries for retention of VMLs, but there was

an overall lack of focus on mid- to late- career VMLs.

As mentioned in Kumaran & Cai’s (2015) study, this absence of

professional literature by minority librarians could have many causes:

[librarians] are in positions that do not require them to

publish; lack of training in writing academic papers, especially if they are

first generation minority librarians; lack of support for writing for

publication; lack of time or funding; not having a dedicated minority-focused

Canadian library journal that allows them to voice their thoughts; and perhaps

fear of bringing attention to themselves” (p.111)

Being in a position that does not require publication is particularly true

for Quebec academic librarians in Francophone colleges and universities where

they do not yet hold academic status or an equivalent/parallel to academic

status. This does not mean discussions like these are not happening in French;

they simply are not being distributed via professional and academic

publications. There is also a gap in the literature where librarians are not

writing about minority librarians. Based on data from the 2021 survey focusing

on VMLs, this research will contribute to filling the gap. A future study on

the motivations for such lack of writing could be extremely beneficial to the

current body of Canadian minority librarian research.

Methods

Building on the 12 questions from the 2013 survey, wording for seven of the

original questions was updated for clarity or to reflect changes to the

profession, and 24 additional questions were added to the 2021 survey. An

online survey questionnaire was created using Qualtrics XM (see Appendix). The

entire survey was sent to the 2021 survey research team and ViMLoC

committee members for a pilot test before they were released to the target

audience. After ethics approvals from the authors’ respective institutions, the

English language survey was made available between January 21, 2021 and

February 28, 2021. It was a nation-wide survey with participation from VMLs

working in Canadian institutions. The online survey invitation was sent to VMLs

through relevant library association electronic mail lists, such as CARL,

CAPAL, and provincial library associations. The invitation was also posted on ViMLoC’s website, three social networking platforms

(Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn), and through their electronic mail list. When

the English survey was distributed, the research team received inquiries about

the availability of a French version of the survey. To help get information

from French racialized minority librarians and to fill the gap in the work of ViMLoC, the research team decided to do a French version.

One team member translated the English survey to French and circulated it

amongst Québecois library associations and other

networks between March 1, 2021 and March 31, 2021.

The 2021 survey provided a definition of visible minorities from the

Canadian Employment Equity Act: “Persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who

are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour”

(Government of Canada, 2021). The

participants were asked to identify if they were a visible minority librarian.

If the response was “No,” the survey closed. The rest of the survey consisted

of personal and professional questions of three types: multiple-choice, yes/no,

and open-ended. Specifically, there were six questions about demographic

information, 10 questions about education, and 20 questions about employment.

For details of the questionnaire, see the Appendix. For the

purpose of this research, we analyzed microdata on these librarians. We

conducted cross-tabulation and chi-square analyses for in-depth examinations of

the relationships between some variables, including employment type and career

stage, type of mentorship and perceptions of the helpfulness of mentorship in

librarians’ career development, and the visible minority status of mentors and

perceptions of their helpfulness for mentees.

Results and Discussion

Of the 294 librarians that attempted the 2021 survey, 162 respondents who

identified themselves as VMLs were permitted to complete it, representing a 35%

increase from the 120 participants in the 2013 survey. There were 138

librarians who completed the English survey and 24 who completed the French

survey.

Demography

The questions in this section focused on ethnic identity, generation

status, disability status, gender, and age.

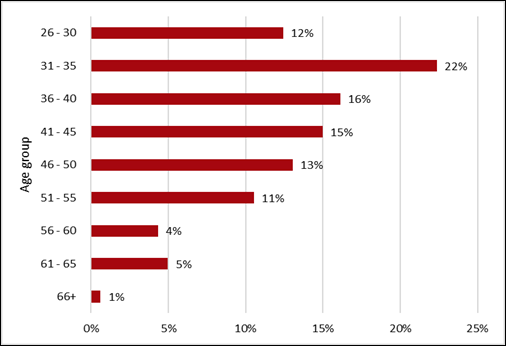

Ethnic Identity

Respondents were asked to self-identify their ethnic

group. Without accounting for mixed races, the largest ethnic identity

represented among the 159 respondents was Chinese (24%, n=38), compared to 36%

(n=43) in the 2013 survey, followed by South Asian (15%, n=24), and Black (12%,

n=19) (Figure 1). The percentage of Black librarians remained unchanged between

the two surveys at 12%. The proportions of Latin American, Korean, Filipino,

Southeast Asian, and Arab librarians increased slightly, whereas those of South

Asian, West Asian, and Japanese librarians decreased slightly. In 2021 there

were 13% (n=21) respondents that identified as a mixture of White and visible

minorities and 9% (n=14) that identified as multiple visible minorities.

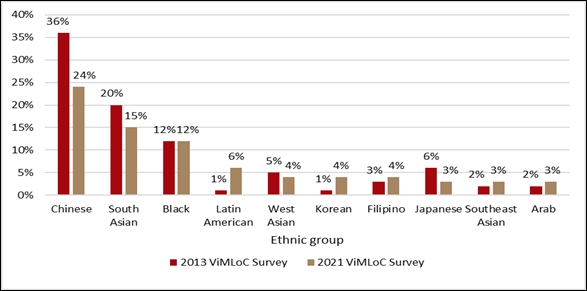

Generation Status

Participants were asked about their generation status in Canada. First

generation visible minorities refer to those who were born elsewhere and moved

to Canada at some point during their lives. Second generation visible

minorities are those who were born in Canada to one or more immigrant parents.

Third generation or more refers to visible minorities who were born in Canada,

with both parents who were also born in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2021). As

shown in Figure 2, of the 157 respondents in the 2021 survey, 56% (n=88)

identified themselves as first generation, compared to 63% (n=76) in 2013

(Kumaran & Cai, 2015, p.113). 40% (n=63) identified themselves as second

generation, compared to 28% (n=33) from the 2013 survey (28%, n=33). The

portion of third generation or more librarians was 4% (n=6) in 2021 versus 9%

(n=11) in 2013.

Figure 1

Ethnic identity.

Figure 2

Generation status.

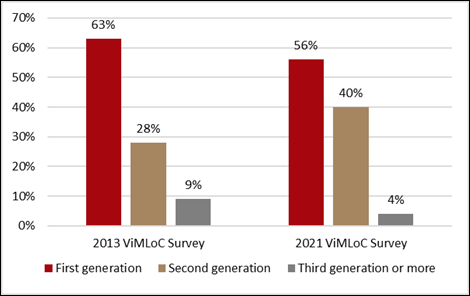

Disability Status, Gender, and Age

Of the 159 respondents in the 2021 survey, 8% (n=12) identified themselves

as a person with a disability. Ten respondents provided details of their

disability conditions that included physical and mental disabilities, and

chronic illnesses. Librarians were predominantly female (81%, n=130) with 16%

(n=25) males, and nearly 4% (n=6) had other gender identifications or preferred

not to answer. As shown in Figure 3, those aged 31-35 accounted for 22% (n=36),

followed by 36-40 (16%, n=26), 41-45 (15%, n=25), and 46-50 (13%, n=21). Only

10% (n=16) were over the age of 55, which suggested that the respondents were

younger than the overall visible minority workforce, of which 15% were over the

age of 55 (Statistics Canada, 2017).

Figure 3

Age group.

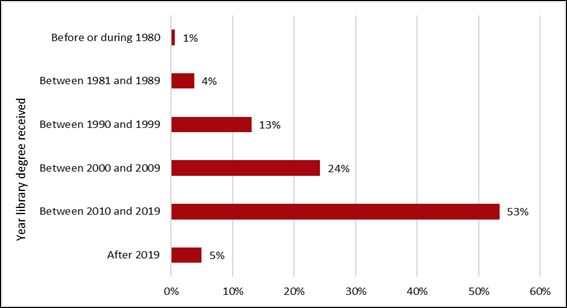

Education

Library Degree

The questions in this section focused on when and where

participants received their professional library degree – Master of Library

& Information Science (MLIS) or equivalent – and whether

or not it was American Library Association (ALA) accredited. Figure 4

shows that more than half (53%, n=86) received their library degree during the

2010s, doubling the percentage of those receiving their library degree during

the 2000s (24%, n=39). Seven librarians received their degree before the 1990s

and eight librarians received it after 2019.

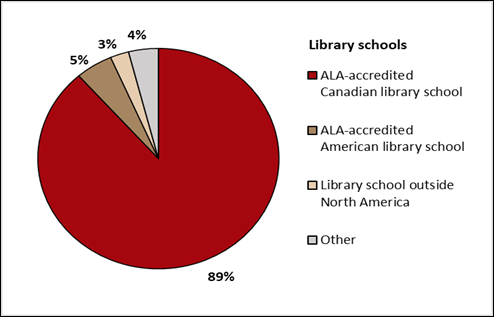

When asked where they completed their library degree, 89%

(n=142) of the 160 respondents indicated “from an ALA-accredited Canadian

library school,” as compared to 84% (n=101) in 2013 (Kumaran & Cai, 2015,

p.113). 5% (n=8) received their library degree from an ALA-accredited American

library school. Only 3% (n=4) mentioned getting their library professional

degrees from outside North America (Figure 5). This small proportion could be

because ALA accreditation has been an impediment for librarians with foreign

credentials (Taleban, 2016). Many immigrant

librarians received an additional library degree through an ALA-accredited

program after moving to Canada.

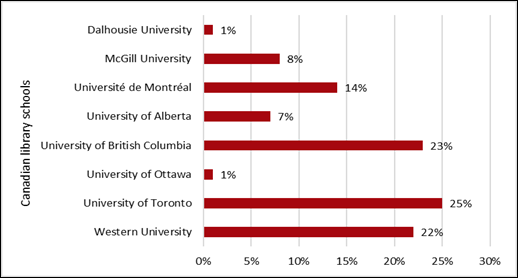

For the 142 respondents who completed their library

degree in Canada, they were asked to indicate the university that granted their

library degree. The top three institutions were the University of Toronto (25%,

n=35), the University of British Columbia (23%, n=32), and Western University

(22%, n=31) (Figure 6). In comparison, in the 2013 survey, of the 101

respondents, about 15% received their library degree from the University of

Toronto, almost 40% from the University of British Columbia, and 31% from

Western University (Kumaran & Cai, 2015, p.113). It is worth noting that

14% (n=20) of the respondents graduated from Université de Montréal. This data

was not collected in 2013 when the survey was not conducted in French.

Seventeen respondents provided the name of the country

outside of Canada where they received their library education. Almost half (n=8)

indicated the United States; other countries mentioned included Brazil, France,

Ghana, India, Iran, Singapore, and the United Kingdom. Of the nine respondents

who had an international non-ALA accredited library degree, four stated that

their degree was recognized for their current employment at public or academic

libraries, whereas the other five had different experiences. Two librarians

felt compelled to complete a Canadian MLIS degree to secure a job; another

received a library technician diploma in Canada and ended up with librarian

status after years of doing non-librarian jobs. The other two did not get their

foreign degree recognized and were working in a non-library setting or in a

position relying more on their non-librarian experience and skills.

Figure 4

Year library degree was received.

Figure 5

Where library degree was received.

Figure 6

University where library degree was received.

Additional Education

In addition to an MLIS degree, the respondents have attained professional

degrees, additional certificates, diplomas, or advanced degrees. In Table 1, of

the 152 respondents, 21% (n=32) earned professional degrees, and 34% (n=51) had

their second master’s degree. This finding was close to the CARL’s 8Rs Redux

Survey which reported 32% with a second master’s (Delong et al., 2015b, p.100)

but lower than 57% in the 2018 CAPAL Census (CAPAL, 2019, p.45). 2% (n=3) of

the respondents in the 2021 survey reported having a third Master’s degree, as

compared to 3% in the 2018 CAPAL Census. 5% (n=8) held a PhD which was in line

with the CARL’s 8Rs Redux Survey result but much lower than nearly 11% among

academic librarians in the 2018 CAPAL Census. 38% (n=58) indicated they had

additional degrees, certificates or diplomas,

specifically 34 bachelor’s degrees, 25 certificates, seven diplomas, and 10

other education attainments. These research results suggested evidence of a

trend of increasing professional and graduate education among librarians. This

may be attributable to an increased demand for librarians to perform specialist

roles that require additional credentials after they have entered the librarian

profession. As revealed in Ferguson (2016), 26% of the 800 academic library job

postings preferred a second advanced degree and 7% required one. The most

frequent functional areas asking for advanced subject knowledge were subject

specialists. Librarians pursuing additional education may also be due to

personal interest or the possibility of support from their current institutions

with funds and time for studying. It is also possible that some VMLs have

earned non-MLIS degrees in their home country before pursuing librarianship in

Canada, or that they feel the need to upgrade themselves with additional

qualifications to sustain their professional positions here in Canada.

Table 1

Non-MLIS Education Attained

|

Education |

Count |

Percentage |

|

Professional degree |

32 |

21% |

|

Second master’s degree |

51 |

34% |

|

Third master’s degree |

3 |

2% |

|

PhD |

8 |

5% |

|

Additional degrees, certificates, or diplomas |

58 |

38% |

Employment

The questions in this section focused on librarian experience, library

type, geographic distribution, type of employment, leadership positions,

salary, job categories, and mentorship experience. The librarians were also

surveyed about their experiences in workplaces such as microaggressions and job

satisfaction. These questions deserve an in-depth study and will be published

in a separate paper.

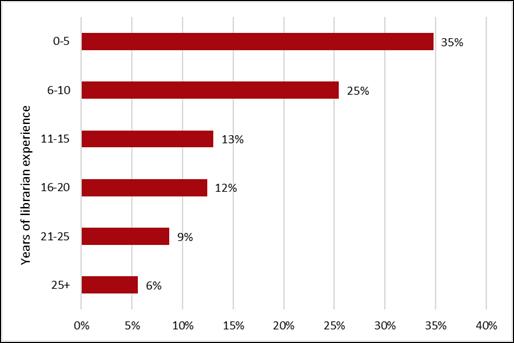

Librarian Experience

Librarians with less than six years of experience made up 35% (n=56),

followed by 6-10 years (25%, n=41), 11-15 years (13%, n=21), 16-20 years (12%,

n=20), and 21-25 years of experience (9%, n=14). 6% (n=9) have been a librarian

for more than 25 years (Figure 7).

Figure 7

Librarian experience.

Library Type

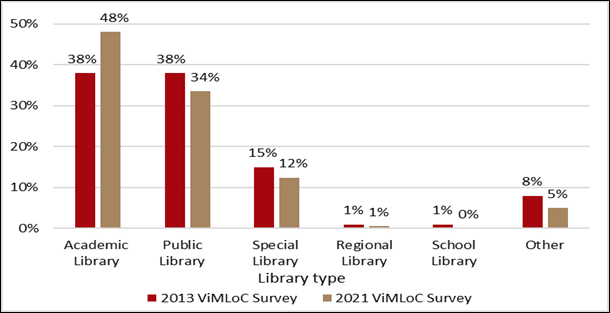

From 2013 to 2021, the most noticeable change was the increase of

respondents working in academic libraries. As shown in Figure 8, 48% (n=78) of

VMLs in the 2021 survey identified themselves as working in academic libraries,

compared to 38% (n=45) in the 2013 survey. Conversely, the spread of

respondents employed at public, special, and school libraries was lower than

previously captured. The increase of respondents from academic libraries could

be due to the retirement wave hitting academic librarianship. The CARL 8Rs 2014

Practitioner Survey revealed that 34% of all CARL librarians expected to retire

within the next 10 years (Delong et al., 2015b, p.47). Many studies have

examined succession planning at Canadian academic libraries when bracing the

reality of baby boomer librarians retiring (Guise, 2015; Harrington &

Marshall, 2014; Popowich, 2011). Kumaran (2015)

pointed out the importance of including VMLs in the succession planning

process. Another explanation for the increased academic librarian participation

could be due to the more effective application of policies towards EDI in

universities in recent years. In addition to having general employment equity

policies in place, some universities have set goals to increase hiring of

visible minority staff (University of Victoria, 2015). As an example of

professional library associations, CARL (2020) has realized the significance of

EDI in academic libraries and published a guide to aid recruitment and

retention of diverse talent. In such contexts, visible minorities may have more

opportunities to enter academic librarianship compared to nearly a decade ago.

It is noteworthy that studies on librarian turnover at non-academic libraries

are very limited. Further research is needed to explore how employment of VMLs

has changed at those libraries and how that change may have affected employment

at academic libraries.

Figure 8

Employment by library type.

Geographic Distribution

As in the 2013 survey, VMLs were widely spread across

Canada, with respondents from Prince Edward Island and Yukon participating in

the 2021 survey (Table 2). A vast majority of respondents continued to be in

British Columbia and Ontario; however, British Columbia comprised 22% (n=35) of

these employed librarians, compared to 40% (n=48) in 2013, whereas respondents

from Ontario accounted for 45% (n=72) in 2021 versus 27% (n=32) in 2013. Due to

adding a French iteration of the survey in 2021, librarians in Quebec made up

14% (n=22), compared to only 4% (n=5) in 2013. The geographic distribution of

VMLs reflected similar patterns of visible minority populations across Canada.

The 2016 Census data showed that Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec were the

top three most populous provinces for visible minorities (Statistics Canada,

2018b).

Table 2

Geographic Distribution

|

Province or Territory |

2013 ViMLoC Survey |

2021 ViMLoC Survey |

|

Alberta |

8% (n=10) |

7% (n=11) |

|

British Columbia |

40% (n=48) |

22% (n=35) |

|

Manitoba |

6% (n=7) |

2% (n=3) |

|

New Brunswick |

2% (n=2) |

1% (n=1) |

|

Newfoundland and Labrador |

1% (n=1) |

1% (n=2) |

|

Nova Scotia |

5% (n=6) |

3% (n=4) |

|

Nunavut |

1% (n=1) |

0% (n=0) |

|

Ontario |

27% (n=32) |

45% (n=72) |

|

Prince Edward Island |

0% (n=0) |

1% (n=1) |

|

Quebec |

4% (n=5) |

14% (n=22) |

|

Saskatchewan |

6% (n=7) |

3% (n=4) |

|

Yukon |

0% (n=0) |

2% (n=3) |

Type of Employment

In 2021, an overwhelming 85% (n=137) of respondents were working in

permanent positions and 11% (n=18) were in temporary positions (e.g., contract,

limited-term). A larger proportion of librarians were

working full-time (30 or more hours/week) (90%, n=143 in 2021 versus 82%, n=99

in 2013). These findings seemed to be more positive compared with other studies

which reported that precarious employment was on the rise in libraries

(Henninger et al., 2019; O’Reilly, 2015; The Canadian Press, 2016) and that

minorities were disproportionately affected (CUPE, 2017). Henninger et al.

(2020) analyzed job postings and found that employees with managerial

positions, advanced degrees, or more experience, and positions requiring an

MLIS were least likely to be precarious. In the 2021 survey, a vast majority of

the librarians had an MLIS or equivalent, one of five librarians had

professional degrees, and two of five librarians had at least two graduate

degrees. Also, 65% had more than five years of experience as a librarian. These

factors might have helped them secure stable jobs. Given the small sample size

of this survey, it might also be possible that those working on part-time or

temporary jobs were not participating in the 2021 survey; hence their

proportions might be underestimated.

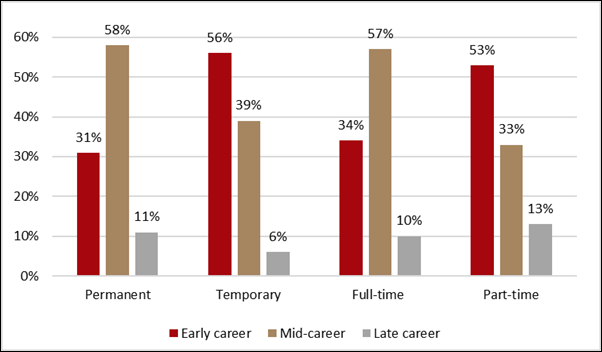

This research further examined employment of VMLs by career stage. Career

stage consists of early career, mid-career, and late career. However, the

concept of each career stage is open to interpretation. It is either based on

year of graduation from an MLIS program (Delong et al., 2015b), or post-MLIS

experience in a librarian role and the number of years the librarian has worked

for their current employer (Tucker, 2008). The data collected in the 2021

survey did not align with these studies. For instance, the survey asked about

years of librarian experience, but did not ask how many years the librarians

worked for their current employer. Therefore, it was not possible to analyze

the career stage as defined in the above studies. Instead, the authors referred

to Sullivan (2011) and Morison et al. (2006), who defined career stage by age.

This research broke down the sample into three subgroups: early career (ages

26-35, 34%, n=56), mid-career (ages 36-55, 56%, n=89) and late career (ages

55+, 10%, n=16). As illustrated in Figure 9, of all librarians in permanent or

full-time positions, around one third were at early career stage and over half

were at mid-career stage. On the contrary, early career librarians comprised

over a half of those in temporary or part-time positions. Early career minority

librarians seemed to have more challenges securing a full-time or permanent job

than their mid-career peers, as manifested through the experiences of some new

librarians (Ford, 2021; Lee, 2020). However, the results from a chi-square

analysis of this research indicated that there was no statistically significant

relationship between career stage and full-time or part-time employment, X2 (4, N = 159) = 3.86, p = .426, or between career stage and permanency of the employment,

X2 (4, N = 161) = 5.22, p = .266.

Figure 9

Employment by career stage.

Leadership Positions

In terms of their current position, 69% (n=110) of the 160 respondents were

not in managerial positions. An equal share (13%, n=21 each) were supervisors

and middle managers (e.g., branch head, department head). Only 5% (n=8) were

senior administrators (e.g., head/chief librarian, director, or

deputy/assistant head, chief, director). In comparison, CARL’s 2021 survey

revealed 14.4% of senior leaders identified as racialized, compared to 20% of

all library staff (CCDI, 2022). Furthermore, 8Rs 2014 Practitioner Survey

reported that 55% of CARL librarians were not in management positions and 15%

were senior administrators (Delong et al., 2015b, p.18). Participants expressed

their frustration by lack of “racial diversity among librarians” and being

“flat out dismissed” for expressing such concerns. In addition, they were

accused of being frustrated that they could not find jobs. In one situation

where the respondent wrote:

I was the most qualified and experienced person applying

to run my library and acted successfully in the job for over 8 months, I failed

the standardized leadership tests and was screened out of the competition and a

non-MLIS candidate with no library experience was placed in the leadership

positions.

The findings from this research supported that VMLs were less likely to be

working in senior administration positions for various reasons including lack

of leadership training. Respondents mentioned attending mentorship programs

such as the ARL Leadership and Career Development Program (ARL. n.d.-a), Certificate program on Public Library

Leadership (Ontario Library Service, n.d.), and Public Library InterLINK (n.d.)’s LLEAD program, all of which have a

focus on developing leadership skills. It should be noted that there are no

leadership programs that aim to develop minority library leaders in Canada.

Some libraries have tailored leadership programs for their employees; however, none

focuses on visible minority employees and their leadership skills development.

Salary

Respondents were asked about their gross yearly salary. About 17% (n=26) of

the 158 respondents reported a salary at $60,000 or less, 55% (n=86) reported a

salary between $60,001 and $100,000, 25% (n=40) reported a salary above

$100,000, and 4% (n=6) preferred not to answer. According to the 2016 Canadian

Census data (Statistics Canada, 2018a), the median employment income for VMLs

was $59,710, meaning half of the total 1,055 VMLs had an employment income

above this amount, and half had an employment income below this amount. Hence,

using $60,000 as an approximate benchmark, 80% of VMLs in the 2021survey earned

more than this amount compared to 50% of the general visible minority librarian

population in the 2016 Census.

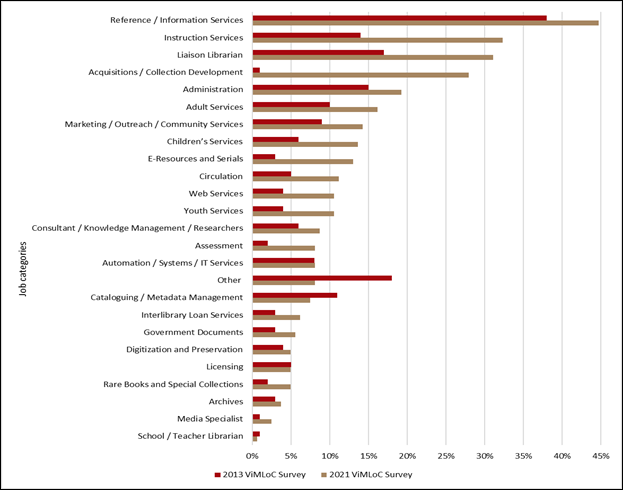

Job Categories

Respondents were asked to select as many of the job categories that match

their current job responsibilities. As shown in Figure 10, the majority worked

in Reference/Information Services (45%, n=72), followed by Instruction Services

(32%, n=52), and as Liaison Librarians (31%, n=50). Their proportions were 38%

(n=46), 14% (n=17), and 17% (n=20), respectively, in 2013. Those working in

Acquisitions/Collection Development accounted for 28% (n=45) in 2021 compared

to only 1% (n=1) in 2013. The rate of librarians working in

Cataloguing/Metadata Management was 7% (n=12) in 2021 versus 11% (n=13) in

2013. There were no changes in the proportions of respondents working in

Automation/Systems/IT Services, Licensing, and School/Teacher Librarian jobs.

Moreover, additional job categories were added in the 2021 survey to reflect

recent trends in librarian responsibilities, including Public Services (29%,

n=47), Research Services (27%, n=43), User Experience (14%, n=23), Project

Management (12%, n=19), Data Management and Curation (8%, n=13), Bibliometrics

(7%, n=11), Copyright (7%, n=12), and Scholarly Communications (6%, n=10).

Mentorship Experience

In the 2021 survey, of the 160 respondents, 58% (n=93)

indicated that they sought support from mentors throughout their library

career. 54% (n=50) of those respondents participated in formal mentorship

programs and nearly half (48%, n=45) had a visible minority mentor. These

figures were much higher than those reported in Kandiuk’s

(2014) study, which found that 32% (n=18) of VMLs had been mentored, with only

22% (n=4) of them engaged in a formal mentoring relationship, and the same

number had a visible minority mentor.

Forty-three respondents participated in formal mentorship

programs that were offered in workplaces (n=6), library schools (n=7), or

professional associations (n=30). Thirteen librarians mentioned participating

in more than one formal mentorship program. The most cited professional

association offering a mentorship program was ViMLoC

(n=15), followed by Ontario Library Association (n=8), British Columbia Library

Association (n=6), among others.

Figure 10

Job categories.

When asked how mentors were helpful in supporting them,

26% (n=24) of the respondents indicated “extremely helpful”, 32% (n=30)

indicated “very helpful”, 30% (n=28) indicated “moderately helpful”, 9% (n=8)

indicated “slightly helpful”, and 3% (n=3) indicated “not at all helpful”. We

further separately examined the librarians who engaged in formal and informal

mentorship (Table 3). Respondents engaging in formal and informal mentorship

were nearly equivalent in their rates of feeling the mentors were extremely

helpful, very helpful, and moderately helpful. There was a divergence of more

negative mentorship experiences from formal mentorship programs. 6% of the

librarians in formal mentorship did not find their mentor helpful at all,

whereas no respondents in informal mentorship thought so. These findings

reflected those of Damasco and Hodges (2012), where

academic librarians of colour were more likely to

cite informal mentoring as an effective form of professional development than

formal mentoring and perceive formal mentoring as an ineffective form compared

to informal mentorship (p. 293). We performed a chi-square test to further

examine the relationship between the type of mentorship and participants’

perception of the helpfulness of mentorship. The relation was not statistically

significant, X2 (4, N = 93) = 3.44, P = .488 (Table 3).

We thought it would also be useful to examine whether

these librarians perceived the value of mentorship differently if their mentor

was a visible minority. In Table 3, the librarians who had a visible minority

mentor were more likely to feel that their mentors were extremely helpful (33%

versus 19%) or very helpful (38% versus 27%) as compared to those who had a

non-visible minority mentor. Conversely, the librarians who did not have a

visible minority mentor were more likely to find their mentors were moderately

helpful (40% versus 20%), slightly helpful (10% versus 7%), and not helpful at

all (4% versus 2%). However, the chi-square test indicated that there was no

significant relationship between visible minority status of the mentor and

mentees’ perception of the helpfulness of mentorship, X2 (4, N = 93)

= 6.35, P = .175 (Table 3).

Table 3

Perceptions of the Helpfulness of Mentorship

|

Type of

Mentorship |

Extremely helpful |

Very helpful |

Moderately helpful |

Slightly helpful |

Not helpful |

Chi-square Value |

P value |

|

Formal mentorship |

13 (26%) |

16 (32%) |

15 (30%) |

3 (6%) |

3 (6%) |

3.44 |

0.488 |

|

Informal

mentorship |

11 (26%) |

14 (33%) |

13 (30%) |

5 (12%) |

0 (0%) |

||

|

Minority mentor |

15 (33%) |

17 (38%) |

9 (20%) |

3 (7%) |

1 (2%) |

6.35 |

0.175 |

|

Nonminority mentor |

9 (19%) |

13 (27%) |

19 (40%) |

5 (10%) |

2 (4%) |

There could be a couple of reasons why there was no difference in their

perceptions between having or not having a minority mentor, for example, lack

of visible minorities in managerial or senior administrative roles, or lack of

public knowledge of their racial identity. However, two of the respondents

highlighted the importance of having a minority mentor:

Mentors are so important for

BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour]

librarians. Most of the things I know about librarianship, about the unsaid

things I should know (knowledge sharing) or how to navigate this field, come

from wonderful and talented BIPOC librarians, who deserve their flowers and

increased pay! Honestly, I think mentors are the primary reason most of us

early career BIPOC librarians stay in this field. So, please continue the

program or create a space to informally or formally interact

more. BIPOC/visible minority librarians are often alone at their jobs

and having support from others is uplifting and empowering.

In formal mentorship programs,

I have not had a mentor from a visible minority group. However, I've had

informal mentors who are people of colour who have

been generous with sharing their experience and perspectives about issues like

feeling tokenized, moving to a new city that is less diverse, the dynamics of

EDI committees, and the lack of movement on issues around social justice

(racial and otherwise) in libraries.

Findings and Recommendations

In light of the

research findings, the authors would like to make the following recommendations

from the perspectives of the Canadian library profession, library

administrators, VMLs, and ViMLoC network.

Canadian Library Profession

There is fluctuation in which groups of racialized

minority librarians increased or decreased with the two surveys. The change in

numbers may be connected to the immigration patterns in Canada. However, the

truth remains that the VMLs continue to grow in numbers and are looking for

opportunities. Although many are still in career exploration stages, 38% of

librarians have 6-15 years of work experience. However, 67% of first generation

or immigrant librarians and 73% of second generation librarians are not in

leadership positions. Divided by ethnicity, 64% of Black librarians, 79% of

Chinese librarians, and 58% of South Asian librarians are not in such

leadership roles.

Recommendation: Regarding VMLs, there is a huge market

that the Canadian library profession has left untapped for future leadership

positions, thus depriving the profession of diverse talents and perspectives.

The library profession would benefit from a program that helps VMLs visualize

themselves in leadership positions and succeed in their leadership undertaking.

As Hines (2019) mentioned, leadership programs continue

to reinforce biased structures. Most Canadian librarians attend leadership

programs from the United States such as the Leadership and Career Development

Program or the Mosaic program (ARL, n.d.-a., n.d.-b). While these programs are

immensely helpful, they have an American focus; costs are in American dollars

and there is a requirement to travel to the United States. Due to costs and

travel needs outside of Canada, this could be an impediment to VMLs in their

leadership development.

Recommendation: The Canadian library profession needs a

library leadership program that focuses on racialized minorities, offered in

both English and French and through a hybrid model that includes both online

and in-person formats.

There are non-ALA accredited librarians who are already

in Canada waiting to gain employment. However, there are no pathways for them

to assess their education and experience and compete equally in the job market.

Canadian librarianship could design pathways to evaluate international

librarian credentials through programs such as the International Qualifications

Assessment Service (Government of Alberta, 2022), or other similar assessment

bodies within their campuses. For example, the British Columbia Institute of

Technology (n.d.) has an International Credential Evaluation Service dedicated

to their employees and students. Canadian librarianship can work with the

Canadian Information Centre for International Credentials (n.d.) or the

Alliance of Credential Evaluation Services of Canada (n.d.) to create a

standardized evaluation process for library courses and programs. Certificate

programs to upgrade skills could be an option, however, this would still be a

cost impediment for many first-generation immigrant librarians who already have

a degree, experience, and are new to the country. Universities that offer

professional library degrees could consider offering certification programs to

these librarians so they do not have to pay the full fees to receive a degree.

The Canadian library profession, library associations, and academic library

standards on hiring should mandate that such programs, along with previous

experience in the profession be accepted for hiring these librarians as equals

to ALA-accredited librarians. Their additional master’s and doctorate degrees

also need to be taken into consideration.

Recommendation: Canadian librarianship could design

pathways to assess, and if necessary, upgrade international librarian

qualifications.

Library Administrators

As the results of this research show, there is a conspicuous lack of

racialized librarians in management or leadership positions. As one respondent

pointed out, participants were tested for leadership skills through a test. The

respondent considered this “a barrier to racialized employees…seeking higher

leadership opportunities,” but their feedback of the issue of equity in such

tests were not addressed by their administration. More than one respondent

mentioned feeling isolated or experiencing racial microaggressions in their

current positions and were disappointed that their concerns were not being

heard by their leadership. Library administrators could encourage and coach

these minority librarians about their career goals to include them in the

succession plan and groom them for future leadership opportunities. This would

also be one way for library administrators to sustain their EDI commitments and

strengthen their retention practices.

Recommendation: All library leaders need to undergo ongoing training

through their institutions, library and national

associations, so they understand the perspectives of minority librarians.

Leaders should also consider mentoring and preparing BIPOC in their

institutions for future leadership positions.

The survey result shows that four of the nine participants with

international non-ALA accredited degrees are currently employed. This may

suggest that there exists a possibility for Canadian libraries to recognize

non-ALA accredited degrees. In fact, many American academic library job

postings are broadening the eligibility criteria by changing the education

requirements from ALA accredited degrees to be more inclusive of foreign LIS

education (Burtis et al., 2010). In CARL’s guidelines

on hiring and retaining diverse talent, one of the recommended strategies is to

“consider broadening the eligibility for librarian positions to be inclusive of

LIS accredited degrees beyond ALA-accreditation” (CARL, 2020). Another

important question to be considered is whether the work experience of these

four librarians would benefit their future career paths in librarianship. Would

their experience give them an equal standing along with librarians who have an

ALA-accredited degree, or are they destined to stay in their current positions

and status for fear of losing what they currently have?

Recommendation: Library administrators who are not hiring librarians with

non-ALA accredited degrees could examine the reasons why and the processes of how

some libraries are able to do so.

Visible Minority Librarians

An increased number of first

generation librarians responded to the 2021 survey than the previous one. For

visible minorities who want to enter Canadian librarianship, it is important to

consider additional training or knowledge to avoid culture shock while working

in Canadian libraries. It is essential to know how to work with patrons, their

rights, the design and delivery of library policies, and their impact on

practice and patrons. It is important to understand the structure of libraries.

For example, what does it mean when a library is considered regional versus

public, or college versus university, especially in terms of its structure,

governance, and funding? It is also important for these librarians to find a

network to get support in their job search, in creating their resumes or

building CVs, and practice interview skills with trusted colleagues.

Additionally, librarians can take advantage of many learning opportunities

outside of library schools. For example, the Library Juice Academy (2022)

offers regular courses on many current and relevant library topics. Librarians

can also join many library association listservs to receive updated information

on library happenings. If small costs are not an issue, librarians can join

library associations for a small membership fee. Such membership may provide

access to knowledge resources, webinars, and other informational materials,

which may be valuable when preparing for interviews.

Recommendation: VMLs need to be proactive in finding learning, network, and

job opportunities in Canada.

ViMLoC

The 2013 survey identified the importance of mentoring

support for visible minority librarians. Thereafter, ViMLoC

developed its own mentorship program and ran the first session during

2013-2014. This program was reinitiated in 2018 and continued to run on an

annual basis. The findings from the 2021 survey showed that 35% (n=15) of the

librarians participated in the ViMLoC mentorship

program and two out of three librarians found the mentors were extremely

helpful or very helpful. ViMLoC can support VMLs through

other efforts, for example, organizing panel presentations that host minority

library leaders and highlight their pathways into leadership. Such

presentations will empower VMLs and help them design their own career pathways.

ViMLoC can collaborate with other associations as

well. While ViMLoC currently does not have the

resources to host conferences similar to the Joint

Conference of Librarians of Color (2022), it could connect with Canadian Health

Libraries Association (CHLA), CAPAL, Congrès des profesionnel·le·s de l’information

(CPI) or Ontario Library Association (OLA) conferences and add a minority

focused session/stream in those conferences. The Canadian Journal of Academic

Librarianship (2019) hosted a special issue with a focus on diversity. In addition,

ViMLoC has partnered with University of Toronto

Libraries to organize the Navigating the Field workshop series targeted for

those new to applying for academic jobs (ViMLoC,

2021).

Recommendation: ViMLoC should

continue to implement the mentorship program and pursue more collaborative

opportunities to support VMLs.

Limitations

First, 162 visible minority librarians completed the 2021 survey,

representing approximately 15% of the visible minority librarian population

(1,055) based on the 2016 Census data (Statistics Canada, 2018a). This means

that the findings from this research may not provide a complete picture of the

visible minority librarian population in Canada.

Second, data collection errors might occur in the survey and affect analysis

results in this research. Representation data for members of visible minorities

was based on voluntary self-identification. The information on librarians was

self-reported such as disability status, salary, years of librarian experience,

and respondent’s perception of how mentorship was helpful. Regarding gender identity, the 2021 survey

used the binary biological terms, male/female, which are normally used for

gender and not interchangeable with gender identity. In addition, transgender

identity was recorded separately from male/female identity, which might have

resulted in reporting errors.

Third, there is a limitation of using age to assume a career stage. Some

people pursue librarianship as a second or third career. Hence, they may be

older in age, but are still in an early career stage. Someone may enter the

librarian profession at a very early age, and possibly reach a mid-career stage

before the age of 36.

Finally, the 2021 survey comprised 36 questions, three times the number of

questions covered in the 2013 survey. Wording for seven out of 12 original

questions were

updated when it was determined that they would result in an improvement to the

data. However, this limited the authors’ ability to compare results between the

two surveys.

Conclusion

With more visible minority librarians participating in the 2021 survey,

this larger snapshot provided a more robust and updated perspective of

potential changes in the population compared to the 2013 survey. Differences

were identified with regard to ethnic identity,

generation classification, where their MLIS or equivalent degree was received,

type of library, geographic location, and job responsibilities. The 2021 survey

also explored other aspects of these librarians not covered in the previous

survey, such as age, disability status, non-MLIS education, librarian

experience, salary, management positions, and mentorship experience. Based on

the survey findings, the profession needs to create pathways for VMLs to

explore leadership positions. Mentorship and leadership opportunities offer

such librarians a sense of belonging and sense of possibility for their own

future. Canadian librarianship could design pathways for non-ALA accredited

librarians with expertise and experience from their home country to secure

employment in Canada. Professional associations and library administrators also

need to make continued efforts to support these librarians to create an

inclusive space in their libraries.

Author

Contributions

Yanli Li:

Conceptualization, Data curation, Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project

administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing –

review & editing Maha Kumaran: Conceptualization, Investigation, Qualitative

Analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Allan Cho: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing –

original draft, Writing – review & editing Valentina Ly:

Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original

draft, Writing – review & editing Suzanne Fernando:

Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft,

Writing – review & editing Michael David Miller: Conceptualization,

Investigation, Methodology, Translation, Writing – original draft, Writing –

review & editing

References

Alliance of Credential

Evaluation Services of Canada. (n.d.). About

the ACESC. https://canalliance.org/en/

Association of Research

Libraries (ARL). (n.d.-a). Leadership and

career development program. https://www.arl.org/category/our-priorities/diversity-equity-inclusion/leadership-and-career-development-program/

Association of Research Libraries (ARL). (n.d.-b). Mosaic program. https://www.arl.org/category/our-priorities/diversity-equity-inclusion/arl-saa-mosaic-program/

British Columbia Institute of Technology. (n.d.). International credential evaluation service.

https://www.bcit.ca/ices/

Burtis, A.T., Hubbard,

M.A., & Lotts, M.C. (2010). Foreign LIS degrees

in contemporary U.S. academic libraries. New

Library World, 111(9/10), 399-412. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074801011089323

Canadian Association of Professional Academic

Librarians (CAPAL). (2016). 2016 census

of Canadian academic librarians user guide and results summary. https://capalibrarians.org/wp/wp-content/

uploads/2016/12/Census_summary_and_user_guide_December_16_2016.pdf

Canadian Association of Professional Academic

Librarians (CAPAL). (2019). 2018 census

of Canadian academic librarians user guide and results summary. https://capalibrarians.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/2018_Census_March_24_2019.pdf

Canadian Association of Research Libraries (CARL).

(n.d.). Diversity and inclusion survey. https://www.carl-abrc.ca/diversity-and-inclusion-survey/

Canadian Association of Research Libraries (CARL).

(2020). Strategies and practices for

hiring and retaining diverse talent. https://www.carl-abrc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CARL-Strategies-and-Practices-for-Hiring-and-Retaining-Diverse-Talent-1.pdf

Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT).

(2019). Almanac of post-secondary

education 2019 - academic staff: Table 3.8. https://www.caut.ca/resources/almanac/3-academic-staff

Canadian Journal of Academic Librarianship. (2019).

Special focus on diversity. https://cjal.ca/index.php/capal/catalog/category/diversity

Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE). (2017,

October 24). Employment increasingly precarious

in public libraries, survey finds. https://cupe.ca/employment-increasingly-precarious-public-libraries-survey-finds

CCDI Consulting. (2022, May). Diversity census

and inclusion survey: Insights report. https://www.carl-abrc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/CARL-Diversity-Meter-Insights-Report-Final.pdf

Damasco, I. T., &

Hodges, D. (2012). Tenure and promotion experiences of academic librarians of

color. College & Research Libraries,

73(3), 279-301. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl-244

Delong, K., Sorenson, M., & Williamson, V.

(2015a). 8Rs practitioner survey data.

https://doi.org/10.7939/DVN/10459

Delong, K., Sorensen, M., & Williamson, V.

(2015b). 8Rs Redux CARL libraries human

resources study. http://www.carl-abrc.ca/wp-content/uploads/docs/8Rs_REDUX_Final_Report_Oct2015.pdf

Ferguson, J. (2016). Additional degree required?

Advanced subject knowledge and academic librarianship. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 16(4), 721-736. http://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2016.0049

Ford, A. (2021). The library employment landscape:

Job seekers navigate uncertain terrain. American

Libraries, 52(5), 34-37. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2021/05/03/library-employment-landscape/

Government of Alberta. (2022). International Qualifications Assessment

Service. https://www.alberta.ca/international-qualifications-assessment.aspx

Government of Canada. (2021). Employment equity act. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/E-5.401/page-1.html#h-215195

Guise, J. (2015). Succession planning in Canadian academic libraries. Chandos Publishing.

Harrington, M. R., & Marshall, E. (2014).

Analyses of mentoring expectations, activities, and support in Canadian

academic libraries. College &

Research Libraries, 75(6), 763. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.75.6.763

Henninger, E., Brons, A.,

Riley, C., & Yin, C. (2019). Perceptions and experiences of precarious

employment in Canadian libraries: An exploratory study. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice

and Research, 14(2), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v14i2.5169

Henninger, E., Brons, A.,

Riley, C., & Yin, C. (2020). Factors associated with the prevalence of

precarious positions in Canadian libraries: Statistical analysis of a national

job board. Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice, 15(3),

78-102. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29783

Hines, S. (2019). Leadership development for

academic librarians: Maintaining the status quo? Canadian Journal of Academic Librarianship, 4, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.33137/cjal-rcbu.v4.29311

Jennings, A., & Kinzer, K. (2022). Whiteness

from top down: Systemic change as antiracist action in LIS. Reference Services Review, 50(1), 64-80. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-07-2021-0027

Joint Conference of Librarians of Color. (2022). JCLC 2022. https://www.jclcinc.org/

Kandiuk, M. (2014).

Promoting racial and ethnic diversity among Canadian academic librarians. College & Research Libraries, 75(4), 492–556. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.75.4.492

Kumaran, M. (2012). Leadership in libraries: A focus on ethnic-minority librarians. Chandos Publishing.

Kumaran, M. (2015). Succession planning process

that includes visible minority librarians. Library

Management, 36(6/7), 434-447. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-12-2014-0138

Kumaran, M., & Cai, H. (2015). Identifying the

visible minority librarians in Canada: A national survey. Evidence based library and information practice, 10(2), 108-126. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8ZC88

Kung, J. Y., Fraser, K. L., & Winn, D. (2020).

Diversity initiatives to recruit and retain academic librarians: A systematic

review. College & Research Libraries,

81(1), 96-108. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.81.1.96

Law, M. (2001). Mentoring programs: In search of

the perfect model. Feliciter, 47(3),

146-148.

Lee, Y. (2020). Bumpy inroads: Graduates navigate a

precarious job landscape. American Libraries, 51(5),

51. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2020/05/01/bumpy-inroads-library-job-precarity/

Li, Y. (2021). Racial pay gap: An analysis of CARL

libraries. College & Research

Libraries, 82(3), 436-454. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.82.3.436

Library Juice Academy. (2022). All courses. https://libraryjuiceacademy.com/all-courses/

Mackinnon, C., & Shepley, S. (2014). Stories of

informal mentorship: Recognizing the voices of mentees in academic libraries. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library

and Information Practice and Research, 9(1),

1-9. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v9i1.3000

Morison, R., Erickson, T., & Dychtwald, K.

(2006, March). Managing middlescence. Harvard

Business Review, 84(3), 78-86. https://hbr.org/2006/03/managing-middlescence

Ontario Library Service. (n.d.). Advancing public library leadership

institute. https://www.olservice.ca/consulting-training/apll

O’Reilly, M. (2015, January 29). The impact of precarious work in Canada’s

libraries. Presentation to the Ontario Library Association, Toronto, ON.

Oud, J. (2008). Adjusting to the workplace:

Transitions faced by new academic librarians.

College & Research Libraries, 69(3), 252-266. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.69.3.252

Popowich, E. (2011). A

forecast for librarians facing retirement. Feliciter,

57(6), 220-221.

Public

Library InterLINK. (n.d.). Project LLEAD. https://www.interlinklibraries.ca/services/project-llead/

Statistics Canada. (2017, November 29). Labour Force Status (8), Visible Minority (15),

Immigrant Status and Period of Immigration (11), Highest Certificate, Diploma

or Degree (7), Age (13A) and Sex (3) for the Population Aged 15 Years and Over

in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Metropolitan

Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2016 Census - 25% Sample Data. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/dt-td/Rp-eng.cfm?TABID=2&LANG=E&A=R&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=01&GL=1&GID=1341679&GK=1&GRP=1&O=D&PID=110692&PRID=10&PTYPE=109445&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2017&THEME=124&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=&D1=0&D2=0&D3=0&D4=0&D5=0&D6=0

Statistics Canada. (2018a, March 28). Occupation—National Occupational

Classification (NOC) 2016 (691), Employment Income Statistics (3), Highest

Certificate, Diploma or Degree (7), Visible Minority (15), Work Activity During

the Reference Year (4), Age (4D) and Sex (3) for the Population Aged 15 Years

and Over Who Worked in 2015 and Reported Employment Income in 2015, in Private

Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories and Census Metropolitan Areas,

2016 Census—25% Sample Data. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/global/URLRedirect.cfm?lang=E&ips=98-400-X2016356

Statistics Canada. (2018b, May 31). Census indicator profile, based on the 2016

Census long-form questionnaire, Canada, provinces and territories, and health

regions (2017 boundaries). https://doi.org/10.25318/1710012301-eng

Statistics Canada. (2021, September 30). Classification of generation status. https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3VD.pl?Function=getVD&TVD=117200&CVD=117200&CLV=0&MLV=1&D=1

Sullivan, D. (2011). Work envy, workhorses

and the mid-career librarian. In D. Lowe-Wincentsen

& L. Crook (Eds.), Mid-career library

and information professionals: A leadership primer (pp. 113-135). Chandos Publishing.

Taleban, S. (2016). The

journey of a non-ALA-accredited librarian in Canada. British Columbia Library Association. https://bclaconnect.ca/perspectives/2016/05/01/an-iranian-librarian-in-canada-on-attaining-an-ala-accredited-mlis/

The Canadian Information Centre for International

Credentials. (n.d.). Assessor portal. https://www.cicic.ca/853/assessor.canada.canada

The Canadian Press. (2016, March 27). Librarians

fight rise of precarious work. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/precarious-work-librarians-1.3508778

Tucker, J. C. (2008). Development of midcareer

librarians. Journal of Business &

Finance Librarianship, 13(3), 241-248. https://doi.org/10.1080/08963560802183146

University of Victoria. (2015). Employment Equity Plan 2015 – 2020. https://www.uvic.ca/equity/assets/docs/eep2015.pdf

Visible Minority Librarians of Canada (ViMLoC). (n.d.). ViMLoC operating

values. https://vimloc.wordpress.com/

Visible Minority Librarians of Canada (ViMLoC). (2021). A

UTL & ViMLoC workshop series: Navigating the

field: Finding that first academic librarian position in Canada. https://vimloc.wordpress.com/workshop-events-series/

Appendix

Survey Questionnaire

Section One: Demographic

Information

1.

The Canadian Employment Equity Act defines visible minorities as “persons,

other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in

colour.” The visible minority population consists mainly of the following

groups: Chinese, South Asian, Black, Arab, West Asian, Filipino, Southeast

Asian, Latin American, Japanese and Korean. Are you a

visible minority librarian currently working in Canada?

o Yes

o No

2.

What group do you belong to or which group fits you the best?

o Arab only (includes Egyptian, Kuwaiti

and Libyan)

o Black only

o Chinese only

o Filipino only

o Japanese only

o Korean only

o Latin American only

o South Asian only (includes Bangladeshi, Indian,

Pakistani, and Sri Lankan)

o Southeast Asian only

(includes Vietnamese, Cambodian, Malaysian, and Laotian)

o West Asian only

(includes Afghan, Assyrian, and Iranian)

o White and Arab

o White and Black

o White and Chinese

o White and Filipino

o White and Japanese

o White and Korean

o White and Latin American

o White and South Asian

o White and Southeast Asian

o White and West Asian

o White and multiple visible minorities

o Multiple visible minorities

o Other (please specify) _________________

3.

Tell us if you are a first generation minority

librarian or not. First generation would mean that you were born elsewhere but

moved to Canada at some point in your life. Second generation would mean you

were born in Canada to immigrant parents. If you would like to add an

explanation about this, please use the text box below, such as your age or the

year when you came to Canada.

o First

generation ___________________

o Second generation ________________

o Other ___________________________

4.

Do you consider yourself to have a disability?

o Yes (please elaborate if you wish)

___________________

o No

5.

What is your age?

o 20-25

o 26-30

o 31-35

o 36-40

o 41-45

o 46-50

o 51-55

o 56-60

o 61-65

o 65+

6.

What is your gender identity?

o Female

o Male

o Transgender

o Two Spirit

o Other (please elaborate if you wish)

________________

o Prefer not to answer

Section

Two: Education

7.

When did you receive your MLIS / MLS degree or equivalent?

o Before or during 1980

o Between 1981 and 1989

o Between 1990 and 1999

o Between 2000 and 2009

o Between 2010 and 2019

o After 2019

8.

Where did you receive your MLIS / MLS degree or equivalent? Answer Q9 if option

one is selected, otherwise skip to Q10-15.

o From an

ALA-accredited Canadian library school

o From an

ALA-accredited American library school

o From a

library school outside North America

o Other (Please specify) _______________

9. Please select the university that you

received your degree.

o University of British Columbia

o University of Alberta

o University of Western Ontario / Western University

o University of Toronto

o University of Ottawa

o Université

de Montréal

o Dalhousie

University

o McGill University

10.

Please specify the COUNTRY where you received your library degree:____________

11.

Please provide the name of your institution:_____________

12.

Does your current employer recognize your professional library degree in terms

of your position?

o Yes

o No

13.

Have you taken any courses of study or programs in Canada to supplement your

library degree?

o Yes

o No

14.

Please provide the name of the course or program:______________

15.

How, if at all, has this made a difference to how your employer and the library

community recognize your credentials?__________________

16.

In addition to your MLIS / MLS degree or equivalent, please indicate other education

you attained. Select all that apply.

o Professional degree (what degree? e.g. Law)__________________

o Second Master’s Degree (what discipline?)

________________

o Third Master’s Degree (what discipline?)________________

o PhD (what discipline?) ___________________

o Additional Degrees, Certificates, or Diplomas (what

type?) ________________

o None of the above

Section Three: Employment

17.

How many total years have you worked as a librarian?

o 0-5

o 6-10

o 11-15

o 16-20

o 21-25

o 25+

18.

What inspired you to enter the library profession? Select all that apply.

▢ I was inspired

by a family member or friend that worked in the profession

▢ I got an entry

level job in a library

▢ Library role

models influenced me

▢ I thought it

would be an interesting profession

▢ I thought it

would be a well paying job

▢ I thought it

would be a rewarding job because I would have the opportunity to help others

▢ I liked the work

environment in a library

▢ I had the

expertise and skills fit for the library job

▢ I enjoyed books

and reading

▢ Other (please

elaborate) ___________________

19. Which province / territory do you

currently work in?

o Alberta

o British

Columbia

o Manitoba

o New Brunswick

o Newfoundland and Labrador

o Northwest

Territories

o Nova Scotia

o Nunavut

o Ontario

o Prince

Edward Island

o Quebec

o Saskatchewan

o Yukon

o Other (if you are working for a Canadian Library

outside of Canada) _________

20.

What type of library are you currently working at?

o Public Library

o Regional Library

o Academic Library

o College Library

o Special Library (what type? e.g., Government,

Religious Organization) _______

o School Library

o Other (please specify) __________

21.

Please select the job category(ies) that matches your

current job responsibilities. Select all that apply.

o Acquisitions /

Collection Development

o Administration

o Adult Services

o Archives

o Assessment

o Automation /

Systems / IT Services

o Bibliometrics

o Cataloguing / Metadata Management

o Children’s

Services

o Circulation

o Consultant /

Knowledge Management / Researchers

o Copyright

o Data Management and Curation

o Digitization and Preservation

o E-Resources and

Serials

o Government

Documents

o Instruction

Services

o Interlibrary Loan

Services

o Liaison Librarian

o Licensing

o Marketing / Outreach / Community Services

o Media

Specialist

o Project

Management

o Public

Services

o Rare

Books and Special Collections

o Reference /

Information Services

o Research

Services

o School /

Teacher Librarian

o Scholarly

Communications

o User

Experience

o Web

Services