Commentary

Announcing and Advocating: The Missing Step in the EBLIP Model

Clare Thorpe

Director, Library Services

Southern Cross University

Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia

Email: Clare.Thorpe@scu.edu.au

Received: 15 Sept.

2021 Accepted: 29 Sept.

2021

![]() 2021 Thorpe. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use,

distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is

properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes, and, if transformed, the

resulting work is redistributed under the same or similar license to this one.

2021 Thorpe. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use,

distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is

properly attributed, not used for commercial purposes, and, if transformed, the

resulting work is redistributed under the same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip30044

Introduction

The Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice (EBLIP) model “has been described as a

structured approach to decision making” (Hallam, 2018, p. 456) and a method for

problem solving (Howard & Davis, 2011). It consists of five sequential

stages that step a Library and Information Science (LIS) professional or team

through the EBLIP process. The five stages are Articulate, Assemble, Assess, Agree and Adapt, colloquially known as “The 5As” (Koufogiannakis,

2013). The model has iteratively evolved over the past 17 years. Yet it fails

to include one of the most important characteristics of evidence

based practice. This article argues that the model needs to evolve again

to explicitly highlight the importance and relevance of communicating EBLIP

outcomes and process to the local community and the professional evidence base.

A sixth “A” of Announcing or Advocating is proposed.

Evolution of the EBLIP

Model

The first

version of the model by Booth (2004) proposed five steps and established the

foundational principles of EBLIP. It emphasized a reliance on research

literature as the only source of evidence and focused on an individual

practitioner’s approach to a research task.

The steps

included:

- Defining the problem (Ask)

- Finding the best evidence in

the research literature (Acquire)

- Appraising the evidence (Appraise)

- Applying the evidence to

practice (Apply)

- Evaluating the change,

performance, or impact (Assess)

Booth (2009)

subsequently reflected on the five stages and proposed an amended version

whereby an evidence based practitioner would:

- Articulate the

problem

- Assemble the

evidence base

- Assess the

evidence

- Agree the

actions

- Adapt the

implementation

In the

evolved model Booth suggested that a feedback loop existed between the Agree-Adapt

steps and identified that decisions in libraries are often made by teams,

rather than individual practitioners. The revised model began to acknowledge

research literature and locally collected data as equally valid sources of

evidence.

Koufogiannakis (2013) validated Booth’s model in

her doctoral thesis, in which she argued for a broader definition of evidence

that included professional knowledge and local evidence alongside published

research. The final iteration of the five-step model was published in Koufogiannakis and Brettle’s 2016

book, Being Evidence Based in Library and

Information Practice, in which they stated that the five steps were

cyclical in nature and could be applied to both individual and group decisions

(p. 14).

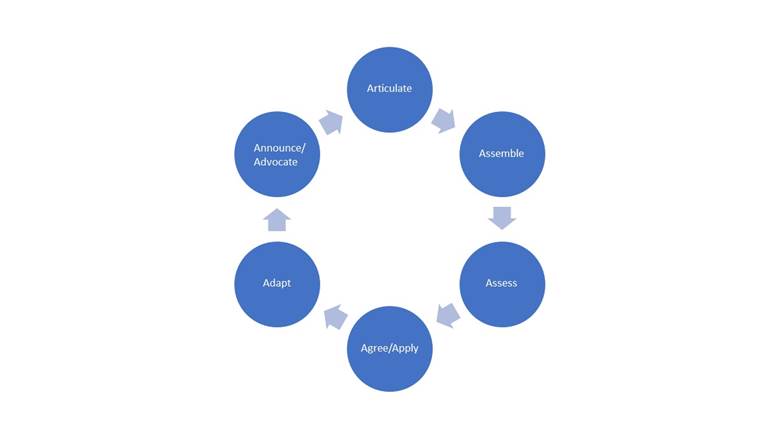

Figure 1

The EBLIP model (Koufogiannakis & Brettle, 2016, p. 14).

This version

of the model drew on a range of different evidence sources and was described as

a holistic and realistic depiction of the EBLIP process. The model has been

widely adopted and applied by individuals and teams, with Hallam (2018) noting

that the Koufogiannakis and Brettle

version allows practitioners to take ownership of the process, and fosters

critical reflective practice among LIS professionals.

Alternative Frameworks

Alongside the

evolution of the EBLIP model, a small number of related frameworks were

proposed and documented in the literature. Howard and Davis (2011) melded

design thinking with Booth’s original 2004 version of the model. Their approach

combined the philosophies of the two frameworks to produce a hybrid model of evidence based practice (EBP) and design thinking. The model

proposed six stages:

- Define the problem

- Undertake and appraise

research

- Prototype and test

- Implement the solution

- Evaluate the outcomes

- Engage in storytelling

Howard and

Davis’s (2011) hybrid EBP and design thinking model was the first to include a

step that explicitly identified the role of communication as a characteristic

of EBLIP. The sixth step—engage in storytelling—is described as “a process to close the loop and contribute to

the evidence base” (p. 19). Howard and Davis argued that when solutions to

complex workplace problems have been implemented and evaluated, it is important

to tell the story through informal and formal channels. They suggested there

are benefits to the individual, organization, and the broader profession in

documenting the process, the inputs (or evidence), and the learnings of the

EBLIP process in order to add to the evidence base that can be drawn on by other

LIS practitioners in the future.

Howlett

(2018) proposed a four-phase framework to describe how EBLIP may be undertaken

by academic libraries as a strategic engagement activity. Howlett challenged

the unidirectional nature of the EBLIP model, arguing that various stages of

the model are multi-directional, iterative in nature, and interconnected in

practice when applied to complex organizations. The proposed “lens” reduced the

steps or phases of EBLIP to four:

- Interpret

the

organizational context and strategic priorities

- Apply the

library’s strategy

- Measure the

outcomes

- Communicate

the

impact of the library’s strategic contribution

This model

emphasized the application of evidence based practice

through which academic libraries “[tell] the story of how the library

contributes to student and institutional success” (Howlett, 2018, p. 76).

Howlett argued that the communication step empowers library leaders to generate

influence and advocate for what the library is and what it achieves within

their university.

In Thorpe and

Howlett’s (2020) Evidence Based Library

and Information Practice Capability Maturity Model, the way in which a

library reported or communicated evidence was identified as an indicator of

maturity. More mature organizations focused on communicating for influence and

making evidence easily understood by the target audience (p. 97). Interview

respondents demonstrated varying degrees of appreciating and applying the power

of communication to demonstrate value and impact to local stakeholders. Staff

from libraries that showed a high level of EBLIP maturity could also articulate

the benefits of contributing to the LIS evidence base.

The

alternative frameworks view evidence based practice

from different perspectives. However, all explicitly feature a stage in which

LIS practitioners communicate their findings, processes, and outcomes.

Communication is emphasized as a key step that informs future research,

documents methodologies and processes, articulates the role of the library and

its staff, demonstrates value and impact, and builds the profession’s evidence

base.

Implicit or Explicit

Neither

Booth’s original models nor Koufogiannakis and Brettle’s widely adopted version explicitly identified a

step in which the LIS practitioner communicates their evidence based practice

to their stakeholders, clients, or peers. While Koufogiannakis

and Brettle did not include mention of communicating

(or advocating or announcing) as a step in their model, they have written about

the importance of communication within EBLIP. As early as 2004, Crumley and Koufogiannakis (2004) argued that:

Dissemination of research results is vital to the

progress of the profession as well as helping to improve practice. It involves

not only making your research available, but also ensuring that it is

accessible to others and presented in a manner that is easy to understand. (p.

127)

They promoted

communication within the library, to its parent organization, and externally to

the profession via informal and formal methods of dissemination, such as

conference presentations, journal clubs, scholarly publication, reports to

management, and personal networking (Crumley & Koufogiannakis,

2004).

Koufogiannakis and Brettle

(2016, pp. 165–166) recommended that LIS professionals engaging in EBLIP

should:

- Share their “learn[ing] with others in order to improve the knowledge of

the profession.”

- “Use … new knowledge or

evidence to convince or influence others of the best way forward or to

prove the value of their services.”

They

suggested that the importance of communication was implied throughout the

contributed chapters of their book and acknowledged that it was an aspect of

EBLIP which, at the time of publication, had not been well considered in the

literature (Koufogiannakis & Brettle,

2016, p. 166).

One way to

consider how to explicitly embed communication as a stage in the EBLIP model is

to consider the relationship between EBLIP and research processes. Hallam

(2018) drew parallels between the EBLIP model and research processes, stating

that one of the goals of evidence based practice is to inspire librarians to

conduct research. Nguyen and Hider (2018) also linked EBLIP with the benefits

of undertaking research as a librarian. They surmised that research is a key

tool for EBLIP, particularly in the academic library sector, where

practice-oriented research can be “harnessed by [library] management to

implement improvements and innovation” (p. 16). Writing, publishing,

disseminating and sharing the completed work is the final step in the research

process (Hallam, 2018, p. 457). Communicating research findings is a critical

and often required stage of the research process, particularly when publishing

research findings is mandated by funding bodies. If EBLIP is accepted as a form

of practitioner research, then it follows that communicating findings and

results should be a logical and explicit requirement of being evidence based LIS practitioners.

The omission

of a communication step as an endorsed and prioritized part of EBLIP could be

why scholarship and practitioner research are not widely accepted as a part of

LIS professionals’ work. Lamond and Fields’s (2020) review of 20 years of EBLIP

in New Zealand reported that it was difficult to find examples of EBLIP

application and development in the literature. Lamond and Fields (2020) assumed

that the published outputs were not representative of the EBLIP work undertaken

across the country. They purported that EBLIP in New Zealand was primarily

undertaken as an information gathering activity to solve workplace problems,

with little or no consultation of published literature or theory, and

subsequently not reported in the published literature as research outcomes (p.

31). Less formal examples were found in presentations, blog posts, product

reviews for vendors and were observed anecdotally at meetings and in

conversations. The failure of LIS practitioners to announce, report, and

publish their work makes it challenging to determine how widespread EBLIP

adoption is by individuals, teams, and organizations. Todd (2015) highlighted

the perceived invisibility of school librarians’ impact on student learning due

to a lack of research and an evidence base to support advocacy efforts in

Australia. For LIS practitioners committed to being evidence based, it should

be concerning that the impact of libraries engaging in EBLIP continues quietly

and remains mostly invisible to libraries’ funding organizations, clients, and

the profession. Figure 2 shows how the sixth step could be added to the EBLIP

model.

Announce and Advocate—The

Missing As

Why should

announcing, advocating, and communicating be made an explicit part in the EBLIP

model? I propose four benefits that may apply to individuals, libraries, and

the profession:

- To advocate and influence

- To contribute to the

profession’s evidence base

- To demonstrate professional

expertise

- To build organizational

capacity and maturity

Figure 2

The proposed evolution of the EBLIP model.

To Advocate and Influence

Libraries are

commonly reliant on funding from the organization they serve, be it a

university, government, or for purpose or for profit corporations. Using

evidence to influence decisions and decision makers is a key reason that

librarians adopt evidence based approaches in their

work (Partridge et al., 2010, p. 285). Howlett’s (2018) organizational lens

model argued that one purpose of EBLIP is to effectively communicate the

library’s contribution and value to its parent organization or funding body.

Lamond and Fields (2020) stated that evidence based reports have an increased

chance of getting funding for projects. Being able to articulate clearly the

evidence supporting a project, initiative, or business case is more likely to

influence stakeholders. In reporting evidence for advocacy and influence, it

pays to strategically consider the target audience. Crumley and Koufogiannakis (2004) argued that EBLIP needs to be

user-friendly and understandable by those to whom library staff report, as well

as to colleagues. While the message and the method of communication should have

a clear purpose and be easy to follow, evidence should be communicated in ways

that might influence the decision made by those in power. The EBLIP model can

be strengthened by emphasizing this activity in order to empower LIS

practitioners using evidence based practices to

achieve success.

To Contribute to the Evidence Base

Issues with

the quality and quantity of the LIS evidence base have acted as a barrier to

adopting and implementing EBLIP from the beginning of the movement (Haddow,

1997; Koufogiannakis & Crumley, 2006). This

reason alone should be enough to explicitly add a communication focused step to

the EBLIP model. Howard and Davis (2011) included storytelling in their model,

stating that sharing what has been learned adds to the evidence base locally

within a library, at its parent institution, and in the broader LIS profession.

Koufogiannakis and Crumley (2006) argued that

every librarian has a part to play in building up an

evidence base that is directly relevant to our decision-making needs. … Librarians need to start filling the gaps

and mending the seams of our professional body of knowledge in order for our

profession to advance. (p. 338)

Increasing

the quality, quantity, and diversity of work contributed to the evidence base

should also foster inclusion and diversity of opinion, inviting more voices and

alternative perspectives into the profession. Like the Critical Librarianship

movement, EBLIP is contextualized to local, social, political, and economic

environments (Drabinski, 2019). A model that endorses

and promotes the communication of EBLIP empowers the development of critical

librarianship in which evidence can challenge and be challenged. When

librarians use evidence to advocate, they bring an awareness to organisational

behaviour that can be named and professionally discussed in order to expose

bias in decision making (Koufogiannakis, 2013, p.

197). The critical nature of questioning that starts with the Articulate stage should reach a logical

conclusion with Advocacy. In doing

so, evidence based practice is well aligned with the Critical Librarianship movement

to document, uncover, and challenge assumptions in library structures, systems,

and services. For EBLIP to fully support the development of a community of

practice that “changes the profession for the better” (Koufogiannakis

& Brettle, 2016, p. 166), the model must promote

the importance of contributing to the profession’s evidence base.

To Demonstrate Professional Expertise

At its heart,

EBLIP promotes and develops “the mind-set of a critically reflective

practitioner” (Hallam, 2018, p. 457). In order for EBLIP to be an embedded and

valued part of everyday professional practice, it must be visible.

Communicating research findings promotes the benefits of being evidence based.

It encourages and supports practitioners who wish to develop their skills and

expertise in this space (Hallam, 2018). Appleton (2021) argued that the LIS

professionals should exhibit pride in their work, and should actively and

deliberately promote their research based

achievements. One strategy suggested by Appleton (2021) is to engage in

scholarly writing and presenting as a way to build the reputation of both

individual contributors and the library service. Crumley and Koufogiannakis (2004) stated that disseminating evidence based practice contributes to how librarians understand

and define their role. By announcing outcomes and achievements to the

community, evidence based practitioners can document their expertise in

reaching milestones and developing innovations, time-stamping projects for

future reference. If LIS professionals want to be evidence based, then the

communication and sharing of their achievements and enthusiasm should be a

defining feature of their professional expertise and identity.

To Build Organizational Capacity and Maturity

Library

services are human centred and human mediated. A culture of evidence

based practice within an organization requires a shared approach and

participation from all staff. Booth’s revision of the original model was partly

influenced by his observations of EBLIP applied within teams. Booth (2009)

noted that “a significant contributor to the success of any service change is

the motivation, involvement and commitment of the team” (p. 343). Lamond and

Fields (2020) viewed EBLIP as a way of developing staff. They described how

EBLIP benefits the library producing evidence based

outcomes and also develops the potential and performance of staff through the

process. The way in which evidence was communicated to influence organizational

decision making and to demonstrate value and impact was a key indicator of

EBLIP maturity in Thorpe and Howlett’s (2020) model. Staff who communicated

EBLIP within their libraries and to external audiences contributed to growing

the maturity of the library as an evidence based organization. The ability to effectively

communicate to different audiences via different channels is a core

professional skill for all LIS workers. Nguyen and Hider (2018) identified many

benefits for libraries in fostering a culture of research communication. The

benefits included “more efficient ways of working, better informed staff, the

production of evidence that can be used for advocacy, and professional kudos

for the library and individuals” (Nguyen & Hider, 2018, p. 16). Hallam

(2018) argued that employers should “provide opportunities and resources for

their staff to engage in EBP, including the dissemination of research findings

to the wider profession” (p. 460). In the COVID pandemic environment where

libraries have benefited from sharing knowledge, evidence, and experiences with

each other, it makes sense for the EBLIP model to demonstrate a commitment to

communication in order to build organizational capacity, resilience, and

maturity.

Conclusion

Koufogiannakis and Brettle

(2016) stated that their EBLIP model was “more about approaching practice with

a particular mindset, rather than about checking off steps in a process” (p.

165). Regardless of the authors’ intent, it is easy to default to using the

model as a step-by-step guide, especially for professionals beginning to engage

with EBLIP as a way of working and being. This makes the absence of a step that

promotes the communication of EBLIP activities a challenge for the future of

the profession. If a generation of LIS professionals learn to engage in EBLIP

without announcing, advocating, and communicating their work, then criticisms

of the validity of the profession’s evidence base will endure. Communicating in

an evidence based way should be an explicit part of the EBLIP professional

identity. By adding Advocate and Announce

to the model as the “6th A,” LIS professionals who are doing and being evidence

based in their practice will be well placed and valued for their expertise.

They will be well equipped to influence decision makers, grow in maturity, and

contribute to the evidence base of the profession. The EBLIP model must be

strengthened with an explicit step that promotes actively contributing to the

evidence base for the betterment of libraries and the profession.

Acknowledgements

The author

acknowledges and pays respect to the people of the Yugambeh

nation on whose land this work was created.

References

Appleton, L.

(2021). Editorial – Academic librarians and engaging with scholarship. New

Review of Academic Librarianship, 27(2), 145–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2021.1944747

Booth, A.

(2004). Formulating answerable questions. In A. Booth & A. Brice (Eds.), Evidence-based practice for information

professionals: A handbook (pp. 61–70). Facet

Publishing.

Booth, A.

(2009). EBLIP five-point-zero: Towards a collaborative model of evidence-based

practice. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(4), 341–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00867.x

Crumley, E.,

& Koufogiannakis, D. (2004). Disseminating the

lessons of evidence based practice. In A. Booth & A. Brice (Eds.), Evidence-based practice for information

professionals: A handbook (pp. 138–143). Facet

Publishing.

Drabinski, E. (2019).

What is critical about critical librarianship? Art Libraries Journal, 44(2), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/alj.2019.3

Haddow, G.

(1997). The nature of journals of librarianship: A review. LIBRES: Library and Information Science Research, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.32655/LIBRES.1997.1.4

Hallam, G.

(2018). Being evidence based makes sense! An introduction to Evidence Based

Library and Information Practice (EBLIP). Bibliothek

Forschung und Praxis, 42(3), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1515/bfp-2018-0067

Howard, Z.,

& Davis, K. (2011). From solving puzzles to designing solutions:

Integrating design thinking into evidence based practice. Evidence Based

Library and Information Practice, 6(4), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8TC81

Howlett, A.

(2018). Time to move EBLIP forward with an organizational lens. Evidence Based Library and Information

Practice, 13(3), 74–80. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29491

Koufogiannakis, D. (2013). How academic librarians use evidence in

their decision making: Reconsidering the Evidence Based Practice Model

[Doctoral dissertation, Aberystwyth University]. Aberystwyth Research Portal. http://hdl.handle.net/2160/12963

Koufogiannakis, D., &

Brettle, A. (Eds.). (2016). Being

evidence based in library and information practice. Facet Publishing.

Koufogiannakis,

D., & Crumley, E. (2006). Research in librarianship: Issues

to consider. Library Hi Tech, 24(3),

324–340. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378830610692109

Lamond, H.,

& Fields, A. (2020). Evidence based library and information practice: A New

Zealand perspective. New Zealand Library

and Information Management Journal, 57(2), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12725387

Nguyen, L.

C., & Hider, P. (2018). Narrowing the gap between LIS research and practice

in Australia. Journal of the Australian Library and Information Association,

67(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2018.1430412

Partridge, H., Edwards, S. L.,

& Thorpe, C. (2010). Evidence-based practice: Information professionals’

experience of information literacy in the workplace. In A. Lloyd & S. Talja (Eds.), Practising information literacy: Bringing theories of

learning, practice and information literacy together (pp. 273–297). Centre for Information

Studies. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-1-876938-79-6.50013-3

Thorpe, C.,

& Howlett, A. (2020). Understanding EBLIP at an organizational level: An

initial maturity model. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 15(1),

90–105. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29639

Todd, R. J.

(2015). Evidence-based practice and school libraries: Interconnections

of evidence, advocacy, and actions. Knowledge Quest, 43(3), 8–15. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1048950.pdf