Research Article

The Role of Institutional Repositories in the Dissemination and Impact of Community-Based Research

Cara Bradley

Research & Scholarship Librarian

University of Regina Library

Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada

Email: cara.bradley@uregina.ca

Received: 17 May 2021 Accepted: 7 Aug. 2021

![]() 2021 Bradley. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2021 Bradley. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Data Availability: Bradley, C. (2021). Canadian

community-based research unit outputs, 2010-2020 (V1) [Data]. Scholars Portal Dataverse. https://doi.org/10.5683/SP2/GYVKN6

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29972

Abstract

Objective – The goals of this study were to 1) characterize the quantity and

nature of research outputs created by or in cooperation with community-based

research units (CBRUs) at Canadian universities; 2) assess dissemination

practices and patterns with respect to these outputs; 3) understand the current

and potential roles of institutional repositories (IRs) in disseminating

community-based research (CBR).

Methods – The

researcher consulted and consolidated online directories of Canadian

universities to establish a list of 47 English language institutions. Working

from this list of universities, the researcher investigated each in an attempt

to identify any CBRUs within the institutions. Ultimately, these efforts

resulted in a list of 25 CBRUs. All but 1 of these were from universities that

also have IRs, so 24 CBRUs were included for further analysis. The researcher

visited the website for each CBRU in February 2021 and, using the data on the

site, created a list of each project that the CBRU has been involved in or

facilitated over the past 10 years (2010-2020). An Excel spreadsheet was used

to record variables relating to the nature and accessibility of outputs

associated with each project.

Results – These

24 CBRUs listed 525 distinct projects completed during the past 10 years

(2010-2020). The number of projects listed on the CBRU sites varied widely from

2 to 124, with a median of 13. Outputs were most frequently reports (n=375,

which included research reports, whitepapers, fact sheets, and others), with

journal articles (n=74) and videos (n= 42) being less common, and other formats

even less frequent. The dissemination avenues for these CBRU projects are

roughly divided into thirds, with approximately one third of the projects’

results housed on the CBRU websites, another third in IRs, and a final third in

“other” locations (third party websites, standalone project websites, or not

available). Some output types, like videos and journal articles, were far less

likely to be housed in IRs. There was a significantly higher deposit rate in

faculty or department-based CBRUs, as opposed to standalone CBRUs.

Conclusion – The results of this study indicate that academic libraries and their

IRs play an important role in the dissemination of CBR outputs to the broader

public. The findings also confirm that there is more work to be done; academic

librarians, CBRU staff, and researchers can work together to expand access to,

and potentially increase the impact of, CBR. Ideally, this would result in all

CBRU project outputs being widely available, as well as providing more

consistent access points to these bodies of work.

Introduction

Most

Canadian universities, like similar institutions worldwide, have a tripartite

mandate that includes teaching, research, and service. Some researchers and

their institutions have devoted considerable time and resources to conducting

CBR, an undertaking that combines research and service in an effort to investigate

pressing community issues. CBR (with variations known by names like

community-based participatory research, community-engaged research,

collaborative research, and others) is widely viewed as one way that

universities can build relationships with and have an impact on their wider

communities, and be “of and not just in their community” (Watson, 2003, as

cited in Macpherson et al., 2017, p. 298).

CBR

in its truest form is a partnership between academics and community members to

investigate research topics of common concern. Ideally, CBR sees the

involvement of community partners throughout the entire research process, from

identifying the question or problem, through designing the research study and

collecting data, and on to sharing and disseminating the research findings

widely (not only among other academics, but crucially among the community

participants in the research and the wider population). By addressing real,

local concerns, CBR has the potential to improve the lives of residents. Even a

cursory look at the titles of CBR outputs reveals that many focus

on important social justice issues and that a number of individuals and groups

stand to benefit from broad sharing of these research findings. Access to these

research results or “informational justice” (Mathiesen,

2015) is an important consideration in ensuring that CBR achieves its greatest

possible impact.

Widespread

dissemination has frequently been highlighted as an area where CBR falls short,

but there have been few efforts to objectively assess what happens to CBR

outputs upon completion, and no studies on how academic libraries (who

routinely assist researchers with dissemination to academic audiences)

contribute to CBR dissemination efforts. Thus, the goals of this study were to

1) characterize the quantity and nature of research outputs created by or in

cooperation with CBRUs at Canadian universities; 2) assess dissemination

practices and patterns with respect to these outputs; 3) understand the current

and potential roles of IRs in disseminating CBR.

Literature Review

Several

studies highlight both the importance and difficulty of communicating the

results of CBR beyond academia. Most of these studies question key stakeholders

in CBR to collect their assessments of the challenges and state of CBR

communication. Bodison et al. (2015) provide an

example of this type of work. They conducted a discussion forum with multiple

stakeholders in CBR and found that “research findings are rarely meaningfully

communicated back to those who participated, if communication about the

findings occurs at all” (Bodison et al., 2015, p.

817). Such studies are useful and provide direction for improvements, but they

do not provide objective assessments of current CBR dissemination practices.

One exception is Chen et al. (2010), who conducted a systematic review of CBR

publications to assess efforts in disseminating findings beyond scholarly

journal articles, in order to find out what is really happening regarding wider dissemination. They found that

despite the fact that widespread dissemination of findings is a key tenet of

CBR, “substantial challenges to dissemination remain” (Chen et al., 2010, p.

377). To date, this is one of very few studies assessing what actually happens

to CBR results once projects are concluded. Even less has been written about

what role academic libraries might play in the dissemination of CBR. The most

relevant literature investigates library contributions to increasing research

impact within the academy. This is supplemented by more recent work that has

started to consider the role of academic libraries in dissemination outside of

the academy and contributions to public engagement and the common good.

Recent

years have seen academic libraries expand from primarily supporting teaching

and learning in their universities, to an increased emphasis on support for

faculty and graduate student research. As recently as 2011, MacColl

and Jubb noted that “it is hard to avoid the

conclusion that libraries in recent years have been struggling to make a

positive impact on the scholarly work of researchers, but having relatively

little effect” (p. 5). This is gradually changing, driven in no small part by

increasing requirements around national research impact assessment initiatives

like the Research Excellence Framework requirements in the UK and the impact

assessment requirement as a component to the Excellence in Research for

Australia (ERA) national framework. Librarians are increasingly called upon to

assist their organizations in demonstrating the impact of their research

through using conventional and alternative (“alt”) metrics. Corrall

et al. (2013) surveyed academic librarians in four countries to better

understand the scope and nature of their support for research activities in

their institutions. The results confirmed that national research assessment

exercises had breathed new life into bibliometric services in many libraries

and that “the focus of bibliometric activity . . . has shifted from collection

development to research evaluation and impact assessment for individual

researchers, academic groups, organizational units and whole institutions” (Corrall et al., 2013, p. 666). They concluded, though, that

there remain “significant opportunities for further engagement” in this type of

work (Corrall et al., 2013, p. 666).

In

2014, Kennan et al. revisited their results to further analyze the skills

required for librarians to succeed in supporting both research impact

assessment and research data management. They found that many librarians

reported needing additional training and skills development to undertake this

work with confidence. Nicholson and Howard (2018), in their study of the gap

between core competencies required for research support work (as evidenced in

position postings) and the skills of library and information professionals,

similarly found that “it would be beneficial to build upon the skillsets of

current and new LIS professionals” regarding research engagement and impact

topics (p. 144).

Given

et al. (2015) looked more specifically at the need to disseminate scholarly

research and expand its impact to those outside of the academy; they

interviewed 10 Australian academics in an effort to better understand their

conceptions of research impact in both academic and non-academic settings, to

gain participants’ insight into “existing or needed university-based supports

to foster societal engagement” (p. 4). They found that academics generally felt

ill-equipped to disseminate their work beyond traditional channels (scholarly journals

and conferences) and these academics “did not identify any existing library

supports that could be applied to their work in the societal impact space”

(Given et al., 2015, p. 6). The researchers encouraged further efforts,

commenting that “academic librarians and information science researchers can be

proactive . . . to ensure that researchers and institutions are well-informed

and well-prepared to engage with their communities in appropriate and

productive ways” (Given et al., 2015, p. 8).

One

of the most common ways for researchers to extend the impact of their work

beyond the academy is through the creation of research outputs that differ from

traditional journal articles and scholarly books. More accessible outputs like

whitepapers and policy documents are increasingly likely to reach and impact

policy makers, just as videos, recordings, fact sheets, websites, and blog

posts may be more easily accessed and readily understood by the general public.

Many of these outputs fall under the broad category of grey literature and some

researchers have started to investigate the role of IRs in collecting,

providing access, and preserving these outputs. Searle notes that “librarians

involved in scholarly communication must move quickly beyond a limited set of

formal publication types towards a wide range of more complex and arguably more

at-risk research outputs” and that “grey literature struggles to find a place

in library strategies despite the evidence of its high value to communities

outside academia” (Agate et al., 2017, p. 2). The following year, Marsolek et al. (2018) conducted a study of the

discoverability of grey literature in IRs and commercial databases; they found

that 95% of the 115 IRs included in their study contained grey literature, but

concluded that only 63% of IRs seemed to be actively working to collect it (p.

15). Theses and dissertations were the most commonly collected grey literature

found in IRs, while others like technical reports, working papers, blogs,

standards, and protocols were much less likely to be included. Marsolek et al. (2018) concluded that:

The marriage between IRs and grey

literature could elevate the value of IRs to the research community. IRs could

make a substantial difference in ensuring grey literature’s preservation,

increasing its reach, and, in many cases, providing a form of legitimacy to

these items published outside traditional realms. (p. 17)

Moore

et al. (2020) explored how use of IRs to provide access to grey literature can

also help universities increase public engagement and achieve community service

goals; they saw an important role for IRs in the “recognition, dissemination,

and preservation of the outputs of community-based research”, outputs which are

often grey literature (p. 117). Moore et al. (2020) state how a repository

containing grey literature produced during the course of CBR helps the

university to “present a more holistic picture of its community partnerships

and institutionalize public

engagement into something much more integral and essential to campus (and

local) culture” (p. 117). They describe how the repository at the University of

Minnesota became a “conduit between campus units and community partners” (Moore

et al., 2020, p. 117). In the process, the IR began to “play a strategic role

in public engagement . . . by acting as a common good to showcase,

contextualize, disseminate, preserve, and institutionalize this content” and

came to “support the research, teaching, and outreach mission of an engaged

campus, provide a service as a public good, and contribute to an informed

citizenry in society” (Moore et al., 2020, p. 126). This echoes Makula’s (2019) description of the University of San

Diego’s repository as moving from its position as “primarily a platform, a

system, or a service” to becoming “a bridge between the University of San Diego

and the outside world, an instrument helping to build and nurture

institutional-community relationships, foster collaboration, and cultivate good

will” (para. 12).

Heller

and Gaede’s (2016) work expands the notion of the IR as a common good by

emphasizing that “libraries must move beyond pragmatic justification for

institutional repositories . . . [and] understand their work in the context of

social justice, lest they become complicit in unjust scholarly communication

systems” (p. 3). They articulate a “social justice impact metric” based on

search engine access to social justice-related repository content, as well as

access to all repository content by developing countries, to express the social

justice impact of IRs (Heller & Gaede, 2016, p. 3). They offer this metric

as a way for other librarians to assess their own open access activities in

terms of their level of success in contributing to the public good, by reaching

members of the public who would not otherwise have access to this important

content. Perhaps even more important than the metric they offer, though, is the

insight that:

Open access to the scholarly and

creative output of our institutions contributes a vital academic good insofar as

prestige and reputation are concerned, but the social good is something

extraordinary and should excite us more. In reclaiming our role as facilitators

of democratic discourse, we demonstrate the change we believe in and live out

our bibliography. (Heller & Gaede, 2016, p. 15)

Mathiesen (2015) offers

the theory of “information justice” as a framework for better understanding the

contributions of library work to social justice. She describes “informational

justice” as a facet of social justice concerned with people as “seekers,

sources, and subjects of information” (p. 199). She notes that:

What makes informational justice of

central concern, and thus why libraries and other information services are

particularly important, is the fact that informational injustice produces and

reinforces other forms of social injustice, while information justice

undermines systems of social injustice. Indeed, informational justice serves as

a good proxy for social justice writ large, because opportunities to receive

and share information are central means for enhancing all aspects of people’s

lives. (Mathiesen, 2015, pp. 204-5)

Mathiesen’s (2015)

elaboration of “iDistributive justice”, which is

terminology for “equitable distribution of access to information” is

particularly relevant when thinking about the library’s role in making CBR more

widely available to those who may benefit from but lack access (p. 207). For

librarians engaged in the many facets of research impact work for institutions,

it is important to ask whether they are doing all they can to extend research

impact to the broader community beyond academia and contribute to informational

justice.

Methods

University

involvement with CBR is difficult to quantify and track. Some is coordinated by

units, either at the department, faculty, or institutional level, that

facilitate partnerships between community organizations and researchers.

Research associated with CBRUs was chosen as the subject of study for this

paper because it provides a manageable starting point for exploring the nature

and accessibility of CBR outputs.

Even

this approach is not without its challenges. The language for referring to this

type of research varies and seems to be in transition, including names such as

“research shop”, “community-based research”, “community-engaged research”, and

“community-based participatory research”, among others. As well, there is no

comprehensive list of department, faculty, or university CBRUs in Canadian

universities. As such, the researcher consulted and consolidated online

directories of Canadian universities to establish a list of 47 English language

institutions. Universities or colleges that are smaller affiliates of larger

institutions were excluded based on difficulties distinguishing their

contributions from those of their larger partner or parent organizations.

Working

from this list of universities, the researcher investigated each in an attempt

to identify any CBRUs within the institution. This involved viewing lists of

research centres and institutes on each university’s

webpage, searching these institutional webpages for variations of

“community-based research”, and conducting Google searches combining this

concept with the name of each institution. Multi-institution CBRUs (for

example, Nova Scotia’s CLARI) were excluded due to the anticipated difficulty

of tracking outputs in the repositories of specific institutions at later

stages in the research process. Ultimately, these efforts resulted in a list of

25 CBRUs. All but one of these were from universities that also have IRs, so 24

CBRUs were included for further analysis.

The

researcher visited the websites for each CBRU in February 2021 and used the

data on the websites to create a list of projects that the CBRUs had been

involved in or facilitated over during the past 10 years (2010-2020). The

researcher used an Excel spreadsheet to record variables relating to the nature

and accessibility of outputs associated with each project. These variables

included:

-

Type

of outputs (document, video, website, and others)

-

Availability

of output in its entirety (i.e., full-text, entire video, journal articles, and

others) on:

o

CBRU

websites

o

IRs

(the names of projects and lead researchers were also searched in the IRs, even

in instances where there was no link to the IR from the CBRU webpage)

o

Third

party websites

o

Dedicated

project websites

The

researcher then analyzed the findings to learn more about the dissemination of

CBR and, in particular, the role of the IR in disseminating the results of this

research.

Results

As

mentioned above, this methodology produced a list of 47 English-language

Canadian universities, within which 24 CBRUs were identified in institutions

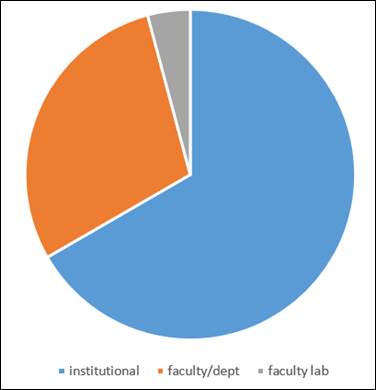

that also have IRs. As shown in Figure 1, these CBRUs were housed in 19

institutions, with some having 2 distinct CBRUs. Sixteen of the CBRUs were at

the institutional level (that is, not located within a specific faculty or

department); 7 were housed within faculty or departments, and 1 was a faculty

member’s laboratory.

Between

them, these 24 CBRUs listed 525 distinct projects completed during the past 10

years (2010-2020). Projects that were clearly still underway or in progress

were excluded from the analysis, given they could not yet be expected to have

produced outputs for analysis. The number of projects listed on the CBRU sites

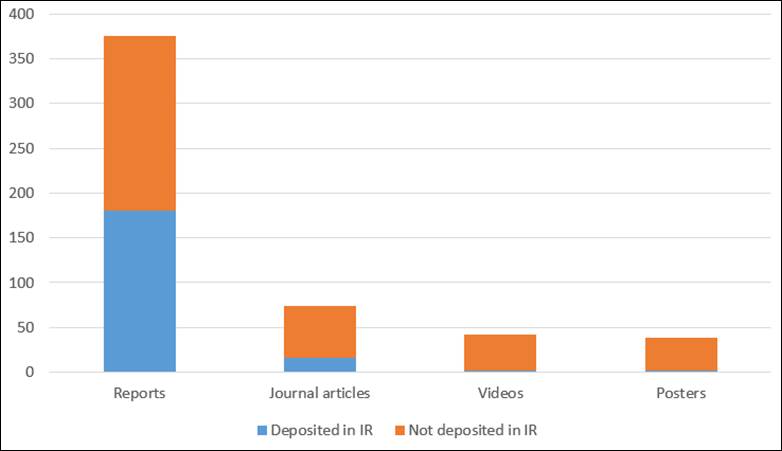

varied widely from 2 to 124, with a median of 13. Figure 2 shows a breakdown of

outputs by type. The number of outputs exceeds the number of projects because

some projects produced more than one output type.

As

Figure 2 clearly shows, reports (which includes research reports, whitepapers,

fact sheets, and others) was the largest category of outputs (n=375). “Unique”

(n=13) includes output types that only appeared once across all the data (e.g.,

electronic book, blog, storytelling event, among others), while “unclear”

(n=36) includes projects whose description suggests that there was an output

generated, but its nature is not specified nor is the work provided.

Figure 1

Type of community-based research unit.

Figure 2

CBRU outputs by type.

After

characterizing the types of outputs emerging from CBRUs, the study sought to

assess if and how research outputs were made accessible to interested readers.

Some outputs were available in more than one place (e.g., IR and CBRU

websites), so the total output locations in Figure 3 exceed the 525 projects

included in the analysis. The “CBRU website” includes outputs (n=197) available

in their entirety (full report, entire project video, and others) on the units’

webpages. “Institutional repository” similarly indicates that an entire output

has been deposited in the IR (n=193). “Third-party website” describes instances

where the CBRU websites link to a third-party website where the research output

can be found (n=104). “Project website” indicates that the CBRU site links to a

stand-alone website, created to share the results of that particular project

(n=19). “Available for purchase” refers to instances where the CBRU websites

either link to (n=22) or provide citations without links (n=9) to a journal

article that requires an institutional subscription or personal purchase to

access the research output. Sixty-five projects are categorized as “Not

available” because the CBRU websites suggest that there have been outputs from

the research, but there is no access information provided or the only method

provided is a dead link.

Figure 3

Dissemination of research outputs.

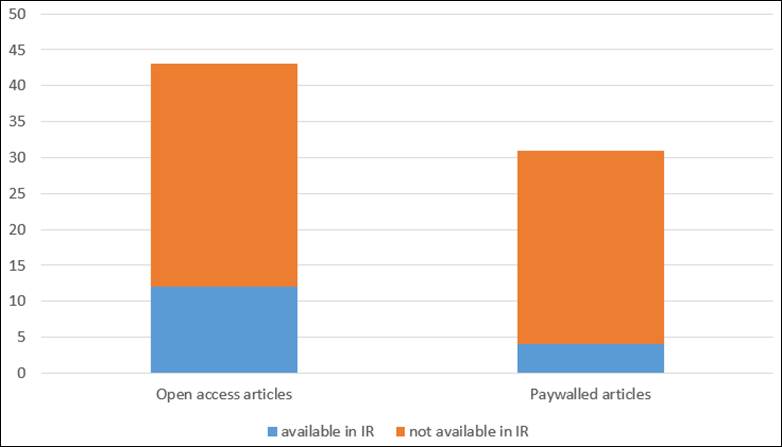

Figure 4

Journal articles by publication type and IR

availability.

Third-party

websites figure prominently in the dissemination of research outputs from the

CBRUs, with 104 of the projects (19.8%) using this as a means of sharing

results. These third- party sites can be divided into three broad categories:

video sites like YouTube and Vimeo (37 videos), journal websites (74 articles),

and websites of partner or funding organizations that contain the research

outputs (n=24). Another 19 projects (3.6%) have separate project websites to

share results. Importantly, in terms of access, there were 10 dead links from

projects listed on CBRU websites to third-party or project websites.

Outputs

were not freely available for 72 of the projects (13.7%). This included 65

projects that indicated reports or other outputs existed and either did not

provide access or a link, or else provided a dead link, as well as 7 for which

outputs could only be viewed by purchasing access to paywalled journal articles

that were not available in the corresponding IRs. Overall, there were 31

paywalled articles identified as sites for research output, but most

supplemented other output methods and did not therefore impede access to the

outcomes of the project, except for the 7 highlighted above. This compares to

43 open access articles listed as outputs of these research projects. Figure 4

shows the breakdown of journal articles by publication type, as well as the

portion of each type that are also deposited in the IRs (4/31 or 12.9% of

paywalled articles and 12/43 or 27.9% of open access articles).

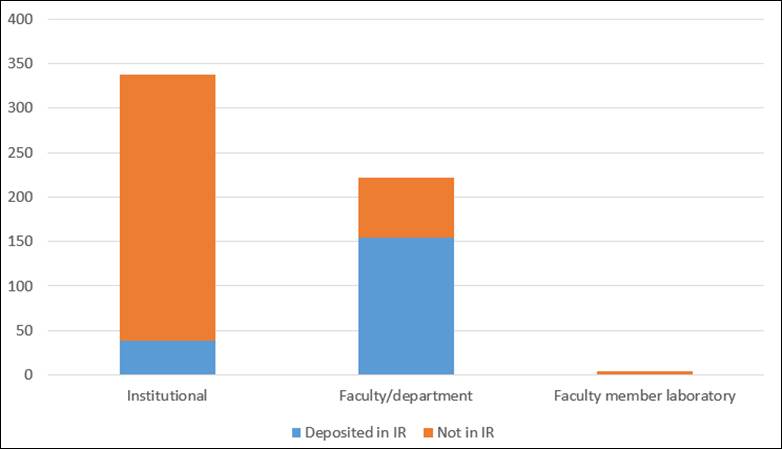

Overall,

a total of 193 (36.8%) of the projects resulted in research outputs than can be

found in the institutions’ repositories. Figure 5 shows that there are some

notable differences in the rates of outputs deposited in IRs when the data were

further broken down. The 7 faculty or department-based CBRUs had an IR deposit

rate of 69.4% (154 of 222 projects), while the institutional-level CBRUs only

had an IR deposit rate of 13% (39 of 299 projects). None of the projects

emerging from the faculty member research laboratories were captured by their

IRs. Thus, although only 7 of the 24 CBRUs (29.2%) were faculty or department

based, they accounted for 154 of the 193 (79.8%) projects for which research

outputs were deposited in IRs.

Figure 5

IR deposit for projects, by CBRU type.

Interestingly,

only 177 of the 193 projects found in IRs contained a link from the CBRU

websites to the relevant repository contents. Thus, the output of 16 projects

(8.2%) are in fact held in IRs but would not be found by readers or researchers

viewing the CBRU websites.

While

36.8% of research outputs from these CBRUs can be found in the corresponding

IRs, Figure 6 shows that the frequency with which these outputs are deposited

varies widely depending on the nature of the output. 48% of reports (n=180)

have been deposited, while the same can be said of 21.6% of journal articles

(n=16). Deposit rates are much lower for items that are not typical Word or PDF

files; only 9.5% of videos (n=2) and 5% of posters (n=2) have been deposited.

Discussion

The

dissemination avenues for these CBRU projects are roughly divided into thirds,

with approximately one third of the project results housed on CBRU websites,

another third in IRs, and a final third in “other” (third party websites,

standalone project websites, or not available). This demonstrates a level of

inconsistency among dissemination practices that would make it difficult for

individuals interested in this type of research to know how to proceed in

locating it. Although posting research outputs on CBRU, third-party, or

standalone websites may aid findability in the short term, sole use of these

sites generates problems over the long term. The problems of “content drift,”

where the contents of webpages change over time and “URL decay” (i.e., URLs no longer

active) have been well-documented (Jones et al., 2016; Oguz

& Koehler, 2016). IRs, by contrast, provide “safe storage, persistent URLs,

backup, and possibly migration if it is needed in the future” and reduce CBRU website

and file hosting workloads (Marsolek et al., 2018, p.

5). Many CBRU-involved outputs remain relevant over the longer term, and

continued access is important for faculty members seeking to include these

materials in promotion and tenure applications.

Figure 6

IR deposits by output type.

There

was also a marked difference in the deposit rate for different output formats.

“Reports” which included Word and PDF text files, were deposited at a much

greater rate than alternative formats like videos and posters, among others.

The reason for this is unclear but warrants further investigation, since

research has shown that some of these alternative formats have the greatest

potential to impact the general public. Possible explanations include IR

collection policies that align with traditional (print) collection policies,

the failure of librarians to actively collect materials in these formats, or

lack of awareness among the campus community (CBRU staff and researchers) that

other formats are also welcome in IRs. It was somewhat surprising that journal

articles emerging from these CBRU projects were not more consistently included

in the IRs (only 21.6% had been deposited), given that the collection of

journal articles has long been a priority for many IRs and many libraries have

developed policies, workflows, and advocacy tools to support journal article

collection.

Cost

was less of an access barrier to CBRU-involved work than expected; while 31

paywalled journal articles emerged from the work of these CBRUs, there were

only 7 cases where this prevented all access to the research findings. The

other 24 paywalled articles were supplemented with freely available reports or

summaries available elsewhere (IR, CBRU site, third-party site, standalone

site). The lack of availability of any findings associated with a research

project was, conversely, more of a problem that anticipated, with 65 (12.4%)

projects providing no information about outputs or providing only a dead link.

There were also instances where the output was available, but findability was

an issue. In several instances, CBRU outputs could only be found in IRs, but

there was no indication on the CBRU site that this was the case. This has

implications for accessibility, as only those who thought to conduct a separate

search of the IR would have access to the full research output. Also

interesting was the discrepancy between the IR deposit practices of

institutional vs. faculty or departmental CBRUs. Faculty or department CBRUs

deposited at a far greater rate than institution-level CBRUs (69.4% vs. 13%).

This large difference warrants further investigation, as it may provide

insights into how deposit rates by institutional CBRUs can be increased. Many

Canadian academic libraries still operate with some variation of a subject

liaison librarian model, usually supplemented by functional positions

(scholarly communications librarian, systems librarian, among others). It would

be valuable to better understand whether the relationship between the subject

liaison librarians and faculty or departmental CBRUs is important to achieving

this relatively high rate of deposit, and how this success could be transferred

to institutional CBRUs, whose staff may not have (or be aware of) a connection

with a subject specialist.

There

were a few instances of institutions that had adopted unique practices of

dissemination that do not fit neatly into the results above, but are relevant

to note as examples of possible approaches to expanding the reach of CBR. The

University of British Columbia’s DTES Portal (https://dtesresearchaccess.ubc.ca) is an

impressive effort to expand access and awareness to research results relevant

to the issues facing Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. The mandate of the DTES

portal differs somewhat from that of the CBRUs included in this study, in that

they aim to collect material of interest to the community regardless of creator

or origin (not necessarily involving academia) and to profile this material in

a standalone database. Their curatorial statement (https://infohub-2019.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2020/07/Curatorial-Statement-2020-Final.pdf), however, also

indicates that they collaborate with the UBC IR in their collection of relevant

UBC research outputs. Many institutions lack the resources to create a

standalone topic repository of this nature, but the DTES Portal does provide a

model that might be embedded within existing IRs. At another institution, the

CBRU website simply links to the relevant section of the IR that lists all of

the CBRU projects (including the full outputs). This means that all CBRU items

are included in the IR, saving the CBRU the work of creating and maintaining a

list of projects and associated outputs. These are examples of different ways for

academic libraries to approach utilizing their IRs to collaborate with CBRUs in

the dissemination of CBR.

There

are some limitations to the methods used in this study. CBRUs represent only a

portion of the CBR undertaken at Canadian universities. It would be useful

conduct a study of researchers doing CBR without the involvement of CBRUs in

order to understand if their dissemination practices differ from those observed

in this study. Another limitation is the reliance on the CBRU websites to

identify projects as well as outcomes. It is possible that some CBRU-involved

projects were not listed on the websites and therefore these outputs were

excluded from the analysis. A future study might reduce this risk by asking

CBRUs to provide a list of all the projects in which they were involved over a

given time frame. Additionally, it is possible that in some instances CBRUs or

researchers have chosen to communicate results to community members in other

ways that would not be captured in this type of study (e.g., a seminar

presenting results to community members or a report sent directly to a

partnering community organization). This would be a suitable way to communicate

with research participants and community stakeholders, but it prevents other

individuals and organizations from benefiting from the results of the research.

Surveys, interviews, or focus groups with CBRU staff and affiliated researchers

might be the best way to supplement the results of this study and deepen

understanding of CBRU research dissemination practices and the role that

academic libraries and their IRs might play in this process.

Conclusion

The

results of this study indicate that academic libraries and their IRs play an

important role in the dissemination of CBR outputs to the broader public. The

findings also confirm that there is more work to be done; academic librarians,

CBRU staff, and researchers can work together to expand access to and

potentially increase the impact of CBR. Ideally, this would result in all CBRU

project outputs being widely available, as well as providing more consistent

access points to these bodies of work. IRs are not, by any means, the entire

solution to the complex issues of CBR dissemination, but their more consistent

use would be one piece of the puzzle. Additional services and supports for CBR

could build upon the relationships established in implementing such a service,

providing a way for academic librarians to contribute to the common good and

amplify the social justice efforts of their universities. This work is one way

to “reclaim . . . our role as facilitators of democratic discourse” (Heller

& Gaede, 2016, p. 15) and contribute to the realization of what Mathiesen (2015) termed “informational justice” (p. 199).

References

Agate, N.,

Clement, G., Kingsley, D., Searle, S., Vanderjagt,

L., Waller, J., Schlosser, M., & Newton, M. (2017). From the ground up: A

group editorial on the most pressing issues in scholarly communication. Journal

of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication, 5(1), eP2196. https://doi.org/10.7710/2162-3309.2196

Bodison, S. C., Sankaré, I., Anaya, H., Booker‐Vaughns,

J., Miller, A., Williams, P., & Norris, K. (2015). Engaging the community

in the dissemination, implementation, and improvement of health‐related

research. Clinical and Translational

Science, 8(6), 814-819. https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.12342

Chen, P. G.,

Diaz, N., Lucas, G., & Rosenthal, M. S. (2010). Dissemination of results in

community-based participatory research. American

Journal of Preventive Medicine, 39(4),

372-378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.021

Corrall, S., Kennan, M.

A., & Afzal, W. (2013). Bibliometrics and research data management

services: Emerging trends in library support for research. Library Trends,

61(3), 636-674. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2013.0005

Given, L. M.,

Kelly, W., & Willson, R. (2015). Bracing for

impact: The role of information science in supporting societal research impact.

Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 52(1),

1-10. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2015.145052010048

Heller, M.,

& Gaede, F. (2016). Measuring altruistic impact: A model for understanding

the social justice of open access. Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly

Communication, 4(0), eP2132. https://doi.org/10.7710/2162-3309.2132

Jones, S. M.,

Van de Sompel, H., Shankar, H., Klein, M., Tobin, R.,

& Grover, C. (2016). Scholarly context adrift: Three out of four URI

references lead to changed content. PLoS

ONE, 11(12), e0167475. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167475

Kennan, M. A., Corrall, S., & Afzal, W. (2014). “Making space” in

practice and education: Research support services in academic libraries. Library

Management, 35(8/9), 666-683. https://doi.org/10.1108/LM-03-2014-0037

MacColl, J., & Jubb, M. (2011). Supporting

research: Environments, administration and libraries. https://www.oclc.org/content/dam/research/publications/library/2011/2011-10.pdf

Macpherson, H.,

Davies, C., Hart, A., Eryigit-Madzwamuse, S.,

Rathbone, A., Gagnon, E., Buttery, L., & Dennis, S. (2017). Collaborative

community research dissemination and networking: Experiences and challenges. Gateways: International Journal of Community

Research and Engagement, 10,

298-312. https://doi.org/10.5130/ijcre.v10i1.5436

Makula, A. (2019).

“Institutional” repositories, redefined: Reflecting institutional commitments

to community engagement. Against the Grain, 31(5). https://www.charleston-hub.com/2019/12/v315-institutional-repositories-redefined-reflecting-institutional-commitments-to-community-engagement/

Marsolek, W. R., Cooper,

K., Farrell, S. L., & Kelly, J. A. (2018). The types, frequencies, and

findability of disciplinary grey literature within prominent subject databases

and academic institutional repositories. Journal of Librarianship and

Scholarly Communication, 6(1),

eP2200. https://doi.org/10.7710/2162-3309.2200

Mathiesen, K. (2015).

Informational justice: A conceptual framework for social justice in library and

information services. Library Trends 64(2), 198-225. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2015.0044

Moore, E. A., Collins, V. M., & Johnston, L. R. (2020).

Institutional repositories for public engagement: Creating a common good model

for an engaged campus. Journal of Library Outreach and Engagement 1(1),

116-129. https://doi.org/10.21900/j.jloe.v1i1.472

Nicholson, J.,

& Howard, K. (2018). A study of core competencies for supporting roles in engagement

and impact assessment in Australia. Journal of the Australian Library and

Information Association, 67(2), 131-146. https://doi.org/10.1080/24750158.2018.1473907

Oguz, F., &

Koehler, W. (2016). URL decay at year 20: A research note. Journal of the

Association for Information Science and Technology 67(2), 477-479. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23561