Introduction

The concept of

career is changing (Lyons, et al., pp. 9–10), and as working professionals

become more mobile and flexible in their definitions of a career, employers

must learn to meet their needs in order to engage a motivated and experienced

workforce. Academic librarians and libraries are no exception. Librarians

wrestle with questions like how they bring their authentic selves to work, how

they understand work and life balance throughout their careers, and how they

perceive career advancement, and at what time. To meet the needs and

expectations of their staff, library administrators must ask how to continue to

retain a pool of driven and satisfied professionals, how to continue to support

librarians as their needs change throughout their careers, and how to create

workplace cultures that offer flexibility and space in support of a diverse

workforce.

This study is an

application of Mainiero and Sullivan’s Kaleidoscope

Career Model. The model uses three phases—Authenticity, Balance, and

Challenge—as a non-linear approach to understanding the mapping of career

trajectories (Figure 1). In the Authenticity phase, professionals have a need

to be genuine and to act in ways congruent with their values. In the Balance

phase, they desire a more balanced personal life. In the Challenge phase, they

seek exciting, stimulating work. Professionals can be in one or several of the

phases at any given time and can move through the phases as the circumstances

and motivating forces in their lives change. For example, while a professional

may start their career in the Challenge phase, later in life they may find

themselves more strongly identifying with Balance or Authenticity before ending

their career back in Challenge.

Figure 1

Kaleidoscope career

model.

Mainiero and Sullivan (2006a) argue “because most

organizations have not acted, individual workers have acted instead. Women and

men are working within and outside corporate boundaries to better blend their

own needs to authenticity, balance, and challenge. These men and women are

making adjustments to their careers to find a regression line that balances

work and family. They are developing new definitions of success” (p. xii).

Though not in the corporate world, academic librarians, too, must grapple with

the impact of economic background, age and ageism in the workplace, gender

identity, care-giving roles, absence of diversity, ableism, and mental health

when determining how best to shape their careers.

In this

female-dominated profession, understanding how women perceive their career

trajectories will help administrators and colleagues determine how to provide

flexible organizational cultures to support their work. Women’s professional

lives are less often characterized by a linear trajectory. Based on the

findings, this study examines how academic librarians conceive of and perceive

their career path trajectories as they relate to their overall sense of

satisfaction with their careers to date and their feelings of support from

their employers.

The initial

findings of this study, drawn from 433 survey responses, suggest that for those

participants who most strongly identify their current career phase as one of

Authenticity, they’re intrinsically motivated by values and sense of “fit”

within their library or the profession. For those who strongly identify with

Challenge, they’re extrinsically motivated by traditional rewards, such as

higher salary and more responsibilities. Intertwined within each of these two

phases is Balance, as the characteristics of that phase heavily impact how

academic librarians perceive their overall career paths. Applying the

Kaleidoscope Career Model in the academic library context enables practitioners

to equip their profession with the language and data to describe themselves as

well as provide an opportunity for self-reflection. As a result, we can better

understand how perceptions of career trajectory impact the industry and its

ability to retain talent.

Literature Review

There exists a

gap in the literature addressing career path changes. This literature review is

divided into a discussion of career progression, a discussion of the increasing

demand for a flexible workforce in response to changing expectations in higher

education, and a discussion of job satisfaction. The literature that explores

these areas focuses almost exclusively on different phases in one’s career,

with the assumption of a linear or stagnant progression into management roles.

While some of the work presented here explores these issues, little research in

libraries has focused on cyclical or nonlinear progression. This study

addresses this gap in the literature through the application of Lisa Mainiero and Sherry Sullivan’s Kaleidoscope Career Model.

Career Progression

In their book The

Opt-Out Revolt: Why People are Leaving Companies to Create Kaleidoscope Careers,

Mainiero and Sullivan (2006a) argue creating adaptive

career paths have fallen to employees because most organizations have not proactively

developed such structures of support. Their study included survey instruments

and interviews with men and women of different generations and industries.

Based on the data they collected, we developed a new framework for conceiving

of career trajectories. They define the Kaleidoscope Career Model as “a career

created on your own terms, defined not by a corporation but by your own values,

life choices, and parameters. Like a kaleidoscope, your career is dynamic and

in motion” (p. 11). The authors go on to argue that “as your life changes, you

can alter your career to adjust to those changes rather than relinquishing

control and letting a corporation dictate your life for you” (p. 111). Their

research revealed that “for men the prospect of a linear career within the same

firm or industry is still highly valued” (p. 107). By contrast the authors

argue “for women, a ‘career’—often defined as a series of interrupted jobs,

transitions, and shifts—cannot be separated from a larger understanding of

their lifestyle priorities” (p. 107). Mainiero and

Sullivan conclude with an analysis of the impact of people’s changing

perceptions of their career trajectories on industry: “For employers,

understanding the importance of the Kaleidoscope Career is critical . . . Until

now, career paths and succession plans within corporations have [not] been

based . . . on the . . . (challenge-balance-authenticity) Kaleidoscope Career

pattern that characterizes most women” (p. 153). The study presented here

employed the Kaleidoscope Career Model survey tool and explores how the field

of academic librarianship complements or complicates the findings in

professions writ large.

Two years after

they completed their book, Sullivan and Mainiero

(2008) published an article aiming to provide suggestions for reconsidering

human resource development programs with women’s career trajectories in mind.

They argue that by mid-career the women in their study were predominantly

concerned about the issue of balance (p. 36). The authors underscore the ways

in which women evaluate opportunities and make decisions, through the lens of

relationalism (p. 37). Drawing on their Kaleidoscope Career Model career

phases, they argue that to meet women’s needs and fit within their framework

for decision making, organizations should consider how women perceive their

current career phase. When working with those in the Authenticity phase,

organizations should focus on corporate social responsibility and company

efforts to promote total wellness in mind, body, and spirit. Organizational

mission should align with women’s personal values and promote ethics and values

(p. 38). By contrast when working with a woman in the Balance phase,

organizations should reward actual performance, regardless of “face time” in

the office, and create actual “family friendly” programs that consider needs

outside of work (pp. 39–40). Finally, for those women in the Challenge phase,

the authors argue organizations should create equitable access to challenging,

meaningful job assignments and training opportunities and should design career

development programs with opportunities (pp. 40–41). These recommendations

highlight the need to find solutions that fit with individual needs and goals,

rather than treat one’s workforce as a monolith. Based on the data presented in

this study, librarians have similar unmet needs and desire differing levels and

systems of support from their organizations throughout the lifecycle.

Applying Mainiero and Sullivan’s (2006a, 2008) work to the field of

health care with nurses in Australia, O’Neill and Jepson (2017) conducted a

two-phase study to better understand the interplay of women's Kaleidoscope

career intentions and life roles. They found “some women seek to transform

their worker and leisure life roles as they desire authenticity in their life

and will pursue paid and unpaid work as well as leisure activities to do so”

(p. 971). Volunteer work was one example of the kind of unpaid work these women

might pursue. Based on their data, the authors conclude “individuals with a

high leisure life role commitment may seek authenticity in their late career

and want to engage in leisure life roles that provide them with internal

fulfilment and satisfaction” (p. 973). Surprisingly, the authors found that

women seeking balance struggle more when caring for aging parents than when

caring for children. Women also seemed to continue to pursue challenging work

late into their career. These women may have fewer commitments to non-work life

roles, such as caregiving or leisure pursuits than others in their study. The

authors stressed the importance of considering the impact and flux of care

responsibilities and other non-work life pursuits throughout the life cycle

when recruiting and retaining women nurses. Furthermore, they underscored the

importance of providing both organizational support for evolving needs, and the

role governmental programs play in women’s ability to successfully navigate

care duties. Published in 2017, this article is one of the first to apply the

Kaleidoscope Career Model to a female-dominated profession, which in that

regard is similar to librarianship.

Meeting the Demand for a Flexible Workforce

Narrowing down

to the field of librarianship within higher education, Maggie Farrell (2013)

highlights the changing nature of career progression in her article, “Lifecycle

of Library Leadership.” Farrell contends “a librarian might move from a

management position to a non-management position and then to a high-level

leadership position. Our organizations are far more fluid today, challenging us

to rethink how an individual progresses within libraries” (p. 257). As Farrell

argues, academic libraries have continued to experiment with non-traditional

organizational hierarchies and job duties. She states “one view of leadership

development is that you progress from a position to a supervisor to a manager

to a leader. Another perspective is that positions change and individuals

develop their skill sets but not necessarily in a linear fashion” (p. 264). Farrell’s

work does not include data indicating the experiences of those whose careers

proceed in a nonlinear path.

Though Farrell

acknowledges such a path exists, her discussion of management and leadership

skill acquisition follows traditional assumptions about such senior roles. The

hard and soft skills needed to be successful as first a manager and then, as

Farrell argues, as a leader do not come into play before one prepares to or

enters those advanced positions. Once one has those skills, should a senior

leader choose to enter into a practitioner role again, “you can take these

skills with you . . . Whereas tradition outlined a linear, developing path for

leadership development, our libraries today require aspects of these skills

throughout our organization. Leadership development at all levels of our

libraries will enhance our work” (p. 264). It seems as though Farrell is not

necessarily advocating for leadership skill development at all levels; rather

she recognizes the benefit of taking advantage of those skill sets once a

senior manager returns to a role elsewhere in the organizational hierarchy.

Michael Ridley’s

(2014) work, “Returning to the Ranks,” explores similar benefits to library

organizations as Farrell. He argues for those library deans and administrators

who have term limits or choose to leave those roles and assume duties outside

of library administration within their organization to consider that many

“former chief librarians often have unique and valuable skill sets that can be

exploited” (p. 4). In librarianship, we tend to think of career paths as a

linear progression rather than cyclical. According to Ridley, senior leaders

often feel they experience a “professional de-skilling” as they move into

administration (p. 3). Their work becomes increasingly focused on external

stakeholders, and their peer group shifts from librarians to senior

administrators in other university units. Facilitating this transition requires

overcoming key challenges including how the former leader develops the most

productive relationship with their new boss and the person’s transition to a

new role, which may include a sabbatical or vacation time and—if

applicable—being part of a union again. Moreover, Ridley highlights the dearth

of librarians willing to enter into senior administrative roles and encourages

decision-makers to develop “a more supportive policy and reward structure that

facilitates returning to the ranks [which] might encourage librarians to

explore management and administrative roles without feeling that they are

somehow ‘leaving the profession’” (p. 9). Ridley’s work makes a valuable

contribution to the literature; his recommendations emerge from conversations

with four senior leaders, including himself, who “returned to the ranks” of

librarianship. These lessons learned offer a useful starting point for further

analysis of librarian career paths.

Sources of Motivation and Job Satisfaction

Determining

sources of motivation and job satisfaction are two related areas that impact

one’s career path and form the cornerstone of this study. In their 2009

article, Mallaiah and Yadapadithaya

describe the findings from a survey they distributed to fifteen academic

librarians working at universities throughout Karnataka. Focused on exploring

intrinsic motivation, the authors concluded that library work, itself, and a

sense of personal worth were two drivers. Considering the broader implications

of their work, Mallaiah and Yadapadithaya

argue “motivation is culture specific, industry-specific, and organization-specific

and context or situation-specific in nature” (p. 41). Related to sources of

motivation is job satisfaction.

Authors Adigwe and Oriola (2015) found among Nigerian librarians “with

increased length of service, the importance of job satisfaction decreased for

factors such as self-actualization and conditions of work, but the importance

of pay increased” (p. 782). For those in American academic libraries seeking to

increase their salaries, few pathways exist other than entering formal

leadership and management positions. Kathy Pennell (2010) underscores an

increasing interest in “shifting away from the use of narrowly defined job

descriptions toward more flexible ones that are not skill based but are based

on job roles. The flexibility allows the latitude necessary to provide

opportunities for job rotation or stretch assignments to help develop

high-potential employees” (p. 286). As a result, employees can better meet

their professional and personal needs and goals throughout their careers, while

employers gain a more satisfied and motivated workforce.

This study

contributes to the existing literature in three critical ways. First, no researchers

to date have addressed the evolving needs of practitioners through a lifecycle

model lens. The research presented here builds on Mainiero

and Sullivan’s (2006a) work by applying the model to the academic librarian

context. The Kaleidoscope Career Model provides the library profession and

organizations with an approach through which to critically reflect on their

current practices, values, and support mechanisms. Second, examining the career

paths of those in senior as well as mid-level and entry-level positions in

academic libraries fills a gap in the literature that to date has focused

almost exclusively on senior-level positions. Third, unlike previous analyses

of librarians’ motivations, the conclusions presented here address both

intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

Aims

This study

addresses two interrelated questions: What motivates library professionals in

doing their work, and what can library administrators do to retain and inspire

their staff? Library professionals should have a better understanding of what

motivates them in their work, why they may or may not choose a traditional

career advancement path, and how priorities in their life may shift over time

and change their career perspectives. This study also underscores the important

role library administrators play in understanding the individual motivations of

their staff and supporting their employees with a more holistic approach

throughout their careers. The application of the Kaleidoscope Career Model,

with its Authenticity, Balance, and Challenge phases, is one framework through

which library professionals and administrators can understand how such

motivators could, and likely do, change throughout the lifecycle.

Methods

We adapted the

Kaleidoscope Career Model survey tool (Mainiero &

Sullivan, 2006b) with permission, which was obtained via email from Mainiero and Sullivan. This survey had been validated as

part of the previous research projects Mainiero and

Sullivan conducted. We piloted but did not validate the adapted survey tool.

Following the guidelines in Fink’s (2013) How to Conduct Surveys, we

pilot tested the survey by emailing a link to the adapted survey available

through Qualtrics to seven academic librarians and received feedback from five

people. We made subsequent edits to the survey based on this feedback. Changes

to the tool included briefer terms on the statements of agreement scale and an

adjustment in some language to be less corporate and more congruent with the

academic library work environment. The survey tool included thirty statements

with a five-point scale, allowing participants to express how much they agreed

or disagreed with each statement. The answers to those thirty statements

resulted in the score participants received, indicating which of the three Kaleidoscope

phases they most closely identified with. The remainder of the survey included

questions about how they felt about their results (Appendix), whether they felt

supported by their library administration, if they supervise or want to

supervise, and if they consider themselves a leader or want to be a leader. The

survey also asked several demographic questions related to institutional

affiliation, gender/gender identity, age, and time spent working in the

profession. The questions were a mix of close-ended and open-ended questions.

We developed the survey using Qualtrics, which enabled us to easily capture

participant responses and begin analysis after data collection.

After receiving

approval from the Institutional Review Boards at both the University of

Arkansas and the University of Rochester, we sent a call for participation with

the link to the survey to six library electronic mailing lists via email in

October 2019. The mailing lists included Rare Books and Manuscripts Section of

the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL), Society of American

Archivists, University Libraries section of the ACRL division of the American

Libraries Association (ALA), College Libraries section of the ACRL division of

the American Libraries Association (ALA), and the former Library Leadership and

Management Association division of ALA. The email included an information

letter describing the research project. Participants had one month to complete

the survey. We emailed two reminders as the survey window continued.

Once the survey

closed, we exported initial statistics from Qualtrics to determine the

breakdown of participants by career phase. We reviewed the demographic data and

charts Qualtrics generated and used an open coding method to analyze the qualitative

responses to open ended questions included in the survey. First, we read

through those responses and then identified common words, phrases, and ideas,

which became initial codes. Each of us coded and analyzed each question. We

then shared our analyses with one another for reliability. Once compared, we

worked together to finalize codes for each question based on the context of the

original participant responses. Then we reviewed the codes and determined

themes common in the data. Those themes then informed the discussion and

recommendations shared below.

Results

The results are

interpreted through three categories based on the questions asked in the

survey: participants’ general demographic information, participants’ sense of

administrative support, and participants’ interest in taking on or continuing

in leadership or supervisory roles.

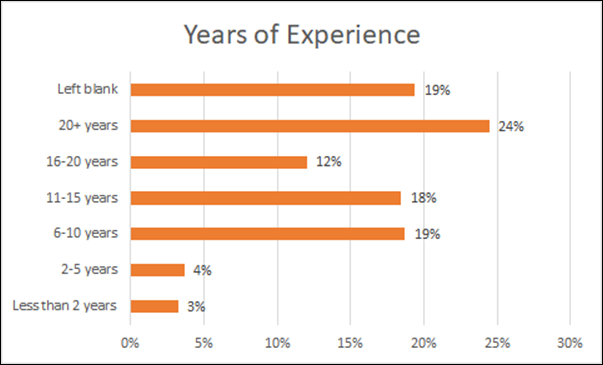

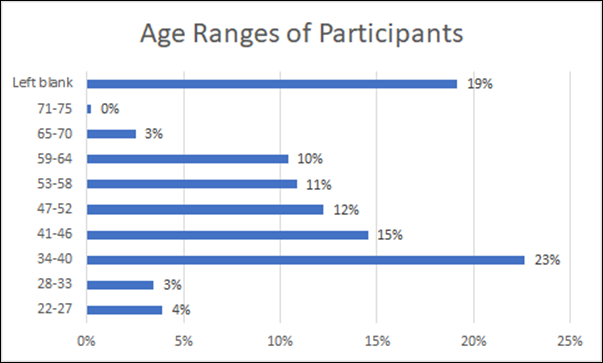

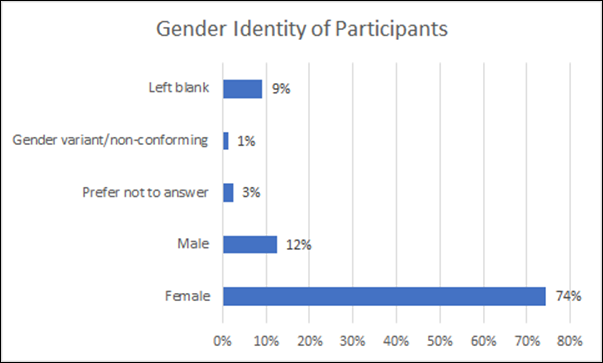

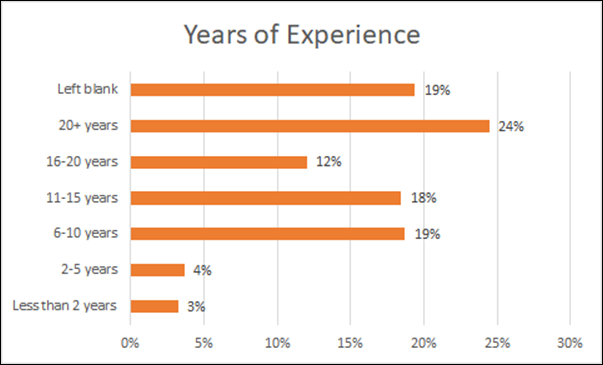

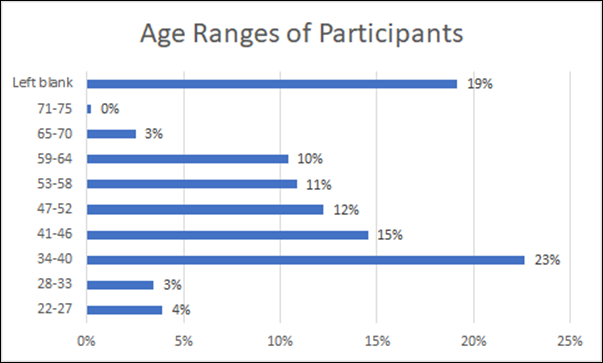

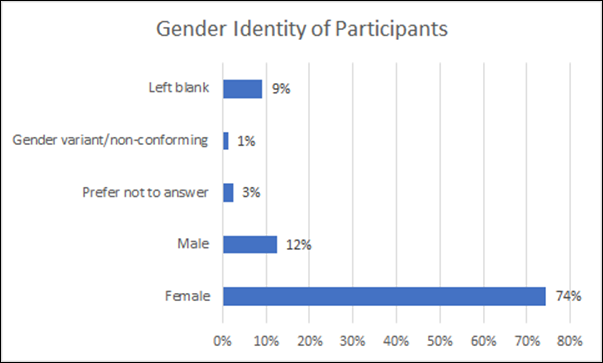

Demographics

A total of 433 people completed the survey. The

majority worked at 4-year doctoral-granting universities (Table 1). Nearly half

of all respondents worked in public services with nearly one-fifth working in

special collections/archives (Table 2). About one-quarter of participants had

twenty or more years of work experience in librarianship (Figure 2). The

largest group of participants (23%) were aged 34–40 (Figure 3). The authors use

the term early-career to refer to those participants aged 22-33; the term

mid-career for those 34-52; and late-career for those 52 and older. The vast

majority (74%) of participants identified as female (Figure 4).

To contextualize the demographics in this study, the

authors exchanged emails with ACRL staff, who provided the 2018 ACRL member

survey data. Of 3,029 respondents, 1% of respondents were aged 18–24 years old,

20% were 25–34, 25% were 35–44, 24% were 45–54, 22% were 55–64, and 9% were 65

and older. Of the respondents, 77% were female (or 2,332.33 respondents), and

20% were male (or 605.8 respondents), with 1% indicated a different gender

identity (or 30.29 respondents) and 2% preferred not to say (or 60.58

respondents). The age and gender demographics in this study were consistent

with the 2018 ACRL survey. The gender demographics were also in line with the

ARL Annual Salary Survey 2018–2019 (Morris, 2019), which found that in U.S. and

non-U.S. libraries, men comprise 36.9% (or 3,541) of staff and women comprise

63.1% (or 6,050 of staff).

Table 1

Institution Type

of Participants

|

Institution

|

Participants

|

|

4-year doctoral-granting

university

|

54% (235 participants)

|

|

4-year masters-granting

university

|

16% (68)

|

|

4-year bachelors-granting

university

|

10% (43)

|

|

Other (e.g., public,

distance, special, nonprofit, seminary, Library of Congress, government

agency, consortium, health sciences, research)

|

5% (24)

|

|

2-year community/vocational

college

|

5% (21)

|

|

Left blank

|

10% (42)

|

Table 2

Functional Area

of Work of Participants

|

Functional

Area

|

Participants

|

|

Public services

|

41% (176 participants)

|

|

Special collections/archives

|

18% (74)

|

|

Administration

|

13% (57)

|

|

Technical services

|

10% (43)

|

|

Other

|

8% (35)

|

Figure 2

Years of

experience.

Figure 3

Age ranges of

participants.

Figure 4

Gender identity

of participants.

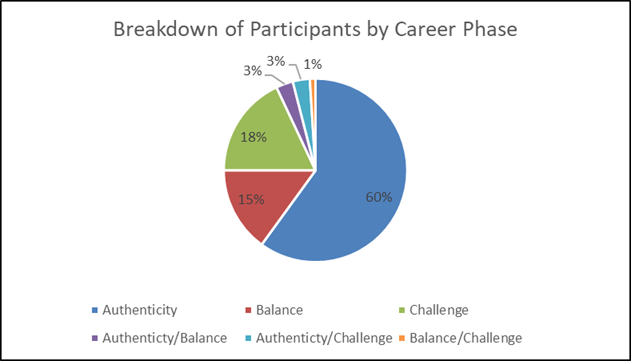

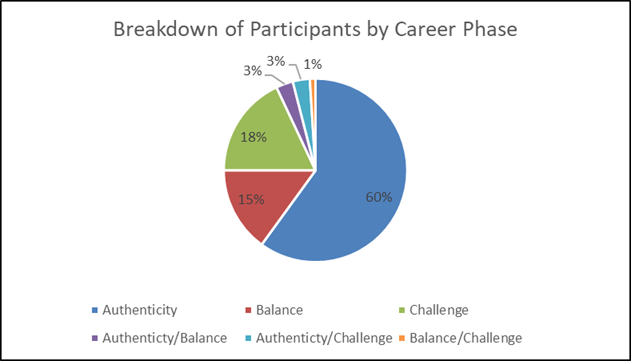

Focusing on the breakdown of participants in each

career phase (Figure 5), 60% of respondents identified as being in the

Authenticity phase, 15% in Challenge, and 18% in the Balance phase. Some

respondents identified as a combination of phases: 3% of all respondents

identified as Authenticity and Balance, 3% as Authenticity and Challenge, and

1% as Balance and Challenge. We have not focused on these results, as the small

percentages do not warrant generalizations and therefore do not factor into the

study’s overall findings.

Figure 5

Breakdown of

participants by career phase.

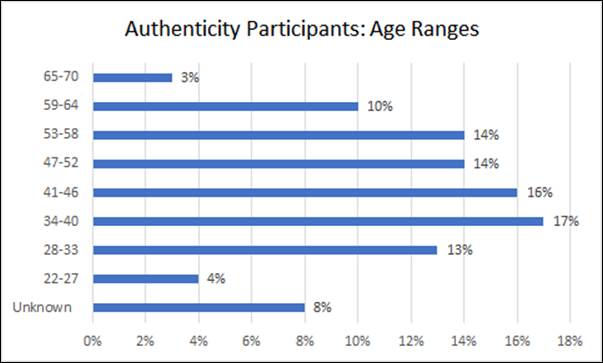

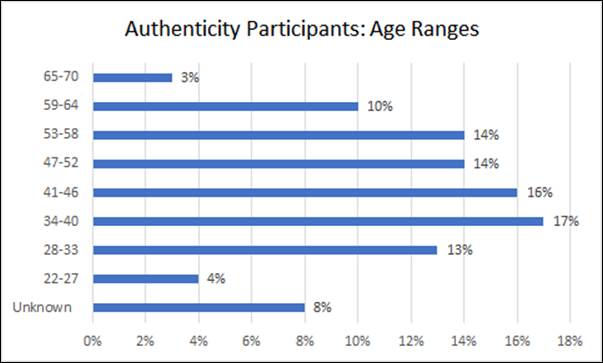

Among those in the Authenticity phase (Figure 6)

nearly one-fifth were entering mid-career and were between the ages of 34–40.

This age group was the largest in the survey population. A mere 3% of

participants were 65 years old or older. A similarly small percentage (4%) were

aged 22–27 and were at the beginning of their careers.

Figure 6

Age ranges of

Authenticity participants.

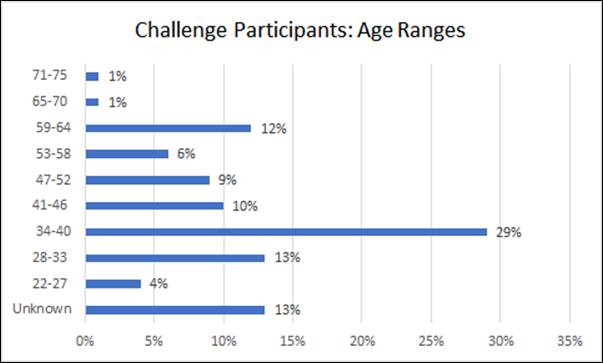

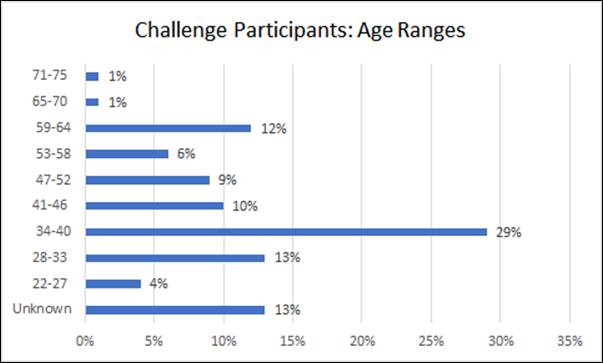

Nearly one-third

of participants in the Challenge phase (Figure 7) were between the ages of

34–40 and 12% were aged 59–64 or nearing retirement age. There were fewer

participants in the Challenge phase in what is traditionally thought of as

mid-career than in the Authenticity phase.

Figure 7

Age ranges of

Challenge participants.

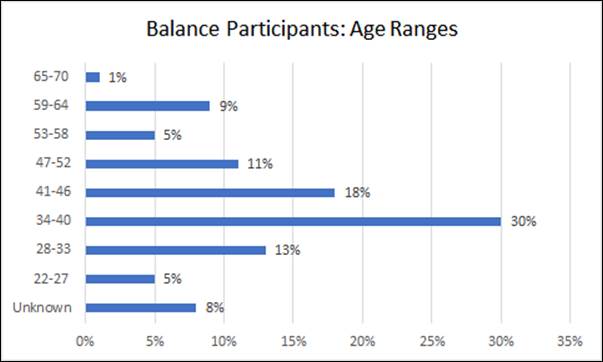

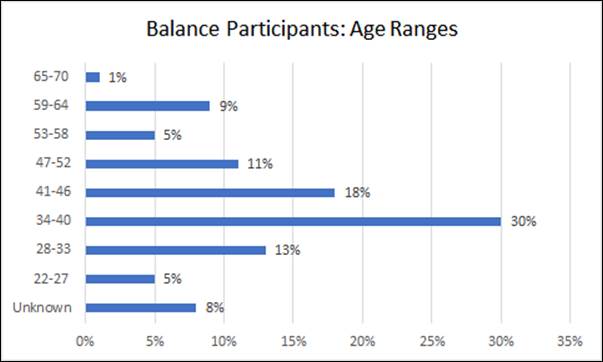

The largest

group (30%) who identified as in the Balance phase (Figure 8) were aged 34–40

years old. Similar to the age breakdowns of the other two phases, there were

few participants early in their careers or nearing retirement.

Figure 8

Age ranges of

Balance participants.

Sense of Administrative Support

Overall, most

participants expressed positive reactions when asked if they felt supported by

their administration. Drawing on participants’ comments to this question, they

define “supported” as having a supervisor who fosters accountability; displays

behavior to indicate they trust workers, including offering flexible schedules,

professional development, work–life balance, and autonomy to develop new

projects and structure work more generally; advocates for workers; fosters

creativity and collaboration; and engages with the work while not

micro-managing. The phrases participants used when they described not feeling

supported by their supervisors included not feeling respected, valued, or

understood; feeling there was incompetent leadership in the organization; and

not feeling connected to staff, patrons, or work culture.

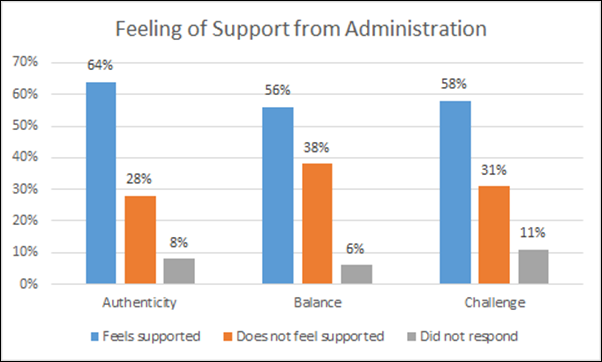

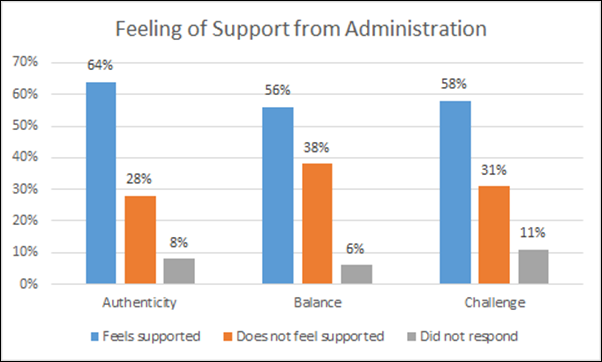

Figure 9

Feeling of

support from administration.

When asked if they felt supported (Figure 9), those in

the Authenticity phase reported the highest overall level of satisfaction,

followed by those in the Challenge and then Balance phases. Among the

participants who responded negatively, those in the Balance phase represented

the largest percentage of participants who did not feel supported by their

supervisor at 38%. Of the Authenticity phase, 28% responded negatively, and of

those in the Challenge phase 31% responded negatively.

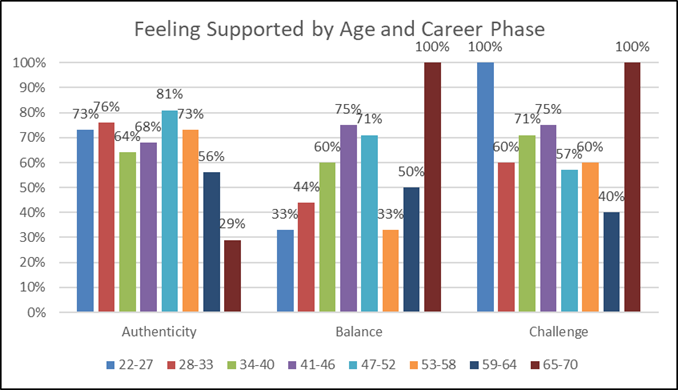

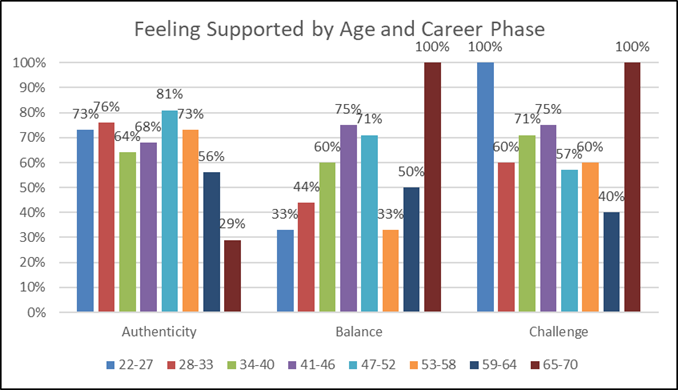

When considering the participants’ age together with

their career phase, those in the Authenticity phase experienced peak feelings

of support between the ages of 47–52 with 81% of respondents answering

positively (Figure 10). That percentage steadily declines amongst older

participants with only 29% of respondents ages 65–70 answering positively.

Those in the Balance phase experienced peak feelings of support between ages

65–70 at 100% followed by ages 41–46 with 75% of respondents answering

positively. The youngest (100% of those 22–27) and the oldest (100% of those

65–70) participants in the Challenge phase reported feeling supported. Unlike

the participants in the other two phases, those in the Challenge phase

experienced feeling lower levels of support between 47–52 and 59–64 years old,

with 57% and 40% respectively responding positively.

Figure 10

Feeling of

support by age and career phase.

Interest in Leadership and Supervisory Roles

Interest in serving in a management or leadership role

varied across age groups as well as career phases. When asking participants

about their interest, we defined management to mean a formal supervisory

position and leadership to be a little more ambiguous, including non-formal

roles such as project manager, mentor, or other influential role outside of

direct supervision.

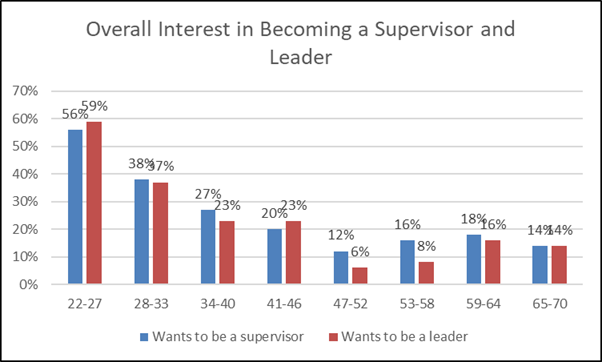

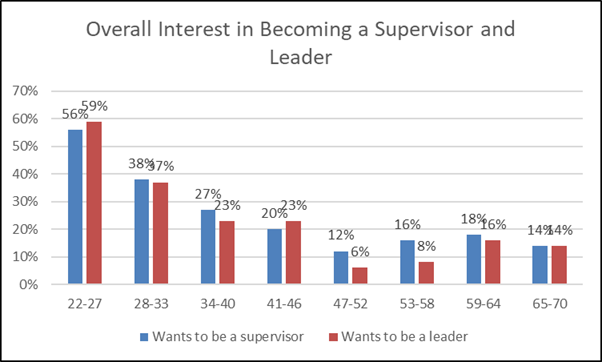

Figure 11

Overall interest in supervising or leading.

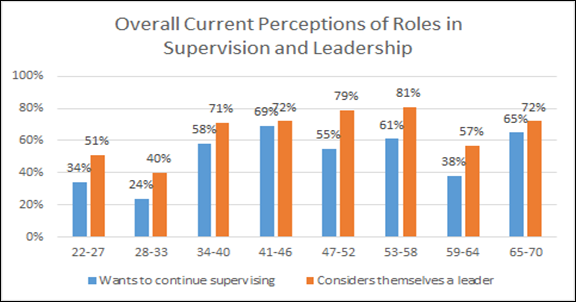

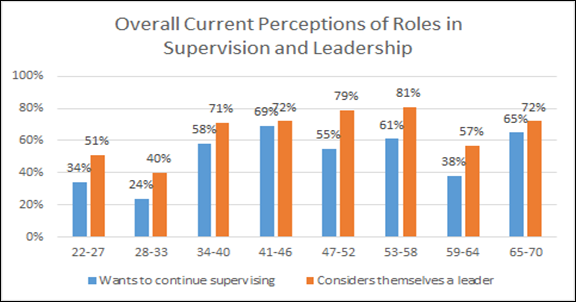

Looking at the overall picture, there was high

interest in becoming both a supervisor and an organizational leader from the

youngest cohort (Figure 11). However, interest diminished amongst the older age

cohorts, with the lowest interest showing in the 47–52 age group, before rising

slightly again.

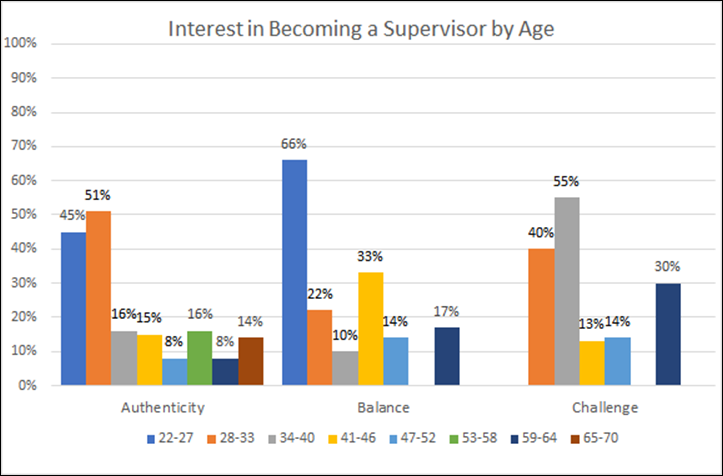

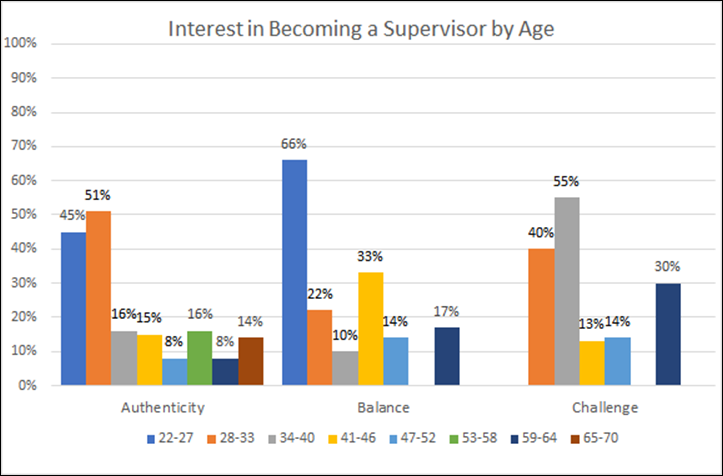

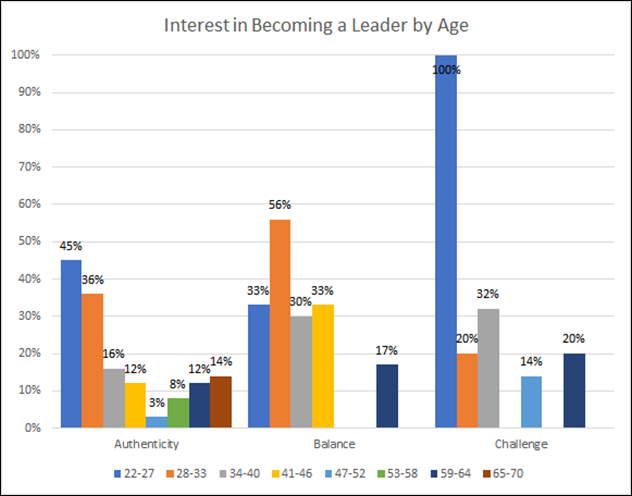

This can further be broken down by career phase, which

reveals more nuance about when interest peaks by age group (Figure 12). For

example, when asked their interest in becoming a supervisor, those between ages

28–33 were the peak age group in the Authenticity phase. For the Balance phase,

the peak occurred with librarians between ages 22–27 who are at the very

beginning of their careers. However, the peak was at a later age group, between

ages 34–40, for the respondents in the Challenge phase.

Figure 12

Interest in becoming a supervisor by age. (The gaps

between columns represent those age ranges with no participant responses.)

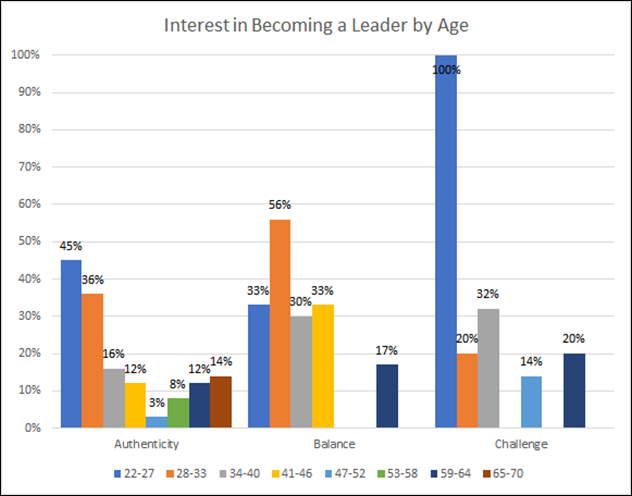

When

participants in the Authenticity phase were asked about their interest in becoming

a leader, those earlier in their careers responded more favorably than those

age 34 and older (Figure 13) Those who were early in their careers and in the Challenge phase expressed noticeable

interest in becoming leaders.

Interestingly, no participants aged 53–58 in the Balance and Challenges

phases answered this question. Interest in becoming an organizational leader

showed a noticeable drop in age groups older than 34 across all phases.

Figure 13

Interest in becoming a leader by age. (The gaps between

columns represent those age ranges with no participant responses.)

This sometimes reluctance in supervision and

leadership work can seem a stark contrast to the overall interest shown by

experienced librarians in either continuing in their role as a supervisor or in

their perception of themselves as organizational leaders (Figure 14). Younger

cohorts already working as supervisors or in leadership positions were less

enthusiastic about continuing, with the lowest numbers in the 28–33 range.

Figure 14

Overall current perceptions of supervision and

leadership.

The data reveals the intersections of age with career

phase, suggesting opportunities for administrators to nurture these

professionals and encourage them to continue in supervisory or leadership

roles.

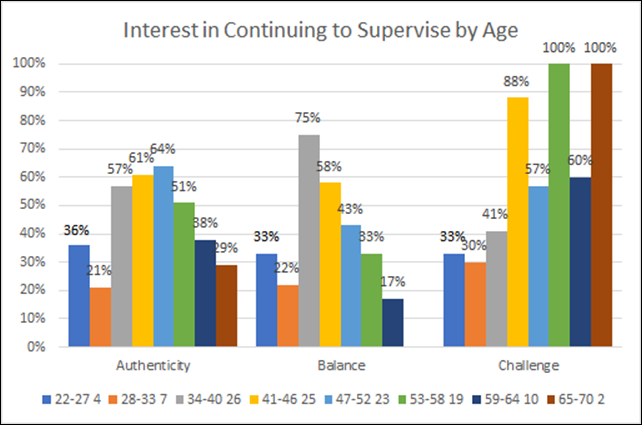

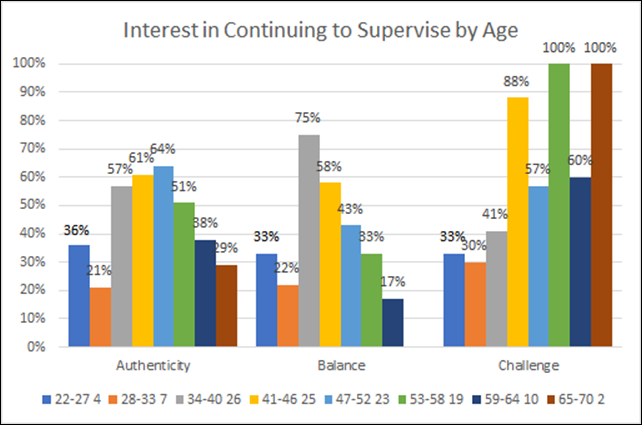

Common to each phase, practitioners seem interested in

continuing in a supervisory role when earlier on in their careers (Figure 15).

However, older cohorts in the Balance phase are less interested than those in

the other two phases in continuing to supervise. For those in the Authenticity

phase, interest peaked at mid-career between ages 47–52. For those in the

Challenge phase, interest was highest among the 41–46 cohort.

Figure 15

Interest in continuing to supervise by age. (The gaps

between columns represent those age ranges with no participant responses.)

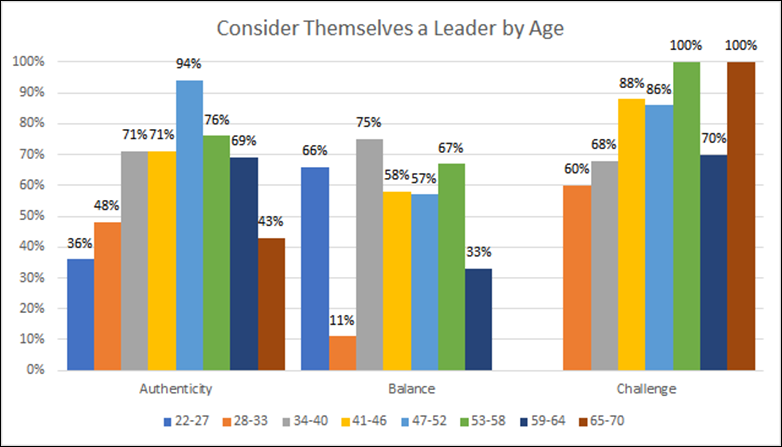

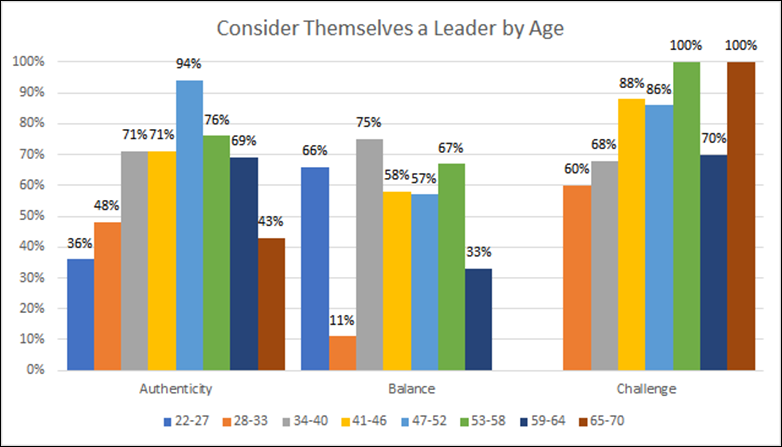

Those in the Authenticity phase identified most

strongly with being organizational leaders between the ages of 47–52 (Figure

16). Each cohort in the Challenge phase strongly identified as leaders, with

peak interest among those in mid-career and approaching retirement. Cohorts in

the Balance phase do not identify as consistently with being leaders, with

significant declines occurring among those ages 28–33, and again among the

59–64 years old.

Figure 16

Consider themselves a leader by age. (The gaps between

columns represent those age ranges with no participant responses.)

Discussion

Extrinsic and intrinsic motivations drive the

decisions and goals participants have made in their careers. When asked to

reflect on their perceptions about their career paths, and specifically to

consider the level of support they experienced and their interest in assuming

or continuing to serve in management or leadership roles, these sources of

motivations surfaced. Those in the Balance phase felt the least supported when

compared with those in the other two phases. When reflecting, one participant

commented “at my previous institution, my boss wanted us to take time for

ourselves, but he was also aggressive, critical, and unequal in his treatment.”

This group is managing extrinsic sources of motivation including care and life

responsibilities. That lack of support surfaced regardless of age, whereas in

the other two phases participants of different ages experienced varying levels

of support.

Those in the Authenticity phase responded more

positively to assuming leadership, as opposed to management, roles. One such

participant shared “I just took on new responsibilities and a new title (lateral

move) that is giving me the opportunity to add value to my organization.” This

finding speaks to the intrinsic motivation that participants expressed and

their interest in the non-hierarchical nature of such duties that do not

necessarily include supervisory responsibilities. Higher salary, an advanced

title, and the drive for greater responsibilities are the types of

intrinsically focused motivations that push those in the Challenge phase to

pursue and remain in management and leadership roles. As one participant

responded, “I came into librarianship as a second career after a divorce. My

motivation has primarily been focused on advancement . . . to provide for my

children. That being said, I also love a challenge, and leadership roles

provide those more than other positions.” Though this group certainly benefits

from being supported, they possess a strong drive to pursue advancement on

their own.

Support

The most consistent feelings of support across all age

groups, regardless of career phase, were expressed by those in the Authenticity

phase. One participant shared the following:

I am given

respectful space to share both my opinions and my ideas. When I provide enough

evidence of my position, I am generally permitted to move forward as I wish.

When I have not, I am respectfully challenged to collect more information and

strengthen my case. If an endeavor ultimately does not turn out to be

successful, I still feel respected for trying.

As someone who has strong personal values,

characteristic of the Authenticity phase, this participant appreciates being

given the opportunity to share their opinions and ideas. Working for someone

who then explains their decision helps the person to continue to feel respected

in the workplace. In contrast to those in the Challenge phase, those in the

Authenticity phase felt the least supported at the ages of 34–46 years old. As

one participant in this cohort explained,

I am in the

middle of changing careers and want to be more involved in Heritage

Preservation, especially international, intangible and theoretical. So I am back in school myself. I feel that archivy [sic] is a calling, that it called me and for the

last 20 years I have served, but I am burnt out and tired of the same old

battles. Also, this field does not pay well enough.

Mid-career practitioners, who identify as in the

Authenticity phase have tried to fit themselves into the values mold of their

organization and have not found a good fit. Participants entering mid-career

seem to experience a crossroads where they confront their own values and those

of their organization. As a result, practitioners appear more inclined to make

a career pivot that more closely aligns with their personal values.

The highest percentage of respondents who did not feel

supported were those in the Balance phase. Mainiero

and Sullivan (2006a) point to support and flexibility as key drivers for women

making career decisions. Such support to juggle work and life responsibilities

can come from their spouses or partners, employers, or family members. The

responses from this study’s participants echo Mainiero

and Sullivan’s (2006a) conclusion that the absence of such support in women’s

quest for balance strongly impacts their career decisions (p. 193). Such

responses suggest that supervisors have not found or implemented adequate

strategies to best meet the needs of those who balance family, relationships,

caregiving, and personal health and emotional conditions throughout the

lifecycle. One participant reflected on the supportive relationship they have

with their supervisor:

My current

supervisor is also a mother and is very supportive of taking time off to attend

kid things, staying home with sick kid, etc. I feel that the administration at

my current job are very understanding and supportive of work-life balance. I

also have been supported in professional development and I know that my

supervisor wants me to succeed in my career.

Older participants reported an absence of support,

suggesting that supervisors may not give as much attention to work–life balance

issues throughout the lifecycle. As one participant explained, “I feel that I

am on the B team and that the newer librarians have been given the support to

shine.” When analyzing these results by age, it is worth noting that only one

participant was in the 65–70 age group, so additional data would be needed to

determine if those in the Balance phase feel supported later in life.

The data indicates that for those aged 34–46 in the

Challenge phase, practitioners begin to take on advanced roles or move into

management positions as they feel a strong sense of support from their

supervisors. One participant responded “I have the resources I need and am

encouraged to pursue my own interests and professional contributions.”

Intrinsically motivated, this participant’s comment highlights the individualistic

nature, rather than values-driven or work–life balance focus, of those in the

Challenge phase. By contract, practitioners approaching retirement feel waning

support. Participants aged 47–52 experienced a lower level of support with 57%

responding positively, while only 40% of those aged 59–64 felt supported. This

finding suggests that once practitioners have less that challenges them

professionally, they feel less supported to pursue their goals.

Interest in Leadership and Supervisory Roles

Participants who identified themselves as being in the

Authenticity phase seemed much more interested in leading informally rather

than advancing through formal management structures. One participant reflected:

“I am currently in middle management and find the work challenging and

fulfilling. I'm not sure I want to go further up the ladder because it might

mean having to make decisions that are inconsistent with my values.” Those in

the Authenticity phase are also strongly interested in their lives outside of

work and a focus for them is work–life balance. Participants’ interest in being

a supervisor peaked at the 28–33 age range, which suggests the beginning of a

values misalignment with their organization or profession. The issue of

competing priorities and misaligned values led one participant to share that

these struggles are “at the root of the burnout issue, especially for women who

find it difficult to be managers at work and caretakers at home . . . many of

us do not feel listened to or respected in dysfunctional academic libraries.”

These early experiences and misalignment with their personal values lead

practitioners to pull back from formal supervisory roles and seek out

alternative career paths. Practitioners seemed to shift and more strongly identify

themselves as organizational leaders at the 34–40 age range. One participant

stated:

I prefer to lead

in less formal ways like chairing campus committees or being part of task

forces or working groups. I find it more satisfying to work on a project and

see it completed or implemented rather than having to deal with ongoing issues

with no end in sight.

Overall, these participants expressed more sources of

extrinsic motivation, such as finding fulfillment through making a difference

in students’ lives, rather than sources of intrinsic motivation, such as

building a career through promotions. An informal role could position those in

the Authenticity phase to become strong leaders of project-based work with

concrete objectives and timelines; thereby enabling these practitioners who are

values-oriented to feel a sense of accomplishment, which can be harder to

attain when in a formal supervisory role.

This source of motivation contrasts quite noticeably

with participants who identified as being in the Challenge phase. Participants

expressed interest in new positions, the opportunity to supervise and earn

promotions and increased salaries. One participant stated their goal as:

Yes, I would

like to become more of an organizational leader, but not at my current place of

employment. I would like to work at an organization where I felt there were

more opportunities for the kind of work I enjoy doing, so that there would be

clearer lines towards leadership opportunities.

This participant identified their career goal and

sought to advance by leaving the organization and working in a library with an

organizational culture oriented toward leadership opportunities. Those in the

Challenge phase aged 28–33 responded positively with 60%, considering

themselves to be organizational leaders earlier in their careers. Of the three

groups, this group showed the highest satisfaction at being a supervisor later

in their career.

Finally, those in the Balance phase most strongly

indicated that they do not feel prepared for management positions. Rather than

seek out leadership or supervisory responsibilities, those in the Balance phase

may find themselves asked to assume those roles before they have gotten the

training or identified an advancement path as a career goal. One participant

stated, “I became a leader somewhat unwillingly and in a time of need for our

library. I often feel inadequate and unprepared in my work.” This participant’s

experience underscores the impact of being extrinsically motivated. Overall,

those in the Balance phase do not show a strong propensity for wanting to be

supervisors, especially early in their careers. One participant commented: “I

think the profession as a whole needs to reconcile how

librarians can translate their skills across positions/organizations/etc. I

have no idea how to leverage the experience I have to transition to a different

type of library work.” Such practitioners can feel stalled as they may be organizational

leaders, but not supervisors, due to the limitations of the library’s

hierarchy. Taking a more a passive approach to their careers highlights the

importance of training and organizational support for those prioritizing

work–life balance.

Looking across the career phases amongst those who are

not already supervising, the strongest interest (58% of respondents) in

assuming such a role came from the youngest cohort, who are the newest to the

profession and most enthusiastic to take on the roles. But for those aged 34–40

that interest dropped to below 30% with subsequent age cohorts even less

interested in assuming management roles. The surprisingly low interest in

continuing to supervise amongst those in their late twenties and early thirties

is also concerning. Why don’t these young professionals want to keep

supervising? One participant commented: “Right now, I'm feeling very drained

from having no support from my supervisor + having direct reports that clearly

don't care for my supervisory role . . . external factors like low morale and

lack of institutional support are affecting my views and values . . ..” Their

younger counterparts expressed strong interest in supervising, and yet this

group of similarly aged individuals seemed uninterested in continuing to

supervise. Not getting enough training or support could be an indicator. The

responsibilities of the position may compete too strongly with raising a family

or participating in outside activities. The interest in continuing to supervise

noticeably rises in the next age cohort (34–40), suggesting the impact of a

degree of maturity, increased wisdom, and comfort due to job experience.

Additional research is needed to determine the root causes of this uninterest

in the younger group.

Leadership perception and interest from participants

followed a similar pattern. One participant stated, “I am very interested in

what library leadership looks like outside of the traditional management role

or model. There are many, many ways to exercise leadership skills that do not

involve becoming a direct supervisor or manager.” The 28–33 age group was least

likely to consider themselves current leaders; this group also displayed the

lowest interest in being a supervisor and seems to be struggling with issues related

to both formal and informal leadership, in ways that the age cohorts that are a

little younger and older, do not. One participant who identified as in the

Authenticity phase commented:

While I have had

a few promotions earlier on in my career, I feel like I have more or less

plateaued. I am not really seeking new opportunities or challenges because I

don't feel that I can take much more on at this point in my life.

This sentiment exactly matches the results from the

supervision question, suggesting, perhaps unsurprisingly, that older librarians

are less interested in being leaders. Experiencing burnout may be one cause. As

one participant reflected, “I get tired and need more vacation and down time

[than] in the past. At times I feel burned out with the long hours and social

events required of my position.” It is notable that interest in continuing to

supervise peaked among the mid-career group of 41–46, which suggests career

burnout could be more likely to occur during this age range. Each subsequent

cohort also showed a 20% difference between interest in being a leader vs.

interest in being a supervisor.

Limitations

The gender breakdown of participants is the principal

limitation of this study; 74% of the sample identified as female. Therefore,

the analysis and recommendations presented here may not be generalizable to

those practitioners who identify as male or gender variant/non-conforming. The

authors also acknowledge that they did not collect data on race, ethnicity,

sexual orientation, disabilities, or other identity-related categorizations

that could have provided further data on the social hierarchies inherent in

libraries. Further research is suggested on identifying library career

motivation issues from an intersectional perspective.

Recommendations

When considering how administrators and supervisors

can best foster leaders and managers and support their work forces overall,

this research yields several key contributions to the literature.

Administrators should seek out information about employees’ career phases as

part of onboarding by implementing specific strategies. Such strategies could

help to identify sources of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, career goals,

personal values, and non-work-related interests and responsibilities. Employers

can then be better positioned to support their staff as they develop.

When working with librarians who identify with the

Authenticity phase, administrators should work with their employees to develop

career goals that are extrinsically based, such as what can be achieved through

good work rather than striving for a dream position. Administrators should

provide these librarians with the latitude to better align their job with work

goals, such as giving someone who loves to teach the chance to teach more or

take a leadership role in developing an instruction program. These librarians

embrace opportunities to lead via projects, committees, and other

non-hierarchical leadership work. Administrators should proactively engage

those librarians in the Authenticity phase aged 34–46 in discussions of

organizational values and priorities, which may help librarians to feel better

aligned with their organizations. Due to the high value those in the

Authenticity phase place on principles, administrators should include them,

when possible, in institutional and departmental visioning and goal setting and

allow them to align their work to the bigger picture. The majority of survey

respondents (60%) identified with the Authenticity phase; if this figure is

consistent with the general library population, then library administrators

would do well to offer numerous informal leadership opportunities and provide

inclusive ways for librarians to influence the work culture.

Librarians in the Balance phase would benefit from

early opportunities to develop leadership roles or serve in supervisory roles.

These early opportunities better fit with their efforts to prioritize

non-work-related responsibilities later in life. Training must precede such

opportunities to best support and encourage skill development. They should

encourage their staff to seek out mentors as they consider potential new roles.

Administrators should also provide more hands-on support through conversation,

feedback, and opportunities for stretch assignments.

For those who identify with the Challenge phase,

administrators should work with them to find early opportunities to fill a

leadership role or supervise others. Organizations should implement formal

promotion guidelines, which will benefit all employees, and keep this group

engaged. Librarians in the Challenge phase are intrinsically motivated to

achieve and strive. They may experience disappointment as newer career

librarians continue to advance while they begin to plateau later in life.

Regardless of age, these librarians continue to crave the latitude to redefine

their position or take on new responsibilities to alleviate potential boredom.

Whichever career phase a librarian identifies with,

administrators should strive to nurture and support young supervising

librarians in order to foster better managers and leaders and sustain their

interest in the role. Such strategies could include offering flexible

scheduling to accommodate care duties, options to work part of their time

remotely, or adjusting job duties as care duties demand. Feeling as though the

administration has their backs was the most common response from participants.

As one participant shared, “my immediate supervisor . . . [is] very attentive

and points out when I'm working towards burnout. The[y] remind me to try to

balance everything.” Librarians working in an organization that demonstrates it

supports all of its employees will be more engaged and motivated. When

considering strategies to maintain current levels of support or to address gaps,

administrators should certainly get to know their employees to find out what

kind of support would best work for them and what future roles and

responsibilities best fit with their aspirations.

At their core, the recommendations described here are

intended to develop and maintain a highly engaged workforce. Clear

communication, transparency, and creative problem solving will be key to

implementing these recommendations. Organizational culture heavily impacts

personal behavior and a leader’s ability to bring about change (Mainiero & Sullivan, 2006a, p. 243). At a fundamental

level, such leaders must consider the kinds of changes their organization can

withstand as they strive to best support and foster the growth and development

of all of their employees.

Conclusion

The findings from this study underscore the importance

of providing academic librarians flexibility and support as practitioners seek

to craft their own career paths. Such paths may include advancing into senior

leadership positions and back out again, being fulfilled in a non-managerial

position that gives practitioners time to spend on care responsibilities, or

being in roles that align with their personal values and ethics. Not mutually

exclusive, this study illustrates how career paths intersect with life events,

goals, and experiences. Practitioners shift between those Challenge, Balance,

and Authenticity phases as their needs evolve over the course of their careers.

Each phase provides leaders with its own framework through which to communicate

with their employees and best meet them where they are, in terms of their

priorities and what they value or need at that particular time.

Leaders can no longer afford to be complacent when it

comes to talent development and retention. As this study highlights,

practitioners are looking for more than just a paycheck in recognition of their

time and contributions. Rather, leaders should consider the intrinsic and

extrinsic motivations that guide each of their staff members to provide

opportunities that fit with the employees’ career phases and senses of

themselves within that phase. These phases provide organizations with a new

framework to imagine structuring work, roles, and support within libraries and

to allow academic librarians a lens for viewing their careers that replaces the

straight linear progression of the past. Academic library leaders must

recognize the changing needs of their workforce and strive to evolve their

practices, policies, and cultures to best support their teams.

Author Contributions

Lori Birrell: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation,

Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing –

original draft, Writing – review & editing Marcy A. Strong: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation,

Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft,

Writing – review & editing

References

Adigwe, I., & Oriola, J. (2015). Towards an understanding of job

satisfaction as it correlates with organizational change among personnel in

computer-based special libraries in Southwest Nigeria. The Electronic

Library, 33(4), 773–794. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-01-2014-0018

Barclay, S. R., Stoltz, K. B., & Chung, Y. B. (September 2011).

Voluntary midlife career change: Integrating the transtheoretical model and the

life-span, life-space approach. Career Development Quarterly, 39,

386–399. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.2011.tb00966.x

Betz, N., & E. (2003). A proactive approach to mid-career

development. The Counseling Psychologist, 31(2), 205–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000002250478

Farrell, M. (2013). Lifecycle of library leadership. Journal of

Library Administration, 53, 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2013.865390

Fink, A. (2013). How to conduct surveys: A step-by-step guide (5th

edition). Sage.

Franks, T. P. (2017). Should I

stay or should I go? A survey of career path movement within academic, public

and special librarianship. Journal of Library Administration, 57(3),

282–310, https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2016.1259200

Fyn, A., Heady, C., Foster-Kaufman, A., & Hosier, A. (2019). Why we

leave: Exploring academic librarian turnover and retention strategies. Association

of College and Research Libraries Conference Proceedings http://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/conferences/confsandpreconfs/2019/WhyWeLeave.pdf

Lacey, S., & Stewart, M. P. (2017). Jumping into the deep: Imposter

syndrome, defining success, and the new librarian. Partnership: The Canadian

Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 12(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v12i1.3979

Lyons, S. T., Schweitzer, L., & Ng, E. S.W. (2015). How have careers

changed? An investigation of changing career patterns across four generations. Journal

of Managerial Psychology, 30(1), 8–21. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1108/JMP-07-2014-0210

Mainiero, L. A., &

Sullivan, S. (2006a). The opt-out revolt: Why people are leaving companies

to create Kaleidoscope careers. Davis-Black Publishing.

Mainiero, L. A., &

Sullivan, S. (2006b). The Kaleidoscope Career Self-Assessment Inventory: A

guide to understanding the career parameters that drive your motivation for work.

Unpublished manuscript.

Mallaiah, T. Y., & Yadapadithaya, P. S. (2009). Intrinsic motivation of

librarians in university libraries in Karnataka. DESIDOC Journal of Library

& Information Technology, 29(3), 36–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.14429/djlit.29.250

Montgomery, D. L. (2002). Happily ever after:

Plateauing as a means for long-term career satisfaction. Library Trends, 50(4),

702–716.

Morris, S. (2019). ARL Annual Salary Survey 2018–2019.

Association of Research Libraries.

O’Neill, M. S., & Jepsen, D. (2017). Women’s desire for the

kaleidoscope of authenticity, balance, and challenge: A multi-method study of

female health workers’ careers. Gender, Work, and Organization, 26(7),

962–982. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12317

Pennell, K. (2010). The role of flexible job descriptions in success

management. Library Management, 31(4/5), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1108/01435121011046344

Power, S. J., & Rothausen, T. J. (2003).

The work-oriented mid-career development model: An extension of Super’s

maintenance stage. The Counseling Psychologist, 31(2), 157–197. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0011000002250479

Ridley, M. (2014). Returning to the ranks: Towards an

holistic career path in academic librarianship. Partnership: The Canadian

Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 9(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v9i2.3060

Sullivan, S., & Mainiero, L. A. (2008).

Using the Kaleidoscope Career Model to understand the changing patterns of

women’s careers: Designing HRD programs that attract and retain women. Advances

in Developing Human Resources, 10(1), 32–49. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1523422307310110

Sullivan, S. E., Forret, M. L., Carraher, S. M., & Mainiero,

L. A. (2009). Using the Kaleidoscope Career Model to examine generational

differences in work attitudes. Career Development International, 14(3),

284-302. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430910966442

Appendix

Survey

Instrument

The Kaleidoscope

Career Model (Mainiero, et al), uses three phases:

challenge, authenticity, and balance, as a non-linear approach to understanding

the mapping of career trajectories, agency and decision-making power to the

individual, rather than the organization, based on the person’s own values and

choices. Applying this model in the academic librarian context, we seek to

better understand where those pivot points exist for professionals, and more

broadly how these perceptions impact their sense of satisfaction with their

career trajectories, and sense of support they receive from their employers.

This survey

contains questions about your experiences and/or feelings concerning how you

conceive of and perceive of your career path.

We would like

you to complete the whole survey, but you may skip any questions that you don’t

feel comfortable answering or can discontinue your participation at any time.

The survey data results will be kept for analysis purposes only and will not be

released in any publication or report; they will be destroyed once the analysis

is complete. Only the investigators will have access to your individual

responses. All the information received from you will be strictly confidential

and will be stored on a password protected local (non-networked) hard drive.

You will not be identified nor will any information that would make it possible

for anyone to identify you be used in any presentation or written reports

concerning this project. Only summarized data will be presented in any oral or

written reports.

Your

participation in this project is completely voluntary. You are free not to

participate or to withdraw at any time, for whatever reason, without risk. No

matter what decision you make, there will be no penalty or impact to your

employment. The Institutional Review Boards of the University of Arkansas and

the University of Rochester approved this study. Your participation in this

survey indicates your consent to these terms.

For

more information about this project you should contact: Lori Birrell by phone at 479-575- 8443, or by email at:

lori@birrell.us or Marcy Strong by phone at 585-273-2325, or by email at

strongstuff@gmail.com.

By

clicking on the red arrow below, you are agreeing to participate in this

survey.

[The

Kaleidoscope Career Model statements and answer scales have been redacted for

publication.]

In

what ways, if any, do the characteristics of the phase you scored the highest

in describe your current thinking about your career path? (open ended)

In

what ways, if any, do the characteristics of the phase you scored the highest

in NOT describe your current thinking about your career path? (open ended)

Do you feel supported by your library administration?

Please enter any details you'd like to share in the text box next to your

response.

Yes _______________________________________

No ________________________________________

Are you

currently a supervisor (defined as managing faculty, staff, students, interns,

or volunteers)?

Yes No

If yes, would

you like to continue to be a supervisor in the future?

Yes No

If no, would you

enjoy the opportunity to become a supervisor in the future?

Yes No

Do you consider

yourself to be a leader in your organization? (Defined here as someone who:

does project management tasks, large-scale decision making, coaching/mentoring

of others).

Yes No

If no, would you

enjoy the opportunity to become an organizational leader in the future?

Yes No

Do you have any

other thoughts about your career path, the self-inventory tool and Kaleidoscope

Model, or this topic more generally that you’d like to share? (open ended)

The following

are demographic questions: What kind of library do you currently work in?

- 4 year, doctoral degree granting university or college

- 4 year, masters degree granting university or college

- 4 year, bachelor

degree granting university or college

- 2 year, community

or vocational school

- Other (please describe below)

What area of

librarianship do you currently work in? (For this question, we’re asking about

your primary job duty. Department heads, please indicate the functional area

you work in)

- Administration

- IT

- Public Services

- Technical Services

- Special collections/archives

- Other (Please enter your area of librarianship in the text box.)

How many years

have you worked in the library science profession?

- Less than 2 years

- 2-5 years

- 6-10 years

- 11-15 years

- 16-20 years

- 25+ years

Please select

your age range.

- 22-27

- 28-33

- 34-40

- 41-46

- 47-52

- 53-58

- 59-64

- 65-70

- 71-75

- 75+

Please identify

your gender.

- Male

- Female

- Gender Variant/Non-Conforming

- Other

- Prefer not to answer

![]() Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice

Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice![]() 2022 Birrell and Strong. This is an Open Access article distributed under

the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2022 Birrell and Strong. This is an Open Access article distributed under

the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.