Research Article

If You Build it, Will They

(Really) Come? Student Perceptions of Proximity and Other Factors Affecting Use

of an Academic Library Curriculum Collection

Madelaine Vanderwerff

Librarian, Assistant

Professor

Mount Royal University

Library

Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Email: mvanderwerff@mtroyal.ca

Pearl Herscovitch

Librarian, Associate

Professor

Mount Royal University

Library

Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Email: pherscovitch@mtroyal.ca

Received: 5 Nov. 2020 Accepted: 2 Apr. 2021

![]() 2021 Vanderwerff and Herscovitch. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2021 Vanderwerff and Herscovitch. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29875

Abstract

Objective – This study investigated student perceptions of an undergraduate

university library’s curriculum collection, before and after a move to a new

library building. The objective was to identify how factors such as proximity

to program classrooms and faculty offices, flexible seating, accessibility, and

other physical improvements to the space housing the collection impacted

students’ perceptions.

Methods – This

longitudinal study conducted between 2016 and 2017 used a combination of

methods to examine whether library use of a specialized academic library

collection was impacted by a significant space improvement and change in

location. A cohort of education students was surveyed before and after the

construction of a new building that housed both the library and their

department and co-located the curriculum collection with departmental teaching

spaces. The students were surveyed about their use of the space and resources.

The researchers then compared the survey results to circulation data. The

researchers ground this study in Lefebvre’s spatial triad theory, applying it

to library design and collection use (Lefebvre, 1992).

Results –

Researchers identified proximity to classrooms and general convenience as the

dominant factors influencing students’ use of the collection. Survey results

showed an increased awareness of the collection and an increase in use of the

collection for completion of assignments and practicum work. Circulation data

confirmed that between 2016-2019, there was a steady increase in use of the

curriculum collection.

Conclusion – Students’ responses revealed that physical characteristics of the

space were less important than proximity, the major factor that impacted their

use of the curriculum collection. This revelation confirms Lefebvre’s idea that

spatial practice, i.e., how users access and use the space, is more significant

and identifiable to students than the design and physical characteristics of

the space.

Background

In 2009 Mount Royal University (MRU) transitioned from

a college to a university, and in 2011, a university transfer program in

education became a full Bachelor of Education degree. Based on a recommendation

by the provincial approval body, Campus Alberta Quality Council (CAQC), the

education librarian was granted one-time funds to transform the collection,

which had focused on pedagogical theory and children’s literature, to support

students in their academic work and their practicum placements in K-7 settings.

This transformation required the acquisition of physical objects such as kits,

realia, games, manipulatives, puppets, musical instruments, teacher support

material, and textbooks. Special funding for the

collection was expended by 2014. After 2014, the curriculum collection was

supported through an annual collection budget allocation.

The provincial

government committed funding to support the building of the Riddell Library and

Learning Centre (RLLC), a free-standing, four-story facility, which opened in

2017. Features of the RLLC include: data and touch-screen

visualization spaces, a makerspace, a 360-degree immersive studio, an XR

experience lab, 2 flexible teaching classrooms that can accommodate up to 70

students, a temperature-controlled archive, audio-productions suites, 31

bookable group rooms outfitted with screens and white boards, 2 presentation

practice rooms, silent study areas, computer commons, and group study areas,

and more. The building is also home to the Academic Development Centre, the

Institute for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, Student Learning

Services (Mount Royal University’s student writing centre) and the Department

of Education. The curriculum collection was relocated from its dusty, dark

corner in the old library to a bright space with flexible furniture and

shelving that is both adaptable and appropriate. The collection is adjacent to

the Department of Education where Bachelor of Education students attend classes

in the majority of their core courses, and is now essentially embedded in the

department.

In anticipation of the move, the authors were

interested in examining whether improved library facilities would have an

impact on the use of the curriculum collection. We supposed that the curriculum

collection was not well-used in the old library because of the unfavourable

location and predicted that an improved environment would have a positive

impact on use. The collection was in a remote corner that had very poor

lighting and on shelving that could barely accommodate the oversized materials

and larger kits. The space did not provide students or other potential users

with an inviting place to explore the collection. We were interested in

investigating what effect co-location or proximity to classrooms might have on

students’ use of the collection.

Terms used:

Use: Use has been defined in many ways in library

literature. Fleming-May (2011) identified multiple applications of the word

“use” through content analysis, which could include an interaction with all library

resources (things, people, services, space) measured by door counts, occupation

of physical space, bibliographic analysis measuring instances in which library

resources are applied or referred to as an abstract concept such as process, or

utility. In the context of this study, use is defined as access to items in a

physical collection. Use refers to transactional instances in which individuals

check physical items out of the library or interact with physical collection

items.

Co-location: Researchers applied the definition provided by Bodolay et. al (2016) as a location convenient to users

across separate campus units. This does not imply the creation of new services

that leverage the joint expertise of the library and campus partners.

Curriculum collection:

ACRL’s Curriculum Materials Committee has developed

Guidelines for Curriculum Materials that define Curriculum Collections as

physical locations for instructional resources for preschool through grade 12

students. Materials are used by education students and faculty to develop

curricula and lesson plans and to complete course assignments. These

collections or branch libraries are often referred to as a Curriculum Materials

Center or Instruction Materials Lab. Curriculum collections may be housed in a

main campus library or the building housing the Faculty or Department of

Education program. (Curriculum Materials Committee, Education and Behavioral

Sciences Section, ACRL, 2017)

The Literature

Facility Improvement and Impacts on Library Use

Libraries completing facility improvements have

reported an increase in use of library space and library collections

post-renovation (Albanese, 2003; Martell, 2008; Shill &Tonner, 2004).

Certain factors impacting use of facilities or collections in academic

libraries have been identified in the literature over the past 20 years. These

include amount of space, noise level, crowdedness, comfort, type and

flexibility of furniture, cleanliness, access to services and technology, and

availability of collaborative space (Bailin, 2013;

Cha and Kim, 2015; Gardner & Eng, 2005; Given

& Leckie, 2003; Holder & Lange, 2014).

Proximity to collections also affects how students make choices in the

selection of information to support their assignments and coursework as well as

where they physically choose to sit in the library (Julien & Michels, 2004; May & Swabey,

2015). McCreadie and Rice’s (1999) examination of how

and why users access information included physical constraints such as

geography, space, distance, and proximity. Time factors, convenience, and ease

of use have been identified as significant considerations in the context of

information seeking behaviour (Connaway, Dickey &

Radford, 2011; Savolainen, 2006). Literature on the importance of a

student-centred approach to library access suggests that library co-location

with a student’s home department contributes to the development of a more

student-focused environment, increasing access to both services and

discipline-specific resources (Defrain & Hong,

2020).

Convenience and Proximity

The theoretical grounding for this study was based on

Henri Lefebvre’s spatial triad theory applied to library design and subsequent

user perception and use. Lefebvre was a Marxist philosopher, well known for his

work on spatial theories. In Lefebvre’s view, space “cannot be separated from

social relations and is the product of ideological, economic, and political

forces (the domain of power) that seek to delimit, regulate, and control the

activities that occur within and through it” (Zieleniec,

2013, para. 9). The spatial triad theory is introduced in Lefebvre’s, The production of space (La production de

l’espace) (Lefebvre, 1992). This is a complex theory

that has the potential for wider application in the study of library spaces as

it seeks to “uncover the social relations involved in the production of space

and the significance this has for a comprehensive knowledge of space” (Zieleniec, 2007, p. 70).

The relevance to libraries becomes apparent in

Lefebvre’s work when we consider the importance of social relationships in the

production of space—space

transformed to place as it is imbued with significance and meaning assigned by

the everyday practice of its users (Zieleniec, 2007).

The three elements of the triad are:

●

representations

of space (conceived space) interpreted as the actual characteristics of library

space as developed by architects, planners, and engineers,

●

spatial

practices (perceived space) interpreted as the user’s perception of the built

space,

●

representational

spaces (lived space) interpreted as library users’ access and use of the space

(Ilako et al., 2020; Leckie & Given, 2010).

In Lefebvre’s view, “spaces become places when

individuals and groups assign meaning and social significance to them”. Without

meaning, space remains and exists in the realm of the abstract, defined by

architects and planners (Zieleniec, 2013, p. 953).

Our application of Lefebvre’s spatial triad theory aligns with McCreadie and Rice’s (1999) description of constraints,

such as geography, demographics, environmental arrangement, space, distance,

and proximity which can lead to perceived availability or convenience. The

physical attributes of a library space can serve to influence or constrain

access to information along dimensions of distance and proximity, openness and

security, and clarity or obstruction. This investigation provides an

opportunity to explore how user experience impacts use of or access to a

discipline specific collection. Applying Lefebvre’s theory allows for a better

understanding of the meaning and significance users assign to this area of the

library as it transitions from space to place. An understanding of students’

perception of the space, and their everyday practice within it, will help the

authors identify elements of control and regulation that may hinder or

contribute to how students might assign significance to the space.

Savolainen’s (2006) work aligns with McCreadie and Rice (1999), reinforcing the importance of

space and time on the use of information and spatial factors related to

physical distance between the information seeker and information sources.

Savolainen’s idea that distance and time factors serve as a context that

informs choice about information seeking is detailed by Connaway

et al. (2011), who view convenience as a situational criterion in people’s

actions, and together with ease of use, as determining factors in how

individuals make their information seeking decisions.

Feedback gathered through student consultations on

library redesign often reflects a preference for discipline specific libraries

near their department (McCullough & Calzonetti,

2017; Teel, 2013). Students may protest or organize petitions as they did in

response to a proposed STEM branch library consolidation at University of Akron

(McCullough & Calzonetti, 2017). MRU Library’s

curriculum collection is primarily a physical collection, consisting of print

materials, manipulatives, juvenile literature, kits, and models that users need

to physically access. Guidelines for Curriculum Materials Centres (2017),

developed by an ad hoc committee of ACRL, suggest that these libraries are

often located in the same building as the Department of Education. This

preference for a library’s proximity to a department is reinforced in an article

reviewing curriculum collections in Australian universities, where a change in

use patterns was identified when curriculum collections moved from the building

housing the education department to the main library:

...moving into the library often changed the focus of

collection use,

from being an active teaching and learning area that

replicated classroom and

school library spaces, to being simply another library

collection distant from

the students’ learning environments. Hence, the

collections were not used as

much or in the same way. For example, academics did

not bring groups into the

collection as much as they had previously, when the

collection may have been adjacent

to their lecture rooms. Nor did students use the

collections located in the library in the

same way (Locke, 2007, p.4).

In a study by Teel (2013), student consultations

revealed the need for improvement in physical space and technology in their

curriculum materials centre and importantly, a preference for the centre to

relocate to the Faculty of Education building. A more recent study by Stoddart

and Godfrey (2020) examined space usage in a newly renovated curriculum centre

housed in the education building. They identify the most frequently used spaces

in order to better understand the centre’s contribution to “campus learning”,

and emphasize the importance of connecting library design to program and

university learning outcomes. These authors refer to Van Note Chism’s

discussion of the creation of spaces that have been intentionally designed to

impact student learning. Many of the elements described by Van Note Chism were

considered in the design of MRU’s curriculum collection area, including

flexibility that allows for group work, comfortable seating, natural and task

appropriate lighting and de-centeredness where learning spaces flow (Van Note

Chism, 2006, as cited in Stoddard & Godfrey, 2020). The curriculum

collection area at MRU’s new library was designed to serve as an extension of

the education department’s classrooms with flexible and comfortable seating and

an open space that doubles as an informal gathering area or a classroom.

Instructors sometimes teach in the space or provide students with class time to

walk down the hall and retrieve items to bring back to class. Library classes

are often taught in this area, requiring students to apply critical evaluation

and literacy skills as they examine resources in groups. The goal of this

research is to examine the impact of a very significant and intentional change

in environment and space allocated to the collection and surrounding area.

Researchers formulated survey questions to identify the importance of location

and other space related factors influencing collection use before and after the

move to the new building.

Methodology

This longitudinal study employed exploratory mixed

methods research to examine possible changes in use of this collection over

time. The goal was to try and establish meaningful connections between two sets

of data collected by comparing qualitative survey responses with physical item

circulation data (Chrzastowski &Joseph, 2005;

Creswell, 2003; Hiller & Self, 2001). Ethics approval was granted by Mount

Royal University’s Human Research Ethics Board (HREB). A survey was sent to

students enrolled in a third-year education course (EDUC 3361) in 2017, prior

to the move to a new building. The same student cohort was surveyed in a

fourth-year education course (EDUC 4020) in Winter 2018 after the library

collection was moved to the new building. The survey responses were kept

anonymous, as individual changes in use were less of a concern to the

researchers than growth or patterns in use from the entire cohort. The

rationale behind anonymizing the survey was to reduce the impulse to provide

pleasing or socially desirable responses. The education librarian works closely

with students in this program and has built a rapport with many of the students

surveyed. As a result of this established relationship, the researchers felt

that an anonymous survey would encourage honest responses regarding library use.

Recruitment of participants was based on their enrolment in these courses, as

they are core courses in the Bachelor of Education program, and was conducted

by both investigators during an in-person class visit. Students were encouraged

to complete a short, 7-8 question online survey on the Survey Monkey platform.

The survey questions were developed with spatial triad

theory in mind. The three elements of Lefebvre’s theory - representations of

space/conceived space, spatial practices/perceived space, and representational

spaces/lived space, provided a grounding for our survey questions and data

analysis (Ilako et al., 2020). We attempted to

determine how the design of the new library space occupied by the curriculum

collection (representations of space) affected students’ use. The survey asked

students which factors contributed to increased use, to determine their

perceptions of the space. Through the analysis of qualitative and quantitative

data, the authors assessed whether the students’ perceptions of use (spatial

practices) and actual collection use (representational spaces) were aligned. To

further understand students' experience of the space and collection, we asked

about the purpose of their collection use. While the triad identifies three

elements of space, the interaction of these elements in the production of space

is important to our interpretation of Lefebvre’s theory. The survey included a

question regarding student perceptions of the location and its impact on their

use of the curriculum collection. The questionnaire also had a series of

multiple-choice questions related to how students first learned about the

collection, the purpose of their collection use (with children, for assignments

etc.) and a demographic question about their minor. The 2018 iteration of the

survey included an additional question about what factors, if any, impacted

their use of the collection after the move.

A visual representation of the survey questions

(excluding demographic questions) in relation to each element of the triad

theory has been provided in Figure 1. Interpretations of the theory and its

elements vary in the literature, making the process of categorizing questions

difficult. The intent was not to separate them as they are interrelated. The

decision to locate the collection close to the department was part of the

planning process, but clearly influenced student perceptions (perceived space)

and their use of the space (lived space). The impact of the architecturally

conceived space on students’ perceptions and the influence of these perceptions

on their daily practice or lived spatial experience demonstrates a fluid

process in the production of space. The area was designed to create meaningful

connections between departmental classrooms and the collection area. Furniture

was selected to create an informal classroom and meeting area and the hope was

that the survey questions would prompt students to comment on furniture and

lighting as details that influenced their perception of the area. The goal was

to increase understanding of student perceptions of the space and the majority

of the survey questions were concerned with spatial practice and how students’

perceptions contributed to their actual experience of the space.

In addition to the survey,

physical item circulation data between the period of 2013-2019 was gathered and

analysed. With the assistance of a staff member in the library’s Information

Systems unit, and a staff member in the Collections unit, data was extracted

from the two integrated library systems (Voyager and Alma), in use during the

study period. Transactions which qualified for inclusion included any item that

was signed out by a patron.

Figure

1

Survey

questions mapped to Lefebvre’s spatial triad.

Results

Survey Results

The sample size was small,

with 62 students enrolled in EDUC 3361 in 2017 and 65 students enrolled in EDUC

4020 in 2018. In 2017, 59 students completed the online survey (n=59 or 95%

response rate) and in 2018, 38 students completed the survey (n=38 or 58%

response rate). Responses were migrated from SurveyMonkey into a spreadsheet,

multiple choice answers were tallied, and a content analysis schema was applied

to the text of the short answer/open text responses by two independent coders guided

by pre-established codes and themes.

General

Knowledge of the Collection

Out of the 59 students

surveyed in 2017, 56 (95%) were aware that the collection existed. Again, in

2018, 34 out of 36 (95%) students surveyed said that they knew about the collection.

If students answered no to this question, they were not asked subsequent

questions and the survey ended. This question helped eliminate responses from

students who could not answer the rest of the survey, so sample size changed to

n=56 in 2017 and n=36 2018.

In 2017, 24 (41%) students

indicated that they learned about the library through the education librarian,

while 27 (47%) learned about it through instructor endorsement and 7 (12%)

discovered the collection through their peers. In 2018, responses to this question

shifted as 23 (61%) students indicated that they learned about the collection

through an instructor, followed by the librarian at 32% (12) and 8% (3) from

their fellow classmates. The “power users” of the collection, who used it 10 or

more times, were minoring in Indigenous Studies, Humanities, Math, General

Sciences and Teaching English as a Second Language (TESL), a pattern consistent

in both years.

Student Perceptions of Use

Students were asked to select a number range

reflecting their use of the curriculum collection during the course of their

program (Table 1) as well as the purpose of their use (Table 2).

Factors that Impacted Use

Students were asked a direct question about whether

location had an impact on their use of the curriculum collection. In 2017 (pre

-move), 33% of students said that location did impact use, and 67% of students

surveyed indicated location did not have an impact. In 2018, 44% of students

responded that location had an impact, while 55% said that it did not affect

their use of the collection. Students were asked to list other factors that

impacted their use. The following themes

were identified in their responses:

●

Types of

material available in the collection (suggestions of what we need more of, or

what was useful to them, by way of subject or format)

●

Characteristics

of space (dark corner, “squished aisles”, accessibility, location within the

library)

●

Knowledge of the

collection

●

Proximity to

practicum

●

Proximity to

classes

●

Cost savings

(having access to the collection meant that they did not have to purchase their

own materials)

In response to an open-ended question at the end of

the survey in 2017, several students indicated that they did not learn of the

curriculum collection until later in their degree. As mentioned previously, the

location of the curriculum collection in the old library was not highly

visible, housed at the back corner of the library with very little lighting and

not many workspaces or seating directly adjacent to the collection. In 2018,

almost all qualitative responses were related to the location of the

collection. The primary focus of those responses was on how convenient it was

to access the collection now that it was on the same floor as their classes and

how the space more organized. The data indicates that planning the new building

to locate the curriculum collection adjacent to the collection, so that

students pass it every day to get to their classrooms, has had a positive

impact on their perceived use of the collection.

Table 1

Frequency of

Student Use of Curriculum Collection

|

Number of

times you have used the collection throughout the course of your studies to

date |

2017 Responses |

2018 Responses |

Increase/Decrease |

|

0 |

5 |

2 |

-1.6% |

|

1-5 |

35 |

16 |

-18.23% |

|

6-10 |

12 |

14 |

+16.15% |

|

10 or more |

6 |

6 |

+5.45% |

|

Total

Responses |

58 |

38 |

|

Table 2

Purpose of Student Use of Curriculum Collection

|

For what purpose have you used the curriculum

collection? |

2017 Responses |

2018 Responses |

|

With children outside the program |

31% |

42% |

|

Class work |

78% |

81% |

|

Completion of assignments |

80% |

97% |

|

Practicum |

64% |

44% |

|

Other |

1% |

3% |

Circulation Data Analysis

MRU Library employs a liaison delivery model for

library instruction and maintains a similar model for collection development.

Each program is assigned a subject librarian with an annual collection budget

allocation. The collection allocation formula considers several factors

including number of enrolled students, full time faculty, and circulation data

in the determination of each disciplinary budget. Subject budgets align with

the overall acquisitions budget and, due to the current economic climate, the library

has not seen an increase in the acquisition budget for some time. Annual

acquisitions in all disciplines have primarily attempted to maintain library

collections to support current programs.

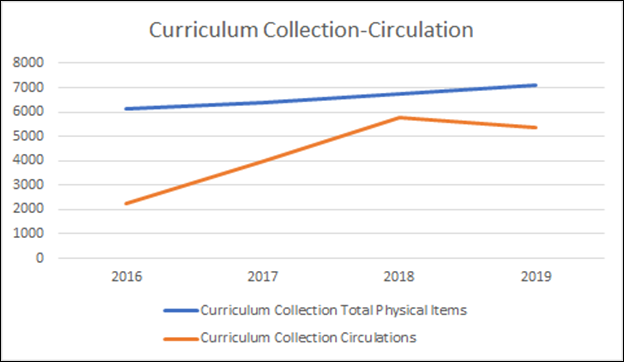

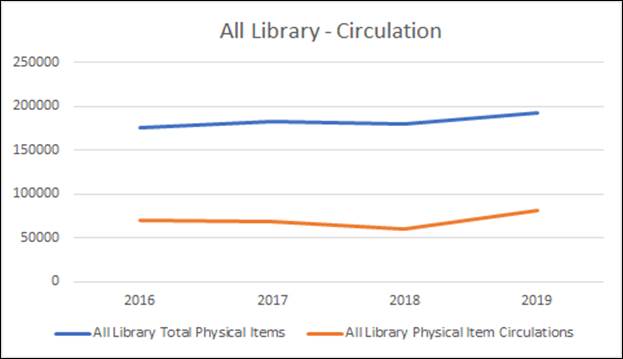

Analysis of circulation patterns reflects steady

growth of the curriculum collection and an increase in the use of the

collection between 2016 (before the move) and 2019. (Figure 2). Items

circulated refers to physical item transactions (charges, recalls, renewals,

holds). We compared curriculum collection circulation of physical items (Figure

2), with overall circulation of the entire library (Figure 3). From 2016-2019

all library circulation statistics remained relatively consistent before and

after the move; 40% of the collection circulated (either browsed or borrowed)

in 2016, 37% in 2017, 33% in 2018, and 42% in 2019. The curriculum collection

saw a significant increase in use immediately after the move to the new

building with 36% of items circulating in 2016,62% in 2017, 85% in 2018, and

75% in 2019.

Figure

2

Total items versus circulations in curriculum collection.

Figure

3

Total items

versus circulations in library.

Discussion

Student Survey Responses

Of the Bachelor of Education students surveyed, 95%

were aware of the collection, once the collection was moved next door to their

classrooms. Of particular interest was the way in which students learned about

the collection. In 2018, survey responses indicated that students learned of

the collection more often from their instructors. When students were asked

about how they used the collection, data reflected increases in use for

supporting in-class work and completing assignments. In both years surveyed, students

who identified as power users (those users who used it ten or more times),

indicated that they also used the collection beyond the classroom and used

materials from the collection for practicum related work or for purposes

directly involving children. Students who used the collection less, generally

responded that they used the collection to support class work or assignments

and remained consistent both years surveyed. The new location is a few metres

from Department of Education classrooms, allowing students to use the space for

group work, study, and completing assignments. The program employs a cohort

model and group assignments are common in many of the required courses (Mount

Royal University, 2020). The results of the survey indicate that those who use

the collection often are taking advantage of the collection and bringing

materials off campus to support their practicums.

Figure 4

Curriculum

collection circulation by user type.

MRU Library applies a liaison librarian model with a

single librarian assigned to a subject area or department in order to provide

teaching, research and collections support. From 2016-2019 the education

librarian delivered an average of 6 library sessions per semester. Library

instruction is always assignment based and as the Bachelor of Education program

is relatively new, assignments change regularly. There was no change in the

education liaison librarian, so the general level of promotion for the curriculum

collection did not vary pre- and post-move. However, after the move, library

instruction delivered to education students took place in department

classrooms, library labs, or the curriculum collection area located directly

adjacent to the department. Before the move, the Department of Education, and

many of the classrooms where library instruction occurred, took place in campus

locations that were a 5–10-minute walk from the library. It is interesting that

after the move there was a shift in how students learned of the collection from

librarian to instructor, which could be indicative of an increase in faculty

knowledge of the collection, faculty use of the collection, or faculty

integration of the curriculum collection into course assignments. Due to data

collection and retention policies at the university, the library collects

limited personal data related to patrons, so it is difficult to identify who is

using the collection and what program they are connected to. We looked at

changes in use according to patron type before and after the move to the new

library and noted that faculty circulation transactions doubled in the course

of four years and that students are the primary users of the collection, with

the greatest increase occurring after the move to the new space (see Figure 4).

There was a noticeable decrease in staff use of the

collection post-move which reinforces the importance of collection proximity.

The library moved from a location in the heart of the main campus building to a

freestanding building on the edge of the campus. While convenience was enhanced

for education students through co-location, convenience decreased for many

staff on campus who, we can surmise based on the data, were deterred by the

walk across campus required to access the collection in the new building.

While the

collection is available to patrons outside of the Department of Education, we

focused on the curriculum collection's intended user group to understand the

impact of co-location and other factors on students' use. Considering the

observable growth in faculty use, and the increase in student responses

indicating faculty endorsement of the collection, it would be worthwhile to

investigate how often the collection is incorporated into assignments. The

increase in community borrower and alumni use is also noteworthy. The RLLC is a

free standing, 4 story building, where the previous library was a single level

space located in the main campus building. The move and new adjacencies with

building partners such as the Department of Education increased convenience and

accessibility for these students, and circulation data also suggests a positive

impact on access and convenience for members of the public and alumni. We built

it and they came.

We asked students about their minor to determine if

there were patterns in subject area use with the goal of providing direction

for future collection development. Correlating minors with use levels was a

challenge because the survey question asked students to respond based on a

numbered range of uses. Students who identified the largest range provided, (10

or more times), were minoring in both arts and humanities-based disciplines

such as Indigenous Studies, Humanities, and Teaching English as a Second

Language (TESL), and STEM disciplines like Math and General Sciences. Previous

studies have indicated that science students are less likely to access library

collections in person while arts students are more likely to use print and

on-site materials (Chrzastowski & Joseph, 2006;

Whitmire, 2002). The responses to this survey could be indicative of faculty

endorsement, disciplinary norms, or requirements for use of the collection in

coursework and assignments.

Students’ Perceptions of Use: Proximity is Everything

Student responses regarding the impact of proximity

are both a reflection of the work of architects, designers, and planners

(representations of space) and the perceived value students place on

convenience and easy access (spatial practice). Other comments refer to the

usefulness of the collection and its relevance to practicum or professional

practice (representational space). Comments illustrate the relationship between

the three elements of the triad. They are inextricably tied to one another as

the meaning students assign to the space evolves from an initial response to

the planners’ location choice, leading to an ease of access for course work.

Students proclaimed “love” and appreciation for the space and collection led to

its incorporation into practicum and course work contributing to the production

of space.

“The new location for the curriculum

collection is easy to access and organized in a fashion that is easy to

navigate. The central location and organized sections have made it more

accessible and easier to utilize.”

“I enjoy

going to the new location better, so I find myself near the curriculum

collection more often.”

“Easier

access”

“Classes

were all in the library building so (sic) was never out of my way to visit.”

“Before

it moved, I did not use it because I was unaware of where it was”.

“It has

because it is in closer proximity to where I study.”

Proximity emerged as the most significant factor in

students’ increased use of the Curriculum Collection. It was apparent that

after the move to the new location adjacent to their classrooms, students were

using the collection with greater frequency (Table 1). Because of the change in

proximity, the collection became more visible to its target user group which

had a positive impact on awareness and use of the collection. This reinforces

the idea that physical proximity can have a positive effect on academic

libraries’ ability to serve their users (Freiburger

et al., 2016). Circulation data verified a substantial increase in use between

2016 and 2018. This increase aligns with student responses and with the

literature on library space improvement and increased use of an academic

library collection.

Figure 5

Student comments mapped to Lefebvre’s

Spatial Triad Theory.

Survey responses, however, suggest some confusion on

the part of students about consistent definition of terms. Convenience was used

interchangeably with proximity, which speaks to the likeliness that in the

lives of students these terms may be equivalent. Students frequently referred

to space as a limiting factor in accessing the collection. The physical space

in the new library has been identified as a significant improvement by

visitors, but students made few references to the space itself as a factor in

their increased use of the collection. An open and bright space with tables,

carrels, comfortable seating, and group rooms contrasts significantly with the

crowded, dark corner previously used to house the collection. The survey

questions did not prompt students to consider these specific factors in their

assessment of increased use of the collection. While students in the pre-move

survey indicated that location impacted use, questions were not specific enough

about whether it had a negative or positive effect. Certain questions on the

survey could have been asked differently and might have elicited more

informative and specific responses related to space.

Limitations

During the process of coding qualitative responses, it

was discovered that there were some omissions and minor flaws in the wording

and specificity of the survey questions. While maintaining a Likert scale, the

same cohort could have been asked to describe their range of perceived use in

the year surveyed, not the duration of their studies, assuming that as students

progress through their degree, their library use would only have increased.

Also, there was growth in the collection over the 3-year period from which

circulation data was extracted and analysed, and a larger or more improved

collection could have contributed to the increase in students’ use. Analysis of

circulation data showed an increase in use specific to user type, but privacy

restrictions mean the program to which students and faculty are attached cannot

be determined. Without that data it is not possible to assign the increase in

circulation to education students with perfect certainty. A review of

transactions by patron type pre- and post-move also reveals that other

borrowers are using the collection. Librarians’ definitions of terms may differ

from students. Providing definitions at the start of the survey for terms like

“use” ensures clearer and more meaningful responses (Kidston, 1985). There was

also an expectation that students would have elaborated in their responses

regarding the improved space. If the survey was redeployed, questions would

provide details specific to lighting, furniture, and study spaces to determine

if these were additional factors that impacted use. Some students mentioned

these factors within their responses, but not to the extent anticipated.

Other

Considerations - Academic Branch and Specialized Collections

Recent branch closures and consolidation in academic libraries

underscore the importance of identifying the value of locating

discipline-specific collections close to the departments they support. In 2004,

Hiller reported on a series of measures used at University of Washington to

evaluate the viability of branch libraries. He predicted the acceleration of

branch library closures and mergers with the exception of those serving

programs that are “dependent on print collections and that provide space that

supports students work in a collaborative teaching and learning environment”

(p. 131). Curriculum collections fall into the category of libraries that rely

on print and physical objects, but this has not protected them from mergers.

More recently, McCullough (2017) identified branch consolidation as a long-term

trend in the context of academic libraries’ response to budget reductions, the

shift to electronic collections, and campus space concerns. Evidence relating

to use patterns and the integration of library material into course assignments

and curriculum are crucial, particularly in light of de-funding, and budget

cuts. When assessing the closure of branch libraries, budget concerns and low

circulation statistics inform part of those decisions. Branch closures or

amalgamations with larger libraries can have a variety of negative impacts on

university library systems, including a decline in overall use of print or

physical resources, a negative perception of service, and a decrease in

requests for information literacy instruction (Lange et al., 2015). Sometimes

the notion of “library as a place” or the intrinsic value of a physical space

offers value despite low circulation statistics or gate counts. However, even

high-use branches that serve large student populations are subject to closures.

University of Alberta Coutts Library, a branch library serving the faculties of

education and kinesiology, was recently closed due to budget cuts (Lachacz, 2020). High circulating collections that consist

of physical books and manipulatives are clearly not exempt from this trend.

Curriculum collections, or other specialized collections that rely heavily on

the circulation of physical resources and student use of physical spaces, have

been identified as vulnerable to branch consolidation (Zdravkovska,

2011). Budget concerns are driving branch consolidations in the face of

evidence presented by many studies suggesting that these high-use branches

serve their users more effectively when they are in close proximity to their

corresponding department or faculty (Locke, 2007; Hiller, 2004).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that a particular user group’s

use of a collection and space, in this case undergraduate Bachelor of Education

students, is significantly impacted by how they perceive the space that houses

the collection. Participants in this study demonstrated a change in their

perception of a discipline specific collection after a significant improvement

was made to the library space housing the collection. The curriculum

collection, which was in an unfavourable and inconvenient library location,

distant from classrooms and education department offices, was used less

frequently prior to the Library’s move to a new building. Once the curriculum collection was relocated,

adjacent to the Department of Education, where the collection’s primary,

intended user group gathered for classes, circulation statistics increased. In

their survey responses, students identified proximity to the collection as

having a positive impact on their use of the collection. This reinforces

Lefebvre’s spatial triad theory describing how conceived space is directly

related to perceived and lived space. A question remains regarding the

particular meanings or social significance assigned to the current space and

how these may be controlled or prompted by course curriculum or assignment

requirements. An exploration of the incorporation of the collection into the

education curriculum will provide a more comprehensive understanding of factors

contributing to student use of the space and collection. The investigators are

currently collecting data in the second part of this study, investigating how

education faculty use the collection in their teaching and assignments.

Readers may find it useful to consider the power of

Lefebvre’s theory to provide a lens through which to understand how library

space planning contributes to the production of space where users assign

meaning in the completion of their course and professional work. Leckie and

Given (2010) state that “the relationship between perceived, conceived and

lived are not linear and not stable but rather are fluid and dynamic” (pp.

228-229). The curriculum area examined in this study is not a static space and

will continue to evolve to meet users’ curricular and professional needs. A

future study may provide opportunities to understand how the space and

collection can serve as a more effective extension of the classroom and

education program curriculum, allowing users to challenge our original design

and create a more meaningful lived space. Lefebvre’s theory has provided a

context for the cyclical nature of space production as challenges provide users

with the opportunity to produce and reproduce space.

Important issues came to the attention of the

researchers indirectly during this study.

Responses from students suggested that there could be a connection

between increased student use and the incorporation of the collection into

assignments and course curriculum. After the move, faculty increasingly

recommended the collection to students and developed assignments that required

the use of curriculum resources. The researchers will endeavour to explore use

patterns among user groups and survey faculty about changes in how they

incorporate the curriculum collection into teaching and assignments. A future

study that investigates the relationship between student collection use with

curriculum integration could provide deeper insight into how the collection is

being used. This point of inquiry was identified through the triangulation of

survey and circulation data, which provided a more complete picture of how the

collection was being used, or in Lefebvre’s terms, how the space was produced.

Knowing how faculty and students are integrating physical collections into

their course work and assignments will inform space planning and librarians’

collection development and teaching practices to meet users’ needs more

effectively. There is also a growing number of branch and specialized

collection closures and consolidations occurring in academic libraries.

Evidence of the importance of collection proximity to academic programs and

integration with student learning may inform future management of these spaces

and difficult decisions related to closures.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Jenny Joe, ILS Programmer Analyst, Mount

Royal University for assisting with data ILS data extraction; and Margy MacMillan, & Richard Hayman for feedback and

comments.

Author

Contributions

Pearl Herscovitch:

Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal), Visualization (equal),

Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing Madelaine Vanderwerff:

Conceptualization (equal), Data curation, Formal analysis (equal),

Investigation (equal), Methodology, Visualization (equal), Writing – original

draft (equal)

References

Albanese, R.A. (2003).

Deserted no more: After years of declining usage statistics, the campus library

rebound. Library Journal, 128(7), 34-36.

Bailin, K. (2011). Changes in

academic library space: A case study at the University of New South Wales. Australian Academic & Research Libraries,

42(4), 342-359. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2011.10722245

Bodolay, R., Frye, S.,

Kruse, C., & Luke, D. (2016). Moving from co-location to cooperation to collaboration.

In Space and Organizational

Considerations in Academic Library Partnerships and Collaborations (pp.

230–254). https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-0326-2.CH011

Cha, S. H., & Kim, T. W.

(2015). What matters for students' use of physical library space? The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 41(3), 274-279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.03.014

Chrzastowski, T. E., &

Joseph, L. (2006). Surveying graduate and professional students' perspectives

on library services, facilities and collections at the University of Illinois

at Urbana-Champaign: Does subject discipline continue to influence library use?

Issues in Science & Technology

Librarianship, 45, 12.

Connaway, L., Dickey,

T., & Radford, M. (2011). “If it is too inconvenient I’m not going after

it:” Convenience as a critical factor in information-seeking behaviours. Library & Information Science Research.,

33(3), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2010.12.002

Curriculum Materials

Committee, Education and Behavioral Sciences Section, ACRL. (2017).

Guidelines for Curriculum Materials Centers.

Creswell, J. W., Plano

Clark, V. L., Gutmann, M. L., & Hanson, W. E. (2003). Advanced mixed

methods research designs. Handbook of mixed

methods in social and behavioral research, 209, 240.

Defrain, E. & Hong,

M. (2020). Interiors, affect, and use: How does an academic library’s learning

commons support students’ needs? Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice, 15(2), 42-68. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29677

Fleming-May, R. (2011). What

is library use? Facets of concept and a typology of its application in the

literature of library and information science. The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, 81(3),

297–320. https://doi.org/10.1086/660133

Freiburger, G., Martin, J.

R., & Nuñez, A. V. (2016). An embedded librarian

program: Eight years on. Medical reference

services quarterly, 35(4),

388-396. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2016.1220756

Gardner, S., & Eng, S. (2005). What students want: Generation Y and the

changing function of the academic library. Portal: Libraries and the Academy, 5(3), 405-420. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2005.0034

Given, L., & Leckie, G.

(2003). “Sweeping” the library: Mapping the social activity space of the public

library. Library & Information Science Research, 25(4), 365–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(03)00049-5

Hiller, S., & Self, J.

(2001). A decade of user surveys:

Utilizing and assessing a standard assessment tool to measure library

performance at the University of Virginia and University of Washington

[Conference Session]. 4th Northumbria Conference. Washington, DC. https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/bitstream/1773/19920/1/Northumbria%202001%20PM4.pdf

Hiller, S. (2004). Measure

by measure: Assessing the viability of the physical library. The Bottom Line, 17(4), 126-131. https://doi.org/10.1108/08880450410567400

Holder, S., & Lange, J.

(2014). Looking and listening: A mixed-methods study of space use and user

satisfaction. Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice, 9(3), 4-27.

https://doi.org/10.18438/B8303T

Ilako, C., Bukirwa,

M. & Maceviciute, E. (2020). Relevance of the

spatial triad theory in (re) designing and planning of academic library

spaces. Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries, 9(1), 65-75.

Julien, H., & Michels, D. (2004). Intra-individual information behaviour

in daily life. Information Processing

& Management, 40(3), 547-562. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(02)00093-6

Kennedy, J. (2008).

Anonymity. In P. J. Lavrakas (Ed.), Encyclopedia of

survey research methods (pp. 27-28). Sage. http://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963947

Kidston, J. S. (1985). The

validity of questionnaire responses. The

Library Quarterly, 55(2), 133-150. https://doi.org/10.1086/601589

Lachacz, A. (2020, June

4). Breaking: U of A closes Coutts Library; marks second library closure due to

budget cuts. The Gateway. https://thegatewayonline.ca/2020/06/breaking-u-of-a-closes-coutts-library-marks-second-library-closure-due-to-budget-cuts/

Lange, J., Lannon, A., & McKinnon, D. (2014). The measurable

effects of closing a branch library: Circulation, instruction, and service

perception. Portal: Libraries and

the Academy, 14(4), 633-651. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2014.0031

|

|

Leckie, G. & Given, L.

(2010). Henri Lefebvre and spatial dialectics. In G. Leckie, L. Given & J. Buschman (Eds.), Critical

theory for library and information science: exploring the social from across

the disciplines (pp. 221-236). Libraries Unlimited.

Lefebvre, H. (1992). The

production of space (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). Wiley Blackwell.

(Original work published 1974)

Locke, R. (2007) More than

puppets: Curriculum collections in Australian universities. Australian Academic and Research Libraries,

38 (3), 192-215. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2007.10721296

Martell, C. (2008). The

absent user: Physical use of academic library collections and services

continues to decline 1995–2006. The

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 34(5),

400-407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2008.06.003

May, F., & Swabey, A. (2015). Using and experiencing the academic

library: A multisite observational study of space and place. College & Research Libraries, 76(6), 771-795. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.6.771

McCreadie, M. & Rice,

R.E. (1999). Trends in analyzing access to

information. Part I: Cross-disciplinary conceptualizations of access. Information Processing & Management, 35(1),

45-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4573(98)00037-5

McCullough, I. & Calzonetti,

J. (2017). Are they different? An

investigation of space and learning in a STEM branch library. In S. Montgomery

(Ed.), Assessing library space for

learning (pp. 143-166). Rowman &

Littlefield.

Mount Royal University.

(2020). Department of Education practicum

& field experience. https://www.mountroyal.ca/ProgramsCourses/FacultiesSchoolsCentres/HealthCommunityEducation/Departments/Education/practicum-field-experience/index.htm

Shill, H. B., & Tonner,

S. (2004). Does the building still matter? Usage patterns in new, expanded, and

renovated libraries, 1995–2002. College

& Research Libraries, 65(2),

123-150. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.65.2.123

Savolainen, R. (2006).

Spatial factors as contextual qualifiers of information seeking. Information Research: An International

Electronic Journal, 11(4), 2.

Stoddart, R., & Godfrey,

B. (2020). Gathering evidence of learning in library curriculum center spaces

with eb GIS. Evidence Based Library and

Information Practice, 15(3), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29721

Teel, L. (2013).

Transforming space in the curriculum materials center. Education Libraries, 36(1), 4-14.

Whitmire, E. (2002).

Disciplinary differences and undergraduate’s information‐seeking behavior. Journal of the American Society for Information

Science and Technology, 53(8),

631-638. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.10123

Zdravkovska, N. (2011). Academic branch libraries in changing times.

Elsevier. http://doi.org/10.1016/b978-1-84334-630-2.50005-8

Zieleniec, A. (2013).

Space, social theories of. In B. Kaldis (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Philosophy & the Social

Sciences (Vol. 1, pp. 953-955). Sage. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781452276052

Zieleniec, A. (2007). Space and social theory. Sage. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446215784