Research Article

Moral Distress Among Consumer Health Information

Professionals: An Exploratory Study

Robin O'Hanlon

Associate Librarian, User

Services

Memorial Sloan Kettering

Cancer Center Library

New York, New York, United

States of America

Email: ohanlonr@mskcc.org

Katelyn Angell

Associate

Professor/Coordinator of Library Instruction

Long Island University,

Brooklyn Campus Library

Brooklyn, New York, United

States of America

Email: Katelyn.Angell@liu.edu

Samantha Walsh

Manager of Information &

Education Services

Levy Library

Icahn School of Medicine at

Mount Sinai

New York, New York, United

States of America

Email: Samantha.walsh@mssm.edu

Received: 10 Oct. 2020 Accepted: 5 Apr. 2021

![]() 2021 O’Hanlon, Angell, and Walsh. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2021 O’Hanlon, Angell, and Walsh. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Data Availability: O'Hanlon,

R., Angell, K., Walsh, S. (2021). Raw dataset and interview codebook for

"Moral Distress Among Consumer Health Information Professionals: An

Exploratory Study"[Dataset]. Edmonton, Canada: UAL Dataverse.

Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.7939/DVN/LZHZHC

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29871

Abstract

Objectives – In recent

years, moral distress has become a topic of interest among health

professionals. Moral distress is most commonly described in the nursing

literature, and refers to a situation wherein an individual knows the correct

action to take, but is constrained from doing so. While moral distress differs

from the classic ethical dilemma, in recent years practitioners and theorists

have advocated for a broadening of the definition of moral distress. To date,

no study has examined another group of individuals who frequently interact with

patients and who may be constrained by the confines of their role - Consumer

Health Information Professionals (CHIPS). The objective of this study was to

determine if CHIPS experience moral distress and/or ethical dilemmas, and to

determine what, if any, coping strategies these individuals have developed.

Methods – This study employed a mixed methods approach.

Quantitative data were gathered via an online survey which was distributed to

relevant consumer health information professional electronic mail lists. The

survey contained demographic questions and a series of questions related to

potential discomfort within the context of work as a consumer health

information professional. Qualitative data were also gathered through phone

interviews with CHIPS. Interview questions included the participant’s

definition of moral distress, professional experiences with moral distress, and

any coping strategies to manage said distress.

Results – The authors

received 213 survey responses. To test whether any of our demographic variables

help to explain survey response, we used STATA to calculate Pearson correlation

coefficients. Individuals who were more likely to experience discomfort in

their occupation as CHIPS included individuals with less experience and

individuals who identified as Black and Latinx. Interview data indicated that

participants most commonly experienced ethical dilemmas related to censorship,

providing prognosis information, and feeling constrained by institutional policies.

Few interview participants described scenarios that reflected moral distress.

Conclusions – CHIPS do

not appear to experience moral distress, at least according to its most narrow

definition. CHIPS do consistently experience distinct ethical dilemmas, and the

most durable patterns of this phenomenon appear to be related to experience

level and racial identity. In recent years, researchers have raised calls to

broaden the definition of moral distress from its narrow focus on constraint to

include uncertainty, and CHIPs do experience moral uncertainty in their work.

Further study is needed to determine how to best address the impacts of

discomfort caused by ethical dilemmas among these groups.

Introduction

Originally discussed in nursing literature, the concept

of moral distress is evolving and has more recently been explored in various

healthcare professions. In 1984, Andrew Jameton

described moral distress as a phenomenon that arises “when one knows the right

thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue

the right course of action” (Jameton, 1984, p. 6).

While Jameton and his contemporaries’ discourse

focused on the experiences of nurses, researchers have become interested in

exploring this concept outside of the nursing profession, as well as beyond

situations involving an institutional constraint. Fourie (2015) sought to

expand the definition of moral distress beyond nurses and experiences of

constraint, proposing that moral distress occurs when health professionals

experience a psychological response due to a moral conflict, restraint, or

uncertainty.

While

this evolved definition allows us to explore the experiences of all healthcare

workers, it is important to understand the difference between moral distress,

moral conflict, and ethical dilemmas. Moral conflict occurs when “when duties

and obligations of healthcare providers or general guiding ethical principles

are unclear” (Jormsri, 2004, p. 217), while an

ethical dilemma involves “the need to choose from among two or more morally

acceptable options or between equally unacceptable courses of action, when one

choice prevents selection of the other” (Ong et al., 2012, p. 11). Ethical

dilemmas and moral conflicts are often closely related to the experience of

moral distress in healthcare professionals. As these concepts are explored and

refined, the authors of this study sought to understand the experience of

Consumer Health Information Professionals (CHIPS). CHIPS are information

professionals providing consumer health information, or health information to

non-healthcare professionals, in a variety of settings (Reference and User

Services Association, 2015). Working in public, hospital, and other specialized

libraries, these professionals regularly interact with patients and families at

distressing times. While there is a growing interest in moral and ethical

issues within the Library and Information Sciences profession, information

professionals who provide healthcare information to the public have not been

the focus of a study on moral distress. These information professionals

frequently interact with patients in a variety of settings, and may be

constrained by their role, resources, or institution. Furthermore, one author personally

experienced a feeling of constraint while assisting a patron with a consumer

health information inquiry.

Literature

Review

Beginning

in the 1980’s, the majority of studies exploring moral distress consider the

experiences of nurses. This continued focus is because Jameton’s

formative definition of moral distress necessitates the existence of

“institutional constraints” (1984, p. 6). Many researchers describe nurses as

particularly prone to situations where they must carry out and often bear the consequences

of others’ decisions (Marshall & Epstein, 2016). Similarly, the Moral

Distress Scale, developed by Corley (1995), which measures nurses’ experiences

of moral distress, focuses on various limitations of agency, such as

“institutional constraint.” Exploring nurses’ experiences using the Moral

Distress Scale as well as other measures, researchers have found that moral

distress manifests in various forms of psychological distress as well as

physical manifestations. In a recent review, Morley, Ives, and Bradbury-Jones

(2019) report “sleeplessness, nausea, migraines, gastrointestinal upset,

tearfulness and physical exhaustion” (p. 655) in nurses experiencing moral

distress. This phenomenon also has a direct effect on patient care, as Oh and Gastmans’ (2015) report that nurses with a high level of

moral distress experience depersonalization, where they emotionally distance

themselves from patients. Finally, moral distress is a documented threat to the

healthcare workforce itself, as Whitehead, Herbertson,

Hamric, Epstein, and Fisher (2015) reported that “providers who had left or

considered leaving a position in the past reported moral distress mean levels

significantly higher than those who had never considered leaving” (p. 123). It

is important to note that Whitehead et al.’s survey included all healthcare

professionals in the authors’ healthcare system.

In

recent years, researchers have studied moral distress in non-nursing healthcare

professions, such as healthcare assistants (Rodger, Blackshaw,

& Young, 2019), veterinarians (Moses, Malowney,

& Wesley Boyd, 2018), medical students (Camp & Sadler, 2019), physician

trainees and residents (Dzeng et al., 2015; Sajjadi, Norena, Wong, & Dodek, 2016), and Oncologists (Hlubocky,

Spence, McGinnis, Taylor, & Kamal, 2020). This research is happening in

tandem with the evolution of Jameton’s formative

definition, as evidence of moral distress is becoming apparent across

healthcare fields. Like many nursing researchers, Sajjadi

et al. (2016) also report an increased likelihood to leave the job or

profession in internal medicine residents experiencing high levels of moral

distress. While we are beginning to appreciate the prevalence of moral distress

among a variety of patient-facing healthcare workers, studies have not focused

on the experiences of CHIPS.

At

the time of this writing, Library and Information Science (LIS) literature has

reported very little research on moral distress and moral conflict. Most

research on the broader topic of the distinction between right and wrong within

matters relating to the profession has focused primarily on ethical dilemmas.

Despite the fact that research nearly 30 years ago explored “moral conflict” as

experienced by librarians, recent scholarship has not expanded upon this topic

much. This is particularly surprising within health and medical librarianship,

as broader medical literature continues to assess related concepts of morality.

This paper can help contribute to the development of a body of knowledge on

morality within library and consumer health information literature.

In

1993 Broderick describes 19th century librarians as self-defined “moral

arbiters” (p. 447) of society, responsible for determining appropriate and

inappropriate information for their constituencies. Framed in the context of

collection development, the central thesis of the piece is the obligation of

public libraries to shirk the idea of a universal morality and acquire

materials with myriad points of view on a subject. Low (2002) also examines moral

conflicts within collection development, specifically related to the tension

film librarians can face when deciding between acquiring movies featuring a

diverse array of perspectives and dominant preferences of the library’s parent

company. He argues that true morality cannot exist in a library collection

“without recognizing all voices, i.e. without a balance of perspectives” (p.

40).

However,

ethical dilemmas have been repeatedly addressed in various library settings,

including hospital, academic, and public. Librarians experience ethical

quandaries across departments and roles, including reference services (Luo

& Trott, 2016), reader’s advisory (Lawrence, 2020), the organization of

information (McCourry, 2015), privacy/confidentiality

(Elliott, 2015), and RFID technology (Thornley, Ferguson, Weckert,

& Gibb, 2011). Some researchers are generating strategies for preparing

people to resolve ethical dilemmas before they even complete their LIS graduate

programs. Walther (2016) details the development of problem-based learning

techniques to teach LIS graduate students critical skills for handling ethical

dilemmas in their future careers. This pedagogy is framed in part by the

definition of an ethical l dilemma as occurring when “two or more moral

obligations come into conflict” (Walther, p.181).

Murphy

(2001) elucidates ethical dilemmas faced by hospital librarians, chiefly the

pressure to choose between prioritizing the needs of their institution versus

collective social welfare, or the mores of the broader library profession. The

stakes are high here, as the actions of hospital librarians directly impact the

physical and psychological well-being of patrons (patients and their loved

ones). Rigorous training in and dissemination of the professional ethics of the

field can help this disconnect. Professional codes, such as the Medical Library

Association’s Code of Ethics for Health Sciences Librarianship (last updated in

2010), can play an important role in individually or collaboratively working

through job-related ethical dilemmas.

In

2014 Byrd, Devine, and Corcoran surveyed 500 MLA members and learned that while

80% of respondents knew of the Code, nearly one third were unaware when they

last consulted it for guidance. While clearly an invaluable resource for

information professionals, the Code’s principles do not directly address

morality within informed decision making. One participant of this study, when

surveyed on key issues that the Code does not explicitly cover, responded that

“honesty, fairness and morality” (p. 269) should be added as principles that

librarians are professionally obligated to follow.

Aims

The impetus for this study was grounded first and

foremost in a combination of shared professional and close personal connections

with nurses, as well as professional experiences as information professionals.

One author identified a feeling of moral distress caused by constraint in

assisting a patron with a consumer health information inquiry, and began to

construct a project to deeper examine these experiences. All three authors have

encountered ethical dilemmas in the course of either providing consumer health

information services or teaching research skills to nursing students.

Two research questions can be used to frame this study.

First, do CHIPS experience moral distress or ethical dilemmas while performing

their daily job duties? Secondly, if

individuals experience moral distress or ethical dilemmas, what coping

strategies, if any, have they developed?

Methods

The

study employed a mixed methods approach. In April 2020, the study was

determined to meet the regulatory exemption for IRB by Memorial Sloan Kettering

Cancer Center’s Human Research Protection Program under 45 CFT.101(d)(2).

Contemporary

moral distress instruments (e.g., the Moral Distress Scale-Revised) are heavily

focused on issues surrounding direct patient care, which may not be applicable

to CHIPS. As a result, we developed an instrument using the secure web

application REDCap.

The survey contained questions on basic demographic and

occupational questions along with a series of questions designed to measure

feelings of discomfort and distress within the context of consumer health

information librarianship. To assess personal values, the survey also asked

belief-oriented questions related to patient advocacy and empowerment.

Non-demographic questions were posed on a Likert scale from 1-6 (1 = Strongly

Disagree; 2 = Disagree; 3 = Mildly Disagree; 4 = Mildly Agree; 5 = Agree; 6 =

Strongly Agree). The survey instrument has been included as Appendix A. The

survey questions were primarily intended to measure CHIPS’ experiences of

ethical dilemmas. However, because of the somewhat ambiguous nature of

moral/ethical phenomena, some of the survey questions could address both

ethical dilemmas and moral distress, depending on how the respondent

interpreted the question. For example, for question #3

(“I feel licensing agreements with vendors prohibit me from sharing information

with patients in the way I would like”) one could argue that a respondent who

“agrees” or “strongly agrees” with this statement is experiencing moral

distress because he/she/they feels that providing free and unencumbered access

to information for all consumers is the morally correct course of action, and

feels constrained by licensing agreements. This person may, on

moral grounds, feel that all information should be free and that any barriers

to openness are morally reprehensible. However, one could also argue that a

respondent who “agrees” or “strongly agrees” is experiencing an ethical dilemma

if they feel that both choices are morally acceptable and

simply don’t know which to choose. This respondent might respect the legality

of restrictions to proprietary information and feel they have these

restrictions have value, but at the same time may wish their patrons could have

free access.

The survey was disseminated in early May 2020 and

remained open to responses until June 16, 2020. It was disseminated to 22

electronic mail lists geared towards medical, academic, and public library

information professionals. No incentive was offered for completing the survey.

STATA was used to complete statistical analysis. The raw survey data has been

openly deposited.

Survey respondents had the option to include their

contact information if they wished to participate in a follow-up interview.

While the survey assessed if CHIPS were experiencing distress in general, the

aim of the interviews was to determine if the distress CHIPS experience occurs

within the context of moral distress or ethical dilemmas.

Interview questions were open ended and focused on three

components: 1) the participant’s understanding and personal definitions of

moral distress, 2) the participant’s experience with moral distress in the

context of being a consumer health information professional, 3) any coping

strategies the participant had developed to manage moral distress. Interviews

continued until a saturation point in thematic information was reached,

resulting in 14 total interviews. Due to time constraints, only one author

coded the interviews. Interviews were manually coded in a Google sheet,

resulting in 21 codes. Wherever possible, the author used rich or thick

descriptions assessing the interview data, making the code descriptions as

detailed as possible. Appendix B includes the interview schedule. The interview

codebook has been openly deposited with the raw data.

Interviews were conducted by one author using Zoom. Prior

to the interviews, participants received informed consent documentation. Phone

interviews were recorded and transcribed using TapeACall

Pro software. Zoom interviews were recorded and manually transcribed.

Interviews completed by phone were automatically transcribed using the TapeACall Pro transcription feature, but required some

manual cleanup. Interviews took place in May 2020 and June 2020.

Survey Population and Demographics

Consumer health information (CHI) is defined as

“information on health and medical topics provided in response to requests from

the general public, including patients and their families. In addition to

information on the symptoms, diagnosis and treatment of disease, CHI

encompasses information on health promotion, preventive medicine, the determinants

of health and accessing the health care system” (Reference and User Services

Association, 2015). Any professional working in this role and self-identifying

as a CHIP qualified to participate in this study.

The authors received 213 survey responses; Table 1

presents summary statistics of this sample. The majority of the respondents

identified as female (81%); white (62%); had a MLS, MIS, or MLIS degree

(66.2%); or had an MLS, MIS, or MLIS and another advanced degree (16.9%),

bringing the total of respondents who had an MLS, MIS, or MLIS to 83%.

Respondents were aged 41-60 (49%), and were not licensed as medical

professionals (94%). Ten respondents preferred not to provide either racial

identity (3.3%) or gender identity (1.4%) and were excluded from the regression

analyses. Respondents were mainly employed by academic medical centers (43%),

hospitals (28%), and public libraries (16%). The amount of experience among

respondents was fairly evenly distributed, 8-20 years’ experience was most

frequently reported (30%), and over 20 years’ experience the least frequently

reported (21%).

In order to understand how our sample compared to the

overall population, we examined data from a demographic survey of Medical

Library Association members (Pionke, 2019). We found

that compared to the respondents in the MLA survey (n=918), our respondents

identified as being less white (62% vs. 72%), slightly more female (81% vs.

79%), and were similar in age range. It should be noted, however, that only 1%

of the respondents in the MLA study identified “consumer health” as their

primary job function.

Table

1

Sample

Characteristics

|

|

N |

% |

|

Age |

|

|

|

Under

25 |

5 |

2.3% |

|

25-30 |

16 |

7.5% |

|

31-40 |

35 |

16.4% |

|

41-50 |

50 |

23.5% |

|

51-60 |

56 |

26.3% |

|

61-70 |

40 |

18.8% |

|

70+ |

11 |

5.2% |

|

Gender

Identity |

|

|

|

Female |

173 |

81.2% |

|

Male |

33 |

15.5% |

|

Gender

non-binary |

4 |

1.9% |

|

Prefer

not to say |

3 |

1.4% |

|

Racial

Identity |

|

|

|

White/Caucasian |

133 |

62.4% |

|

African

American/Black |

24 |

11.3% |

|

Hispanic/Latinx |

24 |

11.3% |

|

Asian

American/Asian |

12 |

5.6% |

|

American

Indian/Alaska Native |

1 |

0.5% |

|

Native

Hawaiian/Pacific Islander |

0 |

0.0% |

|

Middle

Eastern/North African |

2 |

0.9% |

|

Prefer

not to respond |

7 |

3.3%% |

|

Other/not

provided |

10 |

4.7% |

|

Educational

Background |

|

|

|

Master

of Library and Information Science/Master of Library Studies/Master of

Information Studies |

141 |

66.2% |

|

MLS,

MLIS, or MIS AND other advanced degree (i.e. other master’s degree or

doctoral degree) |

36 |

16.9% |

|

Advanced

degree (i.e. other master’s degree or doctoral degree), not MIS, MLIS, or MLS |

18 |

8.4% |

|

Other |

11 |

5.2% |

|

Undergraduate

degree only |

7 |

3.3% |

|

Medical License |

|

|

|

Does

not have a medical license |

201 |

94.4% |

|

Does

have a medical license |

12 |

5.6% |

|

Years of

Consumer Health Experience |

|

|

|

Less

than 12 months |

8 |

3.8% |

|

1-4

years |

39 |

18.3% |

|

4-8

years |

39 |

18.3% |

|

8

years-15 years |

53 |

24.9% |

|

15

years-20 years |

29 |

13.6% |

|

20

years-25 years |

22 |

10.3% |

|

25

years-over 35 years |

23 |

10.8% |

|

Years in

Current Position |

|

|

|

Less

than 12 months |

12 |

5.6% |

|

1-4

years |

60 |

28.2% |

|

4-8

years |

40 |

18.8% |

|

8

years-15 years |

43 |

20.2% |

|

15

years-20 years |

28 |

13.2% |

|

20

years-25 years |

15 |

7.0% |

|

25

years-over 35 years |

15 |

7.0% |

|

Type of Institution Where Employed |

|

|

|

Private

hospital |

5 |

2.4% |

|

Not-for-profit

hospital |

45 |

21.1% |

|

Community

hospital |

6 |

2.8% |

|

Academic

medical center |

48 |

22.5% |

|

Academic

library |

39 |

18.3% |

|

Community

health center |

0 |

0% |

|

Government

agency |

17 |

8.0% |

|

Public

library |

30 |

14.1% |

|

Unemployed |

1 |

0.47% |

|

Other |

22 |

10.3% |

Results

Table 2 presents average Likert scores (1 = Strongly

Disagree, 6 = Strongly Agree), standard deviations, and overall proportions of

responses for questions relating to moral distress. High average Likert scores

(5+) indicate that the majority of respondents overwhelmingly agreed or

strongly agreed with a particular statement. For example, respondents expressed

strong preferences for patient rights (90.6% agreed or strongly agreed that

patients should have access to as much health information as they wish; 92.9%

agreed/strongly agreed that health professionals should take an active role in

patient education and engagement). Similarly, these variables report small

standard deviations (less than 1), indicating that the distribution of Likert

scale responses is highly bunched.

Conversely, low average Likert scores (less than 3) were

more common on questions which emphasized CHIP unpreparedness. Over half of the

sample disagreed with the statements “I often feel unable to provide patients

with the health information they are looking for” and “I often worry that I

lack the necessary skills, education or knowledge.” However, standard

deviations on these “disagree” statements were larger (1.4 and 1.5,

respectively), indicating more variability in response.

While clear majorities emerged in response to certain

issues, respondents were also divided around numerous issues. A fairly even

split in agreement and disagreement can be seen in response to the question

regarding patients confusing the role of the information professional with the

role of a health care provider and not having enough time to spend with

patients. About a third of respondents said they did not feel pressured to

provide prognosis information to patients, or provide them with positive

information about their prognosis, but respondents were likely to feel that

they often must inform patients that the information resources they have

located on their own were not evidence based.

Similarly, responses related to institutional pressure

were mixed. While almost a quarter of respondents agreed with the statement

that licensing agreements prohibited sharing information with patients, more

than one quarter disagreed with this statement. Even though one third of

respondents did not feel torn between the different constituencies they worked

with, nearly 44% reported feeling frustrated with the many roles they were

expected to perform.

Table

2

Likert Scores

|

Question |

% Strongly Disagree |

% Disagree |

% Mildly Disagree |

% Mildly Agree |

% Agree |

% Strongly Agree |

|

"I often

feel unable to provide patients with the health information they are looking

for." |

16.9% n=36 |

37.6% n=80 |

10.8% n=23 |

17.8% n=38 |

14.6% n=31 |

2.3% n=5 |

|

"I often

worry that I lack the necessary skills, education, or knowledge to provide

patients with the information they are looking for." |

16.9% n=36 |

38% n=81 |

10.8% n=23 |

15% n=32 |

13.1% n=28 |

6.1% n=13 |

|

"I feel

like licensing agreements with vendors prevent me from sharing information

with patients in the way I would like." |

16.0% n=34 |

26.3% n=56 |

8.0% n=17 |

15.5% n=33 |

24.4% n=52 |

9.9% n=21 |

|

"I often

feel like patients confuse my role with their health care provider." |

9.4% n=20 |

27.2% n=58 |

10.3% n=22 |

15.5% n=33 |

29.1% n=62 |

8.5% n=18 |

|

"I often

feel like I do not have adequate time to spend on search requests for

patients." |

10.8% n=23 |

28.2% n=60 |

10.8% n=23 |

14.1% n=30 |

26.3% n=56 |

9.9% n=21 |

|

"I often

feel pressured to provide prognosis information or survival rates for

patients." |

16.4% n=35 |

30% n=64 |

12.2% n=26 |

11.3% n=24 |

24.4% n=52 |

5.6% n=12 |

|

"I often

feel patients expect me to provide them with positive information about their

prognosis." |

8.5% n=18 |

31.0% n=66 |

12.2% n=26 |

17.8% n=38 |

22.1% n=47 |

8.5% n=18 |

|

"I often

feel I must inform patients the resources they have found on their own are

not evidence based, credible or reliable." |

3.8% n=8 |

11.3% n=24 |

6.1% n=13 |

17.8% n=38 |

41.3% n=88 |

19.7% n=42 |

|

“I often feel

torn between the different constituencies (e.g. patients, administrators,

clinicians) with whom I work.” |

7.5% n=16 |

33.3% n=71 |

9.9% n=21 |

16.9% n=36 |

22.5% n=48 |

9.9% n=21 |

|

"I feel

frustrated with the many roles I am expected to perform." |

7% n=15 |

25.4% n=54 |

7.5% n=16 |

16% n=34 |

29.1% n=62 |

15% n=32 |

|

"I often

feel caught in the middle between trying to appease patients, caregivers, and

their own health care providers." |

11.7% n=25 |

17.8% n=38 |

12.2% n=26 |

16.4% n=35 |

33.3% n=71 |

8.5% n=18 |

|

"I am

able to successfully cope with the challenges of my position." |

2.3% n=5 |

11.3% n=24 |

5.6% n=12 |

16.4% n=35 |

54% n=115 |

10.3% n=22 |

|

"My

library has an adequate budget." |

8.9% n=19 |

26.8% n=57 |

8.9% n=19 |

14.1% n=30 |

33.3% n=71 |

8% n=17 |

|

"My

library has adequate staff with expertise in providing consumer health

information services." |

8.4% n=18 |

28.2% n=60 |

10.3% n=22 |

20.2% n=43 |

28.2% n=60 |

4.7% n=10 |

|

"I am

able to acquire the resources I need to meet the information needs of my

users." |

2.3% n=5 |

40.4% n=86 |

9.9% n=21 |

17.8% n=38 |

21.6% n=46 |

8% n=17 |

|

"I have

been concerned for my physical or mental health during times of emergency

(e.g., terrorist attacks, pandemics, natural disasters) at my library." |

8.5% n=18 |

24.4% n=52 |

9.9% n=21 |

22.5% n=48 |

21.6% n=46 |

13.1% n=28 |

|

"The

administration of my organization understands the value and importance of my

library." |

9.4% n=20 |

24.9% n=53 |

6.6% n=14 |

14.1% n=30 |

33.3% n=71 |

11.7% n=25 |

|

"I

believe patients and caregivers should have access to as much health information

as they wish." |

0% n=

0 |

1.9% n=4 |

2.3% n=5 |

5.2% n=11 |

33.8% n=72 |

56.8% n=121 |

|

"I

believe patients and caregivers should be active advocates for their own

health care." |

0% n=

0 |

0% n=

0 |

1.4% n=3 |

5.2% n=11 |

33.3% n=71 |

60.1% n=128 |

|

"I

believe health professionals should take an active role in patient education

and engagement." |

0% n=0 |

0.5% n=1 |

0.5% n=1 |

6.1% n=

13 |

32.9% n=70 |

60.1% n=128 |

Regression Analysis

To test whether any of our demographic variables help to

explain survey response, we used Stata 14 to calculate Pearson chi-squared

tests of independence. Response patterns about patient access and advocacy were

systematically different by racial identity in a statistically significant

manner (χ2=27.4, p=.007 and χ2=18.2, p=.033). Similarly, men tended to disagree

more with the idea that health professionals should take a role in educating

patients, and that they were being asked to provide prognosis information

(χ2=29.8, p=.000 and χ2=23.9, p=.008). Figure 1 displays a spineplot

for the results, by gender, for the question "I often feel pressured to provide prognosis information or

survival rates for patients." Figure 2 presents the question results

by racial identity. Spineplots were created in Stata,

utilizing a software package designed by Cox (2008).

Those who worried about being unprepared were

statistically more likely to be the young (χ2=58.1, p=.000, for the variable

“unprepared,” and χ2=84.1 , p=.000 for the variable “imposter”) and those in

the field for shorter durations ( χ2=25 p=.049 for the variable “unprepared” and χ2=45.7 p=.000 for the variable “imposter”).

We also found that those who identify as Black or Latinx are more likely to

feel frustrated with role confusion when it concerns their jobs as CHIPS ( χ2=54 , p=.000). These racial identity groups also report

that they feel required to provide positive responses to patron inquiries, to

provide prognosis information, and are more likely to fear for their safety

while at work in statistically significant patterns (χ2=84.1 , p=.000, χ2=86.6

, p=.000, and χ2=56.7 , p=.000).

Interview Data Characteristics

Fourteen interviews were conducted and interview

participants were first asked to give their personal definition of moral

distress. Some interviewees gave definitions that closely matched the “classic”

definition of moral distress, but more often their definitions were more

closely aligned with a moral or ethical dilemma. Some interviewees were unable

to provide a clear definition, but instead referred to a survey question that

particularly resonated with them. This resulted in 4 original definitions

provided during the 14 interviews.

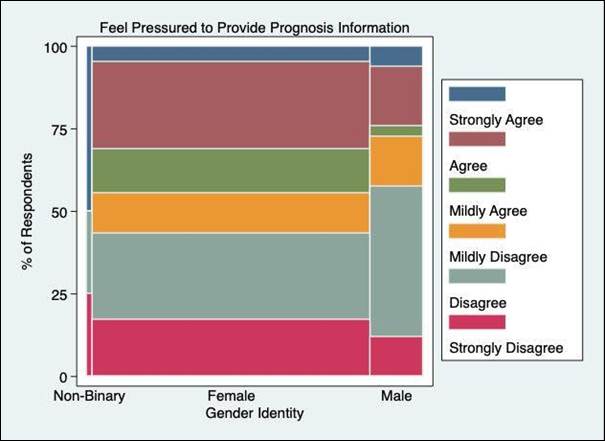

Figure 1

Respondents’ perceptions of providing prognosis

information by gender.

Figure 2

Respondents’ perceptions of

providing prognosis information by racial identity.

The authors asked interview participants to identify how

they experienced moral distress in their work as CHIPS, and several themes

emerged. The first centered around role confusion, wherein consumers do not

understand the purpose of the consumer health library or the role of the

consumer health information professional, and do not recognize that the

consumer health information professional is not a health professional.

Respondents noted that this role confusion usually manifests in patrons seeking

specific medical advice or recommendations from them, including dosing

information for medications or interpreting medical test results.

Several interview participants reported feeling

discomfort when having to inform patients that the information they have found

on their own was not evidence based. In doing their own health information

research, consumers may find health information and then desire “confirmation”

from a consumer health information professional that the information they have

found is in fact evidence based. Respondents report this is more common when

patients are seeking alternative or integrative therapies in place of, rather

than in complement to, traditional medicine. Another common source of internal

conflict among the interview participants related to being asked to provide

prognosis information including survival rates/outcomes:

"I have that

mental list of diagnoses that I want people to not ask me. Because I know what

the situation looks like, pancreatic cancer, for example. I hate it. Especially

in a case like that, when survival rates aren't good, but they don't know that

yet. So they are just looking at treatment situations or whatever. And I never

know how far to go. Like should I be offering them information on palliative

care?”

Several interview participants raised the issue of

providing “too much” information, particularly when assisting patients who were

newly diagnosed with a condition that has particularly dire outcomes.

Participants reported not wanting to “overwhelm” their patrons with information,

but feeling that not providing them with the level of information requested

would amount to censorship:

"I… worry

about inadvertently being a censor, not providing them with enough information

for them to make a health care decision because I know they're not at a place

where they can do that effectively."

A lack of available information on a particular health

topic was also often a source of discomfort for interview participants. In this

instance, assisting individuals with rare diseases and conditions can be

particularly challenging. Other participants reported frustration with being

unable to find health information resources available in languages other than

English.

Interview participants described several instances

wherein they struggled with institutional policies to remain “neutral:”

“The Library can't

recommend one [health care] facility over another, even though I might know

that one facility has a worse record on something. And that I struggle with,

too, so I'm always saying get a second opinion, look at other places. Here are

the statistics."

One interview participant described a scenario wherein

despite being hired as a “community health librarian,” she had been constrained

by the administration of her institution from actively providing services to

the local community and was instead relegated to providing services to a lower

need community that was directly affiliated with her institution (a

university).

While not directly related to ethical constraints or

dilemmas, interview participants reported several scenarios related to their

work as CHIPS that caused them to feel a sense of generalized distress. Two

interview participants felt they lacked the necessary training and skills to

function competently in their positions and that they experienced feeling of

inadequacy and stress. Finally, interview participants reported that simply

being exposed to the stress of patients, caregivers, and family members can be

upsetting, particularly if they have not received adequate training to cope

with these types of stressors:

"They come in

with a diagnosis, and I'll help them, it's not a good diagnosis, and they'll be

upset. You're trying to help them, and they start crying. They're visibly

upset, which makes me upset."

Interview participants identified several coping

strategies for managing their experiences of moral distress, as well as

emotional distress in the professional setting. Six interview participants

reported relying on a network of professionals for additional support when the

patron they were helping was in distress or if the patron asked for

resources/information beyond the scope of the consumer health information

professional’s role. These professionals include social workers, patient

advocates, volunteer services, patient educators, and dieticians. One

respondent noted the benefits of support from health care providers:

"It's good to

have nurse colleagues who can help me process things, and know how to deal with

weird situations, like being pulled into people's medical and legal issues. As

librarians we want to help, so it's helpful because they know where to refer

people for things like living wills."

Participants reported strengthening their professional networks over

time, as they became more familiar with institutional resources and personnel.

Several participants reported that they simply felt less distress as they

gained familiarity with the types of encounters and requests that typically

upset them, and as they became more comfortable with the demands of their role

and their surroundings. Using a disclaimer (either verbally or in a written

form such as a sign) which described the role of the consumer health

information professional and its limitations was also reported.

Working to ensure patients are effective advocates for

their own health was another coping strategy reported by participants. One

subject described alleviating discomfort by encouraging the patients he worked

with who were feeling overwhelmed by their diagnosis to write down specific

questions they have for their health care provider and to practice asking them

aloud. Other participants reported encouraging patients to bring research

studies or consumer health information they had located to their health care

provider. Other coping strategies were less frequently reported and included

indulging in escapist entertainment, using reflective practice (e.g.,

journaling), using institutional staff assistance programs, and actively

circumventing bureaucratic systems to aid their patrons.

Discussion

The study finds that CHIPS do experience generalized

distress within their professional roles, and in some cases this distress

appears to be directly related to the nature of their role. For example, one

interview participant described her struggle with providing information on

Morgellons Disease, a controversial condition which many health professionals

describe as a form of delusional parasitosis, but has also been described by a

smaller group of medical professionals as a legitimate dermatological

condition. The controversial nature of the condition left this interview

participant feeling torn between her patrons who were convinced they suffered

from the condition and the lack of evidence that the condition actually exists

in the physical sense. CHIPS exist within a sort of interspace, with

significantly more expertise of health information than the average consumer,

but frequently without the licensure, education, and hands on knowledge of

medical professionals. Navigating this interspace may prove challenging,

particularly for individuals who are already faced with navigating

organizational power structures and systemic pathologies (ex., racism, ageism).

Indeed, the distress experienced by consumer health

professionals appears to be related at least in part to the level of support,

or lack thereof, that they receive from their institution at large. While the majority

of respondents felt they were able to successfully cope with the challenges of

their positions (54%), one third reported that their library had an inadequate

budget (33%), inadequate staffing to support consumer health information

services (33%), and that the administration of their organization did not

understand the value and importance of their library (33.3%). About a third

(34.7%) of respondents also reported being concerned for their physical or

mental health during times of an emergency.

While CHIPS appear to experience distress, it is

beneficial to distinguish between distress that occurs in the course of one’s

occupation and distress caused by an ethical

dilemma in a professional context. Again, an ethical dilemma is a situation

in which two moral principles conflict with one another. Not all the scenarios

described by the interview participants were true ethical dilemmas, but some

were, including concerns about censorship, providing prognosis information, and

feeling constrained by institutional policies. The latter phenomenon, a feeling

of institutional constraint, is associated with moral distress, but our

interview participants were more likely to experience scenarios with competing

moral drawbacks, rather than one obvious morally superior option. The most

durable patterns of these experiences of ethical dilemmas appear to be related

to experience level and racial identity.

CHIPS do not appear, though, to experience moral

distress, at least according to its narrow definition (knowing the correct

action to take, but being constrained from doing so by external forces). Why

don’t CHIPS experience moral distress? One reason may be that the key component

of moral distress, as traditionally defined, of “constraint” is less likely to

be present. It may be that case that the constraint CHIPS experience within the

course of their profession is felt less acutely than frontline medical

professionals, such as nurses, who are directly responsible for the health and

safety of patients. It also appears that CHIPS may confuse moral distress and

ethical dilemmas, or conflate the two.

If moral distress is defined more broadly, as suggested

by Fourie (2015), one could argue that CHIPS do indeed experience a degree of

moral distress. Fourie argues that we should recognize that “constraint is not

a necessary condition of moral distress and that such distress can arise from

morally troubling situations other than those of moral constraint” (p. 580) and

that moral distress should be expanded to include experiences related to moral

uncertainty.

Limitations

The authors acknowledge that the study is limited by

several factors. First, because there was no validated instrument to measure

moral distress and ethical dilemmas among consumer health professionals, we did

not use a validated tool. In future research, a validated tool may aid in

further distinguishing between the nuanced and complex experiences of moral

distress and ethical dilemmas. The purposive sampling technique used

(leveraging electronic mail lists of interest to CHIPS) to identify potential

survey respondents may have resulted in a degree of selection bias. Finally,

only one interviewer coded the interviews. Using two or more coders in future

studies would reduce the potential for bias when identifying interview themes,

as long as proper interrater reliability protocols are implemented.

Further Research

While

this study provides burgeoning insight into the exploration of moral distress

among CHIPS, additional research is needed to validate and expand on these

findings to draw broader conclusions.

First,

it would be valuable for outside researchers to apply the survey instrument

developed by the authors to their own samples. The instrument was used for the

first time in the present study, and did not undergo validity or reliability

calculations. This process would help to ensure the instrument is consistent

across applications, measures what it intends to measure, and that results can

be extrapolated to a broader population.

Next,

the results of the survey indicated that participants who are Black or Latinx

experience greater distress in the CHI profession than people of other racial

identities. These statistics are concerning and need further investigation in

efforts to identify and ameliorate any racism or microaggressions causing this

distress. While there aren’t similar studies within LIS scholarship to compare

these findings Dyo, Kalowes,

and Devries (2016) found that Hispanic nurses reported much higher rates of

moral distress than other ethnic groups, “suggesting that culture and ethnicity

may play a role in the perception and experience of moral distress” (p. 1). A

pertinent solution identified within nursing literature to address this problem

was to begin studying moral distress as experienced by non-Western nurses (Prompahakul & Epstein, 2020), a project that could

easily be replicated with CHIPS or librarians.

Conclusions

This study examined how CHIPS experience moral distress,

ethical dilemmas, and the use of coping strategies for managing the negative

impacts of these phenomena. While the study finds that CHIPS do not appear to

experience moral distress according to its narrow definition focused on

constraint, study results indicate that CHIPS do experience ethical dilemmas in

the course of their work. The most durable patterns of ethical distress

experienced by CHIPS appear to be related to experience level and racial identity,

with younger, Black, and Latinx CHIPS experiencing ethical dilemmas at higher

rates. Further study is needed to determine why there is a statistically

significant relationship between these groups and their experiences with

ethical distress. The interview data further elucidates how CHIPS interpret the

phenomenon of moral distress and how this term is sometimes confused with

ethical dilemmas. This issue could be ameliorated by professional associations

creating a module on integral ethical codes of their area of librarianship and

encouraging libraries to include participation in the module in onboarding for

new hires. Additionally, Library and Information Science graduate programs can

build greater content on morals and professional ethics into their foundational

courses. Finally, while the experiences of the study participants do not fit

the classic definition of moral distress, which is characterized by the

presence of constraint, they do align with a more broadly defined version of

moral distress. This definition, as described by Fourie (2015) allows for the

inclusion of the experience of uncertainty to co-exist with the experience of

constraint in moral contexts.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all survey respondents

and interview participants. Many thanks to Kendra Godwin for her assistance

with reviewing the survey prior to distribution, and thanks to Tedi Brash, Aman Kaur, Barnaby Nicolas, Robb Mackes, and Shawn Stedinger for

their assistance with survey distribution.

The authors would like to thank Sam Stabler for his

assistance with statistical analysis and creating the spineplots.

Author Contributions

Robin O’Hanlon:

Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Visualization, Writing – original

draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal) Katelyn Angell:

Methodology, Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing

(equal) Samantha Walsh: Methodology, Writing – original draft (equal),

Writing – review & editing (equal)

References

Broderick, D. M. (1993). Moral

conflict and the survival of the public library. American Libraries, 24(5),

447–448. https://www.jstor.org/stable/i25632891

Byrd, G. D., Devine, P. J.,

& Corcoran, K. E. (2014). Health sciences librarians' awareness and

assessment of the Medical Library Association Code of Ethics for Health

Sciences Librarianship: The results of a membership survey. Journal of the Medical Library Association:

JMLA, 102(4), 257–270. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.102.4.007

Camp, M., & Sadler, J.

(2019). Moral distress in medical student reflective writing. AJOBEmpirical Bioethics, 10(1), 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/23294515.2019.1570385

Corley, M.C. (1995). Moral

distress of critical care nurses. American

Journal of Critical Care, 4(4),

280–285. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc1995.4.4.280

Cox, N. J. (2008). Speaking

Stata: Spineplots and their kin. The Stata Journal, 8(1),

105-121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0800800107

Dyo, M., Kalowes, P., &

Devries, J. (2016). Moral distress and intention to leave: A comparison of

adult and paediatric nurses by hospital setting. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing, 36,

42-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2016.04.003

Dzeng, E., Colaianni, A., Roland,

M., Levine, D., Kelly, M., Barclay, S., & Smith, T. (2015). Moral distress

amongst American physician trainees regarding futile treatments at the end of

life: A qualitative study. Journal of

General Internal Medicine, 31(1),

93-99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3505-1

Elliott, K. (2015). Planning

for barriers in hospital library social media implementation. Journal of Hospital Librarianship, 15(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15323269.2015.982013

Fourie, C. (2015). Moral

distress and moral conflict in clinical ethics. Bioethics, 29(2), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12064

Hlubocky, F. J.,

Spence, R., McGinnis, M., Taylor, L., & Kamal, A. H. (2020). Burnout and

moral distress in oncology: Taking a deliberate ethical step forward to

optimize oncologist well-being. JCO

Oncology Practice, 16(4),

185–186. https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.20.00030

Jameton, A.

(1984). Nursing practice: The ethical

issues. Prentice Hall.

Jormsri, P.

(2004). Moral conflict and collaborative mode as moral conflict resolution in

health Care. Nursing & Health

Sciences, 6(3), 217-221. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2004.00191.x

Lawrence, E. E. (2020). On the

problem of oppressive tastes in the public library. Journal of Documentation, 76(5),

1091–1107. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-01-2020-0002

Low, D. (2002). Moral conflict

for the film librarian. Journal of

Information Ethics, 11(2), 33-45.

https://ir.uwf.edu/islandora/object/uwf:23834

Luo, L., & Trott, B.

(2016). Ethical issues in reference: An in-depth view from the librarians’

perspective. Reference & User

Services Quarterly, 55(3),

189–198. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.55n3.188

Marshall, M. F., & Epstein,

E. G. (2016). Moral hazard and moral distress: A marriage made in purgatory. The American Journal of Bioethics: AJOB,

16(7), 46–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2016.1181895

McCourry, M. W. (2015). Domain analytic, and domain

analytic-like, studies of catalog needs: Addressing the ethical dilemma of

catalog codes developed with inadequate knowledge of user needs. Knowledge Organization, 42(5), 339–345. https://doi.org/10.5771/0943-7444-2015-5-339

Medical Library Association

(2010). Code of ethics for health

sciences librarianship. https://www.mlanet.org/page/code-of-ethics

Morley, G., Ives, J., Bradbury-Jones, C.,

& Irvine, F. (2019). What is ‘moral distress’? A narrative synthesis of the

literature. Nursing Ethics, 26(3), 646–662. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733017724354

Moses, L., Malowney,

M. J., & Wesley Boyd, J. (2018). Ethical conflict and moral distress in

veterinary practice: A survey of North American veterinarians. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine,

32(6), 2115–2122. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.15315

Murphy, S.A. (2001). The

conflict between professional ethics and the ethics of the institution. Journal of Hospital Librarianship, 1(4),

17-30. https://doi.org/10.1300/J186v01n04_02

Oh, Y., & Gastmans, C. (2015). Moral distress experienced by nurses:

A quantitative literature review. Nursing

Ethics, 22(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733013502803

Ong, W. Y., Yee, C. M., &

Lee, A. (2012). Ethical dilemmas in the care of cancer patients near the end of

life. Singapore Medical Journal, 53(1), 11–16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22252176/

Pionke, JJ. (2019). Medical Library Association Diversity and

Inclusion Task Force 2019 survey report. Journal

of the Medical Library Association, 108(3), 503–512. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2020.948

Prompahakul, C., & Epstein, E. G. (2020). Moral distress

experienced by non-Western nurses: An integrative review. Nursing Ethics, 27(3),

778–795. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733019880241

Reference and User Services

Association (2015). Health and medical

reference guidelines. http://www.ala.org/rusa/resources/guidelines/guidelinesmedical

Rodger, D., Blackshaw,

B., & Young, A. (2019). Moral distress in healthcare assistants: A

discussion with recommendations. Nursing

Ethics, 26(7–8), 2306–2313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733018791339

Sajjadi, S., Norena, M., Wong, H.,

& Dodek, P. (2017). Moral distress and burnout in

internal medicine residents. Canadian Medical

Education Journal, 8(1), e36–e43.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28344714/

Thornley, C., Ferguson, S., Weckert, J., & Gibb, F. (2011). Do RFIDs (radio

frequency identifier devices) provide new ethical dilemmas for librarians and

information professionals? International

Journal of Information Management, 31(6),

546–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2011.02.006

Walther, J. H. (2016). Teaching

ethical dilemmas in LIS coursework: An adaptation on case methodology usage for

pedagogy. The Bottom Line, 29(3),

180-190. https://doi.org/10.1108/BL-05-2016-0020

Whitehead, P.

B., Herbertson, R. K., Hamric, A. B., Epstein, E. G.,

& Fisher, J. M. (2015). Moral distress among healthcare professionals:

Report of an institution-wide survey. Journal

of Nursing Scholarship: An Official Publication of Sigma Theta Tau

International Honor Society of Nursing, 47(2),

117–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12115

Appendix

A

Survey

Instrument

How

old are you?

Under

25

25-30

31-40

41-50

51-60

61-70

Over

70

What

is your gender?

Female

Male

Gender

non-binary

Prefer

not to say

Which

of these best describes your racial identity?

African

American/Black

American

Indian/Alaska Native

Asian

American/Asian

Native

Hawaiian/Pacific Islander

Hispanic/Latinx

Middle

Eastern/North African

White/Caucasian

Other/Not

Provided

Prefer not to respond

What

is your educational background?

Master

of Information Science

Master

of Library and Information Science

Master

of Library Science

Advanced

degree (i.e., other masters degree or

doctoral

degree), not MIS, MLIS, or MLS

MLS,

MLIS, or MIS AND other advanced degree

(i.e.,

other masters degree or doctoral degree)

Undergraduate

degree only

Other

If

"Other," please describe.

Are

you currently, or have you ever been, a licensed medical professional (e.g.

Registered Nurse, Medical Doctor)?

Yes

No

If

you are currently or have been licensed medical professional in the past,

please describe:

Years

of consumer health librarian experience/providing health information to the

public:

Less

than 12 months

1

year - 2 years

2

years - 4 years

4

years - 6 years

6

years - 8 years

8

years - 10 years

10

years - 12 years

12

years - 15 years

15

years - 20 years

20

years - 25 years

25

years - 35 years

Over

35 years

Years

in current position:

Less

than 12 months

1

year - 2 years

2

years - 4 years

4

years - 6 years

6

years - 8 years

8

years - 10 years

10

years - 12 years

12 years

- 15 years

15

years - 20 years

20

years - 25 years

25

years - 35 years

Over

35 years

Type

of institution where you are employed:

Private

hospital

Not-for-profit

hospital

Community

hospital

Academic

medical center

Academic

library

Community

health center

Government

agency

Public

library

Unemployed

Other

If

"Other," please describe.

For the remaining questions, please select one of the following values that

best describes how

you

feel about each statement below:

Strongly

Disagree

Disagree

Mildly

Disagree

Mildly

Agree

Agree

Strongly

Agree

1)

I

often feel unable to provide patients with the health information they are

looking for.

2)

I

often worry that I lack the necessary skills, education, or knowledge to

provide patients with the information they are looking for.

3)

I

feel licensing agreements with vendors prohibit me from sharing information

with patients in the way I would like.

4)

I

often feel that patients confuse my role with their health care provider.

5)

I

often feel I do not have adequate time to spend on search requests for

patients.

6)

I

often feel pressured to provide prognosis information or survival rates for

patients.

7)

I

often feel patients expect me to provide them with positive information about

their prognosis.

8)

I

often feel I must inform patients the resources they are have found on their

own are not evidence

based,

credible, or reliable.

9)

I

often feel torn between the different constituencies (e.g. patients,

administrators,

clinicians)

with whom I work.

10)

I

feel frustrated with the many roles I am expected to perform.

11)

I

often feel caught in the middle between trying to appease patients, caregivers,

and their health care

providers.

12)

I

am able to successfully cope with the challenges of my position.

13)

My

library has an adequate budget.

14)

My

library has adequate staff with expertise in providing consumer health

information services.

15)

I

am able to acquire the resources I need to meet the information needs of my

users.

16)

I

have been concerned for my physical or mental health during times of emergency

(e.g. terrorist

attacks,

pandemics, natural disasters) at my library.

17)

The

administration of my organization understands the value and importance of my

library.

18)

I

believe patients and caregivers should have access to as much health

information as they wish.

19)

I

believe patients and caregivers should be active advocates for their own health

care.

20)

I

believe health professionals should take an active role in patient education

and engagement.

Contact

information (Optional)

If

you are willing to participate in a phone interview about moral distress and

consumer health librarianship, please include your contact information (name

and email address). Any information professional who provides health

information to the public can participate. If you decide to participate in a

phone interview, your

information

will by anonymous in the final publication.

Please

ONLY include your contact information if you are interested in participating in

a phone interview. If you are not interested in participating in a phone

interview, leave this section blank.

Appendix B

Interview Schedule

- Can you define “moral distress”?

- a) Do you feel you have ever experienced

moral distress in your role as a consumer health librarian (or as an

information professional who provides health information to the public)?

b)

If yes, in what ways have you experienced moral distress in your role as a

consumer health librarian (or as an information professional who provides

health information to the public)?

c)

If yes, how has your experience of moral distress affected your ability to

function in your job and your attitude toward your job?

- a) If you have experienced moral distress

in the course of your profession, what factors have contributed to your

distress (e.g., number of years of experience, type of patient)?

b)

If you have not experienced moral distress in your profession, how do you feel

you have avoided this phenomenon?

- a) If you have experienced moral distress

in the course of your profession, have you employed to lessen your

experience of moral distress?

b)

If you have employed coping strategies, which strategies did you find the most

effective

and why?