Research Article

Information Services in Evidence Based Medical Education: A Review of Implementation Trends

Sedigheh Khani

Ph.D. Candidate in Medical

Librarianship and Information Sciences

School of Health Management

and Information Sciences

Iran University of Medical

Sciences

Tehran, Iran

Email: khani.se@iums.ac.ir; khani.sedigheh@gmail.com

Sirous Panahi

Associate Professor

Department of Medical

Library and Information Science

School of Health Management

and Information Sciences

Iran University of Medical

Sciences

Tehran, Iran

Email: panahi.s@iums.ac.ir

Ali Pirsalehi

Assistant Professor of

Internal Medicine

Clinical Development

Research Center of Taleghani Hospital

Medical School

Shahid Beheshti Medical

University

Tehran, Iran

Email: pirsalehi@sbmu.ac.ir

Ata Pourabbasi

Assistant Professor

Endocrinology and Metabolism

Clinical Sciences Institute

Tehran University of Medical

Sciences

Tehran, Iran

Email: Atapoura@tums.ac.ir

Received: 7 Oct. 2021 Accepted: 26 Apr. 2021

![]() 2021 Khani, Panahi, Pirsalehi,

and Pourabbasi. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2021 Khani, Panahi, Pirsalehi,

and Pourabbasi. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29860

Abstract

Objective – Evidence based

medical education requires supportive information services to facilitate access

to the needed educational evidence. Information services designed specifically

for evidence based medical education are limited or locally developed for

educational units. For librarians to have an opportunity to cooperate

efficiently with medical educators in evidence based medical education, they

require an empirical prototype for transmission of clinical evidence at the

right place and the right time. Therefore, there is a need to recognize types

of information services which support evidence based medical education. The

purpose of this review is to identify implementation trends of evidence based

educational information services.

Methods – We found

related studies by implementing search strategies in PubMed, EMBASE, Web of

Science, Scopus, LISTA, and Google Scholar with keywords like: evidence based

medical education, information services, and library services. We used

reference-checking and citation-checking of related articles for completing the

process of locating relevant articles. After employing inclusion and exclusion

criteria, we selected 11 articles for inclusion in the review and analyzed them

using a narrative review technique.

Results – After

analyzing the results of the included studies, we identified two elements

categorized as program development and five elements categorized as

implementation trend. Prerequisites of program and the process of designing

were essential parts of program development of information services. Schedule

and type of access, how to receive educational-clinical questions, information

services types, responding time, and providing evidence based

outputs were the elements of the implementation process of educational

supported information services.

Conclusion – Designing an evidence based

educational information service strongly depends on the information needs of

learners at each educational level. Schedule and type of access to information

service, time of responding to the received query, and preparation of evidence

based output are essential factors in designing practical educational-developed

information services.

Introduction

In

the 1990s, David Sackett introduced the concept of evidence based medicine

(EBM). EBM was defined as the use of up-to-date, best evidence in clinical

decision making for a better understanding of causation and prognosis of

disease, and selecting more appropriate diagnostic tests and treatment

strategies based on patient preferences and the clinical condition of the

patient (Sackett et al., 1996). In the practice of EBM, clinicians complement

their clinical expertise with the best available evidence (Sackett et al.,

1996), which evidence is available from systematic clinical research like

systematic reviews, cohort studies, and randomized control trials (Burns et

al., 2011).

EBM

and its applications in different functions of medicine have empowered the medical

community (Djulbegovic

& Guyatt, 2017; Sur & Dahm, 2011). Medical

practice, healthcare management, clinical research, and of course, medical

education has been affected by EBM principles (Djulbegovic

& Guyatt, 2017; Shortell et al., 2007). Evidence Based

Education/Best Evidence in Medical Education (EBE/BEME) makes an effort to

utilize evidence in education (Davies, 1999) and reshape the practices and

approaches of learner training based on the best available evidence (Harden et al.,

2000; Hart & Harden, 2000). The goal of

EBM in clinical practice is to enhance patient treatment, but in medical

education, educators train learners in the practice of EBM to empower them to

use evidence in clinical practice (Guyatt et al.,

1992).

Medical

educators try to have an updated and evidence based approach to their teaching

practice in processes such as curriculum revision or implementing new

instructional techniques (Poirier &

Behnen, 2014). In the

evidence based paradigm of teaching, educators combine up-to-date, quality

evidence with previous experience and current educational approaches (Chessare, 1996). Typical tasks required for

evidence based practice in medical education include phrasing a question,

designing a search strategy, appraising the evidence, and making the required

intervention in the teaching approaches (Davies, 1999; Harden

et al., 2000; Hart & Harden, 2000). A primary

challenge of the above procedure is searching the published literature (Poirier &

Behnen, 2014).

Finding

the best evidence is one of the main challenges of EBE/BEME for medical

educators; often they need assistance to effectively find required evidence (Chessare, 1996;

Harden et al., 2000; Reed et al., 2005). Difficulty in

accessing the empirical educational knowledge has a multidimensional nature.

Medical instructors have expressed some barriers to implementing evidentiary

information in education. Lack of time for finding evidence based knowledge,

the volume of research evidence, lack of educational evidence, lack of access

to evidence based educational databases, and difficulty in finding educational

evidence were found to be obstacles for accessing relevant evidence (Emami et al.,

2019; Onyura et al., 2015; Sandars & Patel, 2015; Suttle et al., 2015; Thomas

et al., 2019). Searching for

evidence consists of two core challenges: how to search for evidence and where

to search for evidence (Haig &

Dozier, 2003a, 2003b).

Information

services fulfill the need for access to evidence in medical practice. The main

purpose of information services in a health system is to enhance the

decision-making of clinicians in the treatment of patients. The actors of an

information service are skilled librarians, and the core activity of

information services is transforming requests for evidence into relevant,

evidence based information which then impacts clinical decision making (Fennessy, 2001). In the process of evidence

based decision making, information services with different implementation

trends were developed to supply qualified and up-to-date evidence for

healthcare practice.

Jordan

and Porritt (2004) established an information service to provide evidence based

information for clinicians and patients. The information service supported both

access to evidence and education for how to utilize what they could access.

MCMASTER+ was another type of evidence based information service, which

organized information based on evidence hierarchy and facilitated finding

required evidence to address related clinical questions (Holland &

Haynes, 2005). McGowan et al.

(2010) developed an information service to provide evidence for primary care

practitioners and enhance clinical decision making. These information services

to support clinical practice had commonalities in their implementation

processes. For example, the process of developing reference services for

clinicians consisted of two main components: first, selecting and adapting

appropriate technology, and second, training the librarian to deliver the

information service. Most of the information services supporting clinical

decision making were developed on the web with a well-defined, user-friendly

interface that enhanced physician access to the best evidence (Holland &

Haynes, 2005; Jordan & Porritt, 2004; McGowan et al., 2010). The process of

delivering needed evidence began from searching, appraising, and summarizing

evidence to transferring it into

practice (Davies et al.,

2017; Holland & Haynes, 2005; Jordan & Porritt, 2004; McGowan et al.,

2010), and reviewing

and updating collected evidence periodically (Jordan &

Porritt, 2004).

Aims

All

of the above evidence based information services were

established for clinical practice, but providing evidence for medical education

needs its own educational-developed information services (Emami et al.,

2019; Onyura et al., 2015). Onyura et al. (2015) stated that the delivery approaches

for evidence based knowledge currently available were insufficient and there

was a need for new approaches for delivering synthesized evidence that have a

concise presentation and are accessible at the point-of-need. In this respect,

identifying the implementation trends of information services designed for

evidence based education can be prototypical for designing evidence based

information services for medical education.

Based

on the hierarchy of information services in the Library, Information Science

& Technology Abstracts (LISTA) database thesaurus (EBSCO, n.d.-a),

information services are developed to fulfill information needs in various

fields such as business, agriculture, community, education, and more. In the

LISTA thesaurus, “information services in education” was defined as the “use of

data storage, organization, search, retrieval, and transmission services in

education” (EBSCO, n.d.-b). In the current study, we identified search,

retrieval, and transmission aspects of information services in education.

Therefore, the aim of this review was to identify the types of information

services that were provided for EBE/BEME and compare the trends of supplying

evidence for supporting student teaching and learners training under the

concept of Evidence Based Educational Information Services (EBEIS).

Methods

Article Selection

We

accessed studies on information services that supported EBE/BEME by searching

databases and performing forward and backward citation tracking of related

articles. We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, LISTA, and Google

Scholar using keywords such as “evidence based education,” “evidence based

medical education,” “information service,” and “library service.” Table 1

depicts our search strategy for the PubMed database.

Search Strategy

of PubMed

|

Results |

Search

Strategy |

No. |

|

1,522,557 |

(“Education, medical”[Exp.] OR

teaching[NoExp.] OR education[NoExp.] OR “education, professional”[NoExp.] OR “education, graduate” [NoExp.]

OR “education, continuing” [NoExp.] OR “education,

medical, continuing” [MeSH]) OR (teaching OR

training OR education* OR instruction*) [ti, other

term] |

1 |

|

163,230 |

(“Evidence-based medicine” [Exp.] OR “evidence-based practice”

[NoExp.] OR Evidence-based emergency medicine--education[MeSH] OR

Evidence-based medicine--education[MeSH: NoExp] OR evidence-based practice--education[MeSH:NoExp]) OR “evidence-based”[ti,

ab, other term] |

2 |

|

161,765 |

(“Information services” [NoExp.] OR

“Information storage and retrieval” [NoExp.] OR librarians

[MeSH] OR “libraries, medical” [NoExp.]

OR “libraries, hospital” [MeSH] OR “library

services” [NoExp.]OR“information

dissemination” [MeSH]) OR (librar*

OR information*)[ti, other term] |

3 |

|

1,421 |

1 AND 2 AND 3 |

4 |

|

1,344 |

Limit to:

English language |

5 |

|

721 |

Limit to:

2010/1/1 and 2020/1/2 |

6 |

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

After

implementing search strategies in each database, we excluded non-English

articles, as well as articles focused on evidence based dentistry, nursing, and

pharmacy studies. Because fields like dentistry have unique educational needs

versus medicine, we omitted them from the review. We also excluded study types

such as letters, chapters, book reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, and

viewpoints. We included studies that described an empirical experiment on the

structure and trend of implementing an EBEIS. In this review, it was important

that the information services were not applied in non-educational clinical

settings, nor were proposed templates or opinions. We ended up with 11 articles

published between 2010 and 2020 included in the review. We have described the

process of selecting related studies in Figure 1.

Figure

1

PRISMA

flowchart of study selection (Liberati et al., 2009).

We

compared the bibliographic and introductory data of included studies in Table

2.

Table

2

Introductory

Data of Included Studies

|

Trend of

implementation |

Type of

education |

Setting |

Country |

Year implemented |

Year published |

First author |

|

Searching evidence based information and delivery of documents |

REa |

Morning

report/ rounds/ team conference |

Canada |

2009 |

2011 |

(Aitken et

al., 2011) |

|

Curriculum

architecture-based LibGuides |

UGMEb |

Case-oriented problem solving curriculum |

Canada |

2008-09 |

2011 |

(Neves &

Dooley, 2011) |

|

Learning

package service |

RE |

Morning report |

USA |

2002-10 |

2011 |

(Weaver, 2011) |

|

Consulting,

searching and delivering of information resources |

CPEc |

Morning rounds |

Philippines |

2013 |

2014 |

(Santos & Mariano, 2014) |

|

Searching and

providing evidence for clinical questions |

RE |

Patient rounds |

USA |

2012 |

2014 |

(Yaeger &

Kelly, 2014) |

|

Consult

searching service |

RE |

EBM conference |

USA |

2013-15 |

2015 |

(Zeblisky et al., 2015) |

|

Consulting and

delivery searching service |

CEd |

Patient-family

centered rounds |

USA |

2014-15 |

2017 |

(Herrmann et

al., 2017) |

|

Information

service supporting patient-based scenarios designing/ consulting searching

service |

UGME |

Simulated

patient scenarios |

USA |

2017 |

2018 |

(Blake et al.,

2018) |

|

Consult and

delivery information service |

CE |

Inpatient

rounds |

USA |

2016 |

2018 |

(Brian et al.,

2018) |

|

Consulting and

assisting searching service |

UGME |

Personal

librarian program |

USA |

2013-18 |

2018 |

(Gillum et

al., 2018) |

|

Real-time

clinical searching service |

CE |

Clinical

rounds |

USA |

2014-19 |

2019 |

(Gibbons &

Werner, 2019) |

a Residency

Education, b Under-Graduated Medical Education, c

Continuing Professional Education,

d Clinical

Education

Data Analysis

In

this study, we used a narrative review technique for bringing together findings

of the different studies and accomplishing the review. Narrative analysis with

tabular accompaniment is a typical analysis technique for reviews (Grant &

Booth, 2009). A narrative review synthesizes the available evidence from

different studies to provide a conclusion from collected literature (Green et

al., 2006). For the analysis of included studies, first we read the articles

carefully. Second, we compared the implementation trends of applied information

services in the educational clinical setting and identified the similarities

and differences between structures of implementation trends. Third, we

extracted the related themes for each similar part of the identified structure

through note-taking. Also, we considered the related themes for any differences

between applied information services. Finally, we organized the related themes

of similar parts of implementation trends within the comparison tables.

Results

Implementation

of a program was defined as developing performing procedures for planned tasks

and achieving determined objectives (National

Minority AIDS Council, 2015). In this regard, we tried to

highlight typical characteristics of implementation trends in EBEIS which were

common amongst included studies. After the analysis and comparison of studies,

we recognized five oft-mentioned elements of information services

implementation trends. In addition, for a better understanding of the

implementation process of information services, we summarized the program

development process and practical effects of information services.

Program Development of Information Services

Program

development has a multi-step process. The main elements of the program

development process are required resources for program implementation, program

designing, and predefined measures for determining outputs of the program (National

Minority AIDS Council, 2015). We determined two elements of

program development by comparing the findings of the included studies.

Prerequisites of Programs

One

of the prerequisites of using EBEIS is understanding EBM principles. It is

essential to ask an evidence based question to receive a relevant response from

the information service (Aitken et al.,

2011; Brian et al., 2018). It is

important to have a librarian present at the point of teaching when the cases

are presented. It helps the librarian more quickly and effectively respond to

the learners’ queries (Aitken et al.,

2011; Blake et al., 2018; Gibbons & Werner, 2019; Herrmann et al., 2017; Yaeger

& Kelly, 2014). Other

prerequisites for an effective information service are speed of Internet

connection and access to evidence based databases. Providing appropriate

evidence based information on an educational-clinical question strongly depends

on the accessibility of information sources like databases (Santos &

Mariano, 2014). In this

regard, the availability of infrastructures like a reference-tracker or data

repository which deposits data like educational-clinical questions/answers,

frequency of responded/non-responded questions, and common clinical patient

problems is essential. Deposits of interacted data can be used for subsequent

referencing and establishing a database of evidence based educational

information for high prevalence clinical disorders (Gillum et al.,

2018).

Process of Designing

If

an information service is intended to support the evidence based needs of a

curriculum, the librarian should consider the structure and needed resources of

the curriculum in the design process (Neves &

Dooley, 2011). In this

regard, surveying the information needs of intended users helped to design the

most appropriate services (Zeblisky et

al., 2015). The diversity

of access channels to information services is an essential factor in the design

process. Access via multiple communication channels like email, web, social

networks, or face-to-face communication facilitates the use of information

services for busy clinicians (Brian et al.,

2018).

Implementation Trends of EBEIS

Schedule and Type of Access to Information Services

The

schedule of implementing information services strongly depended on the volume

of assigned tasks that the librarian had to do alongside the duties of

information services. In addition, information services which used

telecommunications channels like phone or email (Brian et al.,

2018; Gillum et al., 2018; Herrmann et al., 2017; Santos & Mariano, 2014; Weaver,

2011) could provide

services during a wider span of time (Table 3).

In

the included studies, information services were implemented in different levels

of medical education from undergraduate to postgraduate degree programs. In

undergraduate medical education, medical students receive the knowledge and

skills needed to be a junior doctor. Then, the junior doctor receives more

training, especially via clinical education, to gain experience, develop skills

for patient care, and prepare for entrance into residency education. This

period is considered the internship. Residency education is a period of

training to educate competent clinicians in a specific medical specialty such

as internal medicine. Internship and residency programs are the two stages of

postgraduate medical education. Clinical education provides an opportunity for

the trainees to acquire practical skills by rotating between clinical

departments of a hospital. Clinical education is an essential part of

postgraduate training (Weggemans et al., 2017; Wijnen-Meijer et al., 2013). In addition, the final stage

of medical education is continuing professional education (CPE), which promotes

lifelong learning for clinicians within their clinical settings. CPE supports

clinical skill development of medical doctors and enhances the outcomes of

patient treatment (Bennett et al., 2000). CPE programs are delivered via

different methods such as rounds, workshops, seminars, conferences, online

learning, telemedicine, and other methods.

Medical

trainees at the undergraduate and graduate levels receive clinical education in

the teaching setting of morning reports and rounds. Morning report is a

case-based meeting where medical students and their educators discuss a

clinical case related to a patient recently admitted to the teaching hospital

(Amin et al., 2000). Rounds or ward rounds are held beside the patient’s bed

and consist of medical educators and students that listen to the patient and

discuss the case of disease presented (O'Hare,

2008).

Table

3

Schedule/Access

to Information Services

|

Setting |

Type of

education |

Schedule of

implementation |

Type of access |

|

Morning

report/ rounds/ team conference (Aitken et

al., 2011) |

REa |

10-12

hours per week |

Face-to-face |

|

Patient

rounds (Yaeger &

Kelly, 2014) |

RE |

Once

per week |

Face-to-face |

|

Morning

rounds (Santos &

Mariano, 2014) |

CPEb |

Every

working days |

Face-to-face/email/

phone |

|

Morning

rounds (Santos &

Mariano, 2014) |

CPE |

24

hours/ all days of week |

Phone/email |

|

Morning

report (Weaver, 2011) |

RE |

5

days a week |

Face-to-face

/ email |

|

EBM

conference (Zeblisky et

al., 2015) |

RE |

Once

per month |

Face-to-face |

|

Patient-family

centered rounds (Herrmann et

al., 2017) |

CEc |

Not

mentioned |

Face-to-face/

email |

|

Clinical

rounds (Gibbons &

Werner, 2019) |

CE |

Once

a week |

Face-to-face |

|

Inpatient

rounds (Brian et al.,

2018) |

CE |

Between

3 to 5 days a week |

Face-to-face/

email |

|

Personal

librarian program (Gillum et

al., 2018) |

UGMEd |

When

the users needed |

Face-to-face/

email |

a

Residency

Education, b Continuing Professional Education, c

Clinical Education, d Under-Graduated Medical Education

Methods of Receiving Educational-Clinical Questions

In

most of the implementation trends for EBEIS, there is a preference for the

presence of a librarian in educational-clinical meetings such as rounds,

morning reports, and EBM conferences (Aitken et al.,

2011; Brian et al., 2018; Gibbons & Werner, 2019; Herrmann et al., 2017;

Santos & Mariano, 2014; Weaver, 2011; Yaeger & Kelly, 2014; Zeblisky et

al., 2015). However, some

of the information services were provided only virtual, with online chatting as

a predefined connection channel between librarians and users. Also, users were

able to submit their feedback on the quality of information services via a text

box on the web (Neves &

Dooley, 2011). Another

channel that was provided for receiving educational-clinical queries was an

online submission form. Receiving queries online made access to information

services easier (Brian et al.,

2018).

Types of Delivery of Information Services

The

most prevalent type of EBEIS was mediated searching and document delivery based

on educational-clinical queries (Aitken et al.,

2011; Brian et al., 2018; Gibbons & Werner, 2019; Herrmann et al., 2017;

Santos & Mariano, 2014; Weaver, 2011; Yaeger & Kelly, 2014), consulting

services for how to formulate a question, and assistance searching the evidence

(Blake et al.,

2018; Gillum et al., 2018; Herrmann et al., 2017; Santos & Mariano, 2014; Zeblisky

et al., 2015). With mediated

searching, the librarian received queries, searched appropriate databases, and

delivered relevant evidence to the student.

Table

4

Evidence

Based Outputs of Information Services

|

Reference

number |

Case

presentation |

Controlled

vocabulary |

Key

words |

Applied

search strategy |

Search

results |

Full-text

of search results |

Abstract

of search results |

Type

of education |

|

(Yaeger &

Kelly, 2014) |

-

a |

+

b |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

Residency

education |

|

(Santos &

Mariano, 2014) |

-

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

Continuing

professional education |

|

(Weaver, 2011) |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

Residency

education |

|

(Herrmann et

al., 2017) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

Clinical

education |

|

(Brian et al.,

2018) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

Clinical

education |

|

(Blake et al.,

2018) |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Under-graduate

medical education |

a not-provided, b

provided

Time of Responding to Queries

The

time that it took a librarian to respond to the educational-clinical questions

influenced the intended learning of trainees. Some of the information services

were designed to provide the needed evidence based information at the

educational session itself or on the same day (Aitken et al.,

2011; Brian et al., 2018; Gibbons & Werner, 2019; Yaeger & Kelly, 2014). In other

studies, the authors did not mention time expectations for receiving answers (Herrmann et

al., 2017; Santos & Mariano, 2014; Weaver, 2011). With

information services that provided online access to questions and answers,

librarians responded to queries in one to three days (Brian et al.,

2018).

Providing Evidence Based Outputs

The

preparation of evidence based outputs for evidence requests is an essential

part of an educational information service. Evidence based output is a document

of what a librarian has done to fulfill an evidence request. The evidence based

output consists of three distinct parts: a) the clinical case presentation of

the patient, b) a record of what keywords and search strategies were used for

retrieving evidence, and c) the retrieved search results, which may include the

abstracts and full text. Each information service examined presented at least

one aspect of the outputs, but a service with all these outputs better supports

the educational needs. The purpose of preparing outputs is to provide a

documented record for what librarians do, thereby helping trainees and

educators learn to better perform their own search for retrieving needed

evidence. Preparing an evidence based output for each request of clinical

evidence is time-consuming for the librarian, but educators and learners then

have the information documented for further learning and later referrals, as

well as evidence based data to deposit in local evidence based databases for

future educational purposes (see Table 4).

Effects on Trainee Learning

In

the field of medical education, EBEIS enhanced learners’ understanding of

evidence based practice in medicine (Blake et al.,

2018; Brian et al., 2018; Yaeger & Kelly, 2014). After learning

about EBM resources (Blake et al.,

2018; Brian et al., 2018; Gibbons & Werner, 2019), the evidence

retrieval behaviour of medical students shifted to more reliable databases for

finding answers to clinical questions (Aitken et al.,

2011). The evidence

based searching skills of learners were strengthened and learners were able to

formulate more meaningful evidence based searches (Brian et al.,

2018; Herrmann et al., 2017; Zeblisky et al., 2015). In addition,

providing such information services meant learners were supplied up-to-date,

high-quality information more quickly (Brian et al.,

2018; Gibbons & Werner, 2019), and enhanced

the learning process (Gibbons &

Werner, 2019). Another

practical effect of EBEIS was saving time for learners in finding

needed evidence (Herrmann et

al., 2017).

Discussion

According

to an analysis of the included studies, EBEIS have been implemented in

different types of teaching-related units (e.g., teaching hospitals), and in

varied target settings (e.g., clinical rounds). In all educational settings,

there is a need for learners to access evidence. EBEIS were flexible in

servicing different needs within their predetermined teaching programs. In this

regard, information services can be implemented in different educational

settings with diverse types of access and schedules of service delivery.

Consequently, changes in curricula and teaching programs that produce new

information needs can be met with reciprocal revisions in the implementation

plan of the information services.

It

is noteworthy that some of the studied information services had unique

procedures in their implementation, which were not executed in the other

information services, and therefore were not categorized into identified

characteristics as a part of this study. Yaeger and Kelly (2014) stated in

their study that a pre-prepared summary of the patient’s clinical situation and

current clinical management was provided for the librarian ahead of clinical

meetings. This procedure helped the librarian to present in the meetings with

more confidence, especially for librarians who are new to delivering EBEIS.

In

some circumstances, the librarian taught the trainees EBM principles and

skills, including understanding and creating PICO questions and designing a

search strategy according to the PICO structure, to help accomplish one of the

prerequisites of using EBEIS (Aitken et al., 2011; Zeblisky

et al., 2015). In this regard, librarians in some of the information services

collaborated with teaching teams to prepare educational materials for trainees.

In such situations, librarians working in the clinical environment could

provide more applicable materials than those excluded from clinical situations

(Blake et al., 2018). In this regard, Safdari et al.

(2018) found the types of educational roles and activities of health care

librarians in teaching information literacy skills and evidence based practice

principles to medical students, educators, and clinicians, especially in the

location of clinics or via online training. Such educational activities

included developing interactive online tutorials, developing video

instructions, and co-teaching in medical faculties. Safadari

et al. identified librarian participation methods in educational programs that

can be considered in the development of EBEIS.

Another

unique procedure which supported student learning was assigning a group of trainees

with a set number to each librarian. The librarian monitored the students’

skill learning according to pre-determined learning objectives, and

reciprocally, each student knew which librarian to contact when they

encountered a learning problem (Gillum et al., 2018).

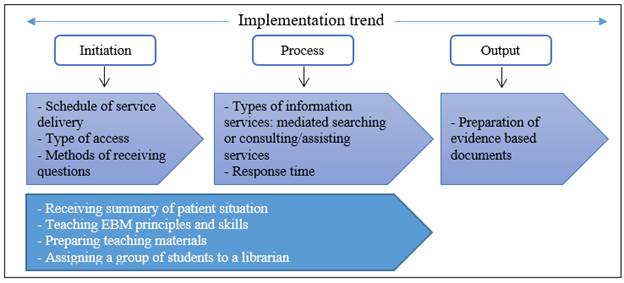

Figure

2 presents a schematic diagram of identified characteristics of information

services within the sequence of program implementation. Also, we included

uncategorized characteristics of information services in the diagram, described in the previous paragraphs.

The

main limitation of this study was differentiating between evidence based

information services which were designed for clinical practice, medical

education, or both simultaneously. In this respect, we tried to include studies

which explained the implementation of an information service for supporting

evidence for any type of educational procedure.

Figure

2

Schematic

diagram of implementation characteristics of information services.

Conclusion

We

conducted this study to identify the structure of the implementation process of

information services which supported evidence based medical education. After

conducting search strategies in target databases and employing

inclusion/exclusion criteria, we selected and analyzed 11 articles. Information

services which were studied in this review supported empirical knowledge for

evidence based medical education at different levels of training and

facilitated evidence based change in educational approaches. The summarized

trend of implementing EBEIS consisted of:

(1)

schedule and type of access;

(2)

methods for receiving questions;

(3)

information service types;

(4)

response time; and

(5)

preparation of evidence based outputs.

On

the basis of the implementation trends of information services being studied,

an applicable EBEIS based on the needs of each educational level can be

designed.

According

to the findings of the current review, we propose the following practical

recommendations. First, a needs assessment of predefined users is a necessary

prerequisite before designing a practical EBEIS. Based on the characteristics

of stakeholders of information services, librarians can benefit from various

needs assessment techniques. The characteristics and needs of stakeholders

should determine the appropriate assessment technique that results in the most

useful data. Second, each educational level needs to have a

specifically-designed information service separately. Third, mediated searching

can be used for undergraduate levels and consulting information services can be

used for graduate or professional levels. Fourth, types of data needed in the

evidence based outputs depend on the needs of intended users. Finally, more

detailed evidence based outputs will fulfill more educational needs in the

future.

It

is also plausible to suggest future studies to compare the structure of

evidence based information services which support clinical practice with

information services that were developed for medical education, in order to

identify additional characteristics of implementation trends of evidence based

information services.

Acknowledgements

This

study is part of a Ph.D. thesis supported by the Iran University of Medical

Sciences under Grant No. IR.IUMS.FMD.REC_1396.9381623003.

Author Contributions

Sedigheh Khani: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology,

Visualization, Writing – original draft Sirous

Panahi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – review

& editing Ali Pirsalehi: Conceptualization,

Writing – review & editing Ata Pourabbasi: Conceptualization,

Writing – review & editing

References

Aitken, E. M.,

Powelson, S. E., Reaume, R. D., & Ghali,

W. A. (2011). Involving clinical librarians at the point of care: Results of a

controlled intervention. Academic

Medicine, 86(12), 1508-1512. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823595cd

Amin, Z.,

Guajardo, J., Wisniewski, W., Bordage, G., Tekian, A., & Niederman, L. G. (2000). Morning report:

Focus and methods over the past three decades. Academic Medicine, 75(10),

S1-5. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200010001-00002

Bennett, N. L.,

Davis, D. A., Easterling, W. E., Friedmann, P., Green, J. S., Koeppen, B. M., Mazmanian, P. E., & Waxman, H. S.

(2000). Continuing medical education: A new vision of the professional

development of physicians. Academic Medicine, 75(12), 1167–1172. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200012000-00007

Blake,

L., Yang, F. M., Brandon, H., Wilson, B., & Page, R. (2018). A clinical

librarian embedded in medical education: Patient-centered encounters for

preclinical medical students. Medical

Reference Services Quarterly, 37(1), 19-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2018.1404384

Brian,

R., Orlov,

N., Werner, D., Martin, S. K., Arora, V. M., & Alkureishi,

M. (2018). Evaluating the impact of clinical librarians on clinical questions

during inpatient rounds. Journal of the

Medical Library Association, 106(2), 175-183. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2018.254

Burns, P.

B., Rohrich, R. J., & Chung, K. C. (2011).

The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine.

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 128(1), 305-310. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e318219c171

Chessare,

J. B. (1996). Evidence-based medical education: The missing variable in the

quality improvement equation. The Joint

Commission Journal on Quality Improvement, 22(4), 289-291. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1070-3241(16)30232-2

Davies,

P. (1999). What is evidence-based education? British Journal of Educational Studies, 47(2), 108-121. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8527.00106

Davies,

S., Herbert, P., Wales, A., Ritchie, K., Wilson, S., Dobie, L., & Thain,

A. (2017). Knowledge into action - Supporting the implementation of evidence

into practice in Scotland. Health

Information and Libraries Journal, 34(1), 74-85. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12159

Djulbegovic,

B., & Guyatt, G. H. (2017). Progress in evidence-based

medicine: A quarter century on. Lancet,

390(10092), 415-423. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31592-6

EBSCO.

(n.d.-a). Information services. In Library, Information Science & Technology

Abstracts Thesaurus. Retrieved March 15, 2021, from http://www.libraryresearch.com/

EBSCO.

(n.d.-b). Information services in education. In Library, Information Science

& Technology Abstracts Thesaurus. Retrieved March 15 2021, from http://www.libraryresearch.com/

Emami,

S. A. H., Khankeh, H., Karbasi

Motlagh, M., Zarghi, N.,

& Shirazi, M. (2019). Exploring experience of Iranian medical sciences

educators about Best Evidence Medical Education: A content analysis. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 8,

247-252. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_428_19

Fennessy,

G. (2001). Knowledge management in evidence-based healthcare: Issues raised

when specialist information services search for the evidence. Health Informatics Journal, 7(1), 4-7. https://doi.org/10.1177/146045820100700102

Gibbons,

P., & Werner, D. A. (2019). Embedded clinical librarianship: Bringing

medical reference services bedside. Public

Services Quarterly, 15(2), 169-175. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228959.2019.1583153

Gillum,

S., Williams, N., Herring, P., Walton, D., & Dexter, N. (2018). Encouraging

engagement with students and integrating librarians into the curriculum through

a personal librarian program. Medical

Reference Services Quarterly, 37(3), 266-275. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2018.1477710

Grant,

M. J., & Booth A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review

types and associated methodologies. Health

Information and Libraries Journal, 26, 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Green,

B. N., Johnson, C. D., & Adams A. (2006). Writing narrative literature

reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. Journal of

Chiropractic Medicine, 5(3), 101-117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6

Guyatt,

G., Cairns, J., Churchill, D., Cook, D., Haynes, B., Hirsh, J., Irvine, J.,

Levine, M., Levine, M., Nishikawa, J., Sackett, D., Brill-Edwards, P.,

Gerstein, H., Gibson, J., Jaeschke, R., Kerigan, A., Neville, A., Panju,

A., Detsky, A., … Enkin, M.

(1992). Evidence-based medicine: A new approach to teaching the practice of

medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association, 268(17),

2420-2425. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03490170092032

Haig,

A., & Dozier, M. (2003a). BEME Guide No 3: Systematic searching for

evidence in medical education—Pt. 1: Sources of information. Medical Teacher, 25(4), 352-363. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159031000136815

Haig,

A., & Dozier, M. (2003b). BEME Guide No. 3: Systematic searching for

evidence in medical education—Pt. 2: Constructing searches. Medical Teacher, 25(5), 463-484. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590310001608667

Harden,

R. M., Grant, J., Buckley, G., & Hart, I. R. (2000). Best evidence medical

education. Advances in Health Sciences

Education: Theory and Practice, 5(1), 71-90. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1009896431203

Hart,

I. R., & Harden, R. M. (2000). Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME): A

plan for action. Medical Teacher, 22(2),

131-135. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590078535

Herrmann,

L. E., Winer, J. C., Kern, J., Keller, S., & Pavuluri,

P. (2017). Integrating a clinical librarian to increase trainee application of

evidence-based medicine on patient family-centered rounds. Academic Pediatrics, 17(3), 339-341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.11.005

Holland,

J., & Haynes, R. B. (2005). McMaster

Premium Literature Service (PLUS): An evidence-based medicine information

service delivered on the Web. AMIA ... Annual Symposium proceedings /

AMIA Symposium, 2005, 340-344. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1560593

Jordan,

Z., & Porritt, K. (2004). Evidence-based health information provision:

Development of an online consumer 'request for information' service. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 1(4),

237-240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04065.x

Liberati,

A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., AIoannidis, J.

P., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., &

Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and

meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation

and elaboration. British Medical Journal, 339, b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700

McGowan,

J., Hogg, W., Rader, T., Salzwedel,

D., Worster, D., Cogo, E.,

& Rowan, M. (2010). A rapid evidence-based service by librarians provided

information to answer primary care clinical questions. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 27(1), 11-21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00861.x

National

Minority AIDS Council. (2015). Program

development. http://www.nmac.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Program-Development.pdf

Neves,

K., & Dooley, S. J. (2011). Using LibGuides to offer library service to

undergraduate medical students based on the case-oriented problem solving

curriculum model. Journal of the Medical

Library Association, 99(1), 94-97. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.99.1.017

O'Hare, J. A.

(2008). Anatomy of the ward round. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 19(5),

309-313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2007.09.016

Onyura,

B., Légaré, F., Baker, L., Reeves, S., Rosenfield,

J., Kitto, S., Hodges B., Silver I., Curran V., Armson H., & Leslie, K. (2015). Affordances of

knowledge translation in medical education: A qualitative exploration of empirical

knowledge use among medical educators. Academic

Medicine, 90(4), 518-524. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000590

Poirier,

T., & Behnen,

E. (2014). Where and how to search for evidence in the education literature:

The WHEEL. American Journal of

Pharmaceutical Education, 78(4), 70-77. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe78470

Reed,

D., Price, E. G., Windish,

D. M., Wright, S. M., Gozu, A., Hsu, E. B., Beach M.

C., Kern D., & Bass, E. B. (2005). Challenges in systematic reviews of

educational intervention studies. Annals

of Internal Medicine, 142(12 Pt. 2), 1080-1089. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-142-12_part_2-200506211-00008

Sackett, D. L.,

Rosenberg, W. M., Gray, J. A., Haynes, R. B. & Richardson, W. S. (1996).

Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn't. British Medical

Journal, 312(7023), 71-72. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71

Safdari, R., Ehtesham, H., & Bahadori, L.

(2018). Highlighting a valuable dimension in health care librarianship: A

systematic review. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 32,

1-7. https://doi.org/10.14196/mjiri.32.42

Sandars,

J., & Patel, R. (2015). It's OK for you but maybe not for me: The challenge

of putting medical education research findings and evidence into practice. Education for Primary Care, 26(5),

289-292. https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2015.1079008

Santos,

M. A. A., & Mariano, G. S. L. (2014). Information professional at the point

of care: Clinical librarian service in neurocritical care. Journal of Philippine Librarianship, 34, 61-69. https://journals.upd.edu.ph/index.php/jpl/article/view/4585

Shortell,

S. M., Rundall, T. G., & Hsu, J. (2007).

Improving patient care by linking evidence-based medicine and evidence-based

management. JAMA, 298(6), 673-676. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.6.673

Sur,

R. L., & Dahm,

P. (2011). History of evidence-based medicine. Indian Journal of Urology: IJU: Journal of the Urological Society of

India, 27(4), 487-489. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-1591.91438

Suttle,

C. M., Challinor,

K. L., Thompson, R. E., Pesudovs, K., Togher, L., Chiavaroli, N., Lee

A., Junghans B., Stapleton F., Watt K., & Jalbert, I. (2015). Attitudes and barriers to

evidence-based practice in optometry educators. Optometry and Vision Science, 92(4), 514-523. https://doi.org/10.1097/opx.0000000000000550

Thomas,

A., Gruppen, L. D., Vleuten, C. V. D., Chilingaryan,

G., Amari, F., & Steinert, Y. (2019). Use of evidence in health professions

education: Attitudes, practices, barriers and supports. Medical Teacher, 41(9), 1012-1022. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2019.1605161

Weaver,

D. (2011). Enhancing resident morning report with “Daily Learning Packages”. Medical Reference Services Quarterly, 30(4),

402-410. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2011.609077

Weggemans, M. M., Dijk,

B, V., Dooijeweert, B. V., Veenendaal,

A. G., & Cate, O. T. (2017). The postgraduate medical education pathway: An

international comparison. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 34(5),

1-16. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma001140

Wijnen-Meijer, M., Burdick,

W., Alofs, L., Burgers, C., & Cate, O. T. (2013). Stages and transitions in

medical education around the world: Clarifying structures and

terminology. Medical Teacher, 35(4), 301-307. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2012.746449

Yaeger,

L. H., & Kelly, B. (2014). Evidence-based medicine: Medical librarians

providing evidence at the point of care. Missouri

Medicine, 111(5), 413-415. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6172079

Zeblisky,

K., Birr, R. A., & Guerrero, A. M. S. (2015). Effecting change in an

evidence-based medicine curriculum: Librarians' role in a pediatric residency

program. Medical Reference Services

Quarterly, 34(3), 370-381. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2015.1052702