Research Article

Advancing the Reference Narrative: Assessing Student

Learning in Research Consultations

Doreen R. Bradley

Director of Learning

Programs and Initiatives

University of Michigan

Library

Ann Arbor, Michigan, United

States of America

Email: dbradley@umich.edu

Angie Oehrli

Learning Librarian

University of Michigan

Library

Ann Arbor, Michigan, United

States of America

Email: jooerhli@umich.edu

Soo Young Rieh

Professor and Associate Dean

for Education

School of Information,

University of Texas at Austin

Austin, Texas, United States

of America

Email: rieh@ischool.utexas.edu

Elizabeth Hanley

Post Graduate Fellow

Academic Innovation,

University of Michigan

Ann Arbor, Michigan, United

States of America

Email: hanleyel@umich.edu

Brian S. Matzke

Digital Humanities Librarian

Central Connecticut State

University Library

New Britain, Connecticut,

United States of America

Email: bmatzke@ccsu.edu

Received: 30 Aug. 2019 Accepted: 9 Jan. 2020

![]() 2020 Bradley, Oehrli, Rieh, Hanley, and Matzke. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Bradley, Oehrli, Rieh, Hanley, and Matzke. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29634

Abstract

Objective – As reference services continue to

evolve, libraries must make evidence based decisions

about their services. This study seeks to determine the value of reference

services in relation to student learning acquired during research

consultations, by soliciting students’ and librarians’ perceptions of

consultation success and examining the degree of alignment between them.

Methods

–

The alignment of students’ learning outcomes (reported skills and knowledge

acquired) with librarians’ expectations for student learning during

consultations was assessed. An online questionnaire was conducted to gather

responses from students who had sought consultation services; 20 students

participated. In-person interviews took place with eight librarians who had

provided these consultations. The online questionnaire for students included

questions about students’ assessments of their self-identified learning goals

through consultation with a librarian and their success at applying the

knowledge and skills gained. Librarian interviews elicited responses about

students’ prior research experience, librarians’ objectives for student

learning, librarians’ perceptions of student learning outcomes, and perceived

consultation success. The responses of both the students and the librarians

were coded, matched, and compared.

Results –

Students and librarians both considered the consultation process to be

successful in advancing learning objectives and research skills. All students

reported that the consultations met their expectations, and most reported that

the skills acquired were applicable to their projects and significantly

improved the quality of their work. Librarians expressed confidence that

students had gained competency in the following skill sets: finding sources,

search strategy development, topic exploration, specific tool use, and library

organization and access. A high degree of alignment was observed in the

identification by both students and librarians of “finding sources” as the

skill set most in need of enhancement or assistance, while some disparity was

noted in the ranking of “search strategy development,” which librarians ranked

second and students ranked last.

Conclusion

–

The data demonstrate that both students and librarians perceived individual

research consultations as an effective means to meet student learning

expectations. Study findings suggest that as reference models continue to

change and reference desk usage declines, research consultations remain a

valuable element in a library’s service model and an efficient use of human

resources.

Introduction

Librarians are increasingly expected to demonstrate the value of their

services for improving student learning and success, and to make informed

decisions based on empirical data. While research consultation services have

been shown to be useful for students (Butler & Byrd, 2016), and although

users report satisfaction with such services (Ishaq

& Cornick, 1978; Magi & Mardeusz, 2013;

Martin & Park, 2010; Rogers & Carrier, 2017), most previous studies

evaluating research consultation services have tended to focus on the usage or

effectiveness of the service (e.g., Attebury,

Sprague, & Young, 2009; Watts & Mahfood,

2015). We still know little about the extent to which these services affect

student learning in academic library settings specifically and in higher

education more generally.

Our study investigated the value and contributions of research

consultation services with respect to student-centered learning objectives. We

sought to understand students’ experience beyond the use of the service or the

evaluation of the quality of the service. Therefore, we conducted an empirical

study to examine the value of research consultation services to assess student

learning and the direct implications of that learning for student success.

This study was conducted in a U.S. research university with 45,000

students, comprising 30,000 undergraduates and 15,000 graduate students. The

University’s library offers various consultation services through which

students can meet one-on-one with a librarian for approximately 30 minutes.

While the library provides specialist consultation services whereby users can

receive assistance from an expert in an academic discipline or technological

field, the library also offers a general research consultation service staffed

by librarians identified as generalists who have some knowledge in many fields.

This study focuses on the consultations provided through this general service.

Consultation topics are patron driven, typically centering on questions

that students have about research-based academic projects. The consultation

format is flexible, determined by students’ self-identified learning

objectives. With the purpose of evaluating the extent to which students

perceived their learning objectives had been achieved and to better understand

the students’ self-identified learning objectives, an online questionnaire was

initiated by contacting those students who had used the consultation service.

To obtain librarians’ perceptions of those same consultations, all of the

librarians who had provided the service to those students who responded to the

online questionnaire were interviewed. This method enabled examination of the

alignment between students’ reported acquisition of knowledge and skills and

the librarians’ expectations and perceptions of student learning during the

consultation process.

Literature Review

The literature on library research consultations dates back to the

1970s, when academic libraries began to offer appointment-based consultation

services. In their early study of consultations at the University of North

Carolina at Chapel Hill, Ishaq and Cornick (1978)

found high degrees of satisfaction with the program; all of the 49

questionnaire respondents who had utilized the service indicated that they

would use the service again and recommend it to others. Later studies found

similarly high levels of satisfaction with library consultation services at

other institutions. For example, a study of the University of Idaho’s library

research consultations found that an average of 115 students per year utilized

the service, a number that remained relatively stable over the 10-year study

period and that represented a wide array of departments and levels of study (Attebury et al., 2009). In addition, in a recent

questionnaire of 80 students, 86% described their consultations as “very

useful” and 14% described them as “somewhat useful” (Butler & Byrd, 2016,

p. 85).

Much of the recent literature on consultation services focuses on the

role of technology in facilitating research consultations. Online appointment

tools like Google Calendar and YouCanBook.me have been found to decrease

student wait times and mitigate library anxiety by enabling students to make

appointments without having to contact a librarian directly (Cole & Reiter,

2017; Kuglitsch, Tingle, & Watkins, 2017). At the

same time, employing online note-taking tools like Evernote during

consultations has been found to help students organize information and provide

a research narrative that students can refer back to (Kani,

2017).

Despite the usefulness of digital tools in

consultation sessions, many students describe face-to-face consultations as the

easiest and most efficient method for getting help, in comparison to forms of

virtual reference such as chat (Magi & Mardeusz,

2013). For example, when working in collaboration with their university writing

center, Meyer, Forbes, and Bowers (2010) described the importance of providing

a dedicated, highly visible space for research consultations; having a physical

space that served as the “research center” eased students’ anxiety about asking

for help and facilitated the promotion of the library’s research services.

Similarly, Rogers and Carrier (2017) found that students appreciated the

opportunity to meet in a private consultation environment as opposed to the

“open” environment of the reference desk.

Many research consultation studies center

on specific student populations or circumstances. For example, Isbell (2009)

focused on honors students’ perceptions of a consultation service because such

students are highly motivated, study a wide range of disciplines, and tend to

overestimate their research abilities. Faix,

MacDonald, and Taxakis (2014) surveyed students from

both a senior capstone class and a freshman seminar who were required to attend

a library research consultation. The study found that upper-level students

benefited more from the consultations than freshmen, who were sometimes

overwhelmed by the number of resources that consultation sessions helped them

locate. In addition, Kolendo (2016) identified the

extra-credit consultation as a unique circumstance, in which students schedule

sessions for the credit only, usually after having already completed their

papers.

A persistent challenge is measuring the effectiveness of research

consultations. Fournier and Sikora (2015, 2017) discussed the lack of

assessment in scholarly literature, finding that most libraries either practice

no form of assessment or rely solely on informal feedback from users. However,

the literature demonstrates that more sophisticated analyses have been

attempted. Sikora, Fournier, and Rebner (2019)

administered pre- and post-consultation tests, demonstrating statistically

significant improvements in students’ search abilities and confidence in their

research skills after consultations. Reinsfelder

(2012) used citation analysis to show that consultations positively impacted

the quality and quantity of sources that students used in their papers.

In addition to quantitative metrics, qualitative research methods such

as questionnaires (Butler & Byrd, 2016), interviews (Rogers & Carrier,

2017), focus groups (Watts & Mahfood, 2015), and

analyses of librarians’ consultation notes (Suarez, 2013) provide valuable

insights into what students learn during consultation sessions. Studies have

found that confusion about library terminology can impede student learning

(Butler & Byrd, 2016), but that students value the individualized attention

from in-depth engagement with the librarian, as well as the librarians’ perceived

subject expertise (Rogers & Carrier, 2017). Relatedly, students who

participate in consultations have reported a higher degree of confidence in

their research abilities, believing that their research has become more

efficient and feeling that they have developed good relationships with the

librarian as an educator (Watts & Mahfood, 2015).

However, others have found that students tend to overestimate their

information-seeking abilities even when they still struggle to develop search

strategies or generate keywords beyond those that are laid out in the

assignment prompt (Suarez, 2013). In this manner, students in research

consultations appear to evince the Dunning-Kruger effect, the cognitive bias

whereby people are unable to recognize their own incompetence (Suarez, 2013).

On the other hand, librarians have sometimes been found to underestimate the

effectiveness of the consultation, a phenomenon known as provider pessimism

(Butler & Byrd, 2016).

Aims

This study therefore aims to contribute to this growing body of

literature on student learning through research consultations, by providing a more complete and nuanced picture of students’ and

librarians’ perceptions of the consultation process. Specifically, three

research questions are addressed:

1.

How do students who participated in a library

consultation perceive their learning objectives and experience?

2.

How do librarians who provided a library consultation

conceptualize the student learning from this service?

3.

How aligned are students and librarians in their perceptions

of the degree of success of the consultation?

Methods

Study data was collected using a student questionnaire

and in-person interviews with librarians. First, a questionnaire was sent to

students who had participated in consultations during the Fall 2017 and Winter

2018 semesters. The questionnaire had three main foci: (1) understanding

students’ self-identified learning objectives; (2) evaluating the degree to

which students perceived that these learning objectives were achieved; and (3)

understanding students’ perceptions of how they applied the knowledge and

skills acquired in the consultations to their course projects. After the

student questionnaires were completed, the librarians were interviewed. In

order to minimize potential biases, neither the students nor the librarians

were informed about the study prior to the consultations.

Part 1: Student Perspectives

Participants

During the Winter 2018 semester, questionnaires were sent to the 38

students who had participated in research consultations during the Fall 2017 or

Winter 2018 semesters (see Appendix A). Of those 38, 20 questionnaires were

completed for a 53% response rate. Researchers administered the questionnaire

several months after the consultations occurred in order to permit students

sufficient time to complete projects, to receive feedback on their projects,

and to reflect upon their learning. Students required approximately 30 minutes

to complete the questionnaire. A $30 Amazon gift card was offered as an

incentive to increase the response rate and to motivate students to provide

thoughtful and accurate responses.

Measures

The questionnaire was distributed via email using

Qualtrics software and was comprised of 31 items in total, although not all

questions were visible to all students due to the use of skip logic. In

addition to demographic questions there were open-ended items asking about the

students’ self-identified learning objectives (“What did you hope to learn from

the consultation?”) and student perceptions of the learning that took place

(“What, if anything, did you discuss that was new to you?”). Closed-ended items

asked about student perceptions of the success of the consultations (“Do you

feel that the consultation met your expectations?” “To what extent did this service

improve the quality of your project/assignment?”). We also asked for specific

feedback that students may have received from course instructors on their

projects. Although student emails were solicited in the questionnaire for

possible future contact, follow-up interviews were not conducted.

Student learning objectives and student perceptions of

learning were coded using four categories as follows:

1.

Library tools (use of research tools such as specific

databases)

2.

Library organization and access (understanding how to

access print and digital resources within the library, including the physical

library buildings and library website)

3.

Research process (topic exploration, search strategy

development, and finding, evaluating, and citing sources)

4.

Other (goals not covered above, such as earning extra

credit for meeting with a librarian)

Student perceptions of success were coded along two dimensions using a

four-point Likert scale:

1.

Success, ranging from one (not at all) to four

(significantly)

2.

Met expectations, ranging from one (not at all) to

four (significantly)

After the questionnaire closed, the responses were downloaded from

Qualtrics in CSV format. Two researchers then coded the open-ended responses

using NVivo software.

Part 2: Librarian Perspectives

Participants

After students submitted their questionnaires, the

librarians who had conducted the consultations were contacted for interviews.

We sought to understand what the librarians believed the students had needed to

learn in order to complete their projects and to compare this to the students’

own perceptions of what they themselves needed to learn. Therefore, the

interviews focused on (1) understanding librarians’ perceptions of student

learning needs and (2) evaluating the degree to which librarians believed these

learning needs were achieved.

Using consultation scheduling software, we identified

the names of eight librarians who provided the consultations for all 20

students were identified using consultation scheduling software. One of the

eight librarians provided approximately half of the consultations, while each

of the other librarians conducted between one and three consultations. All

eight librarians were interviewed during the Winter 2018 semester. Student and

librarian responses were matched based on library records of the research

consultations. Interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes and were audio

recorded and transcribed for coding purposes.

Measures

To assess librarians’ perspectives of student learning, an interview

protocol was developed that contained questions about the students’ prior

research experience (“What was your impression of the student’s research skills

at the start of the session?”); librarian learning objectives (“What goals did

you have for the session? That is, what did you want the students to walk away

from the session having learned?”); librarian perceptions of student learning

outcomes (“What [skills and concepts] did the student learn?”); and

consultation success (“On a scale of one to ten, ten being highly successful,

one being not successful, how successful was the session?”) (see Appendix B).

The interview questions were coded along the same four dimensions outlined for

student learning objectives and student perceptions of learning: library tools,

library organization and access, research process, and other. The question

about consultation success asked librarians to provide a rating on a scale from

1 (very unsuccessful) to 10 (very successful). The transcribed interviews were

coded by two researchers using NVivo software. A codebook was developed

focusing on the following themes: library organization and access, specific

tools, and the research process. We test coded five interviews to assess the

feasibility of the coding scheme, to facilitate consensus on the application of

the codes, and to ensure inter-coder reliability.

Demographic Background and

Consultation Length

Of the 20 students who had received consultations, 16 were undergraduate

students, one was a master’s student, one was a PhD student, and two students

self-identified as “other.” The students represented a total of 14 disciplines

including nursing, economics, social work, political science, history, computer

science, international studies, kinesiology, biochemistry, and several other

disciplines that included five students with undeclared majors. The duration of

the consultations varied; four consultations lasted over 30 minutes, nine were

20–30 minutes long, six were 10–20 minutes long, and one lasted less than 10

minutes. The majority, 15 of the sessions, were in the 10–30

minute range. All of the students responded that they were working on a

project; of these, 15 projects were for a course and five were not course

related. All consultations were sought to meet immediate, short-term objectives

rather than for longer-term projects. The eight librarians had between two and

30 years of reference service experience in academic libraries.

Eighteen students reported that they remembered the consultation “well,”

while only two reported remembering it “a little.” Therefore, although students completed the

questionnaire several months after the consultations occurred, they were able

to provide a good level of detail in their responses. Likewise, for the

librarians, most remembered the consultations well with some having sent

follow-up email messages to students. In one case, a librarian was not able to

recall enough information about the consultation to assess its level of

success.

Results

In this section, we examine the results of our study from two

perspectives: student perceptions about their own learning and their

assessments of the success of the consultations versus librarian perspectives

on student learning and consultation success.

Student Learning: Student Perspectives

In general, students reported that their self-identified learning

objectives were met during the consultations, responding consistently that the

consultations had helped them to learn new skills for their projects; the fact

that the consultations provided them with search tactics that they could use in

the future was appreciated. The students also reported that the consultations

had helped them to locate higher quality sources. One respondent wrote, “I was

completely lost on where to go. The topic was a little bit peculiar and doing a

simple Google search was not helping much. The consultation helped me gain more

trustworthy sources, which was key.” There were no discernible differences

between undergraduate and graduate student participants’ expectations or

perceptions about consultation outcomes.

Students identified their top four learning objectives as (1) finding

sources (n = 19); (2) using specific

tools/databases (n = 10); (3) library

organization and access, which included navigating both the physical space of

the library and the library website (n

= 7); and (4) search strategy development (n

= 3).

One interesting finding is that students reported that they applied what

they had learned to their projects. Sharing feedback received from their course

instructors, respondents stated: “My instructor said my sources were extremely

strong and made my argument more well-rounded”; “my compilation of data was

outstanding and everything they were looking for”; and “I got good feedback and

a good grade in part because of the thoroughness to which I worked to find

meaningful resources.”

One of the questions we asked in the questionnaire was whether students

had used skills learned during the consultations to enhance their work on any

subsequent projects, as this would demonstrate transferable skills learned.

Half of the survey respondents (n =

10), indicated that they were able to apply something they discussed during the

consultations to a project other than the one that led them to schedule the

consultation. One student commented, “I have since used the methods [the

librarian] taught me to aid my research in my new political science research

assistant job. I have also used them in other courses for other essays and

projects.” Another offered, “I’m working on a psych project now that I

regularly use my database research skills to find articles for.”

Some students reported that they shared what they learned from the

consultation service with others, such as one respondent who indicated, “I was

able to teach these techniques to my research partner to find other sources for

our project.” Such responses strongly suggest that student-librarian

consultations pay themselves forward by helping students to use their enhanced

skills and knowledge in subsequent research projects, and by enabling students

to teach these skills to others, which extends the impact of consultations

beyond a single-project application.

Student Learning: Librarian Perspectives

At the beginning of each interview, we asked

librarians to rate each student’s pre-consultation level of research

experience. Most students (n = 12)

were rated “low” in previous research experience, while only two students were

identified as having “high” skill levels. Data analysis revealed that the

librarians identified four main skill sets that students needed to acquire or

enhance in order to successfully complete work on their projects, with

individual students requiring help in several of these skill areas: (1) finding

sources (n = 19); search strategy

development (n = 15); (3) topic

exploration (n = 5); and (4) using

specific tools (n = 3).

Librarians described in detail how they felt that

students displayed their understanding of the concepts covered in the

consultation, describing how students suggested synonyms to create better

search strategies and used new search strategies and new databases while

searching alongside the librarian. While librarians recognized that the

students had requested help with specific databases, they felt that students

would benefit from more broad-based help, for example, with formulating search

strategies or exploring topics through using filters to refine search results.

Librarians expressed confidence that the students had gained competency in the

top learning needs that they had identified (Table 1).

Table

1

Librarian

and Student Assessment of the Top Four Student Learning Needs

|

Librarian

Perceptions |

Student

Perceptions |

|

1. Finding sources |

1. Finding sources |

|

2. Search strategy development |

2. Using specific tools/databases |

|

3. Topic exploration |

3. Library organization and access |

|

4. Using specific tools |

4. Search strategy development |

Consultation Success: Student and Librarian Perspectives

Using a scale of significantly,

somewhat, a little, and not at all,

all 20 students reported that the consultations had met their expectations,

with 15 rating that their expectations had been significantly met and five rating that their expectations had been somewhat met. No students reported that

the consultation met their expectations a

little or not at all. Using a

similar scale to assess whether the consultations had any impact on the

participants’ projects, 19 students out of 20 felt that the consultations

improved their project to some degree. Fourteen students responded that the

consultations improved their projects significantly,

three somewhat, and two a little.

Only one reported that the consultation did not improve their project at all;

this student had already explored a significant amount of resources and was

referred to a subject specialist outside of the general reference consultation

service.

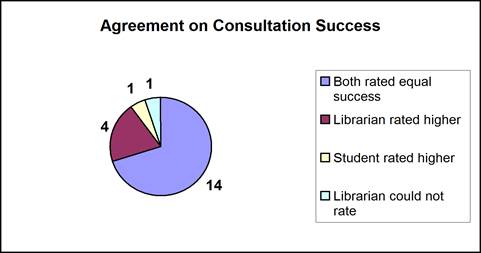

![]()

Figure

1

Agreement

on consultation success between librarians and students.

Librarians’ assessments of the success of consultations were similar to

those of the students. Using a scale of 1–10, ranging from 1 (very unsuccessful) to 10 (very successful), librarians reported

that they felt 13 of the consultations were very

successful (rated 8–10), and that six were somewhat successful (rated 4–7). None of the librarians considered

any consultations to be very unsuccessful

(rated 1–3), although one librarian revealed that they could not remember

enough details to rate the success of one consultation.

The rates at which the librarians and students agreed on the degree of

success were measured using the same scale as above. For 14 consultations, both

groups agreed on the level of success. Of interest, the librarians rated four

consultations as having been more successful than the students rated those

consultations. Although, one student did rate a consultation as more successful

than the librarian did. For the instance in which the librarian could not

remember enough about the consultation to attach a level of success, we decided

not to compare it with the student-reported level of success (Figure 1).

Discussion

This study was designed to address three questions: how did students who

accessed the library consultation service perceive their learning objectives

and experience? How did librarians who provided the library consultation

service conceptualize the student learning from this service? How aligned were

students and librarians in their perceptions of the degree of success of the

consultations?

With regard to learning objectives, there was almost complete agreement

(19 cases) between both librarians and students that “finding sources” was the

most important area requiring new and additional skills in a general

consultation. However, both groups diverged when ranking the other learning

objectives (see Table 1).

Perhaps most striking is the discrepancy in the ranking of “search

strategy development,” which was ranked second in importance by librarians but

last by students, whereas “specific tools and databases” was ranked second in

importance by students and last by librarians. “Topic exploration” was third in

importance for the librarians, but was not named among the top four learning

needs by students. “Library organization and access,” named third in importance

by students, was not mentioned by librarians among their top four.

When describing gaps in students’ skill sets, the librarians were more

likely to discuss broader concepts such as critical thinking, as well as

universally applicable competencies like search strategy development and topic

exploration. By contrast, students tended to discuss basic needs with concrete

outcomes, wanting to learn how to use a particular tool or to find a specific

source at the library. This discrepancy is an opportunity for librarians to

expand students’ awareness of their own learning needs and to encourage

self-reflection.

Some research suggests that while students report a higher degree of

confidence in their research abilities after a consultation (Watts & Mahfood, 2015), they may overestimate their

information-seeking abilities overall (Suarez, 2013). A higher degree of

confidence after a consultation may be an indicator of student success for the

consultation. Librarians have underestimated their effectiveness in

consultations in general (Butler & Byrd, 2016), and it might be concluded

that librarians should be more confident than they are about the impact of

their work. These prior studies indicate that there is a possible mismatch

between what students rate as successful and what librarians perceive as

impactful. The findings of this study also show that students and librarians

interpret the success of research consultations in slightly different ways.

While most of the librarians and students agreed on the level of success of the

consultations in this study, in four instances the librarians rated the

consultations as more successful than did the students involved in those

consultations, a finding that is seemingly inconsistent with Butler and Byrd’s

(2016) work. There was only one case in which the student’s rating of the

consultation’s success was higher than the librarian’s.

While the discrepancy in perceptions of success among these five cases is

interesting, more noteworthy is the fact that some degree of success was

indicated by both librarians and students in all cases. We interpret this

finding as suggesting the potential benefit of incorporating two routine

practices into the consultation process: having students and librarians

identify clear learning objectives at the outset of the consultation; and

following up consultations by asking students about their level of satisfaction

with the process and their success at applying newly developed library skills

to additional projects. We believe that these practices are likely to improve

student-librarian consensus of perceived success, enhance communication between

students and librarians, and provide feedback to aid the ongoing improvement of

consultation services.

By a very large measure, both librarians and students felt that the time

and effort put forth in the consultations was worthwhile. Nearly all students,

19 out of 20, reported that the consultations improved their projects to some

degree, while all responded that the consultations met their expectations.

Consistent with Butler and Byrd’s (2016) work, the librarians reported feeling

that slightly fewer of the consultations (17 out of 20) were very successful.

However, when assessing how well the self-identified learning objectives were

met during the consultations, the data illustrate that half of the student

respondents were able to apply something that they had discussed during the

consultations to projects other than the one for which they had scheduled the

consultation. This finding indicates the acquisition of transferable skills and

demonstrates both the short- and long-term value of consultations for improving

students’ research skills.

The consultations in this study were initiated for

immediate, short-term needs associated with required projects, rather than for

self-directed, longer-term projects. A valuable extension of this study might

include consultations with undergraduates who are completing long-term

projects, such as honor theses, or consultations with a sampling of graduate

students. While the learning objectives in these cases might differ from those

in the present study, the measures of perceived consultation success

(applicability of new or improved skills, transferability of skills to other

contexts, and alignment between librarian and student perceptions of success)

would still pertain, thus offering a more complete picture of student learning

through consultations.

Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to assess student

learning from research consultations in the academic library by identifying the

students’ own learning goals and measuring the success in achieving those goals

in relationship to librarian perceptions of the work completed in those

consultations. Students and librarians in this study had the same primary goal

in these consultations: to find sources for a research project. Though there

were some differences in perceptions of learning outcomes outside of that

primary goal, in most cases, both students and librarians interpreted the

degree of success in the consultation similarly. The findings clearly

demonstrate that individual research consultations are effective and impactful

in meeting student learning needs. As reference models continue to change and

reference desk usage declines, general research consultations are a valuable

element in librarians’ service model and an efficient use of human resources.

References

Attebury, R., Sprague,

N., & Young, N. J. (2009). A decade of personalized research assistance. Reference Services Review, 37(2), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907320910957233

Butler, K., & Byrd, J. (2016). Research

consultation assessment: Perceptions of students and librarians. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(1), 83–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2015.10.011

Cole, C., & Reiter, L. (2017). Online

appointment-scheduling for optimizing a high volume of research consultations. Pennsylvania Libraries: Research &

Practice, 5(2), 138–143. https://doi.org/10.5195/palrap.2017.155

Faix, A., MacDonald,

A., & Taxakis, B. (2014). Research consultation

effectiveness for freshman and senior undergraduate students. Reference Services Review, 42(1), 4–15.

https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-05-2013-0024

Fournier, K., & Sikora, L. (2015). Individualized

research consultations in academic libraries: A scoping review of practice and

evaluation methods. Evidence Based

Library & Information Practice, 10(4),

247–267.

https://doi.org/10.18438/B8ZC7W

Fournier, K., & Sikora, L. (2017). How Canadian librarians practice and assess individualized research

consultations in academic libraries: A nationwide survey. Performance Measurement and Metrics, 18(2), 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1108/PMM-05-2017-0022

Isbell, D. (2009). A librarian research consultation

requirement for university honors students beginning their theses. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 16(1), 53–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691310902754072

Ishaq, M. R., &

Cornick, D. P. (1978). Library and research consultations (LaRC):

A service for graduate students. RQ, 18(2), 168–176. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/25826127

Kani, J. (2017).

Evernote in the research consultation: A feasibility study. Reference Services Review, 45(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-05-2016-0034

Kolendo, J. (2016). The

extra credit consultation in two academic settings. The Reference Librarian, 57(3),

247–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2016.1129246

Kuglitsch, R. Z., Tingle,

N., & Watkins, A. (2017). Facilitating research consultations using cloud

services: Experiences, preferences, and best practices. Information Technology and Libraries, 36(1), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.6017/ital.v36i1.8923

Magi, T. J., & Mardeusz,

P. E. (2013). Why some students continue to value individual, face-to-face

research consultations in a technology-rich world. College & Research Libraries, 74(6), 605–618. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl12-363

Martin, P. N., & Park, L. (2010). Reference desk

consultation assignment: An exploratory study of students’ perceptions of

reference service. Reference & User

Services Quarterly, 49(4),

333–340. https://doi.org/10.5860/rusq.49n4.333

Meyer, E., Forbes, C., & Bowers, J. (2010). The

research center: Creating an environment for interactive research

consultations. Reference Services Review,

38(1), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321011020725

Reinsfelder, T. L. (2012).

Citation analysis as a tool to measure the impact of individual research

consultations. College & Research

Libraries, 73(3), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl-261

Rogers, E., & Carrier, H. S. (2017). A qualitative

investigation of patrons’ experiences with academic library research

consultations. Reference Services Review,

45(1), 18-37.

https://doi.org/10.1108/RSR-04-2016-0029

Sikora, L., Fournier, K., & Rebner,

J. (2019). Exploring the impact of individualized research consultations using

pre and posttesting in an academic library: A mixed

methods study. Evidence Based Library

& Information Practice, 14(1),

2–21. https://doi.org/10.18438/eblip29500

Suarez, D. (2013). Making sense of liaison

consultations: Using reflection to understand information-seeking behavior. New Library World, 114(11/12), 527-541.

https://doi.org/10.1108/NLW-04-2013-0036

Watts, J., & Mahfood, S. (2015).

Collaborating with faculty to assess research consultations for graduate

students. Behavioral & Social Sciences

Librarian, 34(2), 70–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639269.2015.1042819

Appendix A

Student Consultation

Questionnaire Questions

Hello, you had a research consultation with a U-M librarian this past

winter semester. How well do you remember this consultation?

●

Not at all

●

A little

●

Fairly well

●

Very well

Approximately how long did your consultation take?

●

0–10 Minutes

●

10–20 Minutes

●

20–30 Minutes

●

30+ Minutes

What was your program of study at the time of your consultation?

●

Bachelor’s

●

Master’s

●

PhD

●

Postdoc

●

Other

What is your expected year of graduation?

What major, program, or department were you

affiliated with at the time of your consultation?

Was this for a class?

●

Yes

●

No

(If “Was this for a class? Yes”) What class was this for? (e.g., ENGLISH

125) [Optional]

Can you briefly summarize what your consultation was about?

What did you hope to learn from the consultation?

Thinking about your answer above, do you feel that the consultation met

your expectations?

●

Significantly

●

Somewhat

●

A little

●

Not at all

(If “Thinking about your answer above, do you feel that the consultation

met your expectations? NOT Not at all”) In what ways

did the consultation meet your expectations?

(If “Thinking about your answer above, do you feel that the consultation

met your expectations? Not at all”) Please tell us why the consultation service

did not meet your expectations.

What, if anything, did you discuss during the consultation that was new

to you?

Were you working on a project/assignment when you scheduled your

consultation?

●

Yes

●

No

(If “Were you working on a project/assignment when you scheduled your

consultation? Yes”) To what extent did this service improve the quality of your

project/assignment?

●

Significantly

●

Somewhat

●

A little

●

Not at all

(If “To what extent did this service improve the quality of your

project/assignment? NOT Not at all”) In what ways did

the consultation service improve the quality of your project/assignment?

(If “To what extent did this service improve the quality of your

project/assignment? Not at all”) Please tell us why you didn’t think that the

consultation service improved the quality of your project/assignment.

Did you come to this consultation because you needed sources (e.g.,

materials such as books or articles to use for your research)?

●

Yes

●

No

(If “Did you come to this consultation because you needed sources (e.g.,

materials such as books or articles to use for your research)? Yes”) Were you

able to locate higher quality sources than before the consultation?

●

Yes

●

No

(If “Did you come to this consultation because you needed sources (e.g.,

materials such as books or articles to use for your research)? No”) Please

explain why not.

(If “Did you come to this consultation because you needed sources (e.g.,

materials such as books or articles to use for your research)? Yes”) What made

these sources better for your project/assignment?

(If “Were you working on a project/assignment when you scheduled your

consultation? Yes”) Did you get any feedback related to your project/assignment

from your instructor or supervisor?

●

Yes

●

No

(If “Did you get any feedback related to your project/assignment from

your instructor or supervisor? Yes”) What feedback did you receive from your

instructor or supervisor?

Were you able to use something that you discussed during your

consultation for your project/assignment?

●

Yes

●

No

(If “Were you able to use something that you discussed during your

consultation for your project/assignment? Yes”) How were you able to apply what

you discussed?

Were you able to apply something that you discussed during your

consultation to OTHER projects/assignments (i.e., different

projects/assignments than the one for which you scheduled a consultation)?

●

Yes

●

No

(If “Were you able to apply something that you discussed during your

consultation to OTHER projects/assignments (i.e., different

projects/assignments than the one for which you scheduled a consultation)?

Yes”) How were you able to apply what you discussed?

How would you describe the consultation service to a friend?

Would you recommend the consultation service to a friend?

●

Yes

●

No

(If “Would you recommend the consultation service to a friend? No”) Why

not?

If you would be willing to let us contact you with potential follow-up

questions, please enter your email address.

Appendix B

Librarian Consultation

Interview Questions

Introductions

[Ask the librarian what they know about the project, then fill in gaps

based on what they don’t know yet. If they don’t know about the project, read

the summary below.]

For those who conducted multiple consultations, do they want to talk

about each consultation individually or all at the same time?

1.

What was the student’s project?

2.

Did the research consultation take the full half hour?

Otherwise, how long did it take?

3.

What prior research on the topic had the student

conducted?

4.

What was your impression of the student’s research

skills at the start of the session?

5.

What goals did you have for the session? That is, what

did you want the students to walk away from the session having learned?

6.

What steps did you take to help the student answer

their questions?

7.

What did the student learn?

a.

Skills

b.

Concepts

8.

On a scale of one to ten, ten being highly successful,

one being not successful, how successful was the session? Why did you give them this rating?

9.

Did the student contact you after the consultation?

10.

In your estimation, was the research consultation

service the most appropriate mode for what the student needed to learn?

a.

If no, what other mode might have been more

appropriate?

b.

If yes, what did the student learn from this session

that would have been difficult to teach in another mode?

11.

Is there anything that you wish that the student had

learned during the consultation?

12.

May we contact you with any follow up questions?