Review Article

Information Literacies of PhD Students in the Health

Sciences: A Review of Scholarly Articles (2009 - 2018)

Elisabeth Nylander

Research Librarian

Jönköping University Library

Jönköping, Sweden

E-mail: elisabeth.nylander@ju.se

Margareta Hjort

Instruction Librarian

Jönköping University Library

Jönköping, Sweden

E-mail: margareta.hjort@ju.se

Received: 26 Aug. 2019 Accepted: 1 Nov. 2019

![]() 2020 Nylander and Hjort. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2020 Nylander and Hjort. This

is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29630

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible in part by the

Institute of Museum and Library Services (RE-95-17-0025-17). We thank the

Research Training Institute of the Medical Library Association for its

training, support, and encouragement to carry out this research. We thank our

Library Director Mattias Lorentzi for providing us

with the opportunity to conduct this project. We also thank Anna Abelsson and Thomas Mattsson for

comments on the manuscript.

Abstract

Objective – Doctoral studies offer a unique

phase in the development and legitimization of researchers, in which PhD

students shift from the consumption to the production of knowledge. If

librarians are to support this process in an evidence based

manner, it is essential to understand the distinct practices of this user

population. While recent reviews exist concerning the information behaviours of

graduate students and researchers, there is little knowledge synthesis focused

on the information literacies of PhD students in specific disciplines. The aim

of this article is to explore the depth and breadth of recent evidence which

describes the information literacies of students pursuing a doctoral degree in

the health sciences.

Methods – Strategic searches were performed

in databases, hand-searched key journals, and reference lists. Records were

screened independently by both authors based on pre-determined criteria.

General trends within the literature were mapped based on the extraction of the

following data: geographic location, population, study aims, and method of

investigation. Further analysis of the articles included charting the academic

disciplines represented, summarizing major findings related to PhD students in

health sciences, and which databases indexed the relevant articles.

Results – Many studies fail to treat doctoral

studies as a unique process. PhD students are often grouped together with other

graduate students or researchers. Studies tend to be based on small

populations, and the number of PhD students involved is either unclear or only

equals a few individuals within the entire group of study. In addition, of the

limited number of studies which focus exclusively on PhD students, few conduct

explicit examination of information practices in the health sciences. The

result is that this user group is underrepresented within recent journal

publications.

Conclusion – This review highlights the need for

more primary, in-depth research on the information literacies of PhD students

in the health sciences. In addition, librarians are encouraged to share their

knowledge in scholarly publications which can reach beyond their own

professional circles.

Introduction

A

practical objective of library and information science (LIS) is to investigate

the information practices of different groups in order to be able to invest in

appropriate information resources and services. Understanding the information

literacies of PhD students is of particular importance to academic libraries,

since these students are often present or future faculty, and librarians can

provide support in the transformation from students to scholars (Fleming-May

& Yuro, 2009).

Information Literacy – Debate and

Definitions

Information

literacy (IL) has traditionally been defined by organizations in terms of

explicit learning goals for the use of information. Several models for IL have

been put forth over the past few decades, including the recent Association of

College and Research Libraries’ (ACRL) “Framework for Information Literacy for

Higher Education”. This document represents an effort to shift from normative

standards to a more nuanced definition of IL as “the set of integrated

abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the

understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of

information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in

communities of learning” (American Library Association, 2015).

As a

research field, IL has been under development and debate for several decades (Bruce, 2000; Pinto, Cordón, & Díaz, 2010;

Tuominen, Savolainen, & Talja,

2005); however, it can be asserted that IL is now a well-established concept

within its own mature research domain (Bruce, 2016). For the purposes

of this review, the concept information

literacies is used in the plural form to denote

dynamic learning activities that take place through interactions within

specific social contexts. In other words, information skills evolve in domain

specific areas such as disciplines or communities of practice (Lave &

Wenger, 1991; Nicolini, Gherardi,

& Yanow, 2003). This

situated understanding of IL “calls for empirical research efforts to analyze

how specific communities use various conceptual, cultural, and technical tools

to access printed and digital documents and to evaluate and create knowledge”

(Tuominen et al., 2005, p. 342).

Information

Literacies of PhD Students

There

is a wealth of research regarding information practices within educational

settings, but few studies have concentrated on PhD students as a discrete

group. In a meta-synthesis of the literature on graduate students’

information-seeking behaviour, Catalano (2013) only found 11 studies published

between 1997 and 2012 that focus specifically on PhD students. These studies

typically center around efforts to improve library services, e.g., identifying

information source preferences or investigating research and writing processes

during a literature review. Catalano’s (2013) review considered graduate

students on both the master’s and doctoral level, and only a few patterns of

behaviour were pointed out as unique to PhD students. Like master’s students,

PhD students were found to begin their research on the Internet. However, PhD

students were also more inclined to consult their faculty advisors when seeking

information.

Spezi

(2016) augmented Catalano’s (2013) findings through a narrative review covering

the years 2010 – 2015, focusing on whether there has been a change in PhD

students’ information seeking behaviours due to developments in information and

communications technologies. Only a handful of the identified research looked

solely at PhD students, instead most studies grouped PhD students together with

other graduate students or with other researchers. Spezi’s

(2016) review confirms Catalano’s (2013) earlier observation that PhD students

are inclined to begin their searches on the Internet and that this is now an

established and recognized trend. At the same time, library e-resources are,

after “a period of disenchantment”, still useful enough to compete with web

searches. Spezi (2016) also points to the previously

documented importance of academic journals to PhD students during the research

process, and that more articles tend to be read in the medical and life

sciences. PhD students were also found to over-estimate their ability to search

for information effectively, e.g., constructing effective search strategies.

Disciplinary Differences and the Health

Sciences

In

LIS research, there has been a tendency to generalize about metadisciplines,

i.e., group fields into broad discipline categories such as science or the

humanities (Case & Given, 2016). Against this backdrop, a common assumption

is that scholars within the natural sciences mainly use journals and humanities

scholars mainly use archives and books. These generalizations “may be true as

they go, but they do not further our understanding of the important mechanisms

of information seeking, nor are they particularly useful in application, as in

designing university information systems to serve particular disciplines” (Case

& Given, 2016, p. 288). As noted previously, there is a strand of LIS

research which asserts the importance of the disciplinary context. Disciplines

have different research cultures and traditions (Talja,

Vakkari, Fry, & Wouters,

2007) and an “academic discipline ‘disciplines’ its members to behave in

certain ways” (Sundin, Limberg, & Lundh, 2008, p.

22). For this review, the health sciences as a

concept is defined as narrower than a metadiscipline

but wide enough as a field to encompass several smaller disciplines of science,

which focus on health or health care, e.g., medicine or nursing.

PhD

students are a unique library user group, marked by a period of transition.

They are not merely graduate students; they are researchers in training.

Academic disciplines provide the social contexts through which PhD students

learn what it means to be information literate in their fields. Although there

have been recent reviews about the information-seeking behaviour of PhD

students, there is little knowledge synthesis about these students that is

connected to the broader concept of information literacies or to the

discipline-specific culture of the health sciences.

The

aim of this article is therefore to explore the depth and breadth of research

in scholarly articles concerning the information literacies of PhD students

within the health sciences.

To

“identify the nature and extent of research evidence” and to provide “a

preliminary assessment of the potential size and scope of available research

literature” (Grant & Booth, 2009, p. 101), a review of scholarly articles

was conducted based on scoping review methodologies (Arksey & O'Malley,

2005; O’Brien et al., 2016; Peters et al., 2015).

This

review involved structured searches of subject-specific as well as

multidisciplinary databases for the years 2009 – 2018. This date range was

chosen in order to locate the most current publications available on the topic

of IL. While the phrase information literacy was introduced as early as

the 1970s (Zurkowski, 1974), it can be argued that IL

has only recently been established as a research domain (Bruce, 2000; Bruce, 2016).

Different databases were searched to identify the scope of the evidence,

i.e., not only what research is available but also where. LISA

(Library & Information Science Abstracts) was chosen to find research

within LIS and ERIC (Education Resource Information Center) for education.

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), MEDLINE, and

PsycINFO were used to broaden the search to encompass the health sciences.

Scopus was chosen in order to cover multidisciplinary publications. Search

strings were constructed using the individual databases’ thesauri in

combination with variations of the keywords doctoral

student and information literacy.

Searches were conducted in September 2018 and detailed documentation of the

strategies, including which database platforms were used, is provided in the

Appendix.

Through

a series of test searches, the following four journals were recognized as

particularly relevant for additional hand-searching: College & Research

Libraries, EBLIP (Evidence Based Library & Information Practice),

Journal of Academic Librarianship, and Journal of Information

Literacy.

The

inclusion criteria of this review are reflected within its search strategies

and screening criteria. It was limited to peer-reviewed journal articles that

report on empirical evidence written in English. This narrow focus was used to

identify publications that are commonly used and perhaps most valued by

professionals supporting PhD students within the health sciences, e.g.,

academic supervisors and medical or academic librarians. Commentaries and

essays were excluded, as were theses and dissertations, conference proceedings,

book chapters, and policy papers, since these documents tend to be secondary

sources rather than primary studies. Review articles were also excluded, but

only after consulting the reference lists of these articles to identify

additional original studies.

The

included research articles could employ qualitative, quantitative, or mixed

methods. The information literacies of PhD students could be examined from the

perspective of the PhD students themselves or from other groups involved in

doctoral studies, such as thesis supervisors or librarians. However, the

articles had to clearly identify and examine PhD students within the health

sciences as a distinct group.

Both

authors conducted the the literature search, screening, and data extraction.The

search results were imported into EndNote Desktop for de-duplication according

to a comprehensive and strategic method (Bramer, Giustini, De Jong, Holland, & Bekhuis,

2016) and then independently screened using Rayyan (Ouzzani,

Hammady, Fedorowicz, & Elmagarmid, 2016). Conflicting decisions were discussed in

order to reach consensus. The following data was charted from the included

studies: geographic location, population, aims, methodology, academic

disciplines represented, major findings related to health

sciences, and which databases indexed the relevant articles.

Results

Identification of Relevant Articles

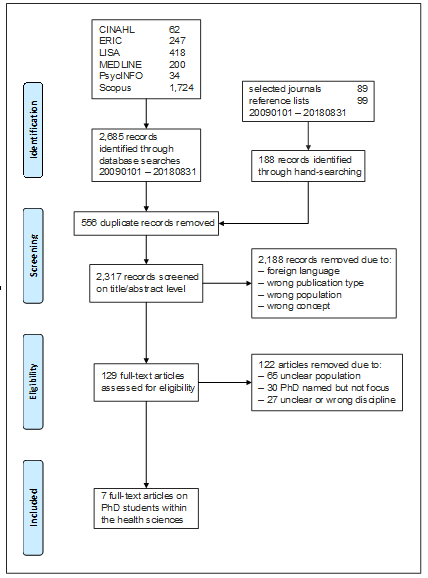

An adapted version of the PRISMA flow diagram

(Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff,

Altman, & Group, 2009) summarizes the search and screening process (Figure

1). The literature search identified 2,685 records and an additional 188

records were found through hand-searching. After duplicates were removed, the

titles and abstracts of the 2,317 remaining records were screened independently

by both authors.

Full-text was retrieved for 129 articles. Following

full-text screening, only seven articles (0.3% of the initial data set of 2,317

records) met the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1

Modified PRISMA diagram.

Indexing Practices

Table 1 shows which databases indexed the relevant

articles. The journals represented were mainly within LIS (six of the seven),

apart from one journal within education. None of the databases indexed all

seven articles, but all the articles were retrieved through Scopus, a

multidisciplinary database. LISA indexed all six LIS journals, but not the

education journal. In addition to the education journal, ERIC indexed two of

the six LIS journals. None of the articles were found in the databases covering

nursing or medical research, i.e., CINAHL and MEDLINE. However, PsycINFO

indexed the education journal and five of the six LIS journals.

Included Articles – Respective

Journals and Database Indexing

|

Article |

Published In |

CINAHL |

ERIC |

MEDLINE |

PsycINFO |

Scopus |

|

(Carpenter, 2012) |

Information Services & Use |

NO |

NO |

NO |

YES |

YES |

|

(Edwards & Jones, 2014) |

Evidence Based Library and Information Practice |

NO |

NO |

NO |

YES |

YES |

|

(Green, 2010) |

Journal of Academic Librarianship |

NO |

YES |

NO |

YES |

YES |

|

(Grigas, Juzeniene, &

Velickaite, 2017) |

Information Research |

NO |

YES |

NO |

NO |

YES |

|

(Ramlogan, 2014) |

Library Philosophy and Practice |

NO |

NO |

NO |

YES |

YES |

|

(Trafford & Leshem, 2009) |

Innovations in Education and Teaching

International |

NO |

YES |

NO |

YES |

YES |

|

(Warburton & Macauley, 2014) |

Australian Academic and Research Libraries |

NO |

NO |

NO |

YES |

YES |

The Nature of the Evidence

This

review revealed that the literature rarely treats doctoral studies as a unique

process. PhD students are usually grouped together with other graduate students

or researchers (65 articles with an unclear population, 30 articles with PhD

students named but not the focus). Studies tend to be based on small

populations, and the number of PhD students involved is either unclear or only

equals a few individuals within the entire group of study. Few studies were

about PhD students in the health sciences (27 with unclear or wrong

discipline). In other words, we assert that PhD students in the health sciences

are underrepresented in recent scholarly journals.

Only

seven articles met the inclusion criteria. The following synthesis is based on

the extracted data from these articles. Table 2 provides an overview of the

geographic locations as well as the populations, aims, and methodologies

reported in the articles. The studies took place in predominately

English-speaking countries such as the UK, the US, and Australia. PhD

populations varied greatly in size from under 20 (Green, 2010) to several

thousand (Carpenter, 2012), but the exact number of PhD students representing

health sciences was often unclear (Carpenter, 2012; Green, 2010; Ramlogan,

2014; Trafford & Leshem, 2009). Four studies were

about the PhD students themselves or their academic supervisors/librarians

(Carpenter, 2012; Green, 2010; Trafford & Leshem,

2009; Warburton & Macauley, 2014), and three studies investigated written

scholarly output, i.e., citation practices (Edwards & Jones, 2014; Grigas et al., 2017; Ramlogan,

2014).

Table 2

Overview of

Included Articles

|

Article |

Country |

Population |

Aim |

Methodology |

|

(Carpenter, 2012) |

UK |

6,161

Generation Y (born 1982 - 1994) doctoral students and 7,432 older doctoral

students; cohort of 30 full-time doctoral students |

Identify the

research behaviour among doctoral students in Generation Y |

Mixed; three

annual surveys and a longitudinal, qualitative cohort study |

|

(Edwards & Jones, 2014) |

US |

107 doctoral

dissertations |

Compare how

well library collections support doctoral research |

Quantitative;

citation analysis |

|

(Green, 2010) |

US and

Australia |

42 participants

including 5 American and 6 Australian librarians, 8 American and 10

Australian doctoral candidates, and 6 American and 7 doctoral advisors |

Examine and

reconsider the assumption that doctoral students are information illiterate |

Qualitative;

interviews coded through grounded theory |

|

(Grigas et al., 2017) |

Lithuania |

39 doctoral

theses |

Evaluate how

useful freely available full-text information sources can be when writing PhD

theses; determine to what extent the library may be an information resource

provider and intermediator |

Quantitative;

citation analysis |

|

(Ramlogan, 2014) |

Jamaica |

696

theses/dissertation checks |

Examine the

service of thesis and dissertation checking provided by liaison librarians |

Quantitative;

statistical analysis |

|

(Trafford & Leshem, 2009) |

UK |

55 PhDs, 7

supervisors, texts from examiners |

Identify the

difficulties that doctoral candidates encounter |

Qualitative;

open-ended questionnaire, discussions, and text analysis, all coded into

vignettes |

|

(Warburton & Macauley, 2014) |

Australia |

79 PhD

candidates and 32 PhD supervisors |

Profile PhD

candidate usage of research consultation service; explore if consultations

make a difference in the early stages of the PhD candidature |

Mixed;

open-ended questionnaire, survey, both online |

Both

quantitative and qualitative methods were used to achieve the aims of the

studies. Citation analysis was employed within two of the articles (Edwards

& Jones, 2014; Grigas et al., 2017) to evaluate

various aspects of library services for PhD students, e.g., relevance of

library collections and the usefulness of freely available full-text

information. Numerical evidence concerning the provision of thesis/dissertation

checking was presented in one study (Ramlogan, 2014). Interviews and grounded

theory were used to challenge the assumption that PhD students are information

illiterate in one study (Green, 2010). Several qualitative methods, including

coding into vignettes, were used within one study to identify the difficulties

that PhD students encounter (Trafford & Leshem,

2009). Mixed methods, i.e., a combination of surveys and interviews, were used

within two of the articles (Carpenter, 2012; Warburton & Macauley, 2014).

The aims of these latter studies included comparing research behaviour based on

generational differences and determining the impact of early research consultation

services during candidature.

The Breadth and Depth of the Evidence

Table

3 charts the discipline-specific data collected from the articles. While all

the articles focused on PhD students, it was often difficult to locate data

specific to the health sciences. For two of the articles (Ramlogan, 2014;

Trafford & Leshem, 2009), no data could be

identified relating to health science PhD students in particular. For one

article (Green, 2010), the data fit under generalizations made for the entire

population of study regardless of discipline. For the remaining four articles

(Carpenter, 2012; Edwards & Jones, 2014; Grigas

et al., 2017; Warburton & Macauley, 2014), the reporting was clearer

concerning which findings pertained to PhD students in the health sciences, but

the amount of data was limited. The health science most commonly named was

medicine (Carpenter, 2012; Grigas et al., 2017;

Ramlogan, 2014; Trafford & Leshem, 2009;

Warburton & Macauley, 2014), and all the studies examined other disciplines

outside the health sciences at the same time, e.g., education or engineering.

Table 3

Health Science

(HS) Discipline-Specific Data from Included Articles

|

Article |

HS Population |

HS discipline(s) |

Other discipline(s) |

Usability of Findings |

Major HS Findings |

|

(Carpenter, 2012) |

Number of

respondents from HS disciplines is unclear |

Medicine,

dentistry & health, veterinary sciences |

Social

sciences, engineering & computer sciences, arts & humanities,

biomedical sciences, physical sciences, biological sciences |

2012 report

based on studies performed in 2007 and 2009; limited amount of data that

could be identified as specific to HS discipline |

E-journals

dominate as a research resource for HS students; cohort students strongly

indicate that difficulty accessing and obtaining relevant resources due to

licensing is a severe constraint on their research; citation databases and

e-journal search interfaces are equally as popular as Google; with the

exception of veterinary sciences, PhD students work alone and not in

collaborating research teams |

|

(Edwards & Jones, 2014) |

Out of 107 dissertations,

28 (26%) within psychology and 22 (21%) within social welfare |

Psychology,

social welfare |

Education |

Clear

discipline- specific reporting yet limited amount of data that could be

charted |

Psychology

students cited the highest percentage of journals; social welfare students

cited free web resources (primarily government documents or reports from NGOs

and advocacy groups) but psychology students did not; both disciplines cited

older material than anticipated; surprisingly cross-disciplinary nature of

research, e.g., social welfare students frequently cited journals in

psychology |

|

(Green, 2010) |

Number of

respondents from HS discipline is unclear |

Nursing |

Education,

physical & biological science |

Limited amount

of data that could be identified as specific to HS discipline |

PhD students

from all disciplines indicated that they used the strategy of backward and

forward citation tracking to evaluate the quality of sources and expand their

bibliographies; most PhD students developed their literacy skills without

direct instruction; librarians are predisposed toward the view that PhD

students are information illiterate |

|

(Grigas et al., 2017) |

Out of 39

theses, 2 (5%) within psychology and 5 (13%) within medicine |

Psychology,

medicine |

Humanities,

social sciences, biomedical sciences, technological sciences, physical

sciences |

Clear

discipline-specific reporting yet limited amount of data that could be

charted |

PhD students

from the biomedical sciences are substantial users of peer-reviewed

e-journals; biomedical sciences students use books and e-books less than

students within the humanities |

|

(Ramlogan, 2014) |

Unclear

reporting for 176 theses/dissertation checks; out of 520 theses/dissertation

checks, 47 (9%) within medical sciences yet unclear if on master’s or PhD

level |

Medical

sciences |

Science &

agriculture, humanities & education, engineering, social sciences |

Focus is on

prevalence of the service rather than the impact it has on PhD students; no

data that could be charted as specific to HS discipline |

Not applicable |

|

(Trafford & Leshem, 2009) |

Number of

respondents/documents from HS discipline is unclear |

Bio-medical

sciences |

Botany,

management and business, education, English, geography, history, law,

linguistics, surveying |

No data that

could be identified as specific to HS discipline |

Not applicable |

|

(Warburton & Macauley, 2014) |

43.4% of PhD

candidates and 40.6% of

PhD supervisors within

medicine, dentistry and health sciences (MDHS) |

MDHS |

Arts,

education, engineering, architecture, building & planning, veterinary

science, business & economics |

Clear

discipline-specific reporting yet limited amount of data that could be

charted |

More than half

of part-time MDHS candidates rated their information skills as "less

than adequate"; 78.8% of MDHS students spoke of information

"chaos", "floundering" and "random" approaches

to locating information; the main reasons MDHS students sought library

research assistance were for help with search terms and keywords, and for

literature searching strategy design; 100% of MDHS students thought library

consultations could assist in refining literature search strategies and 88%

thought consultations could assist in undertaking thorough or systematic

literature searching |

Summarising the Evidence

Overall,

the studies identified in this review provide a regrettably limited amount of

data about the information literacies of PhD students in the health sciences.

It has already been noted that few studies in recent LIS literature are devoted

solely to PhD students, and the results of this review confirm this knowledge

gap. Even fewer studies were found addressing information literacies specific

to health science disciplines, and the few studies identified were mainly found

in LIS journals.

Discussion

Comparing the Evidence

The

small amount of relevant data available for analysis (Tables 2 and 3)

corresponds well with the previous discoveries of Catalano (2013) and Spezi (2016).

As

established by Catalano (2013), several studies were centered around efforts to

improve library services (Edwards & Jones, 2014; Grigas

et al., 2017; Ramlogan, 2014; Warburton & Macauley, 2014). In keeping with

a common assumption in LIS research (Case & Given, 2016, p. 288), Spezi (2016) confirmed the importance of academic journals

to PhD students and that more articles tend to be read in the medical sciences.

The same evidence is found in the article reporting on the largest population

(Carpenter, 2012) as well as the two smaller studies based on citation analysis

(Edwards & Jones, 2014; Grigas et al., 2017).

Both Catalano (2013) and Spezi (2016) observed that

PhD students are inclined to begin searching on the Internet; however, Spezi also argued that library e-resources are still able

to compete with web searches. This varied approach was also reported in the

Carpenter article (2012).

A few

new findings were discerned from the limited data of the included articles.

While Spezi (2016) described how PhD students

over-estimate their ability to search for information effectively, the students

in the study by Warburton and Macauley (2014) often rated their skills as “less

than adequate” and spoke of information “chaos”, “floundering”, and “random”

approaches to locating information. Green (2010) asserts that librarians are

predisposed toward the view of PhD students as information illiterate and calls

for the profession to question this assumption; in part this is because the

students in Green’s study were found to develop their literacy skills without

direct instruction.

Additional

findings moved beyond information-seeking and discovery into the realm of “how

information is produced and valued” (American Library Association, 2015). While

Edwards and Jones (2014) found students cited older material than anticipated,

Green (2010) reported that students strategically tracked citations backward

and forward in order to evaluate the quality of sources and expand their

bibliographies. Regarding “the use of information in creating new knowledge and

participating ethically in communities of learning” (American Library

Association, 2015), Warburton and Macauley (2014) discovered that students

mainly sought library research assistance for their information-seeking, i.e.,

search terms, keywords, and strategy design. It should be noted that their

respondents were very confident in library research support, e.g., 100% thought

that library consultations could refine search strategies and 88% thought they

could get help with thorough or systematic searches. With regards to

communities of learning, Carpenter (2012) reported that PhD students in

medicine, dentistry, and health generally worked alone and not in collaborating

research teams.

Charting the Evidence Base

As indicated in Table 1, the few relevant articles

identified in this review were mainly found in LIS journals.

However, if librarians wish to inform faculty about IL and how librarians can

help, it is the disciplinary publications which faculty value that can serve as

the most effective medium (Stevens, 2007). In the health sciences, these

publications are usually scholarly articles found in databases such as PubMed.

Within the LIS community, there is a call for evidence based library and information practice (Booth,

2002; Crumley & Koufogiannakis, 2002) and a

concern that there is not enough research from which to draw conclusions. As a

former editor of the Journal of the Medical Library Association remarked,

“We have many articles; we do not have a body of evidence” (Plutchak,

2005). In an overview identifying research gaps, Koufogiannaikis

and Crumley (2006) also noted several issues that librarians face when publishing

articles, including a lack of indexing and open access options in LIS journals.

Where is the evidence about information literacy to be

found and who is publishing this research? In a small-scale reference analysis

of articles on how academic libraries contribute to student success, findings

suggest an uneven relationship between LIS and other disciplines. More

specifically, LIS is borrowing concepts and methods from the field of

education, but other disciplines rarely cite LIS research (Kogut, 2019). Another exploratory study investigating the

visibility of librarians as authors in scholarly journals within higher

education, teaching, and learning between 2000 and 2012, found that less than

2% of articles published in these journals were written by librarians; while IL

was the most common topic for librarians, most articles were theoretical and

not based on empirical research (Folk, 2014). Pilerot

(2014) notes in another small-scale investigation how the established

assumption is that there is a disconnect between research and practice, and

that the prevailing gap-metaphor should be abandoned to allow for a more

nuanced discussion between librarians as a professional group and LIS faculty.

Is there a gap in the evidence base concerning the IL of PhD students in the

health sciences? This review points to the possibility, but perhaps there is

also too little communication between library practice, library research, and

those who benefit from both.

Limitations

This review is not without its limitations. Very few

studies met the narrow inclusion criteria. Generally, the populations of the

studies were small and researchers rarely ascribed their findings to

discipline-specific practices, resulting in findings that are almost anecdotal

in nature, making it difficult to track larger trends. IL was mapped as an

established concept, but more studies might have been located if the search

strategies had included classic LIS terminology such as information-seeking or

literacy skills, or if the date range

had been extended to include research from earlier decades. This review

may have also missed articles where IL was not named, but rather described as a

particular strategy such as help from

librarians or using journal

articles. Additional studies might have also been found if PhD students

had not been treated as unique user group, i.e., labels like graduate students

or researchers were used. Moreover, the inclusion of professional doctorates

such as MD or DPharm might have also led to a broader

review.

A great deal of investigative work devoted to this

population is probably being carried out by LIS professionals, and not just by

LIS researchers. If more health science librarians were to disseminate the

results of their own research, a solid evidence base could be established

within our profession (Koufogiannakis & Crumley,

2006). More knowledge about how PhD students interact with libraries is likely

to be found in librarians’ grey literature, such as conference posters and

institutional reports. Therefore, future attempts to map this user population

should also include searches of the grey literature. In addition, if enough

original studies are found devoted to this population, these should be

subjected to some form of critical analysis before data extraction, to increase

the trustworthiness of any resulting synthesis.

This review found that PhD students in the health

sciences are underrepresented in current scholarly journals. Out of over 2,500

possible records, only seven articles met the inclusion criteria. From these

seven, six were found in LIS journals, resulting in a lack of evidence about

how to support the information literacies of this population. Future LIS

research should address this deficiency by studying PhD students as a unique

group operating within discipline-specific communities. Furthermore, it is

recommended that more health science librarians share their professional

experiences in publications that reach beyond their own institutions or

organizations, e.g., peer-reviewed articles in journals which are indexed in

databases such as CINAHL or MEDLINE.

References

American Library Association. (2015). Framework for information literacy for higher education. Retrieved

from http://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework

Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a

methodological framework. International

Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Booth, A. (2002). Evidence-based librarianship: One small step. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 19(2),

116-119. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-1842.2002.00373.x

Bramer, W.M., Giustini, D., De Jong, G.B., Holland, L., & Bekhuis, T.

(2016). De-duplication of database search results for

systematic reviews in endnote. Journal of

the Medical Library Association, 104(3), 240-243. https://doi.org/10.3163%2F1536-5050.104.3.014

Bruce, C. (2000). Information literacy research: Dimensions of the

emerging collective consciousness. Australian

Academic and Research Libraries, 31(2), 91-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2000.10755119

Bruce, C.S. (2016). Information literacy research: Dimensions of the

emerging collective consciousness. A reflection. Australian Academic and Research Libraries, 47(4), 239-244. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2016.1248236

Carpenter, J. (2012). Researchers of tomorrow: The research behaviour of generation Y doctoral students. Information Services & Use, 32(1-2),

3-17. https://doi.org/10.3233/ISU-2012-0637

Case, D.O., & Given, L.M. (2016). Looking for information: A survey of research on information seeking,

needs, and behavior. Bingley: Emerald.

Catalano, A. (2013). Patterns of graduate students' information seeking

behavior: A meta-synthesis of the literature. Journal of Documentation, 69(2), 243-274. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411311300066

Crumley, E., & Koufogiannakis, D. (2002).

Developing evidence-based librarianship: Practical steps for implementation. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 19(2),

61-70. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-1842.2002.00372.x

Edwards, S., & Jones, L. (2014). Assessing the fitness of an

academic library for doctoral research. Evidence

Based Library & Information Practice, 9(2), 4-15. https://doi.org/10.18438/B81K5T

Fleming-May, R., & Yuro, L. (2009). From

student to scholar: The academic library and social sciences PhD students'

transformation. Portal: Libraries and the

Academy, 9(2), 199-221. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.0.0040

Folk, A.L. (2014). Librarians as authors in higher education and

teaching and learning journals in the twenty-first century: An exploratory

study. The Journal of Academic

Librarianship, 40(1), 76-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2013.12.001

Grant, M.J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis

of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Green, R. (2010). Information illiteracy: Examining our assumptions. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 36(4),

313-319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2010.05.005

Grigas, V., Juzeniene, S., & Velickaite, J. (2017). “Just google it” – The scope of freely available information sources for

doctoral thesis writing. Information

Research, 22(1). Retrieved from http://informationr.net/ir/22-1/paper738.html

Kogut, A. (2019).

Information transfer in articles about libraries and student success. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 45(2),

137-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.02.002

Koufogiannakis, D.,

& Crumley, E. (2006). Research in librarianship: Issues to consider. Library Hi Tech, 24(3), 324-340. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378830610692109

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated

learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff,

J., Altman, D.G., & the PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for

systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4),

264-269. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135

Nicolini, D., Gherardi, S., & Yanow, D.

(2003). Introduction: Toward a practice-based view of knowing and learning in

organizations. In D. Nicolini, S. Gherardi,

& D. Yanow (Eds.), Knowing in organizations: A practice-based approach (pp. 3-31).

Armonk, NewYork: M.E. Sharpe.

O’Brien, K.K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D.,

Baxter, L., Tricco, A.C., Straus, S., Wickerson, L., Nayar, A., Moher,

D., & O’Malley, L. (2016). Advancing scoping study methodology: A web-based

survey and consultation of perceptions on terminology, definition and

methodological steps. BMC Health Services

Research, 16, 305. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1579-z

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z.,

& Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan-a web and mobile

app for systematic reviews. Systematic

Reviews, 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Peters, M.D.J., Godfrey, C.M., Khalil, H., McInerney,

P., Parker, D., & Soares, C.B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic

scoping reviews. International Journal of

Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141-146. https://doi.org/10.1097/xeb.0000000000000050

Pilerot, O. (2014).

Connections between research and practice in the information literacy narrative:

A mapping of the literature and some propositions. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 48(4), 313-321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000614559140

Pinto, M., Cordon, J.A., & Diaz, R.G. (2010). Thirty years of

information literacy (1977-2007): A terminological, conceptual and statistical

analysis. Journal of Librarianship and

Information Science, 42(1), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0961000609345091

Plutchak, T.S. (2005).

Building a body of evidence. Journal of

the Medical Library Association, 93(2), 193-195. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1082934/

Ramlogan, R. (2014). Theses and dissertations at the University of the

West Indies, St. Augustine: A liaison librarian's input. Library Philosophy and Practice, 1-12. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/1150/

Spezi, V. (2016). Is

information-seeking behavior of doctoral students changing?:

A review of the literature (2010–2015). New

Review of Academic Librarianship, 22(1), 78-106. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2015.1127831

Stevens, C.R. (2007). Beyond preaching to the choir: Information

literacy, faculty outreach, and disciplinary journals. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 33(2), 254-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2006.08.009

Sundin, O., Limberg, L., & Lundh, A. (2008). Constructing librarians' information literacy expertise in the domain of

nursing. Journal of Librarianship and

Information Science, 40(1), 21-30. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0961000607086618

Talja, S.,

Vakkari, P., Fry, J., & Wouters,

P. (2007). Impact of research cultures on the use of digital

library resources. Journal of the

American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(11), 1674-1685.

https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20650

Trafford, V., & Leshem, S. (2009). Doctorateness as a threshold concept. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 46(3),

305-316. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703290903069027

Tuominen, K., Savolainen, R., & Talja, S. (2005). Information literacy as a sociotechnical

practice. Library Quarterly, 75(3),

329-345. https://doi.org/10.1086/497311

Warburton, J., & Macauley, P. (2014). Wrangling the literature:

Quietly contributing to HDR completions. Australian

Academic and Research Libraries, 45(3), 159-175. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2014.928992

Zurkowski, P.G. (1974). The

information service environment: Relationships and priorities. Related Paper

No. 5. Washington, D.C.: National Commission on Libraries and Information

Science.

Appendix

Database Searches

|

Database |

Search String |

Limiters |

|

CINAHL (EBSCOhost) |

(MH "Students, Graduate" OR TI (doctoral

OR doctorate OR post-graduate OR postgraduate OR graduate OR phd OR “doctor of philosophy”) OR AB (doctoral OR

doctorate OR post-graduate OR postgraduate OR graduate OR phd

OR “doctor of philosophy”)) AND |

Peer Reviewed; Published Date: 20090101-20180831;

English Language |

|

ERIC (EBSCOhost) |

(DE "Doctoral Programs" OR TI (doctoral

OR doctorate OR post-graduate OR postgraduate OR graduate OR phd OR “doctor of philosophy”) OR AB (doctoral OR

doctorate OR post-graduate OR postgraduate OR graduate OR phd

OR “doctor of philosophy”)) AND |

Peer Reviewed; Published Date: 20090101-20180831;

English Language |

|

LISA (ProQuest) |

(MAINSUBJECT.EXACT("Graduate studies")

OR ti(doctoral OR doctorate OR post-graduate OR

postgraduate OR graduate OR phd OR "doctor of

philosophy") OR ab(doctoral OR doctorate OR post-graduate OR

postgraduate OR graduate OR phd OR "doctor of

philosophy")) AND (MAINSUBJECT.EXACT("Information literacy")

OR ti(information AND (literacy OR literacies)) OR

ab(information AND (literacy OR literacies))) |

Peer Reviewed; Date: From 2009 January 01 to 2018

August 31; English Language |

|

MEDLINE (EBSCOhost) |

(MH "Education,Graduate"

OR TI (doctoral OR doctorate OR post-graduate OR postgraduate OR graduate OR phd OR “doctor of philosophy”) OR AB (doctoral OR

doctorate OR post-graduate OR postgraduate OR graduate OR phd

OR “doctor of philosophy”)) AND |

Published Date: 20090101-20180831; English Language |

|

PsycINFO (ProQuest) |

(MAINSUBJECT.EXACT("Postgraduate

Students") OR ti(doctoral OR doctorate OR

post-graduate OR postgraduate OR graduate OR phd OR

"doctor of philosophy") OR ab(doctoral OR doctorate OR post-graduate

OR postgraduate OR graduate OR phd OR "doctor

of philosophy")) AND (MAINSUBJECT.EXACT("Information

Literacy") OR ti(information AND (literacy OR

literacies)) OR ab(information AND (literacy OR literacies))) |

Peer reviewed; Date: From 2009 January 01 to 2018

August 31; English Language |

|

Scopus (Elsevier) |

TITLE-ABS-KEY (information AND (literacy OR

literacies)) AND (doctoral OR doctorate OR post-graduate OR postgraduate OR

graduate OR phd OR "doctor of

philosophy") |

AND DOCTYPE(ar) AND PUBYEAR > 2009 AND LANGUAGE(english) |

All searches were performed on September 21, 2018.