Research Article

An Analysis of Student Performance at the Intersection

of Diversity and Information Literacy

Nastasha E. Johnson

Assistant Professor of

Library Science

Physical and Mathematical

Sciences Information Specialist

Purdue University Libraries

and School of Information Studies

Purdue University

West Lafayette, Indiana,

United States of America

Nathan Mentzer

Associate Professor

Engineering/Technology

Teacher Education

Dept of Technology

Leadership & Innovation

Dept of Curriculum and

Instruction

Purdue University

West Lafayette, Indiana,

United States of America

Received: 26 Apr. 2018 Accepted: 26 Apr. 2019

![]() 2019 Johnson and Mentzer. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2019 Johnson and Mentzer. This is an Open

Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

DOI: 10.18438/eblip29438

Abstract

Objective – When teaching

Information Literacy (IL) concepts, instructors often have no knowledge about

the background or previous IL exposure of the students they are teaching.

This study aims to create a holistic

picture of the students at a large Midwestern United States university in a first year introductory course on the design process for

solving engineering problems.

Methods – Institutional

data and course level data were traced and linked to individual students in an

introduction to design thinking first year course. This course is at a major

high research activity institution in the Midwestern United States. From a

total course size of 650, institutional and course level data of 127 students

were selected randomly and analyzed. Some data points are self-reported and some

data points are performance-based.

Results – Underrepresented

minorities (URMs) had a higher increase in IL score from assignment 1 to

assignment 3 than non-URM students. However, non-URMs performed higher on both

the first and the last assignments. Students in concurrent IL designated

courses had a higher increase from assignments 1 to 3 than those not in

simultaneous IL designated courses. Black and international students had the

highest increases from assignments 1 to 3 of any demographic. Regarding IL, the

fact that none of the students had been exposed to much IL instruction

justified continued collaboration in the course between the instructor of

record and the IL specialist. There were significantly negative correlations

between the final grade and first-generation status. Legacy students also

performed more poorly from assignments 1 to 3.

Conclusion – Students are more diverse in a single

classroom setting than presumed prior to research; therefore, our instructional

practices should be diverse and inclusive, as well. More preparation work and

fact finding should be conducted by library faculty and instructors to

facilitate the learning of the students, and not just the act of teaching.

Librarians could ask for more information about the course demographics and

respond accordingly. Librarians should also be properly trained in

instructional practices to be better equipped to meet the expectations and

challenges of teaching a diverse class.

Introduction

In higher education, library faculty and instructors

rarely know about the backgrounds of the students we teach. We are often

encouraged to teach to a variety of types of students, not completely

understanding what that means or looks like in the context of our individual

classes. Furthermore, librarians may be at a disadvantage, not knowing the

information literacy (IL) skills of the students that we teach. We may be

invited to speak on a topic, with little to no knowledge about what they are

preparing for and how much they may already know. Information literacy

instruction sometimes occurs as if in a vacuum, with little knowledge about the

background and IL exposure of the students taught. This same lack of knowledge

often applies when we design our own courses. We often

teach what we want them to know, but not what they are prepared to

understand.

Not only are past IL experiences ignored, so are

students’ concurrent research and IL experiences. We know that preparedness

gained in high school can have an impact on performance in college, including

research practices (McCarron & Inkelas, 2006). Preparedness

can sometimes be related to the rigor and resources of their high schools (Roderick, Coca, & Nagaoka, 2011) but also

to family finances (Bettinger, 2004; Castleman & Long, 2016) or not

having exposure to those who have attended college before, i.e.,

first-generation college students (Bui, 2002; Pike & Kuh, 2005; Stroud, 2017). There

have been many studies on the intersection of gender and grade performance,

especially in STEM disciplines (Hubbard, 2005; Severiens & ten Dam, 2012).

Furthermore, information literacy and library usage are positively correlated

with student matriculation (Soria, Fransen, & Nackerud,

2013).

In the LIS literature, the relationship between student success and

information literacy has been well documented. In 2014, Soria, Fransen, and Nackerud conducted a

series of regression analyses of over 5000 students and found that students who

had used the library resources and services at least once in the first year had

a higher GPA than those who did not. Though several data points were collected,

they did not specifically report about the performance differences of students

along ethnicities, income, and other “pre-college” data. There was an

opportunity to explore the library use and exposure along with a variety of

data points, which this study will do.

The LIS profession is continuously challenged to think

beyond race and ethnicity to include other diversity measures. Specifically, we

were challenged to expand our definition of diversity to include

“underrepresented, disadvantaged, and underserved in terms of information” (Jaeger, Subramaniam, Jones, & Bertot, 2011, p. 11). Based on their definitions, diversity expands

to include any people who may not have the best access to information, whether

it is because of language barriers, access to technology, or statistical status

as a minority. According to Fabbi’s (2015) research on the use of the iSkills assessment

of information and computer testing, she found that there are four predictive

variables to a high school student’s success: student’s best language, race,

cumulative GPA score and honors/non-honors curricular paths. This was supported

by Huerta and Watt’s (2015) work that also said that GPA and AP courses in high

school predicted college success. After

high school, more research is needed to explore those predictive variables over

time. Conversely, Lanning and Mallek (2017) found that students’ high school performance and demographics had no

influence on their information literacy performance. They collected demographic

and high school information, along with admission test scores. Only their

current GPA and ACT were relevant in their post-test regression analysis of IL

performance.

Library instruction and cultural competence is an

emerging area of interest for researchers. Understanding diversity is quite

different than being culturally competent and adept when working with people

who are different than you, especially in an instructional setting. Lori S.

Mestre’s research (2009) has been looking at cultural competence in K-12 and

college environments. In 2009, she published a work that found a significant

gap in the cultural competence training of librarians before professional

positions (Mestre, 2009). She

found that such training would help librarians modify their instruction to be

more culturally non-offensive (Mestre, 2009). In

2010, in the book Librarians Serving

Diverse Populations (Mestre, 2010) she

expanded on her earlier research to suggest how librarians could be trained in

intercultural competence, as well as in strategies for library administration

and library school curriculum development to effect positive change for

professionals and pre-professionals. Some of the efforts include strategic

assessment and ongoing training on incorporating multiculturally sensitive

stories in the lesson planning (Mestre, 2010, pp. 100-101).

In 1991, Marilyn Loden and Judy Rosener

published pioneering work on the dimensions of diversity (Loden & Rosener, 1991). In their book, they

introduced the diversity wheel, with primary and secondary levels of diversity

of individuals and institutions. The first level of diversity represents the

internal dimensions of diversity, characteristics that influence self-identity.

The six dimensions on the first level are age, gender, sexual orientation,

physical ability, ethnicity, and race. The second level of diversity represents

external characteristics that influence social identity. The 10 dimensions on

the second level are: marital/family status, parental status, geographic

location, income, personal habits, recreational habits, first language, work

experience, educational background, and work experience. The original

dimensions were expanded in 2010 to include income, class, and spiritual

beliefs. These dimensions and characteristics of diversity can influence how

people value themselves and those around them. Because of the value placed on

these dimensions, individually and collectively, the dimensions of diversity

can positively or negatively influence interpersonal interactions in the

classroom (Milem, Chang, & Antonio, 2005).

Understanding these dimensions and where students appear within the social

construct of the classroom is within the realm of responsibility for teaching

faculty who are interested in effectively teaching to all walks of students (Milem et al., 2005). For

this study, we will relate these dimensions of diversity with student

performance on assignments to understand more about their performance along those

dimensions. The dimensions are many of the data points collected by the

university or self-reported by students at admission. We will collate those

variables to create a holistic picture of the students in the course studied.

Background of the Course

According to the Association of American Colleges and Universities

(AACU) Information Literacy VALUE Rubric, information literacy is “the ability

to know when there is a need for information, to be able to identify, locate,

evaluate, and effectively and responsibly use and share that information for

the problem at hand” (Association of American College and Universities, 2019). In the

classroom setting it may be manifest as written assignments, projects, or other

learning objects that require research and producing an assignment or

experience. According to criterion 3 of the AACU rubric, the student should be

able to evaluate information and its sources critically. Additionally, in

criterion 5, students should access and use information ethically and legally.

The course studied, TECH 120, is a first-year gateway course which introduces

students to design thinking for solving problems. The steps of the design

thinking include utilizing available information at each step, including defining the problem,

brainstorming solutions, and developing and testing a prototype. The AACU IL

standards, not the current or previous ACRL IL standards, are the approved

definitions used to create the “information literacy” core curriculum

designation by University Administration at the institution where the study was

held. The learning objectives for this course, and others that are considered

core curriculum IL designated courses at the institution, are created using the

AACU IL standards.

TECH 120, Technology and the Individual, an introduction to technology

design, typically enrolls approximately 650 students each year, most of whom go

on to pursue majors in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM)

disciplines. It is the gateway course to the College of Technology and is a

required course for all of the majors in that College. Most of the students are

first-year students. TECH 120 also fulfills the information literacy course

category of the general education core curriculum requirements that all

students must complete before graduating. A librarian has been an integral part

of the course design and has contributed information literacy-related content

through the entire length of the semester-long course, including assistance

with rubric design and assignments.

Student assignments are produced along the design thinking continuum of

designing prototypes, including three IL-specific assignments that were

analyzed as a part of this study. The first assignment is a bibliography

created by the students on pedestrian safety at crosswalks, after watching a

librarian-created video on keyword selection and the basic use of the databases

Google Scholar, Engineering Village, and Academic Search Premier. The second

assignment is a repeat of the first assignment, after a librarian in-class

visit to review the databases and answer questions about their experiences. At

the end of the semester, as a final project and the third assignment of this

study, students produce academic-style poster presentations about a

technological problem and solution within their College. A bibliography section

is included in the rubric for this assignment and is also a part of the

optional templates provided. The self-selected problems vary from

mechanical/facilities problems to student time-management problems.

Aims

This study aims first to create a holistic picture of the lives of the

students in a single technology course; capturing demographic data, high school

rank, Pell Grant eligibility, college transcript, and other institutional data

and assessments. We want to investigate which demographics and common

categories of diversity, i.e., underrepresented minorities (URMs),

first-generation and legacy students (relatives,

usually children, of a graduate of a school), and family financial

contribution, correlate to their IL performance in a first-year course. We also

investigate how students perform who have taken IL courses before or

concurrently.

Methods

Two separate IRB approvals were granted for this

study. The first IRB protocol enabled the ethical use of the student

assignments for citation analysis. The second IRB protocol granted consent to

engage in data agreements with Financial Aid, the Registrar, and Admissions for

the ethical use of the institutional data of the students studied in the first

IRB. The institutional data was paired with the citation scores of the

assignments completed by the students.

Variables

There are 11 non-IL independent variables in this

project, along with 3 IL dependent variables. The variables are defined in

Table 1.

Table 1

Project Variable

Definitions

|

High

School Name & Location |

secondary

institution listed on the student’s transcripts, geographic location |

|

Course

Grade Data Final grade letter & value |

the

final grade submitted to the registrar’s office, and its weight |

|

Major |

selected course of undergraduate study |

|

Gender |

commonly

referred to as “sex”, self-identified biological and physiological

characteristics that denote male and female, as defined by the World Health

Organization |

|

Ethnicity |

identified

as having the physical characteristics of a particular ethnic or cultural

group; one of 6 options: 2+ Races, Asian, Black/African American,

Hispanic/Latinx, International, White; includes non-domestically/foreign born |

|

Underrepresented

Minority (URM) status |

university assigned; denotation of the student as an underrepresented racial minority, such as Latinx,

African American/Black, or Asian American.

Does not include non-domestically/foreign born |

|

Semester

GPA |

cumulative

grade point average with all coursework in the semester studied |

|

Overall

GPA |

cumulative

grade point average with all coursework in entire college career |

|

First

generation status |

whether

a student’s parents have not attended or graduated from a higher education

institution |

|

Legacy

status |

whether

a student’s parents or other immediate family members have attended the

institution where the study was held |

|

Birthdate |

the date when a student was born |

|

Pell

Grant eligibility |

whether

a student’s financial contribution or family’s contribution makes them

eligible for need-based federal financial aid, i.e. how much of the cost of

education can be provided by the student and/or the parents. |

|

Assignment

one |

an

annotated bibliography collected and analyzed using the rubric in the Appendix,

before librarian-led instruction |

|

Assignment

three |

a

bibliography collected and analyzed using the rubric in the Appendix at the

end of the course |

|

Average

(Avg) IL Difference |

average difference in the citation scores between assignment 1

and assignment 3 |

|

Concurrent

IL Status |

whether student is enrolled in another IL designated core

curriculum course during the same semester such as Freshmen English |

Citation Analysis Process

A 127-student sample population was randomly

selected from a total 650-student course, across 17

sections. Each of the students was assigned a number, and numbers were selected

using an online randomizer, www.randomizer.org. Student assignments were

collected and analyzed using a customized three-point scale rubric based on the

CRAAP test (Meriam Library, 2010) on the

elements of currency, relevance, authority, accuracy, and purpose of the

citations rendered. The author created a 3-point scale to measure the merit of

each criterion, from low (1) to high (3). Three separate assignments were

collected: 1) a bibliography after watching an online IL video, 2) a

bibliography created after a librarian-facilitated face-to-face session, and 3)

an end-of-course project bibliography. However, for this study, we evaluated

the difference in IL performance from assignment 1 and assignment 3. That is,

we evaluated the difference between an assignment early in the semester with an

assignment at the end of the semester. Those IL results were then paired with

institutional data about each student. Four librarians, in two teams of two,

normed the citation scores of the students’ assignments to establish

inter-rater reliability. The librarians randomly selected 10 assignments, measured

them individually, and then discussed them to normalize the scores given.

Librarians met three times to discuss the scores due to the number of

assignments and to ensure consistency over time. The librarians were from

different disciplines or departments, in order to minimize the subjective bias

inherent with being familiar or unfamiliar with the disciplines that the

students cited.

Institutional Data Collection

Data sources include the campus learning management

system, the campus Office of Institutional Research, Assessment and

Effectiveness, and the Financial Aid office. Some data points, such as the

first-generation status, are self-reported, and other data points are

performance based. Data were retrieved via IBM Cognos Analytics, which is web

modeling and analysis software. All identifiable data were anonymized by a

campus data analyst prior to being shared with the other authors. Project

metadata was kept via a shared Google document.

Data were stored using Excel spreadsheets. Data analysis was conducted

using Minitab, Excel, and Tableau. We used descriptive and inferential

statistics to determine how different demographics and preparedness affect

performance. Minitab was used to calculate Pearson correlations to determine

whether or not there were any associations between variables. Next, Excel was

used to test for significance. One-sided t-tests and ANOVA t-tests were

conducted to determine p values. Cohen’s D was used to determine effect size. A

t-test’s statistical significance indicates whether or not the difference

between groups’ means most likely reflects a real difference in the population

from which the groups were sampled. Finally, Tableau was used to create data

visualizations to get a view of the demographic breakdowns.

Results

After compiling the data, we found the overall demographics of the

class. Students from outside of the College of Technology comprised 9% of those

enrolled, which means that 91% were College of Technology majors. The class

consisted of 81% that were self-identified as male, 69% white, and 13%

underrepresented minorities. A total of 76% of the students were freshmen.

Concurrent Enrollment in an IL Course

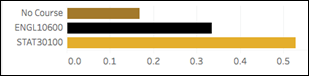

A total of 62% of TECH 120 students were not concurrently enrolled in

another information literacy core curriculum course. However, 32.28% (41)

students were also enrolled in ENGL 106, the cornerstone English course

required by all freshmen. Another 5.51% (7) were enrolled in STAT 301, which

also fulfilled the IL requirements as required by the university.

Figure

1

Percentage

of students in concurrent IL course.

Figure 2

Citation score

difference of students in concurrent IL course.

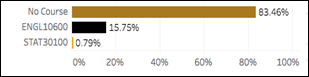

Prior Enrollment in an IL Course

Most students, 83.46%, had not completed an IL categorized core

curriculum course prior to enrollment in this course. However, one student who

scored considerably worse on both assignments had taken STAT 301 previously and

had the largest difference between assignments.

Figure

3

Percentage

of students who previously enrolled in IL course.

Figure

4

Citation

score difference of students who previously enrolled in IL course.

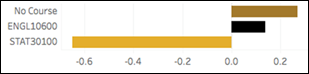

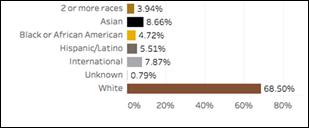

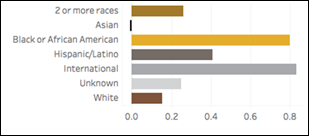

Ethnicity

In terms of ethnicity, 68.50% (87) of the students identified as white

and 8.66% (11) of the students identified as Asian or Asian American. In terms

of nationality, 7.87% (10) students were identified as International students

or non-domestically born. Nearly 10% of the students were identified as an

underrepresented minority, with 4.72% (6) Black/African American, 5.51% (7)

Latinx, and 5 (3.94%) that identified themselves as multiracial.

Figure

5

Ethnic

backgrounds of the students.

Figure

6

Citation

score difference by ethnic background.

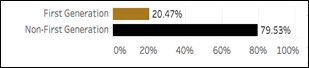

First Generation Status

First-generation college students made up 20% (26) of

the sample. There were 101 students (79.53%) who reported that at least one

parent or both parents had attended a higher education institution.

Interestingly, the difference in IL performance was greater with non-first generation students than first-generation students.

That is, students who were exposed to family members who had a college

education had a greater performance gap than those who did not have a family

member who had attended college.

Figure

7

First

generation status of students.

Figure

8

Citation

score difference based on first generation status.

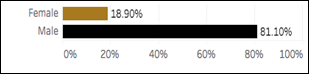

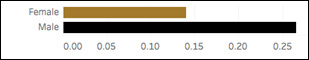

Gender Status

Only 24 students (18%) were female, while the remaining 81% were male.

The difference in IL performance was greater among male students than female

students.

Figure

9

Gender

of the students.

Figure

10

Citation

score difference by gender.

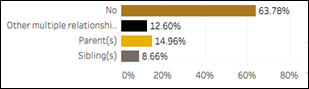

Legacy Status

A total of 63.78% (81) of the students were not the immediate family

members of university alumni. The remaining students had a parent, sibling, or

another relative that attended the university. Most students with relatives who

attended the university had a positive IL performance difference from

assignment 1 to assignment 3. However, students whose parents attended the

university had a negative IL performance difference, which means that they

actually did worse on the final assignment than the first assignment.

Figure

11

Legacy

status of the students.

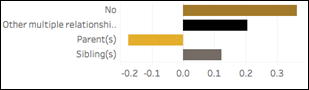

Figure 12

Citation score difference by legacy status.

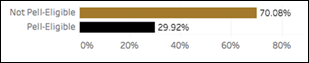

Pell Grant Eligibility

Although 89 students were not eligible for the Pell Grant, 30% (38) of

students were eligible for the grant. Those who were eligible for a Pell Grant

had a greater IL difference, denoting a larger improvement from assignment 1 to

assignment 3.

Figure

13

Pell

Grant eligibility by student.

Figure

14

Citation

score difference by Pell Grant eligibility status.

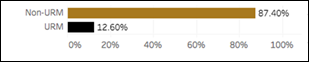

Underrepresented Minority Status

A significant majority of students, 87% (111), were not underrepresented

minorities. A count of 16 students identified as URM; 13% of students were

identified as Black/African American, Asian American, or Latinx. Based on the

ethnicity data, multi-racial students may also be grouped with underrepresented

minorities. This is unclear, but the data supports this as a possibility.

Students who were URM had a larger IL difference from assignment 1 to

assignment 3 than those who were non-URM.

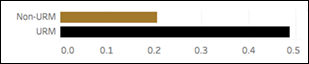

Figure

15

Underrepresented

Minority status.

Figure

16

Citation

score difference by Underrepresented Minority status.

Information Literacy

Overall with all variables controlled, the average citation score for

all students was 2.289 on the first IL assignment, on a scale of 1 to 3, with

30 students scoring below 2. The overall average citation score on the second

assignment was 2.532, with 3 students (8.66%) scoring below 2. This suggests

growth in overall IL performance for the entire sample of 127 students from

assignment 1 to assignment 3.

Table 2

Average Citation

Score, cumulatively

|

|

Assignment #1 |

Assignment #3 |

|

Average IL Score |

2.289940031 |

2.532168551 |

Discussion

Diversity

Diversity within higher education can be defined along many variables; including,

but not limited to, gender, ethnicity, URM status, and economic contributions.

Research has shown that gender (Moss-Racusin, Dovidio, Brescoll, Graham, & Handelsman, 2012)) does

influence the performance of females in STEM. There are inherent and explicit

biases in the classroom that can dictate the success of a diverse group of

students (Greenwald & Krieger, 2006; Gregory, Skiba, & Noguera, 2010;

Hill, Corbett, & St Rose, 2010; Jacoby-Senghor, Sinclair, & Shelton,

2016; Staats, 2015).

According to the findings, there was a significantly negative correlation

between the IL performance of URM students and their course grade, suggesting

the grades of URMs decreased in relation to minority status. There were no

other significant correlations found between those variables identified as

pertaining to diversity, gender, and Pell grant eligibility. Our findings are

supported by the literature that URMs can perform more poorly academically in

certain settings. However, our study found no significant differences along

gender lines nor economic status.

Table 3

T-Tests Scores

Comparing URM Status, Gender, and Pell Grant Eligibility Status with IL

Performance

|

|

URM (Y=1) |

Gender (M=1) |

Pell-eligible (Y=1) |

|

IL 1 |

-0.093 |

-0.072 |

-0.062 |

|

IL 3 |

0.05 |

-0.017 |

0.004 |

|

Change in IL |

0.12 |

0.063 |

0.064 |

|

TECH

120 Grade |

-0.209* |

-0.087 |

-0.109 |

|

F14 Term GPA |

-0.127 |

-0.142 |

-0.1 |

*Statistically

significant at p<.05

Exposure

An important interest in the study was to find the influences of

pre-college and concurrent college experiences on the performance of IL related

assignments. One of those influences is exposure to formal IL instruction in

other courses. We ran Pearson’s correlations to determine the relationship

between exposure to concurrent and prior courses. There was a significantly

negative correlation between the performances on assignment 1 and being

concurrently enrolled in another IL course. That is, students who were in two

IL designated courses simultaneously performed poorer on assignment 1 than

those enrolled in the single course. Different IL topics, techniques, and

course elements could be the reason for the difference in performance.

Librarian involvement could also be a contributing factor, as IL is a

significant portion of the learning outcomes for the course and the librarian

was significantly involved with the course design of the studied course. It is

unknown whether a librarian was involved with the design of other courses.

Preparedness

College readiness can be an accurate measure of performance capability

at the college level. College readiness is often denoted with the academic

rigor of the courses offered and taken in high school (Roderick et al., 2011).

However, college readiness can also be attributed to exposure through social

networks like family and fellow students (Bui, 2002). We

found that there was a significant negative correlation between the IL

performance of first-generation students and their GPA during the term of the

study. That finding suggests that first-generation students perform less than

their counterparts both in IL performance and overall for the course and the

term studied. This is consistent with existing literature regarding the

performance of first-generation students, justifying the need for support

interventions. Interestingly, legacy students had a negative average change in

IL score, meaning that their IL scores decreased over the course of the

semester. High school was not a significant correlation, though considered as a

preparedness factor. Only those students who attended high schools in the same

state of the study were included.

Table 4

T-Test Scores

Comparing First-Generation Status, Legacy

Status, and High School Rank

|

First Generation (Y=1) |

Legacy

(Y=1) |

HS

Rank (n=79) |

|

|

IL 1 |

0.04 |

0.135 |

0.093 |

|

IL 3 |

0 |

-0.165 |

-0.072 |

|

Change

in IL |

-0.04 |

-0.224* |

-0.138 |

|

TECH

120 Grade |

-0.254** |

-0.06 |

-0.029 |

|

F14

Term GPA |

-0.185* |

-0.087 |

-0.011 |

*Statistically

significant at p<.05

**Statistically

significant at p<.01

Conclusion

Students within a single course are more diverse than the eye can see.

They have complicated upbringings and have followed different paths to arrive

in the college classroom. From this study, we investigated the diversity of the

backgrounds of the students and aspects of their social network contributions,

tangible and intangible. We learned that having concurrent or prior IL

instruction may compromise the integrity of the IL instruction that took place

in this course because students who took prior or concurrent IL courses did not

perform as well as those who had not. This contradicts the study done by Soria

et al. about the use of the library databases (2014). More research is needed to explore what happens when students take

more than one research heavy or IL related course, especially in their first or

second years. Perhaps further work can be done to understand why more IL

instruction did not lead to a stronger performance in this study. Additionally,

we learned that the impact of the URM and international experience on their

overall performance cannot be overlooked in the IL instructional setting.

International and URM students experienced lower IL performance gains. More IL

related research and inclusive IL instructional practices should be explored to

engage traditionally underserved students, like URM and international students.

Perhaps considerations should be made for lower-income students, in regard to

the use of technology and prior exposure to IL that may have been limited prior

to their university arrival. That is to say, we can question whether every

student has every app or cool new technology device to adequately engage with

some course materials. Similar considerations may apply to first-generation

students understanding the nuances of navigating the academic setting,

including IL instruction and course and library materials. This study

demonstrates that in some instances instructor assumptions may not be supported

by data, and we instructors should make efforts to understand and teach the

whole student with equity, not equality..

References

Association of American Colleges & Universities.

(2019). Information literacy VALUE rubric. Retrieved from https://www.aacu.org/value/rubrics/information-literacy

Bettinger, E. (2004). How financial aid affects persistence. In C. M. Hoxby (Ed.), College choices: The economics of where to

go, when to go, and how to pay for it. (pp. 207-238). Chicago, IL:

University of Chicago Press.

Bui, K. V. T. (2002). First-generation college

students at a four-year university: Background characteristics, reasons for

pursuing higher education, and first-year experiences. College Student

Journal, 36(1), 3-12.

Castleman, B. L., & Long, B. T. (2016). Looking

beyond enrollment: The causal effect of need-based grants on college access,

persistence, and graduation. Journal of Labor Economics, 34(4), 1023-1073.

https://doi.org/10.1086/686643

Fabbi, J. L. (2015). Fortifying the pipeline: a quantitative exploration of

high school factors impacting the information literacy of first-year college

students. College & Research Libraries, 76(1), 31-42. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.1.31

Greenwald, A. G., & Krieger, L. H. (2006).

Implicit bias: Scientific foundations. California Law Review, 94(4),

945-967.

Gregory, A., Skiba, R. J., & Noguera,

P. A. (2010). The achievement gap and the discipline gap: Two sides of the same

coin? Educational Researcher, 39(1), 59-68. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09357621

Hill, C., Corbett, C., & St. Rose, A. (2010). Why so few? Women in science, technology,

engineering, and mathematics. Washington, DC: American Association of

University Women.

Hubbard, L. (2005). The role of gender in academic

achievement. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 18(5),

605-623. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390500224887

Huerta, J., & Watt, K. M. (2015). Examining the

college preparation and intermediate outcomes of college success of AVID

graduates enrolled in universities and community colleges. American

Secondary Education, 43(3), 20-35.

Jacoby-Senghor, D. S., Sinclair, S., & Shelton, J.

N. (2016). A lesson in bias: The relationship between implicit racial bias and

performance in pedagogical contexts. Journal of Experimental Social

Psychology, 63, 50-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.10.010

Jaeger, P. T., Subramaniam, M. M., Jones, C. B., &

Bertot, J. C. (2011). Diversity and LIS education:

Inclusion and the age of information. Journal of Education for Library and

Information Science, 52(3), 166-183.

Lanning, S., & Mallek,

J. (2017). Factors influencing information literacy competency of college

students. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(5), 443-450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2017.07.005

Loden, M., & Rosener, J.

B. (1991). Workforce America!: Managing employee

diversity as a vital resource. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

McCarron, G. P., & Inkelas,

K. K. (2006). The gap between educational aspirations and attainment for

first-generation college students and the role of parental involvement. Journal

of College Student Development, 47(5), 534-549. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2006.0059

Meriam Library, California State University-Chico.

(2010). Evaluating information – Applying the CRAAP test. Retrieved from https://library.csuchico.edu/sites/default/files/craap-test.pdf

Mestre, L. (2009). Culturally responsive instruction

for teacher-librarians. Teacher Librarian, 36(3), 8-12.

Mestre, L. (2010). Librarians serving diverse

populations: Challenges and opportunities. (ACRL publications in librarianship, 62). Chicago, IL: Association

of College & Research Libraries.

Milem, J. F., Chang, M. J., & Antonio, A. L. (2005). Making diversity

work on campus: A research-based perspective. Washington, DC: Association

of American Colleges and Universities.

Moss-Racusin, C. A.,

Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J., &

Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle

gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences, 109(41), 16474-16479. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1211286109

Osa, J. O., Nyana, S. A., & Ogbaa, C. A. (2006). Effective cross-cultural communication

to enhance reference transactions: Training guidelines and tips. Knowledge

Quest, 35(2), 22-24.

Pike, G. R., & Kuh, G.

D. (2005). First- and second-generation college students: A comparison of their

engagement and intellectual development. The Journal of Higher Education, 76(3),

276-300. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2005.11772283

Roderick, M., Coca, V., & Nagaoka, J. (2011).

Potholes on the road to college: High school effects in shaping urban students’

participation in college application, four-year college enrollment, and college

match. Sociology of Education, 84(3), 178-211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040711411280

Severiens, S., & ten Dam, G. (2012). Leaving college: A gender comparison in

male and female-dominated programs. Research in Higher Education, 53(4),

453-470.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-011-9237-0

Soria, K. M., Fransen, J.,

& Nackerud, S. (2013). Library use and

undergraduate student outcomes: New evidence for students' retention and

academic success. portal: Libraries and the Academy, 13(2), 147-164. https://doi.org/10.1353/pla.2013.0010

Soria, K. M., Fransen, J.,

& Nackerud, S. (2014). Stacks, serials, search

engines, and students' success: First-year undergraduate students' library use,

academic achievement, and retention. The Journal of Academic Librarianship,

40(1), 84-91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2013.12.002

Staats, C. (2015). Understanding implicit bias: What educators should know. American Educator, 39(4), 29-44.

Retrieved from: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1086492

Stroud, D. I. (2017). A quantitative exploration of

the educational paths to completion taken by first generation college students

and students who have a parent with a four-year college degree (Doctoral dissertation, University of

Missouri--Kansas City). ProQuest Dissertations

and Theses Global, 1927182146.

Appendix

Rubric – Citation Analysis, based on CRAAP Test

Currency: The timeliness of the information

- How old is the

information and is that important for your topic?

- Does it report facts

from the actual time of the event or issue?

- Is it retrospective,

providing some review or analysis of previous research?

Relevancy: The importance of the information for your needs

·

Does the information relate

to your topic or answer your question?

·

Who is the intended

audience?

·

Is the information at an

appropriate level (i.e., not too elementary)?

·

Have you looked at a variety

of sources before determining the appropriateness of this source?

Authority: The source of the information

·

Who is the author/creator of

the information? Is it a person, group of people, an organization?

·

Is he/she the original

author/creator?

·

Is the person qualified?

What are his/her credentials? What is his/her occupation?

·

Is the source sponsored or

endorsed by an institution or organization?

·

Is there a potential for

bias?

Accuracy: The reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of the content

·

Is the bias of the

author/creator obvious? Is the source trying to convince you of a point of

view?

·

Where does the information

come from? Is it supported by evidence?

·

Is the publication in which

the item appears published, sponsored, or endorsed by a political or other

special interest group?

·

Does the language or tone

seem unbiased or free of emotion?

·

Are there typos, spelling

errors, or grammatical errors?

Purpose: The reason the information exists

- What is the intended purpose of the information: inform, teach,

sale?

- Is the information fact, opinion, propaganda?

- Does the point of view appear objective and impartial?

- Are there political, ideological, culture, religious, institutional

leanings presented?

Considerations for Evaluators Scale – low (1) to high (3)

Currency: Timeliness

1-

Not Acceptable: No date indicated, inappropriate,

obsolete, or outdated for paper topic/assignment

2-

Acceptable: Should be used with sources from other

dates

3-

Completely Appropriate: Most timely for paper

topic/assignment

Relevancy: Importance of the

information to the topic/assignment

1-

Not At All Relevant/Partially

Relevant to Topic: show to minimal understanding of the relation between the

source and the paper topic/assignment; not appropriate for academic level &

audience

2-

Relevant to topic: Information relates to the topic;

shows some understanding of the relation between the source and the paper

topic/assignment; fairly appropriate for academic level & audience

3-

Completely Relevant: Information relates to the topic;

clear relation between the source and the paper topic/assignment; appropriate

for academic level & audience

Authority/Accuracy: Source

of the information

1-

Not Accurate/No Authority: Unedited/Unverifiable; no

to little accountability of the author; no author identified, potentially

biased

2-

Some Accuracy/Some Authority: Popular or unscholarly

source; demonstrates some understanding of the information

3-

Authoritative/Accurate: verifiable content, demonstrate

thorough understanding of the information, scholarly source

Purpose: Reason the

Information Exists (inform, sell, persuade)

1-

No Understanding/Minimal Understanding of the purpose

of the information

2-

Adequate understanding of the purpose of the information

3-

Expert understanding of the purpose of the source

understanding difference between fact and opinion; recognizing bias or

misinformation