Introduction

This

article analyzes an emerging type of public library program: movement-based

programs. These are programs that encourage, enable, and foster physical

activity and physical fitness (Lenstra, 2017). The literature review below

shows that although there is both research-based evidence that approximately

20-30% of public libraries in the United States offer movement-based programs

and anecdotal evidence that these programs are offered by public libraries

elsewhere in the world, the impacts and outcomes of these programs have

received little attention. This paper addresses this gap by presenting the

results from a survey of North American public libraries that have offered

movement-based programs.

Since

little was known about the impacts of movement-based programs in public

libraries, an exploratory survey design was used to address the following

research questions: what impacts do movement-based programs in public libraries

have and what variations exist between urban and rural libraries. Results show

that these programs tend to bring new users into libraries, contribute to

community building as well as to health and wellness. Most respondents (95%)

state that they intend to continue offering movement-based programs at their

public libraries. The article concludes by discussing how these results can

productively inform our understanding of the evolving roles of public libraries

in relation to public health and wellness.

Literature

Review

The

literature on movement-based programs in public libraries consists of three

types: 1) the inclusion of questions about movement-based programs in surveys

that focus on other facets of public librarianship, 2) case studies in which

researchers were participants in the experimental cases analyzed, and 3) short,

journalistic program reports shared in channels without peer-review or

expectations of adherence to research frameworks. This literature shows that

approximately 20-30% of U.S. public libraries have offered some form of

movement-based programming. Furthermore, the case studies and journalistic

reports suggest that these programs are also offered elsewhere around the

globe. Although this literature suggests that movement-based programs tend to

resonate with the populations served, no research has yet analyzed in detail

what impacts movement-based programs have. As a result, the profession has yet

to develop the means to communicate about physical activity in public libraries

to policy makers, to broader stakeholders, or even to itself.

Survey-based

research

Surveys

conducted during the last decade find that movement-based programs have been

offered in many public libraries throughout the United States. A randomized

survey of gaming programs in public libraries (Nicholson, 2009, p. 206) found

that “physical games” that require moving the body were the fourth most common

type of gaming program offered in public libraries. A follow-up study using

convenience sampling that included school and academic libraries found that

“the most popular game activity reported in 2006 gaming programs in libraries

was the Dance Dance Revolution series, with 44% of library programs

[reported] using this game” (Nicholson, 2009, p. 209).

More

recently, two surveys conducted in 2014 attest to the presence of yoga and

other fitness classes among the regular offerings of U.S. public libraries.

Among other questions, the 2014 Digital Inclusion Survey, conducted by

the Information Policy and Access Center at the University of Maryland, asked a

random sample of public libraries a series of questions related to health

programs and services they provided. One question asked respondents to state

whether or not their libraries had during the past year offered “fitness

classes (e.g., Zumba, Yoga, Tai Chi, other).” The survey found that

approximately 22.7% of U.S. public libraries had offered some sort of fitness

class (Bertot, Real, Lee, McDermott, & Jaeger, 2015, p. 62), with these

types of programs most common in suburban libraries (33.9%) and least common in

rural libraries (12.6%).

Another

survey conducted in 2014 came to similar conclusions. The Library Journal

Programming Survey asked a convenience sample of Library Journal

subscribers working in public libraries to answer questions about yoga programs

offered by their libraries. The survey found that 33% of respondents had

offered yoga programs during the last twelve months (Library Journal, 2014). Of

those public libraries that had offered yoga, 77% said they offered it for

adults, 27% for teenagers, and 40% for children. Of these three surveys, only Library Journal’s produced evidence on

the impacts of movement-based programs: 23% of libraries with yoga programs

said they had been very popular, 43% said popular, 28% said somewhat popular,

and only 6% said not at all popular.

Case study research

The

earliest research-based case study of movement-based programs in public

libraries was conducted by two public librarians in the early 1990s. Public

librarians in Connecticut collaborated with a local aerobics instructor to

develop a series for teenaged girls that included fitness classes. Interviews

with the teenaged participants revealed that the fitness components of the

program led to increased self-esteem and increased interest in regular physical

activity (Quatrella & Blosveren, 1994). It is unclear if the program

continued after the trial study. In any case, approximately 15 years later a

group of librarians from the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center

launched a series of programs for youth in local public libraries that included

exercise instruction (Woodson, Timm, & Jones, 2011). By tracking the

participants in these programs, the authors determined that the programs were

successful in that the children who participated had fun while learning about

health and wellness.

More

recently, three research-based case studies on movement-based programs in

public libraries were published in 2015 and 2016. Health science librarians

from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri partnered with the local

public library system to administer a community survey on health information

needs. The survey found that “exercise” was the topic the public most wanted to

see more of at the library (Engeszer et al., 2016, p. 64). In response, the

partners developed a series of programs that included yoga, beginning exercise,

and Zumba that was subsequently offered throughout the St. Louis Public Library

system.

A

similar study took place in the small town of Farmville, North Carolina, where

the public library partnered with a nearby library and information science

professor to develop programs and services that promote healthy lifestyles

(Flaherty & Miller, 2016). The library loaned pedometers to patrons and the

researcher interviewed those who participated. Participants reported liking the

program and asked for more movement-based programs at the library. In response,

the library organized a 5K race and a mile fun walk/run in Spring 2015, which

has since become an annual library-sponsored program. Based on the success of

these initiatives, the public librarian became the wellness coordinator for the

town.

In

Lethbridge, Alberta, public librarians collaborated with local and provincial

partners to develop a "library of things" initiative that involved

checking out supplies that could be used in physical activities (Cofell,

Longair, & Weekes, 2015; Weekes & Longair, 2016). The librarians

assessed the program by monitoring circulation trends and collecting feedback

from participants. They found that the circulating materials contributed to

increasing physical literacy and physical activity among participants.

Collectively

these studies show that diverse types of movement-based programs tend to be

popular with public library patrons. Nonetheless, these case studies are based

in particular places. Without analysis of libraries outside of those locations

it is difficult to make generalizations about the impacts of these types of

programs beyond the particular cases presented.

Short reports

of programs authored by public librarians

In

addition to the peer-reviewed research literature discussed above, short

reports concerning programs in public libraries have been published outside

peer-reviewed channels. These reports illustrate other types of movement-based

programs offered in libraries. In addition to the types of programs discussed

above, this literature reports on movement-based programs for early literacy

(e.g. Music and Movement) (Dietzel-Glair, 2013; Kaplan, 2014; Prato, 2014),

library-based community gardens (Peterson, 2017), dancing (Green, 2013; St.

Louis Public Library, 2014), StoryWalks® (Maddigan & Bloos, 2013), outdoor

activities like walking and bicycling (Hill, 2017; Richmond, 2012), and fitness

challenges (Hanson, 2012).[1]

Furthermore, these reports illustrate that movement-based programs are being

offered in public libraries in Canada (Maddigan & Bloos, 2013), the United

Kingdom (Vincent, 2014), Romania (EIFL, 2016), Namibia (Hamwaalwa, Teasdale,

McGuire, & Shuumbili, 2016), China (Zhu, 2017), and Singapore (National

Library Board of Singapore, 2017).

A lack of

evidence on the impacts of innovations in public library programs

One

would perhaps expect that the growth of movement-based programs in public

libraries would naturally lead to a growth of data collection on the spread and

impacts of these programs. However, the continued lack of evidence based

research on innovations in public library programs and services complicates

matters. In a guest editorial to a special issue of EBLIP focused on

public libraries, Ryan (2012) writes that

Despite

this welcome inclusion in EBLIP,

public librarian participation is notably low. This mirrors the grim reality of

low public librarian research and publication rates, as well as the small

overall percentage of LIS research articles about public library practice. (p.

5)

In

a recent follow-up to this special issue, Cole and Ryan (2016) note that “the

current state of evidence based practice and research on, and to inform, public

library practice lags significantly behind that of other library sectors” (p.

120). As a result of this state of affairs, there continues to be a great need

for research both on how public libraries are innovating, as well as on the

impacts of these innovations.

Within

the U.S. public library profession, one means of enabling librarians to

integrate evidence into their evolving practices has been the development of

the Project Outcome toolkit. The U.S.

Public Library Association’s Project Outcome seeks to create

standardized evaluation tools that public librarians can use to assess the

impacts of their services and programs (Anthony, 2016; Oehlke, 2016).

Nonetheless, despite this laudable goal there are significant gaps in the

coverage of Project Outcome. In particular, the toolkit provides no

means of assessing how libraries contribute to health and wellness. Project Outcome focuses on assessing

what it calls “seven essential library service areas,” including:

“civic/community engagement, early childhood literacy, education/lifelong

learning, summer reading, digital learning, economic development, and job

skills” (Public Library Association, 2017, n.p.). Despite a plethora of studies

showing that public libraries impact population health and wellness (e.g.

Gillaspy, 2005; Morgan, Dupuis, Whiteman, D’Alonzo, & Cannuscio, 2017;

Rubenstein, 2016), Project Outcome does not include any tools to assess

these outcomes. As a result, more work is needed to understand how public

libraries impact health as well as to prepare public librarians to incorporate

evidence into this service area. According to public health scholars and

policy-makers, regular physical activity is one of the best things for good

health (Kohl et al., 2012). The researcher aimed to investigate the impacts of

movement-based programs in public libraries to better understand the impacts of

physical activity in public libraries.

Aims

and Methods

Study design

Since

little was known about the general impacts of movement-based programs in public

libraries an exploratory survey design was used to address the research questions:

What

impacts do movement-based programs in public libraries have? What variations

exist between urban and rural libraries?

The

focus on disentangling differences between urban and rural libraries relates to

a continued divide between these two types of public libraries in the U.S.,

with entire professional associations focused around the concerns of these two

groups (i.e. The Association for Rural

& Small Libraries and the Urban

Libraries Council).

In

any case, in creating the data collection instrument (Appendix A), the author

looked to past surveys of public libraries (e.g. Bertot et al., 2015), as well

as to past literature on movement-based programs. In addition, the survey was

piloted with three public librarians, one each from Illinois, North Carolina,

and New Brunswick. These librarians helped inform the language used in the

final survey.

Data Collection

Public

libraries throughout North American were invited to self-select for

participation in the survey. The researcher hopes that in the future this

self-selecting sample can be supplemented by a randomized sample of public

libraries. Data collection was carried out via an online questionnaire using

Qualtrics. The URL to the questionnaire was sent to public librarians in the

U.S. and Canada through state and provincial library electronic mailing lists,

as well as through announcements from state and provincial libraries to public

libraries in their regions. In addition, the survey was disseminated through

national electronic mailing lists used by public librarians (e.g. PUBLIB) and

on the project’s website. Between February 14 and March 23, 2017 a

self-selecting sample of 1,828 public librarians began the “Let’s Move in

Libraries Survey”.

Data

Analysis

Respondents

were invited to complete as much or as little of the survey as they wished.

After removing partial responses (n=570) and responses from libraries that had

never offered any movement-based programs (n=101), a sample of 1,157 libraries

remained for analysis.

The

data were integrated with data from the Institute of Museum and Library

Services FY 2014 Public Libraries Survey (IMLS, 2016) to sort the respondents

into “urban,” “suburban,” “town,” and “rural” libraries, as well as to sort the

respondents by region. According to IMLS (2016) the major distinction between

urban/suburban and town/rural libraries is that the former are libraries

located within urban metropolitan areas and the latter are libraries located

outside those metro areas. All Canadian respondents (n=62), as well as 49 U.S.

respondents could not be integrated with the IMLS dataset. These 101

respondents were sorted by hand, using the methods of the IMLS, into these 4

geospatial divisions.

To

transform the data in ways that would allow for quantitative comparisons

between urban and rural libraries, the verbal options from which respondents

selected were translated into numbers. See Table 1 below for an example of how

this process was carried out. The number in the “average across all programs”

column on the right side of the table illustrates how comparisons were made

among libraries. For instance, in the example below Library 1 reported the most

satisfaction with program participation. The fact that program participation

“fell below expectations” in one of the movement-based programs offered at

Library 3 led to its composite measure being lower. Similar techniques enabled

comparisons among libraries in terms of the extent to which movement-based

programs had brought new users into libraries, and the extent to which the

media had reported on movement-based programs in libraries.

Findings

Description

of Sample

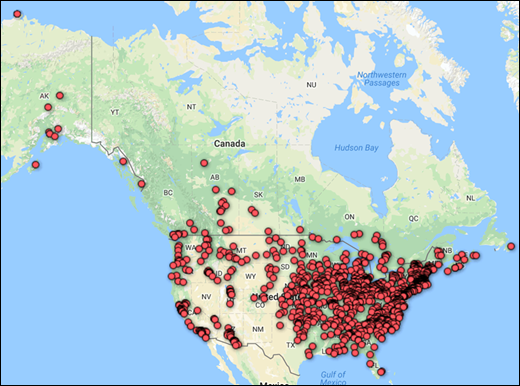

Figure

1 shows respondents’ physical locations. Although respondents are located in

many parts of North America, this self-selecting sample does not constitute a

statistically representative sampling of all public libraries that offer

movement-based programs. Nonetheless, as Table 2 shows, the respondents do

represent many types of communities, with a nearly even split between libraries

located within urban metro areas (54%) and libraries located outside metro

areas (46%).

Overall, respondents reported that their libraries

had offered

a wide variety of movement-based programs for a wide array of age groups. Yoga

programs were the most commonly reported type of program, offered in 65% of the

responding libraries (Figure 2), followed by movement-based early literacy

programs (55%), gardening (41%), dancing (36%), and StoryWalks® (29%). Most of the more frequently offered types of

movement-based programs were reported more frequently in urban and suburban

libraries than in town and rural libraries. However, other programs, including

StoryWalks®, “Other,” Outdoor activities, Fitness challenges, and Library of

Things initiatives were slightly more likely to be reported in town and rural

than in urban and suburban libraries.

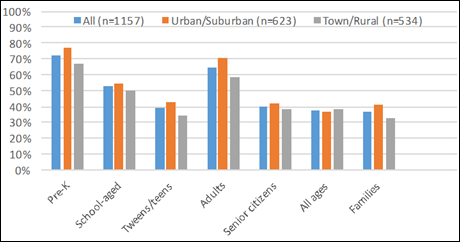

Respondents

reported offering movement-based programs for all age groups. Among

respondents, 73% had offered programs for Pre-K audiences, 52% for school-aged

youth, 39% for tweens and teenagers, 65% for adults, and 42% for senior

citizens. In addition, 38% reported movement-based programs for all ages and

37% reported programs for families (see Figure 3). Urban and suburban libraries

were more likely to have offered movement-based programs for all of the groups

asked about except for “all ages” programs, which were slightly more common in

town and rural libraries.

3. Users

The most consistently reported impact of

movement-based programs was that these programs brought new users into libraries.

For each type of movement-based program offered, respondents were asked whether

the program had (coded to “2”) or had not (“1”) brought new users to their

libraries. A significant number of respondents (n=183, or 16% of the sample)

did not know the answer to this question. Nonetheless, among those libraries

that did know, the vast majority reported new users coming to libraries because

of their participation in movement-based programs. The overall average was

1.86. There was a significant difference between urban/suburban (M=1.904,

SD=0.228) and town/rural (M=1.817, SD=0.317) libraries, conditions:

t(972)=4.942 p=0.0001. In other words, the tendency for movement-based programs

to bring new users to libraries was more accentuated in urban libraries.

4. Media

Even more respondents (n=242, or 21% of the sample)

did not know whether or not the media had reported on their libraries’

movement-based programs. Nonetheless, among those who did know the answer to

this question, the composite average was 1.55 (“2”=Yes, “1”=No). Furthermore,

there with a statistically significant difference between urban/suburban

(M=1.505, SD=0.442) and town/rural (M=1.591, SD=0.446) libraries, conditions:

t(912)=2.958, p=0.0032. In other words, movement-based programs tended to

receive slightly more media coverage in more rural libraries.

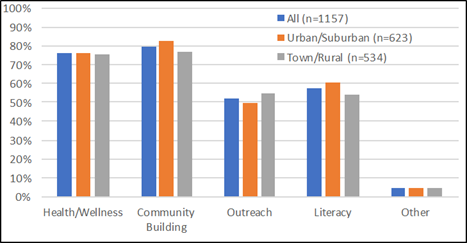

5. Outcomes

Finally, respondents were asked, based on any

feedback and evidence they may have collected, if their movement-based programs

had contributed to health or wellness, community building, outreach, literacy,

or other outcomes. Overall, only slight variation existed between

urban/suburban and town/rural respondents (see Figure 4). Interestingly, the

most commonly reported outcome was not health or wellness (76%), but rather

community building (80%). In addition, over 50% of respondents said that at

least one of their movement-based programs had contributed to outreach (52%) or

to literacy (58%), suggesting that movement-based programs contribute to

multiple outcomes in the public libraries that offer them.

The final measure of the impact of movement-based

programs in public libraries comes from the answer to the question: Will

libraries continue to provide these types of programs in the future? Nearly 95%

of respondents (n=1094) said their libraries plan to continue offering

movement-based programs.

Discussion

Similar to the Library

Journal survey (2014) that asked about yoga programs in U.S., this study

found that movement-based programs have been offered for multiple age groups.

There does not appear to be any one primary age group for these types of

programs. Nevertheless, the high percentage of respondents that reported

programs for Pre-K youth suggests that movement may be most integrated into

library programs for this age group, an assertion bolstered by the many program

development tools that discuss how to incorporate movement into programs for

Pre-K audiences in public libraries (e.g. Dietzel-Glair, 2013; Kaplan, 2014;

Prato, 2014). The extent to which movement has been integrated into library

programs for other age groups is less clear. However, in at least some

libraries it does appear that movement-based programs for diverse age groups

has become a normal part of library programming.

In any case, the results from this survey also suggest

that urban and suburban libraries may be offering slightly different types of

programs than their rural and town counterparts. In particular, the survey

found that programs that do not require the use of an indoor meeting space, or

that take place outside the library (such as StoryWalks®, Outdoor activities,

Library of things initiatives, and Fitness challenges) were offered more often

in town and rural libraries than in urban and suburban libraries. On the other

hand, the differences reported were slight. More research will be needed to

determine if the types of movement-based programs offered in public libraries

differ by the types of communities served.

The evidence on the impacts of movement-based

programs adds to our understanding of how public libraries impact health and

wellness. Past research has investigated how public libraries impact health

through consumer health information services (e.g. Rubenstein, 2016), but has

not focused directly on the question of how public libraries impact health by

fostering active lifestyles. Being physically active throughout all stages of

life is one of the most important things people can do to be healthy (Kohl et

al., 2012). Better understanding the impacts of this emerging programming area

could potentially contribute to the development of tools to assess how public

libraries impact health and wellness, which could potentially be included in

the U.S.-based Project Outcome toolkit (Public Library Association,

2017), as well as in other assessment tools being developed elsewhere (Cole

& Ryan, 2016). Although more research is needed, the findings from this

exploratory study suggest that movement-based programs contribute both to

health and wellness as well as to community building. Furthermore, the fact that

so many libraries reported new users being brought to libraries because of

these types of programs suggests that these programs also contribute to

community engagement in libraries.

Limitations

The principal limitation of this work derives from

its exploratory nature. Rather than survey a randomized sample of all public

libraries in the U.S. and Canada, the researcher instead recruited a

self-selecting sample of public libraries, relying primarily on state and

provincial mediators to disseminate this survey to public librarians in their

regions. Future work should more rigorously test and refine these exploratory

results by using a randomized study design to enhance our knowledge and

understanding of how widespread these types of programs have become and what

impacts these types of programs have.

Despite this limitation, this study shows that many

public libraries throughout North America do offer a wide variety of

movement-based programs and most plan to continue offering these programs.

Based on these facts, more research is needed to understand why this

programming area has emerged, how it works, and what impacts it is having. In

addition to more quantitative data, we also need qualitative studies that look

in depth at the evolution and impacts of movement-based programs as they have

emerged and evolved in particular public libraries.

Conclusion

Past surveys of public libraries show that

movement-based programs have been offered in 20-30% of U.S. public libraries

(Bertot et al., 2015). Furthermore, case studies and journalistic reports show

that movement-based programs also occur elsewhere. Nonetheless, despite this

evidence little was known about the impacts these programs have had beyond the

particular cases discusses in past case studies and reports. This study added

to this literature by reporting data from a self-selecting sample of 1,157 U.S.

and Canadian public libraries that have offered movement-based programs. The

most consistently reported impact of movement-based programs in libraries is

that they bring new users into public libraries. Complicating assessment of the

impacts of these programs is the fact that a majority of respondents did no

assessment of their programs beyond counting the numbers of participants. The

need for more research on this topic is great; this article has sought to

provide needed evidence on this emerging programming area in order to support

future conversations and studies.

References

Anthony, C. (2016). Project Outcome: Looking back, looking forward. Public

Libraries Online, http://publiclibrariesonline.org/2016/01/project-outcome-looking-back-looking-forward/.

Bertot, J. C., Real, B., Lee, J., McDermott, A. J., & Jaeger, P. T. (2015). 2014 Digital Inclusion Survey: Survey Findings and Results.

University of Maryland, College Park: Information Policy & Access Center

(iPAC). http://digitalinclusion.umd.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/2014DigitalInclusionSurveyFinalRelease.pdf.

Cofell, J., Longair, B., & Weekes, L. (2015). Physical literacy in

the library or, how we ended up loaning out rubber chickens. PNLA Quarterly, 80(1), 34-36. https://arc.lib.montana.edu/ojs/index.php/pnla/article/view/295/218

Cole, B., & Ryan, P. (2016). Public libraries. In D. Koufogiannakis

& A. Brettle (Eds.), Being Evidence

Based in Library and Information Practice (pp. 105-120). London: Facet.

Dietzel-Glair, J. (2013). Books in

Motion: Connecting Preschoolers with Books through Art, Games, Movement, Music,

Playacting, and Props. Chicago: American Library Association.

EIFL. (2016). Keeping Fit in Romania: Pietrari Local Public Library

Helps the Community Get Back into Shape. http://www.eifl.net/eifl-in-action/creative-use-ict-innovation-award.

Engeszer, R. J., Olmstadt, W., Daley, J., Norfolk, M., Krekeler, K., Rogers,

M., Colditz, G., Anwuri, V.V., Morris, S., Voorhees, M., & McDonald, B.

(2016). Evolution of an academic–public library partnership. Journal of the

Medical Library Association: JMLA, 104(1),

62-66. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.104.1.010

Flaherty, M. G., & Miller, D. (2016). Rural public libraries as community change agents: Opportunities for

health promotion. Journal of

Education for Library and Information Science, 57(2), 143-150.

Gillaspy, M. L. (2005). Factors affecting the provision of consumer

health information in public libraries: The last five years. Library Trends,

53(3), 480-495. http://hdl.handle.net/2142/1738

Green, J. (2013). Thoughts on the power of arts with older adults. Creative

Aging Toolkit for Public Libraries, http://creativeagingtoolkit.org/power-of-the-arts-with-older-adults/.

Hamwaalwa, N., Teasdale, R. M., McGuire, R., & Shuumbili, T. (2016).

Promoting innovation in Namibian libraries through leadership training. Proceedings

of IFLA 2016, http://library.ifla.org/1509/1/189-hamwaalwa-en.pdf.

Hanson, T. (2012). Featured: Estherville’s Couch-to-5K. The

Association for Small and Rural Libraries Blog, http://arsl.info/esthervilles-couch-to-5k/.

Institute of Museum and Library Services. (2016). Data File

Documentation. Public Libraries Survey. Fiscal Year 2014. Washington, D.C.:

Institute of Museum and Library Services. https://www.imls.gov/sites/default/files/fy2014_pls_data_file_documentation.pdf.

Hill, J. (2017). Book-a-Bike: Increasing access to physical activity with

a library card. In M. Robison & L. Shedd (Eds.), Audio Recorders to Zucchini Seeds: Building a Library of Things (pp.

43-51). Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

Kaplan, A. (2014). Get Up and Move! Why Movement is Part of Early

Literacy Skills Development. University of Wisconsin Madison School of

Library and Information Studies. http://vanhise.lss.wisc.edu/slis/2014webinars.htm.

Kohl, H. W., Craig, C. L., Lambert, E. V., Inoue, S., Alkandari, J. R.,

Leetongin, G., Kahlmeier, S.,& Lancet Physical Activity Series Working

Group. (2012). The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public

health. The Lancet, 380(9838), 294-305. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60898-8

Lenstra, N. (2017). Let’s Move! Fitness programming in public libraries. Public Library Quarterly, 36(4), 1-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2017.1316150.

Library Journal. (2014). Public

Library Maker & Non-book Related Programming Report. Unpublished

manuscript, American Library Association.

Maddigan, B. C. & Bloos, S. C. (2013). Community library programs

that work: Building Youth and Family Literacy. Santa Barbara: Libraries

Unlimited.

Morgan, A. U., Dupuis, R., Whiteman, E. D., D’Alonzo, B., &

Cannuscio, C. C. (2017). “Our doors are open to everybody”: Public libraries as

common ground for public health. Journal

of Urban Health, 94(1), 1-3. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11524-016-0118-x

National Library Board of Singapore. (2017). Exercise Programs. https://www.nlb.gov.sg/golibrary2/c/30307529/result/term/exercise.

Nicholson, S. (2009). Go back to start: Gathering baseline data about

gaming in libraries. Library Review, 58(3), 203-214. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242530910942054

Oehlke, V. (2016). PLA President’s Report, ALA 2016 Annual Conference.

Chicago: Public Library Association. http://www.ala.org/pla/sites/ala.org.pla/files/content/about/board/vailey_oehlke_presidents_report.pdf.

Peterson, J. (2017). Growing library garden programs. WebJunction.

http://www.webjunction.org/news/webjunction/growing-library-garden-programs.html.

Prato, S. (2014). Music and movement at the library. Association for

Library Service to Children Blog, http://www.alsc.ala.org/blog/2014/11/music-and-movement-at-the-library/.

Public Library Association. (2017). Project

Outcome: Measuring the True Impact of Public Libraries. https://www.projectoutcome.org/.

Ryan, P. (2012). EBLIP and public libraries. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 7(1), 5-6. https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/eblip/index.php/EBLIP/article/view/16557/13672

Quatrella, L., & Blosveren, B. (1994). Sweat and self-esteem: A

public library supports young women. Wilson

Library Bulletin, 68(7), 34–36

Richmond, A. (2012). Running and reading at Rye public library. Granite

State Libraries, 48(3), 12. http://fliphtml5.com/gjox/riia/basic.

Rubenstein, E. L. (2016). Breaking health barriers: How can public

libraries contribute? Public Library Quarterly, 35(4), 331-337. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616846.2016.1245006

St. Louis County Library. (2014). Bean Stalk Ballet, 5.1.14. Flickr.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/slclevents/sets/72157644064466020/.

Vincent, J. (2014). An overlooked resource? Public libraries’ work with

older people–an introduction. Working

with Older People, 18(4):

214–222.

Weekes, L. & Longair, B. (2016). Physical literacy in the

library—Lethbridge Public Library, Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada. International

Information and Library Review, 48(2),

152-154.

Woodson, D. E., Timm, D. F., & Jones, D. (2011). Teaching kids about

healthy lifestyles through stories and games: Partnering with public libraries

to reach local children. Journal of

Hospital Librarianship, 11(1),

59-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/15323269.2011.538619

Zhu, J. (2017). Perfect Combination of Reading and Sports. Proceedings of IFLA 2017, http://library.ifla.org/id/eprint/1869.

Appendix

A

Let’s

Move in Libraries Survey

Q1. These questions ask for some background

information on your library. What is the zip code, or postal code, of your

library's physical location?

Q2. If you would like to provide it, what is the

name of your library?

Q3. Survey Part 1. This survey first asks about

programs or services your library has offered in the past or currently offers

in the present. At the end of the survey you will be given the opportunity

to discuss programs or services your library is planning, but has not yet

offered to the public. Has your library ever offered any programs or

services that include (select all that apply)? [Note: Responses to Q3

were carried forward for the remainder of the survey]

Movement-based

programs for early literacy (e.g. Music and Movement)

Yoga

Tai

Chi

Zumba

Dancing

Walking,

hiking, bicycling, or running

StoryWalks

Gardening

Fitness

challenges (e.g. pedometer challenge, biggest loser programs, Couch to 5K)

Fitness

equipment that can be checked out, including passes for gyms or aquatic centers

Other

programs or services

No

programs or services involving movement

Q3.B. [If “other programs or services”

selected than this question appears.] What other movement-based

programs or services has your library offered?

Q4. Survey Part 2. You are now invited to

participate in the second part of this survey. This part of the survey consists

of 16 questions that ask about the administration of the programs and services

your library offers, or has offered in the past. It should take about 10

minutes to complete. Would you like to participate in the second part of this

survey?

[If respondents select “no” they skip to Q26.]

Q5. These questions ask about the timing of programs

and services your library offers, or has offered. [Carried forward

programs] first offered by your library:

After

Jan. 1, 2016

Before

Jan. 1, 2016

Don’t

know

Q6. Since your library started offering these

programs and services, how regularly, on average, has your library offered

them to the public? [Carried forward programs] offered:

Only

once

More

frequently than once a month

Once

a month

Less

frequently than once a month

Not

applicable

Don’t

know

Q7. On which days and times has your library offered

the following [Carried forward programs] (select all that apply)

Weekday

mornings

Weekday

afternoons

Weekday

evenings

Weekend

mornings

Weekend

afternoons

Weekend

evenings

Not

applicable

Don’t

know

Q8. These questions ask about who these

programs/services are for, and also who participates in them. For which

audiences are these [Carried forward programs] targeted? (select

all that apply)

Youth,

birth-5

School-aged

youth

Tweens

and teens

Adults

Senior

Citizens

Families

All

ages

Don’t

know

Q9. How would you characterize participation levels

in these programs? [Carried forward programs] participation:

Exceeded

expectations

Met

expectations

Fell

below expectations

Don’t

know

Q10. This question asks about the reasons your

library offers these programs. For each of the programs your library

offers, please indicate which of the following are reasons for the program. If

multiple reasons, please select multiple responses.

Lifelong

learning

Literacy

Health

and/or wellness

Community

engagement

Other

Don’t

know

Q11. Please discuss other reasons, if any, your

library offers these programs.

Q12. These questions ask about how programs and

services in your library relate to other spaces and programs in your service

area. Please answer to the best of your ability. Where are your library's

programs and services physically located?

Within

a community room or auditorium located within the library

Within

another space in the library

Outside

the library

Not

applicable

Don’t

know

Q13. If you have other information about the

location of these programs and services, please record it here.

Q14. Who leads or directs these programs and

services? (select all that apply). [Carried forward programs] led

by:

Librarians

or library paraprofessionals

Paid

contractors

Partner

institutions or groups

Individual

volunteers

Other

Don’t

know

Q15. If your library developed these programs and

services with partners (e.g. parks departments, public health departments,

YMCAs, etc.), please specify who these partners are here.

Q16. These questions ask about the management and

administration of these programs and services. Are these programs/services

under the supervision of a particular division of your library? If so, which

ones. (Select all that apply). [Carried forward programs]

supervised by:

The

library as a whole

Adult

services

Teen

services

Youth

services

Programming,

outreach, or lifelong learning staff

Other

Don’t

know

Q17. If needed, please discuss here how these

programs and services fit within your organizational hierarchy.

Q18. For the following programs and services, are

any of the following ever required? (select all that apply). [Carried

forward programs] sometimes or always require participants:

Register

in advance

Sign

a waiver of liability

Pay

a fee

Do

something else

No

requirements for participation

Don’t

know

Q19. How are these programs and services funded?

(select all that apply). [Carried forward programs] funded by:

Regular

library budget

Programming

budget

Friends

of the Library

Donations

Grants

Other

Don’t

know

Q20. How have programs been marketed? (select all

that apply). [Carried forward programs] marketed through:

Print

flyers

Newspaper

advertisements or articles

Website

Online

calendar

Social

media

Word

of mouth

Other

Don’t

know

Q21. How have the programs and services been

assessed (select all that apply)? ). [Carried forward programs]

assessed through:

Head

counts of participants

Surveys

of participants

Interviews

with participants

No

assessment

Other

Don’t

know

Q22. What other administrative issues or challenges

has your library had to address in organizing these programs and services?

Q23. These questions ask about the impacts of these

programs and services. Has the media reported on the fact that your

library is offering [Carried forward programs]?

Yes

No

Don’t

know

Q24. This question asks about how these programs and

services engage your community. Have these [Carried forward programs]

brought new users into your library?

Yes

No

Don’t

know

Q25. Based on feedback and evidence you have collected,

have these [Carried forward programs] contributed to any of the

following (select all that apply)?

Health

and/or wellness

Literacy

Community

building

Outreach

Other

Don’t

know

Q25.b. If "other impacts" selected, please

discuss them here.

Q26. In the future, does your library plan to

provide any programs or services that include (select all that apply)?

Movement-based

programs for early literacy (e.g. Music and Movement)

Yoga

Tai

Chi

Zumba

Dancing

Walking,

hiking, bicycling, or running

StoryWalks

Gardening

Fitness

challenges (e.g. pedometer challenge, biggest loser programs, Couch to 5K)

Fitness

equipment that can be checked out, including passes for gyms or aquatic centers

Other

programs or services

No

programs or services involving movement

Q26.b. [If “other programs or services”

selected than this question appears.] What other movement-based

programs or services does your library plan to offer in the future?

Q27. Thank you for taking the time to fill out this

survey. If you have additional comments about these programs or services, or

about this survey, please record them here.

Q28. If you would like to be entered into the raffle

for one of the ten (10) $50 gift certificates from Amazon.com, please record

your email address here.

![]() 2017 Lenstra. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Lenstra. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/),

which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.