Research Article

Connecting Music and Place: Exploring Library

Collection Data Using Geo-visualizations

Carolyn Doi

Music & Education

Librarian

University Library

University of Saskatchewan

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan,

Canada

Email: carolyn.doi@usask.ca

Received: 23 Jan. 2017 Accepted:

26 Mar. 2017

2017 Doi. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Doi. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

Abstract

Objectives – This project had two stated objectives: 1)

to compare the location and concentration of Saskatchewan-based large

ensembles (bands, orchestras, choirs) within the province, with the intention

to draw conclusions about the history of community-based musical activity

within the province; and 2) to enable location-based browsing of

Saskatchewan music materials through an interactive search interface.

Methods – Data was harvested from MARC metadata found in

the library catalogue for a special collection of Saskatchewan music at the

University of Saskatchewan. Microsoft Excel and OpenRefine were used to screen,

clean, and enhance the dataset. Data was imported into ArcGIS software, where

it was plotted using a geo-visualization showing location and concentrations of

musical activity by large ensembles within the province. The geo-visualization

also allows users to filter results based on the ensemble type (band,

orchestra, or choir).

Results – The geo-visualization shows that albums from

large community ensembles appear across the province, in cities and towns of

all sizes. The ensembles are concentrated in the southern portion of the

province and there is a correlation between population density and ensemble

location. Choral ensembles are more prevalent than bands and orchestras, and

appear more widely across the province, whereas bands and orchestras are

concentrated around larger centres.

Conclusions – Library catalogue data contains unique information

for research based on special collections, though additional cleaning is

needed. Using geospatial visualizations to navigate collections allows for more

intuitive searching by location, and allow users to compare facets. While not

appropriate for all kinds of searching, maps are useful for browsing and for

location-based searches. Information is displayed in a visual way that allows

users to explore and connect with other platforms for more information.

Introduction

Local music collections

are a type of library collection composed of music or musical materials that

are representative of an identified place or location. Previous approaches for

searching library or archival holdings of local

music in online environments has primarily involved use of public access

catalogues, finding aids, or digital asset management systems. These approaches

to searching are useful for text-based queries, but may hinder understanding of

the connection to place, which is the unique and defining aspect of local

music. This paper illustrates the potential for analysis of local music

materials using a geo-visualization tool based on a case study of large

ensemble sound recordings from a local music collection at the University of

Saskatchewan. Results are presented and analyzed using a map developed on the

ArcGIS platform. This approach uses identification by ensemble location and

categorization by ensemble type, plotted using clusters and points on a

topographic map.

The dataset used for

this research was built from library catalogue records of sound recordings in

the Saskatchewan Music Collection (SMC), a historical local music collection at

the University Library, University of Saskatchewan. The collection aims to

preserve the musical heritage of the province through collection of local music

materials, containing representative items from the early 1900s to the current

day. Items meet collection criteria when they are considered local by

demonstrating a connection to an artist, composer, music label, or topic

relating to places within the Canadian province of Saskatchewan.

This is a growing

collection that, as of January 2017, contains 3202 items, the majority (90.9%)

of which are sound recordings. These items are physically held in the Education

& Music Library at the University of Saskatchewan, and are fully catalogued

and findable in the Library catalogue under the series title “Saskatchewan

Music Collection.” Approximately a third of the SMC has been digitized and is

available online through Sask History Online (SHO), an initiative that aims to

bring together digital collections from galleries, archives, museums, and

libraries within the province (http://saskhistoryonline.ca/). SHO is built on the Islandora platform, an

open-source software framework for digital asset management (https://islandora.ca/).

Project Background

An overview of the

origins of this project will help to contextualize the analysis presented in

this paper. The music represented in the

Saskatchewan Music Collection is not limited by format or genre, aiming to

preserve and make available music pertaining to all aspects of the province’s

history. One of the defining features of this musical history is a prevalence

of music from community-based large ensembles, which have often been

established by and connected to community organizations such as schools,

service clubs, churches, or arts organizations.

During an exhibit of SMC

materials at the University Library in early 2015, it was the albums of

community bands, orchestras, and choirs connected with rural Saskatchewan towns

and cities that especially engaged visitors. The album covers provided a unique

gateway into stories and memories connected with the musical activities of

these places. This experience prompted me to consider how the digitized albums

from the SMC might be presented in a similar way, where one might have the

opportunity to learn more about the connection between the music and geography

of the province.

In the spring of 2016,

the Engineering and GIS Librarian (Kristin Lee) and I (Carolyn Doi) launched a

project to develop a geo-visualization using the local music collection data.

The goals of this project were to create a dataset from the SMC catalogue data,

and to present this dataset online for public use in a geo-visualization tool.

I managed the musicological and music collection management aspects of the

project, while Lee oversaw the aspects related to data management and map

development. Staff in the Education & Music Library, Library Systems &

IT, and the collections unit also offered additional support for the data

collection, cleaning, and implementation of the map.

This paper shows the

process for collecting the data, cleaning the data, and building the

geo-visualization. This is followed by a presentation of findings based on the

data analysis, conducted in late 2016.

Literature Review

History of Music in

Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan is a

prairie province located at the geographic centre of Canada. Settled in 1774

and then created in 1905, the musical life within the province has been defined

in many ways by geography, climate, settlement, and industrial history. Its

musical origins are tied to a diversity of contributors including: “military

and police bands, church choirs, immigrant teachers, enthusiastic residents,

and . . . many travelling groups of instrumentalists and singers who came by

rail across the continent from the earliest days of settlement” (Swales,

2006b).

Literature on the

history of artistic development of the province is sparse, often found

primarily in encyclopedias, general histories of Canadian music, or in more

anecdotal sources such as newspapers and reports. An early account of this

history by Robert Solem, as summarized by Lewis, recounts the quick development

in the early years of the province as especially vibrant:

. . . a period of rapid growth accompanied by a spirit of musical

optimism. By 1912 the city of Saskatoon, for example, could boast of four good

bands, two good orchestras, a Conservatory of Music, and a Philharmonic

Society. This society was established by a large and energetic group of music

teachers (1973, p. 6).

The history of bands,

orchestras, and choirs in the province has been documented intermittently,

primarily through narrative summaries. Despite this, there is evidence that the

province was flourishing with artistic activity.

Orchestras

Although fewer in number

than other types of ensembles, Saskatchewan has maintained two notable

orchestras since the early 1900s. The Regina Symphony Orchestra (RSO) was

founded in 1908 and is known as one of Canada's oldest symphony orchestras.

Originally known as the Regina Orchestral Society, its first concert was given

on December 3, 1908, under the direction of its founder, L. Frank Laubach

(Wall, 2006). Meanwhile, in 1927, 40 amateur members came together to form an

early iteration of the Saskatoon Symphony Orchestra (SSO). The only symphony in

the northern part of the province, the SSO is one of the only ensembles in the

region that performs major symphonic repertoire on a regular basis (Conway,

2006). The presence of these ensembles is significant since they act to

encourage the overall health of the musical community. As “magnets for

orchestral performers,” who by extension “enrich the musical life of the

community as soloists, as players in . . . other musical groups . . . and as

music teachers” (Conway, 2012a).

Bands

Wasiak’s paper “School

Bands in Saskatchewan, Canada: A History”

outlines the history of school band development in the province, including

an overview of curricular development, repertoire, historical impacts,

challenges, and teaching methods. He states that the implementation of band

programs in the schools occurred “comparatively late” in the province and it

was not until the 1950s that bands “gained a foothold in the province's

schools” (2000, p. 113). Development was influenced both by “British bands,

[which] were the prototypes for the first military, civilian, and (later)

community bands in the province” and by “widespread and profound” American

influences, which included teaching methods, repertoire, and expertise (p.

125).

Choirs and Choir Music

The development of the

Saskatchewan Arts Board, choral societies, and arts festivals were influential

in the development and support for the many community choirs, which were

prominent in local churches, schools, and communities (Swales, 2006b). Church,

school, and community choirs were at the core of the Saskatchewan music

festivals in the early 1900s and were known for their large numbers of

participants. “Many church choirs exceeded fifty members, and in the 1950s the

Bishop’s School for Choristers in the Diocese of Qu’Appelle had over 100 boys

annually each summer” (Swales, 2006a). In the paper “What about Choral Art

Music from the Prairies?,” Morgan

identifies five features of choral music from the prairies including: 1) the

Christian church, 2) prairie landscapes, 3) secondary and post-secondary

education, 4) the arrival of new immigrants, and 5) Aboriginal culture (n.d, p.

3). These themes, Morgan states, have had a profound influence on the history

of choral music (and by extension, other musical genres) from the prairies,

which is made up of a “rich artistic community that is well endowed with

musicians who create and develop choral art” (p. 19).

Geo-visualizations and

Digital Libraries

Within the realm of

computer science, there has been extensive literature on the topic of

geo-visualizations as they relate to digital libraries. One of the earliest and

most widely cited pieces of literature introducing the concept of data

visualization comes from Ahlberg and Shneiderman’s chapter titled “Visual

Information Seeking: Tight Coupling of Dynamic Query Filters with Starfield

Displays” from 1993, which discusses the new concepts of

“visual information seeking” applications and methods. The authors pose several

principles unique to visual search such as: “dynamic query filters [that] are

rapidly adjusted with sliders, buttons, etc.,” “starfield display . . . result

sets [that] are continuously available and support viewing of hundreds or

thousands of items,” and “tight coupling . . . query components [that] are

interrelated in ways that preserve display invariants and support progressive

refinement” (pp. 313-14). These principles set the foundation for many of the

visualization case studies being implemented today.

The literature on using

geo-visualizations to understand music collections has focused on personal

libraries (Leitich & Topf, 2007; Torrens, Hertzog, & Arcos, 2004) or

commercial applications (Pampalk, Rauber, & Merkl, 2002). The literature on

data visualizations for use in cultural heritage institutions has been less

saturated, though it is growing in recent years. Much of this research comes in

the form of case studies that focus on how visualizations can: assist

librarians in collection assessment activities (Kilb & Jansen, 2016;

Lowery, 2011), facilitate user understandings of print library collections

(Finch & Flenner, 2016), or improve access to digital collections (Deal,

2014; Shiri, 2008; Hoek & Mayr, 2014).

Music collections have

often presented challenges for libraries and archives when it comes to

information retrieval and organization. Typically, music collections are

represented with textual metadata and searchable using text queries, though

these are not ideal for browsing and serendipitous searching. As Deal identifies,

“browsing features, if they are offered, are often limited to a list of

metadata vocabulary terms or a search that displays the entire contents of a

collection, one page of 10-20 items at a time” (2014, p. 15). Additionally,

finding a way to manage non-textual information such as sound files or images

has posed challenges in the library systems environment. Speaking specifically

on the topic of ethnomusicological collections, Magas and Proutskova identify

both metadata and content management as challenging areas in the design of

music collection information retrieval, especially in relation to the audio

content (2013, p. 152).

Benefits are found when

visualizations are used to engage with spatial representations of data. It is

this interaction that has an “important role in sense-making activities

involving space. It allows users to restructure and modify a space's content

according to their perceptual and cognitive needs. For example, interaction

with the geographic space may support understanding of differences among

various types of locations and their associations with collections.” (Buchel

& Sedig, 2014, para. 3). While literature on geo-visualizations of music

collections in academic settings is limited, there are many examples of projects

within academic, commercial, and public domains that serve as examples of the

potential for such work. Notable examples include maps representing locations

of music library collections (González Ribot, 2015; Ward, 2015), maps

documenting musical events in time such as the Travelling through Time with Sounds project (Europeana, n.d.), and

maps created to link users with items from a music collection, such as the Smithsonian Folkways Holiday Music Map

(2013).

Aims

This project had two

identified aims:

1)

to understand the

number, location, and concentration of community-based large ensembles in

Saskatchewan and

2)

to enable location-based

searching and browsing of the Saskatchewan Music Collection.

These aims support a

longer-term goal to increase the visibility of the Saskatchewan Music

Collection and to increase visibility of Saskatchewan music by making it more

accessible to the public and scholarly community.

Methods

Data Collection and Screening

MARC catalogue records

from the Saskatchewan Music Collection were used as the basis for analysis in

this project. The catalogue data was exported in a .csv file format and

initially contained records for all items from the SMC (3202 items). Screening

criteria were established to narrow the dataset. Items were included if they

met the following screening conditions:

1)

Sound recordings in any

format.

2)

Recordings by large

ensembles that were in an identifiable place (city or town) in Saskatchewan.

Large ensembles were defined as musical groups that self-identified as choirs

(including children’s choirs, church choirs, and community choirs), bands

(including concert bands, wind bands, and pipe bands), or orchestras (symphony

orchestras, string orchestras, and fiddle orchestras).

Items were excluded if

they met the following criteria:

1)

Sound recordings

containing reductions of choir, band, or orchestra music but not performed by a

large grouping of musicians (e.g., a quartet playing string orchestra parts).

2)

Ensembles that were not

associated with a place within the province. For example, a group might be

based in another province, but have recorded the music in Saskatchewan.

3)

Items that had not been

digitized and uploaded to the Islandora digital asset repository system at the

University of Saskatchewan.

The screening was

conducted by applying filters using the “find” feature in Microsoft Excel for

bands, orchestras, choirs, and related subject terms. No date filters were

applied, as all eras were of interest. After the screening process, 119 results

remained.

Data Cleaning

The dataset was cleaned

first using Microsoft Excel and then using OpenRefine software. When the data

was first received, each record contained 113 fields. The empty fields were removed

(many were empty MARC fields) as were any fields determined to be irrelevant to

this project (e.g., the MARC field 90 containing the library call number). MARC

field numbers were then translated to natural language headings. At this point

in the process, a field containing the ensemble location was added. In some

cases, this information was found in the dataset, album cover, or liner notes,

but when the information was not clearly indicated, additional research was

done to identify the location of the ensemble.

In the second phase of

cleaning, the dataset was imported into OpenRefine, an open source application

that can be used for data cleanup processes (http://openrefine.org/). Most of this stage of cleaning involved

adding new fields and standardizing the language within the records. Standard

OpenRefine commands such as “find and replace,” “slice,” “chomp,” and “trim”

were employed to standardize language and organize data. Information on how to

apply these commands in OpenRefine was aided by use of the OpenRefine GitHub

wiki page (Wicentowski, 2015). Records were enhanced by adding new fields and a

unique identifier for each record. The ensemble categories (choir, band, or

orchestra) were added, and in cases where an album included more than one type

of ensemble, multiple categories were applied. Three types of URLs were added

to each record: a link to the item record in the University Library catalogue,

a link to the digital album in the Islandora repository, and a link to the

location of the cover image of the album located on the Islandora server.

Existing information in

the records also needed to be standardized, because of variations in the

catalogue language practices. The information in the 300 field (description)

was used to add a new format field in the record added to indicate the type of

sound recording (formats included 33⅓ rpm, 45 rpm, 78 rpm, and compact disc).

The information found in the 260 field (publication) was extracted to identify

a place of publication. Place names needed to be standardized, as variations in

cataloguing practices have resulted in the same types of information being

represented in multiple ways. For example, the name “Saskatchewan” appears in a

variety of ways, including “SK,” “Sask,” and “Saskatchewan.” Using OpenRefine

facet filters and reconciling category function was useful in grouping

variations of the same word for editing. Using the “cluster” feature allows the

user to group information that might be related and the “merge” option provides

an easy way to reconcile some of the values.

Table 1

Comparison of

Terminology Allowed in RDA 3.4.1.3 Extent (“300 $a,” Yale University)

|

RDA 3.3.1.3

|

Alternative: Common

Usage

|

AACR2

|

|

audio disc

|

CD or compact disc

|

sound disc

|

|

audiocassette

|

cassette or cassette

tape

|

sound cassette

|

|

audio cartridge

|

MiniDisc

|

sound disc cartridge

|

Subject headings found

in the 650 field were cleaned using the OpenRefine “slice” function to remove

unnecessary characters, words, and duplication. For example, “|aChoruses with

band|zSaskatchewan|aBand music|zSaskatchewan” was updated to “Choruses with

band; Band music” in the final dataset. In this case, the word “Saskatchewan”

was removed because it is assumed all items in the dataset are from

Saskatchewan. Semi-colons were added instead of pipes, in order to clean the

appearance of this information in the public-facing map.

Based on the location of

the ensemble, latitude and longitude fields were added to the dataset. This was

done using the Google Geocoding API, a service that converts addresses into

geographic coordinates that can then be used to place markers on a map (Google

Developers, 2017). Instructions for how to translate addresses to latitude and

longitude data were located in the OpenRefine GitHub wiki (Moscovitz, 2015).

The finalized dataset was published through the University of Alberta DataVerse

project (Doi & Lee, 2017b).

Challenges

Using library catalogue

metadata to build the dataset had both advantages and disadvantages. Even

though using tools such as OpenRefine simplified the process, it still took

considerable time and several members of staff to clean and finalize the

dataset. Since the MARC catalogue records had been created by a variety of

means, including outsourced copy cataloguing and internal original cataloguing,

the initial dataset was inconsistent. This was particularly apparent in the way

that musical formats are described in the MARC records. This information is

usually found in the 300 field for physical description, though standards for

the type of information to include in this field varies from AACR2

(Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, 2nd edition) to RDA (Resource Description

and Access). These may include extent, duration, sound characteristics,

dimensions, content type, media type, and carrier type (Yale University

Library, n.d.a). This information is not always included consistently, and when

it is, variant forms of spelling or terminology may be used. RDA 3.4.1.3 allows

use of either an authorized term from the list at 3.3.1.3, or, as an

alternative, a term in common usage (see Table 1).

The original MARC record

includes a place of publication, but this information was not always

consistently formatted. In some cases, this is because publication information

on sound recordings has not been regulated in the same way as monographs; in

other cases this is because some sound recordings were produced independently

by the artist, resulting in inconsistent formatting on the albums.

While these challenges

with the catalogue data slowed our processes, it was by reducing the size of

the dataset that the project remained manageable. The same work might be more

challenging with a larger or more diverse set of records.

Data Visualization

The dataset was exported

into .csv file format and imported into ArcGIS, a mapping and analytics

platform that provides “contextual tools for mapping and spatial reasoning . .

. to explore data and share location-based insights” (ESRI, n.d.). ArcGIS was

chosen in part because there is internal support for the platform at the

University of Saskatchewan, and more importantly because it provided a stable

platform on which to present the data to meet the research aims for this

project. For this project, we implemented two instances of ArcGIS: a privately

managed project where data can be imported and visualization aspects can be

managed, and a public facing map developed using the Web App Building provided

by ArcGIS (Doi & Lee, 2017b).

The records in the

dataset are plotted on the map per ensemble location. This is defined as the

place(s) where the ensemble was or is primarily located or with which it is

associated. In some instances, an ensemble is associated with more than one

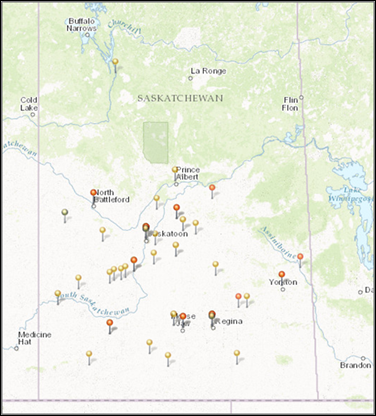

location and appears more than once on the map. The map contains several

layers, which can be switched on or off by the user. All ensembles can be

displayed on the map using the “all ensembles – location points” layer, which

pinpoints the locations (see Figure 1).

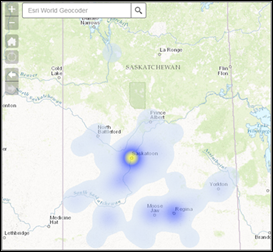

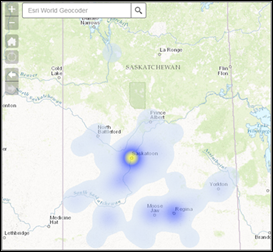

Using the “all ensembles

– location clusters” layer displays the same information using a heat map,

where concentration of ensembles is defined by variations in the colour (see

Figure 2).

Figure

2

All ensembles – location

clusters layer enabled.

Information about the

ensembles can also be displayed by ensemble type, by switching the orchestra,

choir, or band layers, which displays the representation of each using coloured

pins (see Figure 3).

More detailed

information about each album can be displayed by clicking on specific locations

to reveal an information box or by opening an attribute table below the map.

The displayed fields include album title, ensemble name, ensemble location,

format, publication location, publication date, latitude and longitude

coordinates, a URL linking to the catalogue record, a URL linking to the

digitized album, and an image of the front cover. If more than one ensemble

exists at the same coordinate, this is indicated in the upper portion of the

information box. A search box is present in the mapping interface, which allows

users to search by location (e.g., Saskatoon, Prince Albert, or others) or

place (e.g., University of Saskatchewan, Kinsmen Hall, or others).

Figure

3

Choirs

layer enabled and information box.

Results

Concentrations of

Musical Activity

Comparison of data from

the ArcGIS World Population Estimate map and the SMC heat map reveals a direct

correlation between the number of albums produced and the size of a town or

city (ESRI, 2016). The area measurement tool was used to determine the reach

and concentration of the plotted musical recordings, showing that almost all

the recordings are in the southern half of the province. This accounts for approximately

202,063 square kilometers (34.35%) of the total 588,239.21 square kilometers

occupied by the province (Statistics Canada, 2015).

These findings also show

clusters around larger centres in the province, such as Saskatoon and Regina,

demonstrating a connection between city size and number of ensembles (see Table

2).

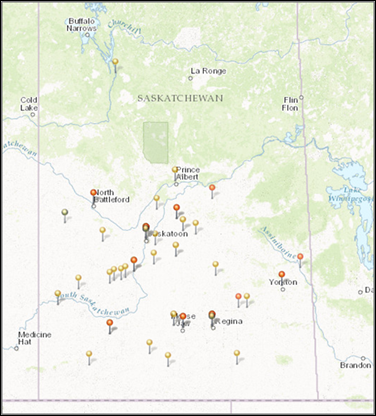

Enabling layers within

the ArcGIS map shows the location of ensembles filtered by ensemble type. These

findings show that choirs make up the largest percentage of ensemble recordings

within the province, representing 77.31% of the total albums. Bands make up the

second largest percentage, representing 21.85%, and orchestras make up the

lowest, representing 0.07%. In some of these cases, an album might contain

music from more than one ensemble type, explaining the higher total number of

ensemble representations overall than the total number of albums included in

the dataset. When comparing the number of ensemble types to the location data,

findings show that more concentrated centres such as Regina and Saskatoon are

likely to contain all three ensemble types, while the choirs are more likely to

appear in rural locations (see Figure 4).

Table

2

Saskatchewan

Populations Compared with Number of Albums per Location

|

City name

|

City size (2011 census) (Statistics Canada,

“Saskatchewan Population Report”)

|

Number of albums per location

|

|

Saskatoon

|

222,189

|

41

|

|

Regina

|

193,100

|

18

|

|

Moose Jaw

|

33,274

|

5

|

|

Outlook

|

2,204

|

9

|

|

Swift Current

|

15,503

|

5

|

Figure

4

Concentration

of large ensembles by genre: orchestras, bands, and choirs.

When ensemble types are

compared alongside ensemble names using the table feature in ArcGIS, we can see

trends between ensemble location and the responsible community organization.

While orchestras are more likely to be associated with a city or university

(e.g., University of Saskatchewan Wind Orchestra and Saskatoon Junior Symphony

Orchestra), bands were more often associated with a school, community

organization, or military affiliate (e.g., Aden Bowman Collegiate Band, Melfort

Kinsmen Band, and Royal Canadian Air Force Wing Auxiliary Band,). Finally,

choirs were associated with a wider variety of organizations, including

schools, churches, universities, and community organizations (e.g., College

Park School Choirs and Rosthern Mennonite School Choir). The correlation

between population size, available services or community organizations, and

appearance of musical ensembles demonstrates a strong link between community

development and musical activity within the province.

Search Interface

Comparison of the three

interfaces where the SMC materials are now available for searching shows both

the benefits and drawbacks of searching within the mapping tool. Most notably,

the map allows for non-text based interaction with the collection, while text

searching remains more effective in either the catalogue or Islandora, except

in the case of searching by ensemble location (see Table 3).

Discussion

The findings of this

paper provide an as-yet unseen picture into the history of large ensembles

within Saskatchewan. While the existing narrative histories provide more

anecdotal perspectives on the musical activities, the visualization allows us

to see the big picture of development and its reach within the province.

Ties to Local History

The ability to track the

development of these three large ensemble groups within the province offers

insight into the similarities and differences between them. The establishment

of orchestras and bands typically relies on access to a variety of resources

including specific instruments, instruction, rehearsal space, and musicians,

which may have limited their overall numbers within the province. Bands and

orchestras may have needed community funding or financial support from

community organizations, which could have limited their numbers in comparison

to community choirs. Meanwhile, choirs were well established in the tradition

of church and school activities, and would have required fewer resources. As

churches and schools had a well- developed and pervasive network within both

urban and rural locations in the province, the development of community choirs

throughout the province was inevitable.

Musical activity within

the province was one indicator of development, which can be tied to many

others. Comparing the data of musical recordings to other data related to

community development or local history would provide a more complete picture of

the establishment of such community organizations and individuals within them.

Church records, local histories, or provincial archives might have additional

information on the formation and activity of musical ensembles.

While musical recordings

are just one type of evidence of musical development and activity, it is

nonetheless an important consideration of how music was produced, consumed and

distributed. Access to the album covers and liner notes often provides insight

into the activities of the ensembles, including rehearsal schedules, tour dates

and locations, individual members, and supporting members of the community. It

is these connections to community and place that make these materials such an

insightful window into local history.

Testing a Proof of

Concept

The geo-visualization

was initially developed as a proof of concept. This varied slightly from the

final design presented in this paper, as it used all the SMC items found in the

Islandora platform (over 1000) plotted per publication location. The data analysis

and visualization were realized using CARTO, a software that provides GIS and

web mapping tools for display in a web browser (https://carto.com/). The proof of concept was presented during the

Mountain Plains Chapter Meeting of the Music Library Association (Bogdan &

Doi, 2016), and feedback was gathered on the initial design.

Table 3

Comparison of Search

Interfaces: Library Catalogue, Islandora Digital Repository, and ArcGIS Map

|

Criteria

|

Catalogue

|

Islandora

|

ArcGIS Map

|

|

Text searching

|

Author,

title, subject, keyword, call number

|

Keyword

|

Location

|

|

Visual representation and searching

|

No

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

Portion of the collection

|

Complete

collection, 3000+ albums

|

Digitized

items, 1000 albums

|

Digitized

albums by large ensembles, 119 albums

|

|

Digital object included

|

No

|

Yes – images

and sound files

|

Yes – cover

image

|

|

Information in record

|

Standard MARC

fields:

001, 003,

005, 007, 008, 028, 040, 090, 245, 260, 300, 500, 505, 590, 650, 700, 710,

740, 830, 850, 902

|

Selected MODS

fields: artist, title, item type, table of contents, subjects, bib number, publisher,

place of publication, item description

|

Selected MARC

and added fields: album title, ensemble name, ensemble location, format,

publication location, publication date, decade, latitude, longitude, link to

catalogue record, link to Islandora record.

|

|

Link to other representations of the collection

|

No

|

No

|

Yes – links

to both catalogue and Islandora

|

The feedback revealed

that the geo-visualization had provided an effective overview of the collection

while also compelling users to explore selected albums. However, using the

place of publication as the primary location for the recordings presented a challenge

for users. While in some cases this geographic information was relevant to the

artist or recording (e.g., the album was published in the same city as where

the artist resided), in many others, the location of the music label was

tangentially related, and provided only supplementary information as to how

place relates to the artist or music. Based on this feedback, the dataset was

reconceived from June to August, 2016. These changes ultimately led to the

decision to further limit the inclusion criteria of the dataset, and to

incorporate information about the location of each ensemble.

Challenges

Using catalogue data as

a dataset was challenging because historical cataloguing practices have led to

inconsistencies due to changes in practice, variations in acceptable language,

and human error. This inconsistency was not unique to this collection, and

using library collection data will always require cleaning before use.

In this case, the music

materials themselves also presented additional challenges. Historical sound

recordings offer inconsistent information on basic elements of the publication,

and this inconsistency is amplified when many of the albums are

independently-published as in this case. Examples of this include missing

publication information, or variations in spellings of titles or artists. While

catalogue records are designed to accommodate for variations in spelling or

missing information, these variations are more challenging when trying to

achieve consistency in the dataset.

Limitations

As the process for

adding data to the map is not automated, it does not incorporate newly added

digital items from the SMC. As such, the map represents the collection at a

moment in time, and significant staff time would be needed to add new content.

The dataset used for

this project does not fully represent the recorded history of musical ensembles

in Saskatchewan. There are more known items located in the SMC that were

excluded because they have not yet been digitized. To achieve a more complete

representation of the musical recording history, workflows for adding new

content will need to be established.

Future Work

There are many

possibilities for expanding the work initiated in this research, including

expanding the dataset or adding additional types of information. There is also

potential to realize other aspects of the dataset within the visualization,

including the correlation between date and location.

While the data currently

included is drawn from the SMC, there are many other collections with materials

related to the history of music and large ensembles in Saskatchewan. Special

collections holdings at the University of Saskatchewan or items in the

Saskatchewan History Online project would provide a good starting place for

locating related materials. Such materials might extend the depth and breadth

of the story of this history and would also make good candidates for inclusion

in the project. Saskatchewan’s citizens have produced more than 2000 local

history books, which discuss the histories, lives, and activities of the town

or city, chronicling the “rise (and in some cases, the decline and demise) of

communities, families, churches, and businesses large and small across the

province.” (Massie, 2006). Linking the information in these sources might serve

to build more detailed narratives about the musical histories presented.

While the work to curate

the dataset for this project was done by staff at the university, there may be

opportunities to draw on local knowledge to enhance the data. Since there are

many aspects of local history that are missing from more traditional

information sources, implementing a system for collecting music histories from

the public might be a worthwhile option for developing the map further. By

implementing a crowdsourcing information gathering model, this project would

further serve to engage the public, to use the knowledge of the community, and

to add value to the data (Holley, 2010).

This project focusses on

mapping large ensemble items from the Saskatchewan Music Collection, but there

is potential to extend the mapping template beyond this collection. While not

all collections will be ideally represented in a geo-spatial environment, there

are certainly others to consider that might provide insight when seen through a

geographic lens.

Conclusions

This research presents a

picture of the history of musical life in the province of Saskatchewan and its

connection to historical social and economic development. Findings show that

there is a correlation between the population density of the province and the

prevalence of large ensembles within communities. It provides evidence that

these ensembles are often linked to community organizations and establishments

such as schools, churches, service organizations, and arts organizations. As

the province continues to develop we will certainly continue to see these

connections between music and place continue to grow and change.

Geo-spatial

visualizations have potential as a tool to draw new research conclusions about

the contents of library collections. Researchers who are considering using

catalogue data will find that it is a rich source of untapped data, which has

potential for exploring local histories.

Using an online mapping

tool such as ArcGIS provides an alternative way to explore special collections,

using parameters that are not accessible in interfaces such as the library

catalogue or digital content repositories. These tools demonstrate potential to

attract and engage a wide audience to explore library special collections and

audiovisual materials.

Acknowledgements

Aspects of this work

were originally presented at the 2016 Mountain Plains chapter meeting of the

Music Library Association in Greeley, CO and later at the Centre for Evidence

Based Library and Information Practice Symposium in Saskatoon, SK in 2016. My

thanks to K. Lee who collaborated with me on the implementation of this

project. Thank you to my colleagues at the University of Saskatchewan: C.

Sjoberg for her assistance with cleaning and enhancing the dataset and J.

McLean who offered helpful feedback on OpenRefine and cleaning library

catalogue data.

References

Ahlberg, C., & Shneiderman, B. (1993).

Visual information seeking: Tight coupling of dynamic query filters with

starfield displays. In S. K. Card, J. D. Mackinlay, & B. Shneiderman

(Eds.), Readings in information

visualization: Using vision to think. (pp. 244–250). San Francisco, CA:

Academic Press.

Bogdan, K. & Doi, C. (2016, May). Music in space and time: Using data

visualization to understand a local music collection. Paper presented at

the Mountain Plains chapter meeting of the Music Library Association in

Greeley, CO.

Buchel, O. & Sedig, K. (2011). Extending

map-based visualizations to support visual tasks: The role of ontological

properties. Knowledge Organization, 38(3),

204-229.

Buchel, O., & Sedig, K. (2014). Making sense

of document collections with map-based visualisations: The role of interaction

with representations. Information

Research, 19(3), 29-55. Retrieved

from http://www.informationr.net/ir/19-3/paper631.html#.WDxnufkrK00

Conway, K. (2006). Saskatoon Symphony Orchestra.

In The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan.

Retrieved from http://esask.uregina.ca/entry/saskatoon_symphony_orchestra.html

Crampton, J. W. (2002). Interactivity types in

geographic visualization. Cartography and

Geographic Information Science, 29(2),

85-98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1559/152304002782053314

Deal, L. (2014). Visualizing digital

collections. Technical Services Quarterly, 32(1), 14-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07317131.2015.972871

Department of Music. (2015). About ensembles. In

University of Saskatchewan, College of

Arts & Science. Retrieved from http://artsandscience.usask.ca/music/ensembles/

Doi, C. (2015). Local music collections:

Strategies for digital access, presentation, and preservation—A case study. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 21(2), 256-263. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2015.1022663

Doi, C. and Lee, K. (2017a). Choirs, bands, and orchestras of

Saskatchewan v1. Retrieved from https://spatialsk.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=de483307f29641a2b7682c3f09d517b8

Doi, C. and Lee, K. (2017b). Saskatchewan music

large ensembles. In University of Alberta

Libraries. http://dx.doi.org/10.7939/DVN/10974

ESRI. (2016). World population estimates.

Retrieved from: http://arcg.is/2jF68Ql

ESRI. (n.d.). About ArcGIS. Retrieved from http://www.esri.com/arcgis/about-arcgis

Europeana. (n.d.). Travelling through time with sounds. Retrieved from http://www.europeana.eu/portal/en/collections/music/travelling-through-time-with-sounds.html

Finch, J. L., & Flenner, A. R. (2016). Using

data visualization to examine an academic library collection. College and Research Libraries, 77(6), 765-778. http://dx.doi.org/10.5860/crl.77.6.765

González Ribot, M. J. (2015, June). Map of Spanish musical heritage.

Presented during the IAML/IMS annual meeting, Music

Research in the Digital Age, 21-26. June 2015, Juilliard School, New York, NY.

Retrieved from http://www.iaml.info/sites/default/files/pdf/map_of_spanish_musical_heritage_gonzalez_ribot_iaml_2015.pdf

Google Developers. (2017). Geocoding API: Getting started. Retrieved from https://developers.google.com/maps/documentation/geocoding/start?csw=1

Hilliges, O., Holzer, P., Klüber, R., and Butz,

A. (2006). AudioRadar: A metaphorical visualization for the navigation of large

music collections. In A. Butz, B. Fisher, A. Krüger, & P. Olivier (Eds). Smart Graphics, SG 2006. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 4073.

(pp. 82-92). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/11795018_8

Hoek, W. van, & Mayr, P. (2014). Assessing

visualization techniques for the search process in digital libraries. In S. A.

Keller, R. Schneider, & B. Volk (Eds.), Wissensorganisation

und-repräsentation mit digitalen Technologien. (pp. 63–85). Berlin: De

Gruyter Saur. Retrieved from http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-463733

Holley, R. (2010). Crowdsourcing: How and why

should libraries do it? D-Lib Magazine, 16(3/4). http://dx.doi.org/10.1045/march2010-holley

Islandora

(n.d.). About. Retrieved

from https://islandora.ca/about

Kilb, M., & Jansen,

M. (2016). Visualizing collections data: Why pie charts aren't always the

answer. Serials Review, 42(3),

192-200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00987913.2016.1207479

Krygier, J. B. (1994). Sound and geographic

visualization. In A. M. MacEachren and D. R. F. Taylor (Eds). Visualization in modern cartography. (pp.

149-166). New York, NY: Elsevier. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-042415-6.50015-6

Leitich, S., & Topf, M. (2007). Globe of music: Music library visualization

using Geosom. Retrieved from http://ismir2007.ismir.net/proceedings/ISMIR2007_p167_leitich.pdf

Lewis, M. (1973). Music in Saskatchewan. CAML Review, 2(1), 6-7. http://caml.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/caml/article/view/4148/3347

Lowery, R. (2011). A visualization tool for

atlas collection assessment. Journal of

Map & Geography Libraries, 7(2),

138-153. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15420353.2011.566837

Magas, M. & P. Proutskova. (2013). A

Location-Tracking Interface for Ethnomusicological Collections. Journal of New Music Research, 42(2), 151-160. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09298215.2013.821999

Massie, M. (2006). Local history. In The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Retrieved

from http://esask.uregina.ca/entry/local_history.html

Morgan, M. (n.d.). What about choral art music

from the Prairies?: An introduction to Canadian Prairie composers and their

compositions for SATB choir. Retrieved

from https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B1nJvB97aPfgLWtHemw1elI3M3M/view?usp=sharing

Moscovitz, M. (2015). OpenRefine: GeoCoding.

Retrieved from https://github.com/OpenRefine/OpenRefine/wiki/Geocoding

Pampalk, E., Rauber, A., & Merkl, D. (2002).

Content-based organization and visualization of music archives. In MULTIMEDIA ’02: Proceedings of the tenth ACM

international conference on Multimedia. (pp. 570-579). New York, NY: ACM

Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/641007.641121

Sask

History Online. (n.d.). About the

project. Retrieved from http://saskhistoryonline.ca/about

Saskatchewan Bureau of Statistics. (2012). Saskatchewan population report: 2011 Census

of Canada. Retrieved from http://www.stats.gov.sk.ca/stats/population/censuspop2011.pdf

Shiri, A. (2008). Metadata-enhanced visual

interfaces to digital libraries. Journal

of Information Science, 34(6), 763-775. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551507087711

Schumiatcher, M. & Luko, A. R. (2016).

Saskatchewan Arts Board. In The Canadian

encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/saskatchewan-arts-board-emc/

Smithsonian

Folkways holiday music map.

(2013). Retrieved from http://arcg.is/2jHgrke

Statistics Canada. (2015). Focus on geography series, 2011 census. Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-pr-eng.cfm?Lang=eng&GC=47

Swales, R. (2006a). Choirs. In The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan.

Retrieved from http://esask.uregina.ca/entry/choirs.html

Swales, R. (2006b). Music. In The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan.

Retrieved from http://esask.uregina.ca/entry/music.html

Symes, C. (2004). Setting the record straight: A material history of classical recording.

Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Torrens, M., Hertzog, P., and Arcos, J. L.

(2004, Oct.). Visualizing and exploring personal music libraries. Paper

presented at the 5th International Conference on Music Information Retrieval,

Barcelona, Spain, 10-14 October 2004. Retrieved from http://www.ee.columbia.edu/~dpwe/ismir2004/CRFILES/paper214.pdf

Wall, K. (2006). Regina Symphony Orchestra. In The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan.

Retrieved from http://esask.uregina.ca/entry/regina_symphony_orchestra.html

Ward, J. (2015). An Interactive Map of Musical Institutions in Belgium. Retrieved

from http://www.iaml.info/news/interactive-map-musical-institutions-belgium

Ward, N. (2009). Saskatchewan (province). In The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved

from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/saskatchewan/

Wasiak, E. B. (2000). School bands in

Saskatchewan, Canada: A history. Journal

of Historical Research in Music Education, 21(2), 112-131. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40215213

Wicentowski, J. (2015). GREL functions.

Retrieved from https://github.com/OpenRefine/OpenRefine/wiki/GREL-Functions

Yale University Library. (n.d.a). RDA

descriptive examples (1). Retrieved from http://web.library.yale.edu/cataloging/sound-recordings/music-popular/examples

Yale University Library. (n.d.b). 300 $a (Sound

recordings, RDA). Retrieved from http://web.library.yale.edu/cataloging/sound-recordings/non-music-checklist/300

![]() 2017 Doi. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.

2017 Doi. This is an Open Access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons‐Attribution‐Noncommercial‐Share Alike License 4.0

International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium,

provided the original work is properly attributed, not used for commercial

purposes, and, if transformed, the resulting work is redistributed under the

same or similar license to this one.